Hungary

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Reclaiming his Birthright

Blessed Emperor Charles’s two homecomings to Hungary after the overthrow of the Hapsburgs are worthy of the greatest spy novels, except they are fact: the hushed secrecy and underground preparations, the airplane contracted under a false name, the disguises used to sneak over borders. In his first attempt, Charles — the Apostolic King of Hungary — made it all the way to Budapest, only to be persuaded to return to exile by the self-appointed regent, Admiral Horthy (a naval commander in what, by then, was a land-locked country).

The King’s second attempt to reclaim his power was much more considered and deliberate, and he spent some time securing a loyal power base of local nobility before pressing on to Budapest by armoured railway train. The King’s force made it to just outside of the Hungarian capital before they were overwhelmed by troops loyal to Horthy — who, in order to maintain their loyalty, neglected to inform the soldiers and officers that the “rebels” they were fighting were actually those of their King and Queen.

Along his path to the capital, the King was greeted by fervent crowds, and stopped at least twice to review small detachments of troops and to show himself in person to his loyal Hungarian subjects. The King had returned, but sadly not for long. After the failure of this second attempt, the Allied powers refused to allow the Imperial & Royal family to remain in mainland Europe, and exiled them to the Portuguese island of Madeira, where the Emperor-King grew ill and eventually died. He is entombed on the island today — a source of great pride, I am told, to the Madeirans.

Elsewhere: Miracle Attributed to Blessed Charles (Norumbega)

The Young Emperor

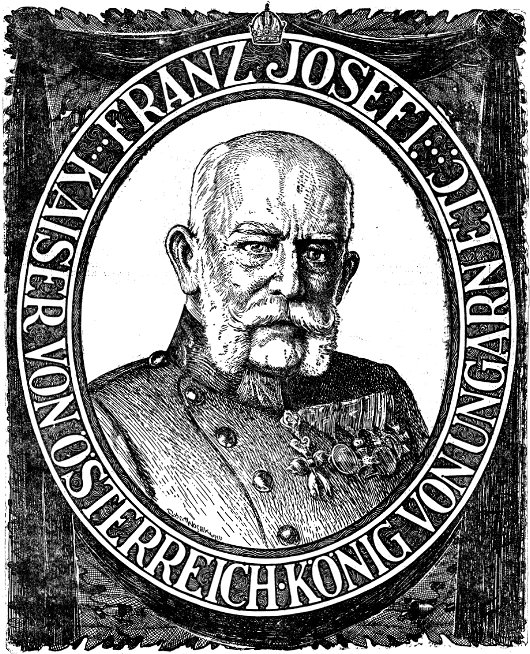

A reader notes in correspondence that Franz Joseph was not always old — though the popular conception certainly is of the Emperor in his later years. Here is the young Franz Joseph (or Ferenc József), just five years after he became Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, Bohemia, &c. The Emperor became so at such a young age because his father, Ferdinand I, abdicated after the revolts of 1848.

This portrait is by the Hungarian painter Miklós Barabás, who also completed portraits of the composer Franz Liszt, the novelist Baron József Eötvös de Vásárosnamény, William Tierney Clark, the Bristol engineer responsible for Budapest’s famous Chain Bridge, and many, many others.

Praying with the Kaisers

by JOHN ZMIRAK

INSIDECATHOLIC.COM

As I’m writing this column at the tail end of my first trip to Vienna, some of you who’ve read me before might expect a bittersweet love note to the Habsburgs — a tear-stained column that splutters about Blessed Karl and “good Kaiser Franz Josef,” calls this a “pilgrimage” like my 2008 trip to the Vatican, and celebrates the dynasty that for centuries, with almost perfect consistency, upheld the material interests and political teachings of the Church, until by 1914 it was the only important government in the world on which the embattled Pope Pius X could rely for solid support. Then I’d rant for a while about how the Empire was purposely targeted by the messianic maniac Woodrow Wilson, whose Social Gospel was the prototype for the poison that drips today from the White House onto the dome of Notre Dame.

And you would be right. That’s exactly what I plan to say — so dyed-in-the-wool Americanists who regard the whole of the Catholic political past as a dark prelude to the blazing sun that was John Courtenay Murray (or John F. Kennedy) might as well close their eyes for the next 1,500 words — as they have to the past 1,500 years.

But as I bang that kettle drum again, I want to set two scenes, one from a fine and underrated movie, the other from my visit. The powerful historical drama “Sunshine” (1999) stars Ralph Fiennes as three successive members of a prosperous Jewish family in Habsburg Budapest. The film was so ambitious as to try portraying the broad sweep of historical change — and, as a result, it was not especially popular. What historical dramas we moderns tend to like are confined to the tale of a single hero, and how he wreaks vengeance on the villains with English accents who outraged the woman he loved. “Sunshine”, on the other hand, tells the vivid story of the degeneration of European civilization in the course of a mere 40 years. The Sonnenschein family are the witnesses, and the victims, as the creaky multinational monarchy ruled by the tolerant, devoutly Catholic Habsburgs gives way through reckless war to a series of political fanaticisms — all of them driven by some version of Collectivism, which the great Austrian Catholic political philosopher Erik von Kuenhelt-Leddihn calls “the ideology of the Herd.”

From a dynasty that claimed its legitimacy as the representative of divine authority at the apex of a great, interconnected pyramid of Being in which the lowliest Croatian fisherman (like my grandpa) had liberties guaranteed by the same Christian God who legitimated the Kaiser’s throne, Central Europe fell prey to one strain after another of groupthink under arms: From the Red Terror imposed by Hungarian Bolsheviks who loved only members of a given social class, to radical Hungarian nationalists who loved only conformist members of their tribe, to Nazi collaborationists who wouldn’t settle for assimilating Jews but wished to kill them, finally to Stalinist stooges who ended up reviving tribal anti-Semitism. The exhaustion at the film’s end is palpable: In the same amount of time that separates us today from President Lyndon Johnson, the peoples of Central Europe went from the kindly Kaiser Franz Josef through Adolf Hitler to Josef Stalin. Call it Progress.

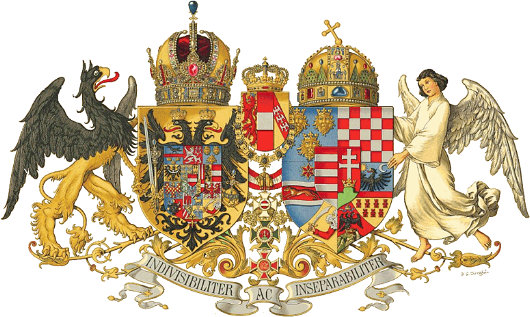

Apart from a heavily bureaucratic empire that spun its wheels preventing its dozens of ethnic minorities from cleansing each other’s villages, what was lost with the fall of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy? For one thing, we lost the last political link Western Christendom had with the heritage of the Holy Roman Empire. (Its crown stands today in the Imperial Treasury at the Hofburg, and for me it’s a civic relic.) Charlemagne’s co-creation with the pope of his day, that Empire had symbolized a number of principles we could do well remembering today: Principally, the Empire (and the other Christian monarchies that once acknowledged its authority) represented the lay counterpart to the papacy, a tangible sign that the State’s authority came not from mere popular opinion, or the whims of tyrants, but an unchangeable order of Being, rooted in divine revelation and natural law.

The job of protecting the liberty of the Church and enforcing (yes, enforcing) that Law fell not to the clergy but to laymen. The clergy were not a political party or a pressure group — but a separate Estate that often as not served as a counterbalance to the authority of the monarchy. No monarch was absolute under this system, but held his rights in tension with the traditional privileges of nobles, clergy, the citizens of free towns, and serfs who were guaranteed the security of their land. Until the Reformation destroyed the Church’s power to resist the whims of kings — who suddenly had the option of pulling their nation out of communion with the pope — no king would have had the power or authority to rule with anything like the monarchical power of a U.S. president. Of course, no medieval monarch wielded 25-40 percent of his subjects’ wealth, or had the power to draft their children for foreign wars. It took the rise of democratic legal theory, as Hans Herman Hoppe has pointed out, to convince people that the State was really just an extension of themselves: a nice way to coax folks into allowing the State ever increasing dominance over their lives.

A Christian monarchy, whatever its flaws, was at least constrained in its abuses of power by certain fundamental principles of natural and canon law; when these were violated, as often they were, the abuse was clear to all, and the monarchy often suffered. In extreme cases, kings could be deposed. Today, by contrast, priests in Germany receive their salaries from the State, collected in taxes from citizens who check the “Catholic” box. So much for the independence of the clergy.

The House of Austria ruled the last regime in Europe that bound itself by such traditional strictures, which took for granted that its family and social policies must pass muster in the Vatican. By contrast, in the racially segregated America of 1914, eugenicists led by Margaret Sanger were already gearing up to impose mandatory sterilization in a dozen U.S. states (as they would succeed in doing by 1930), while Prohibitionist clergymen and Klansmen (they worked together on this) were getting ready to close all the bars. As historian Richard Gamble has written, in 1914 the United States was the most “progressive” and secular government in the world — and by 1918, it was one of the most conservative. We didn’t shift; the spectrum did.

Dismantled by angry nationalists who set up tiny and often intolerant regimes that couldn’t defend themselves, nearly every inch of Franz-Josef’s realm would fall first into the hands of Adolf Hitler, then those of Josef Stalin. Today, these realms are largely (not wholly) secularized, exhausted perhaps by the enervating and brutal history they have suffered, interested largely in the calm and meaningless comfort offered by modern capitalism, rendered safer and even duller by the buffer of socialist insurance. The peoples who once thrilled to the agonies and ecstasies carved into the stone churches here in Vienna can now barely rouse the energy to reproduce themselves. Make war? Making love seems barely worth the tussle or the nappies. Over in America, we’re equally in love with peace and comfort — although we’ve a slightly higher (market-driven?) tolerance for risk, and hence a higher birthrate. For the moment.

Speaking of children brings me to the most haunting image I will take away from Austria. I spent a whole afternoon exploring the most beautiful Catholic church I have ever seen — including those in Rome — the Steinhof, built by Jugendstil architect Otto Wagner and designed by Kolomon Moser. An exquisite balance of modern, almost Art-Deco elements with the classical traditions of church architecture, it seems to me clear evidence that we could have built reverent modern places of worship, ones that don’t simply ape the past. And we still can. A little too modern for Kaiser Franz, the place was funded, the kindly tour guide told me in broken English, by the Viennese bourgeoisie. (Since my family only recently clawed its way into that social class, I felt a little surge of pride.) Apart from the stunning sanctuary, the most impressive element in the church is the series of stained-glass windows depicting the seven Spiritual and the seven Corporal Works of Mercy — each with a saint who embodied a given work. All this was especially moving given the function of the Steinhof, which served and serves as the chapel of Vienna’s mental hospital. (It wasn’t so easy getting a tour!) The church was made exquisite, the guide explained, intentionally to remind the patients that their society hadn’t abandoned them. Moser does more than Sig Freud can to reconcile God’s ways to man.

We see in the chapel the spirit of Franz Josef’s Austria, the pre-modern mythos that grants man a sacred place in a universe where he was created a little lower than the angels — and an emperor stands only in a different spot, with heavier burdens facing a harsher judgment than his subjects. No wonder Franz Josef slept on a narrow cot in an apartment that wouldn’t pass muster on New York’s Park Avenue, rose at 4 a.m. to work, and granted an audience to any subject who requested it. He knew that he faced a Judge who isn’t impressed by crowns.

As we left the church, I asked the guide about a plaque I’d seen but couldn’t quite ken, and her face grew suddenly solemn. “That is the next part of the tour.” She explained to me and the group the purpose of the Spiegelgrund Memorial. It stands in the part of the hospital once reserved for what we’d call “exceptional children,” those with mental or physical handicaps. While Austria was a Christian monarchy, such children were taught to busy themselves with crafts and educated as widely as their handicaps permitted. The soul of each, as Franz Josef would freely have admitted, was equal to the emperor’s. But in 1939, Austria didn’t have an emperor anymore. It dwelt under the democratically elected, hugely popular leader of a regime that justly called itself “socialist.” The ethos that prevailed was a weird mix of romanticism and cold utilitarian calculation, one which shouldn’t be too unfamiliar to us. It worried about the suffering of lebensunwertes Leben, or “life unworthy of life”–a phrase we might as well revive in our democratic country that aborts 90 percent of Down’s Syndrome children diagnosed in utero. So the Spiegelgrund was transformed from a rehabilitation center to one that specialized in experimentation. As the Holocaust memorial site Nizkor documents:

In Nazi Austria, parents were encouraged to leave their disabled children in the care of people like [Spiegelgrund director] Dr. Heinrich Gross. If the youngsters had been born with defects, wet their beds, or were deemed unsociable, the neurobiologist killed them and removed their brains for examination. …

Children were killed because they stuttered, had a harelip, had eyes too far apart. They died by injection or were left outdoors to freeze or were simply starved.

Dr. Gross saved the children’s brains for “research” (not on stem cells, we must hope). All this, a few hundred feet from the windows depicting the Works of Mercy. Of course, they’d been replaced by the works of Modernity.

We’re much more civilized about this sort of thing nowadays, as the guests at Dr. George Tiller’s secular canonization can testify. In true American fashion, our genocide is libertarian and voluntarist, enacted for profit and covered by insurance.

I will think of the children of the Spiegelgrund tomorrow, as I spend the morning in the Kapuzinkirche, where the Habsburg emperors are buried — and the Fraternity of St. Peter say a daily Latin Mass. As I pray the canon my ancestors prayed and venerate the emperors they revered, I will beg the good Lord for some respite from all the Progress we’ve enjoyed.

Blessed Karl I, ora pro nobis.

[Dr. John Zmirak‘s column appears every week at InsideCatholic.com.]

St. Stephen and the Virgin & Child

The Hungarian Bishops’ Conference has a surprisingly handsome logo (above) depicting their patronal saint, King Stephen I, bestowing his crown to the Blessed Virgin and Our Saviour. Some might think the depiction of the Madonna & Child a touch too cartoonish, but I enjoy it.

The Grand Master in Hungary

His Most Eminent Highness, Fra’ Matthew Festing, the Prince & Grand Master of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta made a four-day visit to Hungary last month, from 8-11 of February. The Grand Master was invited to Hungary by the President of the Republic, Mr. László Sólyom, who met with Fra’ Matthew at the Sándor Palace in Budapest. The President and the Grand Master discussed the various collaborative efforts between Hungary and the Order of Malta in health and social fields and discussed the possibility of further developing those projects.

New York Firm Tapped for Restoration of Budapest Landmark

The New York firm of Beyer Blinder Belle, responsible for the restoration of Grand Central Terminal, has been selected to develop “an adaptive reuse and restoration plan” for Exchange Place, a historic building on Budapest’s Freedom Square (Szabadság tér). Exchange Place was built in 1905 for the Budapest Stock and Commodities Exchange, and includes a number of ornamental details in the Hungarian style of the Secession architectural movement. After the Soviet conquest of Hungary, the building became the Lenin Institute before being given over to the state television broadcaster.

God and the Emperor

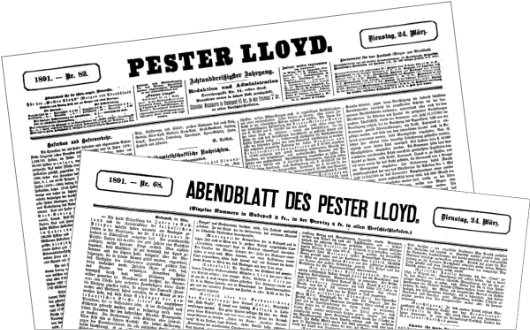

The Pester Lloyd

The Hungarian capital’s German-language newspaper has been “independent, pluralistic, steeped in tradition” since 1854

The fall of the Iron Curtain nearly twenty years ago after a half-century of Communist domination in Eastern Europe afforded an opportunity to revive many of the traditions and institutions which — while they had survived monarchy, republicanism, and fascism — were annihilated by the all-consuming Red totalitarianism. One such institution that has risen from the ashes is Hungary’s once-revered German-language newspaper, the Pester Lloyd.

First appearing in 1854, when Buda and Pest were still two cities flanking the banks of the Danube, the Pester Lloyd was the leading German journal in Hungary. Printed daily with morning and evening editions, the “Pester” in the paper’s name refers to Pest, while “Lloyd” is in imitation of Lloyd’s List (the London shipping & commercial newspaper founded in 1692 by the eponymous properitor of Lloyd’s Coffee Shop and still going strong today). The paper first gained prominence under the editorial leadership of Dr. Miksa (Max) Falk, who had famously tutored the Empress Elisabeth in Hungarian and instilled in the consort a particular love for the Hungarian kingdom.

First appearing in 1854, when Buda and Pest were still two cities flanking the banks of the Danube, the Pester Lloyd was the leading German journal in Hungary. Printed daily with morning and evening editions, the “Pester” in the paper’s name refers to Pest, while “Lloyd” is in imitation of Lloyd’s List (the London shipping & commercial newspaper founded in 1692 by the eponymous properitor of Lloyd’s Coffee Shop and still going strong today). The paper first gained prominence under the editorial leadership of Dr. Miksa (Max) Falk, who had famously tutored the Empress Elisabeth in Hungarian and instilled in the consort a particular love for the Hungarian kingdom.

An Imperial Birthday

Gerald Warner has a splendid post over on his Daily Telegraph blog on Crown Prince Otto’s ninety-sixth birthday. Heavens! how time flies. It seemed like only yesterday was his ninety-fifth.

My favorite scene that Gerald mentions is this one:

Bravo, Budapest. And Hoch Habsburg!

The Coronation of Blessed Charles

Blessed Emperor Charles was crowned as Apostolic King of Hungary on the 30th of December in 1916. It was the last Hapsburg coronation to this day. For those interested there are two accounts which do justice to the sacred rites. One is by that most devoted admirer of the Hapsburgs, Gordon Brook-Shepherd, in his excellent biography of Charles, The Last Hapsburg. (Brook-Shepherd also wrote excellent and quite readable biographies of the Empress Zita, of Crown Prince Otto, of Chancellor Dollfuß, and Baron Sir Rudolf von Slatin Pasha).

Charles & Zita

October 21 was chosen as the Feast of the Blessed Emperor Charles not because it is the date of his death — which is 1 April 1922 — but rather to commemorate the marriage (photo, below) between Archduke Charles of Austria (as he was then) and Princess Zita of Bourbon-Parma in 1911. While Charles died a mere thirty-four years of age, Zita lived on to ninety-six before passing away in 1989 (when I myself was four).

Not very long ago I was in Quebec City, which was where the Empress Zita and the Imperial Family spent their exile during the Second World War. The Hapsburgs, dispossessed first by the Socialists and then by the Nazis, were then so poor they had to collect dandelions from which to make a soup, but they took poverty in their stride. Passing a grassy bit near the Chateau Frontenac, I wondered “Did Crown Prince Otto once pluck weeds from this plot to feed his hungry mother and siblings?”

Also in that ancient Canadian city is La Citadelle, that great hunk of stone and earthworks, perhaps the oldest operational military installation in the New World. There we were lucky enough to be granted access to the tomb of the greatest Canadian, Major General the Rt. Hon. Georges-Philéas Vanier, Governor-General of Canada from 1959 until his death in 1967. General Vanier and his wife had such a reputation for Christian charity and piety that the Vatican is collecting evidence towards their eventual recognition as saints. Their son is Jean Vanier, the founder of the famous l’Arche communities that care for the handicapped and the disabled. I wonder if the Hapsburgs and the Vaniers ever crossed paths in wartime Quebec…

pray for us!

From the memoirs of Miklos Banffy

« After getting home I must admit that I slept soundly, although occasionally, when still half-asleep, I seemed to hear more rumbling of heavy lorries passing under my windows than on previous nights. However, since the street outside was the habitual route for deliveries to the market halls nearby, and the market cars had always rattled past noisily long before dawn, it did not seem to be different from any other night in the year.

It was only later that I heard what had happened early that morning. When my old valet called me he announced three things: my bath had been prepared, revolution had broken out, and Count Mihály Károlyi was now Minister-President. »

NRC, among others, gets it right

The Netherlands’ premier broadsheet has gone partly English online

The moderate liberal Dutch broadsheet NRC Handelsblad is the latest of a series of European periodicals looking for a more international readership by translating part of their content into English for distribution on the world wide web. “NRC International” is partnered with the German weekly magazine Der Spiegel, itself a pioneer in featuring English content in an “international” section of its website. Aside from NRC and Der Spiegel, other news outlets now featuring web-only English-language content are Germany’s Die Welt and Hungary’s Heti Világgazdaság, while Eurozine features translated and original content from a broad spectrum of continental reviews and journals. Sadly, Sign and Sight recently had to reduce their “From the Feuilletons” — looking at the culture pages of German-language newspapers — from a daily to a weekly feature. Sign and Sight also features a weekly “Magazine Roundup” doing the rounds of a wide variety of European, Asian, and American magazines.

The move comes as print newspapers of the conventional variety across Europe and America are losing circulation. Some Manhattan newsstands have seen takers for the Sunday New York Times fall by as much as 80% in the past few years. The New York Times and Wall Street Journal both recently narrowed their page width in a move to save paper costs; the change, however, also means less room for advertising and a more ungainly appearance.

South Africa’s Herald, meanwhile, has bucked the gloomy trend and increased its readership by 14.5% in the past year. The Herald, the Eastern and Southern Cape’s regional broadsheet, attributes its success to a visual redesign and reorienting content to encourage readers to link up with the newspaper’s website. South Africa is also home to The Times (not to be confused with the older Cape Times), a new upmarket broadsheet newspaper launched as a daily extension of the century-old Sunday Times. The weekday Times was started a year ago and its circulation since just June has seen a 10.4% increase.

A major problem for the industry is that formerly high-end newspapers have driven down the quality of their product to a suicidal extent over the past decades. The middle market, for better or worse, is dead, and publishers have three alternatives to this disappearing sector: 1) go lowest-common-denominator — as The Times of London has done, with only moderate success; 2) go up-market — The Times and Sunday Times of South Africa have proved worthwile; or 3) go niche — the New York Observer is still in business after two decades of aiming towards Manhattan’s yuppie community.

Whichever path taken, integrating print and web operations is vital for the survival of print newspapers and other “dead tree” media. That European newspapers are providing at least part of their content in English is helpful in keeping up with events and ideas in countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and Hungary as our native English-language media are tightening their belts and cutting foreign correspondents and coverage. I hope more non-English papers follow this trend and help to permanentize it.

‘The man who walked’

The Daily Telegraph — 6 September 2008

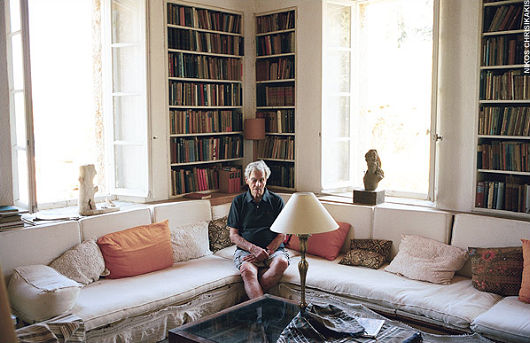

At 18 he left home to walk the length of Europe; at 25, as an SOE agent, he kidnapped the German commander of Crete; now at 93, Patrick Leigh Fermor, arguably the greatest living travel writer, is publishing the nearest he may come to an autobiography – and finally learning to type. William Dalrymple meets him at home in Greece

‘You’ve got to bellow a bit,’ Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor said, inclining his face in my direction, and cupping his ear. ‘He’s become an economist? Well, thank God for that. I thought you said he’d become a Communist.’

He took a swig of retsina and returned to his lemon chicken.

‘I’m deaf,’ he continued. ‘That’s the awful truth. That’s why I’m leaning towards you in this rather eerie fashion. I do have a hearing aid, but when I go swimming I always forget about it until I’m two strokes out, and then it starts singing at me. I get out and suck it, and with luck all is well. But both of them have gone now, and that’s one reason why I am off to London next week. Glasses, too. Running out of those very quickly. Occasionally, the one that is lost is found, but their numbers slowly diminish…’

He trailed off. ‘The amount that can go wrong at this age – you’ve no idea. This year I’ve acquired something called tunnel vision. Very odd, and sometimes quite interesting. When I look at someone I can see four eyes, one of them huge and stuck to the side of the mouth. Everyone starts looking a bit like a Picasso painting.’

He paused and considered for a moment, as if confronted by the condition for the first time. ‘And, to be honest, my memory is not in very good shape either. Anything like a date or a proper name just takes wing, and quite often never comes back. Winston Churchill – couldn’t remember his name last week.

‘Even swimming is a bit of a trial now,’ he continued, ‘thanks to this bloody clock thing they’ve put in me – what d’they call it? A pacemaker. It doesn’t mind the swimming. But it doesn’t like the steps on the way down. Terrific nuisance.’

We were sitting eating supper in the moonlight in the arcaded L-shaped cloister that forms the core of Leigh Fermor’s beautiful house in Mani in southern Greece. Since the death of his beloved wife Joan in 2003, Leigh Fermor, known to everyone as Leigh Fermor, has lived here alone in his own Elysium with only an ever-growing clowder of darting, mewing, paw-licking cats for company. He is cooked for and looked after by his housekeeper, Elpida, the daughter of the inn-keeper who was his original landlord when he came to Mani for the first time in 1962.

It is the most perfect writer’s house imaginable, designed and partially built by Leigh Fermor himself in an old olive grove overlooking a secluded Mediterranean bay. It is easy to see why, despite growing visibly frailer, he would never want to leave. Buttressed by the old retaining walls of the olive terraces, the whitewashed rooms are cool and airy and lined with books; old copies of the Times Literary Supplement and the New York Review of Books lie scattered around on tables between Attic vases, Indian sculptures and bottles of local ouzo.

A study filled with reference books and old photographs lies across a shady courtyard. There are cicadas grinding in the cypresses, and a wonderful view of the peaks of the Taygetus falling down to the blue waters of the Aegean, which are so clear it is said that in some places you can still see the wrecks of Ottoman galleys lying on the seabed far below.

There is a warm smell of wild rosemary and cypress resin in the air; and from below comes the crash of the sea on the pebbles of the foreshore. Yet there is something unmistakably melancholy in the air: a great traveller even partially immobilised is as sad a sight as an artist with failing vision or a composer grown hard of hearing.

I had driven down from Athens that morning, through slopes of olives charred and blackened by last year’s forest fires. I arrived at Kardamyli late in the evening. Although the area is now almost metropolitan in feel compared to what it was when Leigh Fermor moved here in the 1960s (at that time he had to move the honey-coloured Taygetus stone for his house to its site by mule as there was no road) it still feels wonderfully remote and almost untouched by the modern world.

When Leigh Fermor first arrived in Mani in 1962 he was known principally as a dashing commando. At the age of 25, as a young agent of Special Operations Executive (SOE), he had kidnapped the German commander in Crete, General Kreipe, and returned home to a Distinguished Service Order and movie version of his exploits, Ill Met by Moonlight (1957) with Dirk Bogarde playing him as a handsome black-shirted guerrilla.

It was in this house that Leigh Fermor made the startling transformation – unique in his generation – from war hero to literary genius. To meet, Leigh Fermor may still have the speech patterns and formal manners of a British officer of a previous generation; but on the page he is a soaring prose virtuoso with hardly a single living equal.

It was here in the isolation and beauty of Kardamyli that Leigh Fermor developed his sublime prose style, and here that he wrote most of the books that have made him widely regarded as the world’s greatest travel writer, as well as arguably our finest living prose-poet. While his densely literary and cadent prose style is beyond imitation, his books have become sacred texts for several generations of British writers of non-fiction, including Bruce Chatwin, Colin Thubron, Philip Marsden, Nicholas Crane and Rory Stewart, all of whom have been inspired by the persona he created of the bookish wanderer: the footloose scholar in the wilds, scrambling through remote mountains, a knapsack full of books on his shoulder.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

- American Exuberant February 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories