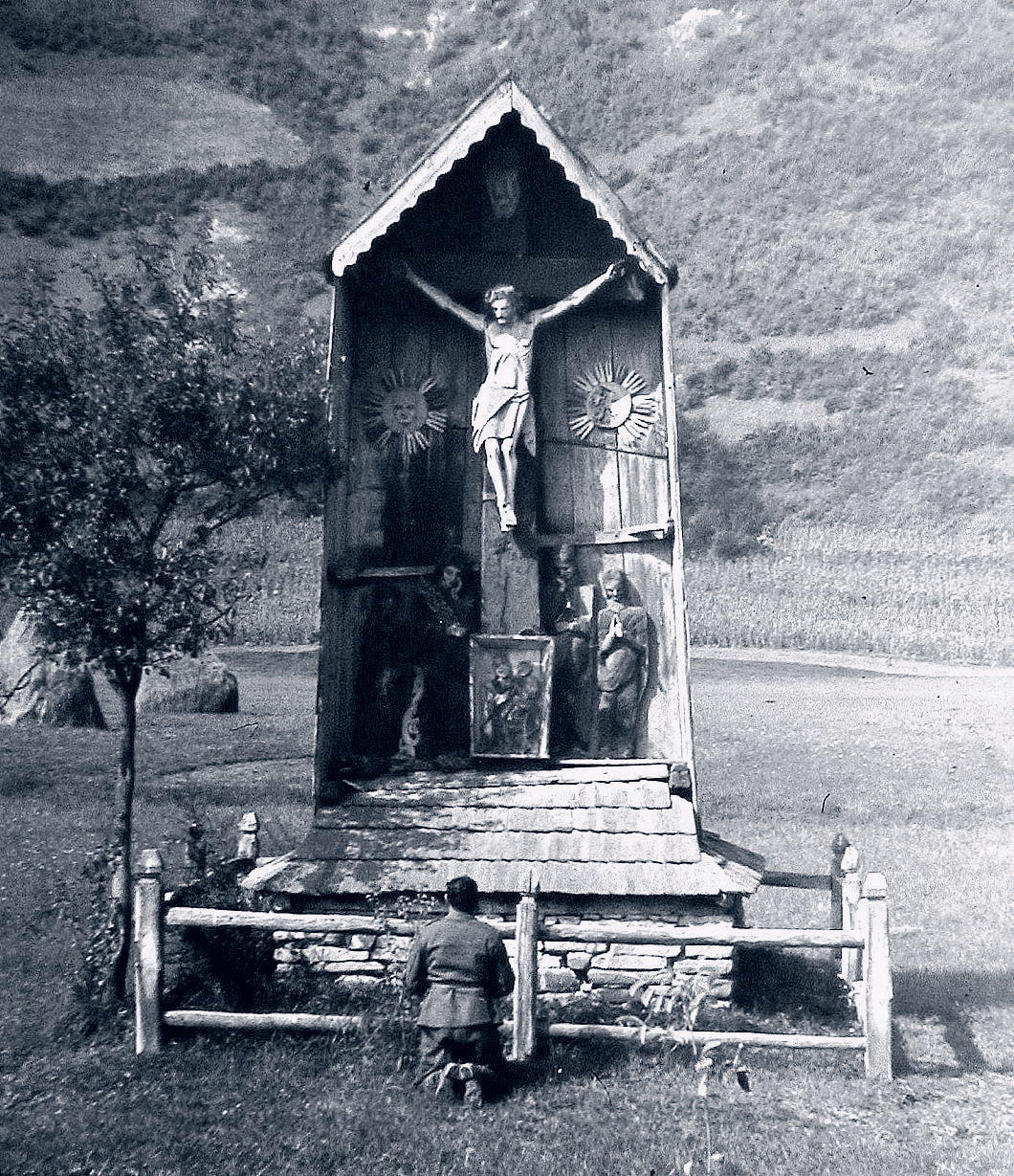

Transylvania

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

Caro had been a Nieman Fellow at Harvard studying urban planning and land use when he came up with the idea for the book. He thought it would take him nine months, but extensive research and over five-hundred in-person interviews meant it took eight years to complete.

Caro then started working on his study of Lyndon Baines Johnson, the first volume of which emerged in 1982 and the fifth (and final?) one he is still working on. (At the end of the fourth, LBJ had just become president.)

But where does he write? Christopher Bonanos of New York magazine finds out:

It’s an ageless space, one where it could be last week or 1950 inside, matter-of-fact and utilitarian. A couple of bookcases, a plywood work surface, corkboard with outlines tacked up, an old brass lamp, an underworked laptop for emails, a Smith-Corona typewriter. The desk chair is hard wood with no cushion. There’s a saltshaker next to the pencil cup for when Ina brings a sandwich out at midday. The desk has a big half-moon cutout, same as the one back in New York, so he can rest his weight on his forearms and ease his bad back. That arrangement was recommended by Janet Travell, the doctor who grew famous for prescribing John F. Kennedy his Boston rocker. She, with Ina, is a dedicatee of The Power Broker.

He bought the prefab shack, he says, from a place in Riverhead for $2,300, after a contractor quoted him a comically overstuffed Hamptons price to build one. “Thirty years, and it’s never leaked,” he says. This particular shed was a floor sample, bought because he wanted it delivered right away. The business’s owner demurred. “So I said the following thing, which is always the magic words with people who work: ‘I can’t lose the days.’ She gets up, sort of pads back around the corner, and I hear her calling someone … and she comes back and she says, ‘You can have it tomorrow.’”

Does he write out here every day? “Pretty much every day.” Weekends too? “Yeah.” Does he go out much while he’s on the East End? “We have two friends who live south of the highway, and I said to Ina, aside from them, I’m not going this year.” There are other writer friends nearby in Sag Harbor, and they get together, but at this age, Caro admits a little sadly, they’re thinning out. He’ll be 89 this fall.

■ George Grant is a still-underappreciated giant of political thinking in the English-speaking world. He is too little known outside his native Canada, which he sought to defend from the undue overwhelming influence of its sparkling and glamourous southern neighbour. Next year marks the sixtieth anniversary of his Lament for a Nation.

Of all people, a research fellow at Communist China’s Institute for the Marxist Study of Religion — George Dunn — has written a thoughtful introductory overview of Grant’s life and thinking: George Grant and Conservative Social Democracy in Compact.

■ Katja Hoyer mused on an overlapping theme in a recent Berliner Zeitung column which she has helpfully presented in English as well:

A diplomat close to the SPD recently told me that he couldn’t understand why working-class people in particular voted for the AfD. Things weren’t so bad for them, after all. I didn’t bother pointing out that rampant inflation, high energy prices and rising rents have had a hugely detrimental effect on the living standards of people with low and middle incomes because his analysis completely misses the point.

Germany’s working-class voters, Katja argues, feel forgotten by the parties founded to represent them.

■ Since the fall of the Berlin Wall — and earlier in Angledom — political conservatism has effectively been taken over by economic liberalism.

This has denied the centre-right from learning from and deploying useful experience from outside liberalism, with the wisdom of figures as varied as Benjamin Disraeli, Giorgio La Pira, Charles de Gaulle, and Thomas Playford essentially ignored or sidelined.

Kit Kowol’s new book Blue Jerusalem: British Conservatism, Winston Churchill, and the Second World War explores the visionary side of wartime Conservatism. Dr Francis Young offers his take on Tory utopias in The Critic.

■ From a similar era, Andrew Ehrhardt writes at Engelsberg Ideas on Ernest Bevin and the moral-spiritual dimension of British foreign policy.

■ Our friend Samuel Rubinstein has studied at Oxford, Leiden, and the Sorbonne — technically the oldest universities in their three respective countries (although we all know that Leuven is in fact the doyen of Netherlandish academies).

Sam offers an incredibly interesting comparison of the experiences of these three institutions in a humble essay on his Odyssean education:

I arrived in Leiden, armed with my phrase-book, with some ambitions of learning Dutch. The first blow came at the Starbucks in the train station, when the barista answered my Ik wil graag in English without hesitating. The second came the following day when I tried again, at a different café – only this time it seemed that the barista (Spanish? Italian?) didn’t know much Dutch either: even the natives were placing their orders in English. So I gave up – save one hobby, reading Huizinga in the original. I got myself an attractive coffee-table edition of Herfsttij and managed a page or so a day, strenuously piecing it together from my English, German, and smattering of Old English. I still haven’t the faintest idea how to pronounce any of it.

■ And finally, those of us who love Transylvania will enjoy Toby Guise’s summary of the Fifth Transylvanian Book Festival in The New Criterion.

Sibiu/Hermannstadt

SIBIU’s name comes from a Bulgar-Turkic root word meaning “rejoice”, and having spent a few days in the city I can see why. It is handsome, clean, and clearly well looked after — perhaps well loved is the better term.

Unsurprisingly, the mayor partly responsible for this state of affairs was much vaunted for his efforts, to the extent that the Romanians elected him president of the entire country (and this despite him being an ethnic German).

As in all of Transylvania, there is a long history of mixture here, and while the past hundred years have seen a massive collapse in the Hungarian, German, and Jewish populations, many of them persevere all the same, sometimes even flourishing.

Hungarians are the largest and most visible minority in Transylvania — once the dominant people of this province of the Crown of St Stephen — but here in Sibiu they play second-fiddle to the Germans.

Arriving in the Church of the Holy Trinity in the great square for the Hungarian Mass on Sunday, the congregation at the Mass in German preceding it was still filtering away and clearly is the main event of the parish.

The Germans — or Saxons as they are often known — are today under two per cent of the city’s population but, as elsewhere, the Teutonic reputation for competence and efficiency means that a great many ethnic Romanians vote for the Germans’ party, the Democratic Forum of Germans in Romania.

When mayor Klaus Iohannis was elected to the Romanian presidency, he was succeeded as mayor by another member of the German community, the rather elegant Astrid Fodor.

But what of the ethnic Romanians that today make up ninety-five per cent of Sibiu’s townfolk? They are anything but ethnic chauvinists, and seem keen to preserve the traditions of the city and the province, and especially to highlight Sibiu’s distinctiveness. Those I had the pleasure of interacting with were effortlessly warm, courteous, and inviting. Their language is alluringly if mistakenly familiar.

Curiously, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg maintains a consulate here in Sibiu / Hermannstadt with the ostensible excuse that the former German dialect of the town is a close relative of Luxemburgish. The connection bore fruit when Sibiu and Luxembourg City shared the honour of being European City of Culture in 2007.

It was around that time that Forbes magazine rated Sibiu as the seventh most idyllic place to live in Europe — ahead of Rome and just behind Budapest. While such ratings are always arbitrary, I can’t help but share their desire to praise this felicitous city. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Articles of Note: 27 January 2025 January 27, 2025

- Spooks’ Crown January 23, 2025

- Jesuit Gothic January 23, 2025

- Christ Church December 29, 2024

- A Christmas Gift from the Governor December 24, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories