2007 March

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Breaking the Mold in Quebec

WAS I THE only one south of the border who was glued to the computer screen watching CBC TV’s streaming online coverage of the Quebec elections? The results of the vote for the provincial parliament proved surprisingly exciting, perhaps even dramatic. The star of the evening was the stunning success of Mario Dumont’s Action Democratique du Quebec, breaking out of their small strongholds and winning seats across the entire province. They even made inroads in the leftist bastion of Montreal. While they did not win any seats on the island of Montreal, the came second in a number of ridings (as constituencies are known in Canada), and took a number of seats in the Montreal suburbs. But perhaps I should give a little background to what’s going on. (more…)

Nuns! Nuns! Nuns!

This brief piece from NBC has been making the rounds on a number of blogs, but I thought I’d share it for those folks who haven’t caught it yet.

Attack of the Killer Poets

The gentlefolks’ aortas will gush without me.

The last chance to get stained with blood

I let go by.

Ever more often I answer ancient calls

And watch the mountains turn green.

Aeschylus fought at Marathon, Maecenas rode with Octavian, and even Coleridge had a spell in the Dragoons (under the assumed name of Silas Tomkyn Combebach), yet more recent examples of convergence between the realms of the poetical and the military leave something to be desired. The above quotation is a mere snippet from the works of Radovan Karadžić, sometime leader of the Bosnian Serb forces during the disintegration of Yugoslavia. As a Hungarian friend said recently, “If that doesn’t get him sent to the Hague, I don’t know what will!”

Misery loving company, Karadzic invited Eduard Limonov, the Russian poet, writer, and all-around nasty character, to Bosnia in the midst of the Seige of Sarajevo. This brief YouTube clip shows the two poets inspecting a Serb position overlooking the town. The tousled-haired Karadzic gloats over the woebegone metropolis while Limonov takes aim at a few civilians through the sight of a sniper rifle before opening fire. (Limonov returned to Mother Russia, where he founded the National Bolshevik, or “Nazbol” party. Is there no Russian Wodehouse to ridicule this strange band of neo-Hitlerite Stalin-worshippers? “Spagbol” seems an obvious equivalent of Roderick Spode’s Black Shorts.)

Meanwhile, we read in the feuilleton of today’s Süddeutsche Zeitung (via signandsight.com) that German authorities have refused to grant asylum to the Chechen poet Apti Bisultanov. Bisultanov, as it turns out, led a unit of thirty-five men during the Battle of Grozny and has been accused of a number of war crimes and human rights violations.

Kinda makes you wonder what nefarious plots are being hatched when David Yezzi meets Ben Downing for a drink at the Old Town.

[Cross-posted at Armavirumque]

Hail Glorious Saint Patrick

THE FEAST OF IRELAND’S patron saint is an occasion for parading if ever there was one. For this, we can send part of our thanks to the British Army, which happened to initiate the most famous St. Patrick’s Day Parade of them all, namely, New York’s. It was 1762 when a number of Irish troops in the service of the Crown took it upon themselves to parade up Gotham’s own Broadway on the 17th of March. (More recently, the Duke of Edinburgh was invited to partake in the New York parade during his 1966 visit to America). Despite the lamentable outbreak of separatist republicanism in much of Ireland, the sons of Erin continue to take the Queen’s shilling and serve proudly in Her Majesty’s forces, and true to form they are sure to mark their patron’s feast day.

‘Titus’

JULIE TAYMOR’S VERSION of Shakespeare’s “Titus Andronicus”, the 1999 film “Titus” (with Anthony Hopkins in the title role), is a rather interesting modern interpretation. It has rather whimsical aspects, such as the ‘SPQR News’ microphone the characters are seen speaking into. The rivals for the imperial throne bedeck their supporters in the colors of Rome’s rival football teams: the red and yellow of Roma for Saturninus and the pale blue and white of Lazio for Bassianus. I especially enjoy the Senators bedecked in old-school white suits making them appear like a convivium of Kentucky colonels. Worth seeing.

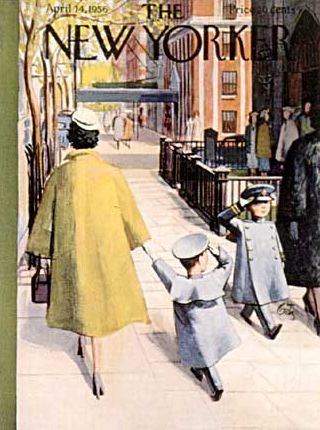

The Knickerbocker Greys

The Knickerbocker Greys, the Upper East Side corps of cadets, is celebrating its 125th year in existence. Both the Times and the Sun have featured articles on the Greys:

‘Celebrating 125 With the Knickerbocker Greys‘ by Gary Shapiro (The New York Sun)

‘Manhattan’s Littlest Soldiers‘ by Eric Königsberg (The New York Times)

Above: A mother mends a cadet’s uniform.

Below: Cadets assembled in an Armory corridor. (Note the interior scaffolding due to the State’s grievous neglect of the Armory).

The ‘CNN Effect’

A number of International Relations students at St Andrews have created this video (5:18) illustrating what is known in that field of study as the ‘CNN effect‘ on a crisis in fictional ‘Berniestan’.

Lord Glenavy

Sir James Henry Mussen Campbell, Bt., 1st Baron Glenavy, PC, QC. was born in Dublin in 1851. Campbell graduated from the University of Dublin (Trinity College) a Bachelor of the Arts in 1874. He was called to the Irish bar in 1878, being made a Queen’s Counsel in 1892.

Campbell was elected to Parliament in 1898, being called to the English bar a year later. He was made Solicitor General for Ireland in 1903, as well as being appointed an Irish Privy Counsellor. He rose to become Lord Chief Justice of Ireland in 1916, being made a baronet the following year, and Lord Chancellor of Ireland the year after that (1918). Sir James was ennobled as 1st Baron Glenavy upon relinquishing office in 1921.

Ireland was partitioned in the following year, and Lord Glenavy became the first Cathaoirleach of Seanad Éireann (Presiding officer of the Irish senate). In 1923, he chaired the judicial committee investigating the establishment of a new courts system for the Irish Free State. His proposals were implemented the following year in the Courts of Justice Act 1924, forming the Irish courts as they remain today.

Having served one six-year term in the Seanad, he did not seek re-election in 1928, and died three years later in 1931. Holding the largely honorary position of President of the College Historical Society (“the Hist”), Dublin University’s debating society, from 1925, he was succeeded upon his death by his fellow Irish Protestant, Douglas Hyde, who himself later became the first President of Ireland from 1938 until 1945.

Diary

THE RECENT UTTERANCE of most grievous blasphemies against the Holy Spirit and the Blessed Virgin by a member of Senator John Edwards’ presidential campaign team sparked great scandal, much compounded by the Senator standing by the offending party after the affair erupted. While she has since resigned, one wonders in what jurisdiction her comments, posted electronically on the internet, were made. Blasphemy remains a common law offense in New York, while one suspects it is almost as rarely enforced as those as-yet-unrepealed Plantagenet-era laws requiring all free-born Englishmen to practice archery weekly.

The blasphemy case which obtained the greatest reknown in these parts took place in December of 1810. A man (we will not call him gentle) by the name of Timothy Ruggles was brought to court in Salem in Charlotte County, New York. (Or, more properly, Washington County, as that particular bailiwick, originally named after the patron of the arts and Queen Consort to King George the Last, had been rechristened after a George of more recent popularity). Ruggles, anyhow, had made grievously blasphemous utterances against Our Lord and the Blessed Virgin which do not bear repeating (but which the inquisitive and hard-stomached scholar can find in the appropriate academic sources).

Ruggles had reckoned himself a “free thinker” and the townsfolk made haste to ensure he would be, at the very least, an imprisoned one. Found guilty in the Court of Oyer and Terminer of Salem, he was jailed for three months and fined $500. The blasphemer appealed the conviction, his lawyer arguing that there was no specific statute against blasphemy in the State of New York. The great James Kent, Chief Justice (and later Chancellor) of New York whose Commentaries on American Law earned him the worthy cognomen of “America’s Blackstone”, however, upheld the blasphemy conviction, citing blasphemy as a threat to morality and public welfare and “offence against the public peace and safety”. Would that such was the case today!

IN THE MIDST of the frigid cold, I found myself (a fortnight ago) having a meander around the old Ward estate in New Rochelle. I was very glad that I had brought my walking stick along, as most of the old paths were covered in frozen snow. Without the aid of it, I most certainly would have slipped and cracked my head. A good few nooks and gullies had filled with frozen snow and water, to the extent that some small trees were eerily half-submerged in white. In a clearing amidst the barren trees, the old house sits, boarded-up and somewhat neglected. Despite being surrounded by sheets of ice, I circumnavigated it, and gave as good an inspection as I could before the cold bade me onwards, and back home.

Just as I reached the edge of the estate by the old forge, I came upon an old man with a giant of a beast that may very well have been the Hound of Cullen. My presence was acknowledge by a great loud bark, one of such ambiguity as to leave me guessing whether it was of welcome or suspicion. The old man promptly leashed the enormous beast. “No good out there today,” he said. “Expect it’s all frozen over”. “Yes, quite,” I tersely responded, my mind still arrested by the Hound of Cullen. (The reader will recall that only the week before, my right calf had been the object of a terrier’s affections). “Better in a few weeks,” the Old Man said in aspiration. “Hope so”. Realizing my own terseness, I expressed my wish that the Old Man and the Hound of Cullen enjoy the remainder of the afternoon, and, the wish having been returned in kind, I proceeded home to the warmth of my own abode.

RATHER APPROPRIATELY, the landlord of our pub has been appointed Grand Marshal of the town’s St. Patrick’s Parade, which will duly be held tommorrow. Monsignor Doyle even appeared before mass last Sunday to solemnly announce the honor to the assembled faithful, citing this public citizen’s good works (among them, sending food over from his rather capable kitchens when the rectory cook is away).

I recall, with fondness, Mr. Fogarty’s ardent protests (consisting primarily of a shaked fist and some strongly-pronounced verbiage) when the village police, in a fit of overzealousness, erected checkpoints at every neighboring intersection to the pub, stopping every single passing automobile and “breathalyzing” the driver thereof. Needless to say, many a car was left on the village streets that night, including that of yours truly. Irritatingly, it was already winter, and I had to make the uphill walk home in the cold. Also, while traversing the hockey field behind the school, I was forced to climb over a fence in order to evade a skunk. We were not impressed by the village police that night, and heartily concurred with Mr. Fogarty’s protests. No doubt he will do a good job of waving to the assembled Gaelry, compulsively bedecked in the Arran jumper and ceremonial sash which are typical of St. Patrick’s Day Parade Grand Marshals past and present.

Does this position confer, we wonder, a certain suzerainity over the town’s Irish-Americans?

THIS EVENING WAS SPENT, happily, in front of the fire, perusing the Encyclopedia of New York State given to me by Col. & Mrs. Cusack, my aunt and uncle next door. It is a worthy companion to the equally weighty Encyclopedia of New York City (an updated edition of which will appear next year). Between stoking the flames and letting the dog in and out of the house, I learnt about agriculture in Westchester (over 2,000 farms in 1850 but only 91 today), almshouses, art collecting, Austerlitz (pop. 1,453), aviation, bagel production, the Bahá’í faith (“white Protestants remain the principal source of converts”), and Ballston Spa.

PERHAPS I WILL go wander around the old Ward estate again when I return from the city tommorrow. The ice will surely have melted by now, but then tonight’s rains might turn it a bit muddy. On the other hand, I’ve only gotten as far as Ballston Spa in my latest perusal of the Encyclopedia. Very well, I intend to do both (and will likely end up doing neither).

The Revolting Parade

BEING, AS WE are, in the midst of the presidential campaign pre-season, the press have been exploring the various candidates for the highest office in the land. It is a revolting parade of the sordid, the inane, the insane, the monomaniacal, and the self-obsessed. Needless to say, all of the candidates for both parties are thoroughly reprehensible in one way or another. The exception is Ron Paul, currently serving in the House of Representatives, and currently the only conservative (in any real sense) who has thrown his hat into the ring (or “formed an exploratory committee”, as it is officially termed). Unfortunately (?), Paul has principles, and has stuck to them, so we can immediately disregard his chances for the Republican nomination he seeks. (When he fails to get the GOP nomination, he really ought to run as an independent, ideally with Jim Webb for vice-president. Then the warmongers will vote GOP, the baby-killers for the Dems, and the sane for Paul/Webb).

Nonetheless, it gets one thinking. What would one desire in a president? What policies would we want him to execute? Here are our humble suggestions, in no particular order:

• A prompt withdrawal from Iraq. This is too common sensical to be worth explicating.

• End NATO now. The Soviet Union has been gone for over a decade. End Europe’s gravy train so they can grow up and defend themselves. Phase out foreign military aid, while maintaining strong informal links with Canada, as well as the U.K., Australia, and New Zealand.

• Appoint constitutionalist judges. The Constitution says ‘X’ but radical judges say ‘Y’.

• Abolish the Departments of Homeland Security, Education, and Housing & Urban Development. The federal government has no constitutional power to interfere in education, housing, and urban development. As for “homeland security”, isn’t that what the Department of Defense is for? It’d probably be worthwhile to merge a few of the remaining departments.

• Balance the budget. Again, common sense.

• Abolish income tax. Income tax is wicked. It must be abolished, and if an alternative tax is necessary, then it should be a value added tax (VAT).

• Enforce immigration law. Rampant, uncontrolled immigration is an assault on our safety and security, as well as a grave threat to the earning power of American workers.

Above all: obey the Constitution. (Or at least be honest and get rid of it).

But really, this is not a political blog. If you want the goods, head over to Eunomia, where Daniel Larison really dishes out the good stuff. Mr. Larison is to be crisply saluted for not only undergoing the suffering entailed by paying attention to politics, but for going even further by cutting through the spin, the propaganda, and the nonsense like a hot knife through butter.

The Men Who Saved Quebec

The British Crown’s toleration of Catholicism in Quebec was cited by the rebel colonists of the 1770’s as, ironically, an ‘intolerable act’. That the Church of Rome, that bastion of backwards conservatism and slavish hierarchy, could be tolerated in the lands under the power of the British parliament riled the Whigs—the enlightened liberal progressives of the day. Indeed, Benjamin Franklin was even so foolish as to go to Quebec as an emissary of the ‘Continental Congress’ to persuade the natives to rebel against the Crown; Congress’s proposals to ban Catholicism and prohibit the use of the French language ensured he was not successful.

The modern orthodox opinion of historians on the Quebec Act of 1774—the act that granted toleration to the Church—is that it was merely a persuasive exercise to keep les Canadiens from rebelling. A 1989 book challenged this perspective, arguing instead that a handful of British aristocrats were determined to ensure that Quebec did not become another Ireland: where Protestant ascendancy was thrust upon an unwilling nation of Catholic nobles, merchants, and peasants.

The following review by Gary Caldwell was published in a Canadian journal in 2001.

|

Philip Lawson.

The Imperial Challenge: Quebec and Britain in the Age of the American Revolution. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. 192 pages. US$27.95. |

WHY REVIEW A BOOK published twelve years ago? I will explain. But first, let me tell you what it’s about.

When Britain took possession of Canada at the Treaty of Versailles in 1763, it faced an “imperial challenge:” how to integrate into the empire a society fundamentally different from England – in language, religion, and legal and political institutions. At the time, England was vigorously intolerant of Roman Catholicism or “popery,” the religion of its major enemies, France and Spain. British Protestantism was closely tied to the dominant Whig political ideology born of the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89. This doctrinal legacy prescribed that all British subjects were possessed of very definite and equal liberties, liberties endowed upon and limited to those who conformed to the Whig-Protestant definition of being British.

Hence the problem of 1763. English law and constitutional practice allowed only for protestant public officials and elected representatives. This meant excluding the entire French-speaking population, some 70,000 to 80,000 (the “new subjects”) as compared to some 300 Protestants established in the colony (the “old subjects”).

There were two schools of thought as to what should be done. The Whig position, favoured by much of the English political leadership and commercial class on both sides of the Atlantic, was not to accommodate the new subjects. It amounted to an attempted destruction of the local culture and to exclusion of the French-speaking population from all juridical, political and social positions, the hoped-for consequence being assimilation in one, perhaps two, generations. In short, what had been imposed in Ireland with the “protestant ascendancy.”

The opposing school of thought, still marginal in 1763, believed such a policy both impracticable and undesirable. James Murray, Lord Shelburne, Lord Dorchester (Gary Carleton), H. T. Cramahe, Alexander Wedderburn, Lord Mansfield and William Knox not only held that a Protestant ascendancy in Quebec would ruin the colony, they also believed that Quebec society was deserving of being preserved. Murray and Dorchester, who knew Quebec and its people, were adamant: the Canadians were a good “race”—in Murray’s words, “perhaps the best and bravest race on the globe” (p. 48)—and if protected they and their society would flourish and be loyal to the Crown. As it happened, all of these administrators and Crown legal officers, with the exception of Cramahe, were Anglo-Irish or Scottish; not one of them was of English origin.

But how were the Canadians and their culture to be accommodated? There were, as Lawson demonstrates, three distinct dimensions to this accommodation. The first was to respect the prevailing legal code and custom in civil and property matters; the second, to refrain from putting into place an English representative assembly because it would be the instrument of the 300 or so English and American voters in the colony. By far the most important was the third dimension, tolerance in Quebec of Roman Catholicism, which meant the nomination of a Bishop, the tithe and the right of Catholics to hold public office. Dorchester and the others successfully won these concessions in London by 1770, and they were contained in the Quebec Act in 1774, to the horror of much of English public sentiment, and especially the Americans who were more resolutely against “popery” and more Whig than the English themselves.

When Benjamin Franklin arrived in Montreal in 1775 with the invading army of the Continental Congress, he carried secret orders to ban the popish religion and the French language. Fortunately, the Americans were stopped in Quebec by no other than Dorchester, back from getting the Quebec Act through Parliament. At the head of an army of old and new subjects he broke the 1775-76 siege of Quebec.

Lawson’s interpretation is insightful in putting the events into the context of the Irish question. The major players in promoting the accommodation that became the Quebec Act had in mind “the Irish Imbroglio,” and were determined not to repeat the error of the “protestant ascendancy” in Ireland. The Quebec Act emerges clearly as the culmination of thoughtful and courageous policy formulation, a model of generous statesmanship. Hence, as Lawson goes on to argue, the “toleration” of Roman Catholicism in the Quebec Act paved the way for the British Acts of Toleration of 1778.

Lawson also helps understand why Murray, Dorchester and the others came to the conclusions they did about the Canathan problem. These men were essentially empirical conservatives who found the answer “in the past”—Quebec society as they had known it in the 1760s—and the “elastic nature of the British Constitution.” And here Lawson runs smack into the prevailing wisdom in Canadian historiography.

Lawson is insistent on the coincidental nature of any link between the Quebec Act and the American Revolution, affirming that there is no evidence that the inspiration for the Quebec Act was to placate the Canadians so as to keep them apart from the Americans. As this alleged link is one of the most tenacious myths in the Canadian historical consciousness, it is worth citing Lawson:

What can be done to dispose of this myth once and for all? Fifty years ago both Coupland and Burt said that they could find no evidence to justify such an assertion with Lanctot repeating the message in the 1960s, and nothing has yet come to light to contradict them (pp. 123-124).

When I first read this book in the early 1990s and realized how revolutionary his thesis was, I contacted Lawson to talk about his work. In passing, I mentioned that I supposed that The Imperial Challenge must have created quite a controversy in Canadian academic circles. His reply was “No, it has attracted very little attention in Canada.” (I never saw him again. I had arranged to see him a few years later, but just before I arrived in Edmonton he was admitted to hospital for terminal cancer and died shortly afterwards.) In subsequent years, I have been to McGill-Queens Press in Montreal to buy copies of his book to give to friends. Inquiring as to sales, I was told that only a few hundred copies had been sold. And, so far, I have encountered only one reference to Lawson’s book (in Yves Lamonde’s Histoire sociale des politiques au Quebec).

I was curious enough to go back recently to the reviews written when the book came out. There were 16 in Canada in French and English, in the United States and in the United Kingdom; all reviewers were quite positive except one (who wrote two of the reviews). They all commented positively on the extent and depth of the documentation, as well as the fresh reading from parliamentary debates, the personal archives of the principal players, and the press of the day. As for his interpretation of how the Quebec Act came to be, there is no suggestion that he was wrong in any respect. The negative reviewer suggests only that it is pretentious of Lawson to think he has added much to existing work on the Quebec Act. Of the 15 reviewers, a full half explicitly accredit Lawson with drawing out the intention of avoiding the error of Ireland.

Why, then, did a book, critically acclaimed by the author’s peers, which sheds considerable light on a pivotal period in the history of Quebec and Canada, drop out of sight in Quebec, and I suspect in the rest of Canada? Lawson calls into question the conventional wisdom on a very important subject in Canadian history, and no one takes notice. For instance, two prominent Canadians, Gerard Bouchard and John Raulston Saul, social thinkers who are presently reinterpreting Canadian history, make no mention, to my knowledge, of this book. A book that should have caused waves has generated scarcely a ripple.

Perhaps my assessment, as a non-professional historian, is faulty and I would welcome a demonstration of where I have erred. What are the factors that explain the untimely eclipse of Lawson’s work? Could it be simply that Canadian intellectual discourse is shallow, that a seminal work can be dropped into the water and hit bottom generating nothing more than a superficial ripple of perfunctory reviews and listings in compendiums? This is one possible explanation; a more certain explanation lies in ideology.

The ideological axe, starkly put, goes as follows. Quebec’s nationalist, republican-leaning contemporary intellectuals are loath to entertain the idea that a coterie of British Conservatives (half of them aristocrats) literally saved Quebec society by helping to keep it strong enough to withstand the renewed neo-liberal assault led by Lord Durham three quarters of a century later and, then, begin to rehabilitate the Quebec polity (under British institutions) in 1867. Such an idea being beyond the pale (again, the ghost of Ireland), they maintain the myth that the Quebec Act was political opportunism inspired by the American threat. What will it take for Quebec nationalist thinkers to recognize and appropriate the historical reality that Dorchester twice—in the Quebec Act and the siege of Quebec—saved Quebec? It is no exaggeration to assert that, had it not been for this one Anglo-Irish aristocrat, Quebec would likely have become anglicized and, subsequently, integrated into the American empire.

As for English-speaking Canada, the current crop of orthodox historians has long consigned our British imperialist past to the Marxist dust-heap of history: nothing good could possibly have come of it, all imperialisms being, by definition, bad. They are not about to disturb their orthodoxy that in contrast to Imperial Britain, which was incapable of any genuine sympathy for Quebec—only Canadian nationalist intellectuals are enlightened and respectful of Quebec society. So, they too maintain the “political opportunism” interpretation of the Quebec Act, despite its having been refuted by Lawson and his predecessors. Essentially, what we are seeing is a refusal to acknowledge a debt owed to dead white male Protestants (from Ireland and Scotland). But gratitude is not, as the contemporary French philosopher Alain Finkielkraut has pointed out, a hallmark of modern progressive thinkers.

I write this review knowing full well that it is too late for Lawson’s work to be rehabilitated. The Imperial Challenge is among the titles in this year’s McGill-Queen’s clear-the-warehouse sale.

Previously: Hitchcock in Quebec

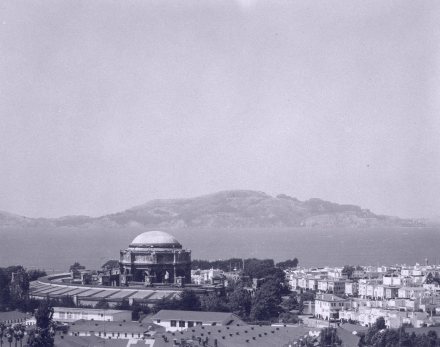

Volcanic Hills Loom Over the Italian Bay

OR NOT, to be precise. I found the above view of San Francisco rather charming, a touch Neapolitan even, and decided to share it. The domed building is the Palace of Fine Arts, designed by Bernard Maybeck for the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition. It used to exhibit various works of art, but is now an “interactive” science museum. The Palace of Fine Arts was actually built to last only two years but the San Franciscans couldn’t bring themselves to tear it down. Eventually, the elements took their toll and in the 1960’s, it was torn down and completely rebuilt to the same external design but with a permanent structure. (more…)

‘To a Fishfinger’

of our series introducing you to Peter Simple, the greatest columnist who ever was, we bring you this taste of the poetry of Julian Birdbath.

of our series introducing you to Peter Simple, the greatest columnist who ever was, we bring you this taste of the poetry of Julian Birdbath.

Birdbath is a character in the world of Peter Simple who lives at the bottom of a disused mine, alone but for his pet toad Amiel, writing poetry.

Among Birdbath’s putative translations of Esperanto verse is this delightful ode to the fishfinger – one of my favourite poems.

Thou shape impacted of Old Ocean’s heart,

With frost imbu’d and golden crumbs bedight,

Casual thy vending and thy worth too light:

How soon thy form symmetric must depart!

In rangéd boxes at the supermart

Thou bidest with thy fellows day and night,

Nor dream’st thou’ll’t scale some culinary height–

Who fries and serve thee needs no subtile art!

And yet for thee the stalwart seaman rov’d

’Mid tempests’ rage; and Iceland’s anger keen

Endur’d; nor glimpsed ’mid perils dire the end

Sublime: that thou, scorned digit, should’st be so lov’d

Dearer than pizza or th’ entinnéd bean,

For soliary men both food and friend!

edited and translated by Julian Birdbath

And the natives rejoiced…

One can find such amazingly random things on Youtube. Here we have a clip (3:09) of the native Fifers of Bell Baxter High School, of which the President of the St Andrews University Catholic Society is a distinguished alumnus, dancing my favorite reel (the name of which eternally escapes me).

And then there’s this clip (2:07) of Peter Sellers (or is it the Maximum Leader?) reciting “It’s Been A Hard Day’s Night” in the manner of Olivier:

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories