London

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Canalside Wanderings

The sun put its hat on this weekend, and after a delicious and vaguely German breakfast by King’s Cross on Saturday I fancied a little canalside wandering. Walking the Regent’s Canal from the new Central Saint Martins all the way to Paddington, I stumbled across the Catholic Apostolic Church in Little Venice (above). It has been over ten years since I popped in to the former Edinburgh outpost of this strange and fascinating denomination, now much reduced in numbers since its apex in the late Victorian period. (more…)

Diary

EVERYONE was at the Opera last night. It was the final performance of a magnificent production of Il trittico, Puccini’s triptych of three one-act operas alluding to the Divine Comedy. While I go to the theatre fairly often I hadn’t been to the opera since many many moons ago when I was dating una Italiana who had a taste for it. These days, the Mad Architect is one of the handful of people I tend to go see things with. His tastes are similar to mine but he is easily irritated and always seems to pick a fight with some other member of the general public (or once, on the Eurostar, the barman – but it was actually deserved in that case). This can provide some intense amusement to the observer so long as you are prepared to disown him totally at a moment’s notice (which I have yet to do).

Anyhow, during the first interval we wandered out onto the open terrace – from whence smoking has since been banned – and who should we stumble upon but the charming and deeply fun Valentine Walsh, one of the finest art restorers in Europe, with a relation of hers. Then, but a few seconds later, our own roving reporter Alexander Shaw appeared with an old school friend. As I sometimes point out, London can feel like a delightfully small town. The Spectator’s Rod Liddle and Michael Portillo of ‘Great Railways Journeys’ fame were also in evidence, but we let them be.

But what of the opera? The first act, Il tabarro, is set on the banks of the Seine and was well sung but more than the singing I admired the highly architectural setting imagined by the mononomical set designer ‘Ultz’. (How one both derides and admires the arrogance of arrogating to oneself a single name – but then, like Hitler and Stalin, I myself am often known by surname alone.)

The second one-act opera in this triptych, Suor Angelica, was the real meat. Here is a deeply intense display of love and hatred, sin and repentance, compounding personal tragedy with the reality of mortal sin. Sadly we were deprived of the vision of the Blessed Virgin called for in Puccini’s original but it was surprising that director Richard Jones played the opera’s Catholicism straight and frank, without any of the usual modern snobbish sneering. Ermonela Jaho was powerful in the title role, convincing. Valentine was in tears.

But if Il trittico is like a three course meal then Gianni Schicchi is the delicious pudding. When Buoso Donati dies and leaves all his wealth to a monastery, his eight predatory relatives are forced to call upon the clever peasant Gianni Schicchi to use his worldly cunning to fake a new will. This is Italian farce at its most amusing but also its most beautiful and as Gianni includes the most well-known operatic song in the world – O mio babbino caro – it’s a crowd pleaser as well.

The Mad Architect noted that the English don’t really enjoy opera: they take it far too seriously, whereas the Neapolitans love it and join in the singing, even if they don’t know the words. Alexander thinks the Royal Opera House has become little more than a giant cruise ship for plutocrats and then descended into telling us his plan to sell Deptford to the French (or was it to Hong Kong?).

My only complaint was the surtitles, which often did not match the original Italian. This happens on Scandinavian crime dramas as well, in which non-blasphemous swear words are inaccurately translated as blasphemous English ones. But this is probably some contrived vogue in the realm of translators, that you mustn’t translate things as they are but to something somewhat similar but not quite the same, thus depriving you of the character of the original language.

What’s next on the agenda then? Sometime at the Old Vic, I think, and then something at the Almeida, and later on this year there’s Ryszard Kapuściński’s book on Haile Selassie, The Emperor – “I was working in the Ministry of Ceremonies then, Department of Processions…” – being done in a stage version at the Young Vic.

Ball

The Cusackian table used to be the only one having our pre-ball drinks at the Cavalry & Guards Club (thanks to Maj Ibbs & Capt de Stacpoole) but this year the place was choc-a-bloc with ballgoers. Our ladies were looking particularly lovely, though there were moments when various of their fur accoutrements were redeployed as judges’ wigs and sentence was passed on those worth of condemnation.

Despite the rather late hour I left the after-party, I somehow made it to the 11 o’clock mass at the Oratory the following morning and noticed a somewhat depleted congregation (though added to by the presence of Gerald Warner up from Scotland). Very wisely the ball organisers arrange a special afternoon mass at 2 o’clock for survivors, but by the time it commenced I had not only already fulfilled my Sunday obligation but also downed a delicious plate of pappardelle and was en route back home to bed and further recovery.

Diary

It is truly a sad thing for a summer to end, and yet it is an inevitable part of the endless cycle of life. July was full of its annual rites: two weeks in Lebanon and then the traditional festivities associated with the return of the OMV contingent from Lourdes — jugs of Pimm’s at the Scarsdale followed by the manic dinner, drinks, dancing, and smoking at Pag’s late into the night. Miss S. had always avoided the Pag’s part of the festivities, decrying it as a futile attempt to prolong the jollity. She decided to come along this year, however, and enjoyed it so much she stayed well past two in the morning. In fact, I think she was still there when I left.

So it didn’t really seem like summer really kicked off until August. (more…)

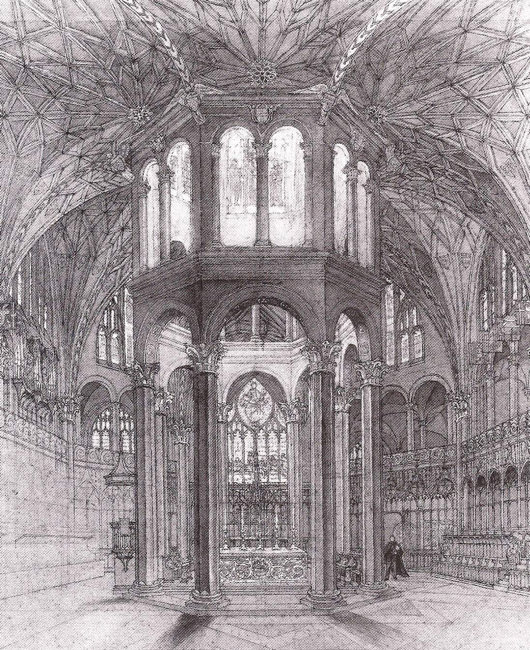

St Paul’s Gothicised

Victorian England went mad for the medieval, often neglecting or destroying buildings and structures of classical design along the way. Wren’s classical rood screen for Westminster Abbey is probably no great loss, but just imagine if his masterpiece, St Paul’s Cathedral, had been gothicised.

Just such was imagined by the architectural sketch artist C.A. Nicholson in two drawings he sent to the Architectural Record (albeit in the 1910s, not the Victorian era). Nicholson was inspired by an image printed in a previous issue of the Record showing the front of Peterborough Cathedral transformed into a classic design.

Of course before the Great Fire, Old St Paul’s was a Gothic cathedral.

Curiosity Killed the Cat

Or: our love/hate relationship with the Phoenix, Chelsea

It was an unusually warm evening for a night in March, which is to say that it was not horrendously cold and you could tarry a while outside without fear of frostbite. Given the nature of his job, Nicholas is not frequently free to socialise, as he has to be doing certain things in certain places at certain times, which sometimes involves being in Greece or a sudden trip to Anguilla (“I’m not doing any more Caribbean islands — I’m fucking tired of them.”). But when he does manage to free himself from indentured servitude, we often find ourselves at the Phoenix on Smith Street.

All sensible right-minded people love the Phoenix and hate the Phoenix. It is a wonderful place, comfortable and delightful, yet somehow attracts the very worst and most tiresome lot of humanity. “Look at these estate agents,” Nicholas moans in the put-on snobbery which has become one of his traits. “They all live in Fulham I’m sure.” (Which is rich, as I live even beyond Fulham). Kit and H. were dining there with Ivo & la B a week or two earlier (or later) and such was the tiresomeness of the crowd that Kit texted Ivo “What a bunch of overgrown yuppies” (or something along those lines).

It’s delightful during the day, and there was one afternoon not long ago when, sauntering down the King’s Road, I ran into Prof. Pink on his way to John Lewis and managed to waylay him into an enjoyable conversation at the Phoenix over two large glasses of the house white. But during the evening the crowd gets so horrendously up-itself that it almost becomes an attraction in itself. “It’s ten o’clock on a Friday night. Shall we drop in to Smith Street and see how awful everyone is?” The experience ends up infecting one with a reverse snobbery almost as snobbish and pretentious as the pretentious snobbery one is reacting against in the first place.

As I was saying, it was a warm evening and Nicholas managed to find an ideal parking spot within sight just round the corner on Woodfall Street. I think it was a Friday or a Saturday so naturally the place was packed inside and I’m partial to the occasional Dunhill so enjoying an exceptionally refreshing cider outdoors with a cigarette was the obvious way forward. I lit up and Nikolai — very generously, as I’m sure it was my round — went inside to brave the crowds in search of drink. Now the curious thing about the smoking ban is that it has turned previously insular cells of humanity — smokers, that is — into a sort-of fraternité universelle. People who have absolutely nothing in common but for being at the same drinking establishment now, for better or worse, through the medium of tobacco, enjoy a recognisable commonality which can frequently turn conversational.

A little Spanish man with a moustache had a party inside celebrating his birthday — 31st, I think — and he ventured outdoors for a smoke and somehow or other conversation was initiated. A pleasant enough fellow but his chat was unexceptional and was suddenly interrupted by the arrival by cab of two tall-ish and rather fashionable Azeri girls, who may have been friends of friends of his or may have had nothing to do with him at all. Being a chatty Spaniard (and perhaps a bit ambitious) he engaged them in conversation almost as soon as they alighted their cab.

After the innocuous pleasantries of introduction all round he eventually asked the Azeri duette, “So where do you girls live?” “Knightsbridge” they replied. “Ah, cool, I’m in Knightsbridge a lot,” our Spanish friend replied as Nicholas, turning away, launched upon a severe, disapproving rolling of the eyes. “Why?” I interjected, somewhat mischievously pricking the balloon of his pretentiousness. After all: what possible excuse could anyone who neither works nor lives there reasonably have for being in Knightsbridge a lot? He turned towards me and with an irritated smile said “My friend, you are too curious; you ask too many questions.”

The Azeri girls remained unconvinced of him, and the birthday boy, having finished his cigarette (which I think came from my pack), sheepishly returned inside where his presumed friends had doubtless continued the celebration of his birth in his brief absence.

But we still all love the Phoenix.

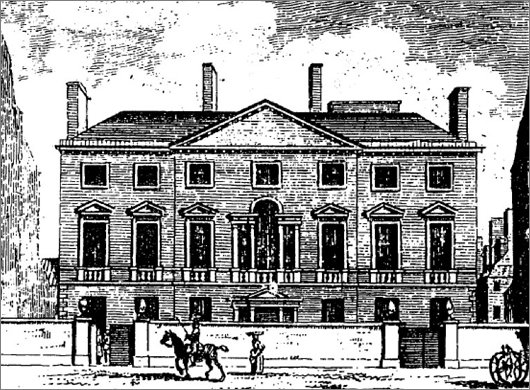

No. 6, Burlington Gardens

Sir James Pennethorne’s University of London

German university buildings are an (admittedly unusual) obsession of mine, and I’ve often thought that No. 6 Burlington Gardens is London’s closest answer to your typical nineteenth-century Teutonic academy’s Hauptgebäude. And the connection is appropriate enough, as No. 6 was built in 1867-1870 for the University of London in what had once been the back garden of Burlington House (which at the same time became home to the Royal Academy of Arts). Despite the building’s Germanic form, the architect Sir James Pennethorne decorated the structure in Italianate detail, providing the University with a lecture theatre, examination halls, and a head office. Pennethorne died just a year after drafting this design, and his fellow architects described it as his “most complete and most successful design”.

The University of London was founded as a federal entity in 1836 to grant degrees to the students of the secularist, free-thinking University College and its rival, the Anglican royalist King’s College. It now is composed of eighteen colleges, ten institutes, and a number of other ‘central bodies’, with over 135,000 students.

Since its founding, the University had been dependent upon the government’s purse for funding, as well as for housing. Accomodation was provided in Somerset House, then Marlborough House, before evacuating to temporary quarters in Burlington House and elsewhere. It was not until the 1860s that Parliament approved the appropriate grant for a purpose-built home for the University to be erected in the rear garden of Burlington House. (more…)

The Lady Altar

The Oratory Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary,

Brompton Road, London

In the south transept of the Brompton Oratory is the altar dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, perhaps the finest altar in the entire church. It is a favourite place for getting in a few prayers and offering a candle or two or three or four. At the end of Solemn Vespers & Benediction on Sunday afternoon (above) it is where the Prayer for England is said and the Marian antiphon sung.

The Lady Altar was designed and built in 1693 by Francesco Corbarelli of Florence and his sons Domenico and Antonio and for nearly two centuries stood in the Chapel of the Rosary in the Church of St Dominic in Brescia. That church was demolished in 1883, and the London Congregation of the Oratory purchased the altar two years beforehand for £1,550.

The statue of Our Lady of Victories holding the Holy Child had previously stood in the old Oratory church in King William Street, and the central space of the reredos was slightly modified to house it. The Old and New Worlds are represented in the flanking statues, which are of St Pius V and St Rose of Lima — both by the Venetian late-baroque sculptor Orazio Marinali. The statues of St Dominic and St Catherine of Siena which now rest in niches facing the altar were previously united to it, and are by the Tyrolean Thomas Ruer.

London Lately

From a Pimlico rooftop, Friday afternoon.

At lunch, Friday.

A Saturday Mass in St Wilfrid’s Chapel, the Oratory.

A surprisingly sunny afternoon, yesterday in Ennismore Gardens.

A Bill Committee in the Commons

A Bill Committee meeting in one of the richly decorated committee rooms of the Palace of Westminster. The Minister is standing, rattling on in an explanatory defence of his government’s bill. Ostensibly these committees exist so that MPs can examine legislation in line-by-line detail and raise questions about whatever points or aspects they believe might cause problems if enacted.

“The question is that Clause 15 stands as part of the Bill.”

The Chairman, an MP of considerable experience, presides, assisted by a retinue of civil servants. He chews a pen and stokes his brow, frustrated by the boredom of the subject at hand. He is perhaps thinking of the weekend and the extreme unlikeliness that he will get down to the coast, and his sailboat, given the inclement weather.

A Scottish Member rises on a Point and the Minister yields the floor. Concerns are expressed about the precise meaning of Subclause 36 Paragraph C and insinuations made about potential costs. The Minister rises and suggests the Member’s criticism is excessively harsh. He then concedes he may have been imprecise in his explanation of the process involved in Subclause 36 Paragraph C.

The Doorkeeper, absurdly and arcanely attired in white tie, tails, and with the royal arms hanging from a gold chain round his neck, wears thick-rimmed glasses and leans back on a desk in a carefree fashion, blissfully paying little attention to the point the Hon. Gentleman has made in response to the proposed amendment.

“Just for the sake of clarity, we are not now talking about Amendment 13?”

“I have no intention of moving Amendment 13.”

“On a Point of Order then, Mr Chair, is it proper that the Member discuss Amendments 21 and 26 when he is not moving Amendment 13, which is the first Amendment to be considered?”

The Chairman corrects that it is perfectly alright for the Member to discuss whichever amendment he would like.

There are at least eleven civil servants in the room. One on the side hands a paper to another. He reads it and nods approvingly before passing it on to the civil servant next to the Chair. Another Member rises to discuss Amendment 54 Clause C.

“There’s an important role for an independent body to exercise scrutiny over this area and it would be wise for it to have a statutory basis.”

The entire proceedings are overshadowed by the continual sound of shuffling papers. One Member doodles on the day’s order-paper. A journalist leaves. The Member stops doodling and consults his iPhone. Then the Minister is grateful for that point. He is surprised but aware, since he was given this junior ministerial role, by the frequency with which this matter has arisen and has spoken before the relevant Select Committee.

Another Member’s face is illuminated by the glow of the iPad he is leaning over.

“Now before I become too Churchillian,” the Minister continues, “I think we’d better turn to the matter of the Amendments. Now the Honourable Member has, perhaps understandably, raised the point…”

A female Member smiles and shares a jest with one of her party colleagues. The Doorkeeper’s shift ends and he is replaced by one of his bearded confrères. The civil servant beside the Chairman folds a paper and stares unthinkingly into the distance.

“In respect for the Hon. Gentleman’s desire for continuing debate and discussion with the relevant authorities…”

“He hasn’t addressed my point about Subsection 2!”

The portly Doorkeeper moves with surprising adroitness in delivering a note from a Member to a civil servant across the room. The Minister’s PPS hands him a relevant paper. The Chairman smiles in response to one of the Minister’s light-hearted remarks.

“I’m sure the Minister will agree that this is not the beginning of the end but merely the end of the beginning.”

“If only!” a Member interjects.

It is 3:32pm. The MPs will be here for hours yet.

Don Bosco in London

Just went to venerate the relics of Don Bosco, which are doing a UK-wide tour organised by the Salesian order. There was quite a crowd waiting for the Saint’s earthly remains to be unveiled at 2 o’clock — suprising for early afternoon on a workday. Before the relics were even made viewable there were pilgrims huddled around the veiled reliquary, whom the organisers eventually had to shoo away in order to organise some proper veneration.

The faithful are able to venerate the relics at Westminster Cathedral from 2:00pm to 8:30pm today and tomorrow only, after which they will spend the next two days at St. George’s Cathedral in Southwark before returning to Italy.

Fit for a Duke in Covent Garden

Russell House, No. 43, King Street

This apartment occupies the piano nobile of a 1716 house designed by Thomas Archer for the Earl of Orford, then First Lord of the Admiralty. He obtained the lease for the site from his uncle, the Duke of Bedford, on condition he tear down the house located there and build a new one. Batty Langley, the eighteenth-century garden designer and prolific commentator hated it, and devoted over 200 words of his Grub Street Journal (26 September 1734) to slagging it off. The Grade II*-listed building looks onto Covent Garden Piazza and has seen a number of uses over the years. (more…)

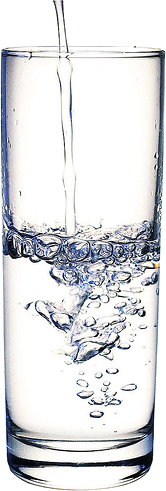

London’s Fallen Water

A cursory investigation into the metropolis’s drinking water yields results that veer towards the somewhat disturbing

by ALEXANDER SHAW in London

UNDERSTANDING  enables self-preservation, but occasionally leads us out of Eden too. Thus, I’m not encouraging you to understand how London’s water is recycled, I’m merely tempting you to.

enables self-preservation, but occasionally leads us out of Eden too. Thus, I’m not encouraging you to understand how London’s water is recycled, I’m merely tempting you to.

Education is like lighting a fire, not filling a bucket. One realisation leads to another:

Q: What happens when the ice cubes melt in a brimming Tumbler of Scotch?

A: Nothing – so the disappearance of the polar icecap won’t raise sea levels. So I can drive an eight-litre Bentley after all.

Q: What happens when two cars each travelling at 30mph collide head on head?

A: The Bentley’s CD player skips a track and someone spends the afternoon picking a Nissan Micra out of the radiator.

Point by point, basic wisdom allows us to unpick the paranoid egalitarian ideas subversively presented by the Marxist GCSE Physics curriculum.

However, I am horrified that, even with my impeccable logic, it has taken me three years to realise that London’s recycled potable water supply harbours a rather dirty secret. It was the lime scale in the kettle which gave it away. We all know that, as with many cities, London recycles its water. But why, after the process of evaporation and recondensation, does limescale remain in the supply? The answer, to my unutterable horror, is that it is not recycled by evaporation.

I’ve given up trying to get straight answers from Thames Water about exactly what goes on. Like the pro-choice lobby and socialist economists, they gloss over all manner of sins with a vast lexicon of euphemisms.

For ‘carbonaceous waste,’ read: diarrhoearic faeces comprised of doner kebabs and salted French fries, crammed past cankerous lips by nail-bitten greasy fingers of obese female students in bus stops at 3am. For ‘nitrogenous waste,’ read: cheap lager, churned through proletarian digestive systems whose uncircumcised owners moan with relief as the steel urinal tangs of ammonia – gobs of chewing gum and Mayfair fag butts collecting at the foot of the drain. After a brief sifting and filtering, these ‘wastes’ then gush out of London showerheads. The final confluence of the city’s vomit is on my own pale, patrician flesh.

It might not disturb me so much if the water were sent back to the same house, or even the same postcode. At least in Chelsea, we would be drinking the urbane fruits of some anorexic supermodel’s colonic. But no, the city’s water is pooled in something called the ‘Thames Water Ring Main,’ which sounds ghastly, and is so huge that it reaches down to somewhere called ‘zone four.’

I have read an account of the process used to purify our sewage on Thames Water’s website. First they filter it ‘through a rake’ (right, OK), and then ‘most of the solids are removed by settlement.’ After that, they skim off the cleaner bit of what, by then, is basically an un-shaken-up shit smoothie and pump it through a gravel pit of bacteria. Then they send it back to my house.

The internet consensus seems to be that, on average, our tap water has gone round this system approximately seven times and, for those who still have diehard faith in the system, people start to feel nauseous when they drink 11th generation water. So yes, it does get muckier each time.

“Well, if we don’t get ill it must be alright,” a friend of mine concluded, taking a defiant swig of the tap water she’d just ordered in a café. It seems this may also be the underlying philosophy of Thames Water. I find it an unsettlingly laissez faire approach.

The U.S Geological Survey discovered that the dozens of trace chemicals – often derived from medication – which slip through modern filtration processes amount to ‘only a thimble full in an Olympic pool.’

Only!?! If that thimble were of blood, a shark would smell it. If it were Polonium 210, it would be enough to wipe out the entire city. And, heavens above, any folk who take homeopathy seriously will consider that sort of dilution the medical equivalent to downing a pint of dysentery or bathing in the cesspit of a Kinshasa prison.

Furthermore, the ‘fresh’ water that is brought in to our supply from the Thames contains the only-slightly-treated sewage of the settlements upstream. I’m going to guess that 95% of the female populations of Reading, Cowley, Slough and Swindon perform some type of medical injunction upon their reproductive system every Saturday (or Sunday morning, God forbid). And, of course, what goes in must come out.

A Drinking Water Inspectorate report submitted to Defra in 2007 proclaims that our UK filtration techniques ‘can result in removal rates of more than 90% for a wide variety of pharmaceuticals.’ Oh, good! Only less than 10% gets back in! Further down the report, we read: ‘Very limited data were available for the concentrations of pharmaceuticals or illegal drugs in UK drinking waters, but data from the rest of Europe and the USA have shown that concentrations in finished drinking water at treatment works are generally =100 ng.l-1’ (which sounds like another euphemism to me). The report continues to say that the filtration processes are ‘not specifically designed to remove pharmaceuticals and several compounds have been reported in finished drinking water.’

The report is available in summary here. I was retching and gagging by the third paragraph.

It comes as little surprise to me that our perverse society seems more preoccupied with the treatment of the ‘sludge’ which is siphoned out, than the ‘water’ which is pumped back in to our taps. The Thames Water reports abound with the ‘European Sludge Directive,’ the worthy ‘good chemical status,’ and not forgetting, of course, the all-important ‘Safe Sludge Matrix.’ I have already expounded upon the true meaning of ‘carbonaceous’ and ‘nitrogenous,’ so I will spare you my reflections on ‘sludge.’

In order for my water to be clean, it must be broken down to a molecular level, de-ionised, re-ionised, blessed by a bishop, and prayed over by a virgin.

However, I have identified two brands of bottled water which almost meet the standards which we must now demanded from natural sources: Tasmanian Rain ($11 a bottle), is captured from the ‘purest skies on earth,’ and doesn’t touch the ground before it gets to the bottle. Only problem is: what if a bunch of Aussies on stag-night fly a smoky old Cessna over the rain catchment facility? Perhaps better is 10 Thousand BC ($14 a bottle) – or the hippy’s dilemma, as I call it – because it’s extracted from a glacier and derives its purity from having been frozen since before the fall of man.

Or, of course, you could just give up drinking water, as I did years ago.

Marlow’s St Paul’s Capriccio

c. 1795; oil on canvas, 60 x 41 in.; London, Tate Gallery

The view of St Paul’s Cathedral as if it had been completed according to the original plans of Wren and with Hawksmoor’s baptistry (which I posted yesterday) reminded me of this capriccio by William Marlow. And then this in turn recalled my 2005 post If London Were Like Venice.

Little Ben

WALKING THROUGH Victoria recently, I was horrified to see the recent renovations and street improvements have led to the disappearance of ‘Little Ben’, the small Victorian clocktower that sat in a traffic island halfway between Westminster Cathedral and Victoria Station. Little Ben is a convenient meeting place in a district that is rather uninspiring and surprisingly lacking in conveniences.

WALKING THROUGH Victoria recently, I was horrified to see the recent renovations and street improvements have led to the disappearance of ‘Little Ben’, the small Victorian clocktower that sat in a traffic island halfway between Westminster Cathedral and Victoria Station. Little Ben is a convenient meeting place in a district that is rather uninspiring and surprisingly lacking in conveniences.

Why, for example, is there no decent pub in Victoria? If you need a meal, Grumbles of Pimlico is walking distance, and they treat you well at Il Posto. But a decent pub atmosphere is not to be had, unless you fancy The Pub Formerly Known as the Cardinal (now styling itself as ‘The Windsor Castle’).

Happily, a simple Google search reveals that Little Ben’s absence is merely temporary: indeed, Little Ben is taking a rest-cure. The goodly folk at Wessex Archaeology have informed us as such.

The clock owes its creation to Gillet & Johnston of Croydon, who built Little Ben in 1892 and erected it in the middle of Victoria Street. It fell victim to a road-widening scheme and was removed in 1964 but, after sitting in storage unappreciated for some years, it was finally renovated and restored to its original location in 1981.

Transport for London is currently working on a significant upgrade to Victoria Underground Station, including a rearranged traffic alignment on surface level, in addition to new entrances and exits and a great big whopping ticket hall sous la terre. When all is finished and done and in tip-top shape, Little Ben will be returned to his traditional location, and some semblance of order will return to this sector of the most unglamorous Victoria Street.

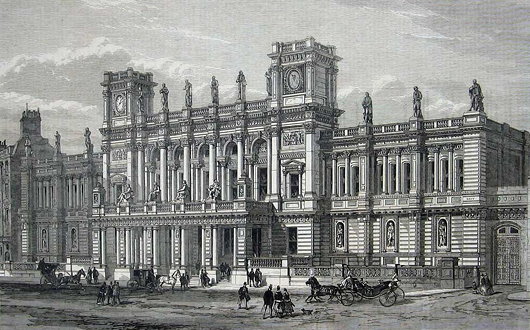

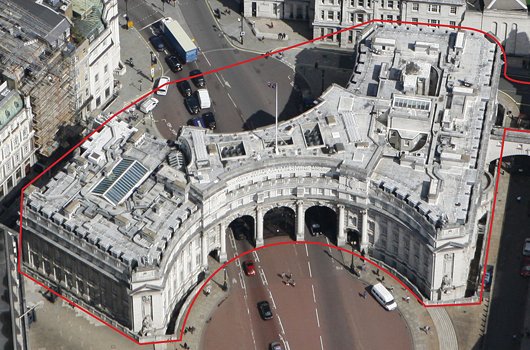

Admiralty Arch for Sale

Sort of: Queen Offers Long Leasehold of Edwardian London Landmark

SIR ASTON WEBB’S great Edwardian Baroque office-building-cum-triumphal-gateway, Admiralty Arch, will be offered up for a long leasehold by HM Government. The Grade-I listed building, constructed between 1910 and 1912, is one of the best-known in London for finishing the long view down the Mall from Buckingham Palace and connecting it to Trafalgar Square beyond. Admiralty Arch features 147,300 square feet across basement, lower ground, ground, and five upper floors.

Savills have been appointed as the sole exclusive agent to seek interest in the long leasehold. “The Government’s objective is to maximise the overall value to the Exchequer from the re-use of Admiralty Arch,” the Savills press release noted, “and to balance this with the need to respect and protect the heritage of the building, now and in the future, enable the potential for public access and ensure awareness of, and be prepared to respond to, potential security implications.”

Our prediction: oil money from abroad will turn it into a hotel. Boring, I know!

Comper in Clerkenwell

The unbuilt Church of St John of Jerusalem

IN THE REALMS of architecture, the unexecuted project has a certain air of fantasy to it — the allure of what might have been. Ranking high amongst my favourite unbuilt proposals is Sir Ninian Comper’s project for the Church of St John of Jerusalem at Clerkenwell. Comper designed the scheme in the middle of the Second World War as a conventual church for the Venerable Order of St John, the Victorian Protestant revival of the old Order of St John (now more commonly known as the Order of Malta) which was banished from England at the Reformation. The design (below) is a Romanesque-Gothic hybrid, a splendidly exuberant cross-fertilisation of two styles more frequently opposed to one another in the minds of most.

One of the proposals for the serious reform of the Order of Malta in Britain is for the Grand Priory of England to divest itself of its interest in the Hospital of St John & St Elizabeth and its associated chapel in St Johns Wood. Owing to a complicated series of events, conventual events are taking place at the Church of St James, Spanish Place already. As the Venerable Order never executed Comper’s brilliant design, perhaps the Order of Malta might consider buying a suitable site in London and making Comper’s fantasy a reality.

Cardinal Manning

Over at Reluctant Sinner, Dylan Parry has an excellent post on Cardinal Manning, the second man to serve as Archbishop of Westminster. Manning is all too often forgotten, despite being one of the most widely loved and respected men of his generation. His funeral, famously, was the largest ever known in the Victorian era. Besides his wisdom at the helm of England’s most prominent see, the good cardinal’s greatest legacy might be his influence on Rerum Novarum, the great social encyclical of Leo XIII. Dylan is planning on writing further on the subject of Cardinal Manning, giving us something to look forward to. (more…)

Begley Takes to the Skies

Brave Bear Skydives in Support of Hammersmith’s Irish Cultural Centre

The Irish Cultural Centre in Hammersmith, London is in danger of closing as its landlord, the local council, is putting the ICC’s building up for sale. The enterprising folk at the Centre have launched the Wear Your Heart for Irish Arts campaign to raise the funds required to save this outpost of Gaelry and have adopted Begley the Bear as the campaign mascot. Begley is a brave little lad and he recently undertook a charity skydive to raise money for the Centre.

Alright, he wasn’t so brave at first, but he worked up the courage in time.

The ICC’s assistant manager, Kelly O’Connor, accompanied Begley on his endeavour.

She had to cover poor Begley’s eyes at the start…

…but then they got into the swing of things.

And at the end of the day, who could say no to a pint of plain?

The Old In & Out

Cambridge House, Number Ninety-four, Piccadilly

ON MY WAY TO the Cavalry & Guards Club yesterday for lunch with an ancient veteran of King’s African Rifles (“Hardly qualify for this place — Black infantry!”) I realised I was a bit ahead of schedule and so took a gander at Cambridge House, the former home of the Naval & Military Club on Piccadilly. It’s surprising that an eighteenth-century grand townhouse of this kind has sat in the middle of the capital completely neglected, unused, and falling apart for over a decade.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories