Literature

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Articles of Note: 13 March 2024

My then-flatmate was getting married the next day and much pottering-about sorting things was required but the idiosyncratic beauty of this building captured my imagination — part Norman, part Moorish. I was almost insulted that I hadn’t come across it in any of my bookish explorations.

The historian Edmund Harris covers Chideock in his lusciously illustrated post on Recusancy in Dorset and the ‘other tradition’ of Catholic church-building.

■ Generations ago it was said that the three institutions no British politician dared offend were the trade unions, the Catholic Church, and the Brigade of Guards. In 2020s Britain there is only one caste which must always be obeyed: the ageing, moneyed homeowners.

Not only do these “NIMBYs” (“Not In My Back Yard”) jealously guard their freeholds, they do whatever they can to prevent more houses being built to guard the value of their prize possessions, vastly inflated by a combination of lacklustre housebuilding and irresponsible leap in migration. As old people vote and young people don’t — and when they do, vote badly — few sensible people can find a way out of this quagmire.

It might be worth looking to the Mediterranean, where Tal Alster tells us How Israel turned urban homeowners into YIMBYs.

■ It’s disappointingly rare to see intelligent outsiders give a considered impression of the current state of play in the Netherlands — that’s Mother Holland for us New Yorkers. Too often commentators in English are either rash cheerleaders for the hard right or bien-pensant liberals eager to castigate and chastise. Both rush to judgement.

What a rare diversion then to read Christopher Caldwell — the only thinking neo-con? — attempt to explore and explain the success of Geert Wilders in the recent Dutch elections.

■ One in ten of Lusitania’s inhabitants are now immigrants, and this discounts those — many from Brazil and other former parts of the once-world-spanning Portuguese empire — who have managed to acquire citizenship through various routes.

Ukrainian number-plates are now frequently be seen on the roads of Lisbon, as far in Europe as you can get from Big Bad Uncle Vlad.

Vasco Queirós asks: Who is Portugal for?

■ Speaking of world-spanning empires, in true andrewcusackdotcom fashion, we haven’t had enough of the Dutch — but we have had enough of their wicked wayward heresies.

Historian Charles H. Parker explores the legacies of Calvinism in the Dutch empire.

■ The City of New York itself is the best journalism school there is. Jimmy Breslin dropped out of LIU after two years, eventually taking up his pen. Pete Hamill left school at fifteen, apprenticed as a sheet metal worker, and joined the navy.

William Deresiewicz argues that a dose of working-class realism can save journalism from groupthink.

■ The New Yorker tells us how a Manchester barkeep found and saved a lost (ostensible) masterpiece of interwar British literature.

■ Our inestimable friend Dr Harshan Kumarasingham explores David Torrance’s history of the first Labour government on its hundredth anniversary.

■ And finally, one for nous les normandes (ok, ok, celto-normandes): Canada’s National Treasure David Warren briefly muses that the Norman infusion greatly refined Anglo-Saxon to give us the superior English tongue we speak today.

The Headless Horseman & Hallowe’en

Washington Irving’s Legend of Sleepy Hollow — perhaps better known as the tale of the Headless Horseman — is inevitably and almost universally linked to the great feast of Hallowe’en.

There are obvious reasons for this in that Hallowe’en has become the festival of ghoulish otherworldliness, sadly now devolved into plastic mawkishness in a manner old followers of the Knickerbocker ways must surely condemn and mourn.

But this tale is always worth a revisiting; even now in early Advent.

Irving purists — we exist — might point out there there is no indication Ichabod Crane’s fateful evening ride through the Hollow took place on Hallowe’en.

Indeed, Hallowe’en is not mentioned at all in the text of the Legend, and all the author shares with us regarding the date is that it was “a fine autumnal day”:

…the sky was clear and serene, and nature wore that rich and golden livery which we always associate with the idea of abundance.

The forests had put on their sober brown and yellow, while some trees of the tenderer kind had been nipped by the frosts into brilliant dyes of orange, purple, and scarlet.

Streaming files of wild ducks began to make their appearance high in the air; the bark of the squirrel might be heard from the groves of beech and hickory-nuts, and the pensive whistle of the quail at intervals from the neighboring stubble field.

It makes for a luscious harkening of old Westchester and the Hudson Valley in the early days of the republic.

Tastier still is the scene set as the Yankee newcomer Crane enters the home of an old Dutch household for the evening’s revelries:

Fain would I pause to dwell upon the world of charms that burst upon the enraptured gaze of my hero, as he entered the state parlor of Van Tassel’s mansion.

Not those of the bevy of buxom lasses, with their luxurious display of red and white; but the ample charms of a genuine Dutch country tea-table, in the sumptuous time of autumn.

Such heaped up platters of cakes of various and almost indescribable kinds, known only to experienced Dutch housewives!

There was the doughty doughnut, the tender oly koek, and the crisp and crumbling cruller; sweet cakes and short cakes, ginger cakes and honey cakes, and the whole family of cakes.

And then there were apple pies, and peach pies, and pumpkin pies; besides slices of ham and smoked beef; and moreover delectable dishes of preserved plums, and peaches, and pears, and quinces; not to mention broiled shad and roasted chickens; together with bowls of milk and cream, all mingled higgledy-piggledy, pretty much as I have enumerated them, with the motherly teapot sending up its clouds of vapor from the midst—Heaven bless the mark!

I want breath and time to discuss this banquet as it deserves, and am too eager to get on with my story.

Happily, Ichabod Crane was not in so great a hurry as his historian, but did ample justice to every dainty.

So celebrate Hallowe’en not with plastic costumes and cheap trinketry but with Dutch delicacies and tasty treats. (And for helpful suggestions, see Peter G. Rose’s Food, Drink, and Celebrations of the Hudson Valley Dutch.)

Put aside the vampire capes and risqué nurses’ kit and, amidst candles and pumpkins of all shapes and sizes, think of the Dutch Hudson of long ago that lingers still in heart and mind.

Ödön von Horváth

When the shop purveying diacritical marks opened one morning in Vienna, in my mind the writer Ödön von Horváth turned up and said “Thanks. I’ll have the lot.”

It wasn’t even his real name, of course — which was Edmund Josef von Horváth. A child of the twentieth century, von Horváth was born in Fiume/Rijeka in 1901. His father was a Hungarian from Slavonia (in today’s Croatia) who entered the imperial diplomatic service of Austria-Hungary and was ennobled, earning his “von”.

“If you ask me what is my native land,” von Horváth said, “I answer: I was born in Fiume, grew up in Belgrade, Budapest, Preßburg, Vienna, and Munich, and I have a Hungarian passport.”

“But homeland? I know it not. I’m a typical Austro-Hungarian mixture: at once Magyar, Croatian, German, and Czech; my name is Hungarian, my mother tongue is German.”

From 1908 his primary education was in Budapest in the Hungarian language, until 1913 when he switched to instruction in German at schools in Preßburg (Bratislava) and Vienna.

Von Horváth went off to Munich for university studies — where he began writing in earnest — but quit midway through and moved to Berlin.

He once told his friends the story of when he was climbing in the Alps and stumbled upon the remains of a man long dead but with his knapsack intact.

Intrigued, he opened the knapsack and found an unsent postcard upon which the deceased had written “Having a wonderful time”.

“What did you do with it?” his friends naturally inquired. “I posted it!” was von Horváth’s reply.

In 1931 he was awarded the Kleist Prize for literature, but two years later the National Socialists took the helm and von Horváth thought it best to move across the border to his old imperial capital of Vienna.

Despite his anti-nationalism, he did initially join the guild for German writers set up by the Nazis, possibly to keep his works in print in the Reich while he was living in still-independent Austria.

It was in Vienna he published his best-known work: Jugend ohne Gott — “Youth without God” (first translated into English as The Age of the Fish), which marked his public point-of-no-return break with the Hitlerites.

The novel depicts a jaded schoolteacher increasingly disconnected from his profession and the world around him as the ideology of National Socialism begins to take root in the education system. (Bizarrely, it was also scantly used as the basis for a 2017 dystopian thriller.)

When Hitler’s troops marched into Austria the following year, von Horváth fled to Paris.

“I am not so afraid of the Nazis,” he told a friend there one day. “There are worse things one can be afraid of, namely things you are afraid of without knowing why. For instance, I am afraid of streets. Roads can be hostile to you, can destroy you. Streets frighten me.”

Days later, in the middle of a thunderstorm, von Horváth was walking down the Champs-Élysées — the most famous street in Paris — when a flash of lightning struck a tree, felled a branch, and struck the writer dead. He had been on his way to the cinema to see Walt Disney’s ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’.

Years ago someone recommended The Eternal Philistine: An Edifying Novel in Three Parts to me, but I have to admit I haven’t yet read it, or much else of von Horváth’s work. (He’s on my fiction wish-list though.)

His plays have been revived, too — here in London at the Almeida and the Southwark Playhouse in the past decade or so — and both The Eternal Philistine and Youth Without God are available in English from the estimable Neversink Library imprint of Melville House.

What Huxley’s Got on Orwell

Comparing dystopic visions of the English twentieth century

by ALEXANDER FRANCIS SHAW

Aldous Huxley wasn’t as good a writer as George Orwell but in several ways his Brave New World exceeds the prescience of 1984.

Huxley understood how society would respond if the laws of human ecology were to change. In a mechanised age, useless activity would become a necessity, while medical revolution and sexual deregulation in turn become the germ of totalitarianism. Orwell and just about everyone else since have had the opposite idea – that the libertines would be the liberators – and the fever-pitch of this very delusion forms the central tenet of Huxley’s dystopia.

Both visionaries describe state censorship, but in Huxley’s Brave New World one recognises eery pre-echoes of ‘Woke culture’ in an opiate-addled society which has to conceal its operational ethos from its own general consciousness in order to keep itself functioning smoothly.

With Orwell – the human struggle is represented as Man versus The State. Huxley recognised, as we are now encouraged not to, that society is the product of biology and, provided that people’s biology can be conditioned correctly, the state can foster grass-roots totalitarianism without the use violent coercion.

Neither dystopia has been fully realised – but in Orwell’s case this has been because progress has provided its own remedies (nobody could have imagined in the 1940s that telescreens would also be a conduit of private interaction for dissenters’ online discourse). One gets an unsettling feeling that Huxley’s medical dystopia is still developing in 2021 with no solutions in sight.

Rather than solve the riddle of human happiness, the citizens of Brave New World condemn those who fail to gloss over their displeasure with life through the mollifying comforts of sex and tranquillisers. Science becomes a branch of pragmatism, wielded by social engineers who can no more observe their own fields than look at their own eyeballs.

We are left with the question of how an outsider, possessed of higher directives than his own hedonism, might react to such a society?

Huxley answers this by introducing a Linda and her son, John, who live in a ‘savage reservation’ where medical advances have not been imposed. Traditional sexual morality is thus observed by the occupants along with – shudder! – family life and religious practices and other pursuits which lend meaning to their backward lives.

Linda arrived in the reservation by accident, having been born and acculturated in the ‘civilised world.’ She teaches her son how to read, but brings them both into disgrace with her promiscuity, so that John retreats into the comforts of a book which happens to be ‘The Complete Works of William Shakespeare.’ In Shakespeare, John finds the words that enable him to assert himself both on the reservation and – to the curiosity of his minders – when he finally returns to civilisation.

I sense that Orwell would have furnished John with a lowlier reference-point to human nobility and driven the same points home more poignantly with a dog-eared copy of Paris Match. But, as I said, Huxley was a better visionary than he was a wordsmith.

Once in the ‘civilised world’ John falls in love and faces a problem which, less than a century after Huxley’s work was published, defines what is perceived as a ‘crisis of masculinity’: how to court a woman who gives herself out to dozens of men regardless of merit. Unable to disabuse himself of his chivalric values – and unwilling to accept her worthless sexuality when she freely offers herself to him – John becomes what we would now call a proto-“incel” and dies, as the carnal realists of the toxic chatrooms might anticipate, on the end of a rope.

Smokescreens of happiness and delusion are maintained with a tranquilliser called Soma. Much as anti-depressants are a major feature of modernity – their use strongly suggesting that they are employed where artificial economies and casual sex are normalised – one senses that we have not yet perfected the Brave New World’s capacity for total bafflement. Nor has any welfare state or medical advancement completely collectivised the process of raising children.

This tranquillised social order is upheld by World Controller Mustapha Mond, Huxley’s benign analogue to Orwell’s Big Brother and on that account one of the few people in this dystopia who has achieved any kind of true satisfaction himself. Mond’s discourses bring Huxley to the place of scientific observation in the stable technological order:

‘once you start admitting explanations in terms of purpose – well, you don’t know what the result might be…’

In other words: Heaven forbid anyone should question the dogmas of settled science.

In terms of who may be allowed to see through the delusion, Mond likens the social hierarchy to an iceberg – with 10 per cent above the surface and 90 per cent below. Maverick, enquiring minds must either be sent to isolated communities or – like himself – shoulder the burden of everyone else’s delusion.

Despite Orwell’s predictions of people cowering under state tyranny and violence, Huxley’s work remains the creepier for its ability to get under the skin of the liberal society that we find familiar.

How much worse is it to read of a dystopia in which, by our own liberated will, we are complicit?

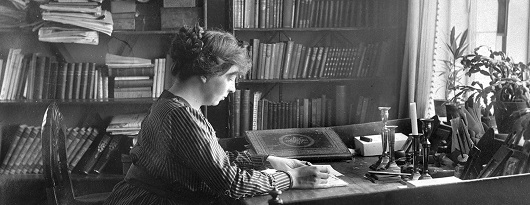

Understanding Undset

Sigrid Undset’s is doubtlessly among the twentieth century’s greatest writers, even though Kristin Lavransdatter, her main works of literature, is set in the fourteenth century. At the ceremony awarding Undset the 1928 Nobel Prize for Literature, Per Hallström described the writer’s narrative as “vigorous, sweeping, and at times heavy”:

It rolls on like a river, ceaselessly receiving new tributaries whose course the author also describes, at the risk of overtaxing the reader’s memory. […] And the vast river, whose course is difficult to embrace comprehensively, rolls its powerful waves which carry along the reader, plunged into a sort of torpor. But the roaring of its waters has the eternal freshness of nature. In the rapids and in the falls, the reader finds the enchantment which emanates from the power of the elements, as in the vast mirror of the lakes he notices a reflection of immensity, with the vision there of all possible greatness in human nature. Then, when the river reaches the sea, when Kristin Lavransdatter has fought to the end the battle of her life, no one complains of the length of the course which accumulated so overwhelming a depth and profundity in her destiny. In the poetry of all times, there are few scenes of comparable excellence.

Obviously Kristin Lavransdatter must be read for itself. I started reading it in the Stellenbosch University library a decade ago and was able to finish it thanks to being given a copy by a kindly Premonstratensian.

But the woman behind Kristin wrote more: her biographical essays and other works (like the one describing a visit to Glastonbury) are just as enjoyable and insightful.

At First Things, Elizabeth Scalia describes Undset’s lives of saints and holy men and women in Sigrid Undset’s Essays for Our Time.

Stephen Sparrow reveals much of Undset’s own biographical detail and how this influenced her writing in Sigrid Undset: Catholic Viking.

But the best essay I’ve read on Sigrid Undset so far is David Warren’s meditation on womanhood, motherhood, and Kristin Lavransdatter. I don’t agree with everything he says (I rather enjoyed the new translation but am thinking I might have to give the old one a go), but David gets Kristin the character, gets Kristin the novel, and gets the way that life is refracted through both.

Read David Warren, then read Sigrid Undset.

Some reading notes

ROBERT O’BRIEN, IN a deliberately provocative gesture, once said in conversation that he pitied America for not having any literature. Preposterous! was my natural response. We have Chaucer and Shakespeare and Mallory and Dickens! Yes, you Britons have them too, but you will have to share, I’m afraid. To try to separate America from the English greats is the equivalent of forbidding a son from taking pride in his family’s long and illustrious history. He may not be the eldest male descendant, but does this mean he must deny his heritage? Of course not. Naturally, like the Scots and the Irish we have our own subset of English literature — Mark Twain, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Flannery O’Connor, and J.D. Salinger come to mind — and there are even a few crossovers such as Henry James and T.S. Eliot.

The idea of doing a degree in English or in any literature has always seemed unattractive to me, though I by no means advocate the abolition of English departments. Perhaps it’s because I rarely found English a compelling subject in high school, though I did have some extremely talented teachers: The P (as she is known), as well as Mr. Leahy. I am one of those no doubt millions who wishes he had actually read all those books he supposedly read for class at school. I did enjoy Sophocles, and Homer too, but I did not really get into Flaubert (I intend to revisit him). Crime and Punishment I soaked up at the time, but have since forgotten.

How tiresome it must be, as a formal student of literature, to be forced to answer questions about works you have read. I wonder if there should be two tracks within universities: one for gentlemen, who merely seek to learn, and another for budding academics, who need proof they’ve learnt something. Some books have taken years (and multiple readings) to truly sink in, so it seems preposterous to arbitrarily require a succinct series of answers to examination questions at the end of a term.

Idea-driven novels seem foolish to me as well. In New York, I knew a Frenchman, not much older than myself, who (I discovered) was in the midst of writing a novel. Intrigued, I asked him one day what the novel is about. He paused for a few moments, sat back, and slowly tapped his finger thrice on the table in thought, and said “Stratification”. Well! Call me a simpleton but I would have preferred “a guy, a girl, a plot, an affair, schoolmates, a day, a week . . .” anything, but “stratification”?

Well, he is writing in French, and if you are going to write an idea-driven novel, it’s probably best to do it in French.

What have I been reading lately? A few months ago I finished Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands — an absolutely cracking book. It was late in the African summer, and I was perched appropriately on the sands of Kogelbaai — one of the most stunning beaches in the Cape. What’s more, it was a weekday afternoon, and so the strand was abandoned but for our small party, so we sat, read, napped, explored the rocks, and enjoyed the beauty of our surrounds. Another cracking read was Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday. The author subtitled his book “A Nightmare” and it had moments of utter fear and dread, but also, being Chesterton, moments of ridiculous farce and hilarity: a fascinating insight into the mind and mentality of a jovial and saintly man.

H.V. Morton, the man who convinced me to come to South Africa with his In Search of South Africa, showed me the Eternal City with A Traveller in Rome, and I am so tantalizingly close to finishing that magnificent work of Thomas Pakenham (now Lord Longford, since the death of his father), The Boer War. Pakenham is an historian beyond compare. I began Kristin Lavransdatter to great enjoyment, but am waiting till my return to New York to complete it. I started The Prisoner of Zenda while travelling in Namibia and finished it on Pentecost weekend. Boswell’s Johnson I found an excellent little india-paper edition of in a tiny back-alley shop in Wells last year (we ran into Michael Alexander on the street) and I’ve been pottering through it bit-by-bit. On the recommendation of Stefan Beck I picked up J.P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man but found it obsessively vulgar and, worse, boring, so returned it to the goodly people at the Universiteit se biblioteek.

I still have out from the library a handsome, handy, small German printing of Legends of the Rhine (translated into English). I like small books, books you can easily fit in the pocket of a field coat and whip out at a moment’s notice. At a reception in a New York gallery some time ago, I learned from John Derbyshire that the determining factor of the old Penguins’ size was that it would fit in the front coat pocket of a British Army officer. The new size of Penguins are much too large to carry about as emergency reading, which makes me very glad that they’ve brought back the older, smaller size.

Penguins aside, I still prefer those shorter, fatter editions printed on thinnest india-paper. Jocelyn, my cook at university, gave me such a copy of The Pickwick Papers (inscribed “To Andrew Cusack — one of the most Pickwickian individuals I have ever met”) for my birthday one year, and it is one of the dearest editions I own. Does anyone print on india-paper anymore? I suspect not, and more’s the pity. Michael Wharton (better known as Peter Simple) noted shortly before his death how difficult it was becoming to obtain sheets of foolscap in London. Thus passes the glories of the world…

Eric Seddon on Washington Irving

Alongside Miklos Banffy, Washington Irving is probably my favourite author. I have two sets of his complete works, and will obtain at least a third — my favourite printing of the complete Irving, in an excellent handy size — when I can find it for the right price. It is curious, but by no means suprising, that Irving’s genius is nearly forgotten today even though he was the first American to be an international superstar, famed on both sides of the Atlantic. He is mostly known only through his authorship of Rip van Winkel and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, both of which works are rarely presented in their original written form, but almost always in shortened illustrated versions for schoolchildren from publishers convinced of their audience’s stupidity.

Irving is rarely in the limelight these days, but First Things Online recently published an informative article, “Washington Irving and the Specter of Cultural Continuity” by one Eric Seddon, that is well worth reading.

His first book, Dietrich Knickerbocker’s History of New York, capitalized on the amnesia of New Yorkers by a mix of biting satire and real history of the Dutch reign in Manhattan. The book is foundational to any study in American humor. It is wild, free, self-deprecatory, and merciless to the public figures of his day, and by turns lyrically funny, absurd, and reflective. Without it, we might wonder whether American humor, from Twain to the Marx brothers to Seinfeld, would have taken the particular shape it did.

When Americans, always prone to utopian daydreams, were in danger of taking themselves far too seriously, when the term “manifest destiny” was embryonic, Dietrich Knickerbocker rolled his bugged-out eyes, chuckled gruffly, and whispered into the ear of a young nation, “Remember thou art mortal.” […]

Irving’s two most famous stories are to be found in The Sketch Book, virtually bookending the text: “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” In “Rip Van Winkle,” Irving whimsically pointed out the hazards of the new Republic, that a once humble acceptance of life under monarchy could easily give way to arrogant corruption, vice, and the nauseating specter of being governed by village idiots with a gift for demagoguery. […]

The final warning of the book comes in the form of a Headless Horseman, who is either a real ghost of the Revolution or the town bully in disguise, and who targets, of all people, the schoolmaster (even small towns have their intelligentsia). Is it history chasing Icabod Crane, the puritanical teacher obsessed with stories of witch hunts, or just Brom Bones scaring him out of town? Irving doesn’t say, and perhaps our answers tell more about ourselves than about him.

Washington Irving spent his last days in Tarrytown, near the setting of his most famous story. He was a member of the local Episcopal Church, tried to revive the old Dutch festivities on St. Nicholas Day, and was moved to tears by singing the Gloria. In particular he loved to repeat the words “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, and good-will to men.” Though his era was in many ways a bigoted one, he resisted and thereby helped to shape a better future. One of his last revisions to Knickerbocker came late, removing the anti-Catholic references its youthful version contained. He was a man who had seen his share of specters, to be sure, but who didn’t believe they were the strongest reality.

Rip van Winkle

POOR RIP van Winkle; I always felt bad for him. He falls asleep for twenty years, and returns to his own native village where is now unknown and taken for some strange vagrant. “I am a poor quiet man, a native of the place, and a loyal subject of the king, God bless him!” he exclaims, in blissful ignorance of the Revolution which took place during his slumber. “A tory! a tory! a spy! a refugee! hustle him! away with him!” cry the by-standers.

I have long thought that Washington Irving was trying to make a subtle traditionalist point here: the definition of a good citizen has been arbitrarily changed. If a man was a good New Yorker in 1765 and hasn’t changed, why is he a traitor in 1785? It’s clearly ridiculous, except to proto-Jacobins and ideologues.

Anyhow, the lesson of the story: drink not from the flagons of odd-looking personages playing nine-pins amidst the Hudson Highlands.

Previously: Rip van Winkle

Rip van Winkle

When was the last time you read the story of Rip van Winkle? If you’ve never had that pleasure, then you are all the worse for it, my friend. The tale was handed down to us through the ages by the munificence of one Diedrich Knickerbocker, though some sore-minded rapscallion later credited the ever-capable Washington Irving with its invention. Anyhow, it is one of my favorite tales in all the history of New York. It’s a short story, and worth a read online if you haven’t a printed copy immediately at hand.

The tale, of course, revolves around “a simple good-natured fellow”, namely Rip van Winkle, and his encounter with “odd-looking personages” whom still to this day show themselves around the Hudson valley. We merely have ceased to hear reports of them because thoroughly unimaginative types are in control of the world these days. (The “monotony monitors” as my Latin teacher monikered them, enforcing boredom and mediocrity at every possible opportunity).

The genealogists amongst you will be interested that Mr. Knickerbocker notes this van Winkle was “a descendant of the Van Winkles who figured so gallantly in the chivalrous days of Peter Stuyvesant, and accompanied him to the siege of Fort Christina.” Now, for want of fast-paced action, you may not have any particular desire to read about a simple, good-natured fellow like Rip van Winkle, but desires aside you must read “the Most Horrible Battle Ever Recorded in Poetry or Prose” (Chapter VII of Book VI of the same Diedrich Knickerbocker’s A history of New York, from the beginning of the world to the end of the Dutch Dynasty). The record of the siege of Swedish Fort Christina by the good New Netherlandish is the most hilarious and enchanting chronicle of any battle anywhere.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories