London

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Pentonville Expressionism

When partner James Beazer of architectural firm Urban Mesh wanted to build an extension onto his Pentonville townhouse his tenderness towards brick expressionism took physical form.

“I love the work of the German Expressionists,” Beazer told the FT. “The playfulness of their use of brick. I think we’ve become uncomfortable with decoration today. Perhaps property has become too valuable. If it wasn’t, we’d all feel more able to take risks.”

Bringing brick expressionism down to a smaller scale produces interesting results here in Beazer’s case. It’s fun and somewhat slapdash — all the unconcerned confidence of an amateur delivered by a professional in his back garden. Hamburg meets the Shire in Islington.

I would have gently arched the windows, however, and the choice of lighting fixture is mundane. But it is a fundamental Cusackian principle never to let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

“I would probably have struggled to convince a client to do it,” Beazer says. But he has no confidence in the twisted brick add-on’s future once he moves house. “To be honest, the next people who move in will probably flatten it and replace it with a huge glass extension.”

The late Gavin Stamp gave an excellent lecture under the auspices of the Twentieth Century Society entitled ‘Hanseatic visions: brick architecture in northern Europe in the early twentieth century’.

It had been available online but now, alas, seems to be lost in the mists of time since the new incarnation of the Society’s website went up. Hope they stick it back online soon.

Onze Grootste President

The London Residence of President Martin van Buren

Transacting some business in March before the plague struck us here in London I found myself with a moment to spare and made a brief pilgrimage to No. 7, Stratford Place. It was in this handsome townhouse that Martin van Buren, the first New Yorker to ascend to the chief magistracy of the American Republic, had his residence when he served as the United States’s minister to Great Britain in 1831.

While I often claim that Calvin Coolidge was America’s greatest president in reality my chief devotion in that contest is to the Little Magician himself, the Red Fox of Kinderhook.

Among the many characteristics of this esteemed Knickerbocker is that English was not his native language and throughout his career as a democratically elected politician he spoke with a thick Dutch accent. To his wife, he spoke almost entirely in Dutch.

Jay Cost and Luke Thompson’s Constitutionally Speaking podcast at National Review recently released the first of a two episodes about van Buren and while I’m no fan of podcasts in general this was worth listening to.

One of the factors Cost and Thompson highlight is the utility of the party machine structures of the day in solidifying the practice of America’s democracy and acting as a vehicle of accountability, something too little appreciated by most later observers of the period.

We keen Kinderhookers and Van Buren Boys await the second instalment with anticipation.

Shamefully I have not yet made the pilgrimage to Kinderhook itself, but it’s pleasing to learn that the dominie of the Dutch Reformed Church is a graduate of the greatest university in the southern hemisphere.

A Chapel for Chernobyl

The Belarusian Church in London

Belarus was heavily affected by the disaster at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the neighbouring Ukraine back in 1986 when both countries were part of the Soviet Union. In the thirtieth anniversary year of that event, the Belarusian Catholic community in London dedicated a new chapel built to a striking modern design but evoking the folk churches of the old country.

Founded in 1947 as the White-Ruthenian Catholic Mission of the Byzantine-Slavonic Rite, the church grew out of the postwar migration to London of Belarusians who had served with the Polish army during the Second World War.

Succeeding the chapel of Sts Peter & Paul in Marian House, the new chapel is dedicated to St Cyril of Turau and All the Patron Saints of the Belarusian People.

In terms of church hierarchy, this mission is under the wing of the Ukrainian Catholic eparchy in Great Britain, part of the eastern-rite Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church which is in union with Rome. (more…)

A Corner in Camberwell

4a-6 Grove Lane by MATT Architecture

Alongside some of its neighbouring streets in Camberwell, Grove Lane has some of the best preserved rows of Georgian houses in south London, interspersed with a few buildings of a more recent vintage. The latest addition to this street is no ostentatious interloper but a contextual classic showing admirable humility and good manners.

Designed by Leicester Square-based MATT Architecture, it’s easy to see why the Georgian Group deemed 4a-6 Grove Lane worthy of a Giles Worsley Award for a New Building in a Georgian Context in 2015.

“The long, thin, wedge–shaped site had lain derelict for decades before being purchased by the current owner,” the architects note.

“The elevation is deliberately split into three to echo the plot width of neighbouring terraces and relies heavily on high quality detailing to lift it beyond pastiche.”

The Manor House

For devoted fanatics of Netherlandic architecture — I’m sure you’d count yourself as one as much as I do — a curious example of Dutch revival architecture can be found at No. 316 Green Lanes in the Borough of Hackney. Alighting from Manor House tube station the other day I was surprised to find myself confronted by a fine building which, it turns out, used to be the pub that gave its name to the Underground station.

The first ‘public house and tea-gardens’ of that name was built in the 1830s, and in 1843 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert stopped there for a change of horses. This tavern soldiered on until the arrival of the Piccadilly line which necessitated street widening and the demolition of the pub in 1930.

It was rebuilt in a very handsome brick Netherlandic revival in 1931 and continued on as a pub supplied by the London brewers Watneys.

A purist would object that the style of windows on the gables suggests a vulgar pakhuis (warehouse) on the Amstel while the stepped gable itself is more informed by domestic architecture. But is the privilege of architectural revivals to mix and match, so I don’t think we should complain.

Evidence suggests the pub shut in 2004 and the building was converted to its current retail use.

Alas, I can find no record of the architect, and the building remains un-listed, but I’m glad Hackney is home to this happy Hollandic interloper.

Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane still looms over the intervening centuries of architecture and design in Great Britain, but I’ve never actually known what he looked like. Apparently this is him, in an 1804 portrait by William Owen.

Everyone’s been to his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but Pitzhanger Manor, his place in the country (though Ealing hardly seems rural today) was recently reopened after serious conservation works ongoing since 2015.

Hope to pay it a visit soon.

Soho Iridescent

Stiff & Trevillion’s 40 Beak Street in London

Beak Street in London is teeming with turquoise iridescence since the completion of a new office building by the architectural firm of Stiff & Trevillion earlier this year. A joint project between property investment companies Landcap and Enstar, Number 40 Beak Street has been purchased for £40 million by Damien Hirst — the canny businessman who sells dead animals in formaldehyde glass boxes. The over-27,000-square-foot building will serve as the primary London studio for Hirst and headquarters for his company, Science (UK) Ltd, in addition to housing a restaurant at ground level.

Five storeys tall, 40 Beak Street features a number of roof terraces in addition to cornice work designed by Hertfordshire-based artist Lee Simmons. The glazed bricks — “hand dipped” the architects tell us — make for a welcome change from the omnipresence of metal and glass on one end of the spectrum and cheap monotone brick on the other.

The PR hype makes much of bringing a bit of artistic and creative edge back into Soho, a neighbourhood whose final glory days have been depicted in a much-praised book by the Telegraph’s Christopher Howse. We’re not so sure.

Hype aside, 40 Beak Street is an excellent addition to the London landscape and the designers are to be commended for their fine eye for detail. Someone at Stiff & Trevillion knows what they’re doing.

Holborn Town Hall

The Metropolitan Borough of Holborn was the smallest borough of London both in geography and population so perhaps it’s not surprising that its town hall was a pretty but rather humble affair. The civic pride and municipal pomposity for which this realm was once renowned are nowhere on show in this handsome building which, but for a few details, could easily be mistaken for a hotel, office building, or private residences.

Holborn Town Hall was built in stages, with the public library on the left-hand side completed in 1894 by the Holborn District Board of Works to a design by Isaacs. With the erection of the borough in 1900, a town hall was needed, and the central and right-hand sections of the building were added between 1906 and 1908 by the architects Hall & Warwick.

In 1965 the borough was merged with St Pancras to form the new London Borough of Camden. It was decided to consolidate the civic government at St Pancras Town Hall, to which the local government union members objected. To placate their ire, a bar for the use of employees was erected atop the annexe being added to the Camden (ex St Pancras) Town Hall — quickly nicknamed ‘the White Elephant bar’.

Though long sold off and converted into office space, the arms of the old borough of Holborn still grace the first floor balcony.

The Port of London

Officially there are or have been various Londons: first the City of London, founded in AD 43 and a mere square mile to this day, then the County of London created in 1889, and the creature called Greater London has also existed in varying shapes and forms since 1965.

But there is also the Port of London, which has existed since the first century and was once the busiest port in the world, bringing the riches of empire to the metropolis from the four corners of the earth.

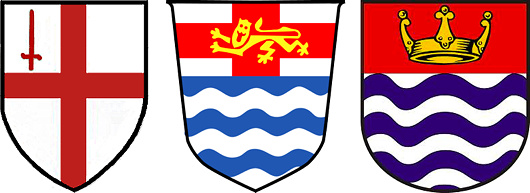

The arms of the City of London, London County Council, and Greater London Council.

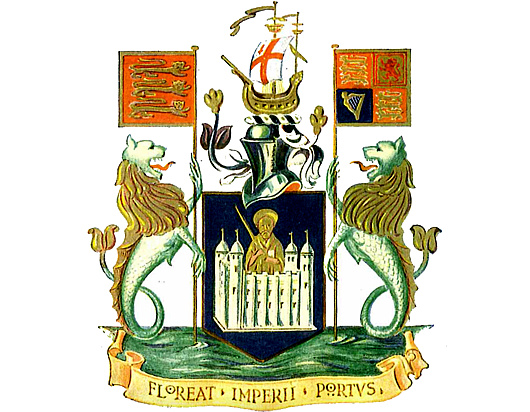

All these Londons, of course, have over the centuries been granted or assumed their own coats of arms as heraldic emblems of their importance. The Port of London Authority was created in 1908 by an Act of Parliament which some scholars argue is the first law in the world mandating codetermination or workers’ participation in the board.

Its coat of arms was granted a year later in 1909 and features on its shield Saint Paul, the patron saint of London bearing his usual sword, issuing forth from the Tower of London.

Its coat of arms was granted a year later in 1909 and features on its shield Saint Paul, the patron saint of London bearing his usual sword, issuing forth from the Tower of London.

The crest above the shield is a galley bearing on its mainsail the arms of the City of London — the Lord Mayor is ex officio the Admiral of the Port of London.

Sea lions act as supporters, also bearing standards of the royal arms of England and of the United Kingdom, while the motto proclaims in Latin May the Port of the Empire Flourish.

For proper heraldry nerds, the arms are blasoned:

Shield: Azure, issuing from a castle argent, a demi-man vested, holding in the dexter hand a drawn sword, and in the sinister a scroll Or, the one representing the Tower of London, the other the figure of St Paul, the patron saint of London.

Crest: On a wreath of the colours, an ancient ship Or, the main sail charged with the arms of the City of London.

Supporters: On either side a sea-lion argent, crined, finned and tufted or, issuing from waves of the sea proper, that to the sinister grasping the banner of King Edward II; the to the sinister the banner of King Edward VII.

Befitting the Port of the Empire, the Authority built a grandiose headquarters at 10 Trinity Square, overlooking the Tower of London featured in its coat of arms.

The PLA moved out ages ago and the building is now a hotel, but it often features in films and television as a government (most prominently in the 2012 James Bond film ‘Skyfall’).

The Port of London Authority has its own flag (above) as well as its own ensign — a blue field with a Union Jack in the canton and in the fly a golden sea lion bearing a trident. Distinctive pennants also exist for the Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Authority. (These can be seen here.)

After its foundation the PLA rationalised the layout and organisation of London’s dock system, and their significant constructions allowed the Port to displays its arms on numerous buildings. One such display (above) was recently sold by Westland London.

The main shipping terminal of London is now far down-river at Tilbury and the Authority no longer owns any docks. Its duties however are still numerous — control of Thames ship traffic, navigational safety, pier & jetty maintenance, and conservation — so the century-old Authority still keeps itself quite busy looking after a millennia-old port.

St Paul’s Survives

Crossing the Thames as I walked home from the pub last night, I looked down the river and saw the sturdy dome of St Paul’s standing out, illuminated in the winter night.

As it happens, it was exactly seventy-seven years ago last night — on the 29th of December 1940 — that the iconic photograph often called ‘St Paul’s Survives’ (above) was captured.

Hopeful as that sight must have been, it was a pretty grim time. But four and a half years later (below) the cathedral was illuminated not by the lights of enemy firebombs but by great searchlights forming a massive ‘V’ in the sky: it was 8 May 1945 — Victory in Europe.

Another year gone. We’ve survived.

Warwick Street Church

Over in Soho there is a curious little church with a fascinating history. The parish of Our Lady of the Assumption & St Gregory in Warwick Street started out as the house chapel for the Portuguese embassy in Golden Square, later occupied by the Bavarian embassy.

In recent years the Archdiocese of Westminster has placed the church in the care of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, and they have put new life into the strong musical tradition of the parish.

As chance would have, in my capacity as a professional web designer I was commissioned to design a new website for the parish.

You can view the new Warwick Street website here, and read a little more about its interesting history and architecture.

Physical Energy

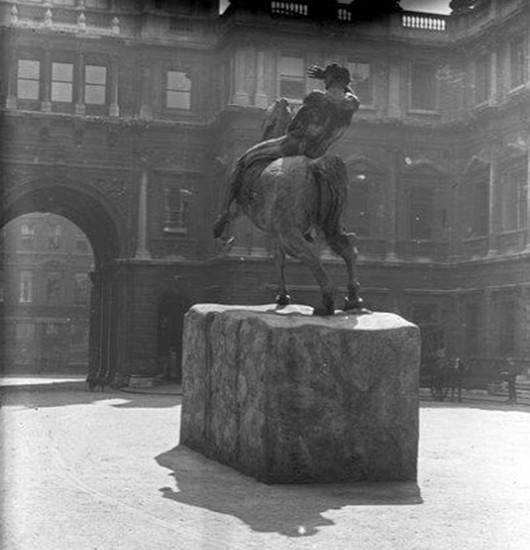

I came across it by surprise one day, walking through the park. It was almost eerie — all the more so for being unexpected. George Frederic Watts’s sculpture “Physical Energy” was well known to me when I lived in South Africa as it graces the Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town — a rough Greek temple staring out northwards into the vast continent of Africa, as Rhodes himself liked to do.

Unknown to me, another cast of the statue was made and given to the British government, which placed it in Kensington Gardens. It was this copy I stumbled upon while traversing the park to Lily H’s drinks party in the garden of Leinster Square.

It is one of the most aptly named sculptures I can think of, as there is a raw brutish physicality to it, and somehow a sense of tremendous force, power, and energy. Watts was primarily a painter, so that he achieved this great work of sculpture is all the more remarkable. I don’t actually like it: there is something uncomforting and almost vulgar about it, or perhaps just taboo. (Like Rhodes himself.) But it is amazing all the same.

While “Physical Energy” is primarily associated with Cecil Rhodes it was not commissioned in his honour. Watts conceived it in 1886 after having done an equestrian statue for the Duke of Westminster. The first cast wasn’t made until 1902 and was exhibited at the Royal Academy for the first time in 1904 (above).

From there it made its way to Cape Town where it stands today a vital component of the monument to Rhodes. (It even features as the crest on Rhodes University’s coat of arms.) The second cast from 1907 is this one that sits in Kensington Gardens, while a third cast from 1959 now sits beside the National Archives of Zimbabwe in Harare.

This year the Watts Gallery in Surrey commissioned a fourth cast to commemorate the two-hundredth anniversary of the artist’s birth — and that cast now flaunts its bronze in the courtyard of the Royal Academy. It remains on view until the Cusackian birthday in March 2018.

Pimlico Forever – Belgravia Never!

It started with hints and rumours, ill-whispered talk on street corners and tiny little changes, but now it’s all gone too far. You see, Pimlico, the quarter of London in which I dwell, seems under threat of annexation by its far grander but past-its-prime neighbour Belgravia.

It all seemed quite amusing at first. One day I came home to our humble address in Pimlico and was surprised to find the Belgravia Residents Journal amongst our post. Then Tatler nailed its colours to the mast and claimed the Italian coffee shop on our Pimlico street corner is in Belgravia. I went to my bank branch the other day to sort out a minor matter of travel insurance only to notice ‘Belgravia branch’ spelled out in clear concise Helvetica letters. Was that always there? I wondered.

Residents are befuddled and confused for the most part. No one’s quite sure what’s going on. Memories of “Passport to Pimlico” are exchanged — “Blimey! I’m a foreigner!” Concerns that Cambridge Street Kitchen (or at least its Cocktail Cellar) may be in on the move. “Isn’t this place a bit Elizabeth Street?” she said, sipping a Mexcal Negroni.

Landlords in particular are viewed as being suspiciously complicit in Belgravian expansionism. It’s widely assumed that speculators are keen to turn our beautiful whitewashed Pimlico homes (most of them long since divvied into flats) into the embassies, cultural institutes, and the bland organisational headquarters for which Belgravia is known.

“Do you think we’ll get some embassies after we join Belgravia?” one resident asks. Another points out we already host three: Lithuania, Albania, and Mauritania. “Perhaps we could get Sweden. Do you think we could get Sweden?” No one seems to know.

Some pooh-pooh the entire idea as hyped-up nonsense. “What on earth would Belgravia want from us here in Pimlico? Her Majesty’s Passport Office? The Queen Mother Sports Centre? The Catholic Bishops Conference? The flippin’ UK Statistics Authority?” (I admit, I had no idea the UK Statistics Authority is based here in Pimlico.)

Others prepare for collaboration. “We’ve always considered this Lower Belgravia,” Dr O’Donnell says with a wry smile.

Still, there is talk of resistance. Estate agents have reportedly been threatened with the use of force by mysterious figures in black cagoules. Suggestions of pre-emptive action, or recourse to the Court of Justice in Strasbourg. Should we strike first? Enclaves of Pimlico the other side of Buckingham Palace Road, like the pool hall in Ebury Square, could be used as springboards for a more active approach. The Filipino ladies in the Padre Pio shop on Vauxhall Bridge Road seem blissfully unaffected.

Confusion reigns, uncertainty is rampant, no one knows what the future holds.

Hoarding has commenced and local shops are quickly selling out of useful products (bog roll, Pringles, gin, etc.).

From St George’s Square to Victoria Station, fear grips the streets. At least its stopped people talking about Brexit.

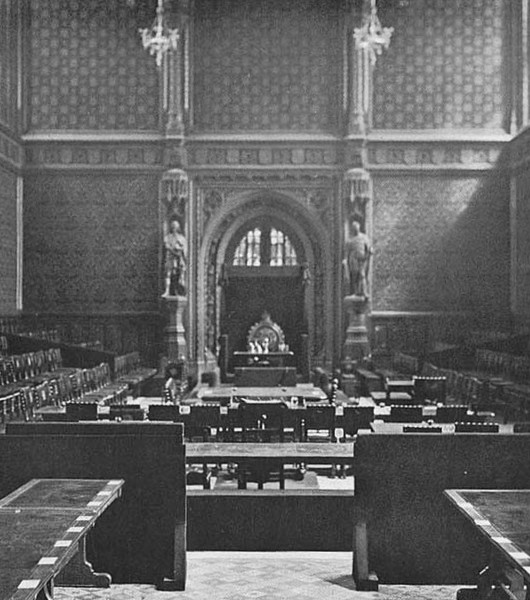

Justice in the Royal Gallery

One of the great triumphs of Magna Carta was the assertion of the right of those accused of crimes to trial by one’s peers, or per legale judicium parium suorum if you insist on the Latin. For commoners this meant trial by other commoners, but for peers it meant just that: trial by other peers of the realm. It was a bit murkier for peeresses, though after the conviction for witchcraft of Eleanor, Duchess of Gloucester, (sentence: banishment to the Isle of Man) statute was passed including them in the judicial privilege of peerage.

Thanks to the ’15 and the ’45, there were a number of trials in the House of Lords in the eighteenth century, including that of the Catholic martyr Earl of Derwentwater. The whole of the nineteenth century, however, witnessed but one: the 7th Earl of Cardigan was acquitted of duelling by a jury of 120 peers. In 1901 the 2nd Earl Russell was found guilty of bigamy, and the last ever trial came in 1935 when the 26th Baron de Clifford was found not guilty of manslaughter.

Cardigan’s trial was in the temporary Lords chamber while the last two trials took place in the Royal Gallery of the Palace of Westminster (central to current debates over renovation plans). For Cardigan’s trial the Lord Chief Justice of the Queen’s Bench was appointed Lord High Steward for the occasion, while for the final two the Lord Chancellor was likewise appointed to the role in order to be presiding judge with the Attorney General prosecuting the case.

The Royal Gallery is primarily used for the State Opening of Parliament (as above) and for the occasional address to both Houses of Parliament when important figures are invited to do so. De Gaulle was famously invited to speak here to both houses rather than in the larger Westminster Hall. It is thought that this is because the walls of the Royal Gallery feature two large murals, one of the Battle of Trafalgar, the other of the Battle of Waterloo – both British victories over the French.

The most famous trial in the Royal Gallery was fictional. In the 1949 Ealing comedy “Kind Hearts and Coronets”, the 10th Duke of Chalfont is tried for the one murder in the film’s plotline he didn’t actually commit. Ealing Studios did a mock-up of the chamber for the occasion (above), which compares reasonably accurately with the Royal Gallery as set up for the Baron de Clifford’s trial in 1936 (below).

The Lords, however, were uncomfortable with exercising this judicial function and passed a bill to abolish the privilege in 1937. The Commons, facing more serious tasks, declined to give it any attention. In 1948, the Criminal Justice Act abolished trials of peers in the House of Lords, along with penal servitude, hard labour, and whipping.

Challoner’s House

Challoner’s House — Rather humble for an episcopal palace, but such was the function of No. 44, Old Gloucester Street in Holborn during the time of Bishop Richard Challoner.

If it seems an odd spot for London’s Catholic bishop, it can be explained by its close proximity to the chapel of the Sardinian Embassy off Lincoln’s Inn Fields. At this time, of course, the Mass was still illegal and the only places Catholics in London could worship were the embassies of the Catholic nations. To protect the underground bishop, the house in Old Gloucester Street was actually rented in the name of his housekeeper, Mrs Mary Hanne.

After a perfect breakfast on Saturday morning the sun was shining so I decided the three-and-a-half miles home from St Pancras were best managed on foot. If architectural or historical curiosities are your fancy then foot is the way to travel, and so it was by pure chance that I stumbled upon No. 44. It seemed particularly appropriate that the night before a whole gang of us — Brits, Swedes, Italians, etc. — had been drinking in the Ship Tavern in Holborn where Bishop Challoner was known to offer the occasional clandestine Mass. (more…)

Holy Trinity Kingsway

Holy Trinity, Kingsway

Not much information is available about this church. The architect was John Belcher but the ambitious tower was never built, nor was there much money to complete the interior.

After it was made redundant in the 1990s the church was demolished — except for the façade so obviously influenced by Santa Maria della Pace.

Floating an Idea for Parliament

Members of Parliament are currently battling one another over plans for the ‘restoration and renewal’ of the Palace of Westminster. One side, backed by management consultants and the Joint Committee report, say the whole place has to be shut down completely for years starting in 2020. The other, led by Sir Edward Leigh MP and Shailesh Vara MP, says if work is so urgent it should start immediately, but that both the Commons and the Lords should continue to meet within the Palace, preserving centuries of tradition and keeping up the dignity and ceremony for which Great Britain is known.

With ideas flowing back and forth, outsiders to the Westminster bubble have put forth their own ideas — the architect Anthony Delarue’s suggestion has received the most serious consideration so far — and the global design firm Gensler has weighed in with its own proposal.

Gensler’s idea calls for a floating slug bearing a distinct resemblance to the Gherkin to be built and moored alongside the Palace of Westminster. This floating parliament would have plenary chambers for both the House of Lords and the House of Commons as well as committee rooms and other meeting places necessary to the functioning of the legislature.

While it’s a serious idea, the floating slug is not under actual consideration but is merely a conceptual exercise put out there by Gensler. Security concerns alone would lead to its rejection, not to mention worry over the hole in the historic fabric that would need to be punched through in order to access the slug. (more…)

Church of St James, Spanish Place

Always interesting to see a building you know well from a perspective you’ve never seen before, as in this photo of the Church of St James, Spanish Place, taken from Manchester Mews. The church somehow seems more imposing — like a great rounded keep.

A few months ago I was corralled into some favour or other that required a bit of muscle to move this there and whatnot, the payoff of which was it afforded an opportunity to explore the triforium of this Marylebone church and see the interior of the building from an entirely new vantage point.

It also meant being able to view in better detail the beautiful stained glass windows — many of them the gift of various Spanish royals, given that this parish originates as the chapel of the Spanish embassy (hence its name).

Johannes Kip’s View of London

View and Perspective of the City of London, Westminster, and St James’s Park

This view of London and Westminster is most notable for the unique perspective it takes: a bird’s eye view from above the Duke of Buckingham’s house, later acquired by the Crown and now, as Buckingham Palace, the primary royal residence.

This printing of Kip’s view, which comes up for auction soon at Daniel Crouch Rare Books, may have been printed after 1726 as it incorporates Gibb’s steeple of St Martin-in-the-Fields.

St Pancras Town Hall

St Pancras Town Hall is an interwar classical building by the architect A.J. Thomas (of whom I know little). The façade is a little clunky but in the warmer months it’s adorned with arrangements of flowers that soften this stern civic edifice with a bit of welcome frivolity.

When the Metropolitan Borough of St Pancras was merged with the neighbouring bailiwicks of Hampstead and Holborn to form the London Borough of Camden in 1965 this was chosen as the town hall of the new entity, so it’s now referred to as Camden Town Hall.

But of course of all the buildings under the patronage of the fourteen-year-old, fourth-century martyr Pancras, the most prominent is the international railway station across the Euston Road (below) that connects this metropolis with the rest of the continent across the Channel.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Image: © HughJLF

Image: © HughJLF Image: © Stephen Benton

Image: © Stephen Benton Image: © Stephen Benton

Image: © Stephen Benton