Argentina

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

A humble house in Buenos Aires

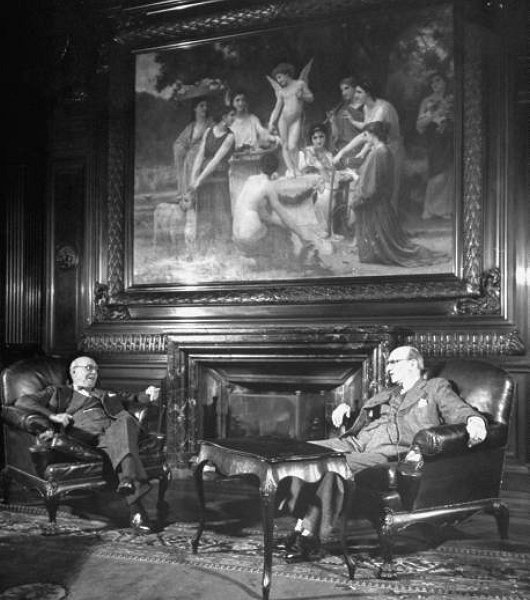

Landowner Ignacio Pirovano rests in his family’s Buenos Aires townhouse, 1964.

A new look for Argentina’s Herald

The Buenos Aires Herald is one of those newspapers that, by the grace of God, simply must continue existing no matter what horrors befall the newspaper industry as a whole. Finding up-to-date information on Argentina, in English, can be exceptionally frustrating and I had the Sunday version of the paper sent to me in New York every week; perfect reading for the train ride into work. Martin Gambarotta’s “Politics & Labour” column has to be one of the most informative and well-written political columns in any English-speaking newspaper. I also enjoyed the paid announcements section, informing readers of golf tournaments in aid of the Hospital Británico, meetings of the British-Argentine Chamber of Commerce, and when the next convocation of the South America Piping Association would be held. That said, when the Herald started denominating their subscription fee in dollars instead of pesos, I had to call it quits — though very reluctantly.

All the time while perusing the newspaper, however, I kept thinking “This could be better…”. Readers know how design-obsessed I am, especially when it comes to newspapers, and the Buenos Aires Herald would be such a better newspaper if they just tweaked a few things: a more judicious font choice, standardized white-spaces between columns, a few meliorations here and there. But now they’ve gone and redesigned the thing — without seeking the input of this devoted fan! — and they’ve got it all wrong. (more…)

Argentina Mourns an Honest Man

RAÚL ALFONSÍN WAS often a stumbling, bumbling leader when he served as President of the Argentine Republic but, in a country of rampant corruption and abuse, his personal integrity was unassailable. It was probably for that reason that Argentines came on to the streets of Buenos Aires in April to mourn the loss of, certainly not the greatest statesman of the country’s history, but at least something simple: an honest man. For more on the late president, see my piece over at InsideCatholic.com. (more…)

A Sunday Afternoon in Buenos Aires

A sidewalk café on a Sunday afternoon, Buenos Aires, 1964.

Victory in Uruguay

Leftist president defies his own coalition, vetoes bill to legalize abortion.

The President of Uruguay, Dr. Tabaré Vázquez, has vetoed a bill passed by the two chambers of the country’s congress that would overturn the ban on abortion. Pre-natal infanticide has been illegal in Uruguay since 1938, and the left-wing Frente Amplio coalition that has a congressional majority sought to enact one of the most permissive abortion laws in Latin America. While President Vázquez, an oncologist by training, is a member of the Frente Amplio party, his constituent group in the alliance is the Christian-Democratic Party which proclaims as part of its platform an “absolute respect for human rights”. The veto sends the bill back to the congress, where the Frente does not have the two-thirds majority necessary to override the veto.

Our Lady of Luján

Fr. Finigan tells us that a million young people joined a recent pilgrimage to the Shrine of Our Lady of Luján, forty miles west of Buenos Aires. I had the privilege of being a pilgrim there myself on the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin in the summer (or rather winter) of 2001.

The Good Priest of Blackfen also recently pointed out an article from La Nacion about the twenty-fifth anniversary of the apparitions at San Nicolas (below).

The Municipalidad

This news photo showing a protest (what else?) of bus drivers on the Avenida de Mayo in Buenos Aires gives a good view of the capital’s city hall. The municipal headquarters is located between the Plaza de Mayo and the former home of the newspaper La Prensa; the Casa Rosada, Argentina’s presidential palace (officially called Government House, Casa del Gobierno) can be seen in the distance at the end of the square.

I’ve long thought they should reduce the auto space by two lanes, one on each side, and double the width of the sidewalks — but that would probably make the bus drivers even more irate.

La Rural

The 122nd Exhibition of the Sociedad Rural Argentina

One of the highlights of the Argentina calendar is the Rural Exposition or “La Rural” which takes place every year at the Buenos Aires showgrounds of the Sociedad Rural Argentina. La Rural is one of the few events which takes up the entirety of the Society’s thirty-acre home nudged between Palermo Viejo and Palermo Nuevo and facing onto the Plaza Italia. Lasting from July 24 to August 4, with admission just 13 pesos (about $4.25 or £2.30), the show usually attracts a million visitors over its thirteen days.

High Drama in Argentina’s Halls of Power

IT IS AN age-old question: what happens when an irresistible force meets an immovable object? The force in question is the farming community of Argentina, once among the agricultural powerhouses of the world, and the object is the country’s slippery presidential couple, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and her husband (and predecessor in the top job) Néstor Kirchner. From all the way back in March, the Kirchners have been locked in a bitter dispute with the farming sector of the country since the presidential couple unilaterally imposed a massive tax on soy exports.

The Kirchners deride the farmers as “oligarchs” and claim that the exorbitant tax on one of Argentina’s most successful commercial sectors will be redistributed to the poor. Of course it would be irresponsible to simply take from the haves and give to the have-nots; the money raised would only go to the deserving poor, namely those who happen to support the Kirchner regime. Along the way, every cog in the machine will take his fair share, with a respectable amount left over to fatten the calves (metaphorically speaking) of the Kirchnerite street operators who quite openly buy votes during election time and pay union members to show up at pro-government rallies in between.

Argentine farmers protesting the Kirchner soy tax.

Argentina’s Voice: La Prensa

TIME magazine, 26 October 1942

In the ornate Paz family crypt in Buenos Aires’ comfortable La Recoleta cemetery, honors came thick last week to the late José Clemente Paz, founder of Argentina’s La Prensa. The Argentine Government issued a special commemorative postage stamp. Nationwide collections were taken to erect a monument. U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull sent a laudatory cable, as did many another foreign notable. It was the 100th anniversary of the birth of Argentina’s most famous journalist.

In the ornate Paz family crypt in Buenos Aires’ comfortable La Recoleta cemetery, honors came thick last week to the late José Clemente Paz, founder of Argentina’s La Prensa. The Argentine Government issued a special commemorative postage stamp. Nationwide collections were taken to erect a monument. U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull sent a laudatory cable, as did many another foreign notable. It was the 100th anniversary of the birth of Argentina’s most famous journalist.

Although Don José has been dead for 30 years, the newspaper he founded 73 years ago has not changed much. La Prensa is THE Argentine newspaper, is one of the world’s ten greatest papers.

Polish, Curiosity, Comics.

A cross between the London Times and James Gordon Bennett’s old New York Herald, La Prensa is unlike any other newspaper anywhere. In its fine old building the rooms are lofty and spiced with the odor of wax polish, long accumulated. Liveried flunkies pass memoranda and letters from floor to floor on an old pulley and string contraption. But high-speed hydraulic tubes whip copy one mile from the editorial room to one of the world’s most modern printing plants—more than adequate to turn out La Prensa’s 280,000 daily, 430,000 Sunday copies.

Argentines are minutely curious about the world. Although newsprint (from the U.S.) is scarce, La Prensa usually carries 32 columns of foreign news—more than any other paper in the world. Four years ago most was European—today New York or Washington has as many datelines as London.

La Prensa’s front page is solid (save for a small box for important headlines) with classified ads. So, usually, are the following six pages—one reason the paper nets a million dollars or more annually. Lately La Prensa has made some concessions to modernity: it now carries two comic strips, occasional news pictures.

Deliveries, Duels, Discussions.

La Prensa will not deliver the paper to a politician’s office; he must have it sent to his home. It will not call for advertising copy. No local staffman has ever had a byline.

South American journalism is more hazardous than the North American brand. La Prensa’s publisher and principal owner, Ezequiel Pedro Paz, Don José’s son, has twice been challenged to a duel. Because he is a crack pistol shot, neither duel was fought. Now over 70, Don Ezequiel shows up at the paper punctually at 5 p.m. for the daily editorial conference with Editor-in-Chief Dr. Rodolfo N. Luque. Present also is his nephew and heir-apparent, handsome Alberto Gainza (“Tito”) Paz, 43, father of eight and ex-Argentine open golf champion. Significantly, La Prensa’s owner-publishers visit their editor-in-chief and not vice versa.

La Prensa’s foreign affairs editorials often wield great influence, but have not budged the isolationism of President Ramón Castillo. The paper has supported Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, pumped for the United Nations, denounced the totalitarians. But it speaks softly. When Argentina’s President Castillo gagged the press with a decree forbidding editorial discussions of foreign events, admirers of Don José recalled how he once suspended publication in protest at another Argentine President’s like decree. If old Don José were now alive, declared they, he would again have stopped La Prensa’s presses rather than submit to Castillo’s regulations. — TIME, Oct. 26, 1942

TIME magazine, 16 July 1934

Prensa Presses

On the roof of the imposing La Prensa building in Buenos Aires’ wide Avenida de Mayo is a large siren. Its piercing screech, audible for miles, heralds the break of hot news. Long ago a city ordinance was passed forbidding use of the siren and the publishers rarely sound it nowadays. But when some world-shaking event takes place, La Prensa’s horn shrills and a Prensa office boy trots downtown to pay the fine before its echo has died away.

Last week the fingers of La Prensa’s acting publisher, Dr. Alberto Gainza Paz, itched to push the siren button. There was much to celebrate. Not only was it Nueve de Julio, Argentina’s Independence Day, but potent old La Prensa was formally inaugurating a new $3,000,000 printing plant, finest in South America. Its holiday edition ran to 725,000 copies— 150,000 more than its previous record.

The plant is housed in a new building a half mile from the main office, in the rent-cheap industrial district. It is linked to the editorial rooms by pneumatic tubes. The installation includes a 21-unit Hoe press similar to that of the New York World-Telegram. The press is driven by 56 motors, is fed by 63 rolls of newsprint and two six-ton tanks of ink. A normal edition of 250,000 copies (400,000 Sunday) is spewed out in considerably less than an hour. Since Buenos Aires is so far from the Canadian pulp market, La Prensa keeps on hand up to 7,500 tons of newsprint, enough to supply its needs for three months or, in emergency, to produce a smaller paper for a year.

Completion of the new plant marked the almost complete retirement of La Prensa’s publisher and principal owner, Don Ezequiel P. Paz. Son of the late Dr. José C. Paz, who turned out the first copy of La Prensa 65 years ago on a tiny hand press, Don Ezequiel started to work around the shop as a youngster in 1896, took full charge while still a young man. He devoted his life completely to his newspaper, spent nearly all his waking hours in his incredibly ornate office, denied himself to practically all callers except his editors. Past 60, of nervous temperament, he lives nearly half the year at his French estate near Biarritz. On his transatlantic trips he customarily takes a large party of relatives, and for the sake of his diet, a cow. The cow makes the round trip but must be sacrificed in sight of her native land because of Argentina’s rigid quarantine against all imported cattle. Don Ezequiel sailed for Biarritz last month, regarding the new plant as perhaps the last important milestone in his publishing career. Childless, he turned his responsibilities over to his nephew, youthful Dr. Alberto Gainza Paz, whom he carefully tutored as he himself had been trained by Founder José. So puny in boyhood that he was not expected to live. Dr. Gainza made of himself one of the foremost amateur athletes in Buenos Aires.

Beyond dispute La Prensa is the leading newspaper in South America, is read throughout the continent. Sternly independent, it truckles to no political party, even refuses to accept political advertising on the ground that if any politician is really as good as he claims, he is legitimate news and will be reported accordingly.

To U. S. newsreaders, a typical copy of La Prensa is a curious sight. Prime headlines are massed in a six-column box on the front page, which is otherwise filled with classified advertisements. The “classifieds” run through the next six pages and supply the wherewithal for Publisher Paz’s proud boast that La Prensa is independent of large commercial advertisers. The news pages begin with a lengthy, learned article which most readers skip, but which is supposed to wield strong influence in high places. The news columns proper are top-heavy with foreign news. Probably no other newspaper in the world spends so much money on cable tolls—a fact partly due to Argentina’s cosmopolitan population. La Prensa demands important political speeches in full. It “discovered” Albert Einstein for the world press by first requesting United Press to interview him on his theory of relativity 15 years ago. After La Prensa printed it, U. P. decided to try Einstein on its U. S. clients. La Prensa gives any amount of space to amateur sports, demands play-by-play coverage on important chess matches, but refused Argentina’s Prizefighter Luis Firpo more than the barest mention even at the height of his popularity. It prints voluminous market news, lottery drawings, crossword puzzles, no comics except on Sunday. Its newsphotos are rare and inferior. On Sunday it offers rotogravure in color.

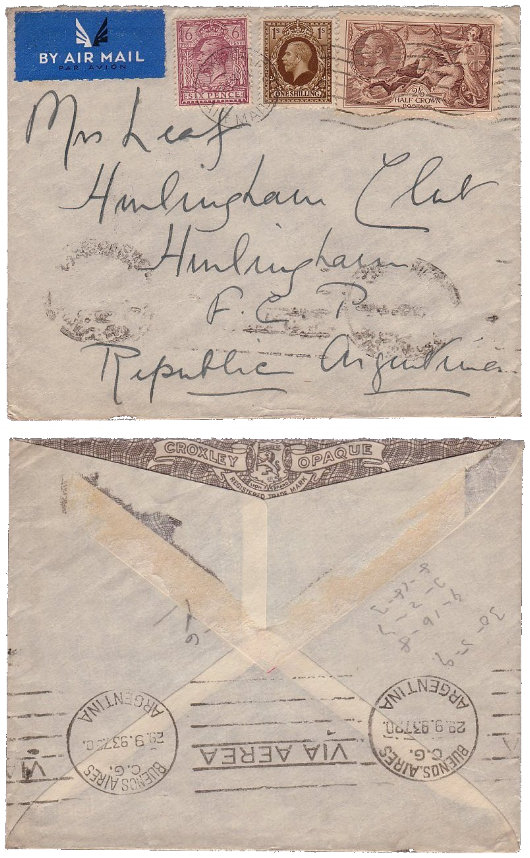

Employing no advertising salesmen, La Prensa never solicited an advertisement. Until a few years ago it would not permit advertisers to use large display type. It rejected a substantial Wrigley campaign because it hesitated to introduce the gum-chewing habit to Argentina. It saw no sense in a Quaker Oats breakfast food advertising program because Argentinians do not eat breakfast. However, La Prensa does print many an advertisement of doctors specializing in venereal diseases. La Prensa is one of the wealthiest newspapers in the world. The Paz family took from it enough to live in ease, plowed back huge sums for improvements and. notably, social services. One of the oldest services is a general delivery postal service, begun after the great immigration of the 1860’s when the Argentine post office proved hopelessly inadequate. To this day a letter addressed care of La Prensa will reach any Argentinian of known residence. Also La Prensa maintains free medical and surgical clinics for the poor, free legal service, and a free three-year music school. Its building houses banquet rooms, lecture halls, library, gymnasium.

The Paz family likes to regard La Prensa as Argentina’s property, themselves as hired managers. — TIME, July 16, 1934

CUSACK’S NOTE: La Prensa was confiscated by Peron’s dictatorship and its assets given to the Peronist CGT trade union. The family’s assets were restituted in 1988 and the newspaper refounded, but its readers had by then moved elsewhere and the La Prensa continues to this day in a much reduced form; its old headquarters on the Avenida de Mayo is now the Casa de la Cultura. The conservative La Nacion is now the only broadsheet in Argentina.

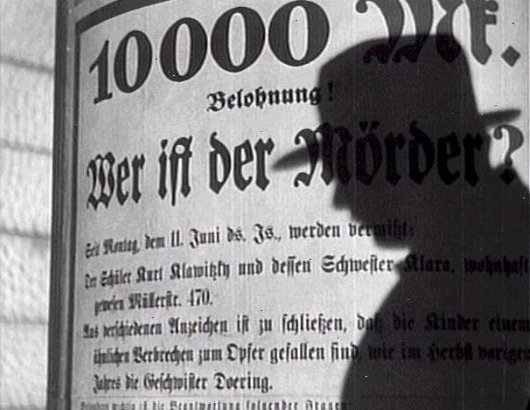

«Metropolis» rediscovered

Fritz Lang’s «Metropolis» was one of the most groundbreaking films of the silent era, and so the news that scenes previously lost have been rediscovered is most welcome. While «Metropolis» is one of those films that is perhaps best appreciated if only viewed once, I certainly look forward to a restored version being released in the next few years.

Still, my favorite of Fritz Lang’s works remains the classic «M», a sound film released in 1931, a few years into the talkie era. Peter Lorre is at his best in the starring role, and of course with Lang at the helm, «M» is expertly shot. Those whistled notes from Peer Gynt are never the same again after seeing this film!

Los Patricios – The Patricians

In my carelessness last week, I mistakenly wrote that the presidential guard in Buenos Aires are the “Patricios” regiment, when (as Cruz y Fierro corrected me) it is actually the Regiment of Horse Grenadiers. The First Regiment of Infantry “Patricios” (literally “Patricians”) is the oldest regiment in the Argentine Army and predates by ten years the country’s Declaration of Independence. It was first assembled as the “Legion of Volunteer Urban Patricians” in 1806 to repel the English invasions of that year.

In these two photos you can see the “Patricios” performing the somewhat-rare ceremony of the changing of the guard at the Cabildo, across the Plaza de Mayo from the Casa Rosada.

andrewcusack.com: Argentina

Changing the Guard in Buenos Aires

The changing of the guard at Government House, Buenos Aires, the Presidential Palace of the Argentine Republic more popularly known as the ‘Casa Rosada’ due to its pink hue.

The Patricios regiment who provide the presidential escort were founded in 1806, making them as old as New York’s 7th Regiment. (Unlike the 7th, however, Los Patricios not only still exist but indeed flourish as the oldest regiment in the Argentine Army).

UPDATE: Cruz y Fierro corrects me that the presidential guard are formed by the Regiment of Horse Grenadiers, not Los Patricios. I have often confused the two in the past, I must admit.

andrewcusack.com: Argentina

A Lawyer’s Studio in Recoleta

This property in the Recoleta neighborhood of Buenos Aires was once a residential apartment until a multi-generational family of lawyers bought and transformed it into a law office. (more…)

Hipódromo Argentino de Palermo

THE PALERMO RACETRACK is the main center for equestrian events in Buenos Aires. It was first built in 1876. In 1908 the current main stand was built to the beaux-arts design of a French architect, Louis Faure Dujarric. The Argentine Grand National, a race of 2,500 meters, has been run here annually since 1885. (more…)

The Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires

Finest opera house of the New World

Am I old-fashioned, or aren’t footmen not supposed to smile?

This usher knows precisely how much (which is to say, how little) emotion to show.

But now, everyone to their seats…

The magnificent Teatro Colón is currently closed for refurbishment until 25 May 2008, when the most prominent opera house under the Southern Cross will reopen brighter and better than ever.

St. Alban’s College: 1907-2007

ASTUTE READERS OF the Buenos Aires Herald, itself over one hundred and thirty years old, would have noticed in the paid announcements section a week ago Sunday the following notification: (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories