History

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Borris House

The County Carlow seat of the MacMorrough Kavanaghs, ancient Kings of Leinster, whose sixteenth generation live here still.

In Old Rio

The city’s administrative and electoral units were its parishes, and the tallest buildings were all church towers. The day of the colonial port began with the cannon shot announcing the beginning of harbour commerce, at half past five.

This was followed by the opening of shops and homes of merchants and tradesmen. Early mass was signalled by church bells, and it was church bells which marked the day’s turn as they sounded the day’s regular prayers as the sun rose and set. …

One of the first, common sights in the city was that of Catholic brotherhoods seeking alms in the streets and shops, or, perhaps, a lady, humbly barefoot, seeking to fulfil a vow by begging alms with a heavy silver tray covered with rich cloth — accompanied by her servant, of course.

The Conservatives, the State, and Slavery in the Brazilian Monarchy, 1831-1871

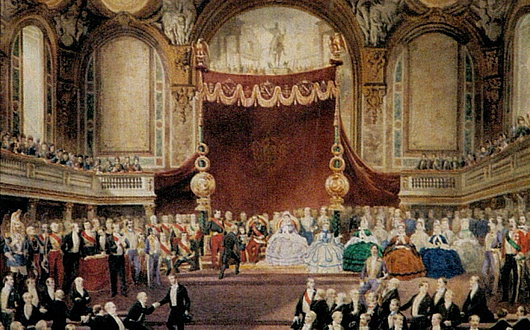

Evolution of a Napoleonic Parliament

The Salle des états in the Palais du Louvre

Among the numerous rituals of the ordinary visitor’s pilgrimage to Paris — trip up the Eiffel Tower, lunch at a tourist-trap café — braving the teeming hordes in the Louvre to view da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ ranks near the top. What very few of the camera-toting hordes realise is that they are shuffling through the room that once housed France’s parliament. The history of the Palais du Louvre is long, exceptional, and varied.

Originally built as a stern castle in the 1190s, the Louvre’s secure reputation led Louis IX to house the royal treasury there from the mid-thirteenth century. Charles V enlarged it in the fifteenth century to become a royal residence, while François Ier brought the grandeur of the Renaissance to the Louvre — as well as acquiring ‘La Gioconda’. In 1793, amidst the revolutionary tumult, part of the palace was opened to the public as the Musée du Louvre, but the Louvre has always housed a variety of institutions — the Ministry of Finance didn’t move out until 1983.

Napoleon III took as his official residence the Tuileries Palace which the Louvre was slowly enlarged towards over the centuries to incorporate. The Emperor needed a parliament chamber close at hand so he could easily address joint sittings of the Senate and the Corps législatif (as the lower house was called during the Second Empire) which opened the parliamentary year. By doing so at his residence, the Bonaparte emperor was following the example left by his kingly Bourbon predecessor Louis XVIII. (more…)

Les jours heureux du Liban

Being an omnivore of nations I’m not short of favourite countries, but the Lebanon is towards the top of my list. I’ve spent some weeks there each summer for the past few years and we’re hoping to return this July (God willing). Friday night B. invited a few of us round for an impromptu supper and in the kitchen I happened to mention that I had met his ambassador the day before — the Lebanese ambassador.

This provoked a lament on B’s part as he relayed the history of his family’s service in the diplomatic corps and of Lebanon in the old days: black-tie dinners, summer in the mountains, the casinos and the glamour of the Beirut he was born too late to experience.

It’s become a cliché for foreigners to cite Beirut’s former glory as ‘the Paris of the Orient’ and Lebanon ‘the Switzerland of the Middle East’. Civil war wreaked its devastation on the country but its revival in more recent years has still been remarkable. Everything, of course, is exceptionally tenuous, but despite the clouds of uncertainty there remains a lot for which to be grateful.

We both wished, however, that today’s ordinary culture in Lebanon was a bit more informed by the style of the past. While old buildings are often restored, far too many of the new buildings are horrendously bland or offensively modern. Perhaps most unfortunately, a large proportion of Lebanon’s women — already endowed with a natural beauty unparalleled in the Middle East — are too mimicking of American styles: nosejobs and dyed blonde hair.

For my part, however, the conversation provoked a little dip into the photographic archives, seeking out some images of Lebanon in its halcyon days. (more…)

Kolmanskop

Ghost town of the Namib

NAMIBIA IS A LAND that fascinates me, which is perhaps surprising. This arid land is sparsely populated — just 6.6 people per square mile — but its deserts are believed to be the oldest in the world. Those who haven’t experienced its harsh beauty may wonder why this land has attracted its odd and varied collection of peoples, but here the Ovambo, the Kavango, the Herero, the Afrikaner, the German, and the Bushman all call home.

I have already written somewhat about Lüderitz and beyond it the Diaz Point. As you speed down the B4 from Keetmanshoop to Lüderitz — a four-hour drive passing through just the one small village of Aus — you can turn off just before you reach the coastal town and pay a visit to the eerily ghost town of Kolmanskop: Kolmannskuppe in the original German. (more…)

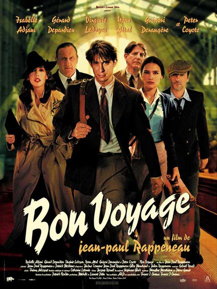

‘Bon Voyage’

Jean-Paul Rappeneau’s ‘Bon Voyage’ (2003) is one of those superb films that come around all too rarely. It manages to balance perfectly all the elements of drama, comedy, action, and romance, set in a convincing historical context.

Bon Voyage

Jean-Paul Rappeneau

2003, France

1 hour 54 minutes

In 1940, Viviane Denvert (played by Isabelle Adjani) is a fickle, self-promoting film star who enlists her childhood friend, Frédéric Auger (Grégori Derangère), to extract herself from a compromising situation. As war creeps upon France, Auger finds himself behind bars for Viviane’s crime, but in the confusion of battle he manages to escape with the seasoned ne’erdowell Raoul (Yvan Attal). All of Paris is fleeing the German advance, and on the train to Bordeaux the two come across physics student Camille (Virginie Ledoyen) who helps them reach the western city by car when the train is stopped on the line.

In Bordeaux we come across government minister Jean-Étienne Beaufort, Viviane’s lover whom she uses to get Frédéric out of a sticky situation resulting from her own manipulation of him. Meanwhile, with all of Paris in Bordeaux, Viviane comes across another ex-paramour, Alex Winckler (Peter Coyote), keeping an unnatural interest in the affairs of the government, while the physics student Camille and her mentor Professor Kopolski are harbouring an important cargo they are determined must not fall into the hands of the Germans.

For fear of spoilers, that is all I will say about the plot, but it all comes packaged in a score by Gabriel Yared, better known for his scoring of ‘The English Patient’, ‘The Talented Mr. Ripley’, and Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s ‘Das Leben der Anderen’. The film was nominated for eight César awards in 2004 — best costumes, best director, best editing, best film, best original score, best sound editing, best supporting actor, and best writing — while it won three Césars that year for photography, best set design, and, for Grégori Derangère, best promising actor. (more…)

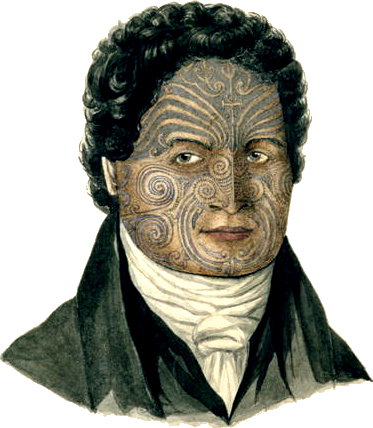

A Maori in Buenos Aires

The Argentine stopover of Te Pēhi Kupe

So  far as I can tell, the first Maori to visit Argentina (or the United Provinces of the River Plate as it was then called) was the young nobleman Te Pehi Kupe in October 1824. (The name is spelt varyingly as Te Pēhi Kupe, Tupai Cupa, Te Pai Kupa, and Tippahée Cupa). Te Pehi was born on the North Island, probably around 1795, and was a senior-line descendant of Toarangatira (founder of the Ngati Toa tribe) as well as an uncle to the more famous Ngati Toa chief, Te Rauparaha.

far as I can tell, the first Maori to visit Argentina (or the United Provinces of the River Plate as it was then called) was the young nobleman Te Pehi Kupe in October 1824. (The name is spelt varyingly as Te Pēhi Kupe, Tupai Cupa, Te Pai Kupa, and Tippahée Cupa). Te Pehi was born on the North Island, probably around 1795, and was a senior-line descendant of Toarangatira (founder of the Ngati Toa tribe) as well as an uncle to the more famous Ngati Toa chief, Te Rauparaha.

Most of New Zealand was a bit of a mess at the time, as various Maori tribes fought each other for land to grow potatoes on. Te Pehi Kupe, being a chief and military leader, was desirous to go to Europe in order to obtain weapons for his tribe. When the British ship Urania went past the southern tip of the North Island, Te Pehi forced himself aboard despite the violent resistance of the ship’s officers and crew. When asked what he desired by the Urania‘s captain, Richard Reynolds, Te Pehi replied in broken English, “Go Europe, see King George”.

Captain Reynolds did not think this a good idea and, knowing the Maori to be good swimmers, tried to have him thrown overboard, but the native nobleman’s physical strength prevented this. (And a good thing, too, as Te Pehi managed to save the Captain from drowning later on in the journey.)

The Urania made its return to England with Te Pehi Kupe aboard, calling at Lima and then sailing around the Southern Cone, where they called in at Buenos Aires. George Thomas Love provides us with an account of the Maori’s arrival in A Five Years’ Residence in Buenos Ayres (published in 1827):

In the month of October, 1824, the visit of a New-Zealand chief to Buenos Ayres, by name Tippahée Cupa, attracted much curiosity; he arrived in the British ship Urania, Captain Reynolds. Tippahée came alongside this ship in Cook’s Straits, with a war canoe filled with his people, and, in spite of the remonstrances and even force used by Captain R. refused to quit the vessel, expressing his determination to proceed to England. He bade his followers an affectionate adieu, enjoining obedience to his successor during his absence. The Urania sailed for London with her passenger the 8th December, 1824.

Tippahée, when he first arrived in Buenos Ayres, was clothed in an old red coat, formerly belonging to a London postman. The English paid him many attentions, inviting him to dine at their houses, and new clothing him. His behaviour at table was easy and unembarrassed; and, when requested, he would perform the dances and war songs of New Zealand. He understood a little of the English language, and spoke a few words of it; his intelligent manners, and circumspect conduct, rendered him an universal favourite.

On the map he could trace the ship’s course from New Zealand to Lima and Buenos Ayres. He knew an Englishman immediately; the Spaniards he did not much admire, fancying they viewed him with contempt, and was glad to get among Englishmen. His age is about forty; he possesses amazing strength; his tattooed face and appearance always attracted a crowd after him in Buenos Ayres.

On board ship he was found very useful, doing all sorts of work, but he positively declined to go aloft. The fate of Captain Thompson, and the crew of the British ship Boyd, ought to bespeak caution in using coercion with these savage chieftains of New Zealand.

In Cruise’s book of New Zealand, Tippahee was shewn a picture of a chief of his country, with which he was greatly delighted. The object of his journey to England is to solicit arms and ammunition, to place him upon a par with a rival chief, who possesses those requisites.

In England, Te Pehi was indeed presented to King George IV. He also learned to ride, visited factories, was given many gifts, and survived the measles before leaving England aboard the Thames on 6 October 1825. In Te Pehi’s absence abroad, peace had been agreed between the Ngati Toa and their Ngati Apa rivals. Ngati Toa eyes soon turned to the South Island, and during the military campaign there Te Pehi Kupe was killed, his body cooked and eaten, and his bones turned into fish hooks.

Still, at least he enjoyed Buenos Aires before he died.

Some Aspects of the Fall of the Fourth Republic

(Only interesting, I’m afraid, to those reasonably acquainted with the situation of France in May 1958)

• The French-Algerian instigators of the military rebellion led by Salan didn’t know what to make of him when he was first appointed to Algeria so they decided, just to be on the safe side, to assassinate him on his first day on the job. Salan survived the bazooka attack on his office but his ADC was killed. The general later became the only socialist freemason to lead a right-wing terror group (the OAS).

• Once the Algiers rebellion commenced and travel between Algeria and metropolitan France was cut, many supporting figures made their way across the Mediterranean by whatever means at hand. Soustelle managed to escape his police guards and get to Algiers via a secretly chartered Swiss plane, but the more romantically inclined Roger Frey — later Minister of the Interior — first tried to get to Algiers on the actor Errol Flynn’s yacht. It didn’t pan out, and instead he was forced to hire the boat of an English ex-naval officer turned smuggler.

• The man in charge of wiretapping French telephones was unsure which side would emerge on top so cautiously refrained from giving the government the full picture of the information his wiretaps revealed.

• When Corsica was seized by the rebels, Moch, the Interior Minister, decided to send in the elite of the police force, the CRS. He was afraid, however, that military transport planes would fly them directly to Algeria, so he was forced to commission Air France planes instead. Upon landing in Corsica, the entire CRS contingent was met by the rebel parachute regiment and immediately defected to the rebellion.

• So widespread was the reluctance to support the government against the military rebels that even the meteorologists send false warnings of storms in the Mediterranean in the hopes of keeping the French Navy from moving against the rebels in Algiers.

• The air force was particularly keen for de Gaulle to take power, and took to flying planes in a Cross of Lorraine formation, as well as sending troop transport planes to Algeria in case they would be needed to invade mainland France.

• Regional military commanders in France varied in their loyalty to the government and sympathy for the rebels. One commander is alleged to have told the regional prefect “M. le Préfet, I am not here to defend your préfecture, but to take it.” Other prefects warned the cabinet that any orders for the police to arrest those suspected of aiding the rebellion might result in the prefects instead being arrested themselves.

• The government had sometimes ordered firemen to unleash their water hoses against rioters in the past. As popular support for the cabinet faded away, the head of the fire brigade felt compelled to inform ministers that his men would not take part in any anti-riot measures but would merely put out any fires that erupted. “And,” he said, referring to the home of France’s National Assembly, “in the Palais Bourbon, they wouldn’t bother.”

• As Philip Williams reports in his article “How the Fourth Republic Died”:

At that night’s cabinet Pleven summed up: “We are the legal government, but what do we govern? The Minister for Algeria cannot enter Algeria. The Minister for the Sahara cannot go to the Sahara. The Minister of Information can only censor the press. The Minister of the Interior has no control over the police. The Minister of Defence is not obeyed by the army.” Said a left-wing Gaullist in the Assembly, “You are not abandoning power — it has abandoned you.”

The Legacy of 1916

The commemoration of the 1916 rebellion takes place at Arbour Hill prison, where the earthly remains of the executed leaders of the Easter Rising were laid in a pit by the British military authorities. Some of the rebellion’s leaders who did not face the firing squad, most prominently Éamon de Valera and Countess Markievicz, founded Fianna Fáil ten years later in 1926.

Micheál Martin’s address is presented here without comment.

Every state should take time to commemorate and celebrate the people and events of their founding. This commemoration is organised by Fianna Fáil the Republican Party, but we come here as Irish men and women to fulfil our responsibilities to the great generation of 1916.

After 97 years their deeds resonate even more than ever. They saw an Ireland which should not accept limits on its future. They committed everything to the vision of a country with the right to shape its own destiny.

As we quickly approach the centenary of the Rising no one can doubt that the Irish people see the men and women of 1916 as noble and courageous. No one can question their central place in our history. (more…)

The Historical Sale at Adam’s

800 Years: Irish Political, Literary, and Military History – 18 April 2012

THE ANCIENT PRACTICE of lèche-vitrine is one hallowed by time and tradition. I remember one December day I had a lunch appointment with a friend who worked at the late, lamented Anglo-Irish Bank on Stephen’s Green in Dublin and, being early, I nipped a few doors down to the auction house Adam’s to engage in a bit of what I like to call thing-avarice (which the Germans probably have a word for). We do enjoy taking the occasional peek round the Dublin auction houses to see what’s what, and to examine the cabinet of curiosities that come out from ancient houses and rotting flats and appear in these bright places where commerce and refinement play their strange little waltz. When it comes down to it, though, it’s really just about having nice things — the sort of stuff you want lying around the house inexplicably.

Anyhow, the historical auction at Adam’s is coming up on 18 April and sure enough their senior rival Whyte’s is having a similar sale just a few days later on 21 April. We’ll only look at Adam’s here — if we considered Whyte’s as well, we’d be here all day. (more…)

Cardinal Manning

Over at Reluctant Sinner, Dylan Parry has an excellent post on Cardinal Manning, the second man to serve as Archbishop of Westminster. Manning is all too often forgotten, despite being one of the most widely loved and respected men of his generation. His funeral, famously, was the largest ever known in the Victorian era. Besides his wisdom at the helm of England’s most prominent see, the good cardinal’s greatest legacy might be his influence on Rerum Novarum, the great social encyclical of Leo XIII. Dylan is planning on writing further on the subject of Cardinal Manning, giving us something to look forward to. (more…)

A Breath of Fresh, Northern Air

The Dorchester Review Proves That Canada is Still Thinking

This summer I received an email from my friend Bruce Patterson, all-around nice guy and Deputy Chief Herald of Canada, informing me of a new historical and literary review just founded called the Dorchester Review. Intrigued, I obtained a copy and was pleasantly enthralled with what I found. The first issue of the Dorchester Review contained a variety of thoughtful articles on fascinating subjects. I spent an entire morning sitting comfortably on a café sofa and imbibing the intelligent and enlightening contents of the magazine.

The editors did issue a brief statement explaining the genesis of their new review. They had me at their Pieperian first sentence: “The Dorchester Review is founded on the belief that leisure is the basis of culture.”

Just as no one can live without pleasure, no civilized life can be sustained without recourse to that tranquillity in which critical articles and book reviews may be profitably enjoyed. The wisdom and perspective that flow from history, biography, and fiction are essential to the good life. It is not merely that “the record of what men have done in the past and how they have done it is the chief positive guide to present action,” as Belloc put it. Action can be dangerous if not preceded by contemplation that begins in recollection.

The endeavour of reviewing books, the editors acknowledge, has too often been reduced either to brief puff-pieces in the Saturday insert of the local paper or more high-minded but uncritical praise of like-minded academics for one another. “There are too few critical reviews published today, particularly in Canada, and almost none translated from francophone journals for English readers.” As someone with a lifelong love of Quebec, I am relieved that finally there is a review in my own language willing to take Quebec seriously.

“At the Review,” the editors continue, “we shall praise the good books and assail the bad.”

They also forthrightly explain their rejection of the narrow nationalist perspective that has been on the ascendant in Canada throughout the past century, especially since the foundation of The Canadian Forum. The Dorchester Review effectively throws Canada’s doors open to a more reasoned understanding of the country’s relationship with Europe (Britain and France particularly), America, the Commonwealth, and the world.

But the Dorchester Review is not a publication just for Canadians. There is a great deal of Canada in it, but also a great deal of the world. The second issue (just printed) features articles with titles such as “Why Marx is Still (Mostly) Wrong”, “1789: The First Counter-Revolutionaries”, “What Sort of Autocrats Were the Popes?”, “Can Vichy France Be Defended?”, and “The Scots Fight Back” (the last in response to an article in the first issue: “How the English Invented the Scots”).

Contributing editor Chris Champion is interviewed by CBC Radio here. A number of the contributors (Conrad Black, Paul Hollander, etc.) readers of The New Criterion will already be familiar with. The latest number also includes a book review by this, your humble and obedient scribe.

Head over to dorchesterreview.ca to find out more or subscribe.

A Rioplatense Kingdom?

New book explores the monarchic projects of the River Plate, 1808–1825

A book recently published in Buenos Aires sheds new light on the difficult transition period between the Spanish Empire on the River Plate and the foundation of the Argentine Republic. The launch party for Bernado Lozier Almazán’s Proyectos monárquicos en el Río de la Plata 1808-1825. Los reyes que no fueron (“Monarchic projects in the River Plate 1808–1825: The kings who weren’t”) was held recently in the Quinta ‘Los Ombúes’, home of the municipal library, museum, and archives of San Isidro, the city in the Provincia de Buenos Aires known as Argentina’s ‘Rugby Capital’.

Proyectos monárquicos highlights the forgotten truth that most of the Argentine ‘patriots’ — San Martín, Belgrano, and Alvear among them — were monarchist, not republican. Proposals involving the courts of Spain, Portugal, France, and even England were proffered, and there was even an interesting proposal to marry a European prince to an Incan princess and offer him the throne of the Río de la Plata. (more…)

Cape Town’s ‘Nazi’ Street to be Renamed

Oswald Pirow Street will rechristened after Dr. Christiaan Barnard

The city of Cape Town has recently effected a small number of street name changes decided at the end of last year. The N2 route as it heads into the centre of the city, currently called Eastern Boulevard, will be renamed Nelson Mandela Boulevard. The open square between the opera house and the city offices will be renamed Albert Luthuli Place. Most significantly, Oswald Pirow Street on the Cape Town foreshore will be renamed Christiaan Barnard Street.

city of Cape Town has recently effected a small number of street name changes decided at the end of last year. The N2 route as it heads into the centre of the city, currently called Eastern Boulevard, will be renamed Nelson Mandela Boulevard. The open square between the opera house and the city offices will be renamed Albert Luthuli Place. Most significantly, Oswald Pirow Street on the Cape Town foreshore will be renamed Christiaan Barnard Street.

The renaming of streets and other places in South Africa has proved a controversial and unsettling task. Many streets named after leading figures associated with the 1948-1990 apartheid regime remain. In 2001, the New National Party (NNP) mayor of Cape Town, Peter Marais, attempted to rename Adderley Street and Wale Street after Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk respectively. But Marais’s plan provoked a surprising public backlash, as well as opposition-for-opposition’s sake from the local ANC. The proposed ‘Nelson Mandela Avenue’ had already been renamed once: originally Heerengracht, the grateful citizens of Cape Town rechristened it Adderley Street in 1850, as a token of thanks to Charles Bowyer Adderley MP (later 1st Baron Norton) for his successful campaign against turning the Cape into a penal colony. (more…)

Senator Eugene McCarthy: A Kirkian Anecdote

Russell Kirk, the great St Andrean and American man of letters, relates this anecdote in his article “Will American Caesars Arise?” (Modern Age, Summer 1989):

The most interestingly complex of all recent aspirants to the presidency, [Senator Eugene] McCarthy obdurately called himself a liberal during years when that appellation was sinking swiftly in popular favour – although he abjured all forms of liberalism earlier than Franklin Roosevelt’s. (During the past few years, as he now remarks, he has employed the word ‘‘liberal’’ as an adjective merely.) In his political theories, actually, McCarthy has been a conservative: He declared long ago that Edmund Burke was his political mentor, and no one has more warmly praised Tocqueville. He has read seriously and written intelligently. In the White House – per impossibile – he might have turned the most imaginatively conservative of Presidents.

Or perhaps not. Once upon a time I had an assistant who was a graphoanalyst, an expert on handwriting. Having examined a specimen of Senator McCarthy’s handwriting, my assistant pronounced him rebellious, a hard master, and desirous of power. A touch of Caesar even in Caesar’s adversary? However that may be, McCarthy’s only considerable assertion of power was his unseating of President Johnson by running a good second in the New Hampshire primary of 1968.

A congenital no-sayer, Eugene McCarthy never ran with the hounds. He was candid and witty always. He and I first met as debaters before a large audience, in Boston. After this exchange, sponsored by the Paulist Fathers, a reception was held for us. Up to Senator McCarthy came a zealous young Paulist, inquiring, “Senator McCarthy, don’t you think that Jack Kennedy is the finest president this nation ever has had?” (This occurred during the first year of the Kennedy administration.)

“No,” said McCarthy, unsmiling.

Although taken aback, the Paulist returned to the charge: “But surely you agree, Senator, that President Kennedy has given this nation a new hope, a new vigor, a sense of moving forward toward great things?”

“No,” said Eugene McCarthy.

The Paulist persisted: “But of course you’ll agree with me when I say, Senator, that the Kennedy family have brought to our life a culture, a refinement, a meaningfulness, that we have not known before.”

“No,” said Eugene McCarthy.

“But – but Senator McCarthy, surely Jack Kennedy is a very nice man personally?”

Eugene McCarthy turned his back upon the Paulist and slowly walked away. He knew how to say no, he was not ensnared by cliché and slogan, and he had a poet’s attachment to truth.

Nobility and Dignity at the Café Valois

Farewell, O good old days! Farewell, O affable visage of the proprietor and smiling and respectful reception of the waiters! Farewell, O solemn entries of the Café Valois’ dignified customs, which people were curious to see. Such was the case with the Knight Commander Odoard de La Fere’s arrival.

At exactly noon, the canon of the Palais-Royal heralded his arrival. He would appear on the threshold and pause for a moment to sweep the salon with an affable and self-assured gaze as someone eager to practice a longtime custom. His right hand pressing firmly on the white and blue porcelain handle of his cane, he threw his old faded brown cape over his shoulder with a swing of his left hand. No one ever snickered at this, since not even the most elegant mantle with golden fleur-de-lys embroidery was ever thrown back with a more distinguished movement.

In 1789 the former steward of the Prince of Conti ran the Café Valois; it was rather devoid of political colour and local flavor at that time.

Among the frequenters of the place, standing out by his noble manners, stately demeanor and wooden leg, was the Chevalier de Lautrec. He was from the second line of that family, an old brigadier of the king’s army, a Knight of Malta, of Saint Louis, of Saint Maurice and of Saint Lazare.

The Chevalier de Lautrec was a middle-aged man who lived a modest, though very dignified life on his small pension. Though he rarely appeared in society, he could be seen most often at the Palais Royal and the Café Valois. He was a very cultured mind and an assiduous reader of all the newspapers.

Deprived of his pension overnight, it was never known what the Chevalier de Lautrec lived on at a time when it was so difficult to live, and so easy to die. But here we have something that sheds at least a dim light on this mystery.

One morning after finishing a very modest breakfast in the Café Valois, as was his custom, the Chevalier de Lautrec rose from his table, chatted with all naturalness with the proprietress, who stood behind a counter, bid good-day to the master of the café with a slight gesture of the eyes, and walked out majestically saying nothing about the bill. (more…)

Imperial Mexico

The Forgotten Monarchs that Shaped a Great Nation

THE NEW WORLD has such a republican reputation these days. Even though there remain thirteen monarchies in the Americas, concentrated in the Caribbean, there are only three monarchs between them (all, curiously, women: Elizabeth II, Beatrix, and Margrethe II). But it’s usually forgotten that the Americas have had two great empires of their own: the Empire of Brazil in South America and the Empire of Mexico in North America.

Napoleon’s Peninsular War in Spain had caused quite a ruckus in the Spanish Americas, where liberals had seized the opportunity to wage long, rebellious wars of independence with fluctuating levels of popular support. In Mexico, two of the rebel generals, Agustín de Iturbide and Vicente Guerrero composed a plan to change the balance of power in the Spanish empire as a whole while simultaneously securing Mexican independence. The three main aims of the ‘Plan of Iguala’ were: 1) Catholicism as the established religion, 2) The independence of Mexico, and 3) The end of legal distinctions between the races; summed up as “Religión, Independencia, y Unión”.

But the larger scheme of the Plan was to convince King Ferdinand VII to move to Mexico and become Emperor of Mexico, shifting the center of power in the Spanish empire from Madrid to Mexico City. If Ferdinand would not accept, then the crown would be offered to his brother and the rest of his family down the line until someone accepted, or if even that failed then to a member of another European dynasty. (more…)

Olympic Teams of Yesteryear

The vanished lands and failed alliances of the Modern Olympiad

THE GAMES OF THE Modern Olympiad are events which are meant to bring the peoples of the world together in peace and harmony and all those good and heartening things, but from the very beginning they have gotten bogged down in the petty particularities of rival nations, which altogether makes them rather more fun and interesting, if perhaps a touch less high-minded. The story of the ancient gathering’s revival in 1896 through the efforts of Pierre Frédy, Baron de Coubertin is well-known. Athletes from at least fourteen countries participated in those first modern games in Athens over a century ago, though the concept of national teams was not introduced until the 1906 games (the Intercalated Games, which have since been de-recognised by the IOC). But since those first games towards the end of the nineteenth century, the fortunes of many lands have waxed and waned, and likewise the spirit of unity amongst various peoples vied with the spirit of distinctiveness. Here, then, are but a small sample of Olympic teams which once vied for gold but which can no longer be found among the Olympic competitors of today. (more…)

The Houses of Parliament, Dublin

The Physical Incarnation of Ireland’s Golden Age

THE OLD HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT in Dublin are probably at the top of my list of favourite buildings in the world. Now the headquarters of the Bank of Ireland, it has a long and varied history, and its exterior composition is one of surprising unity for a structure the components of which were designed by three architects. It is supposedly the first purpose-built parliament building in the world, and stands on the site of Chichester House, a stately home adapted for use by the Irish Parliament from the 1600s onwards.

The location, with a history dating back centuries, is just south of the Liffey river upon what was then known as Hoggen Green. A nunnery existed on the site which was supressed during Henry VII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. A large private house was then built on the site, set back from the street, eventually known as Chichester House. (It likely incorporated some of the old convent’s structure). Among the esteemed inhabitants of the house were Sir George Carew, sometime Lord President of Munster, Sir Arthur Chichester, after whom the house was named, and the Anglican Bishop Edward Parry is known to have had a lease on the place during his lifetime.

The building must have been seen as holding some public significance, not only because it was located adjacent to the University of Dublin (of which Trinity College is the sole constituent institution), but it was home to the Irish Law Courts for a time beginning with the Michaelmas legal term of 1605. Towards the end of the seventeenth century, no later than October 1692, the Irish parliament began to meet at Chichester House on College Green. (more…)

Hapsburg Hebraica

After the passing of the Hapsburg empire, which had been so protective of its Jewish subjects (especially compared to the regimes which succeeded it), numerous prominent Jews were received into the Catholic faith, perhaps having come to a full appreciation of precisely what they had lost. The subject of “Literary Jewish Converts to Christianity in Interwar Hungary” is worthy of further investigation (some graduate student should write a dissertation on just such a matter). I am no longer surprised when, in my researches, I come across yet another fascinating Hungarian Jew — be he a writer, playwright, poet, or patron — and discover, usually buried in some footnote, that he died a good Catholic.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories