Unbuilt

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

An Early Proposal

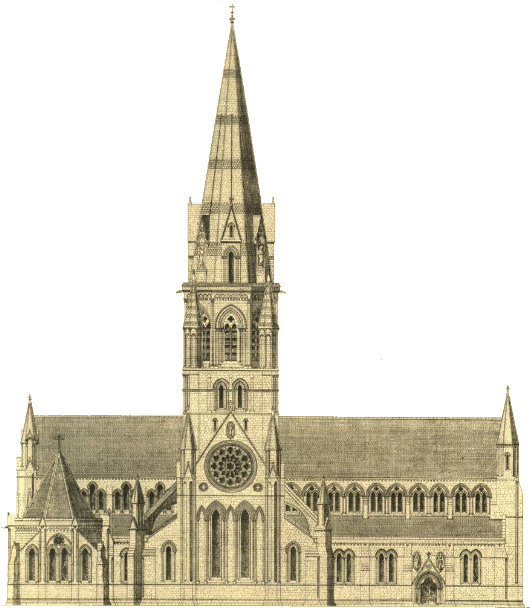

The Cathedral Church of St. Mary (Scottish Episcopal), Edinburgh.

Wisconsin Baroque, Priests, and Paper Architecture

Matthew G. Alderman

Taken from: Dappled Things, Ss. Peter & Paul, 2009

MY FAVORITE BUILDINGS never got around to being built. Some, like Sir Edwin Lutyen’s majestic design for Liverpool Cathedral, fell victim to budget cuts and the vagaries of history. Others were consigned by good taste, or occasionally outright timidity, to competition honorable mentions, and still others, like numerous student proposals or visionary dreams—like Boulée’s alarming hemispherical cenotaph for Newton, or an imaginary papal palace in Jerusalem cooked up by one of the votaries of the Vienna Sezession—weren’t terribly serious to begin with, unfortunately.

Note that I say favorite buildings, my own personal favorites, rather than the best or the most beautiful. Lutyens’ and Boulée’s fantasies may cross into that sublime territory of beauty by the power of their imaginative vision, but so many of the others owe their charm to their dreamlike extravagances, their intriguing if perhaps incomplete answers. An architect’s education lies in gathering up such fragmentary answers for the questions he will face down the road from clients and patrons. And therein lies the lure, and the value, of paper architecture.

I, like most of my colleagues, spent much of my time in school devising such useful fantasies, sometimes grand, sometimes small. Yet, they were not castles in the air. Each, while often existing in something like the best of all possible worlds in terms of budget and client, was grounded by an actual site and the laws of nature.

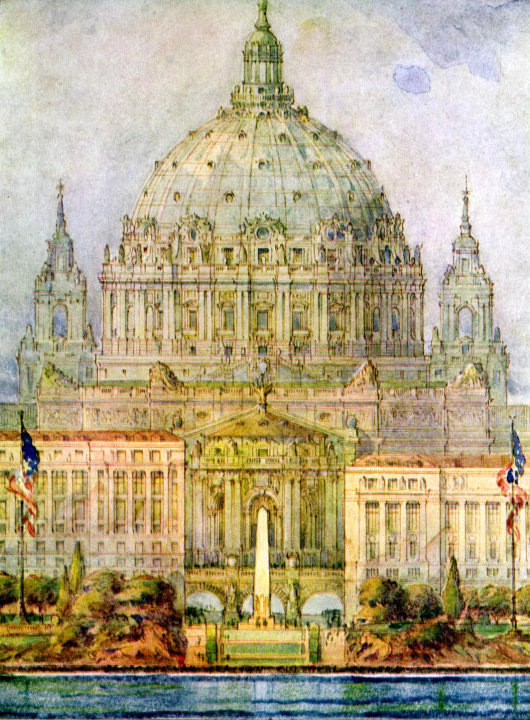

The most elaborate of all was my thesis project. It was an imaginary American seminary for a very real religious order, the fast-growing Institute of Christ the King, Sovereign Priest. This new congregation, dedicated to evangelization through the beauty of art, music, and the traditional Latin Mass, started out in, of all places, Gabon in Africa, but its present headquarters lies in Tuscany, in a villa bursting at the seams with seminarians in formation. While their ranks are dominated by Germans and Frenchmen, the increasing number of American clergy and their recent erection of a number of apostolates scattered across the Midwest suggested that a seminary in the United States, if not planned, might at least make for a plausible student project. Also, they seemed to have adventurous taste. I have since developed a passion for the Gothic but my first love has always been the Italian baroque. Perhaps they might be open to its vigorous beauty.

I garnered an award for the end result, the Rambusch Prize for Religious Architecture, and my putative patrons wanted copies of my enormous presentation watercolors to hang on their office walls—though, of course, the seminary would forever remain unbuilt. Its gigantic scale—typical for a student project—put it outside budgetary reach, unless, as someone cheerfully quipped, Bill Gates converted. Yet, the design was logical, consistent, and helped hone design skills I use every day at my drafting board.

The notion for the seminary came shortly after my first real-life encounter with the Institute’s work. My friends and I were road-tripping through the hill country of central Wisconsin, thick with vivid fall colors, and had just come back from a serene, silent low Mass and a long, talkative, private tour of St. Mary’s Oratory in Wausau. The Institute had transformed from a bland Midwestern Gothic to a dazzling near-replica of a fourteenth-century Bavarian court chapel. Bill Gates or no, these priests think big. Since then, they’ve overhauled a historic church in downtown Kansas City, and they’re presently turning their American priory from a burnt-out shell in a borderline south-side Chicago neighborhood into something out of Counter-Reformation Rome, and I have no doubt they’re going to succeed. Lest these projects seem like archaeological transplants, they are in fact derived from a logical extrapolation from local Catholic culture—Chicago’s colorful Polish cathedrals brought back to their ultramontane source, or, as I had just discovered, Midwestern Gothic returned to its Germanic roots. (more…)

Riparian Architecture

I’m not entirely sure of what project this is an architectural rendering, but I suspect it is an unbuilt project designed by Cass Gilbert for Blackwell’s Island in the East River, later known as Welfare Island and now Roosevelt Island. There were a number of schemes before the First World War (Thomas J. George was the author of one) for the construction of a new civic center for New York on the island, which is located right in the middle of the five boroughs.

Saskatoon Cathedral

Matthew Alderman’s hypothetical counter-proposal

Matthew Alderman has designed a hypothetical counter-proposal for the new Catholic cathedral in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan which is infinitely more beautiful than the ugly modernist thingamajig that the diocese is actually building. Matt elaborates upon the problematic nature of the modernist design here and here.

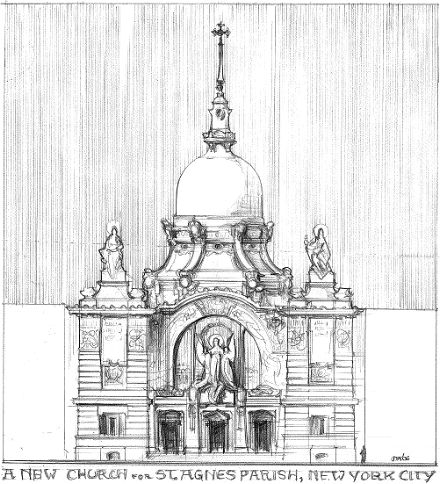

Vienna on 43rd Street

A WEEK AGO AFTER the 11 o’clock Sunday Mass at St. Agnes, Dino Marcantonio, Matt Alderman, and I stood in front of the church and fantasized about how we would fix the old place. Well, perhaps ‘old’ isn’t the right word for the place. While the parish was founded in the 1840’s, the current church building only dates from the late 1990’s, built after the old Victorian edifice was consumed by fire. As for design, its heart is in the right place, but as they say the Devil is in the details. The interior is marred by quite obviously large joints between component parts of arches and cornices and the exterior just looks fake. Is craftsmanship dead? No, but it helps to search it out instead of accepting just any old thing.

At any rate, Matt Alderman has thrown together these esquisses of what his St Agnes would look like, and it’s all rather Austrian. (more…)

Hypothetical Chicago Church

The clever kids over at Notre-Dame have struck again. Matthew Alderman (of Whapping fame) has published his hypothetical proposal for a church online and we thought we’d offer our most humble thoughts and comments upon the design. The Université de Nôtre-Dame du Lac over in South Bend, Indiana has arguably the best school of architecture in the country, if not all the Americas. Taking into account the state of most architecture schools these days, that isn’t saying much, but the School excels at teaching within the Western tradition of building, rather than inculcating the bland and soulless rejection of tradition which is modern architectural theory. You can see examples of the students’ works online at the School’s Student Gallery. (Of the rest, we found Lucas Hafeli’s art-nouveau mini-flatiron intriguing, as well as Erin Dwyer’s ferry terminal, and particularly enjoyed Brad Houston’s splendid arena). (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Gellner’s Prague December 19, 2024

- Monsieur Bayrou December 18, 2024

- Dempsey Heiner, Art Critic December 17, 2024

- Vote AR December 16, 2024

- Articles of Note: 12 December 2024 December 12, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories