About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Imperial Mexico

The Forgotten Monarchs that Shaped a Great Nation

THE NEW WORLD has such a republican reputation these days. Even though there remain thirteen monarchies in the Americas, concentrated in the Caribbean, there are only three monarchs between them (all, curiously, women: Elizabeth II, Beatrix, and Margrethe II). But it’s usually forgotten that the Americas have had two great empires of their own: the Empire of Brazil in South America and the Empire of Mexico in North America.

Napoleon’s Peninsular War in Spain had caused quite a ruckus in the Spanish Americas, where liberals had seized the opportunity to wage long, rebellious wars of independence with fluctuating levels of popular support. In Mexico, two of the rebel generals, Agustín de Iturbide and Vicente Guerrero composed a plan to change the balance of power in the Spanish empire as a whole while simultaneously securing Mexican independence. The three main aims of the ‘Plan of Iguala’ were: 1) Catholicism as the established religion, 2) The independence of Mexico, and 3) The end of legal distinctions between the races; summed up as “Religión, Independencia, y Unión”.

But the larger scheme of the Plan was to convince King Ferdinand VII to move to Mexico and become Emperor of Mexico, shifting the center of power in the Spanish empire from Madrid to Mexico City. If Ferdinand would not accept, then the crown would be offered to his brother and the rest of his family down the line until someone accepted, or if even that failed then to a member of another European dynasty.

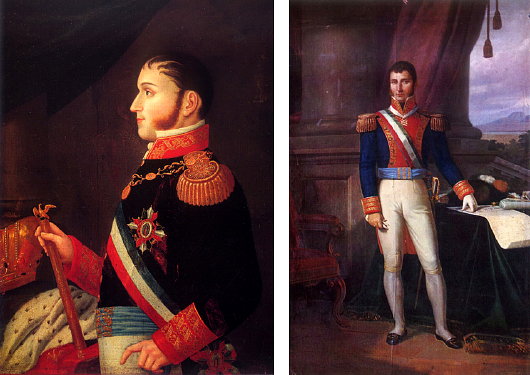

Agustín I of the House of Iturbide, Emperor of Mexico

With the royalist forces in Mexico in retreat, the Viceroy of New Spain, Juan O’Donojú y O’Rian, considered the compromise the best offer on hand for preserving Spain’s monarchic dominion in the New World. O’Donojú met with Iturbide and Guerrero and worked out the Treaty of Córdoba, establishing Mexico as an independent empire, on August 24, 1821. Until Ferdinand could be persuaded to Mexico, a regency council was established including O’Donojú, Iturbide, and Guerrero.

Ferdinand, however, had other ideas. The Cortes Generales resolved that the Treaty was illegal, null, and void, and made plans to reconquer Mexico. He forbade any member of his family from accepting the offer of the Mexican throne. Since his restoration to the throne after the Bonapartist interlude, the King’s star was in the ascendant on the European stage, and no other dynasty dared accept the perhaps tempting crown of the Mexican empire.

The Mexican solution was to find an emperor from amongst their own number, and as President of the Regency, Gen. Iturbide was the obvious choice. On May 19, 1822, the Congress proclaimed the general as their emperador. On July 21, amidst great solemnity in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Mexico, he was crowned Agustín I of the House of Iturbide, By Divine Providence and the Congress of the Nation, Emperor of Mexico.

The Emperor Agustín and the Empress Ana María

It didn’t take long for things to turn sour. Later in the year, the republican factions in the Congress began to raise a revolutionary tumult against the Emperor, and in response he dissolved the body. The newspaper of the Masonic lodges, El Sol, joined in the fray against Agustín, and the United States, disturbed by the prospect of an American Catholic empire on their doorstep, supported the rebel republicans. The economic situation turned dire because the European nations allied to Ferdinand VII refused to trade with Mexico, and the Emperor’s own mismanagement began to turn the landowning classes against him.

Faced with the opposition of liberals & republicans, the old royalists still loyal to Ferdinand, the European allies of the Spanish, and the neighbouring (and increasingly powerful) United States, Agustín’s Mexican Empire could not hold. Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna and Gen. Guadalupe Victoria launched the ‘Plan of Casa Mata’ — the abolition of the monarch and the declaration of a republic — in December 1822. The imperial forces at first put up a good show of defiance against the rebels, but the commander of the Emperor’s army turned traitor to the rebels. The Emperor sued for peace with the two generals and met their conditions. Agustín I of the House of Iturbide called a Congress and his first act after its convening was to offer his abdication. May 11, 1823, the ex-emperor boarded a Livorno-bound ship and eventually settled in England.

Iturbide’s imperial adventure was not to end there, however. The situation in Mexico only continued to deteriorate, and often contradictory reports were sent back to Europe about the possibility of a Spanish reconquest and Mexico’s willingness to receive its former Emperor. Iturbide decided to return, and landed on July 14, 1824, alongside his wife, children, and their chaplain. An enthusiastic crowd greeted his return, but he was soon arrested, tried, found guilty, and executed. The Republic was in the ascendant, for now.

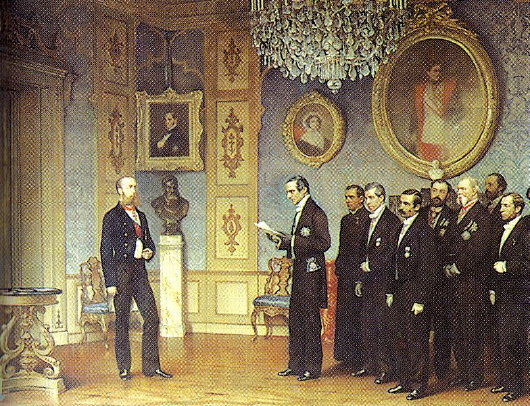

The republican regimes were no more successful at running Mexico than the Emperor; indeed worse. English-speaking settlers began to settle between the Rio Grande and the United States border and won a war that established the Republic of Texas’s independence from Mexico. Texas joined the United States in 1845, and a year later the U.S. declared war on Mexico. By 1847, the U.S. Army had captured Mexico City and the Mexicans finally sued for peace. They agreed to sell their northern territories to the United States, which now reached from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans. In 1859, a delegation of Mexican nobility and other prominent citizens (above), led by José Pablo Martinez del Rio, proposed to Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria that he become Emperor of Mexico. But the delegation had neither power nor authority, and so the Archduke demurred, preferring to organise a botanical expedition to Brazil.

The various Mexican governments had also racked up a large debt from various European powers. In 1861, the governments of Great Britain, France, and Spain concluded a treaty agreeing a united course of action in seeking loan repayments from Mexico. The three powers blockaded Mexican ports and landed small forces. Soon, however, Napoleon III ordered a full-scale invasion of Mexico — Britain and Spain realised the whole enterprise had been a cover for French imperial ambitions and subsequently pulled out of the endeavour. While the French troops suffered an initial defeat at the Battle of Puebla, still celebrated by Mexicans as Cinco de Mayo, more soldiers poured into the country. Over the course of a year, during which the French Foreign Legion arrived and fought their legendary Battle of Camarón, the French made steady success until they finally entered Mexico City on June 7, 1863. A junta of Mexicans was promptly organised to declare an Empire, and the proposal to Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian was made yet again.

The Archduke was an intriguing man. He was the second son of the second son of the Austrian emperor (even though his elder brother Franz-Josef eventually inherited the throne). He was interested in the sciences, especially botany, and was made commander of the Austrian navy at twenty-two. In 1857 he married Princess Charlotte of Belgium, the daughter of King Leopold I, and orchestrated the Novara scientific expedition of 1857–1859 which completed the first Austrian circumnavigation of the globe.

Maximilian I, Emperor of Mexico

With the French army in control of most of Mexico, the imperial proposal was deemed acceptible. As the French continued to battle the republican forces of Benito Juárez, the Archduke landed at Veracruz on May 21, 1864 and was proclaimed Maximilian the First, Emperor of Mexico. Unfortunately, the continued political instability meant that plans for a great coronation in the Metropolitan Cathedral had to be shelved. Maximilian and Carlota chose Chapultepec Castle as their imperial residence, and ordered the construction of the Paseo de la Emperatriz from there to the Zócalo at the center of the city. Childless themselves, the imperial couple adopted two grandsons of Agustín I as their own children: Don Agustín de Iturbide y Green, intended to be the heir, and his cousin Don Salvador de Iturbide y Marzán.

The Emperor at first proved to be a disappointment to the conservatives, as he upheld the land reform proposals and the extension of the electorate to non-landowners. Maximilian was concerned not with his own vanity or power but with first securing the peace in Mexico. He offered an amnesty to Juárez if he would swear allegiance to the Crown, and even offered to make him prime minister, but Juárez refused.

Before the Emperor had time to consolidate his rule, a surprisingly disadvantageous event happened to the northeast: the American Civil War ended. Maximilian welcomed thousands of Confederate refugees and offered them grants of land, as he did to other settlers from Austria and the German lands. But now that the Civil War was over, the government of the United States began to set their sights on destabilising the Mexican Empire. They sent arms to Juárez and his ally Porfirio Diaz, who hypocritically condemned the Emperor’s rule as a foreign intervention in Mexican affairs. Despite having just concluded the most bloody war in American history, the government in Washington then ordered a significant buildup of troops along the frontier with Mexico, to give the impression of preparing an invasion.

The cost to Napoleon III of maintaining an army in Mexico grew ever more costly, and the French emperor was distracted by an increasing obsession with his rivals, the Prussians. When Napoleon III decided to withdraw his troops from Mexico, Maximilian sent the Empress Carlota to Europe to try to convince him to change his mind. She sought assistance for Mexico in Paris, Vienna, and Rome, but was unsuccessful everywhere in obtaining anything but sympathy, and suffered a nervous breakdown at her failure.

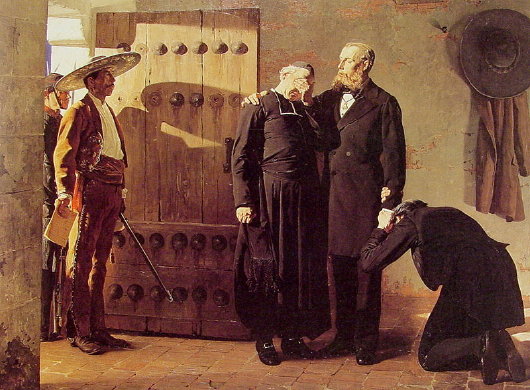

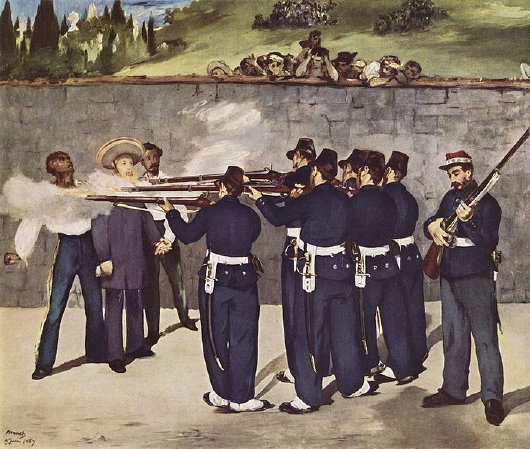

Napoleon III urged Maximilian to quit Mexico, but he refused to abandon his faithful supporters, who were still numerous. Numerous, but unlucky in battle, and demoralised by the withdrawal of the French. Maximilian was captured by republican forces on May 16, 1867, and subsequently tried and sentenced to death. The sentence caused an outcry all over Europe, and even liberals like Victor Hugo and Giuseppe Garibaldi sent appeals for the Emperor’s life to be spared, but Juárez refused them all.

June 19, 1867 was the day appointed for the imperial execution. Still thinking not of himself but of others, he uttered his last words aloud: “May my blood be the last to flow for the good of this land. ¡Viva Mexico!”

The Emperor’s final thoughts, however, were of his poor wife who was never to return from Europe. Before the executioners opened fire, Maximilian was heard to utter “Poor Carlota”. The Empress survived, living until 1927, but the last Empire of Mexico was gone. The Emperor’s body was taken back to Austria aboard SMS Novara, the same ship whose circumnavigation of the globe he had organised.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

- Waarburg October 2, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

“By 1847, the U.S. Army had captured Mexico City and the Mexicans finally sued for peace. They agreed to sell their northern territories to the United States, which now reached from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans.”

In fact the US had had a Pacific coastline since at least the Oregon Treaty with the United Kingdom one year earlier:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oregon_Treaty

Andrew,

Good writing with one flaw, namely-how appropriate-the Elizabeth !! you refer to is actually Elizabeth 1 of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The ‘virgin queen’ Elizabeth reigned before the union of Crowns And Parliaments.

The English can perhaps be forgiven this arrogance but not you Andrew, educated at St Andrews, really!

But the monarchies in question are all former English colonies, not former Scottish ones, so I’m afraid Elizabeth the Second it is.

Perhaps Elizabeth I of Darien?

The distinction of what constituted English as in the English Crown became fudged after 1603 and the accession of James V1 of Scotland but by 1707 it was fait accompli, palms were greased with English gold and Britain was born.

Elizabeth Windsor is the first Elizabeth of Britain.

This will run and run.

Thanks for this series. You seem to be able to impart a kind of elegiac attractiveness to places and events. Their history is sad, but it might be that many “average” Mexicans enjoy a life that is good in the Thomistic sense of the term. It is one of the places I entertain as a possible home away from the political and economic madness of the U.S. I’m looking at Vera Cruz–do you know of any sources of information on what I might expect the place to be?

Andrew, Thank you very much–I learned from this, as is usually the case when I read your posts.

It would be interesting someday to read more about the attitude of President Monroe towards Emperor Agustín I. But it does appear that, once again, negative US attitudes towards Catholics had a baleful effect.

Since 1917 half of the Virgin Islands have no longer been Danish so I am a bit puzzled at the ref to Margrethe II as a monarch in the Americas. Can someone enlighten me?

Greenland.

Baie dankie, Andre. Ek het vergeet dat Groenland is die eiendom van Danmark.

Plesier!

Agustín de Iturbide y Green lived on until 1925. He became a professor of Romance Languages at Georgetown.

All very interesting. Years ago I read a bit about Maximilian and his hapless wife, but the material about Iturbide was all news to me. I hope that it can be turned into an article (maybe with footnotes?) and published in some hard-copy magazine.

Interesting that you should post this and other beautiful entries on Mexico just as the Dallas Symphony of which I am a member is presenting this weekend an enjoyable program of Latin American (mostly Mexican) music under the direction of Alondra de la Parra…

http://www.alondradelaparra.com/

http://dallassymphony.com/Ticket/ProductionDetail.aspx?perf=19907&selected=881