Buenos Aires

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

La Rural 2024

The greatest event of the bonaerense calendar — nay, the entire Argentine year — is La Rural, the annual agricultural show of the Sociedad Rural Argentina. The silverine republic is a farming powerhouse and this show is probably second only in greatness to the annual Salon international de l’agriculture in Paris.

It is when the campo comes to town in all its glory, and mixes with the city-dwellers too. As the photographer Thomas Locke Hobbs put it, the crowd at La Rural is pretty much fifty per cent gaucho, fifty per cent Ralph Lauren.

Horses, cows, pigs, every beast of the Pampas, and every man that can ride, shoot, skin, or hunt it, manifests themselves somewhere here on the exhibition grounds in Palermo between the American embassy and the Plaza Italia.

Over a million visitors are expected across the ten days of the exposition, which are currently only halfway through.

Such are the glories of this great festival of Argentina’s living traditions I thought it worth sharing a few photos from the SRA’s own photographers.

And a gran saludo to the president Nicolas Franco Pino and all his team at the Sociedad Rural.

A Scene in Buenos Aires

A hatted woman sits on a balcony, looking away out over the Plaza de Mayo, the Cathedral of Buenos Aires, and the city beyond.

It looks like the sort of thing taken by one of the French photographers, but in fact it is by a total amateur: Henry Dart Greene, the son of the Californian architect Henry Mather Greene (of Greene & Greene).

From 1928 to 1931, Dart Greene worked for the Argentine Fruit Distributors Company, founded by the Southern Railway to make use of the individual smallholdings long its line.

Upon his death, Dart Greene’s papers were deposited in the library of the University of California at Davis including this photograph from his time in Argentina.

While the building it’s taken from has been demolished and replaced with a bank, most of what you see beyond is still there.

All Change for Argentine Newspapers

BsAs Herald emerges as weekly as La Nación goes tabloid

Not Lucas de Soto

One of the saddest pieces of news to hit the Cusackosphere in 2016 was word that the Buenos Aires Herald was ending its 140th year by moving from daily to weekly production. The English-language Herald has been a stalwart of its city and country and, though little known abroad, has ranked among the finest newspapers in the world. But from 2007, when Charleston’s Evening Post Publishing Company sold the Herald onwards to controversial businessman Sergio Szpolski, the paper found itself in increasingly chaotic situations. Robert Cox, Herald editor in the difficult period from 1968 to 1979, said what happened to the paper was “like a car crash”, and blamed the papers owners.

My favourite feature of the Herald was Martin Gambarotta’s weekly ‘Politics and Labour’ column — a witty and insightful peek behind the curtains of Argentine public life. Like Miriam Lord’s Dail sketches for the Irish Times, one wished it was possible to redeploy Gambarotta’s pen at will towards whichever corner of the globe one happened to be situated in.

As if that weren’t bad enough, the republic’s venerable broadsheet La Nación announced around the same time its conversion to a smaller compact size. The centre-right daily is the most prestigious in Argentina since the demise of La Prensa under Peronist persecution. While its weekend editions will maintain their broadsheet format, from Monday to Friday La Nación will be printed in a compact format similar in size to a tabloid.

Marcelo García’s explanation of the changes at the Herald can be found below. (more…)

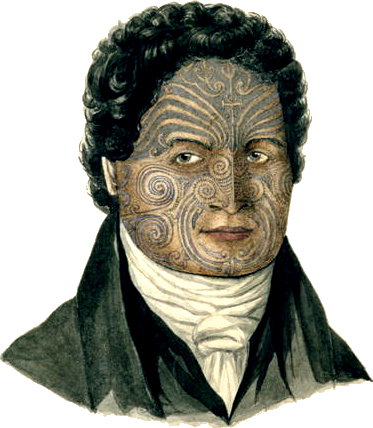

A Maori in Buenos Aires

The Argentine stopover of Te Pēhi Kupe

So  far as I can tell, the first Maori to visit Argentina (or the United Provinces of the River Plate as it was then called) was the young nobleman Te Pehi Kupe in October 1824. (The name is spelt varyingly as Te Pēhi Kupe, Tupai Cupa, Te Pai Kupa, and Tippahée Cupa). Te Pehi was born on the North Island, probably around 1795, and was a senior-line descendant of Toarangatira (founder of the Ngati Toa tribe) as well as an uncle to the more famous Ngati Toa chief, Te Rauparaha.

far as I can tell, the first Maori to visit Argentina (or the United Provinces of the River Plate as it was then called) was the young nobleman Te Pehi Kupe in October 1824. (The name is spelt varyingly as Te Pēhi Kupe, Tupai Cupa, Te Pai Kupa, and Tippahée Cupa). Te Pehi was born on the North Island, probably around 1795, and was a senior-line descendant of Toarangatira (founder of the Ngati Toa tribe) as well as an uncle to the more famous Ngati Toa chief, Te Rauparaha.

Most of New Zealand was a bit of a mess at the time, as various Maori tribes fought each other for land to grow potatoes on. Te Pehi Kupe, being a chief and military leader, was desirous to go to Europe in order to obtain weapons for his tribe. When the British ship Urania went past the southern tip of the North Island, Te Pehi forced himself aboard despite the violent resistance of the ship’s officers and crew. When asked what he desired by the Urania‘s captain, Richard Reynolds, Te Pehi replied in broken English, “Go Europe, see King George”.

Captain Reynolds did not think this a good idea and, knowing the Maori to be good swimmers, tried to have him thrown overboard, but the native nobleman’s physical strength prevented this. (And a good thing, too, as Te Pehi managed to save the Captain from drowning later on in the journey.)

The Urania made its return to England with Te Pehi Kupe aboard, calling at Lima and then sailing around the Southern Cone, where they called in at Buenos Aires. George Thomas Love provides us with an account of the Maori’s arrival in A Five Years’ Residence in Buenos Ayres (published in 1827):

In the month of October, 1824, the visit of a New-Zealand chief to Buenos Ayres, by name Tippahée Cupa, attracted much curiosity; he arrived in the British ship Urania, Captain Reynolds. Tippahée came alongside this ship in Cook’s Straits, with a war canoe filled with his people, and, in spite of the remonstrances and even force used by Captain R. refused to quit the vessel, expressing his determination to proceed to England. He bade his followers an affectionate adieu, enjoining obedience to his successor during his absence. The Urania sailed for London with her passenger the 8th December, 1824.

Tippahée, when he first arrived in Buenos Ayres, was clothed in an old red coat, formerly belonging to a London postman. The English paid him many attentions, inviting him to dine at their houses, and new clothing him. His behaviour at table was easy and unembarrassed; and, when requested, he would perform the dances and war songs of New Zealand. He understood a little of the English language, and spoke a few words of it; his intelligent manners, and circumspect conduct, rendered him an universal favourite.

On the map he could trace the ship’s course from New Zealand to Lima and Buenos Ayres. He knew an Englishman immediately; the Spaniards he did not much admire, fancying they viewed him with contempt, and was glad to get among Englishmen. His age is about forty; he possesses amazing strength; his tattooed face and appearance always attracted a crowd after him in Buenos Ayres.

On board ship he was found very useful, doing all sorts of work, but he positively declined to go aloft. The fate of Captain Thompson, and the crew of the British ship Boyd, ought to bespeak caution in using coercion with these savage chieftains of New Zealand.

In Cruise’s book of New Zealand, Tippahee was shewn a picture of a chief of his country, with which he was greatly delighted. The object of his journey to England is to solicit arms and ammunition, to place him upon a par with a rival chief, who possesses those requisites.

In England, Te Pehi was indeed presented to King George IV. He also learned to ride, visited factories, was given many gifts, and survived the measles before leaving England aboard the Thames on 6 October 1825. In Te Pehi’s absence abroad, peace had been agreed between the Ngati Toa and their Ngati Apa rivals. Ngati Toa eyes soon turned to the South Island, and during the military campaign there Te Pehi Kupe was killed, his body cooked and eaten, and his bones turned into fish hooks.

Still, at least he enjoyed Buenos Aires before he died.

Linea A Loses Its Lustre

Century-Old Buenos Aires Subté Carriages Being Replaced

Disappointing news from Buenos Aires: having reached their hundredth year of service, all the original carriages on Linea A of the Subté (Line A of the Buenos Aires Underground) are to be replaced. Linea A was the first urban underground railway in South America, built by the Anglo-Argentine Tramways Company in 1913. The cars were built between 1911 and 1919 by the Belgian company La Brugeoise et Nicaise et Delcuve and were designed to be used as both tram and underground cars: low entrances at the ends permitted street-level access while middle doors were at platform level for the Subté. In 1927, the carriages were altered for underground-only use.

From 1921 onwards, the rolling stock underwent seven different refurbishments, but all with the original chassis and mechanics, and keeping the traditional 1910s interior. La Brugeoise having since been subsumed into Bombardier, original parts are no longer available for purchase, so they are custom-made at the Polvorín workshop of the Subté operating company. Of the entire Buenos Aires Underground network, these cars have the lowest rate of mechanical failure.

The La Brugeoise carriages are being gradually replaced over the next two months, and Line A will run with entirely new rolling stock from March of this year.

Monument to the Latin Genius

The Palacio Barolo, Avenida de Mayo, Buenos Aires

THE PROSPECT WAS horrifying. The year was 1919, and Europe had only just brought to an end an orgy of self-destruction lasting several years. The negotiations to conclude a peace treaty at Versailles were ongoing, but from abroad it looked as if the continent had descended into a trend of violence, decline, and destruction. That year, Luis Barolo, an Italian textiles manufacturer who had immigrated to Argentina, commissioned his fellow-countryman Mario Palanti to design a fascinating and mysterious structure as a monument to “the Latin Genius” Dante Alighieri — a repository in the New World for the poet’s legacy as the continent that gave him birth slid into oblivion. (more…)

BA: “an old-fashioned European city”

“Argentina has to be one of the most underrated travel destinations,” Michael Buerk writes in his salute to Argentina in today’s Daily Telegraph. An excerpt:

AT THE HEART OF IT ALL IS Buenos Aires, one of the world’s most exciting cities. I was there for months during the Falklands War, reporting for the BBC. They were praying for me in our local church. If only they had known how close I had come to eating myself to death – those steaks are huge – they would have prayed even harder.

AT THE HEART OF IT ALL IS Buenos Aires, one of the world’s most exciting cities. I was there for months during the Falklands War, reporting for the BBC. They were praying for me in our local church. If only they had known how close I had come to eating myself to death – those steaks are huge – they would have prayed even harder.

It is an intensely Anglophile country, and was even then. The upper crust didn’t want to argue about the sovereignty of the Falklands (any more than they would want to argue now about oil drilling); they wanted to know where in Jermyn Street to order their cavalry twills. The hundreds of thousands of descamisados (literally, “shirtless ones”) who packed the Plaza de Mayo screaming for Mrs Thatcher’s blood would break off when they saw the BBC logo on the camera to make sure they had got the lyrics to “Hard Day’s Night” exactly right. The city’s biggest department store was called Harrods, the poshest club was (and is) the Hurlingham and the most popular film during the war was “Chariots of Fire”.

The veterans of the Malvinas, portly and grey-haired now, camp out in the Plaza de Mayo, still begging for better pensions. Porteños (the locals’ name for themselves) call them “the whiners”. The memorial to the 700 or so Argentine dead is prominent enough, but it is just a list of names and the eternal flame has long since gone out. It faces the great clock, built by the British a century ago (with a movement copied from Big Ben). The locals still call it the English Tower, even though it was officially renamed after the conflict. The cause still rankles, but the war is an embarrassment.

There’s poverty in the suburbs but, at its heart, Buenos Aires is a grand city, laid out in the days when its wealth and its future seemed unlimited. The world’s widest avenues, finest opera house, most opulent fin de siècle town houses, and – my idea of heaven – Italian restaurants cooking the world’s most wonderful meat. (Try La Brigada, where they cut the tenderloin with spoons. And don’t order “Baby Beef” looking for a light meal; it weighs in at just short of a kilo.)

It’s an old-fashioned European city, with a café society oddly short of dark faces. The original natives, and the African slaves, were wiped out or pushed out. The most prominent of the country’s remaining blacks (70 or so, it is said) was arrested at the airport recently because officials thought her Argentine passport must be a forgery.

The city is full of grand monuments, mostly to the chancers who snatched independence when Spain had its back turned, bowing the knee to Napoleon. They are as extravagantly memorialised in death as they were spurned in life; nearly all of them died in exile.

Argentina’s real heroes can be seen, stuffed, in the colourful old dock area, La Boca. Life-size models stare at you from the shops and down from the balconies. There are just three of them, and a tawdry trio they are. Eva Duarte Peron, of course, the actress who slept her way to the bottom of the movie business and into the life of a crypto-fascist colonel on the make; a long-dead tango warbler called Carlos Gardel; and Maradona, the squat footballer with the hand of God and the soul corroded by cocaine. Two of them died young; the third is still trying.

Death is a big thing in Argentina. La Recoleta cemetery is worth the trip in itself. It’s an entire suburb of gloriously overblown mausolea; a gentleman’s club for the dead, even harder to get into than the Garrick. Evita is there, in the Duarte family tomb. Her father’s relatives famously said they wouldn’t be seen dead with her; now she’s banged up with them for all eternity. There’s a new museum to Evita that’s worth seeing, with a pinch of salt.

I would dispute Bs.As. being “an old-fashioned European city”. It is instead a rather vigorous American city that retains many of the best attributes of an old-fashioned European city.

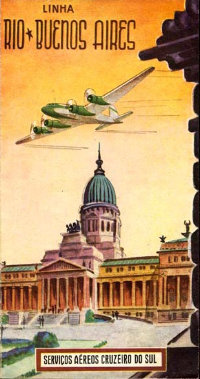

Avenida de Mayo

Looking down the Avenida de Mayo towards the Argentine Congress in the 1910s.

A humble house in Buenos Aires

Landowner Ignacio Pirovano rests in his family’s Buenos Aires townhouse, 1964.

A Sunday Afternoon in Buenos Aires

A sidewalk café on a Sunday afternoon, Buenos Aires, 1964.

The Municipalidad

This news photo showing a protest (what else?) of bus drivers on the Avenida de Mayo in Buenos Aires gives a good view of the capital’s city hall. The municipal headquarters is located between the Plaza de Mayo and the former home of the newspaper La Prensa; the Casa Rosada, Argentina’s presidential palace (officially called Government House, Casa del Gobierno) can be seen in the distance at the end of the square.

I’ve long thought they should reduce the auto space by two lanes, one on each side, and double the width of the sidewalks — but that would probably make the bus drivers even more irate.

La Rural

The 122nd Exhibition of the Sociedad Rural Argentina

One of the highlights of the Argentina calendar is the Rural Exposition or “La Rural” which takes place every year at the Buenos Aires showgrounds of the Sociedad Rural Argentina. La Rural is one of the few events which takes up the entirety of the Society’s thirty-acre home nudged between Palermo Viejo and Palermo Nuevo and facing onto the Plaza Italia. Lasting from July 24 to August 4, with admission just 13 pesos (about $4.25 or £2.30), the show usually attracts a million visitors over its thirteen days.

Los Patricios – The Patricians

In my carelessness last week, I mistakenly wrote that the presidential guard in Buenos Aires are the “Patricios” regiment, when (as Cruz y Fierro corrected me) it is actually the Regiment of Horse Grenadiers. The First Regiment of Infantry “Patricios” (literally “Patricians”) is the oldest regiment in the Argentine Army and predates by ten years the country’s Declaration of Independence. It was first assembled as the “Legion of Volunteer Urban Patricians” in 1806 to repel the English invasions of that year.

In these two photos you can see the “Patricios” performing the somewhat-rare ceremony of the changing of the guard at the Cabildo, across the Plaza de Mayo from the Casa Rosada.

andrewcusack.com: Argentina

Changing the Guard in Buenos Aires

The changing of the guard at Government House, Buenos Aires, the Presidential Palace of the Argentine Republic more popularly known as the ‘Casa Rosada’ due to its pink hue.

The Patricios regiment who provide the presidential escort were founded in 1806, making them as old as New York’s 7th Regiment. (Unlike the 7th, however, Los Patricios not only still exist but indeed flourish as the oldest regiment in the Argentine Army).

UPDATE: Cruz y Fierro corrects me that the presidential guard are formed by the Regiment of Horse Grenadiers, not Los Patricios. I have often confused the two in the past, I must admit.

andrewcusack.com: Argentina

A Lawyer’s Studio in Recoleta

This property in the Recoleta neighborhood of Buenos Aires was once a residential apartment until a multi-generational family of lawyers bought and transformed it into a law office. (more…)

Hipódromo Argentino de Palermo

THE PALERMO RACETRACK is the main center for equestrian events in Buenos Aires. It was first built in 1876. In 1908 the current main stand was built to the beaux-arts design of a French architect, Louis Faure Dujarric. The Argentine Grand National, a race of 2,500 meters, has been run here annually since 1885. (more…)

The Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires

Finest opera house of the New World

Am I old-fashioned, or aren’t footmen not supposed to smile?

This usher knows precisely how much (which is to say, how little) emotion to show.

But now, everyone to their seats…

The magnificent Teatro Colón is currently closed for refurbishment until 25 May 2008, when the most prominent opera house under the Southern Cross will reopen brighter and better than ever.

St. Alban’s College: 1907-2007

ASTUTE READERS OF the Buenos Aires Herald, itself over one hundred and thirty years old, would have noticed in the paid announcements section a week ago Sunday the following notification: (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories