Hungary

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Sombre Land of Shadow and Light

The Budapest of Demeter Balla

Soviet socialism imposed many grim miseries upon the Hungarian people once the German occupation under the National Socialists was replaced by a Russian one under the Red Army. In 1945, Hungarians were allowed one free election in which the Communists were resoundingly defeated.

Two years later, the Russian occupiers allowed another election yet — despite violent intimidation and manufacturing as many as 200,000 false ballots — the Communists still only improved their vote share to 22%. But through various mechanisms it was enough to seize control of the government, take over the other parties, and merge them all into a pro-Soviet front.

A decade later, the 1956 uprising sparked a Soviet invasion to prevent Hungary leaving the Warsaw Pact turning off the road to full communism. It did, however, convince Hungary’s communist hardliners that while total control over all political, social, and economic institutions needed to be maintained, they also needed to lighten the mood. A little more carrot, a little less stick (but keep the stick).

Human beings have a way of sorting themselves out as best they can and persisting despite a multiplicity of hardships. These photographs of Budapest in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s by Hungarian photographer Demeter Balla (1931-2017) bear witness to the quiet dignity of the inhabitants of a capital city still stuck behind the Iron Curtain. (more…)

Ödön von Horváth

When the shop purveying diacritical marks opened one morning in Vienna, in my mind the writer Ödön von Horváth turned up and said “Thanks. I’ll have the lot.”

It wasn’t even his real name, of course — which was Edmund Josef von Horváth. A child of the twentieth century, von Horváth was born in Fiume/Rijeka in 1901. His father was a Hungarian from Slavonia (in today’s Croatia) who entered the imperial diplomatic service of Austria-Hungary and was ennobled, earning his “von”.

“If you ask me what is my native land,” von Horváth said, “I answer: I was born in Fiume, grew up in Belgrade, Budapest, Preßburg, Vienna, and Munich, and I have a Hungarian passport.”

“But homeland? I know it not. I’m a typical Austro-Hungarian mixture: at once Magyar, Croatian, German, and Czech; my name is Hungarian, my mother tongue is German.”

From 1908 his primary education was in Budapest in the Hungarian language, until 1913 when he switched to instruction in German at schools in Preßburg (Bratislava) and Vienna.

Von Horváth went off to Munich for university studies — where he began writing in earnest — but quit midway through and moved to Berlin.

He once told his friends the story of when he was climbing in the Alps and stumbled upon the remains of a man long dead but with his knapsack intact.

Intrigued, he opened the knapsack and found an unsent postcard upon which the deceased had written “Having a wonderful time”.

“What did you do with it?” his friends naturally inquired. “I posted it!” was von Horváth’s reply.

In 1931 he was awarded the Kleist Prize for literature, but two years later the National Socialists took the helm and von Horváth thought it best to move across the border to his old imperial capital of Vienna.

Despite his anti-nationalism, he did initially join the guild for German writers set up by the Nazis, possibly to keep his works in print in the Reich while he was living in still-independent Austria.

It was in Vienna he published his best-known work: Jugend ohne Gott — “Youth without God” (first translated into English as The Age of the Fish), which marked his public point-of-no-return break with the Hitlerites.

The novel depicts a jaded schoolteacher increasingly disconnected from his profession and the world around him as the ideology of National Socialism begins to take root in the education system. (Bizarrely, it was also scantly used as the basis for a 2017 dystopian thriller.)

When Hitler’s troops marched into Austria the following year, von Horváth fled to Paris.

“I am not so afraid of the Nazis,” he told a friend there one day. “There are worse things one can be afraid of, namely things you are afraid of without knowing why. For instance, I am afraid of streets. Roads can be hostile to you, can destroy you. Streets frighten me.”

Days later, in the middle of a thunderstorm, von Horváth was walking down the Champs-Élysées — the most famous street in Paris — when a flash of lightning struck a tree, felled a branch, and struck the writer dead. He had been on his way to the cinema to see Walt Disney’s ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’.

Years ago someone recommended The Eternal Philistine: An Edifying Novel in Three Parts to me, but I have to admit I haven’t yet read it, or much else of von Horváth’s work. (He’s on my fiction wish-list though.)

His plays have been revived, too — here in London at the Almeida and the Southwark Playhouse in the past decade or so — and both The Eternal Philistine and Youth Without God are available in English from the estimable Neversink Library imprint of Melville House.

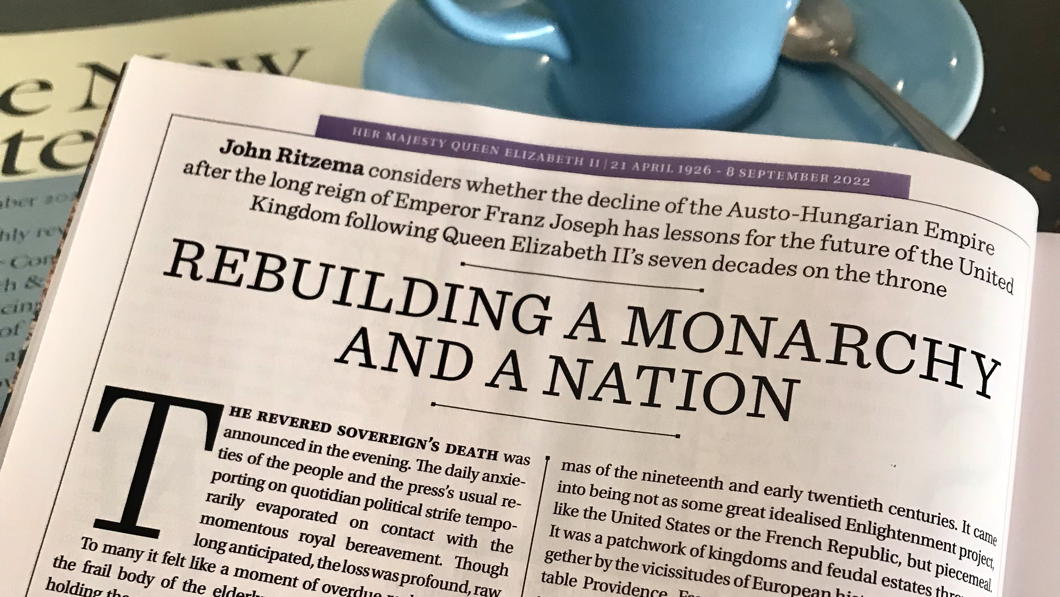

The death of The Monarch

The revered Sovereign’s death was announced in the evening. The daily anxieties of the people and the press’s usual reporting on quotidian political strife temporarily evaporated on contact with the momentous royal bereavement. Though long anticipated, the loss was profound, raw.

To many it felt like a moment of overdue reckoning. As if the frail body of the elderly monarch had somehow been holding the great, ancient, long-weakening and precariously multinational state together. The world of the previous century had finally, almost imperceptibly, slipped away. Franz Joseph was dead. …

In the October 2022 number of The Critic, Dr John Ritzema explores the parallels between the recent demise of our late sovereign with the death of the Emperor Franz Joseph over a hundred years earlier — and wonders whether there are any lessons for the reign of King Charles III: Rebuilding a Monarchy and a Nation.

One of those minor curiosities that both Franz Joseph and Elizabeth II were succeeded by Charleses — the latter by her son, and the former by his grand-nephew Blessed Charles of Austria.

The Saints are Glad

I love this photo of Blessed Charles — here still the heir to the throne — inspecting Austro-Hungarian troops in the Südtirol in 1916.

On the far right of the photograph, Gen. Franz (Ferenc) Rohr von Denta, commander of the Royal Hungarian Army, beams with a massive grin. He looks like a bit of a character.

Next to him is Archduke Eugen, the last Hapsburg to serve as Hoch- und Deutschmeister of the Teutonic Order, which in 1929 was transformed into a priestly religious order.

Franz Joseph would die just months after this photograph was taken.

His grand-nephew and successor Charles would be the last Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary, and King of Bohemia — amongst the myriad other titles — to reign (so far).

From Buda towards Pest

A 1959 view from the Vienna gate of Budapest’s Castle district

Taken in 1959, a photograph in the Fortepan archive shows two girls standing on the stone bench of the Vienna Gate — rebuilt in 1936 to mark the two-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of Buda’s liberation from the Ottomans.

Hungary’s domed neogothic Parliament Building sits in Pest on the opposite bank of the Danube in the distance, with the baroque spire of the Church of the Wounds of St Francis nearer on the Buda side of the river.

Sadly, this fine view can no longer be seen: the trees in the park below the Bastion promenade have been allowed to grow too tall. A somewhat superfluous flagpole bears the banner of Budapest’s 1st District.

The Hungarian government has invested a great deal of care and attention (not to mention investment) to the Castle quarter in recent years, so perhaps restoring this view could be added to their to-do list.

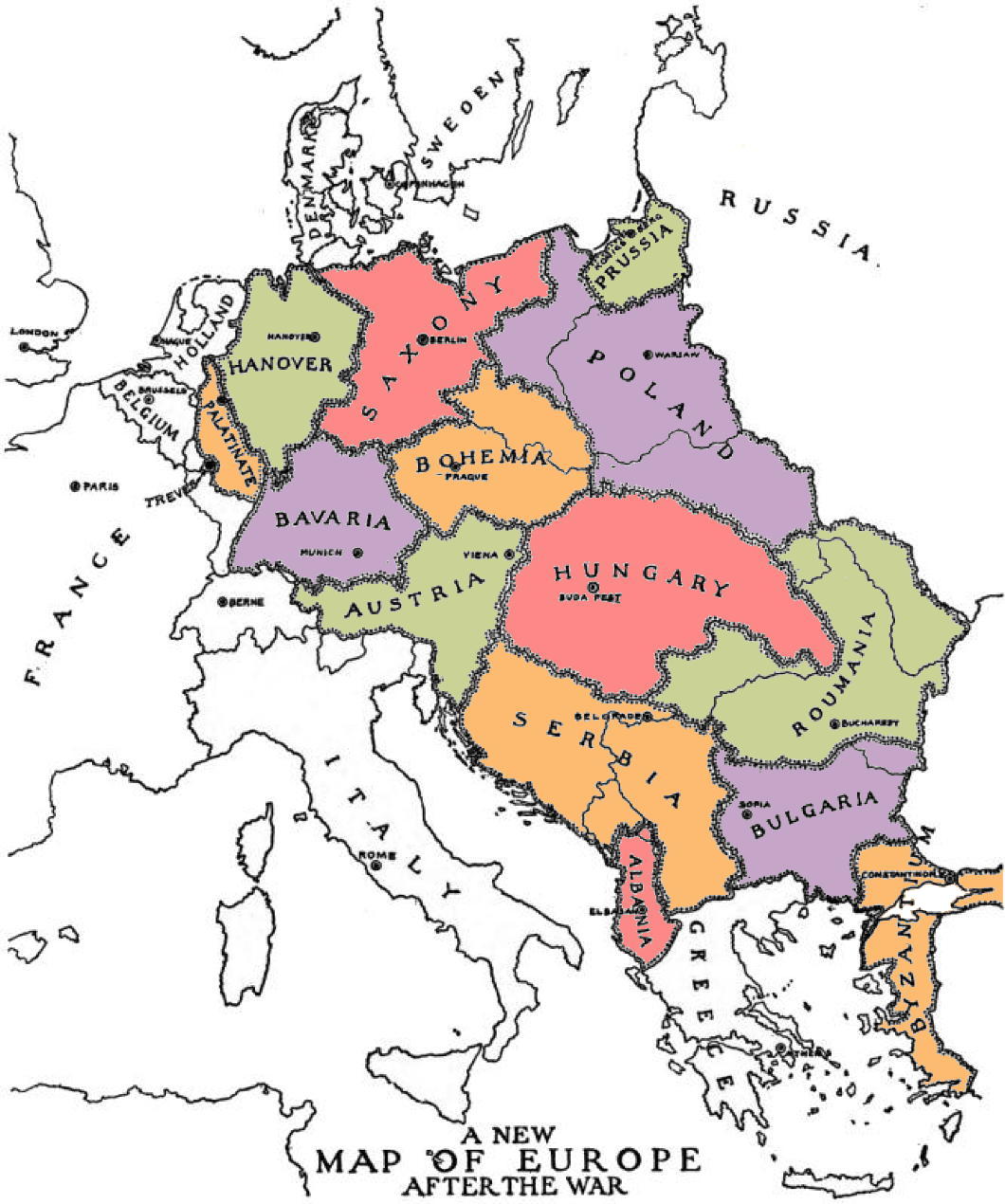

‘Solving’ Middle Europe

Ralph Adams Cram’s First-World-War Plan for Redrawing Borders

Ralph Adams Cram was not just one of the most influential American architects of the first half of the twentieth century: he was a rounded intellectual who expressed his thinking in fiction, essays, and books in addition to the buildings he designed.

Cram (and arguably even more his business partner Goodhue) had a gift for bringing the medieval to life in a way that was neither archaic nor anachronistic but instead conveyed the gothic (and other styles) as living, organic traditions into which it was perfectly legitimate for moderns to dwell, dabble, and imbibe.

His literary efforts include strange works of fiction admired by Lovecraft and political writings inviting America to become a monarchy. These have value, but it’s entirely justifiable that Cram is best known for his architectural contributions.

All the same, amidst the clamours of the First World War this architect of buildings played the architect of peoples and sketched out his idea of what Europe after the war — presuming the defeat of the Central Powers — would look like.

In A Plan for the Settlement of Middle Europe: Partition Without Annexation, Cram set out his model for the territorial redivision of central and eastern Europe “to anticipate an ending consonant with righteousness, and to consider what must be done… forever to prevent this sort of thing happening again”.

Cram, who provided a map as a general guide, predicted the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France, Schleswig-Holstein to Denmark, the Trentino and Trieste to Italy, much of Transylvania to Romania, Posen to a restored Poland, and Silesia divided in three.

Fundamental to the architect’s thinking was that “neither Germany, Austria-Hungary, nor Turkey can be permitted to exist as integral or even potential empires”. Austria and Hungary would be split and Germany needed to be partitioned (not, as some later plans had it, annexed). (more…)

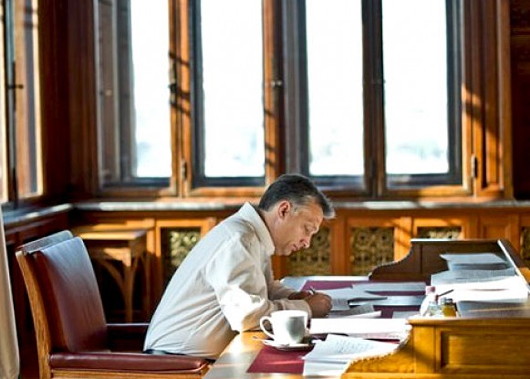

‘The right thing to do is to act virtuously, rather than just talk about doing so’

Welcome to Budapest. Today I do not wish to talk about the persecution of Christians in Europe. The persecution of Christians in Europe operates with sophisticated and refined methods of an intellectual nature. It is undoubtedly unfair, it is discriminatory, sometimes it is even painful; but although it has negative impacts, it is tolerable. It cannot be compared to the brutal physical persecution which our Christian brothers and sisters have to endure in Africa and the Middle East. Today I’d like to say a few words about this form of persecution of Christians. We have gathered here from all over the world in order to find responses to a crisis that for too long has been concealed. We have come from different countries, yet there’s something that links us – the leaders of Christian communities and Christian politicians. We call this the responsibility of the watchman. In the Book of Ezekiel we read that if a watchman sees the enemy approaching and does not sound the alarm, the Lord will hold that watchman accountable for the deaths of those killed as a result of his inaction.

Dear Guests,

A great many times over the course of our history we Hungarians have had to fight to remain Christian and Hungarian. For centuries we fought on our homeland’s southern borders, defending the whole of Christian Europe, while in the twentieth century we were the victims of the communist dictatorship’s persecution of Christians. Here, in this room, there are some people older than me who have experienced first-hand what it means to live as a devout Christian under a despotic regime. For us, therefore, it is today a cruel, absurd joke of fate for us to be once again living our lives as members of a community under siege. For wherever we may live around the world – whether we’re Roman Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox Christians or Copts – we are members of a common body, and of a single, diverse and large community. Our mission is to preserve and protect this community. This responsibility requires us, first of all, to liberate public discourse about the current state of affairs from the shackles of political correctness and human rights incantations which conflate everything with everything else. We are duty-bound to use straightforward language in describing the events that are taking place around us, and to identify the dangers that threaten us. The truth always begins with the statement of facts. Today it is a fact that Christianity is the world’s most persecuted religion. It is a fact that 215 million Christians in 108 countries around the world are suffering some form of persecution. It is a fact that four out of every five people oppressed due to their religion are Christians. It is a fact that in Iraq in 2015 a Christian was killed every five minutes because of their religious belief. It is a fact that we see little coverage of these events in the international press, and it is also a fact that one needs a magnifying glass to find political statements condemning the persecution of Christians. But the world’s attention needs to be drawn to the crimes that have been committed against Christians in recent years. The world should understand that in fact today’s persecutions of Christians foreshadow global processes. The world should understand that the forced expulsion of Christian communities and the tragedies of families and children living in some parts of the Middle East and Africa have a wider significance: in fact they threaten our European values. The world should understand that what is at stake today is nothing less than the future of the European way of life, and of our identity.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We must call the threats we’re facing by their proper names. The greatest danger we face today is the indifferent, apathetic silence of a Europe which denies its Christian roots. However unbelievable it may seem today, the fate of Christians in the Middle East should bring home to Europe that what is happening over there may also happen to us. Europe, however, is forcefully pursuing an immigration policy which results in letting extremists, dangerous extremists, into the territory of the European Union. A group of Europe’s intellectual and political leaders wishes to create a mixed society in Europe which, within just a few generations, will utterly transform the cultural and ethnic composition of our continent – and consequently its Christian identity.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We Hungarians are a Central European people; there aren’t many of us, and we do not have a great many relatives. Our influence, territory, population and army are similarly not significant. We know our place in the ranking of the world’s nations. We are a medium-sized European state, and there are countries much bigger than us which should, as a matter of course, bear a great deal more responsibility than we do. Now, however, we Hungarians are taking a proactive role. There are good reasons for this. I can see – and I know through having met them personally – how many well-intentioned truly Christian politicians there are in Europe. They are not strong enough, however: they work in coalition governments; they are at the mercy of media industries with attitudes very different from theirs; and they have insufficient political strength to act according to their convictions. While Hungary is only a medium-sized European state, it is in a different situation. This is a stable country: the political formation now in office won two-thirds majorities in two consecutive elections; the country has an economic support base which is not enormous, but is stable; and the public’s general attitude is robust. This means that we are in a position to speak up for persecuted Christians. In other words, in such a stable situation, there could be no excuse for Hungarians not taking action and not honouring the obligation rooted in their Christian faith. This is how fate and God have compelled Hungary to take the initiative, regardless of its size. We are proud that for more than a thousand years we have belonged to the great family of Christian peoples. This, too, imposes an obligation on us.

Dear Guests,

For us, Europe is a Christian continent, and this is how we want to keep it. Even though we may not be able to keep all of it Christian, at least we can do so for the segment that God has entrusted to the Hungarian people. Taking this as our starting-point, we have decided to do all we can to help our Christian brothers and sisters outside Europe who are forced to live under persecution. What is interesting about this decision is not the fact that we are seeking to help, but the way we are seeking to help. The solution we settled on has been to take the help we are providing directly to the churches of persecuted Christians. We are not using the channels established earlier, which seek to assist the persecuted as best they can within the framework of international aid. Our view is that the best way to help is to channel resources directly to the churches of persecuted communities. In our view this is how to produce the best results, this is how resources can be used to the full, and this is how there can be a guarantee that such resources are indeed channelled to those who need them. And as we are Christians, we help Christian churches and channel these resources to them. I could also say that we are doing the very opposite of what is customary in Europe today: we declare that trouble should not be brought here, but assistance must be taken to where it is needed.

Dear Friends,

Our approach is that the right thing to do is to act virtuously, rather than just talk about doing so. In this way we avoid doing good things simply in order to burnish our reputation: we avoid doing good things out of calculation, as good deeds must come from the heart, and for the glory of God. Yet now it is my duty to talk about the facts of good deeds. My justification, the reason I am telling you all this, is to prove to us all that politics in Europe is not necessarily helpless in the face of the persecution of Christians. The reason I am talking about some good deeds is that they may serve as an example for others, and may induce others to also perform good deeds. So please consider everything that I say now in this light. In 2016 we set up the Deputy State Secretariat for the Aid of Persecuted Christians, which – in cooperation with churches, non-governmental organisations, the UN, The Hague and the European Parliament – liaises with and provides help for persecuted Christian communities. We listen to local Christian leaders and to what they believe is most important, and then do what we have to. From them I have learnt that the most important thing we can do is provide assistance for them to return home to resettle in their native lands. We Hungarians want Syrian, Iraqi and Nigerian Christians to be able to return as soon as possible to the lands where their ancestors lived for hundreds of years. This is what we call Hungarian solidarity – or, using the words you see behind me: “Hungary helps”. This is why we decided to help rebuild their homes and churches; and thanks to Hungarian Interchurch Aid, in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon we also build community centres. We have launched a special scholarship programme for young people raised in Christian families suffering persecution, and I am pleased to welcome some of those young people here today. I am sure that after their studies in Hungary, when they return to their communities, they will be active, core members of those communities. And we are also working in cooperation with the Pázmány Péter Catholic University on the establishment of a Hungarian-founded university. The Hungarian government has provided aid of 580 million forints for the rebuilding of damaged homes in the Iraqi town of Tesqopa, as a result to which we hope that hundreds of Iraqi Christian families who now live as internal refugees may be able to return to their homes. We likewise support the activities of the Syriac Catholic Church and the Syriac Orthodox Church. I should also mention something which perhaps does not sound particularly special to a foreigner, but, believe me, here in Hungary is unprecedented, and I can’t even remember the last time something like it happened: all parties in the Hungarian National Assembly united to support adoption of a resolution which condemns the persecution of Christians, supports the Government in providing help, condemns the activities of the organisation called Islamic State, and calls upon the International Criminal Court to launch proceedings in response to the persecution, oppression and murder of Christians.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

When we support the return of persecuted Christians to their homelands, the Hungarian people is fulfilling a mission. In addition to what the Esteemed Bishop has outlined, our Fundamental Law constitutionally declares that we Hungarians recognise the role of Christianity in preserving nationhood. And if we recognise this for ourselves, then we also recognise it for other nations; in other words, we want Christian communities returning to Syria, Iraq and Nigeria to become forces for the preservation of their own countries, just as for us Hungarians Christianity is a force for preservation. From here I also urge Europe’s politicians to cast aside politically correct modes of speech and cast aside human rights-induced caution. And I ask them and urge them to do everything within their power for persecuted Christians.

Soli Deo gloria!

Oliver VII

by Antal Szerb, trans. by Len Rix

Pushkin Press (2013), £12, 208 pages

Hungarian by nationality, Catholic by faith, Jewish by blood — Antal Szerb was capable of touching the boundaries of intense seriousness bordering on the mystical (as in Journey by Moonlight) or magical (The Pendragon Legend) even though he is probably better known as paragon and only member of the interwar neo-frivolist school of literature.

Here he is at his frivolous best with a novel about the monarch of a Ruritanian kingdom in crisis who abdicates and escapes to Venice incognito, where he falls in with a crowd of confidence tricksters who ultimately, unaware of the ex-king’s true identity, force him to impersonate himself.

In Oliver VII, romance, intrigue, and the perpetual allure of the genteel portion of the criminal class all combine in an enjoyable farce.

Friday 8 January 2016

– Ross Douthat’s sensitive and thoughtful commentary on the state of the Catholic church (in the New York Times, of all places) has previously sparked apoplexy on the part of liberals, hilariously inspiring a host of bien-pensant establishment lefties to point out he has “no professional qualifications for writing on the subject”.

In a recent blog post, Douthat points out how difficult it is to engage in dialogue with lefty Catholic thinking given that it often assumes we can reinterpret anything whenever we want while ignoring centuries of fervent intellectual inquiry and church teaching. For these liberals, it is always Catholicism: Year Zero.

– The British writer Tibor Fischer is no conservative, but he’s often written how ridiculous it is for people to claim the Viktor Orbán is a dictator, whether in the Guardian or in Standpoint. (I myself had to take to the pages of the Irish Times to defend the Hungarian PM.)

Now Fischer writes in the Telegraph asserting that Viktor Orbán is no fascist: he’s David Cameron’s best chance at reforming the European Union.

– Still in Hungary, the British Embassy in Budapest is moving out of its home of nearly seventy years and into the recently vacated Dutch embassy.

– Everyone loves the leader of the Scottish Conservatives, Alex Massie says. But still no one will vote for her.

– Agnostic Southern Episcopalian chain-smoking monarchist with a penchant for misanthropy: Florence King, RIP.

– Speaking of misanthropy, is Groucho Marx’s humour nihilist? Shon Arieh-Lerer thinks Lee Siegel’s book might be overthinking things a bit.

– And finally, the United Nations Library in New York has announced which of its books was checked out the most often in 2015: Immunity of heads of state and state officials for international crimes.

Letter to the Editor

SIPPING a postprandial Coke last week while flipping through the Irish Times, my wandering eye was drawn towards that newspaper’s report on the Madrid congress of the European People’s Party, the grouping of Christian-democratic and centre-right political parties across the European continent (Madrid congress provides forum for delegates from EU centre-right parties, Suzanne Lynch, Irish Times, 22 October 2015). The correspondent first elucidates some of the purpose of these pan-European gatherings before going on to summarise a number of the issues raised. She ends, however, on a bit of a downer by describing Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s “lurch to the far right”, evidenced by his “clampdown on media and internet freedoms, apparent support for the death penalty and hardline approach to refugees”.

This breezy litany of crimes is little more than shoddy journalism. The alleged “clampdown” refers to proposed internet legislation which has been withdrawn while other media laws requiring balance reflect the U.S. broadcasting rules rescinded under Ronald Reagan. The “apparent support” for capital punishment is another damp squib: Orbán called for it to be debated as intellectual speculation — a canny “dog-whistle” political move to gain votes without requiring any legislative action or serious challenge to the E.U. ban on the death penalty. (It was abolished in Hungary at the fall of communism and there are absolutely positively no government plans to bring it back.)

The refugees allegation was the most interesting, however. As it happened, I had attended a small meeting of British MPs and Hungarian foreign ministry officials the day before Ms Lynch’s report was printed. The Welsh MP David Davies gave his first-hand account of visiting the refugee camps near the Hungarian-Serb border and reported that refugees were being well-looked-after, with the quality of the facilities on the whole at least as good as when he was in the British Army, often better. An advisor from the Hungarian Foreign Ministry briefed us on the general situation, which has calmed down immensely since the Serb border has been more or less closed. He noted that broadcast media across the continent showed footage of Budapest police’s treatment of migrants gathered at the railway station without pointing out that the police were responding to violent attacks from a small minority of migrants.

Proprotionate self-defence for officers of the law is the norm across Europe, but this has mattered little when it comes to depictions of Hungary: the bien-pensant official groupthink is that anything Hungary does is wrong, so long as Fidesz is in power. Luckily some voices of dissent have emerged. The novelist Tibor Fischer — no conservative — described in The Guardian the media treatment of Hungary as “hysterical” and “ignorant nonsense”.

Anyhow, I felt obliged to send off my “Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells” to the Irish Times and it’s very good of their letters staff to print a diverging (if abridged) opinion. The last letter to any editor I succeeded in having printed was in the Times Literary Supplement in 2008 about P.G. Wodehouse’s career in banking at H.S.B.C. Who knows what the next shall bring…

The End of Liberalism

Viktor Orban on the end of the liberal age and the threat to Europe

In a speech to supporters at the Fidesz party’s fourteenth annual Kötcse picnic, the Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán has claimed that the refugee crisis is a portent of the end of “the era of liberal babble”. The current “identity crisis” of liberalism, Orbán argued, presented both “huge risk” and “a new opportunity” to return to Christian and communal identities.

Mr Orbán said that the dominant liberal ideology had weakened Europe while preserving its wealth. “The most dangerous combination known in history is to be both rich and weak,” he argued. “It is only a matter of time before someone comes along, notices your weakness, and takes what you have.”

“The liberal philosophy is a result of a Europe which is weak and which also wants to protect its wealth; but if Europe is weak, it cannot protect this wealth.”

Mr Orbán also attacked the liberal imperialism of military intervention, asserting it has been based on fundamental hypocrisy and simplistic Manichean thinking: (more…)

L’Osservatore Romano goes Hungarian

Magyarophiles will be pleased to learn that L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper, will begin appearing in Hungarian. The new edition will appear every other week as a four-page insert into Új Ember, the Hungarian Catholic weekly founded in 1945. “We are a small editorial staff,” Balázs Rátkai, editor-in-chief of the weekly, told L’Osservatore.

“However, our intention is to probe and to make our readers think. The collaboration with the Vatican daily is of historic importance for the life of the weekly and of the entire local Church; it not only brings the Universal Church and the Pope closer to us; it will also enrich readers, and through them all of Hungarian society, with new thoughts, opinions and answers.”

Printed as a daily broadsheet in Italian, the Vatican newspaper also has weekly tabloid editions in French, Spanish, English, German, and Portuguese, as well as a monthly version in Polish.

Squabbles Over Szekler Flag

In Transylvania, a “flag war” has broken out between Romanian politicians and the representatives of the Hungarian-speaking Szekler people. As România Libera reports, no one is offended by flying the old Hapsburg flag over the fortress of Alba Iulia (De: Karlsburg, Hu: Gyulafehérvár), the Romanian government takes umbrage at the appearance of the blue-and-gold flag of the Szekler (or Székely) people who live primarily in three of Transylvania’s counties. (more…)

Hungary Reasserts Sovereignty

Deputy PM Navracsics asserts to shocked Commissioner that Council of Europe “cannot impose anything which runs counter to our constitution”

Hungary yesterday declared its sovereign primacy over the EU. In a heated dialogue between Tibor Navracsics and Commissioner Neelie Kroes, the Hungarian deputy PM staidly remarked that his country would not impose legislation which was contrary to its new constitution. The packed committee room gasped in horrified awe. Kroes was visibly furious as she stormed out, expressing her usual ‘grave concerns’ about Hungary.

Kroes had obviously been banking on Navracsics’s compliance with the Council of Europe’s recommendations, EU member states being bound to comply with the Council of Europe’s Fundamental Charter of Human Rights under the Treaty of Lisbon. The Hungarian government is under scrutiny from the EU for the possible breach of various articles of the Charter. When asked directly where his priorities lay in implementing recommendations, however, the founding member of the ruling Fidesz party stated “I’m a Hungarian member of parliament and I have sworn allegiance to the constitution of Hungary.” (more…)

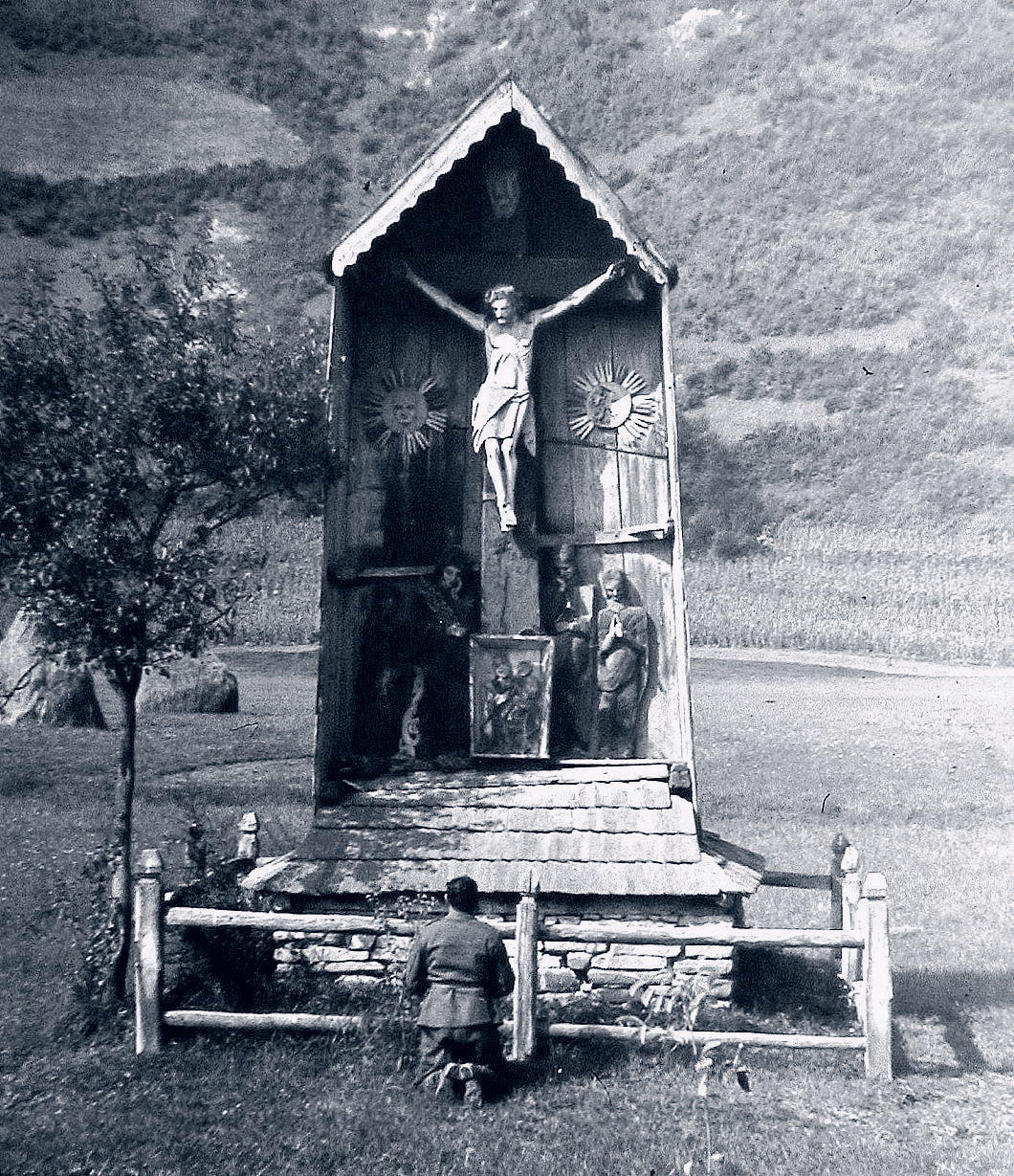

Charles of Austria

TODAY IS THE first feast of Blessed Charles since the announcement last December that the cause for the canonisation of his wife, Zita of Bourbon-Parma, has been opened as well. In an age when most people in government and public leadership seem barely even decent, let alone saints, it is all the more important to seek the prayers and intercession of Charles and Zita — husband and wife, mother and father, Emperor and Empress — for the preservation of peace, the prevention of war, and the renovation of our families as well as our societies at large. (more…)

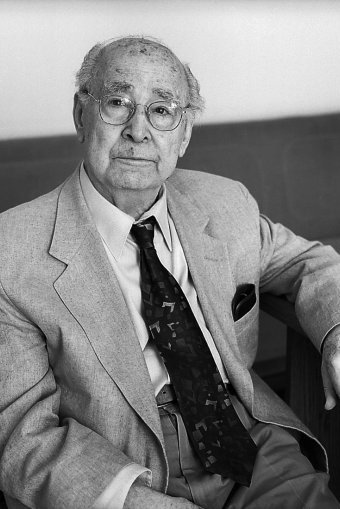

Thomas Molnar, 1921–2010

The Catholic philosopher and historian Thomas Molnar died last week in Virginia at eighty-nine years of age, just six days short of reaching his ninetieth year. Born Molnár Tamás in Budapest in 1921, the only son of Sandor and Aranka, Molnar was schooled across the Romanian border in the town of Nagyvárad (Rom.: Oradea) in the Körösvidék, a region often included in Transylvania and an integral part of Hungary until the Treaty of Trianon cleaved it a year before. In 1940 he moved to Belgium to begin his higher education in French, and as a leader in the Catholic student movement he was interned by the German occupiers and sent to Dachau. With the end of hostilities, he returned to Brussels before arriving home in Budapest to witness the gradual Communist takeover of Hungary.

and historian Thomas Molnar died last week in Virginia at eighty-nine years of age, just six days short of reaching his ninetieth year. Born Molnár Tamás in Budapest in 1921, the only son of Sandor and Aranka, Molnar was schooled across the Romanian border in the town of Nagyvárad (Rom.: Oradea) in the Körösvidék, a region often included in Transylvania and an integral part of Hungary until the Treaty of Trianon cleaved it a year before. In 1940 he moved to Belgium to begin his higher education in French, and as a leader in the Catholic student movement he was interned by the German occupiers and sent to Dachau. With the end of hostilities, he returned to Brussels before arriving home in Budapest to witness the gradual Communist takeover of Hungary.

Molnar left for the United States, where he earned his Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1950. He frequently contributed to the pages of National Review after its foundation by William F. Buckley in 1955, and his periodic writings were often found in Monde et Vie, Commonweal, Modern Age, Triumph, and other journals. From 1957 to 1967 he taught French & World Literature at Brooklyn College before moving on to become Professor of European Intellectual History at Long Island University. In 1969 he was a visiting professor at Potchefstroom University in the Transvaal. In 1983 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Mendoza in Argentina while he was a guest professor at Yale. After the fall of the Communist regime in Hungary, he taught at the University of Budapest and at the Catholic University (PPKE). In 1995 he was elevated to the Hungarian Academy of Arts.

While his first book, Bernanos: his political thought and prophecy (1960), was well-received, it was Molnar’s second published work that was arguably his best known. The Decline of the Intellectual (1961) was, in Molnar’s own words, “greeted favorably by conservatives, with respectful puzzlement by the left, and was dismissed by the liberal progressives.” Gallimard began discussions to print a French translation as part of its prominent Idées series, before the publisher’s in-house Marxist Dionys Mascolo vetoed it for its treatment of Marxism as a utopian ideology. The celebrated & notorious Soviet spy Alger Hiss complimented it in a Village Voice review, but Molnar noted that The Decline of the Intellectual‘s harshest criticism came from liberal Catholic circles. “Obviously,” he wrote, “in that moment’s intellectual climate, they would have preferred a breathless outpouring of Teilhardian enthusiasm.”

The book argued, from a deeply conservative European mindset, that the rise of the intelligentsia during the nineteenth century was tied to its capacity as an agent of bourgeois social change. As the intellectual class increasingly shaped the more democratic, more egalitarian (indeed, more bourgeois) world around it, the intelligentsia’s vitality, so tied to its capability to enact social change (Molnar argued), became self-destructive. The “decline” set in as the intelligentsia searched for alternative methods of social redemption in increasingly extreme fashions (such as nationalism, socialism, communism, fascism, &c.) and led to the intellectuals allying themselves with ideology, which is the surest killer of genuine intellectual and philosophical speculation.

The same year Molnar’s The Future of Education was published with a foreword by Russell Kirk, whose study of American conservative thinkers, The Conservative Mind, was admired by Molnar. Among the many works that followed were Utopia, the perennial heresy (1967), The Counter-Revolution (1969), Nationalism in the Space Age (1971), L’éclipse du sacré : discours et réponses in 1986 with Alain Benoist, and the following year The Pagan Temptation refuting Benoist’s neo-paganism, The Church, Pilgrim of Centuries (1990), and in 1996 Archetypes of Thought and Return to Philosophy. From then until his death, the remainder of his new books have been published in his native Hungarian language.

Molnar and his work have become sadly neglected for the very reasons he detailed in his major work: the overwhelming triumph of ideology over the intellectual sphere. While Russell Kirk defined conservatism as the absence of ideology, modern conservatism in America has become almost completely enveloped by ideology, and the Molnar’s deep, traditional way of thinking — influenced to a certain extent by de Maistre and Maurras — is now met more by silence and ignorance than by direct condemnation.

The triumph of ideology (be it on the left or the right) was aided and abetted, Molnar argued, by a culture dominated by media and telecommunications. “Around 1960,” Professor Molnar wrote later in his life, “the power of the media was not yet what it is today.”

Hardly anybody suspected then that the media would soon become more than a new Ceasar, indeed a demiurge creating its own world, the events therein, the prefabricated comments, countercomments—and silence. … The more I saw of universities and campuses, publishers and journals, newspapers and television, the creation of public opinion, of policies and their outcome, the less I believed in the existence of the freedom of expression where this really mattered for the intellectual/professional establishment. For the time being, I saw more of it in Europe, anyway, than in America: over there, institutions still stood guard over certain freedoms and the conflict of ideas was genuine; over here the democratic consensus swept aside those who objected, and banalized their arguments. The difference became minimal in the course of decades.

Needless to say, the world of American conservatism has been silent in responding to the death of Professor Molnar.

Ideology’s enforced forgetfulness aside, Molnar’s native Hungary renewed its appreciation for him just before his death: last year the Sapientia theological college organised the first conference devoted to his works, which was well-attended and much commented-upon in the Hungarian press. Besides his serious corpus of works, Molnar is survived by his wife Ildiko, his son Eric, his stepson Dr. John Nestler, and his seven grandchildren.

Requiescat in pace.

Previously: Understanding the Revolution

Elsewhere: Professor Thomas Molnar, In Memoriam

Films Recently Watched

In reverse chronological order, from the most recently viewed backwards.

|

Ne touchez pas la hache (2007, France) — Based on Balzac’s La Duchesse de Langeais. I think we need more films set in Restoration France, but this one often fell flat. |

|

Män som hatar kvinnor (2009, Sweden) — A journalist has six months to investigate the strange murder of a girl from the island estate of a prominent family. A very good mystery, though I had to fast-forward multiple times due to graphicness. Released in the U.S. as ‘The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo’ instead of ‘Men Who Hate Women’. |

|

The Night of the Generals (1967, Great Britain-France) — A quality production depicting the quest of a German officer to obtain justice in arresting a sociopathic general for the murder of a Polish prostitute. Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole, Philippe Noiret, Christopher Plummer, Charles Gray, and Tom Courtenay. |

|

Three Days of the Condor (1975, U.S.A.) — A literary analyst at a CIA front organisation returns to the office from lunch to find all his colleagues shot dead. Robert Redford and Max von Sydow. |

|

Le combat dans l’île (1962, France) — A right-wing extremist thinks he’s assassinated a prominent left-wing extremist but soon finds not all is as it appears. Romy Schneider plays the woman caught between the would-be murderer and his typographer friend. |

|

À bout de souffle (1960, France) — A rather lame romanticisation of a cop-murderer and his exploits from Jean-Luc Godard. Paris in the 1950s looks great though. |

|

Defence of the Realm (1985, Great Britain) — A newspaper exposes a Member of Parliament as a potential spy, but it turns out the story is much more complicated than first appearances would have it. Starring Gabriel Byrne, Ian Bannen, Greta Scacchi, Denholm Elliott, Bill Paterson, and Robbie Coltrane. |

|

A Few Days in September (2006, France) — An intriguing spy drama set in the days leading up to September 11th, a French spy (Juliette Binoche) is minding the grown children of an old ex-C.I.A. agent (Nick Nolte) pursued by a psychotic assasin (John Torturro). |

|

50 Dead Men Walking (2008, Great Britain-U.S.A.-Canada) — Based on the story of terrorist-turned-informer Martin McGartland, with Ben Kingsley playing his RUC handler. |

|

The Red Baron (2008, Germany) — A very light handling of an interesting historical character man. Everyone dresses well, but Joseph Fiennes as Billy Bishop, the Red Baron’s nemesis, is the least convincing fighter ace in history. |

|

Ondskan (2003, Sweden) — A surprisingly good film in the boarding-school resistance-to-bullies category with a few twists, only slightly tinged by the socialism of the author of the novel on which it’s based. |

|

L’Heure d’été (2008, France) — Three siblings deal with their mother’s estate. |

|

Sink the Bismarck! (1960, Great Britain) — Cracking naval tale. A classic of the World War II genre. |

|

The Count of Monte Cristo (2002, U.S.A.) — Significant changes from the plot of the book besides the usual compression of the story line mar this film. Just not as worthwhile as the lavishly done 1998 French mini-series. |

|

On the Waterfront (1954, U.S.A.) — A priest tries to convince a mob lackey to testify against his bosses to challenge their murderous and abusive control of the waterfront. Particularly intriguing as the director was brave enough to challenge Hollywood communists in the 1950s. |

|

Paris (2008, France) — The interweaving lives of a handful of Parisians. I will see any film that has Juliette Binoche or Mélanie Laurent in it, and this film has both. Also with François Cluzet (of “Ne le dis à personne/Tell No One”) and Albert Dupontel. |

|

Mon Oncle (1958, France) — Jacques Tati’s first colour film, Monsieur Hulot continues to struggle with the postwar infatuation with modern architecture and consumerism. On its release it was condemned for its obviously reactionary world-view, but has since become a cult favourite. |

|

Le Petit Lieutenant (2005, France) — A young police recruit from the provinces joins a Parisian precinct and investigates a murder alongside his female unit commander, a recovering alcoholic. |

|

Les rivières pourpres (2000, France) — Jean Reno plays a police detective sent to a small university town in the Alps to investigate a brutal murder. Meanwhile, another detective (played by Vincent Kassel) looks into the desecration of the grave of a young girl. The plots soon become intertwined in an intriguing fashion. This film failed to live up to its potential (the university aspect could have been developed further) but is still a decent cop flick. |

|

Buongiorno, notte (2003, Italy) — The kidnapping of Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades. |

|

Flammen & Citronen (2008, Denmark) — Another good Scandinavian World-War-II resistance movie, alongside Norway’s “Max Manus” of the same year. (Previously covered here). Mads Mikkelsen (the Bond villain in “Casino Royale”) plays ‘Citronen’. |

|

Kontroll (2003, Hungary) — The ticket collectors of the Budapest Metro worry about a series of mysterious platform deaths. Varies between the comic, the thrilling, and the tiresome. |

|

L’homme du train (2002, France) — A man steps off a train planning to rob a bank, but strikes up a friendship with a retired poetry teacher. Jean Rochefort and Johnny Hallyday are a surprisingly good pairing. |

|

Advise and Consent (1962, U.S.A.) — The Senate must either approve or reject the President’s nomination for Secretary of State, but plots and intrigues are afoot. Otto Preminger does Washington, and does it well. |

|

The International (2009, U.S.A.-Germany-Great Britain) — A cracking conspiracy thriller staring Clive Owen as a stubborn Interpol investigator and Naomi Watts as a Manhattan Assistant D.A. Includes a fun shoot-out in the Guggenheim. |

|

Banlieue 13 (2004, France) — Parkour-heavy action film set in a Parisian crime ghetto of the near-future. |

|

Il divo (2008, Italy) — Biographical film of the seven-time Italian prime minister Giulio Andreotti. Toni Servillo’s portrayal of the main character, however, crosses the line into caricature. |

|

Strajk – Die Heldin von Danzig (2006, Germany-Poland) — A German film in Polish about the hardest-working employee at the Gdansk shipyards who finally takes a stand against the horrendous working conditions under the Communist regime. |

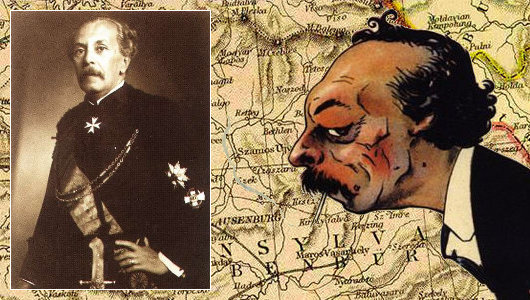

‘The Tolstoy of Transylvania’

In his column in the Daily Telegraph, former editor Charles Moore praises Miklos Banffy as ‘the Tolstoy of Transylvania’. Ardent Banffyites like myself are always pleased when the Hungarian novelist gets attention in the English-speaking world, which happens all too rarely. I can’t remember how on earth I stumbled upon the works of Banffy, probably through reading the Hungarian Quarterly, a publication that — covering art, literature, history, politics, science, and more — is admirably polymathic in our age in which the specialist niche is worshipped.

To put it simply, Banffy is a must-read. If you love Paddy Leigh Fermor’s telling of his youthful walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople (the third and final installation of which we still await), then Miklos Banffy will be right up your alley. Start with his Transylvanian trilogy — They Were Counted, They Were Found Wanting, and They Were Divided.

The story follows two cousins, the earnest Balint Abady and the dissolute László Gyeroffy, Hungarian aristocrats in Transylvania, and the varying paths they take in the final years of European civilization. The novels “are full of love for the way of life destroyed by the First World War,” Charles Moore points out, “but without illusion about its deficiencies.”

Three volumes of nearly one-and-a-half thousand pages put together, they make for deeply, deeply rewarding reading, transporting you to the world that ended with the crack of an assassin’s bullet in Sarajevo, 1914.

After finishing his trilogy, Banffy’s autobiographical The Phoenix Land is worthwhile; some of the real events depicted shadow those in the fictional novels. As previously mentioned, it contains a description of the last Hapsburg coronation (that of Blessed Charles) and numerous amusing tales.

After that, I’m afraid you will have to learn Hungarian, which I have neglected to do, as no more of this author’s oeuvre has yet been translated into English.

The Messiah in the Sportpalast

The following feuilleton was written before Hitler became the master of Germany. The scene is the Berlin Sportpalast, the largest indoor arena in the world when it opened in 1910 and, at this time, the setting for the rallies of the various political parties vying for control of the Weimar Republic.

On the night of the Horst Wessel commemoration Hitler speaks in the Berlin Sportpalast. People who have neither seen nor heard him will perhaps never fully understand the significance of the profoundly ominous mind-set that has developed in Germany since the war. The reality — Hitler’s version of reality and its full implications — goes far beyond anything you might read in the newspapers, or imagine. Here is that reality, drawn from the life. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

- American Exuberant February 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories