Cape Town

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The National Assembly

Despite the longer history behind the original wing of South Africa’s Parliament House, when most people think of Parliament today they think of the 1983 wing that currently houses the National Assembly. The wing was designed by the architects Jack van der Lecq and Hannes Meiring in a Cape neo-classical style similar to the rest of the building, and it is actually quite a handsome composition despite the awkwardly proportioned portico, which is too tall for its width or two narrow for its height. (more…)

Rouwkoop: An Old Cape Hodgepodge

We can deduce a lot about a power by looking at the structures it erects. The return to neo-classicism under Stalin after the earlier Russian deconstructivist architecture of the 1920s is telling, as is the almost universal (and only seemingly contradictory) adoption of socialist Bauhaus architecture for the headquarters of New York corporations in the post-war period, or the turn to Brutalism by the governments of numerous Western liberal countries in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. While the apartheid government adopted a guise of conservatism, its revolutionary re-ordering of South African society was so radical that, for example, the old Edwardian railway station in Cape Town was demolished and completely rebuilt in order to better accommodate the separation of the races.

When the Afrikaner Nationalist government was elected in 1948, it inherited one of the richest architectural traditions in the world. South African architecture, from the original Cape Dutch so praised by Ruskin, through the Cape Classical of the architect Thibault and the sculptor Anreith, and on to the attempt at a South African national style by Edwardian architects like Herbert Baker, the nation’s legacy of boukuns (building-art) is one of which any nation would be proud.

The Cape Dutch style has proved particularly versatile and easily reinterpreted in almost every age of South African history since Jan van Riebeeck planted the oranje-blanje-blou on these shores in 1652. Yet from 1948 until its final electoral demise in 1994 the National Party government erected almost no buildings in the “national style” of Cape Dutch or its aesthetic descendants. Instead, they built in the grim modernist style found everywhere else in the world, both in the liberal-capitalist West and the totalitarian-Marxist East. One need only consider the Nico Malan (now Artscape) in Cape Town, the Staatsteater in Pretoria, or the Theo van Wijk building at Unisa. (more…)

’n Indiese woning in die Moederstad

Kaapstad het ’n bietjie van die Himalajas

Twee versamelaars van suid-Asiatiese kuns het ’n subkontinentale woning in ’n Kaapstadse meenthuis geskep. Die huis was die onderwerp van ’n artikel deur Johan van Zyl in ’n onlangse uitgawe van Visi-tydskrif met hierdie foto’s van Mark Williams. Die algehele effek is ’n bietjie “over the top” vir my, maar die verleiding van die Oriënt sal nooit ophou. (Bo: ’n Paar van marmer-olifante uit Udaipur wagte by die hoofingang).

“In ’n nou keisteenstraat aan die rand van die Kaapse middestad staan ’n huis met ‘n geskiedenis” Mnr van Zyl skryf. “Toe dit in 1830 vir Britse soldate gebou is, het die branders nog digby die voordeur geklots, en nie lank daarna nie het Lady Anne Barnard hier sit en peusel aan ’n geilsoet vy wat ’n slaaf vir haar gepluk het, stellig van dieselfde boom wat nou in die huis se (nuwe) trippelvolume-glashart staan, ’n knewel met ’n vol lewe agter die blad.”

“’n Dekade of twee gelede het die reeds luisterryke geskiedenis van die huis ’n eksotiese dimensie bygekry toe twee toegewyde versamelaars — selferkende stadsjapies wat destyds in die modebedryf werksaam was — hier kom nesskop met hulle groeiende versameling Indiese oudhede.” (more…)

An Old Dutch Holdout

The sign on the façade of No. 7 Wale Street, Cape Town in this 1891 photo informs us of its status as a police station in the two official languages of the day, English and Dutch, not Afrikaans. ‘Politie’ is the Dutch word for Police, while the Afrikaans is ‘Polisie’. Afrikaans only became an official language of South Africa in 1925, but was so alongside Dutch and English until 1961, when Dutch was finally dropped.

This beautiful old Dutch townhouse, with its typical dak-kamer atop, didn’t survive as late as 1961. The Provinsiale-gebou, home to the Western Cape Provincial Parliament, was built on the site in the 1930s. Those who viewed the 2009 AMC/ITV reinterpretation of “The Prisoner” might remember an outdoors nighttime city scene after the main character leaves a diner, with the street sign proclaiming “Madison Ave.” and plenty of yellow New York taxicabs streaming past. The large arches in the background are the front of the Provinsiale-gebou.

The House of Assembly

Die Volksraad

The House of Assembly (always called the Volksraad in Afrikaans, after the legislatures of the Boer republics) was South Africa’s lower chamber, and inherited the Cape House of Assembly’s debating chamber when the Cape Parliament’s home was handed over to the new Parliament of South Africa in 1910. The lower house quite soon decided to build a new addition to the building, and moved its plenary hall to the new wing. (more…)

Swinging round the Cape Peninsula

Visual editor and blogger Charles Apple gives us a photographic depiction of his Saturday touring the Atlantic side of the Cape Peninsula, from the V&A Waterfront, to Green Point, Three Anchor Bay, Sea Point, Clifton, Maiden’s Cove, Camps Bay, Bakoven, the Twelve Apostles, Llandudno, Hout Bay, and Chapman’s Peak. The photos are good, but still don’t do justice to that beautiful part of the world. They do, however, get me pining for the Peninsula!

The Senate of South Africa

Die Senaat van Suid-Afrika

THE SENATE OF South Africa has had something of a tempestuous history, a fact which is attested to by the vicissitudes of the Senate chamber in the House of Parliament in Cape Town. The Senate formed the upper house of South Africa’s parliament from the unification of the country in 1910, in accordance with the proposals agreed to by Briton & Boer at the National Convention of 1908. Its members were originally selected by an electoral college consisting of the Provincial Councils of the Cape, the Transvaal, the Orange Free State, and Natal, and the members of the House of Assembly (the parliament’s lower house), along with a certain number of appointments by the Governor-General on the advice of the Prime Minister. When South Africa abolished its monarchy, the State President took over the appointing role held until then by the Governor-General, but the Senate remained largely intact until 1981, when it was abolished in advance of the foolish introduction of the 1984 constitution with its racial tricameralism.

The Senate made a brief comeback in 1994, when the interim constitution provided for a Senate composed of ninety members, ten elected by each of the provincial legislatures of the new provinces. The 1994 Senate, however, was replaced by the “National Council of Provinces” in the final 1997 constitution. (more…)

The Houses of Parliament, Cape Town

Die Parlementsgebou, Kaapstad.

The insignia of the Parliament of South Africa, showing the Mace and Black Rod crossed between the shield and crest of the traditional arms of South Africa.

CAPE TOWN IS justifiably known as the “mother-city” of all South Africa, paying tribute to that day over three-hundred-and-fifty years ago when Jan van Riebeeck planted the tricolour of the Netherlands on the sands of the Cape of Good Hope. Numerous political transformations have taken place since that time, from the shifting tides of colonial overlords, to the united dominion of 1910, universal suffrage in 1994, and beyond. The history of self-government in South Africa has unfolded in a well-tempered, slow evolution rather than the sudden revolutions and tumults so frequent in other domains. No building has born greater witness to this long evolution than the Parliament House in Cape Town.

The British first created a legislative council for the Cape in 1835, but it was the agitation over a London proposal to transform the colony into a convict station (like Australia) that threw European Cape Town into an uproar. The proposal was defeated, but the colonists grew concerned that perhaps they were better guardians of their own affairs than the Colonial Office in far-off London. In 1853, Queen Victoria granted a parliament and constitution for the Cape of Good Hope, and the responsible government the Kaaplanders so desired was achieved. (more…)

The Rhodes Memorial

PERCHED AMID THE bluegum trees on the slopes of Devil’s Peak in Cape Town is the memorial to one of the most brilliant & cunning men the world has ever produced. Cecil John Rhodes may have been born in Bishop’s Stortford, England, but his worldly glories all emanated from the Cape of Good Hope, and so it’s appropriate that his memorial stands here in Cape Town. His first commercial enterprise in South Africa was founding the Rhodes Fruit Farms (now Rhodes Food Group) which still exist on the road from Stellenbosch to Franschhoek, and has since expanded throughout the Western Cape, and to the Transvaal and Swaziland. But it was his creation of the diamond monopoly De Beers out of the Kimberley mines that made him one of the wealthiest men in the world. Ten years after being elected to the Cape Parliament, he was made Prime Minister of the Cape in 1890, but his catastrophic and illegal attempt to seize the independent Transvaal in 1895 forced his resignation from politics in disgrace. (more…)

Leeuwenhof

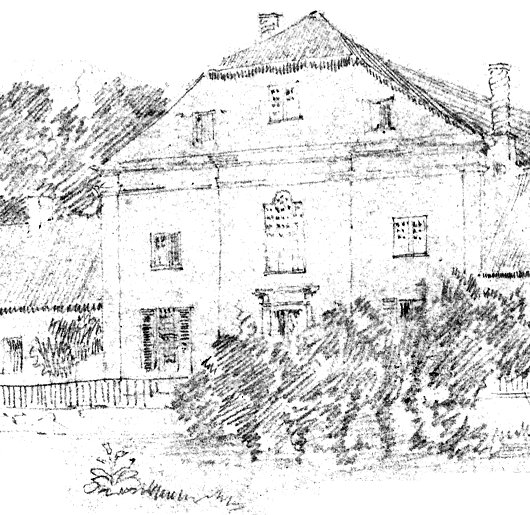

One of the better aspects of the job of Premier of the Western Cape is Leeuwenhof, the official residence that comes with the job. The estate on the slopes of Table Mountain dates from the days of the Dutch East India Company. That renowned governor of old, Simon van der Stel (after whom both Simonstad & Stellenbosch are named), granted the land to Guillaum Heems, a free burgher, to ‘clear, plant, plough, develop and work’. Heems christened the land Leeuwenhof — “Lions Court” — but sold it just two years later to Heinrich Bernhard Oldenland, Master Gardener of the Company’s Garden and Superintendent of Works for the Dutch East India Company.

Oldenland died just a few months after purchasing Leeuwenhof, and it passed into the hands of the fiscal Blesius, whose widow’s death put the estate under a series of masters until it was sold it for 14,000 guilders to Johan Christiaan Brasler, a Dane. Brasler enjoyed a good many years there in prosperity of late-eighteenth-century Cape Town, a period when the building of stately homes, townhouses, and government buildings became (as Cornelis de Jong put it at the time) “a passion, a craziness, a contagious madness that has infected nearly everyone”. This was the age of Thibault, Anreith, and Schutte — the true golden age of Cape Town’s stately finery. Inspired by the “madness” of which De Jong tells, the Dane Brasler converted the humble farmhouse of Leeuwenhof into the dignified abode we know today. (more…)

The Groote Kerk

Dr. van der Merwe, moderator of the Dutch Reformed Church, poses in the splendidly carved pulpit of the Groote Kerk in Cape Town.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories