About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Parliament of the Venerable Island

Geoffrey Bawa’s Sri Lankan Parliament at Kotte

CEYLON IS AN ancient island whose history spans the epochs of human existence: palaeontologists estimate it has been inhabited for over 34,000 years. A series of ancient and medieval native kingdoms have ruled this island over the centuries before foreigners from abroad decided to enter the game. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to stake a claim here, followed by the Dutch Republic. And, yes, as with almost every place of intrigue and tradition, even Ceylon belonged to the Hapsburgs at one point: from 1580 to 1640. Native kingdoms persisted nonetheless, even while European powers bickered over their own portions of the island.

It was in 1815 that the Chiefs of the Kandyan Kingdom agreed to depose their own monarch, Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, and place George III of the House of Hanover on the throne. Ceylon was united at last, and — after the end of the Kandyan Wars — the island enjoyed relative peace and prosperity during one-hundred-and-thirty-three years of British rule.

In 1948, the British granted independence to the Dominion of Ceylon. The island continued as an independent constitutional monarchy for much longer than its neighbours India and Pakistan. The rudiments of a two-party system emerged, with the United National Party bringing together the conservative, traditional element in political society, while the Freedom Party advocated non-revolutionary socialism.

The population of Ceylon, however, are a complete hodgepodge of ethnicities. The largest group are the Sinhalese, a Buddhist people constituting over 70% of the population. But at the northern end of the island, the Tamil people were dominant, even though these were split between “Ceylonian” Tamils native to the island and “Indian” or “Plantation” Tamils brought during British rule to work the large plantations. Then there are the Moors, a multiracial Muslim community of primarily Arab and Malay descent. And, of course, there are the famous Burgher people, descendants of the island’s Portuguese, Dutch, and English mixed with Sinhalese, Tamil, and Creole.

Democratically elected politicans replaced English (the intercommunal lingua franca) with Sinhala (the language of the Sinhalese majority) as the official language, abolished the Senate, severed appeal to the Privy Council and, in 1970, abolished the monarchy. The Dominion of Ceylon was renamed the Republic of Sri Lanka — the name literally means “Venerable Island”. Left-wing nationalists continually stoked tensions with the country’s conservatives, traditional elite, and minorities, and provoked right-wing reactions. Aside from the left-right divide, Tamil extremists began an anti-Sinhalese terror campaign that increased the oppression of the Tamil people and strengthened the country’s divisions. In short, it all became a mess.

Amidst this sad descent into violence, it was decided that the Parliament Building in Colombo lacked the necessary security arrangements. Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa obtained the consent of Parliament to relocate the national legislature to a new administrative center called Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte, just beyond the eastern suburbs of Colombo. The task of designing the country’s new parliament was given to Sri Lanka’s most eminent architect, Geoffrey Bawa.

Bawa’s story is, in many ways typically atypical of Sri Lanka. His grandfather was a Muslim lawyer who married an Englishwoman of Huguenot extraction. Their son became one of the most prominent lawyers in Colombo, and married a Burgher lady of Dutch & Sinhalese descent. Geoffrey was born in 1919, and left to study English at Cambridge before completing his own legal studies in London. After the end of the Second World War, Bawa became disenchanted with the prospect of a legal life and spent a year travelling the world; first throughout the Orient, then across the Pacific to America, and finally around Europe. A stay in Lake Garda convinced him of the beauty of Italy, especially of Italian architecture and landscaping.

Bawa returned to an independent Ceylon, bought a derelict rubber plantation and planned to transform it into his own tropical version of an Italian lakeside garden. As his interest in architecture grew, he took an apprenticeship with the Colombo firm of Edwards, Reid, and Begg before transferring directly into the third year of studies at the Architecture Association’s school in London. His final year was spent in Rome, where he completed his disseration on the German Baroque architect Johann Balthasar Neumann.

The early work of Geoffrey Bawa is best described as “tropical modernism”, attempting to adapt the ideas of Le Corbusier to a tropical setting. The results were mixed, but as Bawa the architect matured, he began to exhibit a greater appreciation of the Sri Lankan vernacular in his work. Terms like “contemporary vernacular” and “contextual modernism” became the bywords of Bawa.

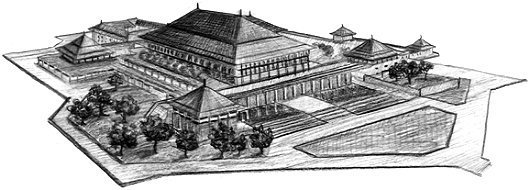

Having been commissioned by Parliament to design its new home, Bawa took several helicopter flights over the site to determine how it could best be used. He proposed the marshy land be flooded to create an artificial lake, placing the parliament building on the high ground at the center, on a 12-acre island in the middle of the lake.

In his own words, Bawa “conceived of the Parliament as an island capitol surrounded by a new garden city of parks and public buildings. Its cascade of copper roofs would first be seen from the approach road at a distance of two kilometers floating above the new lake at the end of the Diyavanna valley.”

“The design placed the main chamber in a central pavilion surrounded by a cluster of five satellite pavilions. Each pavilion is defined by its own umbrella roof of copper and seems to grow out of its own plinth, although the plinths are actually connected to form a continuous ground and first floor. The main pavilion is symmetrical about an axis running north-south through the debating chamber, the Speaker’s chair and the formal entrance portal.”

“But the power of this axis and the scale of the main roof are diffused by the asymmetric arrangement of the lesser pavilions around it. As a result, the pavilions each retain a separate identity but join together to create a single upward sweep of roofs. The use of copper in place of tile gives the roofs a thinness and the tent-like quality of a stretched skin.”

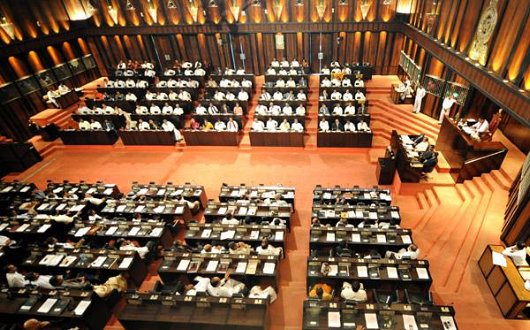

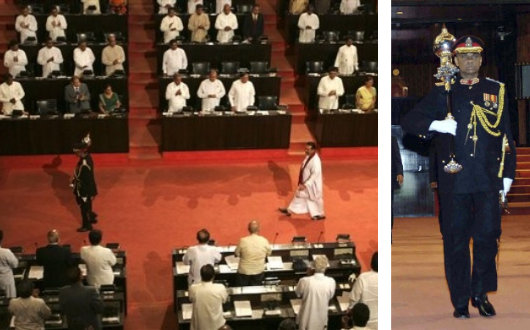

Because Ceylon spent a comparatively long time as a Commonwealth realm of the House of Windsor, many traditions of Britannic origin remain. Remembrance Day is still commemorated each November in Sri Lanka (c.f. here), in memory of the thousands of Lankans who made the ultimate sacrifice for the freedom of the Empire as well as in the country’s internecine civil conflicts. While semicircles are all the vogue in modern parliament buildings, Geoffrey Bawa’s designed retained the more traditional antiphonal arrangement so widespread throughout the Commonwealth, and recently discussed here. When the President addresses Parliament, he is preceded into the chamber by the uniformed mace-bearer carrying the body’s mace.

The President’s most recent address to the Parliament of Sri Lanka was to announce the total military victory over the LTTE “Tamil Tiger” guerillas, a victory that came at a great cost to Sri Lankans of all ethnicities and traditions. After such a long period of conflict, may God grant that the “Venerable Island” return to peace, stability, and prosperity.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Andrew –

Thank you for yet another review of a parliament house. I must say that the new building is quite nice. Let us hope that true peace will descend on Sri Lanka.

Harold

PS: Happy St. Andrew’s Day.

I second the sentiment. Sri Lanka is one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever visited. I have fond memories of the train ride from Colombo to Kandy, through a magical jungle/mountain landscape, and an afternoon spent at the glorious Temple of the Tooth and a stroll around Kandy Lake.