Germany

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

‘The man who walked’

The Daily Telegraph — 6 September 2008

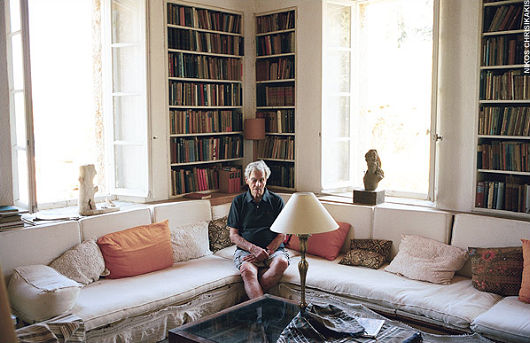

At 18 he left home to walk the length of Europe; at 25, as an SOE agent, he kidnapped the German commander of Crete; now at 93, Patrick Leigh Fermor, arguably the greatest living travel writer, is publishing the nearest he may come to an autobiography – and finally learning to type. William Dalrymple meets him at home in Greece

‘You’ve got to bellow a bit,’ Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor said, inclining his face in my direction, and cupping his ear. ‘He’s become an economist? Well, thank God for that. I thought you said he’d become a Communist.’

He took a swig of retsina and returned to his lemon chicken.

‘I’m deaf,’ he continued. ‘That’s the awful truth. That’s why I’m leaning towards you in this rather eerie fashion. I do have a hearing aid, but when I go swimming I always forget about it until I’m two strokes out, and then it starts singing at me. I get out and suck it, and with luck all is well. But both of them have gone now, and that’s one reason why I am off to London next week. Glasses, too. Running out of those very quickly. Occasionally, the one that is lost is found, but their numbers slowly diminish…’

He trailed off. ‘The amount that can go wrong at this age – you’ve no idea. This year I’ve acquired something called tunnel vision. Very odd, and sometimes quite interesting. When I look at someone I can see four eyes, one of them huge and stuck to the side of the mouth. Everyone starts looking a bit like a Picasso painting.’

He paused and considered for a moment, as if confronted by the condition for the first time. ‘And, to be honest, my memory is not in very good shape either. Anything like a date or a proper name just takes wing, and quite often never comes back. Winston Churchill – couldn’t remember his name last week.

‘Even swimming is a bit of a trial now,’ he continued, ‘thanks to this bloody clock thing they’ve put in me – what d’they call it? A pacemaker. It doesn’t mind the swimming. But it doesn’t like the steps on the way down. Terrific nuisance.’

We were sitting eating supper in the moonlight in the arcaded L-shaped cloister that forms the core of Leigh Fermor’s beautiful house in Mani in southern Greece. Since the death of his beloved wife Joan in 2003, Leigh Fermor, known to everyone as Leigh Fermor, has lived here alone in his own Elysium with only an ever-growing clowder of darting, mewing, paw-licking cats for company. He is cooked for and looked after by his housekeeper, Elpida, the daughter of the inn-keeper who was his original landlord when he came to Mani for the first time in 1962.

It is the most perfect writer’s house imaginable, designed and partially built by Leigh Fermor himself in an old olive grove overlooking a secluded Mediterranean bay. It is easy to see why, despite growing visibly frailer, he would never want to leave. Buttressed by the old retaining walls of the olive terraces, the whitewashed rooms are cool and airy and lined with books; old copies of the Times Literary Supplement and the New York Review of Books lie scattered around on tables between Attic vases, Indian sculptures and bottles of local ouzo.

A study filled with reference books and old photographs lies across a shady courtyard. There are cicadas grinding in the cypresses, and a wonderful view of the peaks of the Taygetus falling down to the blue waters of the Aegean, which are so clear it is said that in some places you can still see the wrecks of Ottoman galleys lying on the seabed far below.

There is a warm smell of wild rosemary and cypress resin in the air; and from below comes the crash of the sea on the pebbles of the foreshore. Yet there is something unmistakably melancholy in the air: a great traveller even partially immobilised is as sad a sight as an artist with failing vision or a composer grown hard of hearing.

I had driven down from Athens that morning, through slopes of olives charred and blackened by last year’s forest fires. I arrived at Kardamyli late in the evening. Although the area is now almost metropolitan in feel compared to what it was when Leigh Fermor moved here in the 1960s (at that time he had to move the honey-coloured Taygetus stone for his house to its site by mule as there was no road) it still feels wonderfully remote and almost untouched by the modern world.

When Leigh Fermor first arrived in Mani in 1962 he was known principally as a dashing commando. At the age of 25, as a young agent of Special Operations Executive (SOE), he had kidnapped the German commander in Crete, General Kreipe, and returned home to a Distinguished Service Order and movie version of his exploits, Ill Met by Moonlight (1957) with Dirk Bogarde playing him as a handsome black-shirted guerrilla.

It was in this house that Leigh Fermor made the startling transformation – unique in his generation – from war hero to literary genius. To meet, Leigh Fermor may still have the speech patterns and formal manners of a British officer of a previous generation; but on the page he is a soaring prose virtuoso with hardly a single living equal.

It was here in the isolation and beauty of Kardamyli that Leigh Fermor developed his sublime prose style, and here that he wrote most of the books that have made him widely regarded as the world’s greatest travel writer, as well as arguably our finest living prose-poet. While his densely literary and cadent prose style is beyond imitation, his books have become sacred texts for several generations of British writers of non-fiction, including Bruce Chatwin, Colin Thubron, Philip Marsden, Nicholas Crane and Rory Stewart, all of whom have been inspired by the persona he created of the bookish wanderer: the footloose scholar in the wilds, scrambling through remote mountains, a knapsack full of books on his shoulder.

Germany carved amongst her neighbours

What is this cartographic madness? Hanover part of the Netherlands? Kassel ruled by France? Nuremburg part of a Bohemia that reaches to the Frankfurt suburbs? Hamburg in Denmark? Regensburg on the Austro-Czech border? I came across the company Kalimedia in an article from Die Zeit a month or two ago and discovered their map of a Europe without a Germany. Believe it or not, there were plans of one sort or another to achieve similar results at the end of the Second World War. The major plan for the dissection of Germany was merely a creation of Nazi propaganda, and while the vaguely similar Morgenthau Plan did exist, it was soon shelved once its impracticality became obvious.

The Bakker-Schut Plan, meanwhile, was a Dutch proposal for the annexation of several German towns, and perhaps even a number of German cities. German natives would be expelled, except for those who spoke the Low Franconian dialect, who would be forcibly dutchified. They even came up with a list of new Dutch names for German cities: c.f. the post at Strange Maps on “Eastland, Our Land: Dutch Dreams of Expansion at Germany’s Expense”.

Le monde diplomatique

The German edition of Le monde diplomatique underwent a complete overhaul not too long ago. Unlike the main French edition of Le monde diplo, which exhibits the exact style of a French newspaper of mediocre design circa 1996, the German edition now exudes a certain calm and composed modernity. The redesign is the work of the German typographer and designer Erik Spiekermann, whom the Royal Society have named a Royal Designer for Industry (entitling him to an HonRDI after his name; only “hon” because he is not a British subject). Mr. Spiekermann was responsible for the much-lauded redesign of The Economist, the magazine you read when the airport lounge doesn’t have a copy of The Spectator.

Amidst pickelhaubes resplendent

The Chancellor of Germany is seen here worriedly admiring the pickelhaubed cavalry on her state visit to Colombia. Such elements of tradition, widespread in South America, are unofficially but totally banned in Germany.

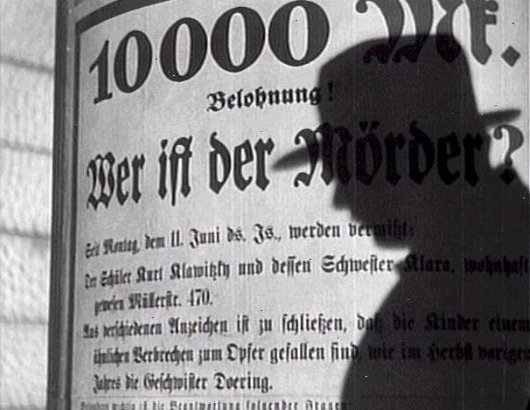

«Metropolis» rediscovered

Fritz Lang’s «Metropolis» was one of the most groundbreaking films of the silent era, and so the news that scenes previously lost have been rediscovered is most welcome. While «Metropolis» is one of those films that is perhaps best appreciated if only viewed once, I certainly look forward to a restored version being released in the next few years.

Still, my favorite of Fritz Lang’s works remains the classic «M», a sound film released in 1931, a few years into the talkie era. Peter Lorre is at his best in the starring role, and of course with Lang at the helm, «M» is expertly shot. Those whistled notes from Peer Gynt are never the same again after seeing this film!

How a newspaper should look

The Sunday edition of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung has always been a handsome newspaper. I admired its appearance so much that it provided much of the inspiration for the look of the Mitre during my editorship of that august publication. The weekday FAZ was famously reactionary in forbidding the appearance of photographs or any colour on the front page, so the Sonntagszeitung was viewed as an opportunity to be a bit more colourful and a little more free, but still within a solid traditional design.

It saddened me to learn that the Monday-through-Thursday FAZ has given in to the Spirit of the Age and now allows not only colour on its front page but photographs there as well. It now looks like a fairly conventional German newspaper, rather than the king of German dailies.

I will miss the old black-and-white FAZ because for me it brings back memories of visits to Dr. Timmerman‘s flat in St Andrews. Sofie and I used to go over to the good professor’s place for German pancakes on Shrove Tuesday (or to listen to his giant old radio, or to simply enjoy good conversation with good wine) and he had a massive pile of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitungs which I believe he only discarded at the end of the month.

Because the Frankfurter Allgemeine‘s front page is now a little less boring, the world in general is now a little less interesting.

‘Flying High’

[I came across this piece by Taki whilst trawling through the Cusack archives, and I thought now would be the appropriate time to share it.]

By Taki Theodoracopulos (The Spectator, 22 April 2006)

Do any of you remember a film called The Blue Max? It is about a German flying squadron during the first world war. A working-class German soldier manages to escape trench warfare by joining up with lots of aristocratic Prussian flyers who see jousting in the sky as a form of sport, rather than combat. Eager for fame and glory — 20 confirmed kills earns one the ‘Blue Max’, the highest decoration the Fatherland can bestow — the prole shoots down a defenceless British pilot whose gunner is dead. His squadron leader is appalled. ‘This is not warfare,’ he tells the arriviste. ‘It’s murder.’

I know it’s only a film, and a Hollywood one at that, but jousting in the air was a chivalric endeavour back then, with pilots who crash-landed behind enemy lines being treated as honoured guests before being interned for the duration. The man who embodied all the chivalric virtues was, of course, Manfred von Richthofen, whose family had been ennobled by Frederick the Great in the 1740s. When Baron Richthofen became a fighter pilot in the late summer of 1916, it was still only 13 years since the first flight of Orville Wright. The technique of applying air power to warfare was barely understood. One looped-the-loop, and pilots who managed to shoot down enemy aircraft and survive were regarded as heroes and quickly accumulated chestfuls of medals. When the Red Baron (his plane was painted a dark red, hence the nickname) died on 21 April 1918, the Times for 23 April devoted one third of a column to England’s fallen enemy, remarking that ‘all our airmen concede that Richthofen was a great pilot and a fine fighting man’.

By the time of his death, the Red Baron had notched up 80 victories, a record, with the leading French ace, René Fonck, claiming to have shot down 157 German aircraft, but only 75 being confirmed. (Rather French, that.) Needless to say, the mystery surrounding Richthofen’s death added to his legend. No one knows for sure who shot him down, or even if the bullet which killed him came from the ground. The English who found his body treated it with all the ceremony they would have accorded one of their own. An honour guard escorted the corpse to his own lines and British pilots overflew and dipped their wings. Those were the days. Out of 8 million men of his generation who died in that useless war, Richthofen’s is among the few names which will most likely be remembered by the general public on the 200th anniversary of his death.

His brother Lothar and his cousin Wolfram (who bombed Stalingrad 25 years later, and was one of Hitler’s favourites) flew alongside the baron, establishing a tradition for excellence and gallantry in the Luftwaffe. The second world war saw great heroics by German pilots, starting with Hans Ulrich Rudel, with something like 400 Stalin tanks to his credit, Adolf Galland, Erich Hartmann, who shot down 352 Soviet aircraft in the course of 1,500 missions, and Walter Novotny, with 250 Soviet aircraft in fewer than 450 missions.

My favourite is, of course, Prince Heinrich Sayn-Wittgenstein, whose heroics overshadowed the rest, and whose plane was shot down at the very, very end of the war in Schonhausen, the Bismarck home. Wittgenstein had his crew bail out first but was unconscious when he hit the ground. He had been hit while in the cockpit. By the end of the war he had become such an ace and legend he could do what he pleased. He once flew a combat mission with a raincoat over his dinner jacket. A few days before he had been to Hitler’s headquarters to receive the Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross. He told the beautiful Missie Vassiltchikov on the telephone, ‘Ich war bei unserem Liebling’ (I have been to see our darling) and added how surprised he was his handgun had not been removed before he entered ‘the Presence’. Heinrich would have loved to have bumped him off, but by then Germany was ruined and the prince died three days later. Hitler had many heroic pilots grounded towards the end, but Wittgenstein, being noble, was kept flying.

Why am I bringing all this up in the year of Our Lord 2006? As I told you last week, while down in Palm Beach, a friend of mine, Richard Johnson, tied the knot with Sessa von Richthofen, and I flew down a group of friends for three days of non-stop celebrations. The couple exchanged vows on an 80-year-old river boat which plies its trade in the inland waterway which crisscrosses Florida. My speech went down great, but then some ghastly paparazzo by the name of Harry Benson went around complaining about it. Never to me, needless to say, otherwise one more kill would have been added to the Richthofen legend.

“Der Rote Baron”

Foreign Film Fictively Frames Favorite Fabled Freiherr

Our cunning cousin, the Hun, has cleverly concealed a card up his hunting-jacket sleeve. Just when you thought the continual winging by hand-wringing Germans about their militarist past (or at least the thoroughly shameful parts thereof) would never end, a new film depicts the life of the dashing Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen: better known to us as The Red Baron.

Our cunning cousin, the Hun, has cleverly concealed a card up his hunting-jacket sleeve. Just when you thought the continual winging by hand-wringing Germans about their militarist past (or at least the thoroughly shameful parts thereof) would never end, a new film depicts the life of the dashing Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen: better known to us as The Red Baron.

“Der Rote Baron” is showing in den deutschen Kinopalästen as we speak, but the motion picture was not actually meant for a German audience: this is but part of the clever ruse. The film was actually made in English and then dubbed back into German by the mostly Allemanic cast.

Having convinced us of their peaceful intentions through more than a half-century of “Guys, we really messed up circa 1933-1945”, the obvious intent is to swamp the English-speaking world with a film depicting the charming gentlemen fighters of the first weltkreig in order to disarm us as they prepare for their dastardly plans.

Why, as we speak, Georg Friedrich von Preussen is polishing his pickelhaube and dusting off his feather cap in preparation for this latest Prussian plot for world domination. While the Western world worried itself sick over global Islamism and the Chinese threat, little did we know that a swelling irredentism was brewing deep within the hearts of every Berliner; a tear developing in the eye at the mere mention of Tsingtao; a soul in mourning for the loss of Tanganyika. How naïve we were not to realize that all those bright young Germans spending their gap year teaching smiling Herero natives in Namibia were actually forward units of intelligence-gatherers yearning for the return of Ketmanshoop and Swakopmund to the Germanic fold.

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai

Als alle Knospen sprangen,

Da ist in meinem Herzen

Die Liebe aufgegangen.

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai,

Als alle Vögel sangen,

Da hab ich ihr gestanden

Mein Sehnen und Verlangen.

Philipp Freiherr von Boeselager, 1917-2008

Catholic Nobleman, Forester, Knight of Malta, Plotted to Kill Hitler

Philipp Freiherr (Baron) von Boeselager, the last surviving member of the conspiracy of anti-Nazi German officers, has died at 90 years of age. The freiherr‘s background and upbringing were distinctly Catholic. The Boeselagers are a Rhenish family with Saxon origins in Magdeburg. Philipp was the fourth of eight children and was educated by the Jesuits at Bad Godesborg. His grandfather had been officially censured by the Imperial German goverment for publically taking part in a Catholic religious procession.

Boeselager had most intimately been involved in the March 1943 plot to assasinate Hitler and Himmler when the the Fuhrer and the SS head were visiting Field Marshal Günther von Kluge on the Eastern Front. Boeselager, then a 25-year-old cavalry lieutenant under the Field Marshal’s command, was to shoot both Hitler and Himmler in the officers mess with a Walther PP. Himmler, however, neglected to accompany Hitler and so the Field Marshal ordered Boeselager to abort the attempt fearing that Himmler would take over in the event of Hitler’s death, changing nothing.

«Each day Hitler ruled, thousands died unnecessarily — soldiers, because of his stupid leadership decisions. And later, I learned of concentration camps, where Jews, Poles, Russians — human beings — were being killed.»

«Each day Hitler ruled, thousands died unnecessarily — soldiers, because of his stupid leadership decisions. And later, I learned of concentration camps, where Jews, Poles, Russians — human beings — were being killed.»

«It was clear that these orders came from the top: I realised I lived in a criminal state. It was horrible. We wanted to end the war and free the concentration camps.»

Boeselager later procured the explosives for the famous July 1944 plot (the subject of the upcoming film “Valkyrie“), under the cover of being part of an explosives research team. He handed a suitcase with the explosives on to another conspirator. When the bomb exploded in Hitler’s conference room, Boeselager and his 1,000-man cavalry unit made an astonishing 120-mile retreat in under 36 hours to reach an airfield in western Russia from where the aristocrat would fly to Berlin to join the other conspirators.

At the airfield, however, he received a message from his brother (Georg von Boeselager, a fellow cavalry officer who was repeatedly awarded for his consistent bravery on the battlefield) saying “All back into the old holes”, the code signifying the failure of the coup. Even more astonishingly than his swift retreat was his return, with his unit, to the front quickly enough not to raise any eyebrows. As a result, he was not known to be part of the conspiracy and escaped the gruesome tortures and executions dealt to many of his fellow conspirators.

After the war, his role in the plot was revealed and Philipp von Boeselager was awarded the Legion d’honneur by France and the Great Cross of Merit by West Germany. He joined the Order of Malta in 1946, eventually co-founding Malteser Hilfdienst, the medical operation of the German knights of the Order, and helping coordinate German pilgrimages to Lourdes.

The greater part of his post-war years was spent in forestry, and Boeselager served as head of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher Waldbesitzerverbände (the coordinating body of private and cooperative forest-owners) from 1968 to 1988. Coincidentally, he was succeeded in that post by Franz Ludwig Schenk Count von Stauffenberg, the son of the July ’44 plot mastermind.

“Valkyrie”

No, this isn’t a photograph of the latest Norumbega staff meeting, it’s a publicity shot from the upcoming United Artists film, “Valkyrie”. The film tells the story of Claus Philipp Maria Schenck von Stauffenberg, the heroic German Catholic noble who was the mastermind behind the July 20 plot against Hitler. Needless to say, there has been much anticipation over this film, especially since the lead role went to Tom Cruise, who has never quite got the knack of acting. Like Jeremy Irons, he seems to believe that completely different characters require little or no change in performance, but is mysteriously still making films nonetheless. (Cruise at least has the excuse of being a Scientologist to explain his success… what’s Jeremy Irons’s?).

Despite the poor choice of Mr. Cruise play Count Stauffenberg, the rest of the cast includes some pretty inspired choices. Playing Countess Nina von Stauffenberg is Carice von Houten (above), whom you will remember from “Zwartboek”. She’s joined by fellow “Zwartboek” actor Christian Berkel (top photo, seated far left), who played the evil General Kaütner in the Dutch film, the character responsible for the downfall of the good German, General Müntze, who was played by Sebastian Koch (better known for his role in the hit “Das Leben der Anderen”) who (pause for breath) actually played Count Stauffenberg himself in a 2004 German television production called “Stauffenberg”. Speaking of downfalls, Berkel (we’re back to him now) also played a nasty Nazi in the 2004 film “Downfall” depicting the last few days in Hitler’s bunker. [Correction: Berkel actually played Dr. Ernst-Günter Schenck, one of the good guys.] Some more of the cast…

(more…)

The Rathaus of Gladbeck

JUST SO YOU ARE aware that not all the architects hate us, let us travel to the Westphalian town of Gladbeck where the city fathers, in their infinite sagacity and wisdom and ever open to changes in inclination, have seen fit to correct the errors of the not-too-distant past by tearing down two hideous concrete boxes and replacing them with a more appropriate annex to the handsome art-nouveau Rathaus (town hall). The man to thank, apparently, is Gladbeck’s Stadtbaurat (town planning advisor) Herr Michael Stojan (a tweedy sort of fellow, it appears), who initiated the project. What a pity the directors of the Morgan Library could not exercise a similar wisdom.

Gladbeck’s ‘Willy Brandt Platz’ before the offensive structures were removed.

The new building is modern but not modernist, and has no pretensions to being the original Rathaus’s contemporary. It exhibits a certain simplicity, and while it lacks exterior ornamentation it does not suffer much from that absence. Internal courts provide natural light to the offices within, while arcades offer shelter to passers-by in the event of an impromptu opening of the heavens. With its saddleback gables, the annex complements but does not compete with the town hall it is intended to augment. Improvements such as this are deserving of our applause.

Elsewhere: Die Welt: Wie sich eine Stadt repariert (12 April 2007)

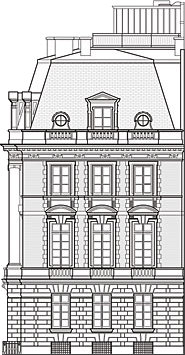

The Neue Galerie

THE RECENT PURCHASE for the Neue Galerie of Gustav Klimt’s 1907 ‘Adele Bloch-Bauer I’ (above), alledgedly for a record-breaking price of $135,000,000, gives me the perfect opportunity to write a post on the eponymously recent addition to New York’s coterie of art museums. Since its 2001 opening, the Neue Galerie has resided in the handsome 1914 beaux-arts mansion on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 86th Street, designed by Carrère and Hastings (of New York Public Library fame) for industrialist William Starr Miller and later inhabited by Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt III. In the time since the construction of No. 1048, the rest of Fifth Avenue has undergone a lamentable transformation from a boulevard of beautiful townhouses and mansions to an avenue predominantly consisting of apartment buildings. While one appreciates the inoffensive design of the pre-war buildings on Fifth, there remain a number of thoroughly opprobrious modern interlopers which offend the graceful avenue. One can’t help but pine for Fifth Avenue before the mansions came down, but we can at least give thanks for holdouts like the Neue Galerie. (more…)

THE RECENT PURCHASE for the Neue Galerie of Gustav Klimt’s 1907 ‘Adele Bloch-Bauer I’ (above), alledgedly for a record-breaking price of $135,000,000, gives me the perfect opportunity to write a post on the eponymously recent addition to New York’s coterie of art museums. Since its 2001 opening, the Neue Galerie has resided in the handsome 1914 beaux-arts mansion on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 86th Street, designed by Carrère and Hastings (of New York Public Library fame) for industrialist William Starr Miller and later inhabited by Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt III. In the time since the construction of No. 1048, the rest of Fifth Avenue has undergone a lamentable transformation from a boulevard of beautiful townhouses and mansions to an avenue predominantly consisting of apartment buildings. While one appreciates the inoffensive design of the pre-war buildings on Fifth, there remain a number of thoroughly opprobrious modern interlopers which offend the graceful avenue. One can’t help but pine for Fifth Avenue before the mansions came down, but we can at least give thanks for holdouts like the Neue Galerie. (more…)

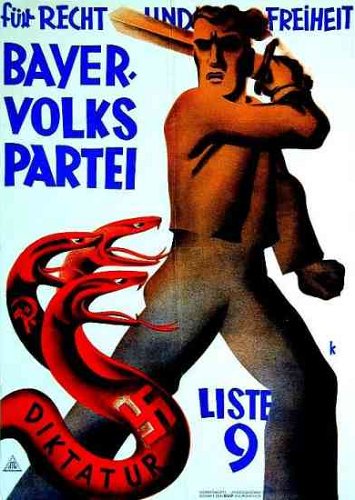

The Two Germanies

A recent post by Aelianus entitled The Two Germanies brought to mind a little-known idea which surfaced towards the end of World War II. I read in the biography of Empress Zita that a plan was hatched to divide what we now know as Germany, combining Bavaria and Austria to create a Catholic state under the restored Hapsburgs and leaving northern Germany to be a Protestant kingdom with, odd as it might perhaps seem, Lord Louis Mountbatten. Of course it’s not really that odd when one considers that the real name of the Mountbatten family is Battenberg, changed to disguise their Teutonicity during the Great War when the fervor of hatred against our cousin the Hun ran willy-nilly. While Mountbatten was born in Windosr Castle and served as First Sea Lord as well as the final Viceroy of India, he was really entirely German in terms of ancestry. His parents were Prince Louis of Battenberg and Princess Victoria of Hesse and the Rhine, while Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and the Rhine was his grandfather. By right, he was His Serene Highness Prince Louis of Battenberg, but cherishing their adopted country, the family were intimidated into dropping all German styles and titles in 1917.

Lord Mountbatten apparently took the proposal seriously enough that he began to brush up on his German, and informed Empress Zita, living in exile in the Dominion of Canada during the Second World War, of its prospects for both their families. Of course, with Yalta, nothing was ever to come of it and the closest Lord Mountbatten ever came to power, aside from his reign as Viceroy of India, was in 1967 when he was alledgedly asked to lead a coup overthrowing the Labour government. Mountbatten was highly reluctant, and nothing came of the plot. In 1979, while summering at his usual holiday home in the Irish Republic, Mountbatten was killed by an IRA bomb, along with the Dowager Lady Brabourne (aged 82), the Hon. Nicholas Knatchbull (aged 14), and Paul Maxwell (aged 15), a local boy working on the Mountbatten’s boat. He was a Knight of the Garter, a Knight Grand Cross of Bath, Order of Merit, Knight Grand Cross of the Star of India, Knight Grand Cross of the Indian Empire, Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order, and the Distinguished Service Order.

Long Live Our Holy Germany!

It was July 20, 1944, sixty years ago today, that Col. Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg was executed for his masterminding the plot to kill Adolf Hitler. Stauffenberg was a devout Catholic who became convinced that Hitler was an Antichrist.

“Fate has offered us this opportunity, and I would not refuse it for anything in the world. I have examined myself before God and my conscience. It must be done because this man is evil personified.”

His uncle, Graf (Count) Nikolaus von Üxküll, recruited him into the resistance movement after the Polish campaign in 1939. After a series of missed opportunities, Stauffenberg finally placed a bomb to kill Hitler. Unfortunately, it was moved to the other side of a strong oak table supporter, shielding Hitler from the full force of the blast. Claus Philip Maria Shenck Graf von Stauffenberg was shot by the Gestapo at half past midnight that same evening.

His dying words were “Es lebe unser heiliges Deutschland!” – Long live our holy Germany.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

- American Exuberant February 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories