James II

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Kings, Horse Brands, and Town Seals

The Influence of James II on the Present-Day Municipal Sigillography of Suffolk County, L.I.

THE KEEN STUDENT of town and municipal seals, when perusing the emblems of some of the towns on Long Island, will be intrigued by the curious presence of seemingly inexplicable letters on those of Brookhaven and Huntingdon. Their origin is an intriguing and somewhat surprising one.

The great state of New York takes its name from our late and much-lamented monarch, James II (viz. here and here), who was given the province while still Duke of York during the reign of his brother Charles II. This was a little bit cheeky as the land wasn’t actually Charles’s and was happily occupied by our Dutch forefathers of old, who had every intention of keeping it within the merry garth of their seabound empire.

Nonetheless, a few English ships were sent over and the mercantile population persuaded old peg-legged Peter Stuyvesant not to lose his other leg as they generally thought the prospect of New Amsterdam being shelled and burnt to the ground was not an altogether welcome one and what difference does it make which side of the North Sea one is governed from.

The Province of New York was a proprietary colony of the Duke of York, who promulgated an initial set of regulations known as “the Duke’s Laws” to aid the good administration of the colony. Somewhat eccentrically, rather than proceeding by rank of importance, the Duke’s Laws were arranged alphabetically — e.g. under headings Absence, Actions, Administration, etc.

Under ‘H’ came ‘Horses and Mares’ which provided:

That every Town within this Government, shall have a marking Iron or flesh Brand for themselves in particular to distinguish the Horses of one Town from another, besides which, every Owner is to have, and Mark his Horse or Horses with his owne Particular flesh Brand having some distinguishing mark, that one mans Horses may be known from anothers.

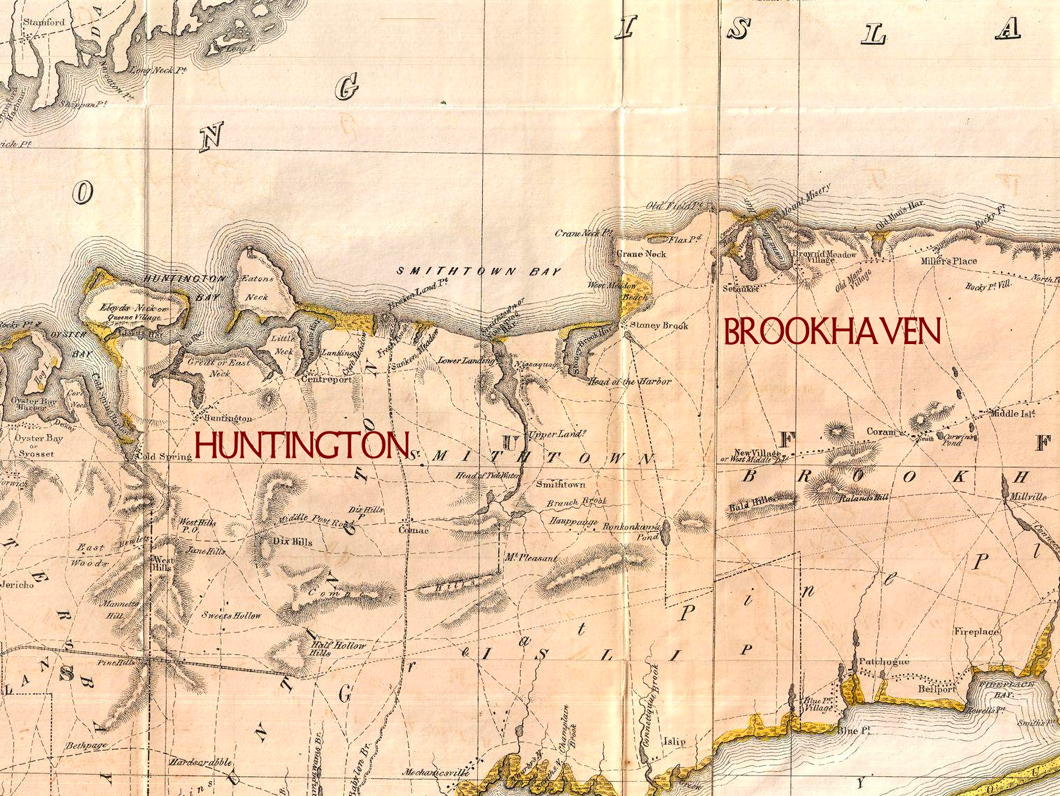

An appendix to the Laws provided that these town horse brands would take letter form, starting on the far end of Long Island with ‘A’ for East Hampton and ‘B’ for Southampton and moving all the way along to ‘Q’ for ‘Utricht’ (New Utrecht) and ‘R’ for Gravesend in Brooklyn on the western end of the island.

Caroline Church, Setauket —

1729, named after Queen Caroline, the wife of George II

‘Seatalcott’, or Setauket as we now call it, was assigned the letter ‘D’. Setauket and Brookhaven were basically interchangeable names for the same place, and Brookhaven eventually won out as the town’s official cognomen.

The town seal was authorised by Governor Thomas Dongan — later the 2nd Earl of Limerick — who in 1686 ordained that “the said trustees of the freeholders and commonality of the Town of Brookhaven do, and may have, and use a common Seale”.

It features the town’s horse brand letter alongside a lance and harpoons signifying the whaling trade which was so prominent in this and many English towns here and further up the Atlantic coast.

Huntington, meanwhile, was assigned the letter ‘E’ for its horse brand and as the fifth town also included five dots alongside the letters HVN representing, (with ‘V’ for ‘U’ in the Latin manner) the town’s name. The rope surrounding the town seal represents the shipping that moved the agricultural products grown in the interior to the shore and on towards their final markets.

The town must have been one in which unsound thinking was rife, as it is believed to be named after the genocidal king-murderer Oliver Cromwell’s home town. Worse, much later the town adopted a coat of arms that was modified from Cromwell’s.

Luckily, wiser counsels have prevailed in more recent times. For the town’s 350th anniversary in 2003 it was decided to stop using the Cromwellian arms and rely solely on the town’s seal.

Huntington’s motto — THE TOWN ENDURES — has an almost cryptic quality. The town church — “Old First” — was founded in 1658 and when its second building was finished in 1715 it acquired a bell from England. Sometime during the Revolution, it was carried away by loyal troops and ended up on HMS Swan, where Huntington native Zebulon Platt noticed it while being held prisoner.

If legend is to be believed, one Nathaniel Williams arranged the return of the bell and had it recast in 1793, including the phrase ‘THE TOWN ENDURES’. This may reflect the 1773 town resolution which provided money for the purchase of a parsonage for the church “to lye forever for that purpose as long as the town endures”.

James II, By the Grace of God

EVERY NOW AND THEN, there is a minor hubbub; perhaps not even enough to be called a hubbub, but call it a hubbub we shall. The hubbub in question is on the subject of James II (seen above, with his father Charles I), our last Catholic king, and the man who (as Duke of York) gave his name to the great city and land of New York. We have previously expounded upon King James on this little corner of the web, but fresh notice was brought by Fr. Nicholas Schofield on his Roman Miscellany blog. In the blog post A Royal Penitent, Fr. Nicholas writes: (more…)

James II, Our Catholic King

THIS PAST SATURDAY was the anniversary of the birth of King James II and VII of England and Scotland. The third son of Charles I, he was baptised into the Anglican church six weeks after his birth and was created Duke of York at eleven years of age. James married Anne Hyde, the daughter of the Earl of Clarendon, by whom he fathered eight children, though only two survived past childhood.

In 1664 the Duke of York equipped an expedition to relieve the Dutch of responsibility for their colonies in North America, and henceforth New Amsterdam and New Netherland were known as New York after their new Lord Proprietor.

Sometime during the year 1670 both the Duke and Duchess of York were received into the Catholic Church and stopped attending Anglican services, though the conversion did not become public knowledge until the Test Act (requiring officeholders to receive communion in a Church of England service and take an oath against Transubstantiation) was passed three years later. James was forced to renounce his offices, such as Lord High Admiral of England, though not his titles. At any rate, Anne, the Duchess of York had died in 1671 only a year after her conversion. He married Princess Maria of Modena in 1673.

The Protestant oligarchs felt threatened by the prospect of a Catholic king and thrice tried to pass laws barring James from succeeding to the throne. However his elder brother Charles II, the reigning king, dissolved parliament each time before the bill was to be passed. King Charles II died in February 1685, (having reconciled himself to the Catholic faith before his end) and thus the Duke of York was proclaimed James II of England and VII of Scotland. A private Catholic coronation was held at Whitehall Palace on April 22 before the public coronation the following day on the feast of Saint George, which was performed according to the rites of the Church of England.

James had appointed the Catholic Thomas Dongan

as Governor of New York in 1682.

The Protestant oligarchs’ fears that James would end their hegemonic grip on Scotland and England proved well-founded as in 1687 he issued a Declaration of Toleration as King of Scotland, allowing Catholics, Episcopalians, and other non-Presbyterians to hold public office and the right of public worship, and a Declaration of Indulgence as King of England removing the laws penalizing non-attendance or non-communion at Church of England services, permitting non-Anglican worship in private homes or chapels, and abolishing religious oaths for public offices. Furthermore, James had allowed Catholics to hold positions at the University of Oxford for the first time since the Protestant Revolution. More provocatively, he tried to transform Magdalen College Oxford into a Catholic seminary. He had already reckoned with the rebellion of the Duke of Monmouth who proclaimed himself king two years earlier but had been captured, tried, and executed for treason. With the birth of a Catholic son and heir, Prince James Francis Edward, in 1688 a cabal of seven Protestant nobles issued an invitation to William of Orange, the Protestant Stadtholder of the Netherlands. A few months later, William of Orange duly arrived and usurped the throne, having already married James’ daughter Mary from his first marriage. The two ruled jointly as William and Mary.

Unwilling to create a popular martyr as had happened with the executed Charles I, William allowed James to escape and fled to France where Louis XIV gave the exiled monarch the use of a palace and an ample pension. James was intent on returning to his birthright, however, and took advantage of the Irish parliament’s refusal to recognise William’s usurpation of the throne. The King landed in Ireland in March of 1689 at the head of a Franco-Irish army but was defeated by William in the famous Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, and returned to his place of exile in France.

There, Louis allowed him to live in the château of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and offered to get James elected King of Poland but James felt this would prevent any chance of a Stuart again holding the throne of England. From that time onwards, James led a simple life of penance in reparation for his sins (he had had a number of mistresses in his younger days) and finally died in 1701. He was entombed in the Chapel of St. Edmund within the English Benedictine church on the Rue St. Jacques in Paris, while his brain was sent to the Scots College in Rome, his heart to the Visitandine Convent at Chaillot, and his bowels divided between the College of St. Omer (the exiled English Catholic school, now Stonyhurst in Lancashire), and the nearby parish church of St. Germain where they remained until they were desecrated by a Revolutionary mob and lost forever. His monument at Saint-Germain, however, was rediscovered in 1824 and is proudly displayed there to this day. There is also a monument to James and the Stuarts in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (c.f. Roma – Caput Mundi).

Aside from the pious tradition that Edward VII was received into the Church on his deathbed, James II was the last Catholic king (and as good King Edward never reigned over New York, James is even more certifiably so for us). There is a lovely coronation ode to James which I just might bring to your attention someday. But for now, reflect and remember our monarchs of old and pray that God in His mercy might grant us good Catholic rulers in stead of the shabby lot we elect today.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Christ Church December 29, 2024

- A Christmas Gift from the Governor December 24, 2024

- Oude Kerk, Amsterdam December 24, 2024

- Gellner’s Prague December 19, 2024

- Monsieur Bayrou December 18, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories