2011 June

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

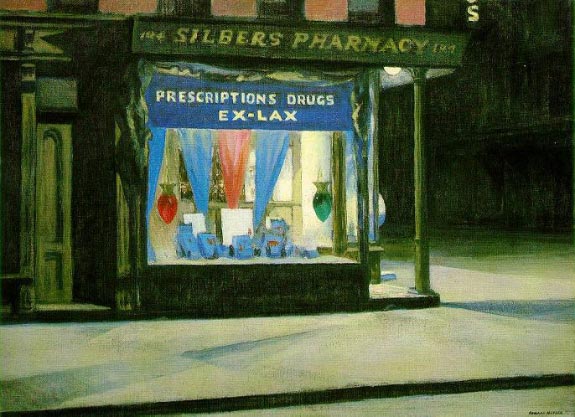

The American Drugstore

by Julián Marías

I REMEMBER MY ARRIVAL in Salt Lake City on a long shining train which had just crossed the endless plains of Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, and now had entered the land of the Mormons. When I got off the train and began to walk down the long avenue, now slick with ice, which stretches from the station to the Mormon Temple, I asked myself what I had lost in Utah, in this place where I didn’t even know the name of a single person. Undoubtedly the blame was this time – as in so many other cases – Jules Verne’s. Do you remember his Around the World in Eighty Days? Phineas Fogg, the phlegmatic gentleman, and his roguish servant Passepartout; in their company I came to know Utah and its Mormons for the first time, in my early youth. But let’s not deceive ourselves: youth somehow remains with us; I had a date with Salt Lake City from the age of ten, and now I was keeping it, walking slowly through the snow along a deserted street, toward the Mormon Temple, which glowed in the distance, and which can only be entered by the faithful.

This enormous temple, brightly lighted, seemed to orient and give meaning to the city. Very close by, the mountains, which surround the city and are visible on all sides, creating in its midst the image of a wild West. Frozen and almost deserted streets. And suddenly, the drugstore! There, in Salt Lake City, I finally understood its meaning. Always open, day and night, in any weather, brilliantly lit up like a beacon in the middle of the night, sheltering and hospitable like a port, full of things … like a drugstore, for in no other place are there so many things. Twenty-five-cent books on revolving wire stands; children’s records; magazines and newspaper; cigarettes, cameras, candies, luggage, electrical appliances, chairs, pens, toys, glasses, perfumes, stationery fishing tackle … anything you can think of. Since it has everything, there are even drugs and prescriptions in the American drugstore. And there is, strangely enough, a large counter, lined with plastic-covered stools, where one can order, at any hour of the day or night, and for a few cents, a couple of eggs, a cup of coffee, a milk shake, a hamburger, or what they call, with wonderful inventiveness, a cheeseburger. (more…)

The Architecture of Immaturity

Have you ever come across the French Ministry of Culture on the Rue Saint-Honoré? It’s a perfect example of the architecture of immaturity. The government ministry was formerly strewn across nineteen different sites throughout Paris. The decision was made to consolidate their offices in one place, and the suitably central location near the Palais Royal was chosen.

The main building on the site is a handsome building from the late nineteenth-century or at the latest 1900s, with a modern 1960s office building stuck behind it. The Ministère chose architect Francis Soler to “unify” the buildings into one. At first, this was meant to be done solely through an interior reorganisation, but Soler decided to add a strange grille to the façade. (more…)

Decline of the Herr Professor

The Herr professor has been caught up in a whirlwind of protest, eventually to emerge as a humble guest on a television talk show.

No Nobel prize compensates for this loss of prestige at the apex of a crumbling pyramid.

His desperate references to the false problem of “academic freedom” sound not only hollow, but like the exchanges between pagan Roman priests at magical ceremonies in whose effectiveness they no longer believed.

Modern Age, Spring 1999

Senator Eugene McCarthy: A Kirkian Anecdote

Russell Kirk, the great St Andrean and American man of letters, relates this anecdote in his article “Will American Caesars Arise?” (Modern Age, Summer 1989):

The most interestingly complex of all recent aspirants to the presidency, [Senator Eugene] McCarthy obdurately called himself a liberal during years when that appellation was sinking swiftly in popular favour – although he abjured all forms of liberalism earlier than Franklin Roosevelt’s. (During the past few years, as he now remarks, he has employed the word ‘‘liberal’’ as an adjective merely.) In his political theories, actually, McCarthy has been a conservative: He declared long ago that Edmund Burke was his political mentor, and no one has more warmly praised Tocqueville. He has read seriously and written intelligently. In the White House – per impossibile – he might have turned the most imaginatively conservative of Presidents.

Or perhaps not. Once upon a time I had an assistant who was a graphoanalyst, an expert on handwriting. Having examined a specimen of Senator McCarthy’s handwriting, my assistant pronounced him rebellious, a hard master, and desirous of power. A touch of Caesar even in Caesar’s adversary? However that may be, McCarthy’s only considerable assertion of power was his unseating of President Johnson by running a good second in the New Hampshire primary of 1968.

A congenital no-sayer, Eugene McCarthy never ran with the hounds. He was candid and witty always. He and I first met as debaters before a large audience, in Boston. After this exchange, sponsored by the Paulist Fathers, a reception was held for us. Up to Senator McCarthy came a zealous young Paulist, inquiring, “Senator McCarthy, don’t you think that Jack Kennedy is the finest president this nation ever has had?” (This occurred during the first year of the Kennedy administration.)

“No,” said McCarthy, unsmiling.

Although taken aback, the Paulist returned to the charge: “But surely you agree, Senator, that President Kennedy has given this nation a new hope, a new vigor, a sense of moving forward toward great things?”

“No,” said Eugene McCarthy.

The Paulist persisted: “But of course you’ll agree with me when I say, Senator, that the Kennedy family have brought to our life a culture, a refinement, a meaningfulness, that we have not known before.”

“No,” said Eugene McCarthy.

“But – but Senator McCarthy, surely Jack Kennedy is a very nice man personally?”

Eugene McCarthy turned his back upon the Paulist and slowly walked away. He knew how to say no, he was not ensnared by cliché and slogan, and he had a poet’s attachment to truth.

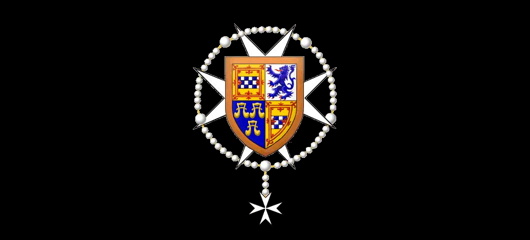

Fra Freddy, Rest In Peace

Yesterday, I was very saddened to hear of Fra Freddy’s death. Fra Freddy was a legendary character whom I was introduced to in my first year at St Andrews. He was invited to speak to the Catholic students most years on some subject or another — an introduction to prayer or a lenten meditation. I was quite pleased when he was so taken with a poster I designed to advertise one of his talks that on his way back to Edinburgh he nipped out of the car at the last minute and grabbed a large copy. Fra Freddy was an old-fashioned stick-in-the-mud with a good sense of humour, but he also had the capability to surprise with a kind word when you least expected it.

Fra Fredrik John Patrick Crichton-Stuart was born September 6, 1940 to Lord Rhidian Crichton-Stuart (son of the 4th Marquess of Bute) and his wife Selina van Wijk (daughter of the Ambassador of the Queen of the Netherlands to the French Republic). He was raised in Scotland and North Africa (where his father was British Delegate to the International Legislative Assembly of Tangier) and was educated first at Carlekemp in North Berwick and then at Ampleforth. He joined the Order of Malta in 1962, later being named the Delegate for Scotland & the Northern Marches. In 1993 he was appointed Chancellor of the resurrected Grand Priory of England. Fra Freddy became Grand Prior himself when his cousin, Fra Andrew Bertie, died in 2008 and was succeeded by the then-Grand Prior of England, Fra Matthew Festing.

Fra Freddy was a devoted follower and promoter of the traditional form of the Roman rite. He joined Una Voce Scotland in 1996 and became secretary in 2000. Two years later he was named councillor and senior vice-president of FIUV, the International Federation ‘Una Voce’, and briefly served as its president in 2005.

Over the past year or so Fra Freddy had been varying ill but seemed to recover. I am told he was found dead yesterday morning, still clasping his breviary. He was well-known in Edinburgh and beyond, and he will be missed by his many friends as well as those who worked and volunteered with him or interacted with him in his charitable activities.

FREDERICK JOHN PATRICK CRICHTON-STUART

Grand Prior of England

of the

Sovereign Military & Hospitaller Order of St John

of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta

6 September 1940 – 14 June 2011

Eternal rest grant unto him, O Lord,

and let perpetual light shine upon him.

May he rest in peace.

Amen.

Cooking with Sir Laurens van der Post

East and West Meet at the Cape

The Cape Malays came up with dishes that are all so a part of the South African way of life that they have become almost sacramental substances. Among them are bobotie, sosaties, and bredie. Bobotie, a kind of minced pie, is to South African what moussaka is to the Greeks. Sosaties, or skewered and grilled meats are what shashlyk are to the people of the Caucasus and shish kabob to the Turks. The stew called bredie is what goulash is to Hungarians.

A basic bobotie begins with minced lamb or beef, a little soaked bread, eggs, butter, finely chopped onion, garlic, curry powder and turmeric. All are mixed together, put in a pie dish with meat drippings, and baked in a low oven for a time. The moment the mixture begins to brown, the dish is taken from the oven and some eggs beaten up with milk are poured over the top; then the dish is put back into the oven and baked very slowly to a deep brown. The pace of the cooking is important: if the oven is too hot the bobotie will be dry, and that should never happen, for an ideal bobotie is eaten moist, over rice. (more…)

The Advent of Virgin Australia

Virgin Atlantic Airways has always inexplicably attempted a fine balance between the crisply modern and the vaguely old-school. It is also unashamedly British. When the lumbering giants at British Airways were busy banishing the Union Jack from their aircraft livery — prompting Baroness Thatcher to cover the model of a BA 747 with a handkerchief — Sir Richard Branson said “We’re British: why don’t we fly the flag?” The Union Jack was added to every Virgin Atlantic plane and a flag design was later added to the wingtips. Virgin Atlantic now has a patriotic red-head (above) bedecked in the Union flag on the nose of each of its aircraft glamourously advertising their national origins in this hyperglobalist age.

Virgin Group has not restrained itself from expanding beyond the trans-Atlantic flightpath. In 2000, they established Virgin Blue in Australia, originally flying only between Brisbane and Sydney, but gradually expanding within the country, especially after the 2001 collapse of the major domestic carrier Ansett Australia. In 2003, Virgin started Pacific Blue Airways out of New Zealand, operating trans-Tasman routes, followed by the founding of Polynesian Blue in 2005 running flights between New Zealand, Australia, and Samoa. Finally, V Australia was started operations in 2009 running long-haul flights out of Australia. (more…)

Les fondements de notre civilisation occidentale

« Les fondements de notre civilisation occidentale sont chrétiens ; le respect du christianisme est une condition sine qua non d’une droite qui veut conserver non seulement la prospérité économique, mais ce qui est au fondement de toute prospérité durable : le souci du bien commun, le respect de la loi naturelle, le sens de la justice. »

The latest issue of Égards, the premier journal of traditional conservatism in Quebec, contains an interesting analysis of the current situation faced by the various streams of the centre-droit spectrum in the province. I am, however, very much against the perpetual organisation-founding that goes on in political circles. There seems to be a belief that, when in doubt, start a new organisation, but this is precisely what the author, M. Décarie, proposes.

Dublin Diary

WE START OUT at the usual Italian place, PH’s stammtisch despite his complaints that they’re stingy and never bring you a limoncello at the end of a meal, as is custom elsewhere. The usual verbal briefings are exchanged, updating each other on the scheme of things and the general banter. It’s warm enough to sit outside, which allows us the luxury of a cigarette with our coffee as we cast aspersions on passing strangers. This quickly moves on to casting aspersions on mutual acquaintances (we will not call them friends!) and extrapolating therefrom more general condemnations of the heresiarchs and heretics of our day (chiefly: liberals, Modernist clergy, fops, les Brideshead affectés, users of inappropriate typefaces, and all people who take life too seriously).

After the postprandial coffee, we head on to Doyle’s but, just as we arrive, Brian gets in touch directing us elsewhere. We meet up with him and his three friends on the street but PH and I do not take a shine to Brian’s temporary entourage and secede from the party. Where to? Lincoln’s Inn, end of Nassau Street. (more…)

Dino Takes on Nic & Rem

Dino Marcantonio is on his usual top form when responding to an interview with the “Dutch architect and uber-gobbledegook-meister” Rem Koolhas by Nicolai Ouroussoff, the architecture praiser for the New York Times. Many modernists now find themselves in the role of perverse preservationists, trying to save ugly modernist buildings that are already falling apart because of their inherent conceptual flaws and rejection of inherited architectural wisdom. But while the Mods want to save the crumbling monstrosities, they attack the natural human instinct to preserve what is beautiful (i.e. traditional and vernacular architecture) and to destroy or get rid of what is ugly (their own work, the “ambitious” carbuncles of the past century).

Koolhaas and Ouroussoff pretend to confuse the true spirit of preservation with hoarding. A hoarder makes no value judgments about what should be kept. It all stays, and the result is his home is a dump. If we keep everything, we wind up preserving nothing–and that, my friends, is what Koolhaas is really all about. His endgame is the embalming of our architectural identity. He is suffering from an acute case of cronophobia, the irrational fear that old things might still be alive to us today.

Dino, however, is not having it:

Consider another approach taken by the Venetians toward the beautiful church Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari. Completed in the early 14th century, it has been lovingly embellished by generations and generations, all meaningfully, and without any angst about what is authentic and what is not. It has also suffered through suppression, looting, and radical restoration. I Frari has been through it all. It is almost 700 years old, yet because it has been properly cared for, it still looks fresh as a garden daisy. And it is mobbed by visitors year-round who yearn to follow its example, not only in the preservation and handing down of churches, but also our cities, our homes, our culture.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- A Christmas Gift from the Governor December 24, 2024

- Oude Kerk, Amsterdam December 24, 2024

- Gellner’s Prague December 19, 2024

- Monsieur Bayrou December 18, 2024

- Dempsey Heiner, Art Critic December 17, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories