Patrick Leigh Fermor

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

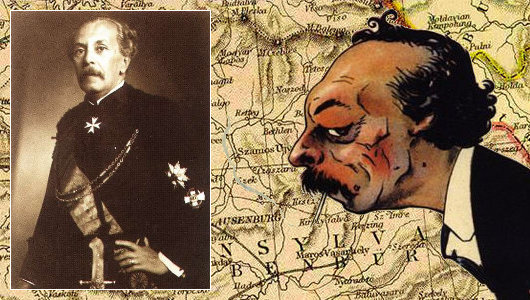

‘The Tolstoy of Transylvania’

In his column in the Daily Telegraph, former editor Charles Moore praises Miklos Banffy as ‘the Tolstoy of Transylvania’. Ardent Banffyites like myself are always pleased when the Hungarian novelist gets attention in the English-speaking world, which happens all too rarely. I can’t remember how on earth I stumbled upon the works of Banffy, probably through reading the Hungarian Quarterly, a publication that — covering art, literature, history, politics, science, and more — is admirably polymathic in our age in which the specialist niche is worshipped.

To put it simply, Banffy is a must-read. If you love Paddy Leigh Fermor’s telling of his youthful walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople (the third and final installation of which we still await), then Miklos Banffy will be right up your alley. Start with his Transylvanian trilogy — They Were Counted, They Were Found Wanting, and They Were Divided.

The story follows two cousins, the earnest Balint Abady and the dissolute László Gyeroffy, Hungarian aristocrats in Transylvania, and the varying paths they take in the final years of European civilization. The novels “are full of love for the way of life destroyed by the First World War,” Charles Moore points out, “but without illusion about its deficiencies.”

Three volumes of nearly one-and-a-half thousand pages put together, they make for deeply, deeply rewarding reading, transporting you to the world that ended with the crack of an assassin’s bullet in Sarajevo, 1914.

After finishing his trilogy, Banffy’s autobiographical The Phoenix Land is worthwhile; some of the real events depicted shadow those in the fictional novels. As previously mentioned, it contains a description of the last Hapsburg coronation (that of Blessed Charles) and numerous amusing tales.

After that, I’m afraid you will have to learn Hungarian, which I have neglected to do, as no more of this author’s oeuvre has yet been translated into English.

Praga Caput Regni

Prague: Capital & Head of the Bohemian Realm

Prague is traditionally known as “Praga Caput Regni” — the capital of the realm, or indeed the head of the Bohemian body. Changing times and a different form of government mean that the arms of this ancient city now bear the motto “Praga Caput Rei Publicae” instead. The photographer Libor Sváček was born in the be-castled city of Krummau, and has a splendid book of photographs of that town, but here are a number of his photographs of Prague, which splendidly exhibit the Old Town at its most beautiful. (more…)

‘The man who walked’

The Daily Telegraph — 6 September 2008

At 18 he left home to walk the length of Europe; at 25, as an SOE agent, he kidnapped the German commander of Crete; now at 93, Patrick Leigh Fermor, arguably the greatest living travel writer, is publishing the nearest he may come to an autobiography – and finally learning to type. William Dalrymple meets him at home in Greece

‘You’ve got to bellow a bit,’ Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor said, inclining his face in my direction, and cupping his ear. ‘He’s become an economist? Well, thank God for that. I thought you said he’d become a Communist.’

He took a swig of retsina and returned to his lemon chicken.

‘I’m deaf,’ he continued. ‘That’s the awful truth. That’s why I’m leaning towards you in this rather eerie fashion. I do have a hearing aid, but when I go swimming I always forget about it until I’m two strokes out, and then it starts singing at me. I get out and suck it, and with luck all is well. But both of them have gone now, and that’s one reason why I am off to London next week. Glasses, too. Running out of those very quickly. Occasionally, the one that is lost is found, but their numbers slowly diminish…’

He trailed off. ‘The amount that can go wrong at this age – you’ve no idea. This year I’ve acquired something called tunnel vision. Very odd, and sometimes quite interesting. When I look at someone I can see four eyes, one of them huge and stuck to the side of the mouth. Everyone starts looking a bit like a Picasso painting.’

He paused and considered for a moment, as if confronted by the condition for the first time. ‘And, to be honest, my memory is not in very good shape either. Anything like a date or a proper name just takes wing, and quite often never comes back. Winston Churchill – couldn’t remember his name last week.

‘Even swimming is a bit of a trial now,’ he continued, ‘thanks to this bloody clock thing they’ve put in me – what d’they call it? A pacemaker. It doesn’t mind the swimming. But it doesn’t like the steps on the way down. Terrific nuisance.’

We were sitting eating supper in the moonlight in the arcaded L-shaped cloister that forms the core of Leigh Fermor’s beautiful house in Mani in southern Greece. Since the death of his beloved wife Joan in 2003, Leigh Fermor, known to everyone as Leigh Fermor, has lived here alone in his own Elysium with only an ever-growing clowder of darting, mewing, paw-licking cats for company. He is cooked for and looked after by his housekeeper, Elpida, the daughter of the inn-keeper who was his original landlord when he came to Mani for the first time in 1962.

It is the most perfect writer’s house imaginable, designed and partially built by Leigh Fermor himself in an old olive grove overlooking a secluded Mediterranean bay. It is easy to see why, despite growing visibly frailer, he would never want to leave. Buttressed by the old retaining walls of the olive terraces, the whitewashed rooms are cool and airy and lined with books; old copies of the Times Literary Supplement and the New York Review of Books lie scattered around on tables between Attic vases, Indian sculptures and bottles of local ouzo.

A study filled with reference books and old photographs lies across a shady courtyard. There are cicadas grinding in the cypresses, and a wonderful view of the peaks of the Taygetus falling down to the blue waters of the Aegean, which are so clear it is said that in some places you can still see the wrecks of Ottoman galleys lying on the seabed far below.

There is a warm smell of wild rosemary and cypress resin in the air; and from below comes the crash of the sea on the pebbles of the foreshore. Yet there is something unmistakably melancholy in the air: a great traveller even partially immobilised is as sad a sight as an artist with failing vision or a composer grown hard of hearing.

I had driven down from Athens that morning, through slopes of olives charred and blackened by last year’s forest fires. I arrived at Kardamyli late in the evening. Although the area is now almost metropolitan in feel compared to what it was when Leigh Fermor moved here in the 1960s (at that time he had to move the honey-coloured Taygetus stone for his house to its site by mule as there was no road) it still feels wonderfully remote and almost untouched by the modern world.

When Leigh Fermor first arrived in Mani in 1962 he was known principally as a dashing commando. At the age of 25, as a young agent of Special Operations Executive (SOE), he had kidnapped the German commander in Crete, General Kreipe, and returned home to a Distinguished Service Order and movie version of his exploits, Ill Met by Moonlight (1957) with Dirk Bogarde playing him as a handsome black-shirted guerrilla.

It was in this house that Leigh Fermor made the startling transformation – unique in his generation – from war hero to literary genius. To meet, Leigh Fermor may still have the speech patterns and formal manners of a British officer of a previous generation; but on the page he is a soaring prose virtuoso with hardly a single living equal.

It was here in the isolation and beauty of Kardamyli that Leigh Fermor developed his sublime prose style, and here that he wrote most of the books that have made him widely regarded as the world’s greatest travel writer, as well as arguably our finest living prose-poet. While his densely literary and cadent prose style is beyond imitation, his books have become sacred texts for several generations of British writers of non-fiction, including Bruce Chatwin, Colin Thubron, Philip Marsden, Nicholas Crane and Rory Stewart, all of whom have been inspired by the persona he created of the bookish wanderer: the footloose scholar in the wilds, scrambling through remote mountains, a knapsack full of books on his shoulder.

A Morning’s Journey

I crossed the Harlem River into Manhattan today just as Patrick Leigh Fermor traversed the Danube in his brilliant book, A Time of Gifts, which has immediately become one of my favorite reads of all time. Settling into my seat on the train yesterday, I opened my knapsack to utter shock and surprise—I had left my reading at home. The Leigh Fermor and P.G.W.’s Cocktail Time were resting somewhere in my bedchamber while I stared into the compartment of my bag, bare but for a photocopied page from the Art Newspaper and two (already-read) issues of the Hungarian Quarterly. These are the times that try men’s souls. Getting out of the city late in the evening proved even harder, as the bridge carrying the railway over the river was actually up for once (“First time in my life, folks,” the conductor informed us), leaving a steady backlog of trains awaiting their northerly destinations.

But this morning there were no bridge-raising complications, and the sky was a delightful, clear blue (soon to change) as we entered Manhattan. Thankfully, I had my two books; a bit of Wodehouse while waiting in Bronxville station and then Paddy Leigh Fermor on the train. After crossing the river, the train stops at 125th Street (Harlem) before submerging at 96th, taking the passenger down to Grand Central, that well-kept remnant on 42nd Street, reminding us that we too were once civilized. There, after taking a stroll through the market (Nürnburger sausage! Kaiser ham! Norwegian salmon!) you switch to the subway and hop down just one express stop on the 5 train.

Just half a dozen steps after emerging from Union Square station I saw a speck of white fall from the sky, and then another, and another. So it began: the first snowfall of the year. And, I might add, a New York record for the latest snowfall. (January 10th? No, there was no white Christmas for us this year). Two children on the swings in the playground ecstatically proclaimed their approval at the opening of the heavens. Wandering through the farmer’s market in the square, I picked up an herb focaccia bread I thought might be particularly enjoyable, and it complimented the exceptionally tasty Tuscan vegetable soup I had for lunch. The snowflakes swirled above the square and fell down on all the market-goers and the folks walking on Broadway as I marched up to work. And yet, how fleeting! In the few steps from the front door to the elevator, the white snow had already melted and merged into the green of my loden coat. Very well, Mother Nature. Very well.

Christmas Book List

Mr. and Mrs. Peperium over at Patum Peperium asked a few of their genial friends to come up with a Christmas book list, and we were more than happy to oblige. Interestingly enough, the only overlap was Guy Stair Sainty’s giant two-volume opus, which was both on my list and on Fr. M.’s list. I have reproduced my list below for your perusal.

Well, first up, the books you can’t even get yet, not because they’re out of print but, rather, because they’re not exactly in print yet.

Well, first up, the books you can’t even get yet, not because they’re out of print but, rather, because they’re not exactly in print yet.

The Dangerous Book for Boys by Conn and Hal Iggulden has proved a roaring success amongst discriminating readers in the British Isles. The nifty book is basically a handbook for life, describing in detail how to win at conkers and learn the rules of cricket as well as providing information about major battles of history, NATO’s phonetic alphabet, the golden age of piracy, and that trickiest of all subjects:girls. The book’s out in Britain, Australia, and New Zealand, we North Americans will have to wait until May of next year.

Another book the Brits have already is Michael Burleigh’s Sacred Causes: The Clash of Religion and Politics from the Great War to the War on Terror, the sequel to Burleigh’s brilliant Earthly Powers: The Clash of Religion and Politics in Europe from the French Revolution to the Great War. In the first book, Burleigh brilliantly outlined the “long nineteenth century” as historians call it, depicting in detail the interplay between faith, reason, and power on the Mother Continent. Sacred Causes promises to bring us from the First World War all the way to the current so-called “War on Terror”, and we expect it will be done with the same precise, detailed, though occasionally light-hearted spirit which Burleigh has mastered. The book will be available on these verdant shores from March of next year.

While we’re traveling across the Atlantic, why not explore the British roots of our American society? In America’s British Culture, the late great Russell Kirk explores the Britannic foundations of the core of American culture and civilization. The book’s probably out of print, but can nonetheless be found here and there, and if not to purchase then there’s always the local library to try.

Far more perilous than a voyage cross the Atlantic is that most worrisome, tiresome, and pedantic of journeys: crossing the channel. To Belgium, or perhaps we should say “Belgium”, for after reading Flemish patriot Paul Belien’s A Throne in Brussels: Britain, the Saxe-Coburgs and the Belgianisation of Europe you will find the mere concept of “Belgium” repugnant. I picked up a copy of A Throne in Brussels and decided to give it a whirl despite finding the book’s title mostly uninteresting. After reading it, I also found the subtitle a little misleading. What Belien actually gives us is an overview of the history of “Belgium” which is both succinct and thorough, mostly focusing on the Belgian monarchy and its deep influence on the formation of this “nation” half-French and half-Dutch. It makes for a fascinating read of disgrace and debauchery as we’re told of the disgusting actions of, firstly the various kings of Belgium from the creation of the country ex nihilo in 1830, and then of astonishing Belgian cowardice and collaboration in the First and Second World Wars. However all this pales in comparison to the most telling, and the most disturbing, part of the book which tells us about modern, post-war Belgium. I will not reveal it’s contents but is truly, truly frightening. The point Belien posits as the crux of the book is this: I’ve told you about Belgium. Recall that the Eurocrats and their enthusiasts extol Belgium as the model for European unity; a single state in which communities of different blood and language live together in supposed harmony. If what I’ve written is true, then be afraid: be very afraid. And you will be.

Moving across the Continent, we stumble upon dear old darling Austria. The late Gordon Brook Shepherd was a devoted admirer of the Austrian people and nation, and this is exhibited in a number of the fine, well-crafted books he wrote. The Last Hapsburg is a very good biography of the Blessed Emperor Charles of Austria-Hungary, the last to rule over that many-peopled realm. It reads as a chronicle of simultaneous hope and decline, and the chapters detailing the Emperor’s two attempts to regain his Hungarian throne are action-packed and read like a spy thriller. Prelude to Infamy, meanwhile, deals with that last great figure of Austrian tradition and reaction, Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss. Brook Shepherd gives a splendid overview of Dollfuss’s early life and upbringing, his rise to power, and his eventual downfall at the hands of Hitler’s henchmen. Both these books are well worth reading, but I am also intrigued by the title alone of Brook Shepherd’s biography Between Two Flags: The Life of Baron Sir Rudolf von Slatin Pasha, GCVO, KCMG, CB, on which I have not yet been able to lay my hands.

Travelling deep within Europa’s belly are Patrick Leigh Fermor’s chronicles of his journey through Ruritania at the young age of twenty-two in the period between the wars when a great deal of the old order still remained. This meandering tramping trip, from London to Constantinople, is retold to us in Sir Patrick’s A Time of Gifts, considered a classic in the travel genre, and Between the Woods and the Water.

On his journey, Fermor came across a number of Europe’s aristocrats, nobility, and titled gentry. No doubt many-well, all really-of the honours and orders which bedecked their chests can be found in Guy Stair Sainty’s brand spanking new World Orders of Knighthood & Merit, out this year from Burke’s Peerage. The two volumes weigh in at twenty pounds imperial, containing two thousand pages and yours for a mere $375.

Cheaper, smaller, and infinitely more full of vim and moxie, however, is the delightful little picture book Simple Heraldry Cheerfully Illustrated by Sir Iain Moncrieffe of That Ilk, with truly cheerful illustrations by Don Pottinger. Both Moncreiffe and Pottinger served Her Majesty in the Court of Lord Lyon, Scotland’s heraldic authority, and the book is chock-full of delightful little explanations of the various aspects of heraldry, simplified and in digestible form.

But rememeber man that thou art dust and unto dust thou shalt return. If you’re lucky, that dust will be guarding the covers of the splendid Very Best of the Daily Telegraph’s Books of Obituaries which contains myriad tales of those individuals whose lives have been compacted onto the obituary page of Great Britain’s quality daily. Even more interesting is the more specific Daily Telegraph Book of Military Obituaries, containing various anecdotes of mess, ball, parade ground, and battlefield. How sad are the days when the only place one reads of class, dignity, and wit are the obituary pages! Or, as a friend puts it rather more alarmingly: every day more and more war veterans die off, while more and more products of government schools are unleashed into the world.

Yet our end ought to be a cheerful one, so catch up with that Grand Old Man who has since gone to join the Choir Invisible. The brilliant writings of Peter Simple are collected in a number of different volumes, most notably Peter Simple’s Century, which I warmly encourage the reader to purchase at the nearest opportunity. Better yet, make it two and forward one to me.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

- American Exuberant February 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories