Seventh Regiment

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

A Christmas Gift from the Governor

Just in time for Christmas: some excellent news for the Knickerbocker Greys.

Her Excellency the Governor of the great Empire State of New York has signed into law a requirement that this venerable Manhattan cadet corps be allowed to remain in its quarters at the old Seventh Regiment Armory (as The New York Sun reports).

Over recent years the Park Avenue Conservancy has restored the building — a gem of American architecture and interior design — but also effectively expelled the military units still based at the Armory.

The Greys managed to hold out in their “800-square-foot broom closet” (as the New York Post described it) but the Conservancy moved to evict the youth group in 2022. The Greys have fought the eviction in court.

In June a bipartisan bill guaranteeing the Knickerbocker Greys “access and use for permanent headquarters” of the Armory “for the purposes of programming during periods which are not periods of civil or military emergency” passed in the State Assembly and Senate but has only now been signed into law.

The hope is this new legislation will persuade the Conservancy to drop their eviction proceedings which the Greys have been challenging.

Season’s Greetings from the Seventh

Alas, the Seventh Regiment Mess is no more, though we had a few family Christmas-time (and other) celebrations there in its final years.

Happy days when Linda MacGregor was at the helm of it.

Messing About in Old New York

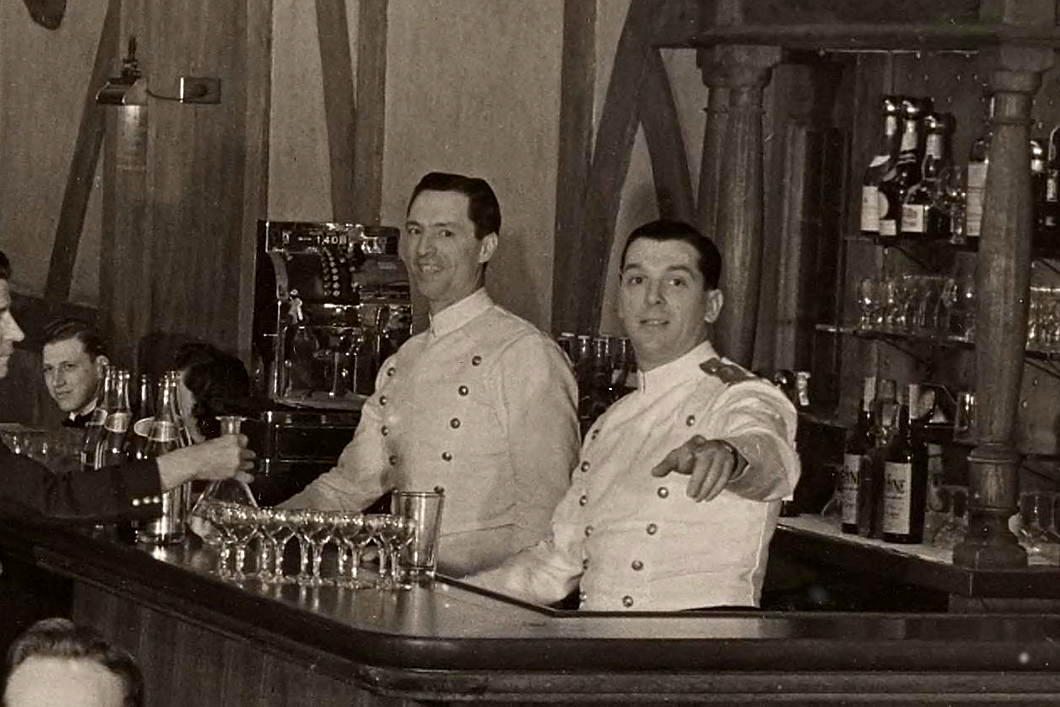

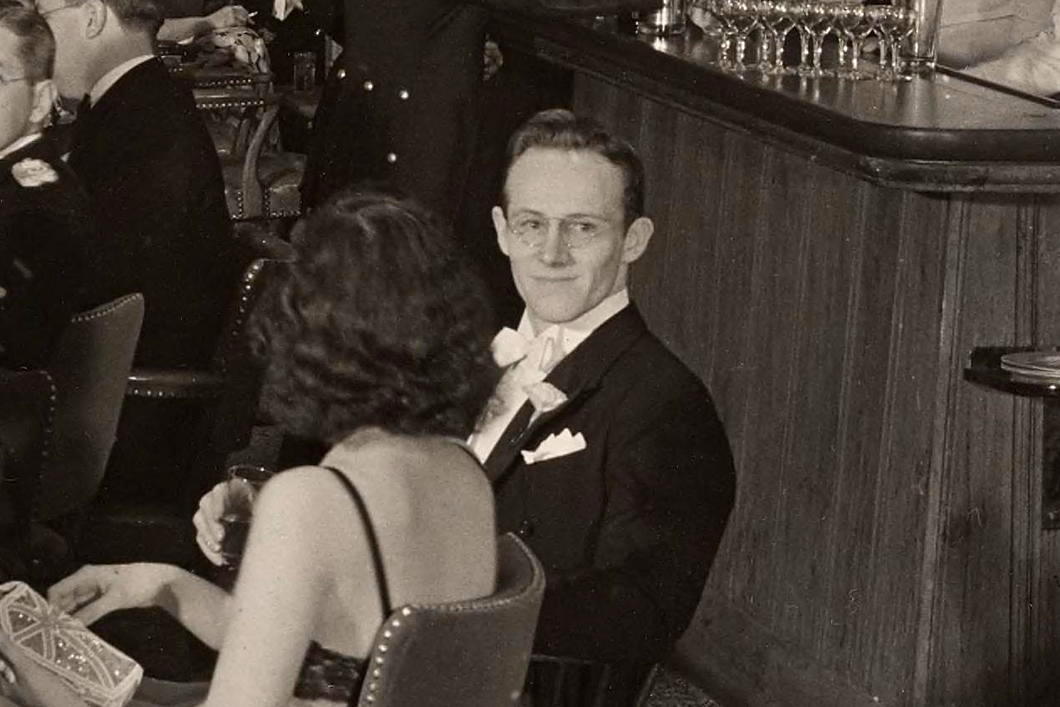

In the collections of the New-York Historical Society there is a photograph deposited amidst the archives of the Seventh Regiment Gazette.

The scene is the Appleton Mess of the Seventh Regiment Armory on Park Avenue, where Company B of the “Silk-Stocking Regiment” was celebrating its one-hundred-and-thirty-fourth birthday.

It was May 1940. The other side of the Atlantic Ocean, British troops were evacuating from Norway, sparking the debate in the House of Commons that would lead to Winston Churchill being appointed Prime Minister.

But on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, all was still peaceful and calm.

With a packed calendar of events, the social life of B Company was as much of a whirl as any other in the Seventh Regiment.

“The members of the Second Company greeted the onrushing spring with a cocktail party and dance on the afternoon of February 11th,” the Gazette reported. “The time-stained rafters of the Veterans Room echoed back as melodious a medley of sweet, swing, and hot as these old ears have heard in many a year.”

“The spaghetti lovers are still meeting down at Tosca’s on Tuesdays,” the Gazette continued. “All members who drop in on this crowd are warned beforehand to eat fast and keep an eye on their plate. A darting fork awaits all unwatched portions and men have been known to sit down to a full dish of Italian cable only to arise half famished.”

Company B’s Entertainment Committee also found time for a Supper Dance at the end of March that year: “When Charley Botts heard ‘In The Mood’ he gathered up the jitterbugs and sent them scampering around in a breathless Big Apple, much to the delight of the wiser and unbruised amongst us who resisted his wiles.”

“Several of the more energetic members closed the evening by visiting that well-known late spot, the Kit-Kat Club, and are now offering mortgages on the family homestead to settle future bills.”

All the faces, the mode of dress — it’s a picture of a vanished New York, a year and a half before the attack on Pearl Harbor. (Incidentally, December 7, 1941 was also the day Col. Cusack — aka ‘Uncle Matt’ — was baptised.)

On another level, it looks just like the Seventh Regiment Mess I knew from my childhood, when it was in the firm but welcoming hands of Linda MacGregor.

The building has been restored physically but since the military was kicked out it is a beautiful but lifeless hulk, preserved as if in formaldehyde and reduced to being a mere “venue”.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

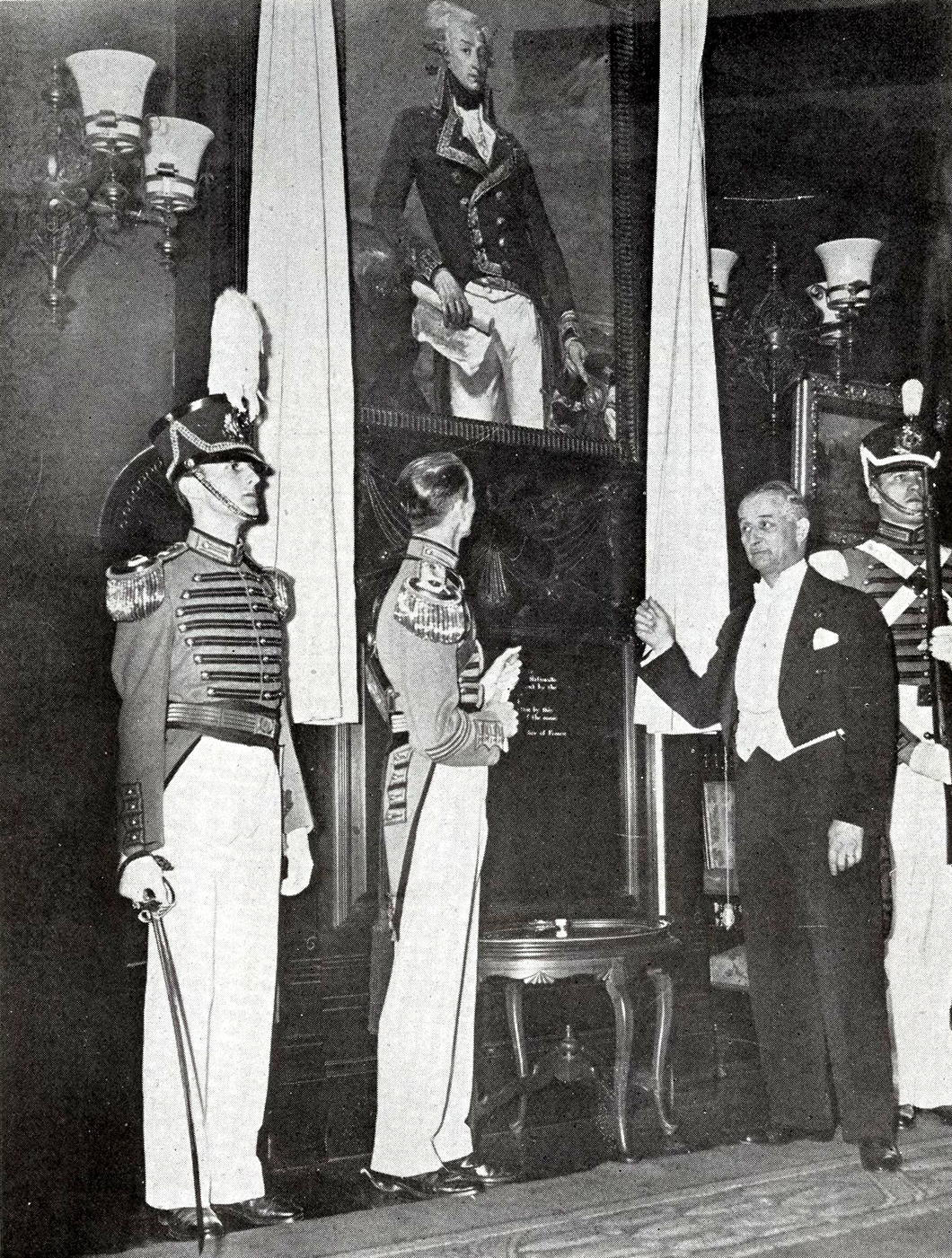

Lafayette at the Seventh

For the first century or so in the history of the United States, there was no more popular Frenchman in America than the Marquis de Lafayette. This nobleman of the Auvergne was an officer in the King’s Musketeers aged 14 and was purchased a captaincy in the Dragoons as a wedding present aged 18 in 1775. Within a year the rebel faction in North America had sent Silas Deane of Groton to Paris as an agent to negotiate support from the French sovereign, but Paris acted cautiously at first.

Lafayette — a young aristocratic freemason and liberal with a head full of Enlightenment ideas — escaped to America in secret and was commissioned a major-general on George Washington’s staff in the last of his teenage years.

Given his relative youth, Lafayette inevitably turned out to be the final survivor of the generals of the Continental Army, and his 1824 trip to the United States solidified his popularity. He visited each of the twenty-four states in the Union at the time, including New York where the predecessor of the Seventh Regiment named itself the National Guards in honour of the Garde nationale Lafayette commanded in France.

This was the first instance of an American militia unit taking the name National Guard, which in 1903 was extended to all of state militia units which could be called upon for federal service.

In honour of this connection and on the centenary of Lafayette’s 1834 death, the French Republic presented the Seventh Regiment with a copy of Joseph-Désiré Court’s portrait of the general that hangs in the 1792 Room of the Palace of Versailles. The Seventh set this in the wall of the Colonel’s Reception Room in their Armory, facing a copy of Peale’s portrait of General Washington.

The privilege of unveiling the portrait went to André Lefebvre de Laboulaye, the French Ambassador to the United States, who was given the honour of a full dress review of the Seventh Regiment on Friday 12 April 1935 before a crowd of three thousand in the Amory’s expansive massive drill hall.

Also present at the occasion was his son François, who eventually in 1977 stepped into his late father’s former role as French Ambassador to the United States. His Beirut-born grandson Stanislas served as French Ambassador to Russia 2006-2008 before being appointed to the Holy See until 2012. In April 2019, Stanislas de Laboulaye was put in charge of raising funds for the rebuilding of Notre-Dame following the fire that devastated the cathedral.

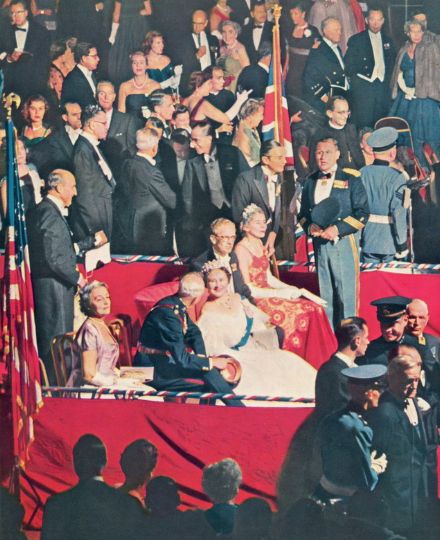

The Queen at the Armory

Queen Elizabeth II & the Duke of Edinburgh attend a ball in their honour at the Seventh Regiment Armory in New York; October, 1957.

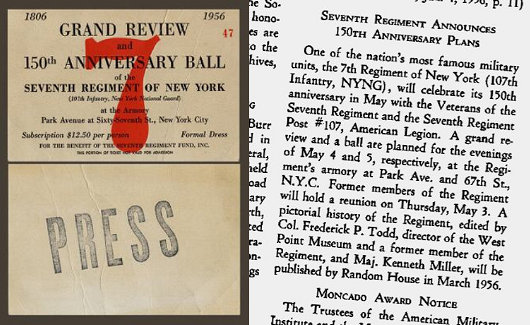

200 Years was an Empty Anniversary for New York’s ‘Gallant Seventh’

Flipping through a military journal from early 1956, I stumbled upon a rather depressing note announcing the Seventh Regiment’s plans for celebrating its 150th anniversary. A reunion of old comrades on Thursday May 3, then a grand review the following day, and topped off by a formal ball on the evening of Saturday May 5 at the regiment’s beautiful armory on Park Avenue at 67th Street.

Why should such a splendid celebration spark dour thoughts? Chiefly because, having survived over a century and a half since the unit was founded amidst pints of ale in the Shakespeare Tavern on the corner of Nassau and Fulton, the Seventh Regiment was abolished before it could celebrate its 200th anniversary in 2006. The Seventh was deactivated as a regiment in 1993, though its “lineage” was transferred to the 107th Corps Support Group, which in 2006 was “consolidated” into the 53rd Army Liaison Team. The regiment’s unique collection of historical artifacts — the legal property of the Veterans of the Seventh Regiment — was seized by the State in an act of highly dubious constitutionality and its armory, built without a cent of public money from the pockets of the regiment’s members in the 1880s, was also taken and transferred to a conservancy to run it as an events & performing arts venue, over protests from both veterans groups and the local community.

Why should such a splendid celebration spark dour thoughts? Chiefly because, having survived over a century and a half since the unit was founded amidst pints of ale in the Shakespeare Tavern on the corner of Nassau and Fulton, the Seventh Regiment was abolished before it could celebrate its 200th anniversary in 2006. The Seventh was deactivated as a regiment in 1993, though its “lineage” was transferred to the 107th Corps Support Group, which in 2006 was “consolidated” into the 53rd Army Liaison Team. The regiment’s unique collection of historical artifacts — the legal property of the Veterans of the Seventh Regiment — was seized by the State in an act of highly dubious constitutionality and its armory, built without a cent of public money from the pockets of the regiment’s members in the 1880s, was also taken and transferred to a conservancy to run it as an events & performing arts venue, over protests from both veterans groups and the local community.

Remembering the Seventh

It is entirely appropriate that November 11 — Armistice Day — both falls during the month of the Holy Souls and on the feast of St. Martin of Tours. It’s not unlikely that the souls in Purgatory added their voices to plead for peace that November of 1918, and St. Martin, who had himself been a Roman soldier, was no doubt leading the cause from Heaven. (Indeed, his father having been in the Imperial Horse Guards, St. Martin was born into a military family).

The Knickerbocker Greys

The Knickerbocker Greys, the Upper East Side corps of cadets, is celebrating its 125th year in existence. Both the Times and the Sun have featured articles on the Greys:

‘Celebrating 125 With the Knickerbocker Greys‘ by Gary Shapiro (The New York Sun)

‘Manhattan’s Littlest Soldiers‘ by Eric Königsberg (The New York Times)

Above: A mother mends a cadet’s uniform.

Below: Cadets assembled in an Armory corridor. (Note the interior scaffolding due to the State’s grievous neglect of the Armory).

The Queen Mother in New York, 1954

In 1954 Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother (n.1900, m.2002) visited New York to accept an educational fund raised by Americans in memory of the late King George VI. On the evening of November 1 of that year, the Seventh Regiment entertained Her Majesty with a special ball held in her honor at the Armory on Park Avenue (view above). Her Majesty also visited the Cathedral of St. John the Divine where she was received by the (Episcopal) Bishop of New York, the Dean, and the clergy of the Cathedral. The three stone blocks on the façade seen in the view below have since been sculpted.

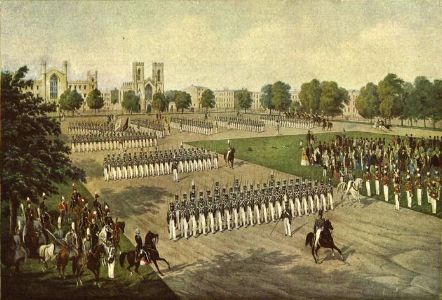

The 7th Regiment in Washington Square

Entitled “National Guard – 7th Regiment New York State Militia”, this mid-nineteenth century view shows the famous 7th Regiment of New York, nicknamed the Silk-Stocking Regiment, parading in Washington Square. In the background can be seen the University of the City of New York and the Church of St. Thomas, which has since moved to Fifth Avenue in Midtown.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories