Science

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

An African View of the Heavens

Catholic Clerical Skygazers at the Cape of Good Hope

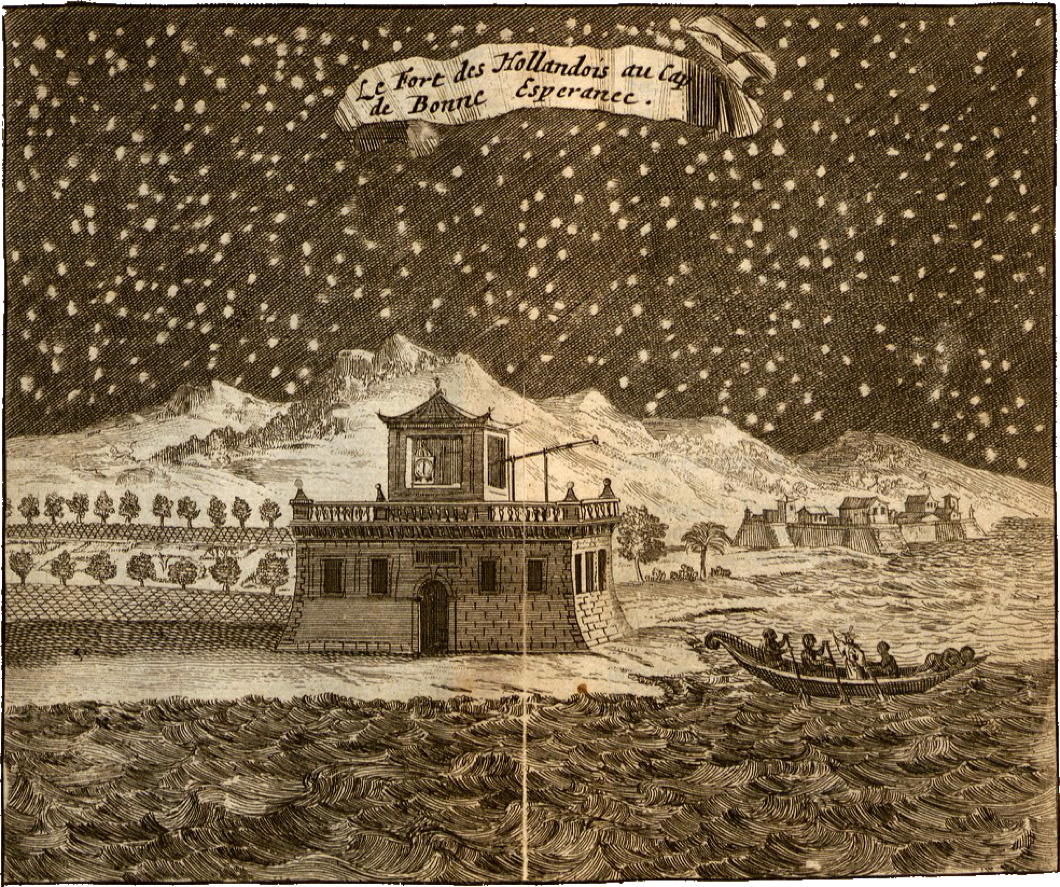

In 1685, the Jesuit mathematician, astronomer, and not-quite-secret-agent Fr Guy Tachard stopped off at the Cape of Good Hope en route to Siam as an emissary of the Sun King, Louis XIV.

Given Dutch hostility both to the French and to Catholicism, Père Tachard was surprised by the generous welcome provided by the governor, Simon van der Stel. Tachard was allowed to set up an astronomical observatory in the Company’s Gardens (today Cape Town’s equivalent of Central Park). No sooner had this happened than the clandestine Catholics of the colony searched the priests out.

“Those who could not express themselves otherwise knelt and kissed our hands,” one of the expedition’s priests wrote. “In the mornings and evenings they came privately to us. There were some of all countries and of all conditions: free, slaves, French, Germans, Portuguese, Spaniards, Flemings, and Indians.”

Those who spoke French, Latin, Spanish, or Portuguese were lucky enough to have their confessions heard but one thing was absolutely forbidden: the Mass. The Dutch authorities would not permit Mass to be offered on land, and local inhabitants were forbidden from visiting the French ships.

Once, while the priests took ashore a microscope covered in beautiful Spanish gilt leather, locals suspected them of trafficking in the Blessed Sacrament such that the clerics were forced to demonstrate the use of the microscope to prove they were heeding the Governor’s instructions.

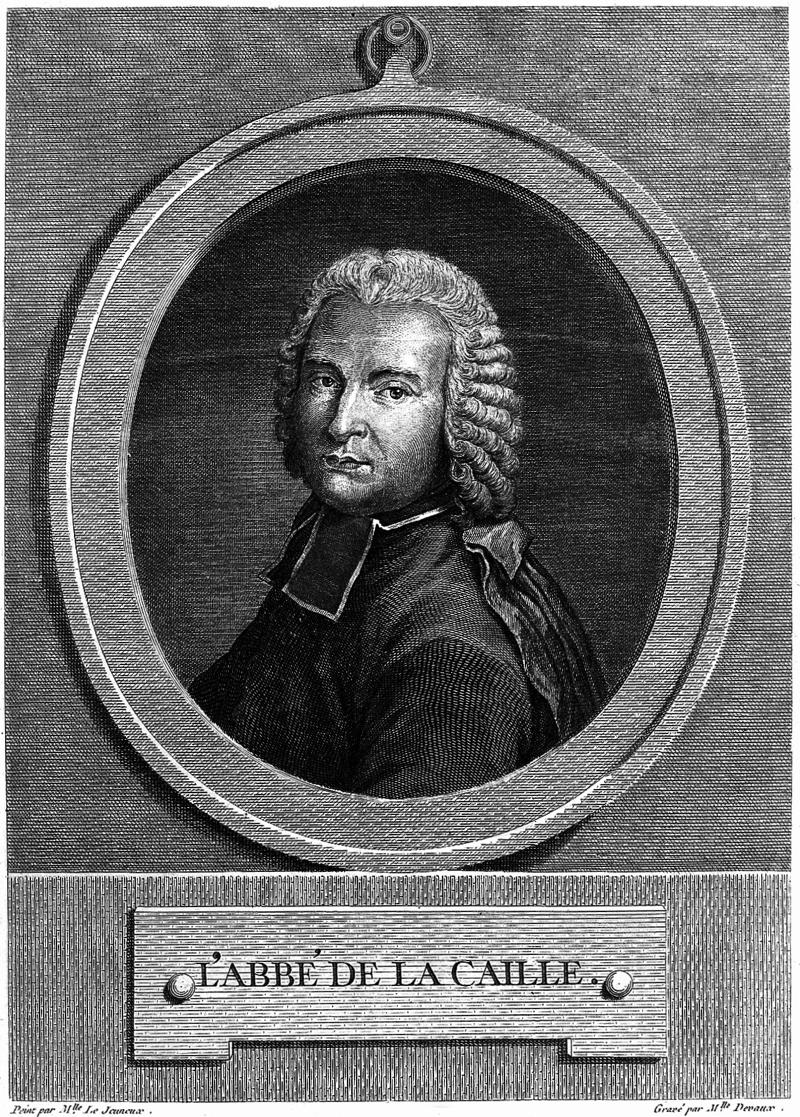

A century later another French cleric-astronomer, the Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, made his way to the Cape during Ryk Tulbagh’s time as Governor of the Dutch colony.

A century later another French cleric-astronomer, the Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, made his way to the Cape during Ryk Tulbagh’s time as Governor of the Dutch colony.

As a mere deacon Lacaille could not offer the Mass and we know little of his relations with any remaining Catholics at the Cape.

There’s no doubt, however, that his contribution to astronomy while in South Africa was significant: Lacaille’s two years of astronomical observation there were prolific in their results. Of the 88 constellations currently recognised by the International Astronomical Union, fourteen were named by Lacaille — including the constellation Mensa (“table”) which took its name from the Latin for Cape Town’s Table Mountain.

Mensa remains the only constellation named after a feature on Earth, so there is a little bit of South Africa that is visible in the night sky anywhere south of the fifth parallel of the northern hemisphere.

‘The greatest and most successful pseudoscientific fraud I have seen in my long life’

Harold Lewis, eminent American physicist, resigns from learned society which has helped stifle the scientific debate over global warming

The physicist Harold Lewis has resigned from the American Physical Society over the learned group’s efforts to suppress scientific inquiry and debate into global warming and climate change. Prof. Lewis, who is Emeritus Professor of Physics at the University of California Santa Barbara, cited the leaked ‘ClimateGate’ e-mails as proof of scientific fraud. His resignation letter (reproduced below) speaks of ‘the money flood’ and alludes to President Eisenhower’s warning in his farewell address of 1961 to guard against ‘the unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, [of] the military-industrial complex’.

While he has refrained from coining the phrase, Prof. Lewis’s remarks suggests the massive amount of funding available for climate research has created a climate-industrial complex pressuring and perverting the scientific profession and leading it away from an environment of free inquiry.

“[T]he global warming scam, with the (literally) trillions of dollars driving it,” Prof. Lewis wrote, “has corrupted so many scientists, and has carried APS before it like a rogue wave. It is the greatest and most successful pseudoscientific fraud I have seen in my long life as a physicist.” (more…)

Fated

WHETHER Parliament approves “therapeutic cloning” or not, will it make any difference in the long run? Whatever scientists can do, that will be done. Public opinion, at first aghast at artificial insemination and other landmarks on this infernal road, has largely come to accept them. So it is likely to be with this latest triumph.

“Science has put into our hands innumerable gifts that we can use either for good or ill.” This mantra, once regularly intoned, has become less popular now that many of these gifts are plainly seen to be used for ill.

“Science has put into our hands innumerable gifts that we can use either for good or ill.” This mantra, once regularly intoned, has become less popular now that many of these gifts are plainly seen to be used for ill.

A new palliative has appeared instead: it says that we must be kept well informed about the latest scientific developments, as well as learning more about science and scientific methods, so that we can decide for ourselves whether we want these gifts or not.

But who are “we”? Would it make any difference if we said we did not want them? Would it make any difference if some scientists themselves decided they were too dangerous to proceed with? Others would somehow, somewhere, carry on the work. The progress of science and technology which has seized upon our world seems irreversible, even fated.

Will it, as in some environmentalist fantasy, gradually diminish in strength and become humanly manageable in a new, green and “sustainable” world? Or will it, as seems more likely, proceed to a catastrophic end?

Stellenbosch Scientists Invent Cheap & Easy Water Filtration for the Masses

Prof. Eugene Cloete and his colleagues at the Water Institute of the University of Stellenbosch have come up with a helpful solution to the problem of drinking water in developing countries. The professor invented an inexpensive, teabag-like sac of nano-fibres — each about one hundredth the width of a human hair — which is secured into the lid of a reusable vessel. The water then passes through the filter secured in the lid and is thereby purified and made much more potable for human consumption.

The importance of the breakthrough is not only in its ease, but in its cheapness. Prof. Cloete estimates it would cost just three cents a litre to produce water that is the same quality level as bottled water (If he means three ZAR cents, then that is about equivalent to half a U.S. dollar cent — half a penny). Numerous foundations have expressed interest in a major roll-out of the cheap and efficient new filter system invented at Stellenbosch University.

In the video above, Prof. Eugene Cloete and Dr. Marelizes Botes explain the use and the science of the teabag filter, though I’m afraid the science of it goes a bit beyond my layman’s knowledge. The professor does manage to work in a bit of Afrikaans at the end of the video though.

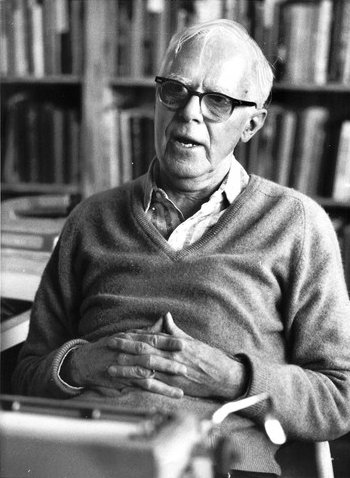

Martin Gardner

IT’S ONE  OF those strange things that I always automatically assume that anyone I know or have had dealings with cannot, by any stretch of the mind, be considered famous or well-known. The falseness of this assumption was made apparent to me when I picked up this week’s Economist after it arrived through the mail slot. As usual, there were a number of fascinating and well-informed articles, on the airlines of the Gulf, on the Colombian election, a special report on South Africa, and more. But then I finally reached the end pages and read the full page obituary of “Martin Gardner, man of letters and numbers,” who died on May 22nd at 95 years of age.

OF those strange things that I always automatically assume that anyone I know or have had dealings with cannot, by any stretch of the mind, be considered famous or well-known. The falseness of this assumption was made apparent to me when I picked up this week’s Economist after it arrived through the mail slot. As usual, there were a number of fascinating and well-informed articles, on the airlines of the Gulf, on the Colombian election, a special report on South Africa, and more. But then I finally reached the end pages and read the full page obituary of “Martin Gardner, man of letters and numbers,” who died on May 22nd at 95 years of age.

I never met Mr. Gardner but interacted with him several times during my New Criterion days by phone, and good old-fashioned post. He was a regular though not a frequent contributor to the magazine and was singular in that he was the only writer with whom the editor did not have the option of contacting via that nebulous mystery called the world-wide web. It was often, I confess, a source of some frustration that one would have all ones eggs in a row regarding pieces edited and signed off, and then there’d be something to do with Martin Gardner’s work and one would think “Blast! You mean I’ve got to stick this in an envelope to get the final OK?” Of course, when The New Criterion was founded, there was no internet, so there was a time when the whole magazine — indeed when every magazine — was put together via what I called the Martin Gardner method.

This aspect notwithstanding, it was always a pleasure working with Mr. Gardner, who was unfailingly polite over the phone when he would call in with his changes to our edits. It’s one of those inevitable aspects of death that one often discovers more interesting facts about the deceased than one ever knew while he was alive. In Martin Gardner’s case, it’s that this science maven published a number of annotated editions of works by G. K. Chesterton.

Roger Kimball writes of his last contact with Martin Gardner just a short time ago:

I wrote to tell him about the coincidence that a good friend now occupies the house he lived in for decades on Euclid Avenue (how’s that for an appropriate name?) in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. I discovered this quite by accident. My wife and I were having dinner with a few other people at our friends’ house. I can’t remember Gardner’s name came up, but when it did I mentioned that he had lived for many years in Hastings-on-Hudson. “Yes,” said my friend, “and he lived in this very house.” One of the other couples present also knew Gardner. They recalled the time he invited them, shortly after they had moved to the neighborhood, to his house for drinks. Would it be alright if they brought their young children along, since no baby-sitter was available? Of course, nothing could be more agreeable! They arrived and Gardner proceeded to entertain the children with magic tricks for two hours.

My favourite story, however, is that he once wrote a devastating review of one of his own books and got it published under a pseudonym in the New York Review of Books. While he was a noted contributor to numerous sceptical reviews, he did come to a belief in God late in his life. “His declaration,” The Economist writes, “of this belief caused, he admitted, profound shock to those who knew him only as a sceptic. But there was too much playfulness in Mr Gardner to make him yield entirely to reason. His faith, he said, was based on an “emotional turning of the will”, unsupported by logic or science. It was his way, perhaps, of recognising that mind and man are not synonyms.”

Requiescat in pace.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories