2009 March

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

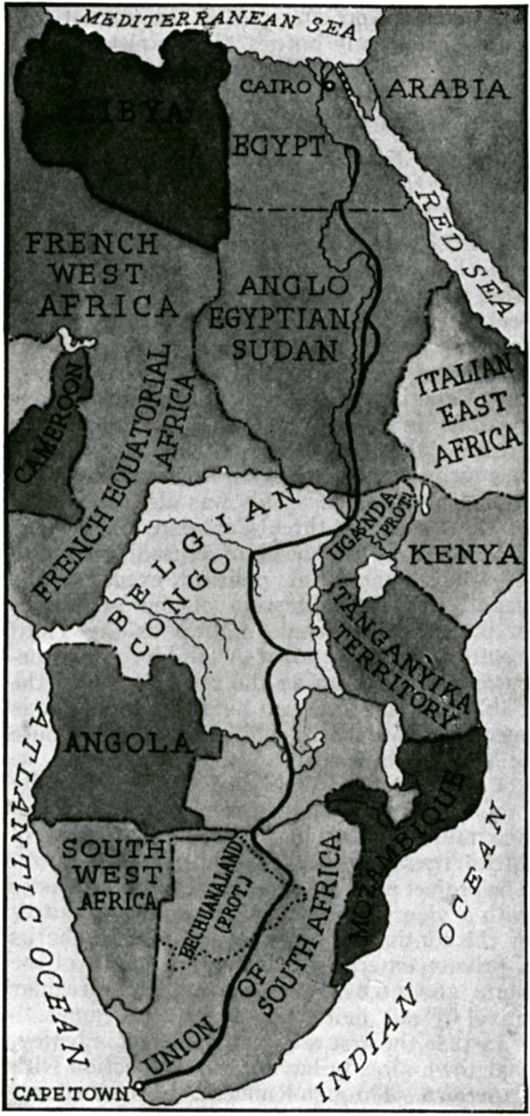

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Paul Comtois of Québec

Farmer, Politician, Hero, Saint

FROM TIME TO TIME there are men in history whose heroism runs so counter to the spirit of the age that the arbiters of passing fashion must simply ignore him rather than run the risk of acknowledging his embarrassing greatness and goodness. God has graced the New World with many of His saints, some of whom — Rose of Lima, Martin de Porres, Mother Seton — have already been raised to the altar, others — Fulton Sheen, Fr. Solanus Casey — are certainly on their way. Yet more remain unsung and almost forgotten: Paul Comtois (1895–1966), Lieutenant-Governor of Québec until his heroic death, is just one of these saints.

Count von Stauffenberg: “We Live in a Society of Lemmings”

Count Franz Ludwig von Stauffenberg, the third son of Hitler’s would-be assassin Count Claus von Stauffenberg and brother to Gen. Berthold von Stauffenberg, recently spoke to the German magazine FOCUS about Germany’s ratification of the Lisbon Treaty. Stauffenberg, a father of four and grandfather of eight, has spent his life as an attorney and a politician for the Bavarian Christian Social Union party, serving in the Bundestag from 1976 to 1987 and as a Member of the European Parliament from 1984 to 1992.

FOCUS asked the Count about his participation in the German court challenge against the Lisbon Treaty.

“I see the way to [the Constitutional Court] as a last resort,” the Count said, “and had hoped that we could compel a re-think through an ordinary democratic manner, through argument, debate, and public pressure. This has totally failed. I’m not anti-European; I was long enough a CSU Member of the European Parliament. This Europe is no longer compatible with the basic structures of a democratic legal state.”

FOCUS: Has your case something to do with your experience as the son of the resistance fighter Count von Stauffenberg?

“No. My father expected that his children would … stand on their own as a man or woman. I didn’t go into politics from devout worship of my father, but because of the unsuccessful paths of my peers from the generation of 1968.”

FOCUS: Your action comes late. Why have you waited so long?

“In Brussels, there was no sudden seizure of power, but a systematic, persistent development, in which the Bundestag deputies, constantly obedient and even docile, incapacitated themselves. They see themselves as a reserve team for higher office rather than in their actual role as inspectors to reflect, as a counter force on equal footing.”

FOCUS: How can it be that so few see a risk in the Lisbon Treaty, and the rest should be so beaten with blindness?

“In Germany, almost no one wanted to hear concerns. We live in a society of lemmings.”

Link: Graf Stauffenberg: “Wir leben in einer Gesellschaft von Lemmingen” (In German)

A new bookplate for the NYG&B

Fr. Guy Selvester reports on his resurrected Shouts in the Piazza blog that the great Marco Foppoli has designed a new bookplate for the New York Genealogical & Biographical Society. Mr. Foppoli is the most highly-regarded heraldic artist of our day, and the influence of the style of his mentor, the late Archbishop Bruno Heim, is apparent in his work.

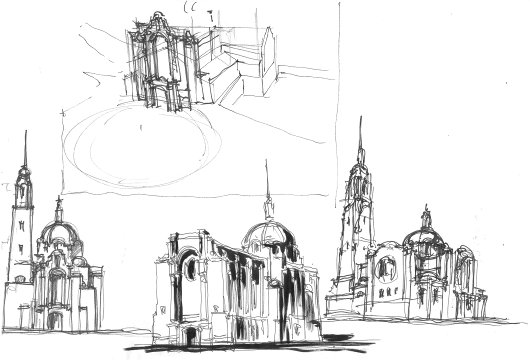

Matt Alderman’s at it again

The king of counter-proposals sets eyes on Divine Mercy shrine

Young architect Matt Alderman presents his counter-proposal to a horrifyingly kitsch proposal for a West-Coast U.S. shrine to the Divine Mercy. Why, given that the recovery of skill & talent in architecture in the past few decades, are most new churches still revoltingly ugly? “The problem is not that it is hard to get beautiful churches built, but that the wrong people seem to end up getting the commissions,” Matt writes. “Oakland and Los Angeles were, of course, going to go modernistic no matter what, but Houston Cathedral could have been a masterpiece if handled by someone with a greater openness to traditional design, rather than settling for a mediocre pseudo-traditionalism.”

Happy St. Patrick’s Day

Another view of Dublin’s splendid General Post Office on O’Connell Street; the last one we posted was from half a century earlier.

The Grand Master in Hungary

His Most Eminent Highness, Fra’ Matthew Festing, the Prince & Grand Master of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta made a four-day visit to Hungary last month, from 8-11 of February. The Grand Master was invited to Hungary by the President of the Republic, Mr. László Sólyom, who met with Fra’ Matthew at the Sándor Palace in Budapest. The President and the Grand Master discussed the various collaborative efforts between Hungary and the Order of Malta in health and social fields and discussed the possibility of further developing those projects.

A Sunday Afternoon in Buenos Aires

A sidewalk café on a Sunday afternoon, Buenos Aires, 1964.

Eric Seddon on Washington Irving

Alongside Miklos Banffy, Washington Irving is probably my favourite author. I have two sets of his complete works, and will obtain at least a third — my favourite printing of the complete Irving, in an excellent handy size — when I can find it for the right price. It is curious, but by no means suprising, that Irving’s genius is nearly forgotten today even though he was the first American to be an international superstar, famed on both sides of the Atlantic. He is mostly known only through his authorship of Rip van Winkel and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, both of which works are rarely presented in their original written form, but almost always in shortened illustrated versions for schoolchildren from publishers convinced of their audience’s stupidity.

Irving is rarely in the limelight these days, but First Things Online recently published an informative article, “Washington Irving and the Specter of Cultural Continuity” by one Eric Seddon, that is well worth reading.

His first book, Dietrich Knickerbocker’s History of New York, capitalized on the amnesia of New Yorkers by a mix of biting satire and real history of the Dutch reign in Manhattan. The book is foundational to any study in American humor. It is wild, free, self-deprecatory, and merciless to the public figures of his day, and by turns lyrically funny, absurd, and reflective. Without it, we might wonder whether American humor, from Twain to the Marx brothers to Seinfeld, would have taken the particular shape it did.

When Americans, always prone to utopian daydreams, were in danger of taking themselves far too seriously, when the term “manifest destiny” was embryonic, Dietrich Knickerbocker rolled his bugged-out eyes, chuckled gruffly, and whispered into the ear of a young nation, “Remember thou art mortal.” […]

Irving’s two most famous stories are to be found in The Sketch Book, virtually bookending the text: “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” In “Rip Van Winkle,” Irving whimsically pointed out the hazards of the new Republic, that a once humble acceptance of life under monarchy could easily give way to arrogant corruption, vice, and the nauseating specter of being governed by village idiots with a gift for demagoguery. […]

The final warning of the book comes in the form of a Headless Horseman, who is either a real ghost of the Revolution or the town bully in disguise, and who targets, of all people, the schoolmaster (even small towns have their intelligentsia). Is it history chasing Icabod Crane, the puritanical teacher obsessed with stories of witch hunts, or just Brom Bones scaring him out of town? Irving doesn’t say, and perhaps our answers tell more about ourselves than about him.

Washington Irving spent his last days in Tarrytown, near the setting of his most famous story. He was a member of the local Episcopal Church, tried to revive the old Dutch festivities on St. Nicholas Day, and was moved to tears by singing the Gloria. In particular he loved to repeat the words “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, and good-will to men.” Though his era was in many ways a bigoted one, he resisted and thereby helped to shape a better future. One of his last revisions to Knickerbocker came late, removing the anti-Catholic references its youthful version contained. He was a man who had seen his share of specters, to be sure, but who didn’t believe they were the strongest reality.

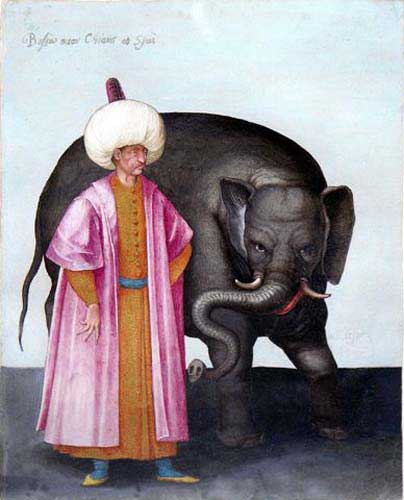

A Turbaned Pasha with an Elephant

Tempera and shell gold on paper, 10.0 in. x 8.8 in.

c. 1580-1585, Private collection (now for sale)

While known as a painter of large-scale works, a draftsman, and a printmaker, Jacopo Ligozzi — the court painter to the Grand Dukes Francesco I, Ferdinando I, Cosimo II, and Ferdinando II — also completed a series of drawings depicting Turkish traditional dress and costume. Interest in the Ottoman empire and its people increased after the great victory over the Turks at Lepanto in 1571, commemorated as a Christian feast to this day. Ligozzi never visited the Turkish realm himself but derived his inspiration for this particular illustration from the drawings accompanying the Venetian edition of Nicolas de Nicolay’s chronicle of the 1551 embassy of Henri II to the court of Suleyman the Magnificent.

That, at any rate, is the source of the Pasha; the inspiration for the elephant (of the African variety) remains undetermined. Suleyman gave an African elephant accompanied by a turbaned mahout and a staff of thirty to the future Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II, and it’s probable that Ligozzi used a printed depiction of this as a source for the picture here. (Earlier, in 1514, the King of Portugal gave an elephant named Hanno to Pope Leo X, a Medici).

This charming work, available from the Arader gallery of New York, is one from the series of tempera depictions of Turkish costume by Ligozzi, twenty of which are in the Uffizi, one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and another in the Getty Museum of Los Angeles. It was probably painted between 1580 and 1585 while the artist was in the service of Grand Duke Francesco I de Medici. Ligozzi’s depictions were first bound in a single volume in the possession of the Gaddi family before, in 1740, the manuscript reached the hands of the Manifattura Ginori de Doccia, the porcelain factory founded outside Florence in 1735 by Marchese Carlo Ginori. There, it inspired a number of porcelain platters which are today dispersed around collections worldwide. The principal group of these illustrations were donated to the Uffizi in 1867.

Un soupçon de couleur

These two numbers of the Gaullist newspaper Le Rassemblement show what even a little dose of colour can do for a journal printed in black-and-white. The lack of additional colour was due to economical, not to mention technological, restraints, but we have now gotten well used to our newspapers being printed in a full array of colour. Yes, even the FAZ.

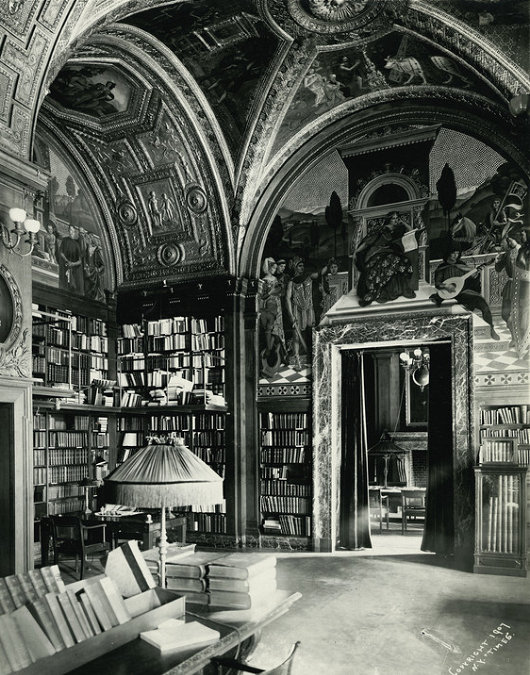

The Finest Library in All New York

Or is it in all the New World?

I do miss my two libraries in Manhattan, the Society Library on 79th Street and the Haskell Library at the French Institute on 60th. Neither of them, however, are fit to shine the boots of the library of the University Club on 54th & Fifth. Architecturally and artistically, it is undoubtedly the finest library in New York. But does it have an equal or a better in all the New World? The BN in BA certainly isn’t a competitor.

Old Radders

The devil in me, while entirely appreciative of the beauty of Radcliffe Camera, sometimes wonders if the handsome square it is in might be better off without it. What would it look like?

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories