History

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

A rood-stair pulpit

Among the features of the Church of All Saints in the Forest of Dean village of Staunton, Gloucestershire, is this fifteenth-century stone pulpit.

It is built into a rood-stair that once led to a wooden rood loft, demolished and removed some centuries ago.

This church also has a Norman font thought to have been hollowed out of an earlier square pagan Roman altar.

Articles of Note: 24.II.2021

• It is almost certain that we will never know who the actual winner of the 2020 presidential election was: the methods of fraud which might have been deployed are by their very nature ephemeral. Anton is right in that the best summary of the irregularities is from the U.S.-based Swedish academic Claes Ryn: How the 2020 Election Could Have Been Stolen. Ryn’s academic work is always an insightful read so his take here is worthwhile.

• I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: the Frenchman Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is always worth reading and always brings something to the table. P.E.G. argues the pre-Trumpers, anti-Trumpers, and never-Trumpers on the American centre-right need to recognise the reasons why Trump became a political phenomenon in the first place: Why Establishment Conservatives Still Miss the Point of Trump.

• One of the best books on urbanism in the Cusackian library is Allan Jacobs’s Great Streets. The expert work with its illustrative maps, diagrams, and line drawings is now a quarter-century old and on this anniversary Theo Mackey Pollack examines What Makes a Great Street.

• A new book argues that our vision of Northern Ireland as a corrupt and gerrymandered statelet from its birth in 1921 until the imposition of direct rule in 1972 is largely a myth. The editors Patrick J Roche and Brian Barton take to the pages of the once-great Irish Times to offer A Unionist History of Northern Ireland. It’s… an interesting perspective that will doubtless provoke a debate, but colour me sceptical.

Benedict of Palermo

The island of Sicily is a cross-section of the numerous kingdoms and empires which have ruled and inhabited it from the Phoenecians down to the present day. During the Norman conquest of the island — those Normans did get around — many Lombards came to help secure the Normans’ rule over the existing Sicilians who were mostly Greek and Arab. The Gallo-Italic dialect of those Lombards is still spoken in a few towns and villages speckled across the island and the settlements they founded are known as the Oppida Lombardorum.

In one such Lombard town, San Fratello, in the 1520s a son was born to an enslaved couple named Cristoforo and Diana whose piety was so highly regarded that their master granted this first-born son, Benedetto (Benedict), his freedom from birth.

From his earliest days Benedict was prone to solitude to the extent that he was mocked by his peers, in addition to being insulted frequently for his black skin. As a teenager he left the family home and became a shepherd but gave whatever he could to help the poor and those even less fortunate than him.

Discerning the call to solitude, Benedict entered the hermitage of Santa Domenica in Caronia but his reputation for holiness was such that the pious people of the island began to visit him and implore him for his prayers and miracles.

Accompanied by another member of the community, Benedict fled to other places around the island, offering great and severe penances in reparation for the sins of humanity, but no matter where he went within days the faithful had found out and pestered him.

When the founder of the hermetic community at Santa Domenica died, the brothers elected Benedict his successor, despite his lack of education and illiteracy. Benedict returned to lead the community until it was abolished in 1562 by the reforms of Pope Pius IV who urged independent groups of Francis-inspired hermits to regularise themselves into existing Franciscan orders.

Benedict went first to a Franciscan friary in Giuliana before settling into that of Santa Maria di Gesù in Palermo, the primary city of Sicily. Having been a superior of his old community, Benedict arrived at the Palermo community as a simple cook but even here his piety and talents were recognised. He was first put in charge of the novices and then, in 1578, his confrères elected him their custos or superior though he was only a brother rather than a priest.

He was known as a miracleworker across the island, but it was not only the poor, the sick, and the destitute who flocked to Benedict to seek his help. Theologians and men of learning came to visit this humble and uneducated friar. Even the viceroy of the island was known to take his counsel on important affairs of state.

In his later years, Benedict returned to being the cook of the friary until his death in April 1589. By that time the whole island of Sicily — Greeks, Arabs, Latins, all — revered this poor, humble, and unlettered friar.

Sicily’s ruler, King Philip III of Spain, ordered a magnificent tomb to be built to house Benedict’s remains in the friary of Santa Maria di Gesù, and in death his cult spread far beyond the island.

St Benedict of Palermo — or Benedict the Moor — was beatified by Benedict XIV in 1743 and canonised by Pius VII in 1807. Over the centuries, many non-white Christians came to implore his intercession and he became particularly popular among natives and mixed-race peoples in South America, in Africa itself, and amongst African-Americans in the United States.

This statue is believed to be the work of the Sevillian sculptor José Montes de Oca and was carved in the 1730s. Long in a private collection in Milan, since 2010 it has formed part of the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The Galloway Cross

What could be better than a hoard — and a Kircudbrightshire hoard at that? Sometime during the tenth century, a gentleman decided to deposit an interesting array of objects in Galloway only for them to be rediscovered by a metal detectorist in 2014.

Thus have come to us the Galloway Hoard, a collection of objects the most important of which is this pectoral cross made of silver and decorated with symbols of the four evangelists: the eagle of John, the ox of Luke, the angel of Matthew, and the lion of Mark.

As the hoard was buried when Kircudbrightshire was part of Northumbria — before the area became Scottish — the art has been identified as Anglo-Saxon from the age of the Vikings. My theory is an expert thief was at work, nicking precious objects from hapless victims — an armband gives the name of one poor Egbert in runes.

“The pectoral cross, with its subtle decoration of evangelist symbols and foliage, glittering gold and black inlays, and its delicately coiled chain, is an outstanding example of the Anglo-Saxon goldsmith’s art,” Dr Leslie Webster, an expert, said. “It was made in Northumbria in the later ninth century for a high-ranking cleric, as the distinctive form of the cross suggests.”

The Galloway Cross, before cleaning and conservation

All treasure found in Scotland must be reported to the Queen’s and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer who in 2017 determined the hoard’s value at £1.8 million. Scots law allows the discoverer to keep the full value of the hoard if there is no owner, though as it was found on glebelands belonging to the Church of Scotland that body’s General Trustees demanded a cut as well.

The objects themselves have found a home in the National Museum of Scotland who will be exhibiting them from February until May when they will go on tour to Aberdeen and Dundee.

Romes that Never Were

When the splendidly named Saint Sturm – Sturmi to his friends, apparently – founded the Benedictine monastery of Fulda in A.D. 742 we can presume he had no idea that the magnificent church eventually erected there (above) would one day be considered for housing the Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church.

Rome, caput mundi, is ubiquitously acknowledged by all Christian folk as the divinely ordained location for the Papacy, but this has not always been acknowledged in practice. Most memorable is the “Babylonian Captivity” of the fourteenth century when the papal court was based at the enclave of Avignon surrounded by the Kingdom of Arles. The illustrious St Catherine of Siena was influential in bringing that to an end.

Since the return from Avignon the Successor of Peter has prudently been keen to stay in Rome, but various crises over the past two centuries have seen His Holiness shifted about. General Buonaparte successively imprisoned Pius VI and Pius VII while he made to refashion Europe in his likeness, and the later slow-boil conquest of the Italian peninsula by the Kingdom of Sardinia caused much worrying in the courts of the continents as well.

In 1870, the Eternal City fell to the troops of General Cadorna, and while the Vatican itself was not violated it was widely assumed the papacy could not stay in Rome. Pope Pius IX evaluated several options, one of them seeking refuge from – of all people – the Prussian king and soon-to-be German emperor Wilhelm I.

Bismarck, no ally of the Church, but shrewd as ever, was in favour of it:

I have no objection to it — Cologne or Fulda. It would be passing strange, but after all not so inexplicable, and it would be very useful to us to be recognised by Catholics as what we really are, that is to say, the sole power now existing that is capable of protecting the head of their Church. …

But the King [Wilhelm I] will not consent. He is terribly afraid. He thinks all Prussia would be perverted and he himself would be obliged to become a Catholic. I told him, however, that if the Pope begged for asylum he could not refuse it. He would have to grant it as ruler of ten million Catholic subjects who would desire to see the head of their Church protected. …

Rumours have already been circulated on various occasions to the effect that the Pope intends to leave Rome. According to the latest of these the Council, which was adjourned in the summer, will be reopened at another place, some persons mentioning Malta and others Trent.

Bismarck mused to Moritz Busch what a comedy it would be to see the Pope and Cardinals migrate to Fulda, but also reported the King did not share his sense of humour on the subject. The advantages to Prussia were plain: the ultramontanes within their territories and throughout the German states would be tamed and their own (Catholic) Centre party would have to come on to the government’s side.

In the end, of course, the Pope decided to stay put in Rome and became the “Prisoner of the Vatican”, surrounded by an awkward usurper state that made attempts at friendship without betraying its hopes for legitimising its theft of the Papal States. It was the diplomatic coup of the Lateran Treaty in 1929 that finally allowed both states to breathe easy and created the State of the City of the Vatican, an entity distinct from but subservient to the Holy See of Rome.

The Second World War brought its own threats to the Pope’s sovereignty, and the wise and cautious Pius XII feared he might be imprisoned by Hitler just as his predecessor and namesake had been by Buonaparte. Pius was determined the Germans would not get their hands on the Pope and so signed an instrument of abdication effective the moment the Germans took him captive. He would have burnt his white clothing to emphasise that he was no longer the Bishop of Rome.

The record is not yet firmly established but it is rumoured that the College of Cardinals was to be convened in neutral Éire to elect a successor. One wonders where they would have met. The Irish government would undoubtedly have put something at their disposal — Dublin Castle perhaps? Despite the whirlwind of war, the election of a pope in St Patrick’s Hall would have warmed the cockles of many Irish hearts.

But what then? Ireland’s neutrality would have been useful but a German violation of the Vatican’s territory would have been grounds for open, though obviously not military, conflict. Further rumours, also totally unsubstantiated, had it that the King of Canada, George VI, quietly had plans drawn up for offering the Citadelle of Quebec to the Pope to function as a Vatican-in-Exile. Others claim it wasn’t until the 1950s that Quebec was investigated as a possibility by the Vatican in case Italy went communist, as was conceivable.

So Cologne, Fulda, Malta, Trent? None of these plans ever occurred, thank God.

And what about England? Why not? The court of St James and the Holy See, despite obvious and significant differences, enjoyed close relations and overlapping interests in many particular circumstances from the Napoleonic wars until present. Pius IX had put feelers out to Queen Victoria’s minister in Rome, Lord Odo Russell, in 1870 but the British ambassador more or less told him of course the Pope would be welcomed in England but don’t be silly, the Sardinians would never conquer Rome.

One imagines the British sovereign would grant a palace of sufficient grandeur to the exiled Pontiff. Hampton Court would do the job. It’s far enough from the centre of London but large enough to house a small court and the emergency-time administration of the Holy Roman Church. Would the ghost of Cardinal Wolsey plague the Princes of the Church?

Thanks be to God, we’ve never had cause to find out. At Rome sits the See Peter founded and so it looks to remain. Ubi Petrus, ibi ecclesia.

Wardour

The news from the West Country is that Jasper Conran OBE is selling up his place in Wiltshire, the principal apartment at Wardour Castle.

Wardour is one of the finest country houses in Britain, designed by James Paine with additions by Quarenghi of St Petersburg fame. It was built by the Arundells, a Cornish family of Norman origin, but after the death of the 16th and last Lord Arundell of Wardour the building was leased out and in 1961 became the home of Cranborne Chase School.

A friend who had the privilege of being educated there confirms that Conran’s assertion of Cranborne Chase being “a school akin to St Trinian’s” was correct, and tells wonderful stories of the girls’ misbehaviour.

Alas the modern world does not long suffer the existence of such pockets of resistance, and the school shut in 1990. The whole place was sold for under a million to a developer who turned it into a series of apartments, for the most part rather sensitively done, if a bit minimalist.

The real gem of Wardour, however, is the magnificent Catholic chapel which is owned by a separate trust and has been kept open as a place of worship. Richard Talbot (Lord Talbot of Malahide) chairs the trust and takes a keen interest in the chapel and the building. I was down there the Sunday the chapel re-opened for public worship after the lockdown and Richard was there making sure all was well.

Those interested in helping preserve this chapel for future generations can join the Friends of Wardour Chapel.

Onze Grootste President

The London Residence of President Martin van Buren

Transacting some business in March before the plague struck us here in London I found myself with a moment to spare and made a brief pilgrimage to No. 7, Stratford Place. It was in this handsome townhouse that Martin van Buren, the first New Yorker to ascend to the chief magistracy of the American Republic, had his residence when he served as the United States’s minister to Great Britain in 1831.

While I often claim that Calvin Coolidge was America’s greatest president in reality my chief devotion in that contest is to the Little Magician himself, the Red Fox of Kinderhook.

Among the many characteristics of this esteemed Knickerbocker is that English was not his native language and throughout his career as a democratically elected politician he spoke with a thick Dutch accent. To his wife, he spoke almost entirely in Dutch.

Jay Cost and Luke Thompson’s Constitutionally Speaking podcast at National Review recently released the first of a two episodes about van Buren and while I’m no fan of podcasts in general this was worth listening to.

One of the factors Cost and Thompson highlight is the utility of the party machine structures of the day in solidifying the practice of America’s democracy and acting as a vehicle of accountability, something too little appreciated by most later observers of the period.

We keen Kinderhookers and Van Buren Boys await the second instalment with anticipation.

Shamefully I have not yet made the pilgrimage to Kinderhook itself, but it’s pleasing to learn that the dominie of the Dutch Reformed Church is a graduate of the greatest university in the southern hemisphere.

How Our Ancestors Built

The Hudson River Day Line Building in Albany

The visitor arriving at Albany, the capital of the Empire State, might be forgiven for presuming the riparian French gothic mock-chateau he first views is the most important building in town.

Built as the headquarters of the Delaware & Hudson, a canal company founded in 1823 that successfully transitioned into the railways, the chateau now houses the administration of the State University of New York. (Indeed, the Chancellor once had a suitably grandiose apartment in the southern tower.) That building, with its pinnacle topped by Halve Maen weathervane, is worthy of examination in its own right.

But next to this towering edifice is an altogether smaller charming little holdout: the ticket office of the Hudson River Day Line.

In the nineteenth century the Hudson River Valley was often known as “America’s Rhineland” and travel up and down the river was not just for business but also for the aesthetic-spiritual searching that inspired the Hudson River School of painters.

The Day Line’s origins date to 1826 when its founder Abraham van Santvoord began work as an agent for the New York Steam Navigation Company. Van Santvoord’s company merged with others under his son Alfred’s guidance in 1879 to form the Day Line. (more…)

Buchan in Quebec

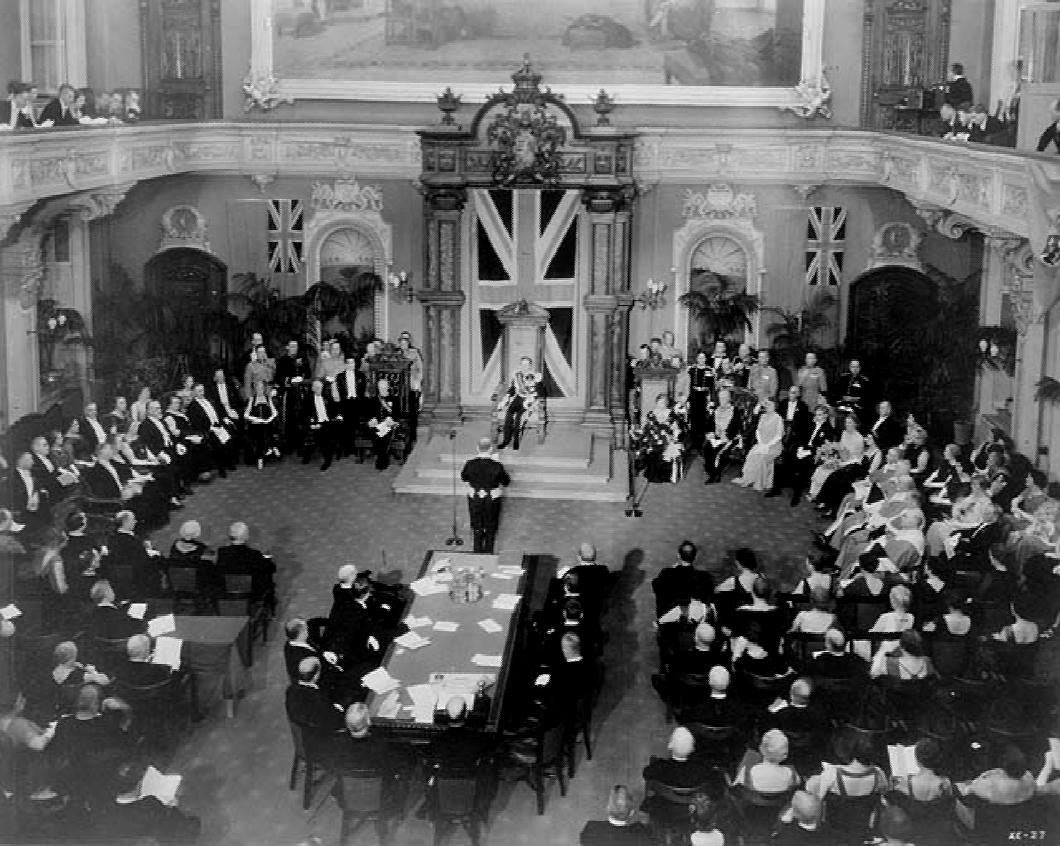

While the Salon bleu in Quebec’s parliament used to be green, the Salon rouge has kept its lordly colour. Conservative Quebec was the last of the Canadian provinces to abolish its unelected upper house which faced the chop in 1968, that year so beloved of duty-shirkers and ne’er-do-wells.

Thirty-three years earlier, the Salon rouge was the scene of a more regal ceremony: the official installation of the Scots writer and statesman John Buchan as Governor General of Canada. Being a Presbyterian with an in-built (but in his case only occasional) tendency to dourness, Buchan wanted to go as an ordinary commoner but the King of Canada insisted on a peerage for his viceregal representative in the dominion.

Thus it was Lord Tweedsmuir who arrived in Quebec in 1935 and was installed as Governor General in the Salon rouge on All Souls’ Day of that year. Above, the Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King gives an address after the swearing-in.

Buchan proved an influential Governor General and helped set the tone of Canada’s monarchy in the aftermath of the 1931 Statue of Westminster that recognised the distinct nature of the Commonwealth realms. He also orchestrated the King’s successful 1939 trip across Canada — which also featured the King and Queen holding court in the Salon rouge of Quebec’s Parliament.

By the time of his death in post in 1940, John Buchan had become His Excellency The Right Honourable The Lord Tweedsmuir GCMG GCVO CH PC. Not a bad end to a good innings.

Doom in Bloom

Such paintings were widespread in Catholic England where they served as a vital reminder to the faithful worshipping below of not just the torments of Hell but also the joys of Heaven. In the aftermath of the Protestant revolt, however, such vivid imagery was frowned upon, and the Salisbury Doom was painted over with limewash in 1593. Christ in Majesty was replaced by the royal arms of the usurper queen, Elizabeth I.

It was then forgotten about til its rediscovery in 1819 when hints of colour were discovered behind the royal arms. The limewash was removed, the remnants of the painting were revealed, recorded by a local artist, and then covered over yet again in white. Finally in 1881 the Doom was revealed to the world and subject to a Victorian attempt at restoration with mixed results.

Work on the church’s ceiling in the 1990s allowed experts to better examine the Doom which determined that, while there was a bit of fading, dirt was hanging loosely to the painting and it would be ripe for restoration. It has only been more recently, however, that money has been raised to restore the Doom.

There are other glories in this church yet to be restored, about which more information can be found on the parish’s website.

The Salisbury Doom before restoration (above) and after (below).

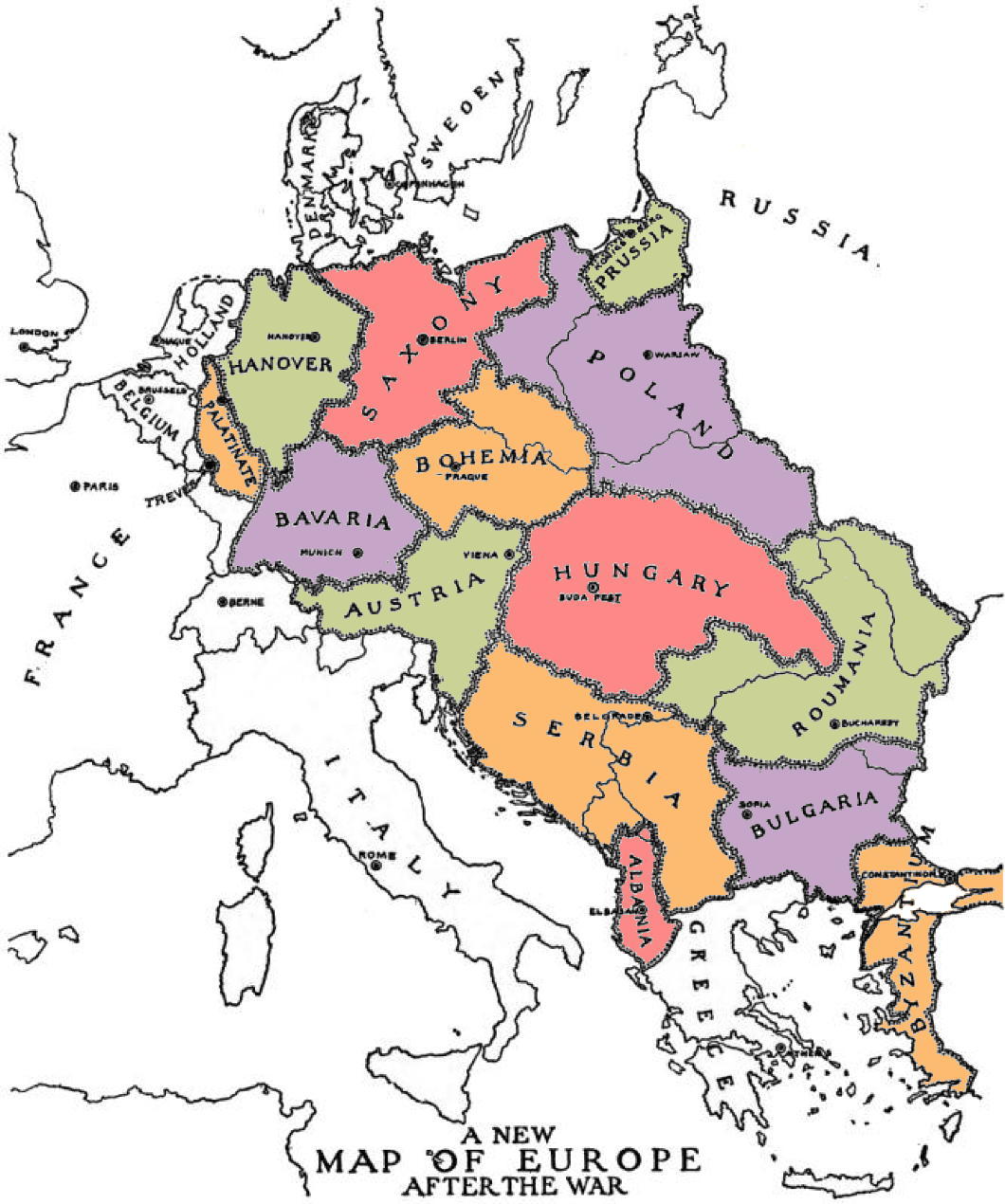

‘Solving’ Middle Europe

Ralph Adams Cram’s First-World-War Plan for Redrawing Borders

Ralph Adams Cram was not just one of the most influential American architects of the first half of the twentieth century: he was a rounded intellectual who expressed his thinking in fiction, essays, and books in addition to the buildings he designed.

Cram (and arguably even more his business partner Goodhue) had a gift for bringing the medieval to life in a way that was neither archaic nor anachronistic but instead conveyed the gothic (and other styles) as living, organic traditions into which it was perfectly legitimate for moderns to dwell, dabble, and imbibe.

His literary efforts include strange works of fiction admired by Lovecraft and political writings inviting America to become a monarchy. These have value, but it’s entirely justifiable that Cram is best known for his architectural contributions.

All the same, amidst the clamours of the First World War this architect of buildings played the architect of peoples and sketched out his idea of what Europe after the war — presuming the defeat of the Central Powers — would look like.

In A Plan for the Settlement of Middle Europe: Partition Without Annexation, Cram set out his model for the territorial redivision of central and eastern Europe “to anticipate an ending consonant with righteousness, and to consider what must be done… forever to prevent this sort of thing happening again”.

Cram, who provided a map as a general guide, predicted the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France, Schleswig-Holstein to Denmark, the Trentino and Trieste to Italy, much of Transylvania to Romania, Posen to a restored Poland, and Silesia divided in three.

Fundamental to the architect’s thinking was that “neither Germany, Austria-Hungary, nor Turkey can be permitted to exist as integral or even potential empires”. Austria and Hungary would be split and Germany needed to be partitioned (not, as some later plans had it, annexed). (more…)

Lady Day

Today is Lady Day, the Feast of the Annunciation when the Archangel Gabriel appeared to the Blessed Virgin Mary and announced that she would conceive and bear the child Jesus.

The angelic salutation – “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee… Blessed art thou amongst women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus” – forms the basis of the Ave Maria, one of the most widely uttered prayers in Christendom.

Traditionally this has been one of the greatest of devotions to the Virgin amongst the English, which is why there are so many pubs across England named ‘The Salutation’.

For centuries in England and Scotland (as well as elsewhere), Lady Day was the first day of the calendar year. Scotland moved this to 1 January in 1600 and England did likewise in 1750.

Nonetheless, the English tax year is still based on this date as it commences on 6 April, which is the Annunciation plus twelve days to mark the difference between the old Julian calendar and the modern Gregorian one.

In the realms of fiction, 25 March is the day Tolkien chose for when Frodo destroyed the Ring in Mount Doom, securing the fall of Sauron – with obvious parallels to Christ’s Incarnation securing the defeat of Satan.

This stained glass roundel above is not English, however, but from the Southern Netherlands around 1500-1510.

Elsewhere, A Clerk of Oxford has a good section on the Annunciation.

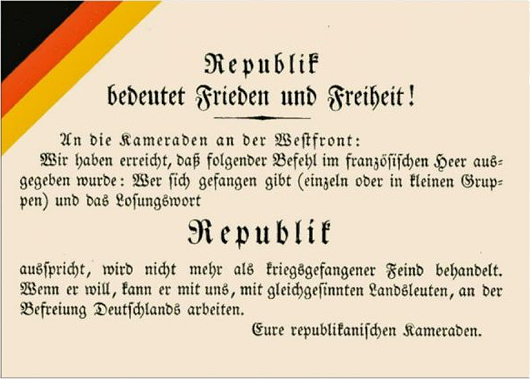

Weimar’s Black, Red, and Gold

In fact, there was a great deal of overlap between these two sides, and in the most recent Junge Freiheit Dr Karlheinz Weißmann explains how the troubled Weimar Republic made its choice of national symbols.

The colours of the Republic

by Karlheinz Weißmann — Junge Freiheit 18 February 2019

(slapdash unofficial totally unauthorised translation)

At the end of December 1918, Harry Graf Kessler noted confusedly in his diary that supporters of the [liberal republican] German Democratic Party (DDP) had marched through the centre of Berlin, with the “Greater German colours” black-red-gold and singing Der Wacht am Rhein.

In fact, the left-wing liberals were the only political group next to the Völkisch movement who had clung on to the black-red-gold. For both of them, it was about the ideal of an all-German state, including the Austrians. For the Liberals, it also represented the ideals of the revolution of 1848, while for the Völkisch there was the idea that black, red, and gold were the ancient Aryan colours.

During the period of downfall in 1918 it wasn’t the black-red-gold that mattered: it was the red of the socialists. Majority and Independent Social Democrats as well as the Communists all used it as a symbol. Red armbands, red cockades, and red flags marked the followers of the new republic, whose socialist underpinning was generally believed.

Black-red-gold as last option

By contrast, the old imperial colours of black-white-red almost disappeared. Significantly, the naval mutineers in Kiel had barely raised a hand to defend them. But the soldiers returning home from the front marched under black-white-red flags — which they had made themselves — and were received in the cities, even in Berlin, with black-white-red flags and decorations. The newly established Freikorps also deployed the old imperial colours, as did the cockade of the new Reichswehr whose ranks included many opposed to the republican order.

With this juxtaposition of revolutionary red and the black-white-red of tradition, black-red-gold — Schwarz-Rot-Gold — came as the last option. Some hoped that, on the one hand it would stand for moderation and against total upheaval, while on the other hand it suggested that defeat in the war did not spell the final downfall of the nation.

On 9 November 1918 an organ of the far right, the Alldeutschen Blätter, published an essay entitled “Black-Red-Gold”:

“The birth of Greater Germany is approaching! … Cheer the old black-red-golden colours! Decorate like Vienna your houses with the black-red-golden flags, bows, and bands and show all the world from Aachen and Königsberg to Bozen [Bolzano], Klagenfurt, and Laibach [Ljubljana] that we are a united people of brothers, in no distress of separation or peril.”

Symbol of treason

The 18 February 1919 decision of the State Committee of the Republic to adopt black-red-gold as provisional colours of the Reich was still supported by the expectation that a Greater German Republic would emerge. But the “Anschluss” of Austria was banned at the instigation of the victorious powers and in flagrant contradiction to the right of the self-determination of peoples. This resulted in the first serious discrediting of the black-red-gold.

The second was that black, red, and gold had been reputed to be a symbol of treason since the beginning of the war. A group of deserters and pacifists calling themselves the “Friends of the German Republic” — financed with French money and operating from Switzerland — used the colours for their cause as early as 1915, and as early as the spring of 1918 Entente aircraft distributed calls for desertion and revolution along the western front, marked with a black-red-gold stripe or border.

Almost certainly the majority of the population was relieved when, on instructions from the national government, the workers’ and soldiers’ councils adopted the black-red-gold [replacing the red of revolution] but passive acceptance was not enough to give the colour combination permanent support. This was particularly evident in the peculiar “flag compromise” presented by the government with the support of Majority Social Democrats, the Center Party, and part of the DDP during the deliberations of the National Assembly.

According to this compromise, the black-red-gold was introduced as the national flag, while the merchant ensign was the old black, white, and red — albeit with a small black-red-gold flag infelicitously shoved in the canton. Interior Minister Eduard David’s rationale for the choice — that the old colours had been “party” rather than “national” colours — simply did not correspond to fact.

Symbol of Greater Germany

Closer to the truth was the justification that black, red, and gold were the symbols of a Greater Germany. Interior Minister David said:

“What dynastic Germany could not do, democracy must succeed in doing: achieving moral conquests beyond the frontier and, above all, among those who by blood and language belong to us. To win the Greater German unity must now be our goal, not through war and violence, but through the recruiting power of the new republican Germany, and let us fly forward in front of the black-and-red-gold banner!”

In any case, Article 3 of the Weimar Constitution, which entered into force on 11 August 1919, was far from providing a sound answer to the flag question of the young state. As constiutional scholar Ernst-Rudolf Huber wrote:

“This Weimar flag compromise became the cause of endless strife. If the constitutional function of state colours exists in their symbolic power to integrate the state’s unity, the state-sanctioned dualism of contrasting colours manifested in the Weimar flag compromise is a permanent element of disintegration. The flag compromise, with its juxtaposition of the old and new colours, did not diminish the problem of the colour change but rather aggravate it.”

Claudia McNeil

As a black Jewish Catholic, Claudia McNeil was pretty much everything the Ku Klux Klan hated. She was born to a black father and a part-Apache mother in Baltimore, Maryland but in her teenage years was adopted by a Jewish family in New York who instructed her in Judaism and taught her fluent Yiddish.

She married aged 19 but lost her husband in the Second World War and both her sons in the Korean War.

After training as a librarian, McNeil drifted into vaudeville theatre and nightclubs, eventually making her Broadway debut in 1953 as Tituba in The Crucible.

“The Jewish faith left an indelible stamp on her spirit,” Ebony magazine reported in 1960, “but she became a convert to Catholicism in 1952.” McNeil often reported that she stopped to pray before every evening’s performance.

Her most famous role was as the matriarch in A Raisin in the Sun in 1959, reprised in the 1961 film in both of which Sidney Poitier also starred.

Deeply appreciative of the gifts God gave her, McNeil was known never to turn down a chance to appear at charity benefit performances, especially for the NAACP and the American Jewish Congress.

Despite the losses she suffered in her life Claudia McNeil insisted “I have everything I’ve ever wanted from life.”

“I have more work than I can do. I have a nice, cheerful, comfortable home. I am solvent. Above all, I have strength, health, and peace of mind. I know where I’m going. I am an American citizen. I love my country. I pay my taxes and vote, and I intend to have a say in how my country is run.”

McNeil retired in 1983 and died ten years later.

Secret Splendor

by Andrew Cusack (Weekly Standard, 13 September 2010)

Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic

by Xander van Eck

Waanders, 368 pp., $100

This book is the first major overview and exploration of the art of the clandestine Roman Catholic churches in the Netherlands. It is not a study of paintings so much as a history in which art is like the evidence in a detective story, or perhaps even the characters in a play. It might seem extraordinary that there was a place for large-scale Catholic art during the Dutch Republic: Pre-Reformation churches had been confiscated and were being used for Calvinist services, while priests offered the Mass secretly in makeshift accommodations. Eventually a bargain between Dutch Catholics and the civil authorities emerged, trading Catholic nonprovocation in exchange for private toleration of the practice of the faith. Catholics began to purchase properties which, for all outward appearances, maintained the look of ordinary residences but whose interiors were transformed into resplendent chapels and churches.

Xander van Eck provides verbal portraits (often accompanied by contemporaneous painted ones) of several of the important clerics of the Dutch church during this period: Sasbout Vosmeer, the Delft priest influenced by St. Charles Borromeo; Philippus Rovenus, the vicar-apostolic who placed greater emphasis on clandestine parishes having specially dedicated churches, even while they kept an outward unecclesiastical appearance; and Leonardus Marius, the priest who promoted devotion to the 14th-century Eucharistic “Miracle of Amsterdam.” Marius was of such prominence that, after his death, shopkeepers rented out places on their awnings for punters to view his funeral procession. Van Eck includes a handful of amusing asides, such as the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Netherlands as a result of their constant discord with the secular clergy. Mass continued to be offered at the Jesuit church of De Krijtberg in Amsterdam “in the profoundest secrecy” — thus creating a clandestine church within a clandestine church!

The role of the clergy in sustaining the Dutch Church is unsurprising, but it is instructive to learn how instrumental laity were to keeping alive the light of Catholic faith in the Netherlands at the time. Clandestine churches relied on the generosity of Catholic families. Prominent families often provided their own kin as consecrated virgins who brought large dowries into the church, or as priests with suitable inheritances to maintain or endow clandestine parishes. The clandestine church of ’t Hart in Amsterdam, built by the merchant Jan Hartman for his son studying for the priesthood, is still open today as the Amstelkring Museum and Chapel of “Our Lord in the Attic.”

While van Eck explores the extent to which Dutch art from the period followed European norms, an emphasis on the particularity of the art of the clandestine church is to be expected. The sheer volume of art produced during this period — for just three Amsterdam churches alone there were 16 altarpieces — is partly explained by the phenomenon of “rotating altarpieces.” The paintings above the altar would be changed according to the feast or season — a practice sometimes seen in Flanders or parts of Germany but never nearly so widespread as in the Netherlands proper.

Constrained as clandestine churches were on the narrow plots typical of Dutch cities, there was no room for side chapels that might include the large funerary monuments prominent families would construct. This left altarpieces as the most convenient way for munificent Catholics to provide art for their churches: Rotating the altarpieces provided a handy way of displaying numerous commissions rather than just the donation of whoever had been generous most recently, and the themes of these commissions tended to vary in appropriateness to different feasts and seasons.

Some found fault with this method: Jean-Baptiste Descamps, visiting Antwerp in 1769, complained that the most interesting altarpieces were not permanently displayed and were more likely to be damaged in the process of being moved so often.

While the accomplishment and ingenuity of Dutch Catholics in keeping their faith during the Republic was striking, the ill-defined administrative structure of the persecuted church allowed conflicts between clerics to thrive, and doctrinal disputes emerged and festered. The disputes over Jansenism that swept over France and the Netherlands, for example, only exacerbated the administrative problems of the clandestine church. Like their Calvinist compatriots, the Jansenists tended to frown on indulgences, the veneration of saints, recital of the rosary, and private acts of worship, putting greater emphasis on the Scriptures and a more rigorous asceticism. As van Eck points out, this difference in emphasis was not exclusive to the Jansenists, but their novelty (and their heresy) was in preaching the exclusivity of their approach above all others.

Numerous vicars-apostolic had written to Rome arguing for the re-establishment of the episcopacy in the Netherlands to solve the disputes over authority, but their appeals fell on deaf ears. In 1723 a large portion of the Jansenist clergy reinstituted the episcopacy by electing an archbishop of Utrecht from their number — and were subsequently excommunicated, splitting the clandestine church and its clergy in two. (This excommunicated rump united with the opponents of papal infallibility in the following century to form a body that still calls itself the Old Catholic Church.)

When one looks at all this glorious art, not to mention the lives and pious ingenuity of the persecuted, it’s difficult not to feel a little poorer, considering the fruits of our churches in an ostensibly free era. Why does the church today commission painters who are either mediocre or trendy — or both? Artists like Hans Laagland and Leonard Porter show that good art — good liturgical art, even — is possible today, but commissions from the church for traditional artists are sadly few.

Roots and Permanent Interests

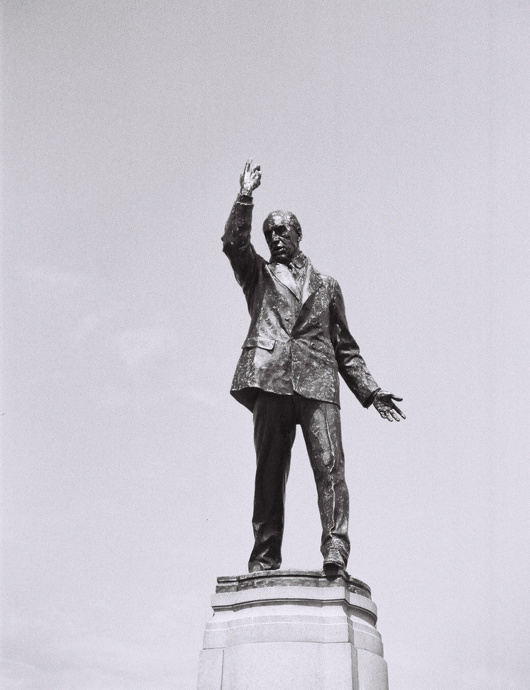

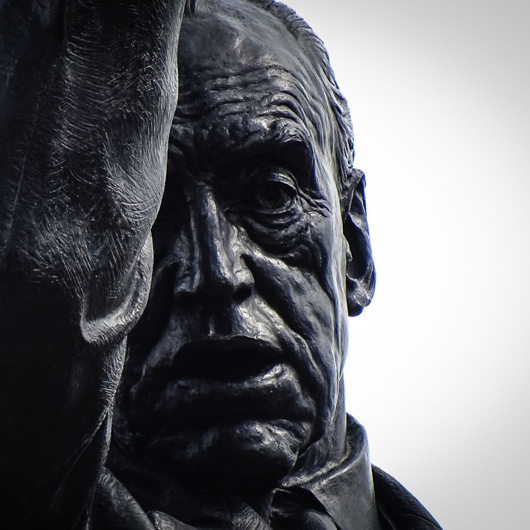

Carson at Stormont

Few statues in Ireland are as dramatic as that of Edward Carson at Stormont. The unionist leader is depicted in amidst an oratorical flourish, doubtless in one of his speeches to mass meetings condemning home rule.

In the 1910s as the rebirth of an Irish parliament looked more likely, Carson took up the cause of fighting home rule on behalf of Ireland’s large Protestant minority who feared Catholic domination. When the anti-home rulers realised the cause was losing, they retreated from Irish unionism to Ulster unionism. If home rule was to be granted, Ulster must be exempted. In the end this meant home rule was granted to a parliament covering two-thirds of the Irish province of Ulster — six counties that would henceforth be known as Northern Ireland.

“His larger than life-size statue,” one historian wrote, “erected in his own lifetime in front of the Northern Ireland parliament at Stormont, symbolizes the widely held perception that Northern Ireland is Carson’s creation.”

This is of course the great irony, given that Edward Carson was a Dublin boy through and through. While instrumental in ensuring northeastern Ireland’s exemption from an Irish parliament, Carson actually had little to do with the entity thereby created. When offered the premiership of Northern Ireland he declined it on the grounds of having no real connection with the place.

Craig, not Carson, is the true father of Northern Ireland; he imbued the new statelet with a sense of bigotry and tribal hatred that Carson lacked. The Dubliner urged Ulster’s new leaders to treat the province’s Catholics well.

“We used to say that we could not trust an Irish parliament in Dublin to do justice to the Protestant minority,” Carson said. “Let us take care that that reproach can no longer be made against your parliament, and from the outset let them see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from a Protestant majority.”

Alas, it became apparent to Carson that discrimination and inequality were becoming in-built within Northern Ireland’s government, from the Parliament at Stormont down to the lowest forms of local government. He confided to a Catholic friend in London that rather than being an integral part of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland was turning into “a second-class dominion”.

After partition Carson was created a British judge and accordingly ennobled. (Disappointingly the plaque on his Dublin birthplace next to Conradh na Gaeilge refers to him by the incorrect style of ‘Lord Edward Carson’.) He settled at Clever Court near Minster-in-Thanet, Kent, and never lived in his native Ireland again.

Nonetheless he was held in awe and reverence by the Protestant Unionists of Ulster, who commissioned the striking statue by Leonard Stanford Merrifield that stands in front of Parliament Buildings, Stormont — now home to the Northern Ireland Assembly. It was unveiled by Craig, by then ennobled as Lord Craigavon, while Carson was alive and present in July 1932, joined by a crowd of 40,000 well-wishers.

Carson died in 1935 and was given the rare honour of a state funeral. HMS Broke brought his Union-Jack-draped coffin back to Ireland — albeit to Belfast — and he was interred in the Anglican Cathedral of St Anne. Northern Ireland claimed him even in his final burial: soil from each of its six counties was scattered on his coffin when laid to rest in the tomb.

Still his statue stands at Stormont, gesturing stridently as if to challenge an entire province — a province he by his own description had little to do with. Calls for it to be removed emanate occasionally from typically boring quarters and have so far been rebuffed — wisely. Carson, unlike many of those who cherished his memory, was an honourable man, and it is a pity it took so long for the Protestants of Ulster to heed the advice of their confrère from Dublin.

Knickerbocker Spires

Before the age of the skyscrapers, New York’s church spires dominated the horizon and dwarfed their neighbours just like in the medieval towns and cities of the old world — as this photo from the 1900s shows.

Here St Patrick’s Cathedral holds court, with the St. Nicholas Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church poking up a few blocks down Fifth Avenue.

Slightly north on that same boulevard sits the grand renaissance palazzo of the University Club, with the spire of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church poking up behind it.

Hollandic Fever

Adapted from the Deborah Moggach novel of the same name, ‘Tulip Fever’ is a curious concoction. Some of the plot holes are so big you could drive a coach and horses through them. For example, how is it that – in Calvinist-controlled seventeenth-century Amsterdam – there is a massive Catholic convent perfectly accepted by everyone and operating as if nothing is out of place? It’s the size of Norwich Cathedral! (In fact, it is Norwich Cathedral – this entire production was filmed in Great Britain.)

The often excellent Chrisoph Waltz is curiously mismatched with his role here: a little bit too much of a parody of the proud, pious Amsterdam merchant in the start, which makes his eventual transformation a little unconvincing. The plot also shows little of the brilliance of its co-writer Sir Tom Stoppard. (In fact, there’s a bit too much plot.) At least Dame Judi Dench is effortless in her role as the unnamed Abbess of St Ursula. Tom Hollander is thrown in for a laugh, in a role suited to his abilities.

For curiosity’s sake the most interesting casting choice was Joanna Scanlan, known as the useless press officer at DOSAC in ‘The Thick of It’. Here she is the dressmaker Mrs Overvalt, but she was Vermeer’s cook Tanneke in ‘Girl with the Pearl Earring’. If my rudimentary calculations are correct, this means she has been in two-thirds of twenty-first-century films set in the Dutch seventeenth century.

It is, however, a beautifully shot production, for which I suspect we have the cinematographer Eigil Bryld to thank. (He’s worked on one seventeenth-century film before, and on another set in the Low Countries.) Bookended by scenes of Friedrichian romanticism (I’m into that) the film encourages me in my deeply felt belief that we need to revive seventeenth-century Dutch domestic architecture as a style.

Observations

All those interested in the history of the workers’ struggle would have enjoyed a letter to the editor printed in last week’s Observer.

Floreat Etona, left and right

Alex Renton is correct when he points out that the 20 old Etonian MPs currently sitting are all Tories, but this is far from usually the case (“Our educational apartheid laid bare”, Books, New Review). The first OE to be elected a Labour MP was in 1923, and the party consistently had OE representation on its benches from then all the way to 2010. Even Clement Attlee’s transformative postwar Labour government included two old Etonians: Hugh Dalton as chancellor of the exchequer and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence as India secretary.

Andrew Cusack (Conservative, non-OE)

London SE1

Of course, no one actually reads the Observer, so it went entirely unnoticed.

I have acquired a dangerously successful rate of my pedantic missives being printed in periodicals. The editors of the Irish Times, Times Literary Supplement, Catholic Herald, and even the Tablet have all been guilty of lapses in judgement in this regard.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories