History

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Stockholm in the Swinging 60s

The Solemn Opening of the Riksdag was the state opening of Sweden’s parliament, seen here in a recording from 1960 during the reign of Gustaf Adolf. Years ago I wrote about Oskar II’s opening of parliament.

Alas, all this was done away with as part of the constitutional innovations of 1974, and the Swedish legislature is now opened with a much simpler ceremony.

via Karl-Gustel

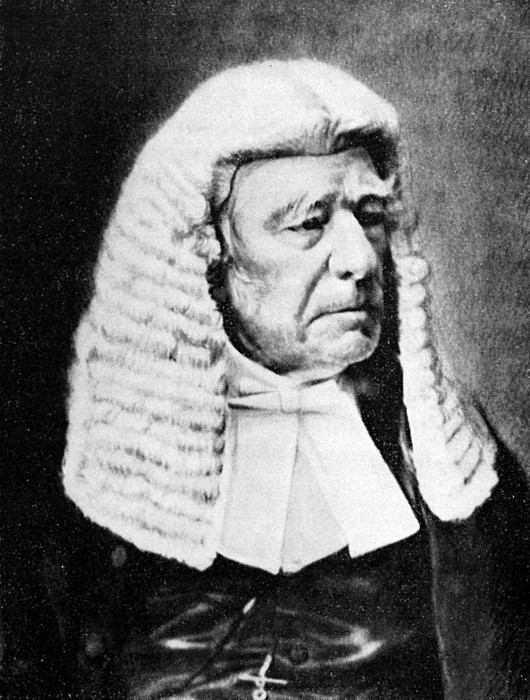

Sir Christoffel Brand

Look at that cragly visage! It belongs to Sir Christoffel Brand, the first Speaker of the House of Assembly in the Cape Parliament.

Brand was born in Cape Town in 1797 and left for the Netherlands in 1815, where he studied at Leiden. In 1820 he was awarded a doctorate in law based on his dissertation Dissertatio politico-juridica de jure coloniarum on the legal relationship between colonies and the metropole, and returned to the Cape. (more…)

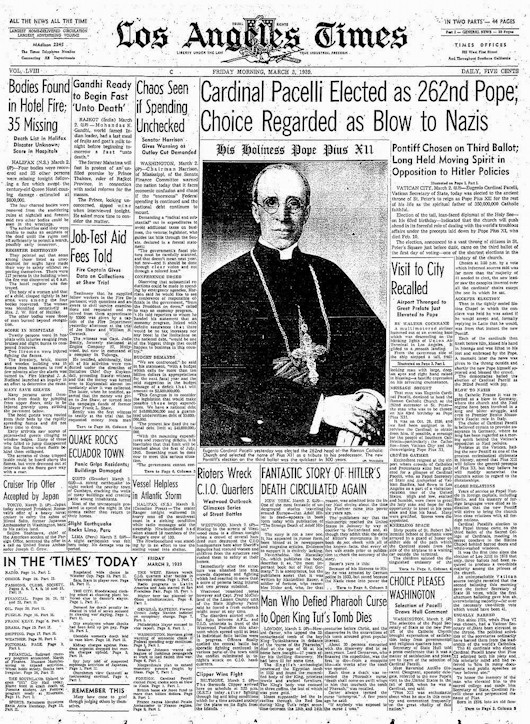

The L.A. Times on Papa Pacelli

How News of the Election of Pius XII was Received in 1939

The case against Pope Pius XII, accusing him of complicity in the crimes of Nazism, has been so thoroughly debunked — by Jews like Gary Krupp and Rabbi Dalin more than any — that it is no longer even worth refuting.

Still, it’s interesting to read the Los Angeles Times’s coverage of his election as Supreme Pontiff in the difficult year of 1939:

BLOW TO NAZIS

… The choice of Cardinal Pacelli is believed certain to provoke annoyance in Germany, where he long has been regarded as a moving spirit behind the Vatican’s opposition to Nazi policies.

As the news report goes on to note, Cardinal Pacelli was elected in only three ballots — the quickest papal election since that of Leo XIII in 1878.

Christmas on College Green

There are some good (if brief) shots of the Irish House of Lords chamber in this Christmas ad for the Bank of Ireland, 0:35-0:45.

The former Irish Houses of Parliament on College Green in Dublin were the first purpose-built parliament building in the world, and were purchased by the Bank of Ireland after the parliament was abolished by the Act of Union in 1800.

Unfortunately a condition of sale was demolishing the elegant octagonal Commons chamber at the centre of the building, to prevent it being used in the effort to have the Act of Union repealed.

Sir Thomas Cusack (1505-1571) has the distinction of having at times served as the presiding officer of both the upper and lower houses of the Irish Parliament. From 1541-1543 he was as Speaker of the House of Commons, in which role some scholars argue he was a prime mover behind the legislation erecting Ireland as a kingdom.

In the following decade he served as Lord Chancellor of Ireland, presiding in the House of Lords, from 1551 until 1555 when revelations about his involvement in the creative finances of Sir Anthony St Leger’s viceregal regime brought about Sir Thomas’s dismissal and (temporary) imprisonment.

He returned to favour when the Earl of Sussex was appointed viceroy, but never again held high office.

Of course, all that was before this neoclassical building was erected, when Parliament met mostly in Dublin Castle.

Marinus Willett

In one of the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum’s American wing, behind the Tuckahoe-marble façade of the old Assay Office (moved here from Wall Street), hangs this portrait of Col. Marinus Willett of the Continental Army’s 5th New York Regiment.

Born in 1740, the second of thirteen children, Willett attended King’s College before being commissioned a lieutenant in a New York provincial regiment during the Seven Years’ War (or French and Indian War as it’s known more locally). (more…)

Mendicant Architecture in Mediaeval Oxford

An interesting video from two American academics on the subject of Mendicant architecture in mediaeval Oxford, with some three-dimensional theoretical reconstructions of the Dominican and Franciscan houses in the city.

Both orders returned to Oxford in the twentieth century. The Capuchins refounded Greyfriars in 1910 and it was recognised as a permanent private hall (PPH) of the University in 1957. Its end as an academic institution was announced sadly on its fiftieth anniversary in 2007, but Greyfriars continues as a Capuchin friary.

Blackfriars under the Dominicans is still going strong, exercising a triple function as a priory of the Order of Preachers, a house of studies for the English province of the Order, and a PPH of the University of Oxford.

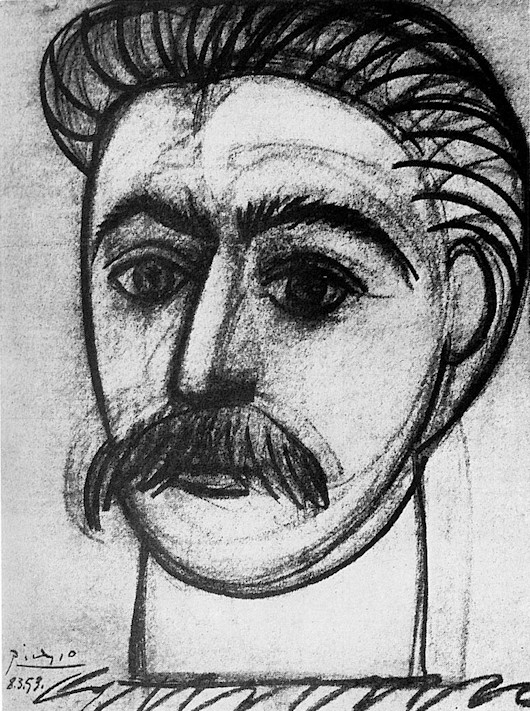

The Death of God the Father

When Stalin’s death was announced on Friday, 7 March 1953, Aragon called in Pierre Daix and rattled off a shopping list of features to honour Stalin in a special issue of Les Lettres françaises. […] Since Picasso had always refused to do a portrait of Stalin from a photograph, Daix sent a telegram to him at Vallauris saying, ‘Do whatever you want,’ and signed it ‘Aragon’.

Picasso’s drawing of Stalin, which depicted him as a curiously open-eyed young man, arrived at the very moment Les Lettres françaises went to press. Daix took the picture to Aragon. He admired it and said that the party would appreciate the gesture. While it was being set into the front page, office boys and typists crowded round the picture. Everyone thought it ‘worthy of Stalin’.

Daix was overjoyed to be the one who had commissioned Picasso’s first portrait of the Soviet leader and rushed it down to the printers. But a few hours later, when the edition had been run off, the mood in the building had completely changed to one of fear. Journalists from L’Humanité, passing by, spotted the drawing and cried out that it was unthinkable that any Communist publication should consider such a representation of ‘le Grand Staline’.

Pierre Daix promptly rang Aragon at his apartment; Elsa Triolet answered. She told him angrily that he was mad to have even thought of asking Picasso for such a drawing.

‘But really, Elsa,’ Daix broke in, ‘Stalin isn’t God the Father!’

‘Yes, he is, Pierre. Nobody’s going to reflect much about what this drawing of Picasso signifies. He hasn’t even deformed Stalin’s face. He’s even respected it. But he has dared to touch it. He has actually dared, Pierre, don’t you understand?’ […]

Antony Beevor & Artemis Cooper (1994, London)

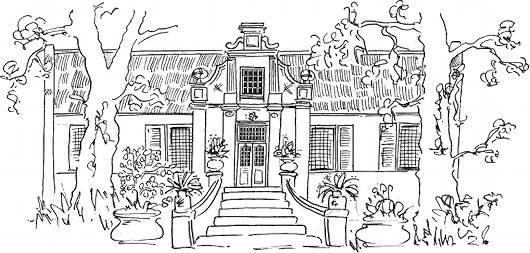

Muratie

The Stellenbosch estate of the artist Georg Paul Canitz

We had supper with Mr. Canitz, the painter, one Sunday night, by the light of candles in a fine Dutch candelabra, and drove back to Stellenbosch in moon light which had transformed the countryside into the most entrancing fairyland imaginable.

Great clumps of trees in unexpected places gave an eeriness to the white ribbon of road which stretched across the valley. The soft evening breeze of magic scents lulled us, and we drowsed to the hum of the car bearing us homeward.

That memory is still vivid to me so I shall turn from our Golden Road, and “…muse awhile, entoil’d in woofed phantasies.”

So the architect Rex Martienssen described a visit to Muratie, the home of the artist Georg Paul Canitz, in 1928. Canitz was a Saxon, born in Leipzig, where his parents had hoped he would pursue a military career. Both his zeal and talent as an artist appeared early on, and so he ended up at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. After further studies in Italy, Paris, and the Netherlands, a chest ailment drove him to the interior of Südwestafrika in 1907.

Canitz healed quickly in the dry air but could not find a cure for the striking beauty of the new world around him. His wife and children were summoned from Germany, and three years later he moved to Stellenbosch after falling in love with the “City of Oaks”.

Canitz devoted himself to his passions: riding, painting, and teaching (both at his own art school and at the University). Riding to a party at Knorhoek one day he stumbled upon the little house and farm at Muratie and was quickly enamored of the place. It wasn’t long before he had purchased it and moved his family there.

G P Canitz

At Muratie, the painter developed a further art: that of winemaking. In this he was assisted by the legendary Dr Perold — first chair of viticulture at Stellenbosch. Canitz became a pioneer of the pinot noir grapes which have since become a South African staple. Perhaps even more he developed the skills of a kind and generous host, for which he was well reputed throughout South Africa. He would welcome friends and guests — among them Martienssen and his architectural students as cited above — throughout the year. In warmer months they came for the swimming pool and the breezy stoep, while in winter a fire awaited, or perhaps a few rounds of strong drink in the Kneipzimmer.

I like to think this was Canitz’s favourite room at Muratie: bedecked with benches, the light streaming in through a stained-glass windows, and the walls covered in naturalistic painting as well as graffitied signatures and sayings in German, Afrikaans, French, and Greek.

The painter died in 1958, leaving Muratie to his daughter, who in 1987 sold it to members of the Melck family who had owned it from 1763 to 1897. (The house was first built in 1685.) I suspect Canitz would have greatly appreciated his handiwork being passed back to those who had looked after the place for many generations before him. The Melcks, unsurprisingly, have a great reverance for the history of the estate. They even go so far as to leave the cobwebs which have accrued go undisturbed and ask visitors to do likewise.

And, even today, the wine still flows!

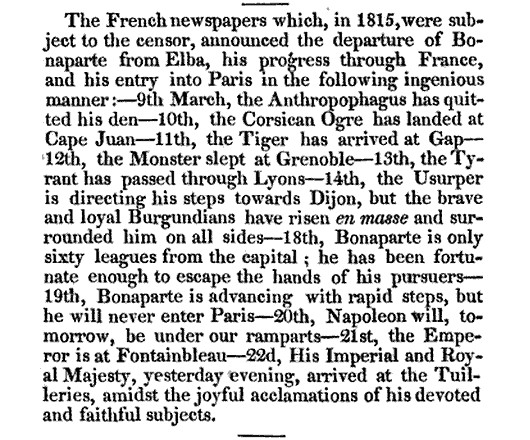

The Anthropophagus Has Quitted His Den

The Museum of Foreign Literature Science and Arts was a Philadelphia periodical edited by the prodiguously talented and unjustly neglected Eliakim Littell.

In January 1831 his review published this little snippet of headlines claimed to have been clipped from French newspapers:

The French newspapers which, in 1815, were subject to the censor, announced the departure of Bonaparte from Elba, his progress through France, and his entry into Paris in the following ingenious manner:

March 9 THE ANTHROPOPHAGUS HAS QUITTED HIS DEN

March 10

THE CORSICAN OGRE HAS LANDED AT CAPE JUAN

March 11

THE TIGER HAS ARRIVED AT GAP

March 12

THE MONSTER SLEPT AT GRENOBLE

March 13

THE TYRANT HAS PASSED THOUGH LYONS

March 14

THE USURPER IS DIRECTING HIS STEPS TOWARDS DIJON

but the brave and loyal Burgundians have risen en masse

and surrounded him on all sidesMarch 18

BONAPARTE IS ONLY SIXTY LEAGUES FROM THE CAPITAL

He has been fortunate enough to escape the hands of his pursuersMarch 19

BONAPARTE IS ADVANCING WITH RAPID STEPS

But he will never enter ParisMarch 20

NAPOLEON WILL, TOMORROW, BE UNDER OUR RAMPARTS

March 21

THE EMPEROR IS AT FONTAINEBLEAU

March 22

HIS IMPERIAL & ROYAL MAJESTY, yesterday evening, arrived at the Tuileries, amidst the joyful acclamation of his devoted and faithful subjects.

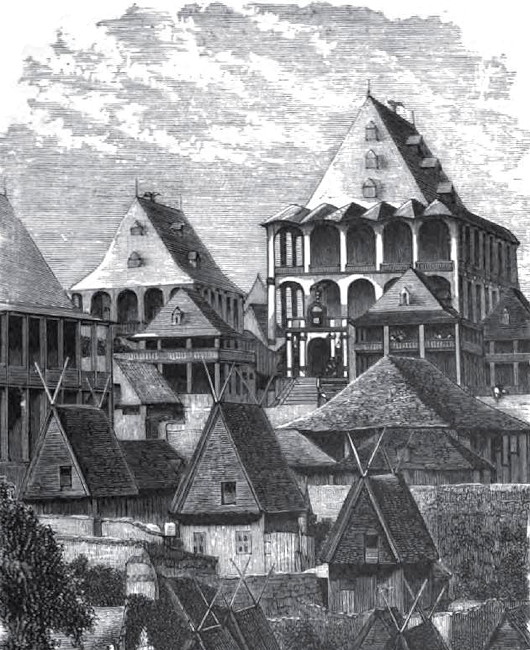

In the Old Dutch East Indies

Little Holland’s rule over this vast land – today the world’s largest Muslim country by population – never loomed large in the European imagination (the Netherlands excepted) and thus has been too easily forgotten. Peter van Dongen’s Rampokan series of graphic novels (in Herge’s ligne-claire style) is the most prominent recent attempt to shine some light on the Dutch East Indies and it has obtained a bit of a cult following.

The colonial architecture went through the usual transformations, from awkward hybrids of the motherland and the vernacular to a cool and crisp classical elegance of the later imperial buildings. Henri Maclaine Pont’s work at Bandung is probably the most successful Dutch take on local building traditions, and in some ways Geoffrey Bawa is his spiritual offspring.

The ministries of Indonesia’s government still convene in elegant Dutch colonial buildings, though the names have all changed. The Daendels Palace is now the Finance Ministry, Buitenzorg is now Bogor, and the old Koningsplein is now the Medan Merdeka or Freedom Square. (more…)

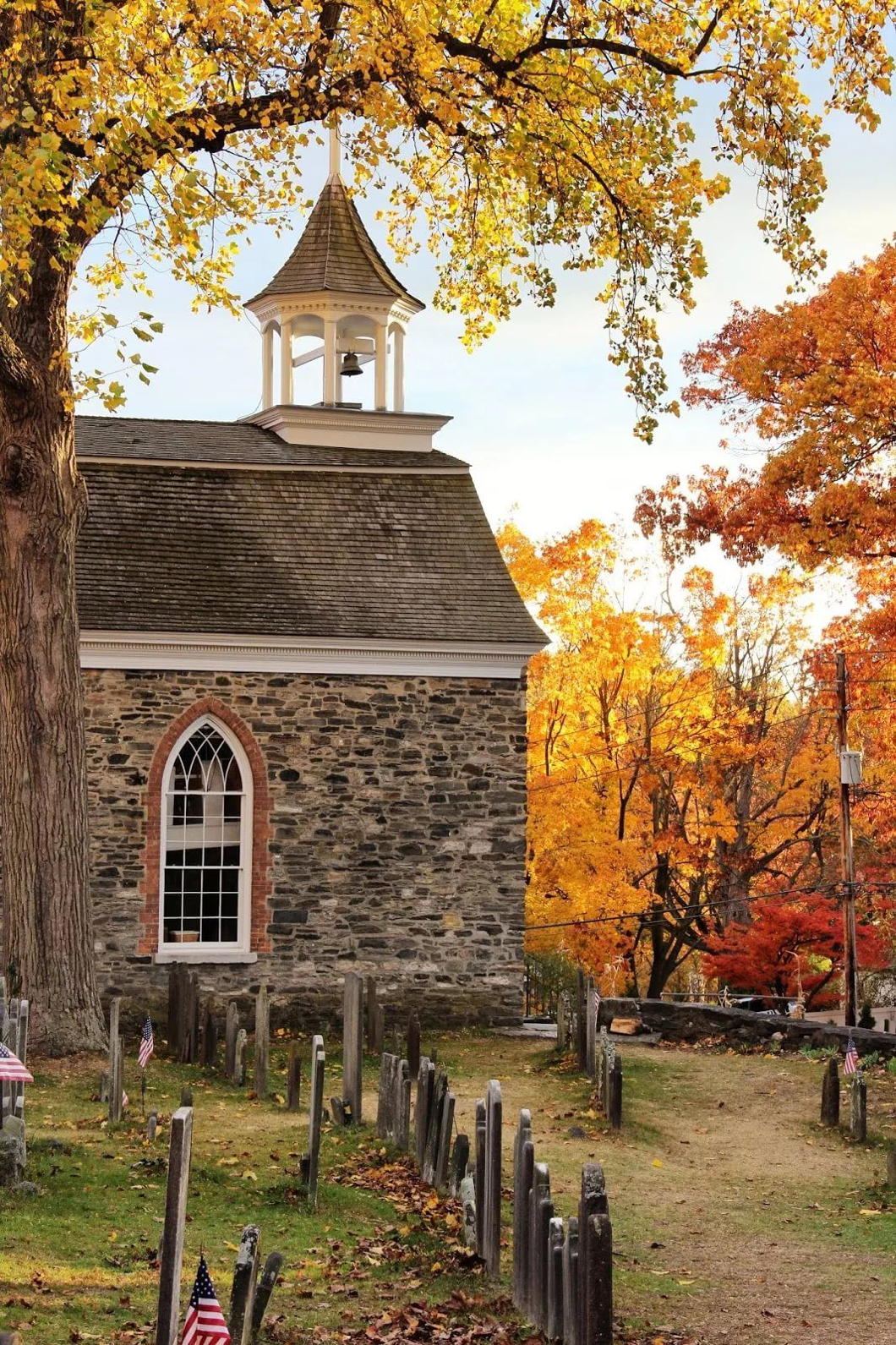

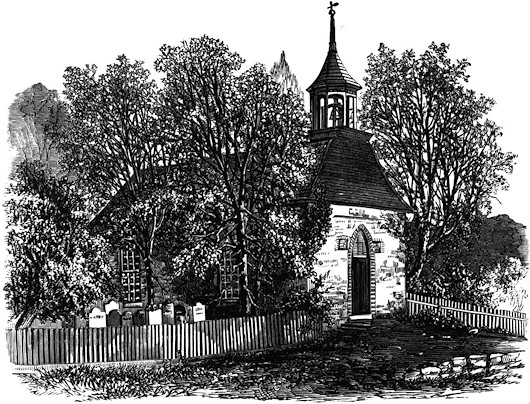

The Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow

If there is any season which is plus New-Yorkaise que les autres then it must be autumn, and around the time of Hallowe’en in particular.

Thanks to the fertile imagination of Washington Irving, buried in the cemetery of the Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow, the Hudson Valley is the spiritual home of this ancient Celtic feast now implanted in the New World.

The other day I dusted off the huge single-volume complete works of Irving – almost the size of an old Statenvertaling – and re-read his most famous tale, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”.

Irving describes the position of the Old Dutch Church:

The sequestered situation of this church seems always to have made it a favorite haunt of troubled spirits. It stands on a knoll surrounded by locust trees and lofty elms, from among which its decent whitewashed walls shine modestly forth, like Christian purity beaming through the shades of retirement. A gentle slope descends from it to a silver sheet of water bordered by high trees, between which peeps may be caught at the blue hills of the Hudson. To look upon its grass-grown yard, where the sunbeams seem to sleep so quietly, one would think that there at least the dead might rest in peace.

On one side of the church extends a wide woody dell, along, which raves a large brook among broken rocks and trunks of fallen trees. Over a deep black part of the stream, not far from the church, was formerly thrown a wooden bridge; the road that led to it and the bridge itself were thickly shaded by overhanging trees, which cast a gloom about it even in the daytime, but occasioned a fearful darkness at night. Such was one of the favorite haunts of the Headless Horseman, and the place where he was most frequently encountered.

The tale of the Headless Horseman is now, partly thanks to various popular reinterpretations of it, well known even outside the Hudson Valley. I remember as a wee lad growing up in that part of the world our Scout uniforms had a badge bearing the image of the “Galloping Hessian”.

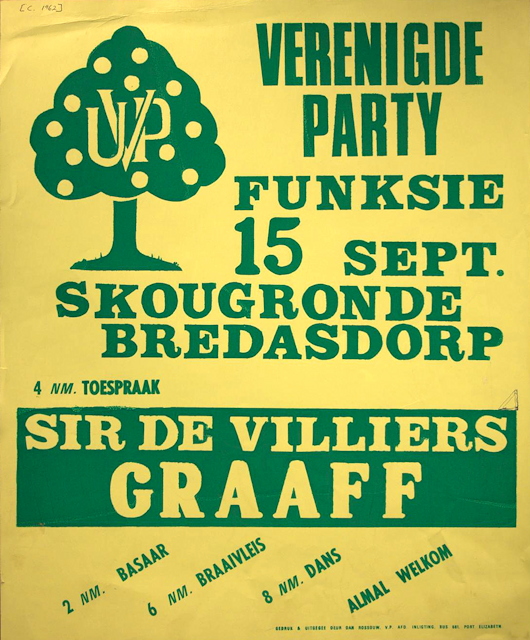

Party in the Overberg

Alongside a bazaar, a braai, and dancing, a speech by Sir De Villiers Graaff is the selling point of this poster advertising a United Party (Verenigde Party) get-together in the beautiful Overberg region of the Cape.

“Sir Div” was the inheritor of one of only twelve South African baronetcies and led his party from 1956 until 1977 when it merged with the Democratic Party of verligte ex-Nationalists to form a new entity.

The broadly centrist party had lost power to the republican Nats (creators of apartheid) in 1948, and suffered splits that led to the creation of the Liberal Party and the United Federal Party in 1953, the National Conservative Party in 1954, and the Progressive Party in 1959.

The party’s emblem was a happy little citrus tree.

An Old Name Returns to Banking

or: What Daniel O’Connell has to do with the 2008 Banking Crisis

Daniel O’Connell was a remarkable man by any stretch of the imagination, and is most often recalled for his part in bringing about the Relief Act of 1829 which emancipated the Catholics of Great Britain and Ireland from an officially oppressed legal status. Among his many achievements, however, was in London in 1825 founding the National Bank of Ireland.

As the RBS Group’s website notes, O’Connell:

…helped draw up the agreement that established it, spoke at public meetings to drum up support for it, invested in it, attended its first board meetings and, in 1836, was appointed its governor. He became an important figurehead for the new bank and there was even a proposal, not implemented, to put a bust of O’Connell on the bank’s notes.

The National Bank was created with the aim of injecting cash into the rural economy in Ireland, and its charter ensured that half of its returns would accrue to local shareholders in the country. O’Connell, not the best manager of financial affairs, ended up accruing huge personal debts to the bank and had to be quietly bailed out by several others (commencing a tradition of surruptitious banking amongst the nation’s major politicians).

Anyhow, the National Bank expanded across Britain and Ireland. In 1966 its Irish core was sold to the Bank of Ireland, and the English and Welsh branches were acquired by the National Commercial Bank of Scotland (which was a 1959 merger of the National Bank of Scotland and the Commercial Bank of Scotland). This, in turn, merged into the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1969, with the superfluous National Bank branches being turned into Williams & Glyn’s Bank the following year. (more…)

Flag of an African Slaver

c. 1862-1866; hand-sewn cotton; 9 ft 2 in x 15 ft

Greenwich, London

The simple image of an African, garments aflutter, on a plain background provides a strikingly modern design as the commercial emblem of a firm engaged in the trade in human misery.

This flag was captured by Commodore Arthur Eardley-Wilmot while on anti-slavery operations off West Africa and given to his friend William Henry Wylde who supervised anti-slave-trade efforts at the Foreign Office in Whitehall.

The eradication of the slave trade is arguably the greatest peacetime achievement of the Royal Navy as well as powerful proof that the supremacy of economics can be overcome and made subject to morality. This is not just a possibility, but a necessary precondition for any humane and civilised order in society.

Smuts at Leiden

For quite some time, Leuven — in what is currently known as Belgium — was the only university in the Netherlands. It is still (barely, some argue) a Catholic university, and after the Protestant revolt sealed its rule over the northern part of the Dutch realms, William the Silent founded a university at Leiden as a Calvinist academy in 1575.

Leiden University has had strong links with South Africa from the earliest days. Ds. Johannes de Vooght — in the 1660s, the second leraar of Cape Town’s Dutch Reformed congregation — studied here, as did numerous predikante of that period and onwards, including Ds. Petrus van der Spuy, the first NGK minister to be born in South Africa.

South African politicians studied here aplenty: Sir Christoffel Brand (first Speaker of the Cape Parliament); Jan Brand (fourth president of the Orange Free State); Marthinus Steyn (sixth and final president of the O.F.S.); and Nicolaas Diederichs (third staatspresident of the Republic of South Africa).

Probably the first South African to be granted an honorary degree by Leiden (c. 1830) was Antoine Changuion, the founder of the Dutch language movement which advocated preserving Dutch as the cultural language of the Afrikaners against the emerging Afrikaans.

It was in 1948 that Leiden granted the greatest Afrikaner — Field Marshal Smuts — a Doctorate of Law honoris causa. Smuts was on his way back from Cambridge where he had been granted the honour of being installed as Chancellor of the University. Even Die Burger, a Nationalist paper opposed to his Verenigde party, found the event worthy of a caustic near-compliment:

“We may differ from him on many issues, but the honour which he has won for the Afrikaner does not leave us untouched.”

Wednesday 27 January

– Margaret Beaufort was one of the greatest women England ever produced, but her legacy has been plagued by misogyny combined with Protestant suspicion of her Catholic piety. Leanda de Lisle delves into the question of whether she was a hero or a villain.

– Speaking of powerful women, James Panero’s examines the monument to Joan of Arc on New York’s Riverside Drive. The artist was a female sculptor, Anna Hyatt Huntington, whose statue of El Cid in the forecourt of the Hispanic Society on Audubon Terrace is one of the finest sculptural arrangements in the New World.

– Lent is about to stare us in the face, but so far as I am concerned we are allowed to wallow in Christmas cheer until Candlemas comes on 2 February. Dr John C Rao (of St John’s University and the Roman Forum) offers us a reflection on the Christmas Crèche and its origins as Saint Francis’s giant “F.U.” to Cathar heretics, while putting the thinking behind that great saint’s actions in a modern context.

– It’s good to see neglected favourites receive a bit of unexpected attention. One such is the Irish writer George Russell, more often known by his pen name ‘Æ’. The Irish Ambassador to Great Britain, Dan Mulhall, begins a series on Irish writers and 1916 by looking at Æ in the context of the Rising.

One project that TCD or UCD – or anyone for that matter – needs to take on is digitising the entirety of The Irish Statesman, the journal mostly edited by Russell which presented a fascinating counterpoint to the more common narratives, first in 1919/20 and then from 1922 to 1930.

– And finally, some Goethe love from The New Yorker’s Adam Kirsch.

Darkness

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day,

And men forgot their passions in the dread

Of this their desolation; and all hearts

Were chill’d into a selfish prayer for light:

And they did live by watchfires—and the thrones,

The palaces of crowned kings—the huts,

The habitations of all things which dwell,

Were burnt for beacons; cities were consum’d,

And men were gather’d round their blazing homes

To look once more into each other’s face;

Happy were those who dwelt within the eye

Of the volcanos, and their mountain-torch:

A fearful hope was all the world contain’d;

Forests were set on fire—but hour by hour

They fell and faded—and the crackling trunks

Extinguish’d with a crash—and all was black.

The brows of men by the despairing light

Wore an unearthly aspect, as by fits

The flashes fell upon them; some lay down

And hid their eyes and wept; and some did rest

Their chins upon their clenched hands, and smil’d;

And others hurried to and fro, and fed

Their funeral piles with fuel, and look’d up

With mad disquietude on the dull sky,

The pall of a past world; and then again

With curses cast them down upon the dust,

And gnash’d their teeth and howl’d: the wild birds shriek’d

And, terrified, did flutter on the ground,

And flap their useless wings; the wildest brutes

Came tame and tremulous; and vipers crawl’d

And twin’d themselves among the multitude,

Hissing, but stingless—they were slain for food.

And War, which for a moment was no more,

Did glut himself again: a meal was bought

With blood, and each sate sullenly apart

Gorging himself in gloom: no love was left;

All earth was but one thought—and that was death

Immediate and inglorious; and the pang

Of famine fed upon all entrails—men

Died, and their bones were tombless as their flesh;

The meagre by the meagre were devour’d,

Even dogs assail’d their masters, all save one,

And he was faithful to a corse, and kept

The birds and beasts and famish’d men at bay,

Till hunger clung them, or the dropping dead

Lur’d their lank jaws; himself sought out no food,

But with a piteous and perpetual moan,

And a quick desolate cry, licking the hand

Which answer’d not with a caress—he died.

The crowd was famish’d by degrees; but two

Of an enormous city did survive,

And they were enemies: they met beside

The dying embers of an altar-place

Where had been heap’d a mass of holy things

For an unholy usage; they rak’d up,

And shivering scrap’d with their cold skeleton hands

The feeble ashes, and their feeble breath

Blew for a little life, and made a flame

Which was a mockery; then they lifted up

Their eyes as it grew lighter, and beheld

Each other’s aspects—saw, and shriek’d, and died—

Even of their mutual hideousness they died,

Unknowing who he was upon whose brow

Famine had written Fiend. The world was void,

The populous and the powerful was a lump,

Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless—

A lump of death—a chaos of hard clay.

The rivers, lakes and ocean all stood still,

And nothing stirr’d within their silent depths;

Ships sailorless lay rotting on the sea,

And their masts fell down piecemeal: as they dropp’d

They slept on the abyss without a surge—

The waves were dead; the tides were in their grave,

The moon, their mistress, had expir’d before;

The winds were wither’d in the stagnant air,

And the clouds perish’d; Darkness had no need

Of aid from them—She was the Universe.

This year — 2016 — will be the two-hundredth anniversary of the Year without a Summer, caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora in the Dutch East Indies the year before.

The extremely high levels of volanic material in the atmosphere led to darker skies which meant colder temperatures and failed harvests. Brown snow was reported in Hungary and red snow in Italy.

But the abnormalities in the sky were also responsible for the spectacular sunsets that inspired artists like Caspar David Friedrich and J M W Turner and the unceasing rain that provoked Mary Shelley to write Frankenstein and Lord Byron to write ‘Darkness’.

It’s no coincidence that, soon after this year of darkness, John Polidori published his book The Vampyre and the modern concept of this undead creature began to haunt the gothic imagination.

The Accession

c. 1911; Oil on canvas, 68 in. x 76.9 in.

A triumphant painting, but a last hurrah. The central figure is Sir Nevile Wilkinson, the last ever Ulster King of Arms & Principal Herald of Ireland, exercising the duties of his office by proclaiming the accession of the new king at Dublin Castle.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty and its legislative acts neglected to make provision for transferring this ancient office to the new Irish Free State, but Sir Nevile carried on regardless for nearly two decades, even issuing two dozen grants of arms on the day before his death in 1940.

After his death, the Oireachtas created the office of the Chief Herald of Ireland to continue the granting of arms, and in some sense the Chief Herald is a spiritual successor to the Ulster King of Arms.

Die Staatsrede

Staatspresident Jacobus Johannes Fouché giving the staatsrede from the throne of the Senate within the Houses of Parliament in Cape Town.

What is now the State of the Nation Address has its origins in the speech from the throne (in Afrikaans staatsrede meaning “state reasoning/rationale”) setting out the Government’s legislative programme for the year. The high point of the State Opening of Parliament, it was originally given by the Governor-General (or, in 1947, by the King of South Africa himself) but with the abolition of the monarchy in 1961 the sovereign’s vice-regal representative was abolished and replaced by the Staatspresident as chief officer of the South African state.

Giving a speech from an actual throne was considered too monarchic for a republican polity, so – like in the Boer republics of old – presidents gave their staatsredes standing. Here, State-President Fouché is flanked by the chiefs of the defence staff and police, the Serjeant-at-Arms with the mace, and the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod.

Of course, much of this was abolished in the 1980s with the constitutional innovations as a last-ditch attempt to entrench apartheid. South Africa is now on its third constitution since the above photo was taken.

It reminds me of how in Ireland almost all the traditions of the Viceroy (viz. the Viceregal Guard of Battleaxes, etc.) were abolished not by the Saorstát or Éire but by the British themselves – in their case by penny-pinching Victorians who found Dublin an easy target for cost-cutting.

The Rova of Antananarivo

The Rova of Antananarivo

The Tranovola (left) and Manjakamiadana (right) in the Rova of Antananarivo.

The Manjakamiadana (“Where It is Pleasant to Rule”) was the royal residence, later pretentiously clad in stone by Protestant missionaries, while the Tranovola (“Silver House”) was where the nefarious Rainivoninahitriniony received foreign diplomats after the nobles’ coup of 1863.

His complicity in the supposed regicide of that year — no one’s really quite sure what happened to Radama II — eventually led to his downfall two years later. His younger brother Rainilaiarivony proved a more skilful political operator, succeding Rainivoninahitriniony as prime minister and arranging his own marriage to the last three queens of the Merina kingdom of Madagascar.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories