2009 June

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Nature diary

by ‘REDSHANK’

St John’s Day, Midsummer Day, has come and gone, bringing to the nature diarists’ community, as the country folk call us, melancholy thoughts of the inexpugnable passage of time and of the already declining year. In our neighbourhood, St John’s Eve is a time when age-old customs, elsewhere, alas, confined to the mists of antiquity, still flourish even in these prosaic days.

Young men and maidens, not to speak of some in neither category, forsake their clubbing to dance in the woodland glades, undeterred by ghostly commercial travellers, doomed to play solo whist among the trees for all eternity, who scarcely interrupt their play to hurl traditional insults from another world.

Young men and maidens, not to speak of some in neither category, forsake their clubbing to dance in the woodland glades, undeterred by ghostly commercial travellers, doomed to play solo whist among the trees for all eternity, who scarcely interrupt their play to hurl traditional insults from another world.

It is different with the watercolourists who, following another ancient custom, come trooping out from the neighbouring town to set up their easels in the woods, industriously sketching everything they see, including the indignant dancers. Many of them are retired schoolteachers recommended “remedial art therapy” by their psychiatrists, distressed gentlefolk and ordinary people lately released into the community.

All take their orders from the big, ginger-haired old fellow who seems to be their leader. From my library window I watched through powerful field glasses as he rallied them amidst the dancers, lashing out with outsize paintbrush or sharp-edged paintbox and generally giving as good as they got.

He encouraged them, too, with anecdotes of eminent painters he seems to have known well: how he and Turner saw off a gang of criminal art dealers in Petworth Park; how he and Edward Lear, attacked by bandits while painting in Albania, put them to flight by endlessly repeating Lear’s limericks.

The village folk regard him with superstitious awe. He lives, so the talk goes in the Blacksmith’s Arms, in a rambling old mansion “way out t’ other side o’ Simpleham Great Park”. He is said to be a “gurt old ‘un for t’ book learnin’.” Some say he is writing a “Book of All Known Knowledge”. Some say he is the king of all nature diarists. All believe he is a powerful enchanter.

When I called at the inn the other day, there was an animated discussion about him, carried on, of course, in the genuine old British Composite Pandialect. Jack, the retired poacher told how, when laying a trail of sultanas to trap pheasants, he had seen the big man sitting in his enchanted garden, where creatures of the wild, deemed to be extinct in other parts of England, came to his call: the speckled linnet, the ringed dotterel, the corncrake and the wolf. Jack swore he had once seen an Andean condor perching on the enchanter’s shoulder and whispering secrets in his ear.

Old Frank the waspkeeper, who has a tendency to live in the past, and contributes a “Wasp at War” feature to the local newspaper, thinks the master watercolourist is a German or even Japanese spy, using watercolours to signal to enemy airmen. All believe he and his watercolourists are creatures of ill omen, and that to speak to them brings misfortune.

Though I am inclined to smile, I am sure there is a profound rural wisdom here, far beyond the grasp of your average know-all urban intellectual.

A Good Day in Cape Town

The South African Royal Family’s 1947 visit to “Die Moederstad”

SOUTH AFRICA IS a nation that took a long time birthing, from the first steps van Riebeeck took on the sands of Table Bay in 1652, through the tumult of the native wars, the tremendous conflict between Briton & Boer, and ultimately what was hoped would be the final reconciliation in Union of South Africa — 1910. In that year, young Prince Albert of York & of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was just fifteen years of age, and South Africa became a dominion just weeks after his father became King George V.

Albert was the second son of a second son, so at the time of his birth (and for most of his early life) it was never expected that he would one day be King of Great Britain, Emperor of India. It was his brother’s abdication that thrust poor Bertie, as he was always known to his loved ones, upon the throne imperial. It was a cold December day in 1936 that the heralds of the Court of St. James proclaimed him George VI.

By his nature, the King was a quiet and reserved man, partly because of the stammer that impeded his speech. George VI was happiest among his family, and they accompanied him in 1947 on a long voyage aboard HMS Vanguard, to his far-off kingdom on the other side of the world, where the two oceans meet. It was the first time a reigning monarch has set foot on South African soil, and Capetonians waited in earnest anticipation to see their sovereign. How appropriate that this happy city — moederstad, or “mother-city”, of all South Africa — would be the first to receive him. (more…)

Of poets & cheese

FOR G. K CHESTERTON to claim that poets have been “silent” on the subject of cheese is not quite accurate, as, while they have by no means been particularly vocal, one does occasionally stumble upon cheesely verse. I only cite one such example from The Farmer’s Boy of Robert Bloomfield (n. 1766, m. 1823).

Begins their work, begins the simple lay ;

The full-charged udder yields its willing streams,

While Mary sings some lover’s amorous dreams ;

And crouching Giles beneath a neighbouring tree

Tugs o’er his pail, and chants with equal glee.

Whose hat with tatter’d brim, of nap so bare,

From the cow’s side purloins a coat of hair,

A mottled ensign of his harmless trade,

An unambitious, peaceable cockade.

As unambitious too that cheerful aid

The mistress yields beside her rosy maid ;

With joy she views her plenteous reeking store,

And bears a brimmer to the dairy door ;

Her cows dissmiss’d, the luscious mead to roam,

Till eve again recall them loaded home,

And now the Dairy claims her choicest care,

And half her household find employment there ;

Slow rolls the churn, its load of clogging cream

At once forgoes its quality and name ;

From knotty particles first floating wide

Congealing butter’s dash’d from side to side ;

Streams of new milk through flowing coolers stray,

And snow-white curd abounds, and wholesome whey.

Due north th’ unglazed windows, cold and clear,

For warming sunbeams are unwelcome here.

Brisk goes the work beneath each busy hand,

And Giles must trudge, whoever gives command ;

A Gibeonite, that serves them all by turns ;

He drains the pump, from him the faggot burns ;

From him the noisy hogs demand their food ;

While at his heels run many a chirping brood,

Or down his path in expectation stand,

With equal claims upon his strewing hand.

Thus wastes the morn, till each with pleasure sees

The bustle o’er, and press’d the new-made cheese.

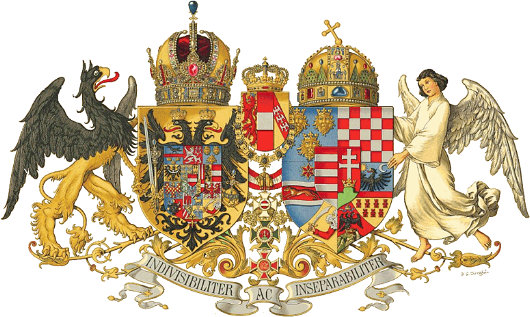

The Young Emperor

A reader notes in correspondence that Franz Joseph was not always old — though the popular conception certainly is of the Emperor in his later years. Here is the young Franz Joseph (or Ferenc József), just five years after he became Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, Bohemia, &c. The Emperor became so at such a young age because his father, Ferdinand I, abdicated after the revolts of 1848.

This portrait is by the Hungarian painter Miklós Barabás, who also completed portraits of the composer Franz Liszt, the novelist Baron József Eötvös de Vásárosnamény, William Tierney Clark, the Bristol engineer responsible for Budapest’s famous Chain Bridge, and many, many others.

The Goerke House, Lüderitz

THE FAMILIAR PHRASE has a person in difficult circumstances being “between a rock and a hard place”. The Namibian town of Lüderitz is stuck between the dry sands of the desert and salt water of the South Atlantic — this is the only country whose drinking water is 100% recycled. Life in this almost-pleasant German colonial outpost on the most inhospitable coast in the world has always been something of a difficulty, but the allure of diamonds has at least made it profitable. One such adventurer who came from afar and made his fortune in this outer limit of the Teutonic domains was one Hans Goerke. (more…)

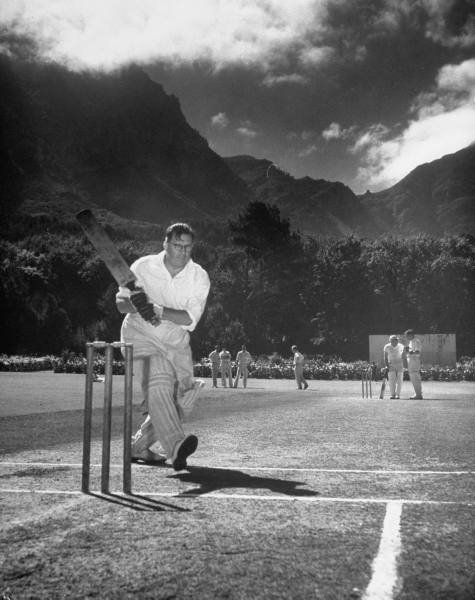

Minister van krieket

The Minister of the Interior, Mr. Theophilus Ebenhaezer Dönges, practises his swing while playing for the National Party cricket team.

Just a brief missive to note that the entry below is Post No. 1,000 on andrewcusack.com, and that this month just ending marks the completion of the fifth year of this little corner of the web.

The Huguenot Monument, Franschhoek

AMONG THE MANY peoples who, through the various vicissitudes of history, have found their home in South Africa are the Huguenots, or French Protestants. These people have always had a certain fascination for me, having being born so close to New Rochelle, the city in the New World founded by Huguenot refugees. The city’s public high school is a rather stately French neo-gothic chateau in the middle of Huguenot Park.

My own alma mater — a smaller private school in New Rochelle — counted Huguenot descendants among its first students and there was at least one remaining in my own school days. Street names such as Flandreau, Faneuil, and Coligni betray the French heritage of the city’s founders, and Trinity Church still has the old communion table brought over from La Rochelle. (more…)

The Saxon Palace, Warsaw

Unbenowst to me until recently, there are plans afoot to rebuild the Saxon Palace in Warsaw, though they have been — temporarily, I hope — suspended for lack of funds. The palace was almost totally destroyed in the Second World War (“The War Poland Lost Twice”), and the surviving part of the central arcade was turned into the Polish Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, now an obligatory stop for all foreign heads of state visiting the Polish capital.

The plan also provides for the neighbouring Brühl Palace to be rebuilt, to serve as the headquarters of the National Bank of Poland. Let’s hope they also decide to demolish that ugly modern monstrosity (to the right in the illustration above) that mars Piłsudski Square.

The eternal specter of the National Party

Above: Irish journalist Fergal Keane interviews a poor black South African.

This recent general election in South Africa marked the first time since 1910 — the year the country was unified as an independent dominion — that voters weren’t given the option of voting for the Nationalists. The party was founded in time for the 1914 election, and first entered government in coalition with the Labour party in 1924, but their most famous victory was in the general election of 1948. It was then that they won an outright majority and introduced the ideology of apartheid. The famous Brazilian counter-revolutionary Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira was of the opinion that South Africa had been in the process of developing a genuinely feudal society until the introduction of apartheid put a full-stop to this evolution.

Evil and heretical though apartheid was, such are the wounded and fearful hearts of men that it won for the National Party each successive general election until the introduction of universal suffrage in 1994. Admittedly, a large proportion of the Nationalist vote was not necessarily a vote for apartheid but instead a vote against communism. Soviet-backed communist subversion escalated sharply throughout Africa in the 1950s, especially as Nelson Mandela launched his internal coup taking over the previously broad-based & non-violent African National Congress and transforming that body into an officially and openly Soviet-aligned group with a terrorist wing whose activities rightly landed him in jail.

With the end of apartheid, the Nationalists had to contend with a universal adult electorate of every South African over eighteen years of age. In 1989, the last election under apartheid, over 2,000,000 whites, 261,000 coloureds (mixed-race people), and 154,000 Indians took advantage of their right to vote. In 1994, meanwhile, over 19.5 million voted. Most interestingly, the votes of the (mostly Afrikaans-speaking) coloured population — whose right to vote was taken away by the Nationalists in the 1950s before being quasi-reintroduced in 1984 — turned around and voted for the National Party en masse, out of fear for the behemoth of the black-dominated ANC.

The party still came second in the 1994 election with 20% of the vote — a respectable result considering the massive media push supporting Mandela & the ANC. But the National Party refused to take advantage of their showing. Under their supremely naïve leader, F. W. de Klerk, instead of forming a noticeable opposition to the ANC behemoth and thus laying the foundations for a robust tradition of antagonistic government and opposition debating eachother, the Nationalists did the worse thing imagineable and actually joined the government (as did the leaders of the black-conservative Inkatha Freedom Party). Had the Nationalists & Inkatha joined forces then as a united multi-racial moderate conservative opposition to the ANC, South Africa’s democracy would be in a much healthier state than it is today. Instead, they chose the gravy train and the voters have punished them in every subsequent election.

For their sins of opportunism, the Nationalists were rightly abandoned by voters and eventually the party dissolved itself and more-or-lessed merged into the ANC they had spent decades proclaiming the dangers of. Marthinus van Schalkwyk, the last leader of the Nationalists, is today an ANC member and cabinet minister. (Here I must concede that he is actually quite a capable minister and was a very sound conservationist as Minister for the Environment; his current portfolio is Tourism).

So April 2009 was the first general election since the dissolution of the National Party. F. W. de Klerk cast his vote in front of the news cameras and refused to divulge which of the parties got his vote, except that it was for an opposition party. Nonetheless, there were a number of eccentric parties which positioned themselves as new-born versions of the Nationalists. One, founded by a known charlatan and fraudster, actually claimed the name “National Party” and was quite multi-racial in its composition with a broadly populist agenda. Another, the “National Alliance“, was a primarily coloured group based in the Northern Cape. Both, however, used variants of the sun logo employed by the old Nationalists. How did they do? Well, rather predictably, convincing voters to back a party whose two best-known polices are first, apartheid, and second, sucking up to the ANC, was not an easy task. Both parties of a neo-Nat persuasion failed miserably, and I think it’s safe to say we’ll hear little of them again.

Still, the National Party’s forty-six straight years in power obviously impacted the history of this country, and their legacy lurks like a specter in the back of the minds of many. Eccentrics who try to resurrect this dead corpse, however, will swiftly be relegated to the cabinet of curiosities.

A new look for Argentina’s Herald

The Buenos Aires Herald is one of those newspapers that, by the grace of God, simply must continue existing no matter what horrors befall the newspaper industry as a whole. Finding up-to-date information on Argentina, in English, can be exceptionally frustrating and I had the Sunday version of the paper sent to me in New York every week; perfect reading for the train ride into work. Martin Gambarotta’s “Politics & Labour” column has to be one of the most informative and well-written political columns in any English-speaking newspaper. I also enjoyed the paid announcements section, informing readers of golf tournaments in aid of the Hospital Británico, meetings of the British-Argentine Chamber of Commerce, and when the next convocation of the South America Piping Association would be held. That said, when the Herald started denominating their subscription fee in dollars instead of pesos, I had to call it quits — though very reluctantly.

All the time while perusing the newspaper, however, I kept thinking “This could be better…”. Readers know how design-obsessed I am, especially when it comes to newspapers, and the Buenos Aires Herald would be such a better newspaper if they just tweaked a few things: a more judicious font choice, standardized white-spaces between columns, a few meliorations here and there. But now they’ve gone and redesigned the thing — without seeking the input of this devoted fan! — and they’ve got it all wrong. (more…)

The Queen at the Armory

Queen Elizabeth II & the Duke of Edinburgh attend a ball in their honour at the Seventh Regiment Armory in New York; October, 1957.

Praying with the Kaisers

by JOHN ZMIRAK

INSIDECATHOLIC.COM

As I’m writing this column at the tail end of my first trip to Vienna, some of you who’ve read me before might expect a bittersweet love note to the Habsburgs — a tear-stained column that splutters about Blessed Karl and “good Kaiser Franz Josef,” calls this a “pilgrimage” like my 2008 trip to the Vatican, and celebrates the dynasty that for centuries, with almost perfect consistency, upheld the material interests and political teachings of the Church, until by 1914 it was the only important government in the world on which the embattled Pope Pius X could rely for solid support. Then I’d rant for a while about how the Empire was purposely targeted by the messianic maniac Woodrow Wilson, whose Social Gospel was the prototype for the poison that drips today from the White House onto the dome of Notre Dame.

And you would be right. That’s exactly what I plan to say — so dyed-in-the-wool Americanists who regard the whole of the Catholic political past as a dark prelude to the blazing sun that was John Courtenay Murray (or John F. Kennedy) might as well close their eyes for the next 1,500 words — as they have to the past 1,500 years.

But as I bang that kettle drum again, I want to set two scenes, one from a fine and underrated movie, the other from my visit. The powerful historical drama “Sunshine” (1999) stars Ralph Fiennes as three successive members of a prosperous Jewish family in Habsburg Budapest. The film was so ambitious as to try portraying the broad sweep of historical change — and, as a result, it was not especially popular. What historical dramas we moderns tend to like are confined to the tale of a single hero, and how he wreaks vengeance on the villains with English accents who outraged the woman he loved. “Sunshine”, on the other hand, tells the vivid story of the degeneration of European civilization in the course of a mere 40 years. The Sonnenschein family are the witnesses, and the victims, as the creaky multinational monarchy ruled by the tolerant, devoutly Catholic Habsburgs gives way through reckless war to a series of political fanaticisms — all of them driven by some version of Collectivism, which the great Austrian Catholic political philosopher Erik von Kuenhelt-Leddihn calls “the ideology of the Herd.”

From a dynasty that claimed its legitimacy as the representative of divine authority at the apex of a great, interconnected pyramid of Being in which the lowliest Croatian fisherman (like my grandpa) had liberties guaranteed by the same Christian God who legitimated the Kaiser’s throne, Central Europe fell prey to one strain after another of groupthink under arms: From the Red Terror imposed by Hungarian Bolsheviks who loved only members of a given social class, to radical Hungarian nationalists who loved only conformist members of their tribe, to Nazi collaborationists who wouldn’t settle for assimilating Jews but wished to kill them, finally to Stalinist stooges who ended up reviving tribal anti-Semitism. The exhaustion at the film’s end is palpable: In the same amount of time that separates us today from President Lyndon Johnson, the peoples of Central Europe went from the kindly Kaiser Franz Josef through Adolf Hitler to Josef Stalin. Call it Progress.

Apart from a heavily bureaucratic empire that spun its wheels preventing its dozens of ethnic minorities from cleansing each other’s villages, what was lost with the fall of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy? For one thing, we lost the last political link Western Christendom had with the heritage of the Holy Roman Empire. (Its crown stands today in the Imperial Treasury at the Hofburg, and for me it’s a civic relic.) Charlemagne’s co-creation with the pope of his day, that Empire had symbolized a number of principles we could do well remembering today: Principally, the Empire (and the other Christian monarchies that once acknowledged its authority) represented the lay counterpart to the papacy, a tangible sign that the State’s authority came not from mere popular opinion, or the whims of tyrants, but an unchangeable order of Being, rooted in divine revelation and natural law.

The job of protecting the liberty of the Church and enforcing (yes, enforcing) that Law fell not to the clergy but to laymen. The clergy were not a political party or a pressure group — but a separate Estate that often as not served as a counterbalance to the authority of the monarchy. No monarch was absolute under this system, but held his rights in tension with the traditional privileges of nobles, clergy, the citizens of free towns, and serfs who were guaranteed the security of their land. Until the Reformation destroyed the Church’s power to resist the whims of kings — who suddenly had the option of pulling their nation out of communion with the pope — no king would have had the power or authority to rule with anything like the monarchical power of a U.S. president. Of course, no medieval monarch wielded 25-40 percent of his subjects’ wealth, or had the power to draft their children for foreign wars. It took the rise of democratic legal theory, as Hans Herman Hoppe has pointed out, to convince people that the State was really just an extension of themselves: a nice way to coax folks into allowing the State ever increasing dominance over their lives.

A Christian monarchy, whatever its flaws, was at least constrained in its abuses of power by certain fundamental principles of natural and canon law; when these were violated, as often they were, the abuse was clear to all, and the monarchy often suffered. In extreme cases, kings could be deposed. Today, by contrast, priests in Germany receive their salaries from the State, collected in taxes from citizens who check the “Catholic” box. So much for the independence of the clergy.

The House of Austria ruled the last regime in Europe that bound itself by such traditional strictures, which took for granted that its family and social policies must pass muster in the Vatican. By contrast, in the racially segregated America of 1914, eugenicists led by Margaret Sanger were already gearing up to impose mandatory sterilization in a dozen U.S. states (as they would succeed in doing by 1930), while Prohibitionist clergymen and Klansmen (they worked together on this) were getting ready to close all the bars. As historian Richard Gamble has written, in 1914 the United States was the most “progressive” and secular government in the world — and by 1918, it was one of the most conservative. We didn’t shift; the spectrum did.

Dismantled by angry nationalists who set up tiny and often intolerant regimes that couldn’t defend themselves, nearly every inch of Franz-Josef’s realm would fall first into the hands of Adolf Hitler, then those of Josef Stalin. Today, these realms are largely (not wholly) secularized, exhausted perhaps by the enervating and brutal history they have suffered, interested largely in the calm and meaningless comfort offered by modern capitalism, rendered safer and even duller by the buffer of socialist insurance. The peoples who once thrilled to the agonies and ecstasies carved into the stone churches here in Vienna can now barely rouse the energy to reproduce themselves. Make war? Making love seems barely worth the tussle or the nappies. Over in America, we’re equally in love with peace and comfort — although we’ve a slightly higher (market-driven?) tolerance for risk, and hence a higher birthrate. For the moment.

Speaking of children brings me to the most haunting image I will take away from Austria. I spent a whole afternoon exploring the most beautiful Catholic church I have ever seen — including those in Rome — the Steinhof, built by Jugendstil architect Otto Wagner and designed by Kolomon Moser. An exquisite balance of modern, almost Art-Deco elements with the classical traditions of church architecture, it seems to me clear evidence that we could have built reverent modern places of worship, ones that don’t simply ape the past. And we still can. A little too modern for Kaiser Franz, the place was funded, the kindly tour guide told me in broken English, by the Viennese bourgeoisie. (Since my family only recently clawed its way into that social class, I felt a little surge of pride.) Apart from the stunning sanctuary, the most impressive element in the church is the series of stained-glass windows depicting the seven Spiritual and the seven Corporal Works of Mercy — each with a saint who embodied a given work. All this was especially moving given the function of the Steinhof, which served and serves as the chapel of Vienna’s mental hospital. (It wasn’t so easy getting a tour!) The church was made exquisite, the guide explained, intentionally to remind the patients that their society hadn’t abandoned them. Moser does more than Sig Freud can to reconcile God’s ways to man.

We see in the chapel the spirit of Franz Josef’s Austria, the pre-modern mythos that grants man a sacred place in a universe where he was created a little lower than the angels — and an emperor stands only in a different spot, with heavier burdens facing a harsher judgment than his subjects. No wonder Franz Josef slept on a narrow cot in an apartment that wouldn’t pass muster on New York’s Park Avenue, rose at 4 a.m. to work, and granted an audience to any subject who requested it. He knew that he faced a Judge who isn’t impressed by crowns.

As we left the church, I asked the guide about a plaque I’d seen but couldn’t quite ken, and her face grew suddenly solemn. “That is the next part of the tour.” She explained to me and the group the purpose of the Spiegelgrund Memorial. It stands in the part of the hospital once reserved for what we’d call “exceptional children,” those with mental or physical handicaps. While Austria was a Christian monarchy, such children were taught to busy themselves with crafts and educated as widely as their handicaps permitted. The soul of each, as Franz Josef would freely have admitted, was equal to the emperor’s. But in 1939, Austria didn’t have an emperor anymore. It dwelt under the democratically elected, hugely popular leader of a regime that justly called itself “socialist.” The ethos that prevailed was a weird mix of romanticism and cold utilitarian calculation, one which shouldn’t be too unfamiliar to us. It worried about the suffering of lebensunwertes Leben, or “life unworthy of life”–a phrase we might as well revive in our democratic country that aborts 90 percent of Down’s Syndrome children diagnosed in utero. So the Spiegelgrund was transformed from a rehabilitation center to one that specialized in experimentation. As the Holocaust memorial site Nizkor documents:

In Nazi Austria, parents were encouraged to leave their disabled children in the care of people like [Spiegelgrund director] Dr. Heinrich Gross. If the youngsters had been born with defects, wet their beds, or were deemed unsociable, the neurobiologist killed them and removed their brains for examination. …

Children were killed because they stuttered, had a harelip, had eyes too far apart. They died by injection or were left outdoors to freeze or were simply starved.

Dr. Gross saved the children’s brains for “research” (not on stem cells, we must hope). All this, a few hundred feet from the windows depicting the Works of Mercy. Of course, they’d been replaced by the works of Modernity.

We’re much more civilized about this sort of thing nowadays, as the guests at Dr. George Tiller’s secular canonization can testify. In true American fashion, our genocide is libertarian and voluntarist, enacted for profit and covered by insurance.

I will think of the children of the Spiegelgrund tomorrow, as I spend the morning in the Kapuzinkirche, where the Habsburg emperors are buried — and the Fraternity of St. Peter say a daily Latin Mass. As I pray the canon my ancestors prayed and venerate the emperors they revered, I will beg the good Lord for some respite from all the Progress we’ve enjoyed.

Blessed Karl I, ora pro nobis.

[Dr. John Zmirak‘s column appears every week at InsideCatholic.com.]

The Order of Malta in Peru

A correspondent of this site sends these images of the Order of Malta in Peru. The Order of Malta has a long history in Peru: Manuel de Guirior, 1st Marqués de Guiror and a knight of the Order (right, baptised José Manuel de Guirior Portal de Huarte Herdozain y González de Sepúlveda) was Viceroy of Peru from 1776 to 1780, having previously served the King of Spain as Viceroy of New Granada.

A correspondent of this site sends these images of the Order of Malta in Peru. The Order of Malta has a long history in Peru: Manuel de Guirior, 1st Marqués de Guiror and a knight of the Order (right, baptised José Manuel de Guirior Portal de Huarte Herdozain y González de Sepúlveda) was Viceroy of Peru from 1776 to 1780, having previously served the King of Spain as Viceroy of New Granada.

More recently, in 2008, this investiture (above) was presided over by Fernando de Trazegnies, Marquis of Torrebermeja, the former Dean of Law at the Catholic University of Peru and now head of the Peruvian Association of the Order. The investiture took place in the eighteenth-century Church of the Magdalena, and the Mass was offered by the Cardinal Archbishop of Lima, Juan Luis Cipriani.

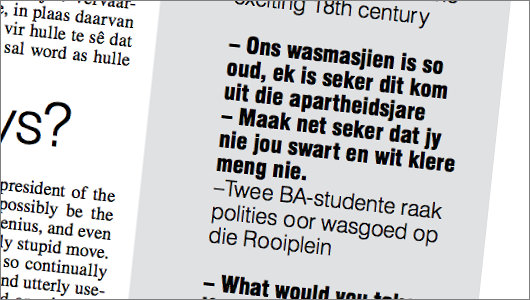

« Kampusquote »

Many college newspapers have their “overheard” sections, in which they give a selection of amusing or stupid things said around town. Our paper, Die Matie, has “Kampusquote”, the latest installment of which featured this nugget:

“Just make sure you don’t mix your white and black clothes!”

Alright, it sounds better in Afrikaans. Another favourite of mine was:

— Student upon learning that the head of the Music Conservatory is rotated amongst the conservatory’s departmental chairs

Argentina Mourns an Honest Man

RAÚL ALFONSÍN WAS often a stumbling, bumbling leader when he served as President of the Argentine Republic but, in a country of rampant corruption and abuse, his personal integrity was unassailable. It was probably for that reason that Argentines came on to the streets of Buenos Aires in April to mourn the loss of, certainly not the greatest statesman of the country’s history, but at least something simple: an honest man. For more on the late president, see my piece over at InsideCatholic.com. (more…)

The Dutch Flags of New York

The vexillological inheritance from our Netherlandic motherland

NEEDLESS TO SAY, New York owes a great deal to our Netherlandic founders, who imbued the city and land with much of its culture, eventually transformed (but not supplanted) by the overwhelming influence of the English who snuck a few warships into the harbour and knicked this land from the Hollanders. One of the many signs of New York’s Dutch history are the numerous flags which so obviously and proudly display this heritage. Here are just a few simple notes about a few of these flags.

Some reading notes

ROBERT O’BRIEN, IN a deliberately provocative gesture, once said in conversation that he pitied America for not having any literature. Preposterous! was my natural response. We have Chaucer and Shakespeare and Mallory and Dickens! Yes, you Britons have them too, but you will have to share, I’m afraid. To try to separate America from the English greats is the equivalent of forbidding a son from taking pride in his family’s long and illustrious history. He may not be the eldest male descendant, but does this mean he must deny his heritage? Of course not. Naturally, like the Scots and the Irish we have our own subset of English literature — Mark Twain, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Flannery O’Connor, and J.D. Salinger come to mind — and there are even a few crossovers such as Henry James and T.S. Eliot.

The idea of doing a degree in English or in any literature has always seemed unattractive to me, though I by no means advocate the abolition of English departments. Perhaps it’s because I rarely found English a compelling subject in high school, though I did have some extremely talented teachers: The P (as she is known), as well as Mr. Leahy. I am one of those no doubt millions who wishes he had actually read all those books he supposedly read for class at school. I did enjoy Sophocles, and Homer too, but I did not really get into Flaubert (I intend to revisit him). Crime and Punishment I soaked up at the time, but have since forgotten.

How tiresome it must be, as a formal student of literature, to be forced to answer questions about works you have read. I wonder if there should be two tracks within universities: one for gentlemen, who merely seek to learn, and another for budding academics, who need proof they’ve learnt something. Some books have taken years (and multiple readings) to truly sink in, so it seems preposterous to arbitrarily require a succinct series of answers to examination questions at the end of a term.

Idea-driven novels seem foolish to me as well. In New York, I knew a Frenchman, not much older than myself, who (I discovered) was in the midst of writing a novel. Intrigued, I asked him one day what the novel is about. He paused for a few moments, sat back, and slowly tapped his finger thrice on the table in thought, and said “Stratification”. Well! Call me a simpleton but I would have preferred “a guy, a girl, a plot, an affair, schoolmates, a day, a week . . .” anything, but “stratification”?

Well, he is writing in French, and if you are going to write an idea-driven novel, it’s probably best to do it in French.

What have I been reading lately? A few months ago I finished Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands — an absolutely cracking book. It was late in the African summer, and I was perched appropriately on the sands of Kogelbaai — one of the most stunning beaches in the Cape. What’s more, it was a weekday afternoon, and so the strand was abandoned but for our small party, so we sat, read, napped, explored the rocks, and enjoyed the beauty of our surrounds. Another cracking read was Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday. The author subtitled his book “A Nightmare” and it had moments of utter fear and dread, but also, being Chesterton, moments of ridiculous farce and hilarity: a fascinating insight into the mind and mentality of a jovial and saintly man.

H.V. Morton, the man who convinced me to come to South Africa with his In Search of South Africa, showed me the Eternal City with A Traveller in Rome, and I am so tantalizingly close to finishing that magnificent work of Thomas Pakenham (now Lord Longford, since the death of his father), The Boer War. Pakenham is an historian beyond compare. I began Kristin Lavransdatter to great enjoyment, but am waiting till my return to New York to complete it. I started The Prisoner of Zenda while travelling in Namibia and finished it on Pentecost weekend. Boswell’s Johnson I found an excellent little india-paper edition of in a tiny back-alley shop in Wells last year (we ran into Michael Alexander on the street) and I’ve been pottering through it bit-by-bit. On the recommendation of Stefan Beck I picked up J.P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man but found it obsessively vulgar and, worse, boring, so returned it to the goodly people at the Universiteit se biblioteek.

I still have out from the library a handsome, handy, small German printing of Legends of the Rhine (translated into English). I like small books, books you can easily fit in the pocket of a field coat and whip out at a moment’s notice. At a reception in a New York gallery some time ago, I learned from John Derbyshire that the determining factor of the old Penguins’ size was that it would fit in the front coat pocket of a British Army officer. The new size of Penguins are much too large to carry about as emergency reading, which makes me very glad that they’ve brought back the older, smaller size.

Penguins aside, I still prefer those shorter, fatter editions printed on thinnest india-paper. Jocelyn, my cook at university, gave me such a copy of The Pickwick Papers (inscribed “To Andrew Cusack — one of the most Pickwickian individuals I have ever met”) for my birthday one year, and it is one of the dearest editions I own. Does anyone print on india-paper anymore? I suspect not, and more’s the pity. Michael Wharton (better known as Peter Simple) noted shortly before his death how difficult it was becoming to obtain sheets of foolscap in London. Thus passes the glories of the world…

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories