Quebec

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

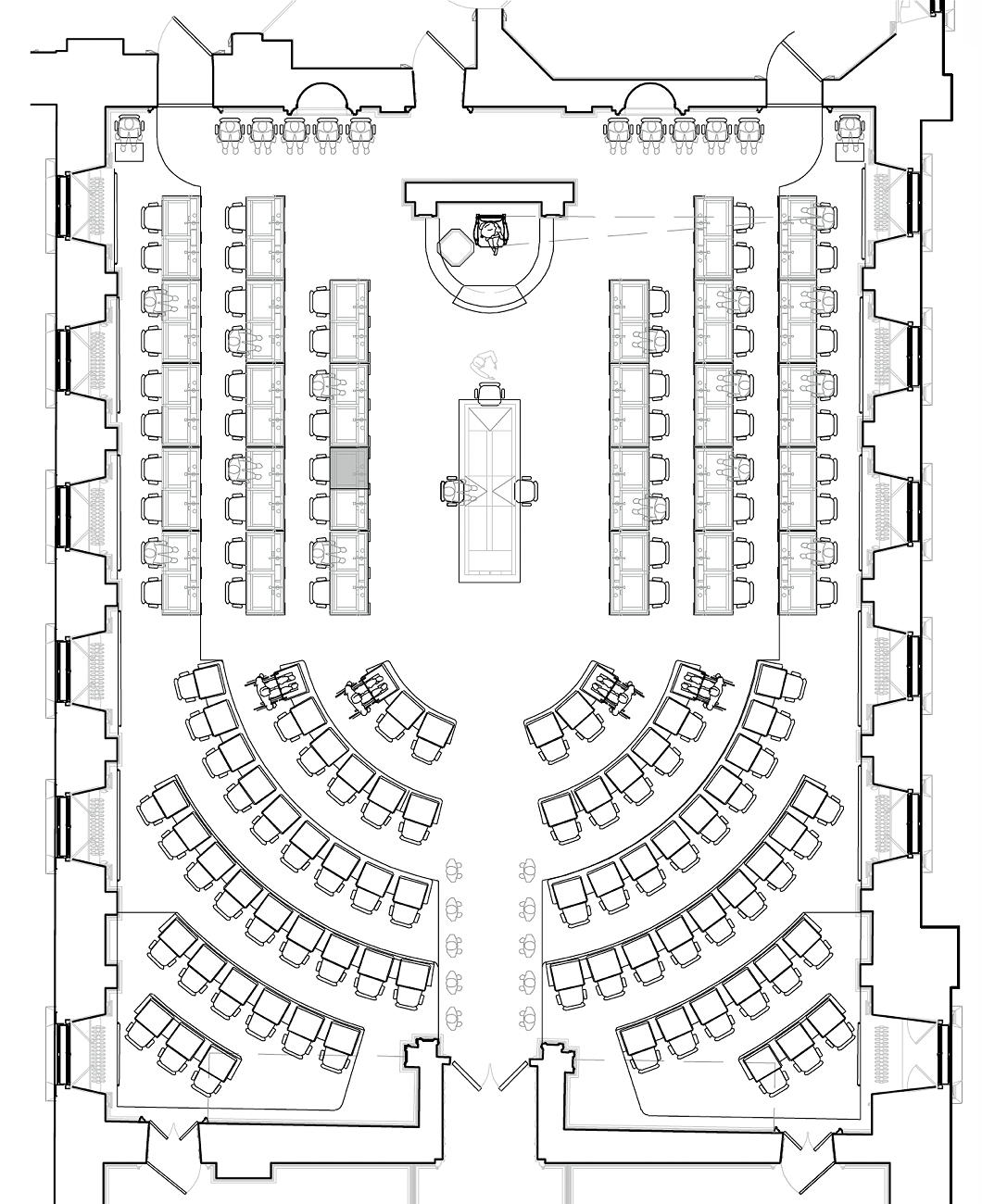

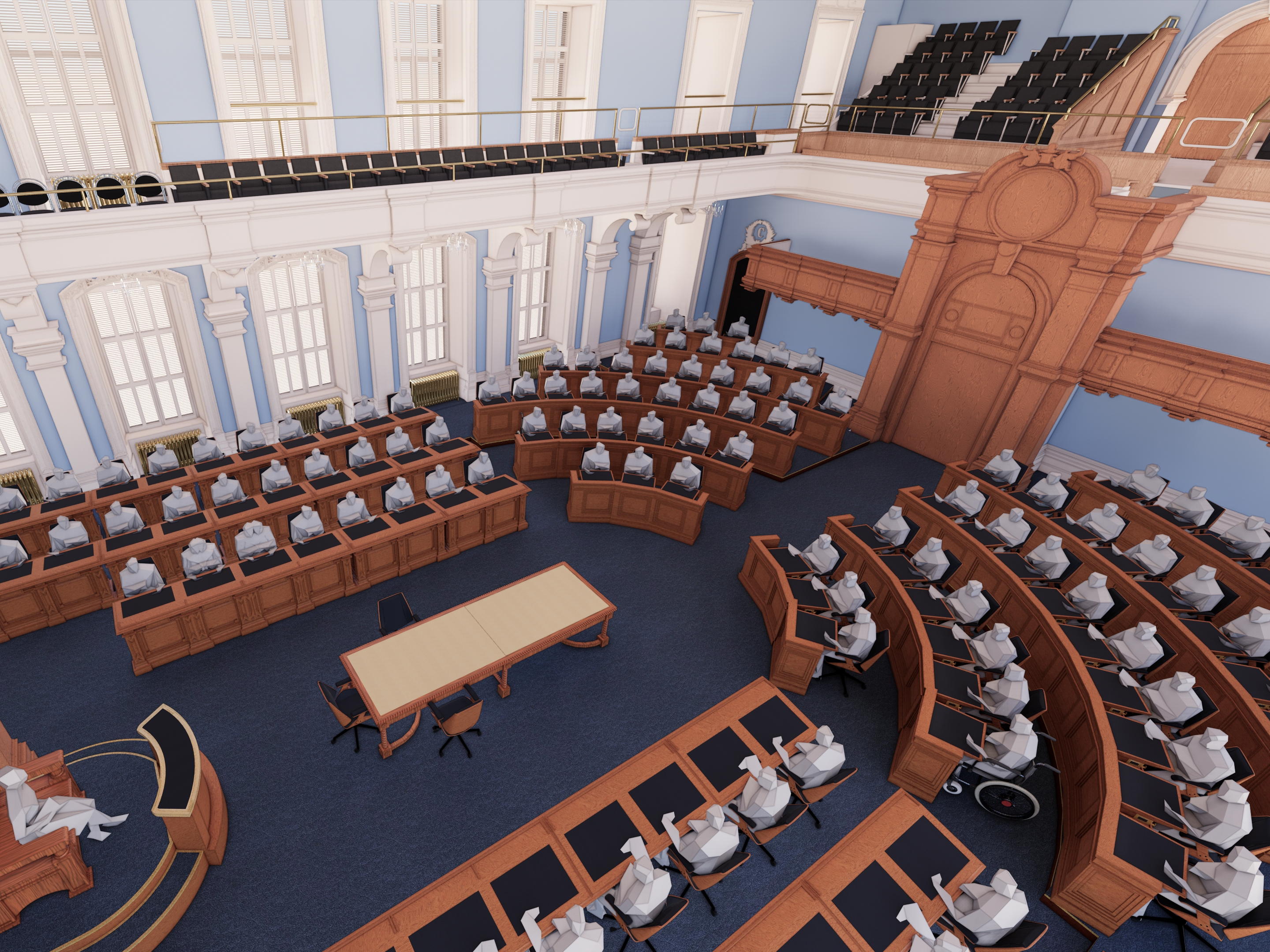

Horseshoe for Quebec’s Salon bleu

Refit will change seating plan in Quebec’s parliament chamber

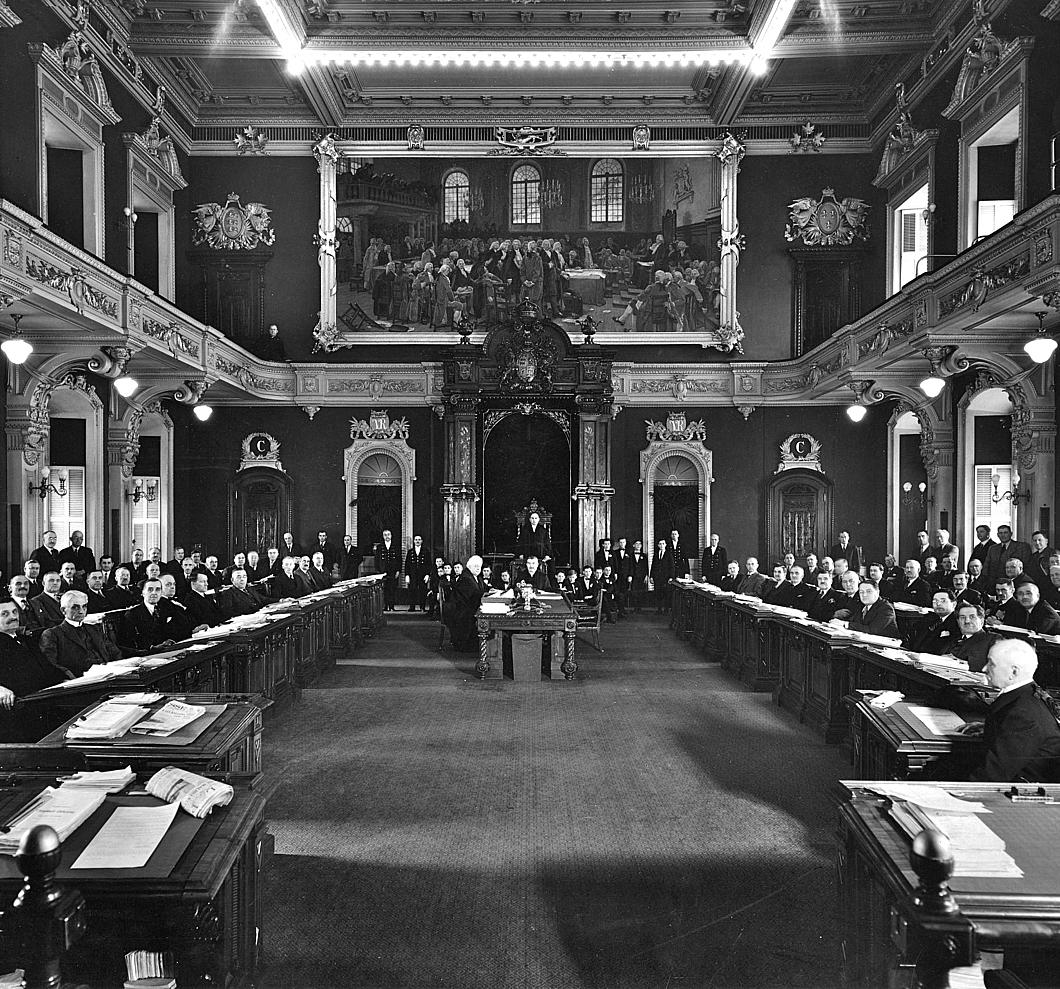

An upcoming renovation to the Hôtel du parlement in Quebec City will also bring a change in the seating plan of the Assembly’s parliamentary chamber. Deputés agreed a moderate alteration to the current Westminster-style seating plan: a horseshoe shape will replace the crowded back two rows of desks with a curved arrangement.

The original clerks’ table designed by the building’s architect, Eugène-Étienne Taché, in 1886 will also be returned to centre-stage in the Salon bleu (formerly the Salon vert) of Quebec’s National Assembly. The room is also, I believe, the only parliamentary chamber to feature in a film by Alfred Hitchcock.

Renovations are scheduled to begin in January of next year, when deputés will start convening in the Salon rouge that formerly housed Quebec’s Legislative Council, abolished in 1968. (Quebec was the last Canadian province to abolish the upper house of its parliament.)

“The Salon bleu has a strong symbolic value for the Quebec nation,” claims Éric Montigny, professor of political science at Laval University (founded 1663).

“We must respect this tradition and evolve in a very, very gradual manner,” Professor Montigny told the Journal de Québec. “A parliament is not trivial.”

The Assembly numbered only sixty-five members when Taché’s edifice was completed in 1886, while today 125 deputés have to fit into the parliamentary chamber.

The new arrangement would make room for as many as 130 legislators, plus the Président in the speaker’s chair. It will also allow for a good number of the historic desks in the chamber to be retained.

Other potential arrangements were considered and rejected, including introducing a half-moon hemicycle akin to Paris, Washington, and other republican legislatures.

Prof Montigny dismissed claims that semicircular arrangements lead to more collaborative dialogue and constructive work between government and opposition parties:

“It’s an argument that is raised regularly, but I don’t know of any studies that will support this theory.”

The most significant change to the chamber in recent years was the removal of the crucifix from above the président’s chair, first installed in 1936 by the giant of Quebec politics, premier Maurice Duplessis.

That crucifix, and its 1982 replacement, were removed in 2019 and are now displayed as historical artefacts in an ancillary part of the parliament building.

[NDLR: I wrote about the crucifix back in 2008.]

The horseshoe seating plan seems a happy compromise: Westminster-style parliaments — even those that are unicameral like Quebec’s — are honest about the antagonism between government and opposition, and the horseshoe preserves the antiphonal arrangement conducive to this, while rounding it off with a curve at the end.

For my part, I will be happy to see the removal of the arbitrary trapezoid of the modern clerks’ table (below) and its replacement by its historic predecessor.

Staats Long Morris

Everyone knows about Gouverneur Morris, scion of one of New York’s great landowning families and given the moniker ‘penman of the Constitution’. As a signer of the Declaration of Independence his half-brother Lewis Morris III was a fellow ‘founding father’. Less well-remembered is his other half-brother Staats Long Morris (1728–1800).

Their father Lewis Morris II was the second lord of Morrisania, the feudal manor that covered most of what is now the South Bronx and has given its name to the smaller eponymous neighbourhood today.

Staats and Gouveneur owe their distinctive Christian names to the family names of their respective mothers.

Lewis II married Katrintje Staats who provided him with four children. After Katrintje died in 1730, Lewis married Sarah Gouverneur, daughter of the Amsterdam-born Isaac Gouverneur. Sarah’s uncle Abraham was Speaker of the General Assembly of the Province of New York, a role Lewis Morris II eventually filled.

Staats was born at Morrisania on 27 August 1728 and studied at Yale College in neighbouring Connecticut as well as serving as a lieutenant in New York’s provincial militia. He switched to the regular forces in 1755 when he obtained a commission as captain in the 50th Regiment of Foot, moving to the 36th in 1756.

Around that time Catherine, Duchess of Gordon, the somewhat eccentric widow of the third duke, was on the lookout for a second husband and Staats — though American, mere gentry, and ten years her junior — met with her approval. They were married in 1756 and Staats moved in to Gordon Castle to live as the Dowager Duchess’s husband.

‘He conducted himself in this new exaltation with so much moderation, affability, and friendship,’ a newspaper reported in 1781, ‘that the family soon forgot the degradation the Duchess had been guilty of by such a connexion, and received her spouse into their perfect favour and esteem.’

With the Duchess’s patronage, Lieutenant-Colonel Staats raised the 89th Regiment of Foot — “Morris’s Highlanders” — from the Scottish counties of Aberdeenshire and Banffshire though she was extremely cross when her new husband’s regiment was despatched to India where it took part in the siege of Pondichery.

In the event, Morris delayed following his regiment to India, leaving England in April 1762 and remaining there only until December 1763. When the young fourth Duke of Gordon came of age the following year, Staats turned his eyes to America and engaged in land speculation there. In 1768 he and the Duchess even went to visit their purchases in the new world, returning to Scotland in the summer of the following year.

With the fourth Duke’s help, and on the eve of the revolutionary stirrings in North America, Staats was elected to the British parliament for the Scottish seat of Elgin Burghs in 1774. He managed to hold on to it for the next ten years. Was this New Yorker the first Yale man to be elected to Parliament? I can’t find any before him, but more thorough research might prove fruitful.

In 1786 he inherited the manor of Morrisania but with the intervening separation between Great Britain and most of her Atlantic colonies General Morris thought it best to sell it on to his brother Gouverneur.

Though he had rejected a future in the world into which he had been born, Staats did return to North America in a professional capacity in 1797 when he was appointed governor of the military garrison at Quebec in what by then was Lower Canada.

Morris died there in January 1800, but his earthly remains were sent back to Britain where he was interred in Westminster Abbey — the only American to receive that honour.

Buchan in Quebec

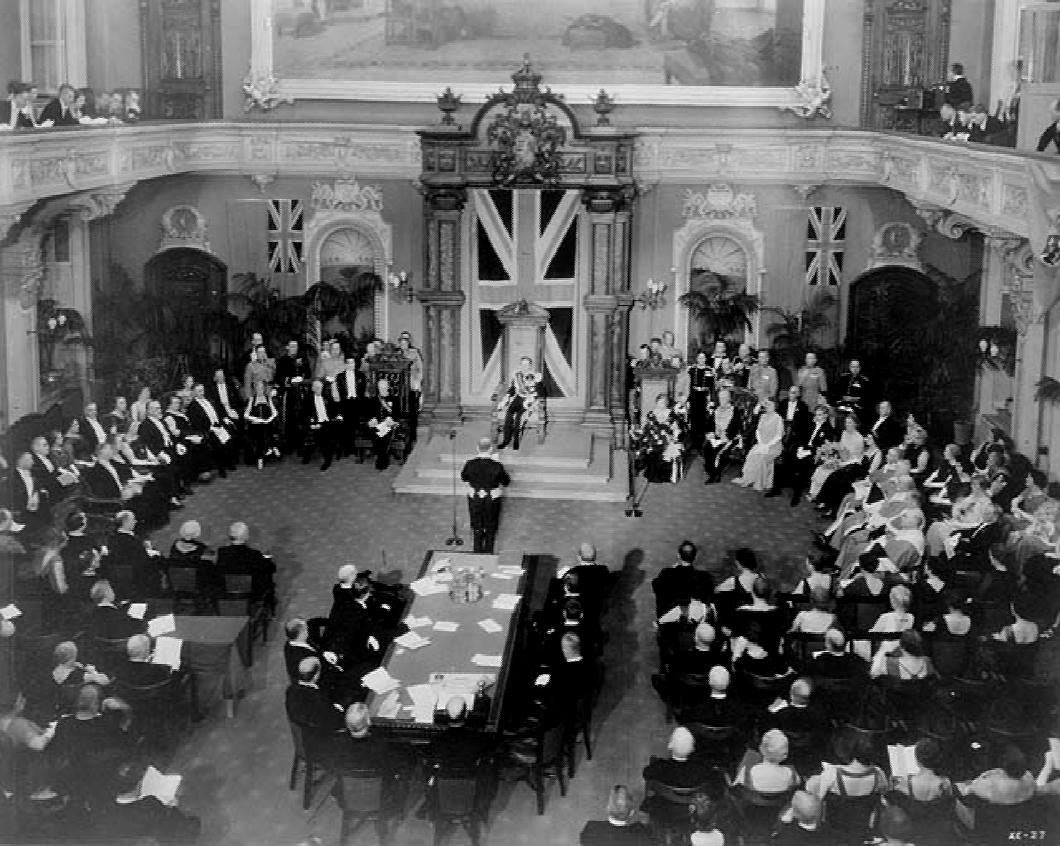

While the Salon bleu in Quebec’s parliament used to be green, the Salon rouge has kept its lordly colour. Conservative Quebec was the last of the Canadian provinces to abolish its unelected upper house which faced the chop in 1968, that year so beloved of duty-shirkers and ne’er-do-wells.

Thirty-three years earlier, the Salon rouge was the scene of a more regal ceremony: the official installation of the Scots writer and statesman John Buchan as Governor General of Canada. Being a Presbyterian with an in-built (but in his case only occasional) tendency to dourness, Buchan wanted to go as an ordinary commoner but the King of Canada insisted on a peerage for his viceregal representative in the dominion.

Thus it was Lord Tweedsmuir who arrived in Quebec in 1935 and was installed as Governor General in the Salon rouge on All Souls’ Day of that year. Above, the Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King gives an address after the swearing-in.

Buchan proved an influential Governor General and helped set the tone of Canada’s monarchy in the aftermath of the 1931 Statue of Westminster that recognised the distinct nature of the Commonwealth realms. He also orchestrated the King’s successful 1939 trip across Canada — which also featured the King and Queen holding court in the Salon rouge of Quebec’s Parliament.

By the time of his death in post in 1940, John Buchan had become His Excellency The Right Honourable The Lord Tweedsmuir GCMG GCVO CH PC. Not a bad end to a good innings.

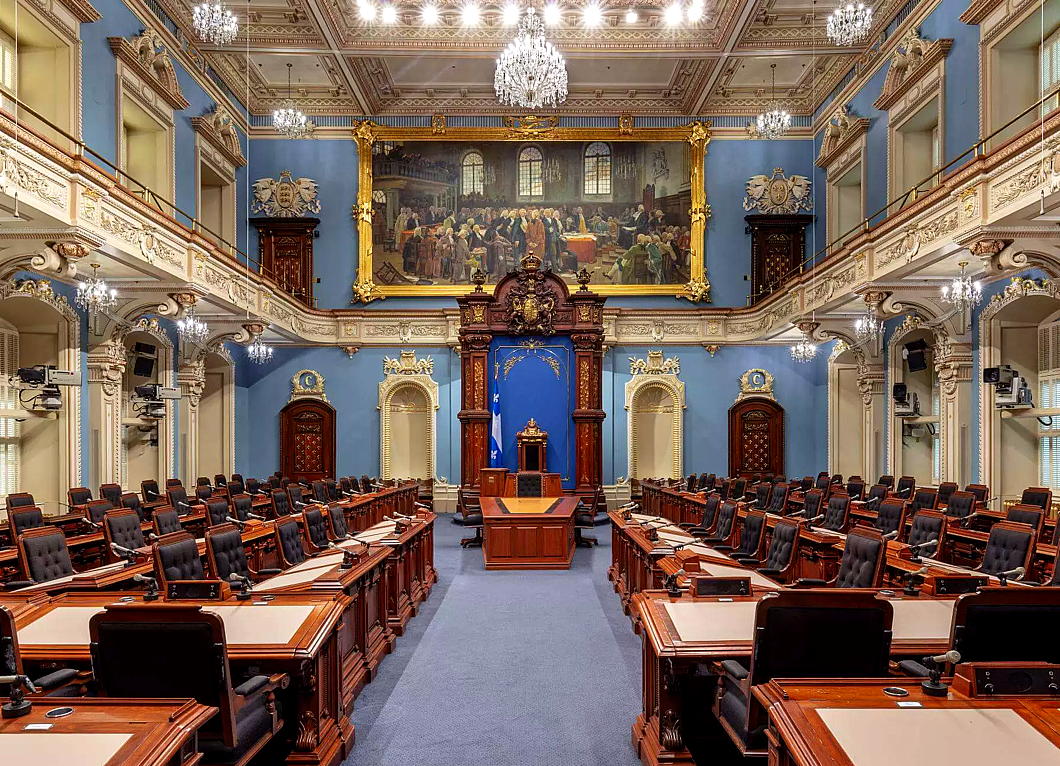

The politics of parliamentary colour

When Quebec’s « Salon bleu » was the « Salon vert »

One Westminster tradition replicated in many times and places across the Commonwealth is a convention of colour: the lower house of a parliament is decorated in green, while the upper chamber is decorated in red. This reflects the green benches of the House of Commons and the red ones of the House of Lords.

Officially the plenary chamber of Quebec’s unicameral parliament is boringly the salle de l’Assemblée nationale but because of the colour of its walls it is more often known as the Salon bleu. One’s never surprised when Quebec bucks a trend or (more specifically) rejects an Anglo convention but it turns out the province’s plenary chamber did in fact used to be green until relatively recently.

When the members of the Legislative Assembly (as it then was) first convened in the Hôtel du Parlement in 1886 the walls were actually white. By the opening of the 1895 session the desks had been reappointed in green, but Le Soleil still made reference to the room as the “chambre blanche”. It was only in 1901 that the room was painted a “soft green” and the carpets and other furnishings changed accordingly. It even made an appearance in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1953 film “I Confess”.

From then the chamber was a Salon vert until 1978, when the decision was taken to begin broadcasting the proceedings of the Assemblée nationale.

The television specialists complained that the dark green of the chamber was not visually conducive to the TV cameras available at the time and, looking at the evidence from the 1977 test session (above), one can see their point. Walls of either beige or blue were the options recommended in an official report, and unsurprisingly the national colour was chosen.

The historian Gaston Deschênes has mentioned the technical requirements of broadcasting also coincided with a desire to break with a “British” tradition. Certainly the government of the day, René Lévesque’s Parti Québécois, didn’t mind the change, while Maurice Bellemare — “the old lion of Quebec politics” and sometime leader of the old Union nationale — was deeply pleased that the chamber adopted the colour of Quebec’s flag.

So the walls were repainted sky blue and the furnishings changed accordingly, resulting in the Salon bleu we know today (below).

A tweet from the Assemblée’s official account shows two photos looking towards the chamber’s entrance from before (above) and after (below) it was made ready for television.

All the same, green is not universal amongst Commonwealth lower (or only) chambers. It’s not even universal in Canada: Manitoba joins Quebec in its azure tones while British Columbia’s is red-dominated.

Quebec was the last of Canada’s provinces to abolish its upper house, the Legislative Council, in 1968 (at the same time the lower house was renamed the National Assembly). The Legislative Council’s former meeting place is, of course, red, and the Salon rouge is used for important occasions like inductions into the Ordre national du Québec or the lying-in-state of the late Jacques Parizeau.

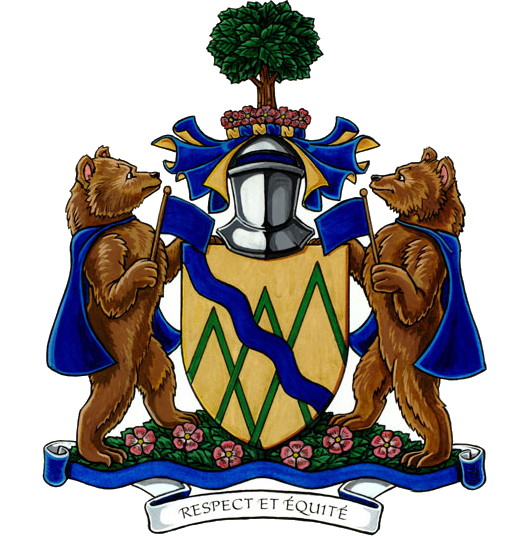

Caped Bear Cubs in Canadian Arms

As my sister was educated (or something to that effect) by Ursulines, a recent addition to Canada’s Public Register of Arms, Flags, and Badges caught my attention. The Queen of Canada granted a coat of arms to the Quebec municipality of Sainte-Angèle-de-Mérici in 2013 (pictured above).

The shield of the arms features three chevronels represent the mountains surrounding the area while their number reminds us that Sainte-Angèle-de-Mérici is a municipality formed from two townships — Cabot and Fleuriault — and the single seigneury of Lepage-et-Thivierge. The wavy blue stripe represents the Mitis River, while gold symbolises the agricultural industry of the Sainte-Angèle-de-Mérici.

The charming aspect are the supporters: two bear cubs. St Angela Merici was the founder of the Ursulines — the Order of St Ursula — and ‘Ursula’ is Latin for ‘little female bear’.

“The bear also symbolizes bravery, thus signifying St. Angela Merici’s martyrdom,” the Canadian Heraldic Authority further explains. “The cloak is one of her traditional attributes. The flags (drapeau in French) honour Angèle Drapeau (1799-1876), the youngest daughter of Seigneur Joseph Drapeau and benefactor of the municipality.”

Protestant King in His Catholic Realm

George VI in Quebec

In the midst of some unrelated research the other day, I came across these photos of George VI on his first visit to Quebec as King in 1939. I think the Parlement du Québec is probably the only Commonwealth legislature to have a crucifix in its plenary chamber (c.f. ‘Christ at the heart of Quebec’, 25 May 2008). No, no, of course the Maltese do as well, in their surprisingly ugly parliament chamber. But Malta is now an island republic, while Quebec retains its monarchy.

In the above picture, the King and Queen of Canada hear a loyal address in the Salle du Conseil législatif of the Hôtel du Parlement in the city of Quebec. Below, the King speaks at a state dinner in the Chateau Frontenac. Seated is Cardinal Villeneuve, the Primat du Canada and Archbishop of Quebec.

The UN at Quebec

IN 1943, THE BRITISH, Canadian, and American governments descended upon the city of Quebec, capital of la vieille province, for an intergovernmental conference to plan the invasion of France — surely one of the greatest military tasks ever undertaken in the modern era. The site proved auspicious due to a peculiar combination of factors: Quebec City enjoys a certain European cachet but with both the geographic safety of North America and the more spacious accommodation usual to that continent. The three governments held a second conference there in 1944, and in 1945 the International Labour Organisation met in the city, followed a few months later by the Food & Agriculture Organisation of the nascent United Nations.

With this track record of indisputable experience, the ville de Québec, lead by its mayor Lucien Borne, put in a bid to be the permanent seat of the United Nations Organisation. (more…)

A Breath of Fresh, Northern Air

The Dorchester Review Proves That Canada is Still Thinking

This summer I received an email from my friend Bruce Patterson, all-around nice guy and Deputy Chief Herald of Canada, informing me of a new historical and literary review just founded called the Dorchester Review. Intrigued, I obtained a copy and was pleasantly enthralled with what I found. The first issue of the Dorchester Review contained a variety of thoughtful articles on fascinating subjects. I spent an entire morning sitting comfortably on a café sofa and imbibing the intelligent and enlightening contents of the magazine.

The editors did issue a brief statement explaining the genesis of their new review. They had me at their Pieperian first sentence: “The Dorchester Review is founded on the belief that leisure is the basis of culture.”

Just as no one can live without pleasure, no civilized life can be sustained without recourse to that tranquillity in which critical articles and book reviews may be profitably enjoyed. The wisdom and perspective that flow from history, biography, and fiction are essential to the good life. It is not merely that “the record of what men have done in the past and how they have done it is the chief positive guide to present action,” as Belloc put it. Action can be dangerous if not preceded by contemplation that begins in recollection.

The endeavour of reviewing books, the editors acknowledge, has too often been reduced either to brief puff-pieces in the Saturday insert of the local paper or more high-minded but uncritical praise of like-minded academics for one another. “There are too few critical reviews published today, particularly in Canada, and almost none translated from francophone journals for English readers.” As someone with a lifelong love of Quebec, I am relieved that finally there is a review in my own language willing to take Quebec seriously.

“At the Review,” the editors continue, “we shall praise the good books and assail the bad.”

They also forthrightly explain their rejection of the narrow nationalist perspective that has been on the ascendant in Canada throughout the past century, especially since the foundation of The Canadian Forum. The Dorchester Review effectively throws Canada’s doors open to a more reasoned understanding of the country’s relationship with Europe (Britain and France particularly), America, the Commonwealth, and the world.

But the Dorchester Review is not a publication just for Canadians. There is a great deal of Canada in it, but also a great deal of the world. The second issue (just printed) features articles with titles such as “Why Marx is Still (Mostly) Wrong”, “1789: The First Counter-Revolutionaries”, “What Sort of Autocrats Were the Popes?”, “Can Vichy France Be Defended?”, and “The Scots Fight Back” (the last in response to an article in the first issue: “How the English Invented the Scots”).

Contributing editor Chris Champion is interviewed by CBC Radio here. A number of the contributors (Conrad Black, Paul Hollander, etc.) readers of The New Criterion will already be familiar with. The latest number also includes a book review by this, your humble and obedient scribe.

Head over to dorchesterreview.ca to find out more or subscribe.

Le drapeau « Jacques Cartier »

To be filed under ‘Flags I Never Knew Existed’: the Québécois heraldist Maurice Brodeur designed a flag commemorating the French explorer Jacques Cartier, founder of Quebec and Canada.

The banner was designed to hang as an ex-voto in the Memorial Basilica of Christ the King in Gaspé, conceived in the 1920’s as an offering of thanks for the four-hundredth anniversary of the claiming of Canada by Cartier.

The Great Depression brought the project to a halt, and the church was finally finished in 1969 as a modernist cathedral in wood — the only wooden cathedral in Catholic North America.

Was the flag ever actually executed? I don’t know, but I doubt it.

Les fondements de notre civilisation occidentale

« Les fondements de notre civilisation occidentale sont chrétiens ; le respect du christianisme est une condition sine qua non d’une droite qui veut conserver non seulement la prospérité économique, mais ce qui est au fondement de toute prospérité durable : le souci du bien commun, le respect de la loi naturelle, le sens de la justice. »

The latest issue of Égards, the premier journal of traditional conservatism in Quebec, contains an interesting analysis of the current situation faced by the various streams of the centre-droit spectrum in the province. I am, however, very much against the perpetual organisation-founding that goes on in political circles. There seems to be a belief that, when in doubt, start a new organisation, but this is precisely what the author, M. Décarie, proposes.

Interesting Things Elsewhere

This determined Celt is gunning for Thabo

Kevin Bloom | The Daily Maverick

Ireland’s  Paul O’Sullivan took over as head of security at South Africa’s airport authority in 2001, and discovered something was wrong from the start: why didn’t the policeman on duty want to take a statement about the attempted theft of his baggage? Since then, his life has been a series of bizarre events leading him ever deeper into the most complex criminal network of the post-apartheid era, including the recent the trial and conviction of former national police chief Jackie Selebi. But O’Sullivan’s determined quest to expose crookedness isn’t over yet, and he now has former president Thabo Mbeki in his sights. read more

Paul O’Sullivan took over as head of security at South Africa’s airport authority in 2001, and discovered something was wrong from the start: why didn’t the policeman on duty want to take a statement about the attempted theft of his baggage? Since then, his life has been a series of bizarre events leading him ever deeper into the most complex criminal network of the post-apartheid era, including the recent the trial and conviction of former national police chief Jackie Selebi. But O’Sullivan’s determined quest to expose crookedness isn’t over yet, and he now has former president Thabo Mbeki in his sights. read more

The apparatus of state will simply ignore the government

‘Inspector Gadget’ | Police Inspector Blog

Police across England were told by the responsible minister of the democratically elected government that they must not chase performance targets any longer. “I can also announce today that I am also scrapping the confidence target,” said the Home Secretary, Theresa May, “and the policing pledge with immediate effect”. But the ‘senior management team’ of the West Yorkshire Police have stated they will go on no matter what the government says. read more

Has Christian Democracy reached a dead end?

Jan-Werner Mueller | Guardian.co.uk

The commentator completes a brief survey of the struggles of Christian Democracy in Germany and Europe today. The French leader Georges Bidault claimed that Christian Democracy meant “to govern in the centre, and pursue, by the methods of the right, the policies of the left”. But Christian Democracy’s brief French moment in the 1950s didn’t survive the return of de Gaulle, and Christian Democratic parties on the continent today face an existential crisis. read more

Also: Monsignor Ignacio Barreiro’s talk at the Roman Forum’s 2010 Summer Symposium, entitled The Problem of Christian Democracy will be made available online in audio form sometime in the coming months.

Deep in Shanxi, the most Catholic village in China

Anthony E. Clark | Ignatius Insight

Church after church dot the landscape and high steeples rise above small villages as they do in southern France. Passing through a narrow side road one arrives and is welcomed by three great statues at the village entrance: St. Peter holding his keys is flanked by Saints Simon and Paul. Thirty minutes before Mass the village loudspeakers, once airing the revolutionary voice of Mao and Party slogans, now broadcasts the rosary. Welcome to Liuhecun, the most Catholic village in China. read more

Look for me in the Cotswolds.

Dino Marcantonio

The apologists for modernist architecture have tried for a century to gain public acceptance of and appreciation for their horrors. While the elites have almost overwhelmingly been converted, the general populace around the world still sees that the Emperor has no clothes, and almost always prefers architecture that reflects the tried and true, the local and the natural. Alain de Botton, the Swiss essayist, ‘pop philosopher’, and former ‘writer-in-residence’ at Heathrow Airport, is the latest to give it a go, this time in the pages of the modernist Architectural Record. Dino Marcantonio provides a most useful fisking. read more

Canada is a French country

Andrew Coyne | Maclean’s

At the recent Canada Day celebrations on Parliament Hill, Canadian PM Stephen Harper spoke of “the steadfast determination and continental ambition of our French pioneers, who were the first to call themselves ‘Canadians.’” At other times he has spoken of Canada as having been “born in French,” of French as “Canada’s first language,” and, most famously, of Quebec City as “Canada’s first city,” its founding in 1608 as marking “the founding of the Canadian state.” While the sentiment may seen anodyne, moreover, the implications are radical. read more

Tintin à Quebec

Tintinophilia and its allied science of Tintintology can almost seem like a cult sometime, with Moulinsart, the commercial wing of the Hergé Foundation, acting feverishly to quell any and all unauthorised outbreaks of Tintin resurrection. Their assiduity notwithstanding, Tintin pastiches are fairly common (though illegal) and vary in nature from respectful admiration to downright mockery. The Quebecois cartoonist Yves Rodier is one of the foremost pasticheurs of the famous Belgian boy reporter, and produced this cover (above) of a non-existant Tintin book set in the beautiful capital city of Canada’s French province.

While Tintin did visit Scotland in The Black Isle, I’d love to see a Tintin in Edinburgh book, and even more so Tintin in the Cape.

La Grande Séduction

This is a perfectly charming film. “La Grande Séduction” comically celebrates the dignity of work and the assault on the human character that inevitably results from reliance upon government welfare for survival. The inhabitants of the small fishing village of Ste-Marie-La-Mauderne have refused to abandon their homes after the collapse of fishing, but lack the resident doctor a potential investor requires in order to build his factory in the town. “La Grande Séduction” (released in Anglophone cinemas as “Seducing Dr. Lewis”) depicts the efforts of prominent townsfolk to unite and persuade the arrogant city-slicker Dr. Lewis to sign up as doctor for their little corner of the world.

Fans of “Local Hero” or “Waking Ned Devine” will find the theme familiar, but with a remote corner of maritime Quebec substituting for the Celtic hinterlands of the British Isles. If anything, the film allows the viewer an opportunity to hear that charming Québécois back-country accent. There are also elements that will grate somewhat the prudish tendencies of Anglos like us, but one must make allowances for the Latin temperament that survives in la Nouvelle-France and the other Romance realms.

Overall, a celebration of place, work, and community, and an interesting exploration of the conflict between artificiality and authenticity.

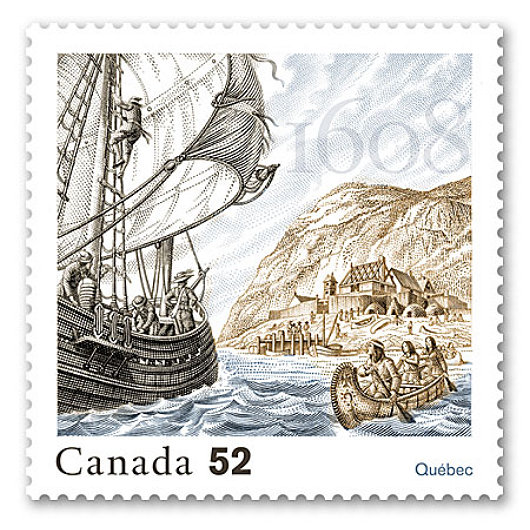

Quebec Stamp

This stamp was designed by Jorge Peral, the artistic director of the Canadian Bank Note Company, for Canada Post to commemorate the four-hundredth anniversary of the foundation of Quebec.

The arms of the Hon. Paul Comtois

Our friend Mr. Bruce Patterson, who is St-Laurent Herald up in the Canadian Heraldic Authority, was kind enough to send along this rendering of the arms of the Hon. Paul Comtois from Beddoe’s Canadian Heraldry. As Bruce points out, the garbs probably refer to Comtois’s agricultural background, and the miner’s pick in the crest alludes to his ministerial portfolio. The motto is “Be frank & honest”.

Paul Comtois of Québec

Farmer, Politician, Hero, Saint

FROM TIME TO TIME there are men in history whose heroism runs so counter to the spirit of the age that the arbiters of passing fashion must simply ignore him rather than run the risk of acknowledging his embarrassing greatness and goodness. God has graced the New World with many of His saints, some of whom — Rose of Lima, Martin de Porres, Mother Seton — have already been raised to the altar, others — Fulton Sheen, Fr. Solanus Casey — are certainly on their way. Yet more remain unsung and almost forgotten: Paul Comtois (1895–1966), Lieutenant-Governor of Québec until his heroic death, is just one of these saints.

A New Speaker in Quebec

Opposition parties unite to elect new President of the Assembly

François Gendron, the longest-serving member of Quebec’s National Assembly, has been elected Speaker against the will of the province’s prime minister, Jean Charest. The ADQ (conservative, autonomist) and PQ (social-democratic, pro-independence) are opposition parties but combined have more seats than the Libéral (center-left/center-right) minority government Mr. Charest leads. Action democratique du Québec and the Parti Québécois united to select Mr. Gendron without consulting Mr. Charest, which the premier described as a “breach of confidence” that was the result of “subterfuge”. The vote took place by secret ballot, and it was only in the hours before that the opposition parties withdrew their respective candidates in favour of a united ticket for Gendron.

Charles & Zita

October 21 was chosen as the Feast of the Blessed Emperor Charles not because it is the date of his death — which is 1 April 1922 — but rather to commemorate the marriage (photo, below) between Archduke Charles of Austria (as he was then) and Princess Zita of Bourbon-Parma in 1911. While Charles died a mere thirty-four years of age, Zita lived on to ninety-six before passing away in 1989 (when I myself was four).

Not very long ago I was in Quebec City, which was where the Empress Zita and the Imperial Family spent their exile during the Second World War. The Hapsburgs, dispossessed first by the Socialists and then by the Nazis, were then so poor they had to collect dandelions from which to make a soup, but they took poverty in their stride. Passing a grassy bit near the Chateau Frontenac, I wondered “Did Crown Prince Otto once pluck weeds from this plot to feed his hungry mother and siblings?”

Also in that ancient Canadian city is La Citadelle, that great hunk of stone and earthworks, perhaps the oldest operational military installation in the New World. There we were lucky enough to be granted access to the tomb of the greatest Canadian, Major General the Rt. Hon. Georges-Philéas Vanier, Governor-General of Canada from 1959 until his death in 1967. General Vanier and his wife had such a reputation for Christian charity and piety that the Vatican is collecting evidence towards their eventual recognition as saints. Their son is Jean Vanier, the founder of the famous l’Arche communities that care for the handicapped and the disabled. I wonder if the Hapsburgs and the Vaniers ever crossed paths in wartime Quebec…

pray for us!

Horse & Hound in Montreal

A splendid afternoon is the best way to describe it. Last Sunday up in St-Augustin-de-Mirabel it was the annual hunter trials of the Montreal Hunt Club – the oldest hunt in the New World. Club treasurer Annette Laroche suggested swinging by the Club sometime and as it happens a good friend had just moved to Montreal. So when Raymond Côté (seen in the previous post jumping on the beautiful white mare Frimousse) sent an invite to the hunter trials, I knew it’d be foolish not to take the opportunity to visit the beautiful land of Quebec for the first time in many years.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories