London

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Commons in the Lords

IT WAS THE NIGHT of 10 May 1941. For nine solid months the Luftwaffe had thrown everything it had at the people of London, as Hitler hoped to bomb the English into despair and surrender. By early May, the Nazis realised the campaign had failed, and resources had to be directed elsewhere. The Blitz had to end, but on its final night, it hit one of its most precious targets. Twelve German bombs hit the Palace of Westminster that night, with an incendiary striking a direct hit at the House of Commons. The locus of Britain’s parliamentary democracy was consumed by flame and completely destroyed. (more…)

A Pell Sighting

…and sundry other occurences

Outside of Rome, you don’t run into cardinals all that often, but last Saturday I caught sight of one of the most popular clerics in the Catholic Church: Australia’s Cardinal Pell. The occasion was the Cardinal’s reception into the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of St George, which took place in the Little Oratory. His Royal Highness the Duke of Noto presided over the investiture, and if you squint your eyes enough you can make out a profile shot of Young Cusack in the background of the photo of the Duke (below). In addition to the Cardinal Archbishop of Sydney’s being made a Bailiff Grand Cross of Justice, six others were invested as members of the Constantinian Order, including His Excellency Don Antonio da Silva Coelho, the Ambassador of the Order of Malta to the Republic of Peru. For more info, see the Order’s notice on the event. (more…)

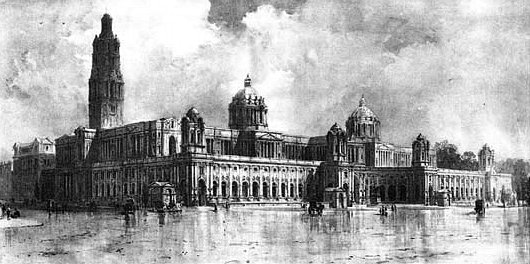

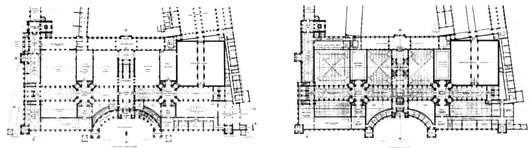

The South Kensington Museum

ANOTHER unbuilt project: this time a plan for completing the South Kensington Museum (or the Victoria & Albert as it’s now called) in the part of London which has become known as ‘Albertopolis’. The museum grew incrementally from its first foundation as the Museum of Manufactures after Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition of 1851.  The first design for the museum at its current site was by Gottfried Semper, but the plan was rejected as being too expensive. And so over the years the facilities grew incrementally and according to to haphazard plans. In the 1890s, eight architects were invited to submit proposals for a grand scheme completing the site under a unified architectural plan.

The first design for the museum at its current site was by Gottfried Semper, but the plan was rejected as being too expensive. And so over the years the facilities grew incrementally and according to to haphazard plans. In the 1890s, eight architects were invited to submit proposals for a grand scheme completing the site under a unified architectural plan.

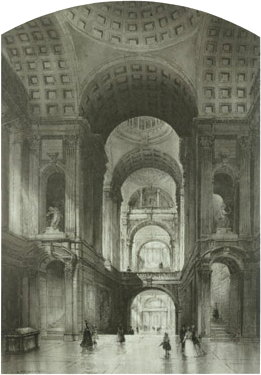

The judges cited this plan, by John Belcher, as the most original of the eight submissions. It’s a splendid composition in high Edwardian neo-baroque. The duality of the main domes is a particular confident touch, and harks back to Greenwich. Belcher’s baroque conception was not just an external factor: his interiors featured vast, sweeping spaces that would have been impressively monumental and reflecting the power and influence of the British Empire at its presumed cultural zenith.

“Although unsuccesful in the competition,” writes Iain Boyd Whyte of Edinburgh University, “this project attracted considerable praise in the professional journals for the plasticity of the main street facade and for its grand, Michelangelesque domes.” While the judges appreciated Belcher’s design, they worried about the cost of its execution, and awarded first prize to Aston Webb instead. His scheme was inaugurated in 1899 by the Queen-Empress, who renamed the institution ‘the Victoria & Albert Museum’ simultaneously.

I wonder if Belcher’s design would have gone better with the neighbouring Brompton Oratory, or if the Oratory benefits from having the V&A in a differing, brick-based style.

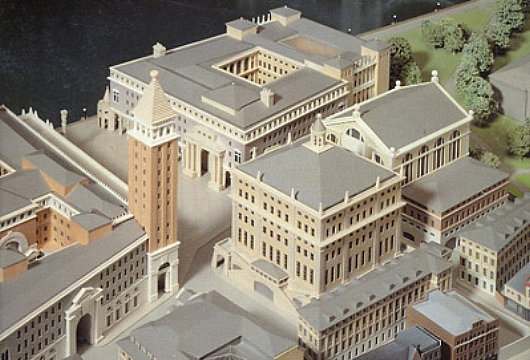

London Bridge City: The Neo-Venetian Scorned

JOHN SIMPSON AND Partners  are one of the most prominent firms promoting classical architecture and urban design in Great Britain. They are perhaps most widely known for the work they did on the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace, as well as for the rejected scheme to redevelop Paternoster Square next to St. Paul’s Cathedral. Contemporary to their ultimately unsuccessful Paternoster Square bid was another ambitious scheme, Phase Two of the London Bridge City development. For Phase Two, Simpson composed a miniature Venice-on-the-Thames complete with Piazza San Marco and ersatz campanile. There seems, however, to be something just a bit un-English about the whole project. There are numerous examples of Ruskinian Venetian buildings throughout Britain, and indeed the Commonwealth, but an entire complex of Anglo-Neo-Venetian seems a bit over-the-top. Still, one can’t deny preferring a touch of Simpson’s over-the-top Venetian to the glass-plated boredom developers usually offer the public.

are one of the most prominent firms promoting classical architecture and urban design in Great Britain. They are perhaps most widely known for the work they did on the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace, as well as for the rejected scheme to redevelop Paternoster Square next to St. Paul’s Cathedral. Contemporary to their ultimately unsuccessful Paternoster Square bid was another ambitious scheme, Phase Two of the London Bridge City development. For Phase Two, Simpson composed a miniature Venice-on-the-Thames complete with Piazza San Marco and ersatz campanile. There seems, however, to be something just a bit un-English about the whole project. There are numerous examples of Ruskinian Venetian buildings throughout Britain, and indeed the Commonwealth, but an entire complex of Anglo-Neo-Venetian seems a bit over-the-top. Still, one can’t deny preferring a touch of Simpson’s over-the-top Venetian to the glass-plated boredom developers usually offer the public.

London Bridge City, Phase Two was proposed in the aftermath of the hugely popular speech by Prince Charles in which he condemned a planned modernist addition to the National Gallery as a “monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend”. A bit of a donnybrook erupted between the architectural elite on the one hand (supporting the carbuncle) and the public on the other (supporting the Prince of Wales) and many a property developer was caught in the rhetorical crossfire. LBC’s backers decided, as an act of pragmatism, to come up with three radically different schemes in different styles and present them for consideration. (more…)

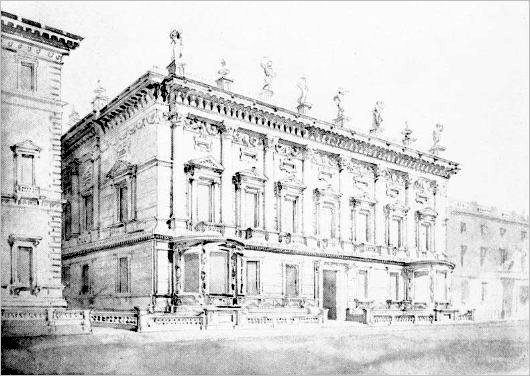

Cockerell’s Carlton Club

Charles Robert Cockerell is best known for designing both the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford and its Cambridge equivalent, the Fitzwilliam Museum. He is also, alongside William Henry Playfair, responsible for the twelve-columned National Monument that sits atop Calton Hill in Edinburgh — allegedly unfinished, though there is considerable debate over whether this is so. It’s not widely known, however, that the famous architect Cockerell completed a design for a new home for the Carlton Club on Pall Mall in London.

Originally Cockerell had declined the opportunity to submit a design, with such lofty names as Pugin, Wyatt, Barry, and Decimus Burton also declining the offer. A few years later, Cockerell nonetheless worked on this design for the Tory gentlemen’s club, which is superior to that conceived by another architect which was eventually built. Cockerell devised a “lofty Corinthian colonnade of seven bays” according to the Survey of London. “The columns have plain shafts, their capitals are linked by a background frieze of rich festoons, and the Baroque bracketed entablature is surmounted by an open balustrade with solid dies supporting urns and gesticulating statues.” (more…)

The Oriental Club

Stratford House, London

JUST STEPS AWAY  from Oxford Street, one of London’s busiest thoroughfares, rests a quiet little street called Stratford Place probably familiar only to Tanganyikans or Batswana seeking counsel from their countries’ high commissions. At the termination of the dead-end street sit the stately quarters of the Oriental Club: Stratford House. The club was founded in 1824, as British involvement and influence in both India and the Orient was waxing rapidly. General Sir John Malcolm, sometime Ambassador of His Britannic Majesty to the Court of the Peacock Throne (which is to say, Persia), coordinated the founding committee and advertised a club which would draw its members from “noblemen and gentlemen associated with the administration of our Eastern empire, or who have travelled or resided in Asia, at St. Helena, in Egypt, at the Cape of Good Hope, the Mauritius, or at Constantinople.” (more…)

from Oxford Street, one of London’s busiest thoroughfares, rests a quiet little street called Stratford Place probably familiar only to Tanganyikans or Batswana seeking counsel from their countries’ high commissions. At the termination of the dead-end street sit the stately quarters of the Oriental Club: Stratford House. The club was founded in 1824, as British involvement and influence in both India and the Orient was waxing rapidly. General Sir John Malcolm, sometime Ambassador of His Britannic Majesty to the Court of the Peacock Throne (which is to say, Persia), coordinated the founding committee and advertised a club which would draw its members from “noblemen and gentlemen associated with the administration of our Eastern empire, or who have travelled or resided in Asia, at St. Helena, in Egypt, at the Cape of Good Hope, the Mauritius, or at Constantinople.” (more…)

An Evening at the Travellers Club

Photo: © Zygmunt von Sikorski-Mazur

TO CLUBLAND, THEN, for a book launch. Of course the secret about book launches is that they are often enough a convenient excuse to assemble a whole troop of interesting characters together, with the introduction of a newly published volume occupying a secondary (while nonetheless prominent) role. In this, our esteemed hosts Stephen Klimczuk and Gerald Warner of Craigenmaddie, authors of Secret Places, Hidden Sanctuaries, exceeded themselves. For me, the evening actually began not in the Travellers but just around the corner in the Carlton Club. Rafe Heydel Mankoo had suggested meeting up there for a drink or two or three before proceeding thencefrom toward the book launch at the Travellers. Pottering over from Victoria, I arrived at the Carlton and was guided towards the members’ bar where I easily found Rafe nursing a drink beside the hearth.

The usual updates were exchanged of various goings-on that had taken place since our last combination in August. Conversation naturally turned to Canada (where Rafe was raised) and shifted to New Zealand just before we greeted the arrival of Guy Stair Sainty. Guy I first met just four years ago while enjoying a pilgrimage to Rome. We happened to stumble upon him in the Piazza San Pietro (as one does with an odd frequency in the Eternal City), and, as it was my birthday, we invited him to join us for some champagne at this little place that overlooks the square. Guy was then in the midst of completing for Burke’s Peerage the massive, two-volume World Orders of Knighthood & Merit, or “WOKM”, which loomed restively on a nearby table as we sipped our drinks in the Morning Room. (more…)

The Wolseley

Our itineraries only had us both in London for less than twenty-four hours. Sam, now lawyering in his native Lancashire — “Recusant country, Cusack, you’d love it.” — was down in London for a party on Friday night. “How about a coffee Saturday morning before I head back up north?” Why not. “It’d have to be early though.” Blast. How early? “Say… 10 o’clock?” Well, that’s not so bad is it! Where to meet? “The Wolseley, next to the Ritz.” Never heard of it, but Sam must know what he’s up to.

Here, I have to admit that I usually hate public places devoted to the consumption of food. Restaurants irritate me and I infinitely prefer the dinner party to the restaurant appointment. Even the places I like, I actually despise in one way or another. But the Wolseley failed to irritate me in the slightest, which earns it very high marks indeed in the Grand Book of Cusack. The staff are friendly but suitably removed, the coffee is excellent, and the food tasty with portions just the right size. On Sam’s recommendation I tried the Wiener Kaffee, and ordered French toast for myself, Sam taking pancakes. Everything was just as it should be, and without any fuss. What better praise could one give such an establishment? (more…)

Dinner at Chiara’s

“Chiara,” I asked, “How will you ever know whether your friends are truly your friends or if they really just love your pumpkin risotto?” “You know,” she replied in her thick Italian accent, “this is a serious problem!” The possibility of never cooking pumpkin risotto again was mooted, but wholeheartedly condemned by all in attendance. The very thought was an affront to our salivating taste buds. (more…)

A Wander Through the V&A

When on earth was the last time I was in the V&A? To be honest, I’ve no idea, though I’m certain my first visit was (like that of many others) as a wee one, the summer after kindergarten to be precise. It’s a stonking great place with tons of stuff in it, and one of the startling few that deal with architecture as a subject in its own right. (A fact which wins admiration in the heart of this architecture fan).

When on earth was the last time I was in the V&A? To be honest, I’ve no idea, though I’m certain my first visit was (like that of many others) as a wee one, the summer after kindergarten to be precise. It’s a stonking great place with tons of stuff in it, and one of the startling few that deal with architecture as a subject in its own right. (A fact which wins admiration in the heart of this architecture fan).

Of course the Victoria & Albert Museum has been fresh in the minds of many most recently for the re-opening of its Medieval & Renaissance sculpture galleries. The new arrangement cost over £30 million, took seven years to complete, and includes ten new display rooms displaying, as the Guardian put it, “a world of ravishing luxury”. So it seemed silly not to have a little wander round the South Ken institution yesterday, especially since it was a rainy afternoon. (more…)

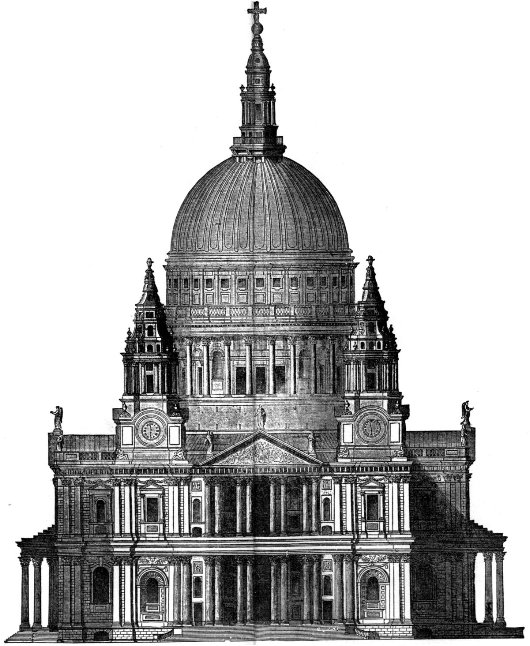

The Oratory as It Was Built

Since we explored Brompton Oratory as it might have been, here is the Oratory as it was built. The façade were finally completed in 1893 to a design by George Sherrin, with the dome following in 1894-95 by Sherrin’s assistant E. A. Rickards. How is the Oratory as depicted above different from the Oratory today? The fence and gates were replaced with a curved design at some date unknown to me, perhaps in response to a road-widening scheme.

No. 82, Eaton Square

In it’s long history, the address of No. 82 Eaton Square in London has housed a Major-General of the East Indian Cavalry, a Lord Strafford, a Lord Bagot, an Earl of Dalhousie, an Earl of Clare, a Duke of Bedford, and Queen Wilhemina of the Netherlands — thankfully not all at once. It’s probably best know for its half-century as the Irish Club, a much-favoured drinking & smoking spot for the community of Gaels in London. The club was founded in 1947, with a number of pre-existing Irish clubs merging into it. George VI — grateful for the devoted service of the Irish who volunteered for his armed forces during the Second World War — heard that the club was in search of premises and asked the Duke of Westminster, one of the largest landowners in London, if he could help. The Duke provided the leasehold of No. 82 Eaton Square to the Irish Club for a nominal sum. (As it happens, the 4th Duke’s son served as a Unionist MP for Fermanagh & South Tyrone, and later in the Northern Irish Senate). (more…)

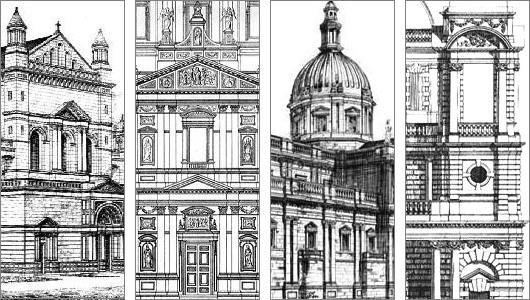

Brompton Oratory as It Might Have Been

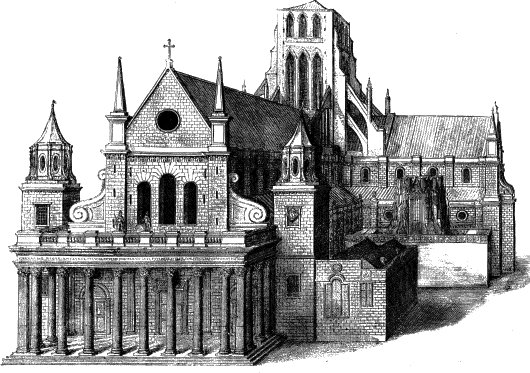

Failed Entries of the 1878 London Oratory Architectural Competition

ARCHITECTURAL COMPETITIONS have always fascinated me because they give us the opportunity to glance at multiple executions for a single concept, to see different minds solve a “problem” with their own particular formulas and theorems. The designs of many of the world’s prominent buildings were chosen by competition, perhaps the Palace of Westminster — Britain’s Houses of Parliament — is most famous among them. When the Hungarian Parliament held a competition to design a grand palace to house the body, it found the top three prize designs so compelling that it built the first-prize design as parliament and the second and third places as government ministries nearby. To my surprise, I have only ever come across one book which adequately surveyed the subject of competitive architecture, Hilde de Haan’s Architects in Competition: International Architectural Competitions of the Last 200 Years. Most of the contests covered in the book are, naturally, for government buildings of national importance — private clients usually have a very firm idea of what they want and choose an architect accordingly.

One building not mentioned in the book but nonetheless very dear to me (and no doubt to many readers of this little corner of the web) is the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary of the Congregation of the London Oratory, more popularly known to friend and foe alike as the Brompton Oratory. It was the first church in Britain in which I ever heard mass, the summer after kindergarten when I was still but a tiny, blond-haired whippersnapper, in the midst of my first visit ever to the Old World, and the Oratory made quite a strong impression upon my young mind. It is usually one of my very first ports of call whenever I am in the capital, and I once even managed to slip in having just arrived at Heathrow while making my way to King’s Cross and the train to Scotland.

The Brompton Oratory is known for having good priests, traditional liturgy, and beautiful architecture. The final design was by one Herbert Gribble, but there was quite a bit of to-ing and fro-ing before Gribble was selected. The temporary church which had been erected on the site had been condemned by one critic as “almost contemptible” in its exterior design. In 1874, the Congregation of the Oratory (which is to say, the priests) put out an appeal for funds towards the construction of a permanent church. The 15th Duke of Norfolk obliged with £20,000 to get the ball rolling, and the next year a design by F. W. Moody and James Fergusson was agreed upon in principle. But the Reverend Fathers soon began to get creative and hatch ideas and contact other architects and very soon it was claimed that there were as many counter-proposals as there were priests of the Oratory, and perhaps more. A pack of clerics supported a suggested design by Herbert Gribble, but no accord could be reached among the Congregation as a whole.

In January 1878, then, it was announced that a competition would take place to decide the design of the permanent church of the London Oratorians. First prize was £200, with £75 for the runner-up. All entries had to meet the certain requirements drawn up by the Congregation. The style was to be “that of the Italian Renaissance”. The sanctuary, at least sixty feet deep, must be “the most important part of the Church. … Especially the altar and tabernacle should stand out as visibly the great object of the whole Church.” The minimum width of the nave was fifty feet, and maximum length 175 feet. Subsidiary chapels must be “distinct chambers”, not merely side altars. One aspect not mentioned was the projected execution costs of the designs — “an omission criticized by architectural journalists and disgruntled competitors,” the London Survey tells us, “whose designs called for expenditure ranging from £35,000 to £200,000”.

Over thirty entries were submitted to the competition, and Alfred Waterhouse was commissioned by the Fathers to provide comment on the submissions. Significantly, George Gilbert Scott, Jr. submitted a design, though I haven’t been able to get my hands on any depictions of it. Waterhouse praised it as “of no ordinary merit. … I feel that it is impossible to speak too highly of its beauty, its quiet dignity, its absence of all vulgarity and its concentration of effect around the high altar.” (more…)

Diary

I have been spending the past few days in a flat at the corner of Holland Park Avenue and Portland Road, in this verdant corner of the capital. The flat is clean, capacious, and handsome, but terribly modern. Indeed, it is so modern that it will soon be old; it will not exhibit the old age of the time-honoured and true, but rather the tawdry oldness of what had only recently been new. Pedantic students of interior design will study photos of it and discern “2008 I’d say… no! 2009!” But for now, it is still new, still fresh, and so, like a tomato fresh for the plucking, we will enjoy it while its moment is precisely appropriate.

Until now, I hadn’t much knowledge of this part of London, but find it a happy place to be in August. The weather has been mild and kind, and I spent part of the afternoon reading de Maistre — the St. Petersburg Dialogues — in the formal garden in Holland Park. The avenue itself is tree-lined, or rather tree-engulfed, such is the plentiful shade, and has a small selection of cafés: the Paul boulangerie which is becoming omnipresent, and the Valerie patisserie, both chains. Cyrano, at No. 108 Holland Park Avenue, is much preferred, and I decamped there for a light breakfast with a copy of the Scotsman from the local newsstand (the one on Ladbroke Grove, rather than the smaller one by the tube stop) while avoiding the miserable Irish cleaning lady who returns the modern flat to its pristine whiteness every Thursday morning.

Then to the Royal Academy, for the Waterhouse show. What an interesting artist! His earlier works so precise in detail and, for lack of a better word, academic. Yet in his later pieces, you can find a certain willingness to obfuscate, perhaps an admission that reality is not quite so precise and that the most accurate portrayal of reality requires a few lines to be blurred. Faces, and indeed all forms, remain clear throughout, but the architectural coldness of the earlier works on display gradually evolves to a more fluid depiction of Greek mythos and Keatsian tales. Waterhouse can vary in his details from the almost photographic to verging on impressionism in a single painting. Was that his intention? It was certainly the result.

My viewing companion — an old university friend — and I agreed that throughout all the themes portrayed by the artist one can’t help but feel an overwhelming Victorian-ness. Is this ex post facto because we know Waterhouse to be an High Victorian artist, or is there actually some inherent quality in the works that calls to mind that era? Very difficult to say, but those in London should not miss this exhibition of a popular yet under-appreciated artist — the Jack Vettriano of his day.

Who is in London in August anyhow? The text messages sent out, and their replies promptly received. “I’m in Geneva! Will be in Luxembourg next week if you’re on the continent.” I am not and will not be on the continent. “I have been unexpectedly called to Africa.” Well I’ve just come from there, though not the Sudan thank God. “You’re welcome to come to Gozo between the 5th and 15th for a pleasant, quiet holiday.” I will have returned to New York by then, alas. “Am up north in Lancashire; you’re welcome to come and visit, sample our recusant history!” Just haven’t got the time, alas.

But while many have escaped for the month, many yet remain. An afternoon drink at Rafe’s, with Fr. Rupert and Alex Williams. The Carlton is being refitted, so it was drinks at the East India Club instead with another university friend, during which we concur that office jobs are the absolute pits and we should have studied agriculture with the country girls at Cirencester rather than getting tawdry MAs in Scotland. There is no greater affirmation of the consequences of original sin than the omnipresence of the 9-to-5 office job.

Astute observers of this little corner of the web (if indeed we can use the plural for such a subset of the earth’s population) will recall an incident over two years ago now in which a certain Jack Russell terrier became rather more involved with my lower leg than I had envisioned was ideal. The dog, which goes by the name of Cicio Stinkiman, had noticed me playing with the only seeing-eye-dog in Scotland that knows how to genuflect and resented the attention I was paying to the bitch, to whom he obviously professed some attachment, ran up, and bit me in the calf.

You can imagine my surprise when I learnt that the beast in question is actually now not only living in London but actually residing in the Oratory. Indeed I saw the beast from a distance while waiting on Brompton Road for the Friday evening mass last week. His owner graduated from university (in Scotland, like all the wisest people) two years ago now but his mother banned poor Cicio Stinkiman from the German palace he might otherwise call home, perhaps informed along the voluptuous grapevines of Europe of the horrendous incident in which the beast had taken an unwelcome interest in my lower leg.

I am being far too unfair to poor Cicio, for he did apologise, and looked up at me with terribly apologetic eyes. Admittedly, that might’ve been because his master stood nearby holding a rolled-up copy of the Catholic Herald most threateningly. Still, pity the poor ignorant beasts. They have no conscience, and thus no real malice. Only we humans, with the freedom we abuse so easily, can claim that dubious achievement.

Buckham’s Britain

The Daily Telegraph shows us a number of photos taken by Alfred Buckham, an aerial photographer of the 1920s. Buckham was introduced to the art during his time with the aerial reconnaissance branch of the Royal Naval Air Service in the First World War.

The Daily Telegraph shows us a number of photos taken by Alfred Buckham, an aerial photographer of the 1920s. Buckham was introduced to the art during his time with the aerial reconnaissance branch of the Royal Naval Air Service in the First World War.

The images themselves are composite photographs combining actual aerial views of cities and landmarks throughout Great Britain with views of the aircraft of the day flying through the skies.

As the Telegraph notes, Buckham “eschewed safety devices, saying: ‘I have used a safety belt only once, and then it was thrust upon me. I always stand up to make an exposure and, taking the precaution to tie my right leg to the seat, I am free to move about rapidly'”.

A new book on Buckham, A Vision of Flight: The Aerial Photography of Alfred G. Buckham, has just been written by Celia Ferguson, and is published by The History Press.

New Yorker Elected Mayor of London

Congratulations to that most-honoured son of the Empire State, Mr. Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson MP, more commonly known as Boris, on his election to the mayoralty of Greater London. Mr. Johnson was born on these sacred shores some forty-four years ago on a pleasant June day. Boris has politics in the blood as his father Stanley is a former Conservative MEP, but let us hope he does not take after his great-grandfather, Ali Kemal Bey, who made enough unfortunate decisions during his brief tenure as interior minister of the Ottoman Empire that he was knicked from the barber shop of the rather-smart Tokatlian Hotel in Constantinople and lynched shortly thereafter.

Strangely enough, this is not exactly the closest connection New York and London have ever had. Sir Gilbert Heathcote, 1st Baronet was Lord Mayor of London in 1710 while his brother Caleb Heathcote was Mayor of the City of New York, exhibiting how interconnected our transatlantic British world was in those days. Caleb Heathcote was also Lord of the Manor of Scarsdale, which is just five minutes north of here on the train. Created in 1703, Scarsdale was the last manor granted in the entire British Empire. There were about a dozen manorial lordships here in New York, bringing the proud heritage of feudalism to the New World. The Manor of Gardiner’s Island survives to this day as the only manor in America in which the land is still entirely owned by the descendants.

The bulk of manorial privileges (incorporating the pre-existing patroonships from the olden Dutch days) were, alas, abolished in the 1840s, with the final holdouts taken care of in some legislation of 1911, but the Lord of the Manor of Pelham was presented with a fatted calf each St. John’s Day from the City Council of New Rochelle (honoring the Huguenots’ agreement purchasing the land from the Pells) well into the twentieth century.

The Heathcote name survives, in Derbyshire I believe, but not in America. Caleb Heathcote married the daughter of Col. William Smith, Chief Justice of the Province of New York, but had only daughters.

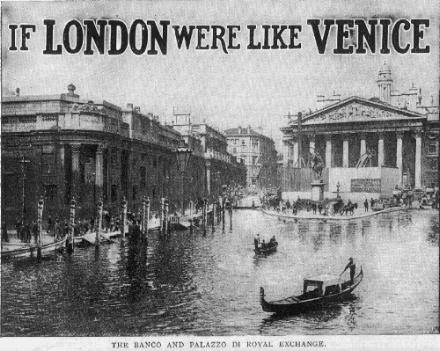

If London Were Like Venice

No doubt you remember If London Were Like New York, now we bring you If London Were Like Venice. A rather charming improvement, in my opinion. (more…)

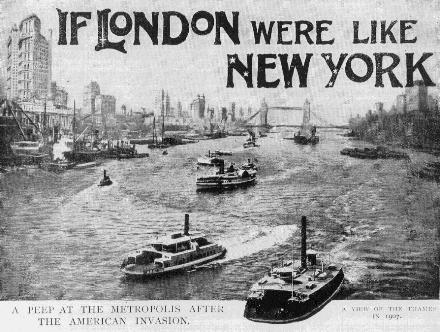

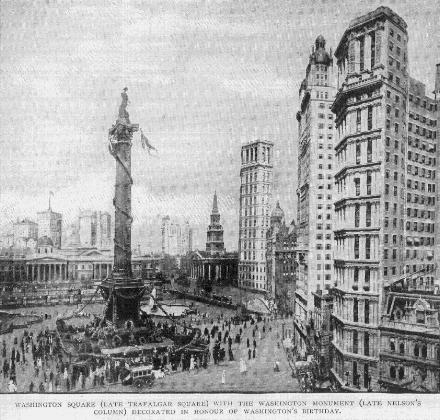

If London Were Like New York

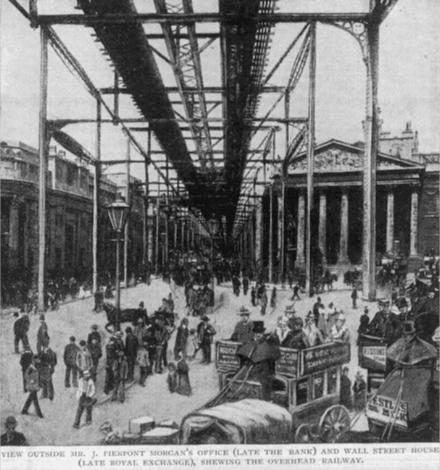

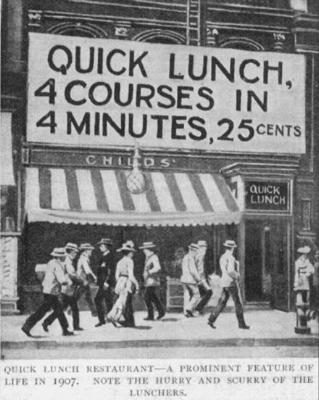

I stumbled upon this rather drole piece from 1902 about the prophesized New-Yorkification of London in Harmsworth’s Magazine. “If London Were Like New York: A Peak At The Metropolis After The American Invasion” is accompanied by some amusing illustrations of the anonymous authors vision of the future.

Trafalgar Square is rededicated to George Washington, and decorated to celebrate his birthday.

An el is built right through the heart of the City.

There’s even a precursor of our famous American fast food. Perhaps the most prophetic of the author’s predictions!

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories