Dorset

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Articles of Note: 13 March 2024

My then-flatmate was getting married the next day and much pottering-about sorting things was required but the idiosyncratic beauty of this building captured my imagination — part Norman, part Moorish. I was almost insulted that I hadn’t come across it in any of my bookish explorations.

The historian Edmund Harris covers Chideock in his lusciously illustrated post on Recusancy in Dorset and the ‘other tradition’ of Catholic church-building.

■ Generations ago it was said that the three institutions no British politician dared offend were the trade unions, the Catholic Church, and the Brigade of Guards. In 2020s Britain there is only one caste which must always be obeyed: the ageing, moneyed homeowners.

Not only do these “NIMBYs” (“Not In My Back Yard”) jealously guard their freeholds, they do whatever they can to prevent more houses being built to guard the value of their prize possessions, vastly inflated by a combination of lacklustre housebuilding and irresponsible leap in migration. As old people vote and young people don’t — and when they do, vote badly — few sensible people can find a way out of this quagmire.

It might be worth looking to the Mediterranean, where Tal Alster tells us How Israel turned urban homeowners into YIMBYs.

■ It’s disappointingly rare to see intelligent outsiders give a considered impression of the current state of play in the Netherlands — that’s Mother Holland for us New Yorkers. Too often commentators in English are either rash cheerleaders for the hard right or bien-pensant liberals eager to castigate and chastise. Both rush to judgement.

What a rare diversion then to read Christopher Caldwell — the only thinking neo-con? — attempt to explore and explain the success of Geert Wilders in the recent Dutch elections.

■ One in ten of Lusitania’s inhabitants are now immigrants, and this discounts those — many from Brazil and other former parts of the once-world-spanning Portuguese empire — who have managed to acquire citizenship through various routes.

Ukrainian number-plates are now frequently be seen on the roads of Lisbon, as far in Europe as you can get from Big Bad Uncle Vlad.

Vasco Queirós asks: Who is Portugal for?

■ Speaking of world-spanning empires, in true andrewcusackdotcom fashion, we haven’t had enough of the Dutch — but we have had enough of their wicked wayward heresies.

Historian Charles H. Parker explores the legacies of Calvinism in the Dutch empire.

■ The City of New York itself is the best journalism school there is. Jimmy Breslin dropped out of LIU after two years, eventually taking up his pen. Pete Hamill left school at fifteen, apprenticed as a sheet metal worker, and joined the navy.

William Deresiewicz argues that a dose of working-class realism can save journalism from groupthink.

■ The New Yorker tells us how a Manchester barkeep found and saved a lost (ostensible) masterpiece of interwar British literature.

■ Our inestimable friend Dr Harshan Kumarasingham explores David Torrance’s history of the first Labour government on its hundredth anniversary.

■ And finally, one for nous les normandes (ok, ok, celto-normandes): Canada’s National Treasure David Warren briefly muses that the Norman infusion greatly refined Anglo-Saxon to give us the superior English tongue we speak today.

The Wyndham Monument, Silton

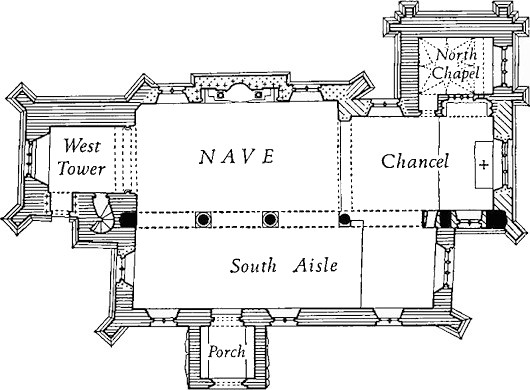

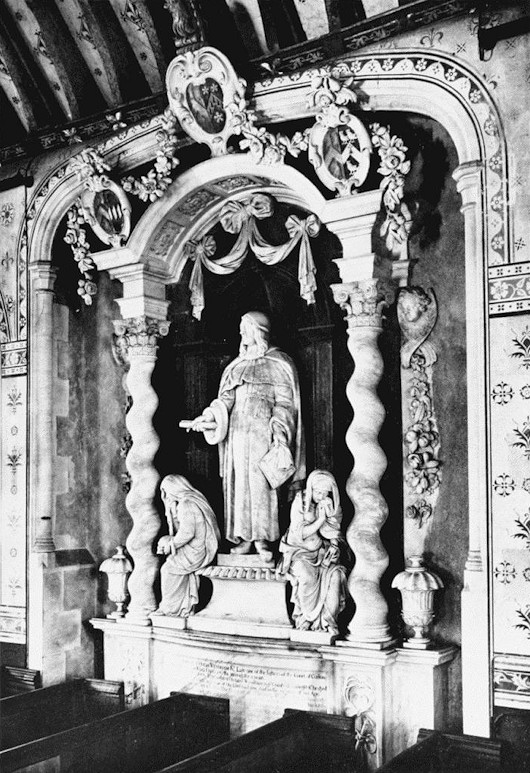

The charmingly haphazard Church of St Nicholas in Silton is home to what is arguably the finest funerary monument in Dorset not in a major church.

Sir Hugh Wyndham (1602–1684) lived through the difficult time of the Civil War and was first advanced in the law under Cromwell’s military dictatorship. It was the worst of both worlds for Wyndham, as the republican authorities never trusted him while after the Restoration his comfort with Cromwell meant he was deprived of office. Still, Charles II was no small-minded man, and after a royal pardon was granted Wyndham was appointed a Baron of the Exchequer and knighted.

The monument he left behind at Silton is is believed to be the earliest work of the Flemish sculptor Jan van Nost (also known as John Nost the elder). Sir Hugh is depicted in his judge’s robes, flanked by two mourning figures believed to represent his first and second wives. (The third wife is at least represented by having her arms impaled with Wyndham’s in one of the three heraldic sheilds gracing the monument’s surrounds.)

Nost’s sculpture was unveiled in the chancel of the parish church in 1692 but the Victorians thought it rather dominated the small sancutary. In 1869 a small recess was constructed in the north wall of the nave and the Wyndham monument was carefully moved there. The sculptor was also responsible for the monument to John Digby, 3rd Earl of Bristol, in Sherborne Abbey not far away, and one can see the parallels. The Earl, as it happened, married Rachel Wyndham, the younger daughter of Sir Hugh Wyndham.

The Kingston Lacy Massacre

Look at this majestic avenue of trees on the Kingston Lacy estate in deepest dearest Dorset. The allee was planted by the art collector, architect, Egyptologist, MP, and adventurer William John Bankes, inheritor of the estate, as a gift for his mother. There are 365 trees on one side and 366 on the other, symbolizing a regular year and a leap year. The estate is now owned by National Trust, which has decided, to the protests of old tree experts (which is to say, experts on the subject of old trees), that twenty-one of them will have to be savagely cut down on the grounds of “health and safety”.

“We don’t want to fell these trees but we have a duty,” says a spokesman for the estate. “It’s a very busy B-road and the trees are only metres from the road. We’re following good Health and Safety practice.” Pity the poor fool, and weep for the beeches of Kingston Lacy.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories