2010 January

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Old Master & 19th Century at Christie’s

Being something of an auction-house dilettante — I last brought you a virtual update from the Dublin bidding chambers — there are a number of works up for grabs in tomorrow’s Old Master & 19th Century Paintings, Drawings, and Watercolors auction at Christie’s here in New York that caught my eye. A few other items sold in recent auctions follow at the bottom. (more…)

The Patriarchal Cathedral Basilica of Saint Mark the Evangelist, Venice

One of the readers over at the NLM sent in these photos of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. The reason why St. Mark’s is usually referred to as a mere basilica is because for centuries this was not the seat of the Patriarch of Venice. From the seventh century, the Church of San Pietro di Castello was the cathedral of Venice, while St. Mark’s was the house church of the Doge, the elected duke of the Venetian aristocratic republic. It was only in 1807 that St. Mark’s was made the cathedral of Venice, and San Pietro di Castello reduced to co-cathedral status. But by the time St. Mark’s became a cathedral, everyone had already become accustomed to referring to it as “St. Mark’s Basilica”. (more…)

Question for Cusack?

A long-time reader suggests “If your readers could put any question to you, what do you think they would ask?” Well, I have no clue, but it seemed like an intriguing idea to find out. If you have a question — any question, on any subject from breakfast to boomerangs, so long as it’s decent — send along an email to the address given in the right-hand column, making sure to have ‘QUESTION FOR CUSACK’ in the subject line. The best, most interesting, illuminating, simplest, and strangest questions will be chosen and answered in due course.

In the mean time, this blog is going on a temporary hiatus (UPDATE: or rather, by the end of this week). I have made use of my gradually accumulated hoard of frequent-flyer miles and in just over a week I will be fleeing to Britain for a fortnight, hoping to advance somewhat on the job front, or at the very least lay the foundations for such an advance. I should return within the octave of Saint Valentine, and I hope the various blogs, sites, and journals in our sidebar will provide some stimulation and interest for you until that point.

Send a shekel or two

The reader will be happy to note that he owes this blog absolutely nothing. We provide no services nor supply any goods. We merely, like the creatures of old, exist and (God willing) will continue to exist. Nonetheless, little corners of the web such as our own do require some small monetary resources to make up for the cost of maintenance, and the frightening “domain-renewal” warnings from “service providers” have already reached our electronic pigeonhole. I should be rather embarrassed if the forces of subversion and revolution take hold of our precious andrewcusack.com, and you & I both be forced to flee for some other pasture, but this can easily be prevented should those few amongst you who are not beset by perils in “the current economic climate” send a shekel or two towards the maintenance fund. A little token of appreciation for all our munificent benefactors is currently in the planning stages.

P.S.: If exigencies do force this little corner of the web to close, rest assured that most of its information has been downloaded and saved, so that it can be uploaded again should the time come when that is appropriate.

The Dovecot at Alphen (1989)

ESTABLISHED in 1714, Alphen is one of the legendary estates of the Cape Peninsula: Dr. James Barry duelled on the south terrace with Josias Cloete, and its guests include the illustrious names of Mark Twain, Cecil Rhodes, Field Marshal Smuts, and many more. While it once covered most of northern Constantia, the estate was much reduced during the twentieth century (and the M3 Simon van der Stel Freeway was built through its vineyards), Alphen, now a country-house hotel, is growing once again in the hands of the latest generation of Cloetes.

In 1989, the council authorities visited Alphen and declared that an electric substation must be built on the site or the hotel be forced to close. The ancient electric supply lines had, it turned out, been constructed illegally, and there was some danger of fire unless a substation was built on the Alphen property itself.

“Horrified we said there must be some other way,” writes Nicky Cloete-Hopkins (in the Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Society of South Africa). “There wasn’t, and Dudley [Cloete-Hopkins] said to Dirk [Visser, architect], who had been working with us for about five years by that time, ‘Disguise it as a folly or something.’”

“The ideal site for ours was … on the banks of the Diep River, at the end of a path leading from the 1772 water mill. It was in line with the strict grid pattern of the farm complex and gardens, much of which had been destroyed in the early and mid part of the twentieth century. We briefed Dirk to have fun, create a ‘folly’ and incorporate the Mitford-Barberton crucifix and family plaques from a Garden of Remembrance, demolished after the farm was subdivided.” Ella Lou O’Meara was later commissioned to do a family tree in tile for the Garden wall.

“Dirk suggested the dovecote — although we have had difficulty in keeping doves there. A little flamboyance has often enhanced the severity of the architecture at Alphen, and Dirk’s sketches for the proposed dovecote delighted us.”

Alphen and its great square of farm buildings had been designated a National Monument — akin to landmarking in the U.S. or listing a building in Britain — and so changes or additions needed to meet with the approval of certain historic advisors. “The builders had nearly completed their work when the then National Monuments Council sent representatives to inspect it. They commented that the design was not ‘honest’ and that we were fooling the public in making it look like a historic building.”

Mrs. Cloete-Hopkins wondered if the NMC wanted them to build something horrifically functional in the middle of a historic site for the sake of “honesty” or whether they wanted them to “erect something ultra-modern” like the new Louvre pyramid that was causing controversy at the time. “In any event it was too late to look at alternatives and I happily satisfied requirements by putting the date and the name of the architect and builder on the side of the building.”

A wise compromise and, like the dovecot/substation itself, informed by precedent.

Dino Marcantonio Hath a Blog!

Dino Marcantonio, habitual luncheon companion of your humble & obedient scribe, not to mention frequent commenter upon this little corner of the web, has entered into the realms of blogging himself. You can find his musings on the theory and practice of architecture here. They make for some pretty good reading so far.

An Old Dutch Holdout

The sign on the façade of No. 7 Wale Street, Cape Town in this 1891 photo informs us of its status as a police station in the two official languages of the day, English and Dutch, not Afrikaans. ‘Politie’ is the Dutch word for Police, while the Afrikaans is ‘Polisie’. Afrikaans only became an official language of South Africa in 1925, but was so alongside Dutch and English until 1961, when Dutch was finally dropped.

This beautiful old Dutch townhouse, with its typical dak-kamer atop, didn’t survive as late as 1961. The Provinsiale-gebou, home to the Western Cape Provincial Parliament, was built on the site in the 1930s. Those who viewed the 2009 AMC/ITV reinterpretation of “The Prisoner” might remember an outdoors nighttime city scene after the main character leaves a diner, with the street sign proclaiming “Madison Ave.” and plenty of yellow New York taxicabs streaming past. The large arches in the background are the front of the Provinsiale-gebou.

A Selection of South African TV Ads

You can probably deduce a great deal about a country from its television advertisements: its sense of humour, its values perhaps, maybe even its sense of itself. Below are a cross-section of South African television ads, all of them leaning towards the humourous end of the marketing spectrum. I’ll let the reader come to his own conclusions. (more…)

“Nothing between the insulting and the superlative…”

« In the restaurant on the Rue Saint-Augustin, M. Mirande would dazzle his juniors, French and American, by dispatching a lunch of raw Bayonne ham and fresh figs, a hot sausage in crust, spindles of filleted pike in a rich rose sauce Nantua, a leg of lamb larded with anchovies, artichokes on a pedestal of foie gras, and four or five kinds of cheese, with a good bottle of Bordeaux and one of champagne, after which he would call for the Armagnac and remind Madame to have ready for dinner the larks and ortolans she had promised him, with a few langoustes and a turbot — and, of course, a fine civet made from the marcassin, or young wild boar, that the lover of the leading lady in his current production had sent up from his estate in the Sologne.

“And while I think of it,” I once heard him say, “we haven’t had any woodcock for days, or truffles baked in the ashes, and the cellar is becoming a disgrace — no more ’34s and hardly any ’37s. Last week, I had to offer my publisher a bottle that was far too good for him, simply because there was nothing between the insulting and the superlative.” »

Relic of Blessed Charles in Catalonia

In October of last year, a relic ex ossibus of Blessed Charles I was formally received at the Basilica Church of Our Lady of Mercy & St. Michael Archangel in Barcelona, the capital city of the Spanish principality of Catalonia. The bone fragment is the first relic of the last Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary, and King of Bohemia to be publicly venerated in the Kingdom of Spain. It was requested by His Grace the Bishop of Solsona, Don Jaume Traserra y Cunillera, at the request of the Catalonian Delegation of the Constantinian Order. The relic has been enshrined in the chapel of St. Michael the Archangel, alongside a portrait of the Emperor.

A grandson of Blessed Charles, HIRH the Archduke Simeon of Austria, attended (with his wife) as the representative of HRH the Infante Don Carlos, Duke of Calabria, the Grand Master of the Constantinian Order and head of the Royal House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies. Also in attendance were Lt. Gen. Don Fernando Torres Gonzalez (Army Inspector General), General Mainar Don Gustavo Gutierrez (Chief of the 3rd Sub-inspection Pyrenees and Military Commander General of Barcelona and Tarragona), as well as representatives of the Order of Malta, the Order of the Holy Sepulchre, various guilds and corps of Spanish nobility, and lay fraternities.

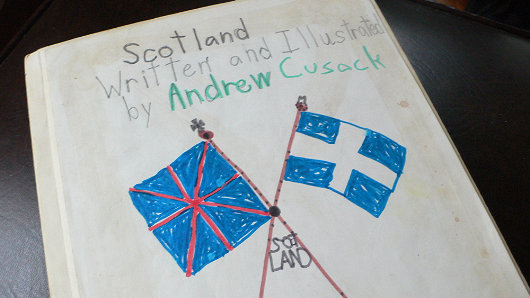

Scotland

Written and illustrated by Andrew Cusack (at 7 years of age)

Were I to review this book, I would say it is riddled with inaccuracies and depicts a stereotypical Hollywood version of Scotland far-removed from reality. But then, it was written in 1991 by a seven-year-old (yours truly), which is already eighteen years ago now. The ultimate schoolboy error is that I was apparently incapable at age 7 of producing a vexillologically accurate reproduction of the Saltire. My incorrect version of the Scottish appears like the old Greek flag, a white cross extended across a blue field. (See the correct flag here). (more…)

‘The Splintering Rainbow’

The veteran South African journalist Rian Malan last year made a documentary for Al Jazeera on recent events in the country. It’s an interesting and well-balanced programme that presents multiple points of view. Importantly, it avoids the all-too-frequent stereotyping of the Mbeki/Zuma rivalry. It also includes a scene of Hellen Zille speaking (in English) to Stellenbosch students in the Sanlam Saal of the Neelsie.

The 45-minute documentary is available in four parts on YouTube below. (more…)

Stoddart’s Ode to Ossian

The Queen’s Sculptor Plans Great Literary Monument in the West of Scotland

Word reaches me that Alexander Stoddart, the Queen’s Sculptor in Ordinary for Scotland, has dreamed up a massive monument to Ossian. “For fifteen years Stoddart has planned ‘a national Ossianic monument’ on the west coast of Scotland,” writes Ian Jack in The Guardian. “The scale is immense. Stoddart wants a great amphitheatre cut into the rock with Ossian’s dead son, Oscar, also cut from rock, prone on his shield on the amphitheatre’s floor.” The project would be the biggest literary monument in the world, surpassing the Scott Monument on Princes Street in Edinburgh. It could be the project of a lifetime for Stoddart.

“He says a lot of people are keen, including Scottish government ministers, landowners and historians, and that a site has been identified in Morvern and a preliminary survey completed by the engineers Ove Arup. There is also environmental opposition: the kind of people, according to Stoddart, who will ‘always find two mating ptarmigan no matter where we choose’ and haven’t taken into account Schopenhauer’s view that ‘the sound of nature is the sound of perpetual screaming’. It may account for the two death threats he says he has received.”

“The Ossian poems, especially ‘Fingal’, took Europe by storm,” the journalist continues, “and gave it a new notion of the savage and sublime. A cave on Staffa became ‘Fingal’s Cave’. Goethe incorporated Ossian into The Sorrows of Young Werther and Schubert used passages of Goethe’s translation in his lieder. By Stoddart’s estimate, nothing, not even the work of Burns, has made a larger Scottish contribution to European culture. Ossian established the Scottish wilderness as a destination for Europe’s earliest tourists. Also, by ennobling Celtic antiquity, it changed Scotland’s sense of itself.”

The traditional style of Alexander Stoddart, an avowed neo-classicist, has provoked foaming at the mouth in the rather dull arts establishment, but his works — such as the David Hume statue on the Royal Mile and the frieze on the Sackler Library at Oxford — have proven popular. Scotland’s greatest living sculptor has completed a bust of Scotland’s greatest living composer, James Macmillan, as well as of Britain’s greatest living philosopher Roger Scruton. (The old-school lefty Tony Benn — another living national institution — is the subject of a Stoddard bust as well).

“The paradox is that, by revering and understanding abandoned traditions, [Stoddart] has emerged as one of the most original artists in Britain: a stranger to his times.”

Early Morning, Madison Square

Charles Courtney Curran, Early Morning, Madison Square

Oil on canvas, 22 in. x 18 in.

1900, National Arts Club, New York

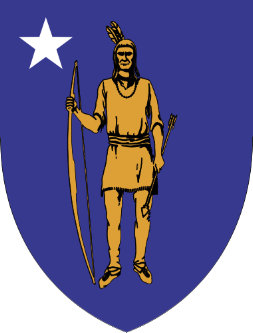

The Coat of Arms of Massachusetts

Massachusetts is all over the news of late as the northerly state holds a special election to fill the seat left empty by the death of the notorious Senator Edward Kennedy. The Democratic Party outnumbers Republicans by three to one in the land, but their candidate is fighting tooth-and-nail against the G.O.P. challenger. Crucially, half of Bay State voters are independents, and the Republican candidate is polling well among floating voters. But, of course, the pedantry of politics does not normally fall under the purview of this little corner of the web. Rather, let us consider the heraldic achievement of the Bay State. The most handsome and successful arms are marked by their simplicity. (For a host of excellent examples, consult the roll of Sweden’s provincial and town arms). The heraldry of the American states can tend toward the over-complicated, but the coat of arms of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a noble exception.

Massachusetts is all over the news of late as the northerly state holds a special election to fill the seat left empty by the death of the notorious Senator Edward Kennedy. The Democratic Party outnumbers Republicans by three to one in the land, but their candidate is fighting tooth-and-nail against the G.O.P. challenger. Crucially, half of Bay State voters are independents, and the Republican candidate is polling well among floating voters. But, of course, the pedantry of politics does not normally fall under the purview of this little corner of the web. Rather, let us consider the heraldic achievement of the Bay State. The most handsome and successful arms are marked by their simplicity. (For a host of excellent examples, consult the roll of Sweden’s provincial and town arms). The heraldry of the American states can tend toward the over-complicated, but the coat of arms of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a noble exception.

The central motif of the Indian with bow and arrow has appeared almost consistently from the beginning. A native appears in the seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, in which the appeal “Come over and help us” pours from his lips. The arms of the neighboring Plymouth Plantation likewise depicted a native, in Plymouth’s case quartered between the arms of a Cross of St. George. Disregarding the earlier attempt to form the Dominion of New England, the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Plymouth Colony were finally united in the Province of Massachusetts in 1691, and received a seal depicting the English royal arms.

Late in 1774, revolutionaries established the Massachusetts Provincial Congress to subvert legitimate authority in the province, subversion which erupted into open warfare in April of the following year. The rebels created their own emblem depicting an English colonist instead of an Indian, now armed with a sword and a copy of Magna Carta. The motto Ense petit placidam sub libertate quietem (“By the sword we seek peace, but peace only under liberty”) was chosen, a quote attributed to the English republican Algernon Sydney.

In 1780, the rebel provisional government adopted a new device created by Nathan Cushing. The Cushing design resurrected the Indian, and added a single star symbolizing the province’s statehood to accompany the native. Paul Revere engraved the design, the original impressions of which are preserved in the Archives of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (more…)

Haiti

Readers will by now have doubtless heard of the immense devastation that has been wreaked upon Haiti by yesterday’s earthquake. There may be as many as hundreds of thousands of dead and the level of destruction is appalling. Among the many buildings destroyed is the Cathedral of Port-au-Prince, and its archbishop, Joseph Serge Miot, has been confirmed as dead. The first of Malteser International’s medical teams will arrive tomorrow (Thursday) to provide emergency relief to the people in Haiti. Donations towards the Order of Malta’s earthquake relief efforts can be made here.

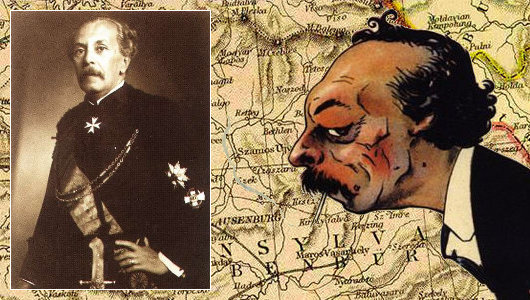

‘The Tolstoy of Transylvania’

In his column in the Daily Telegraph, former editor Charles Moore praises Miklos Banffy as ‘the Tolstoy of Transylvania’. Ardent Banffyites like myself are always pleased when the Hungarian novelist gets attention in the English-speaking world, which happens all too rarely. I can’t remember how on earth I stumbled upon the works of Banffy, probably through reading the Hungarian Quarterly, a publication that — covering art, literature, history, politics, science, and more — is admirably polymathic in our age in which the specialist niche is worshipped.

To put it simply, Banffy is a must-read. If you love Paddy Leigh Fermor’s telling of his youthful walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople (the third and final installation of which we still await), then Miklos Banffy will be right up your alley. Start with his Transylvanian trilogy — They Were Counted, They Were Found Wanting, and They Were Divided.

The story follows two cousins, the earnest Balint Abady and the dissolute László Gyeroffy, Hungarian aristocrats in Transylvania, and the varying paths they take in the final years of European civilization. The novels “are full of love for the way of life destroyed by the First World War,” Charles Moore points out, “but without illusion about its deficiencies.”

Three volumes of nearly one-and-a-half thousand pages put together, they make for deeply, deeply rewarding reading, transporting you to the world that ended with the crack of an assassin’s bullet in Sarajevo, 1914.

After finishing his trilogy, Banffy’s autobiographical The Phoenix Land is worthwhile; some of the real events depicted shadow those in the fictional novels. As previously mentioned, it contains a description of the last Hapsburg coronation (that of Blessed Charles) and numerous amusing tales.

After that, I’m afraid you will have to learn Hungarian, which I have neglected to do, as no more of this author’s oeuvre has yet been translated into English.

When an American aristocrat meets a European Grand Duke

Mother Margaret Georgina Patton, OSB of Regina Laudis Abbey in New England is the daughter of Gen. George S. Patton IV and granddaughter of the famous Gen. George S. Patton III. Mother Patton remembers being introduced to the Grand Duke of Luxembourg when she was but five years of age. At the instruction of her parents, she spent a week practicing her curtsey. When the moment finally came and she was brought before His Royal Highness, she looked him over, and stuck out her hand. The young girl had expected a crown, and, seeing none, thought a regular old handshake would do.

The elder Gen. Patton did have a connection to the Abbey himself. “General George Patton, Sr., liberated France as the commanding general of the Third Army,” explains Mother Delores Hart (the former film actress, and only nun among the members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences). “His was the army that liberated Jouarre, the abbey where Mother Benedict was in hiding.” Mother Benedict Duss founded the Abbey of Regina Laudis after the war, and died at the ripe age of 94.

“This connection continues through the whole Patton family to this day,” Mother Delores continued. George S. Patton V lives close to the Abbey in Connecticut, with his brothers Robert H. Patton in nearby Darien, and Benjamin Wilson Patton in New York, while their sister Helen lives in Saarbrücken, Germany.

General Patton père died in a car accident in Germany, but his son followed in his footsteps by choosing a career in the army. When his daughter Margaret, the future nun, was born, he was fighting in the wilds of Vietnam. Nonetheless, General Patton fils felt compelled to write a letter to his newborn daughter, introducing himself from abroad. He ended it simply “Play it cool” and signed his full name.

It’s no wonder that Margaret joined Regina Laudis, a community of Benedictines in full, traditional habits, as she came from a well-dressed family. General Patton père designed his own uniforms and even the family of the younger general continued the tradition of dressing for dinner, “despite the trend toward informality that was sweeping the nation” as the Patton Saber puts it. The old habits are returning — any bets on when folks will start dressing for dinner again?

Joyce Linton: The Lady with the Voice

Yesterday, in a beautiful sung requiem at St. Agnes, we paid our final respects to our friend Joyce Linton. I had known Joyce for quite some time before I ever actually met her because we tended to sit in the same neighborhood of pews (in the back of the church towards the left) at the 11 o’clock Mass at St Agnes every Sunday. While a schoolteacher by profession, she was also a trained vocal musician, and her voice carried as the congregation belted out our Credos and Glorias. She became known to me as “the Lady with the Voice”, and every so often I would see her making her way towards the church just before 11:00 and, without knowing her name, I would say to myself “That’s the Lady with the Voice”.

Eventually, I got to know Joyce well, and joined the regular tea-drinking crowd of which she was a devoted and prominent member. Vim. Moxie. Determination. Those are the words that come to mind when I think about Joyce, a spirited lady if ever there was one. But she was, also, a woman with a certain style. Think of 1950s New York, swanky, bright, and modern, but still traditional, and never out of date. That was Joyce.

Now, if there was one thing that undoubtedly went along with Joyce’s vim, moxie, and determination, it was that she had an opinion. She enjoyed a vibrant discussion and the interaction of ideas, but she made certain that even if you didn’t happen to share her opinion, you would at least be familiar with it. As it happens, Joyce and I were lucky enough to agree with one another on many things, but by no means all things. More than once did I attempt to refute her position on this, that, or another thing. After the back-and-forth had exhausted itself, she would say, “Well, I don’t think it’s quite as simple as that”, I would shrug my shoulders and say “Perhaps”, and we would sip our tea and rejoin the larger conversation.

She was a woman who was grateful for the graces in her life. She was grateful for the blessings of her family, though it was not without hardships. She was grateful for the magnificent inheritance of centuries of art and culture she was born on the receiving end of. She was a patriot if ever there was one — a proud American, but one with a devoted filial love of Europe, and especially of Italy.

I think the first time Joyce visited Italy was when she did her voice studies in Florence in the 1970s, and she never stopped going back. She had a devotion to Padre Pio and paid her respects to the great saint by pilgrimming to San Giovanni Rotondo. Towards the later years of her life she had a special love and appreciation for summer days spent at Gardone on the shores of Lake Garda, enjoying the intellectual stimulation of the annual summer symposium organized by the Roman Forum. The Italian airs invigorated her Celtic blood and she would return to New York in late summer rejuvenated and refreshed.

She always knew lots of things about New York. You can get great freshly baked bread here. They do a good brunch there. If you really want to do X, then you’ve got to Y at Z on Nth Street. I remember one drizzly November Sunday afternoon Joyce showed me “the best way to cut through Saks” as she and I made our way to the annual Choral Evensong & Flag Service for the Patriotic, Historical, and Hereditary Societies at the Church of St. Thomas, Fifth Avenue.

Joyce loved her job as a high school teacher at Manhattan Center on the Harlem River, just a few doors away from Our Lady of Mount Carmel on 115th Street. Any and all bureaucratic encroachments upon the teaching profession were vociferously opposed by her, and she had an enormous pride when her students did well (especially her girls). Latin was another excuse to spend time in Italy, where she studied the language under the famous Fr. Reggie Foster in Rome. She taught English as well, and was adamant that her students learn important lessons from writers like Orwell and Wilde, rather than a rote set of facts or ideas or quotes. She was always on the lookout for a new way of explaining the old truths to the students in her charge. She loved them, but she also loved her colleagues, and more than once had us praying for this one or that one.

When she was first diagnosed with cancer, many of us prepared ourselves mentally for The End. I think Joyce said to herself “Well I’m not having any of that.” She beat it the first time round (remember what I said about vim, moxie, determination?) to the surprise of many, probably her devoted doctor most of all. She went back to work, and her own hair grew back, allowing her to dispense with the peppy wig she had specially styled. Life, it seemed, returned to normal, for one last Halcyon day before the Hour approached. When the time did appear on the horizon, her descent was rapid. I’m glad I had a chance to see her one last time, surrounded as she was by friends in Lenox Hill Hospital.

Joyce would have loved her requiem, the priest in mournful black trimmed by resplendent gold, acolytes and torch-bearers aiding in the sanctuary, the Dies Irae rising from the choir loft, and those who knew and loved her pleading God’s mercy and quick remission of her earthly transgressions. It was beautiful — as the most beautiful things are — because it pointed towards that Heavenly place from whence our only glories come, where we pray “the Lady with the Voice” will enjoy perpetual light and rest eternal.

Requiescat in pace.

Amen.

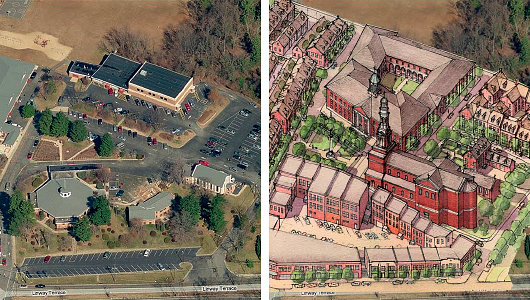

From Parking Places to People Spaces

Transforming a Suburban Parish into a Traditional Neighborhood

The widespread unsightliness of suburban development in the United States is one of the most significant counts one can hold against the country. The earliest suburbs, or indeed any that are pre-war, came out fairly well by contrast. One of the pleasures of living in Westchester is our system of verdant parkways (from the inter-war period) with arched stone bridges spanning the little creeks and carrying local thoroughfares over the road. The transformation of Long Island, after the Second World War, from countryside to row after row of mass-produced cookie-cutter homes was disastrous. (Levittown is my personal vision of Hell — identical homes completely divorced from any sense of livable social order.) Post-war suburban development combines ugliness, boringness, and an astonishing misuse of available land. Erik Bootsma, however, here presents a model proposal of how to transform the medium-sized property of a modern suburban parish church in Virginia into a small, livable neighborhood. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories