Architecture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Wardour

The news from the West Country is that Jasper Conran OBE is selling up his place in Wiltshire, the principal apartment at Wardour Castle.

Wardour is one of the finest country houses in Britain, designed by James Paine with additions by Quarenghi of St Petersburg fame. It was built by the Arundells, a Cornish family of Norman origin, but after the death of the 16th and last Lord Arundell of Wardour the building was leased out and in 1961 became the home of Cranborne Chase School.

A friend who had the privilege of being educated there confirms that Conran’s assertion of Cranborne Chase being “a school akin to St Trinian’s” was correct, and tells wonderful stories of the girls’ misbehaviour.

Alas the modern world does not long suffer the existence of such pockets of resistance, and the school shut in 1990. The whole place was sold for under a million to a developer who turned it into a series of apartments, for the most part rather sensitively done, if a bit minimalist.

The real gem of Wardour, however, is the magnificent Catholic chapel which is owned by a separate trust and has been kept open as a place of worship. Richard Talbot (Lord Talbot of Malahide) chairs the trust and takes a keen interest in the chapel and the building. I was down there the Sunday the chapel re-opened for public worship after the lockdown and Richard was there making sure all was well.

Those interested in helping preserve this chapel for future generations can join the Friends of Wardour Chapel.

Corpus Christi

It seems silly to let today’s feast pass without mentioning Corpus Christi College at the University of Oxford. It’s one of the smaller colleges, with about 250 undergraduates and a hundred or so postgraduates studying in its charming quadrangles.

Founded in 1517, Erasmus hailed its library as inter praecipua decora Britanniae, “among the chief ornaments of Britain”, and Cardinal Pole — the last legitimate Archbishop of Canterbury — was a founding fellow.

More recently, John Keble became an undergraduate there in 1806, before accepting a fellowship at Oriel in 1811, and having Keble College founded and named after him a few years after his death in 1866.

Architecturally, Corpus’s most remarkable feature is the Pelican Sundial, which is actually a column dating from 1579 that contains twenty-seven different sundials. It was most recently restored in 2016, and copies exist at Princeton and Pomfret.

The terrace atop the new auditorium affords an excellent view of the former priory of St Frideswide, now used by the Protestants as Christ Church. (more…)

Onze Grootste President

The London Residence of President Martin van Buren

Transacting some business in March before the plague struck us here in London I found myself with a moment to spare and made a brief pilgrimage to No. 7, Stratford Place. It was in this handsome townhouse that Martin van Buren, the first New Yorker to ascend to the chief magistracy of the American Republic, had his residence when he served as the United States’s minister to Great Britain in 1831.

While I often claim that Calvin Coolidge was America’s greatest president in reality my chief devotion in that contest is to the Little Magician himself, the Red Fox of Kinderhook.

Among the many characteristics of this esteemed Knickerbocker is that English was not his native language and throughout his career as a democratically elected politician he spoke with a thick Dutch accent. To his wife, he spoke almost entirely in Dutch.

Jay Cost and Luke Thompson’s Constitutionally Speaking podcast at National Review recently released the first of a two episodes about van Buren and while I’m no fan of podcasts in general this was worth listening to.

One of the factors Cost and Thompson highlight is the utility of the party machine structures of the day in solidifying the practice of America’s democracy and acting as a vehicle of accountability, something too little appreciated by most later observers of the period.

We keen Kinderhookers and Van Buren Boys await the second instalment with anticipation.

Shamefully I have not yet made the pilgrimage to Kinderhook itself, but it’s pleasing to learn that the dominie of the Dutch Reformed Church is a graduate of the greatest university in the southern hemisphere.

A Chapel for Chernobyl

The Belarusian Church in London

Belarus was heavily affected by the disaster at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the neighbouring Ukraine back in 1986 when both countries were part of the Soviet Union. In the thirtieth anniversary year of that event, the Belarusian Catholic community in London dedicated a new chapel built to a striking modern design but evoking the folk churches of the old country.

Founded in 1947 as the White-Ruthenian Catholic Mission of the Byzantine-Slavonic Rite, the church grew out of the postwar migration to London of Belarusians who had served with the Polish army during the Second World War.

Succeeding the chapel of Sts Peter & Paul in Marian House, the new chapel is dedicated to St Cyril of Turau and All the Patron Saints of the Belarusian People.

In terms of church hierarchy, this mission is under the wing of the Ukrainian Catholic eparchy in Great Britain, part of the eastern-rite Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church which is in union with Rome. (more…)

Stave Churches

The category of the Stave Church is the only great Norwegian contribution to architecture.

Sigrid Undset attempts to explain why other contributions are scant:

As one of the most extensive and thinly settled countries in Europe, Norway possesses only a few architectural monuments.

There is a good reason for this.

In the Middle Ages Norway belonged to a united, Christian Europe. At that time art flourished here, though the artists themselves are nameless because their work was deeply rooted in the people. Their power of expression streamed from the people through them. This creative power left its imprint on us in the form of buildings and pictures, poems and music.

Then came the spiritual earthquake of the sixteenth century, the Renaissance and the Reformation. Norway was cut off. It became a land apart, and lost touch with the spiritual life of Europe. Much later our increasing world trade again brought us into contact with other countries.

Pester Lloyd, 1932

But at least we have the stave churches.

How Our Ancestors Built

The Hudson River Day Line Building in Albany

The visitor arriving at Albany, the capital of the Empire State, might be forgiven for presuming the riparian French gothic mock-chateau he first views is the most important building in town.

Built as the headquarters of the Delaware & Hudson, a canal company founded in 1823 that successfully transitioned into the railways, the chateau now houses the administration of the State University of New York. (Indeed, the Chancellor once had a suitably grandiose apartment in the southern tower.) That building, with its pinnacle topped by Halve Maen weathervane, is worthy of examination in its own right.

But next to this towering edifice is an altogether smaller charming little holdout: the ticket office of the Hudson River Day Line.

In the nineteenth century the Hudson River Valley was often known as “America’s Rhineland” and travel up and down the river was not just for business but also for the aesthetic-spiritual searching that inspired the Hudson River School of painters.

The Day Line’s origins date to 1826 when its founder Abraham van Santvoord began work as an agent for the New York Steam Navigation Company. Van Santvoord’s company merged with others under his son Alfred’s guidance in 1879 to form the Day Line. (more…)

The greatest church architect you’ve never heard of

The greatest church architect

you’ve never heard of

Ludwig Becker and His Churches

For such a prolific church architect of such high quality, not much is known about Ludwig Becker and, alas, he seems to be little studied. Born the son of the master craftsman and inspector of Cologne Cathedral, Becker had church building in his blood. He studied at the Technische Hochschule in Aachen from 1873 and trained as a stone mason as well.

In 1884 Becker moved to Mainz where he became a church architect and in 1909 he was appointed the head of works at Mainz Cathedral, a position he held until his death in 1940. His son Hugo followed him into the profession of church architecture.

That’s about all I can find out about Becker. But here are a selection of some of his churches, to get a sense of his agility in a wide variety of styles.

St Joseph, Speyer, is my favourite of Becker’s churches for the beautiful organic fluidity of its style. Here Art Nouveau, Gothic, and Baroque are mixed somehow without affectation. Rather enjoyably, it was built as a riposte to a nearby monumental Protestant church commemorating the Protestant Revolt. These two rival churches are the largest in the city after its famous cathedral. (more…)

Rashtrapati Bhavan

Debates rage in the trad community as to whether, in the context of India, it is more sound to support the Congress Party or to take some relief in the policies of Mr Modi and his Indian People’s Party (curiously always known in English as the BJP).

Presented with the choice of left-leaning instability with Congress or Hindutva-oriented instability with the BJP, one recalls Hofrat Kissinger’s comment about the Iran-Iraq War: “Isn’t it a shame they can’t both lose?”

But the recent visit to India of my fellow New Yorker, His Excellency the President of the United States, necessitated his calling in to one of the grandest residences of any head of state the world over: Rashtrapati Bhavan, the residence of the President of India.

Originally called Viceroy’s House, it was designed by Lutyens as the palace of one of the most powerful men on the face of the planet: the Viceroy of India.

But the building of this magnificent structure was an imperial swansong. Opened in 1931, just sixteen years later the subcontinent was partitioned, the Indian Empire and its Viceroy abolished. The Union of India took its place, with a Governor General instead of a Viceroy.

In 1950, this too was abolished as the Union became a republic, and the office of governor general was given a republican whitewash and renamed as President of India.

This head of state is not elected by the voters of the world’s largest democracy except indirectly through a combined college of the national parliament and the state legislative assemblies. Like a governor general, he does have some power but the real force lies in the prime minister — today Mr Modi.

Nevertheless, this building reflects the glory, power, and influence of one of the greatest nations of the earth.

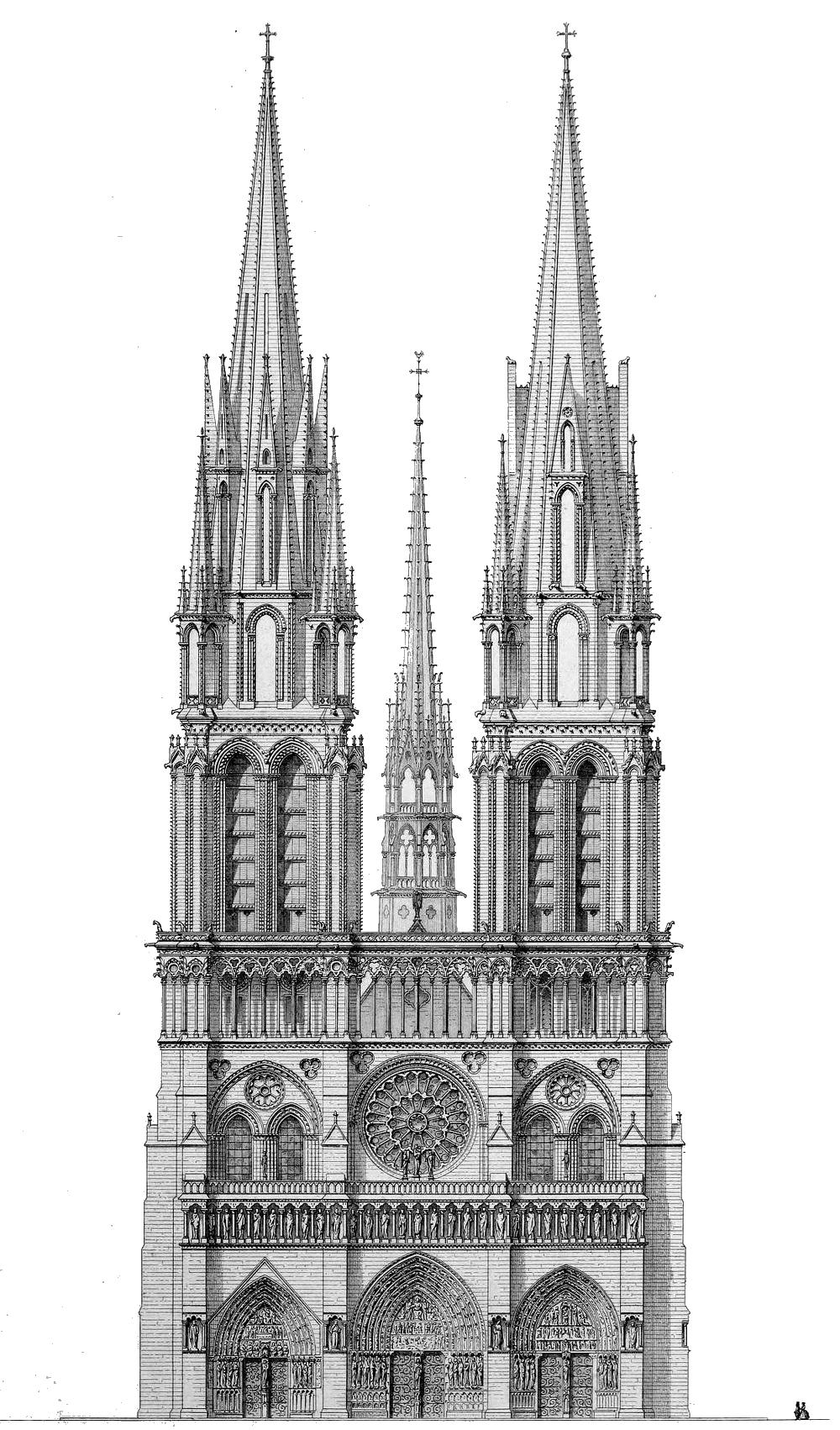

Notre-Dame de Paris

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

1844

A Corner in Camberwell

4a-6 Grove Lane by MATT Architecture

Alongside some of its neighbouring streets in Camberwell, Grove Lane has some of the best preserved rows of Georgian houses in south London, interspersed with a few buildings of a more recent vintage. The latest addition to this street is no ostentatious interloper but a contextual classic showing admirable humility and good manners.

Designed by Leicester Square-based MATT Architecture, it’s easy to see why the Georgian Group deemed 4a-6 Grove Lane worthy of a Giles Worsley Award for a New Building in a Georgian Context in 2015.

“The long, thin, wedge–shaped site had lain derelict for decades before being purchased by the current owner,” the architects note.

“The elevation is deliberately split into three to echo the plot width of neighbouring terraces and relies heavily on high quality detailing to lift it beyond pastiche.”

The Manor House

For devoted fanatics of Netherlandic architecture — I’m sure you’d count yourself as one as much as I do — a curious example of Dutch revival architecture can be found at No. 316 Green Lanes in the Borough of Hackney. Alighting from Manor House tube station the other day I was surprised to find myself confronted by a fine building which, it turns out, used to be the pub that gave its name to the Underground station.

The first ‘public house and tea-gardens’ of that name was built in the 1830s, and in 1843 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert stopped there for a change of horses. This tavern soldiered on until the arrival of the Piccadilly line which necessitated street widening and the demolition of the pub in 1930.

It was rebuilt in a very handsome brick Netherlandic revival in 1931 and continued on as a pub supplied by the London brewers Watneys.

A purist would object that the style of windows on the gables suggests a vulgar pakhuis (warehouse) on the Amstel while the stepped gable itself is more informed by domestic architecture. But is the privilege of architectural revivals to mix and match, so I don’t think we should complain.

Evidence suggests the pub shut in 2004 and the building was converted to its current retail use.

Alas, I can find no record of the architect, and the building remains un-listed, but I’m glad Hackney is home to this happy Hollandic interloper.

Haussmanhattan

Paris and New York are two cities radically different in design and character, but they are smashed together in this little project from architect Luis Fernandes.

‘Haussmanhattan’ is a portmanteau of Baron Haussmann, the Prefect of the Seine whose reconfiguration of the French capital made it the Paris we know today, and Manhattan, the most renowned of New York City’s five boroughs.

Haussmann’s plan of broad boulevards and radial avenues is a far cry from the artless Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 which created the unforgiving city blocks that colonised the entire island of Manhattan ad infinitum.

The contrast only makes the pick-and-mix Fernandes has confected all the more fun/ridiculous/interesting.

Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane still looms over the intervening centuries of architecture and design in Great Britain, but I’ve never actually known what he looked like. Apparently this is him, in an 1804 portrait by William Owen.

Everyone’s been to his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but Pitzhanger Manor, his place in the country (though Ealing hardly seems rural today) was recently reopened after serious conservation works ongoing since 2015.

Hope to pay it a visit soon.

Neo-Classical New York

The dome of the old Police Headquarters Centre Street in New York.

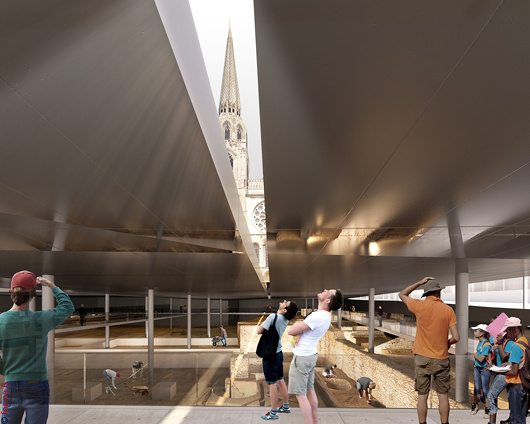

Chartres Disfigured

Plans for modern monstrosity in venerable cathedral’s forecourt

MORE BAD NEWS from Chartres. Fresh from the completion of a controversial and much criticised renovation of the ancient cathedral’s interior, le Salon Beige reports the city has unveiled plans to tear up the parvis in front of the cathedral and replace it with a modernist “interpretation centre”.

The original parvis (or forecourt) was much smaller than the one we know today. Between 1866 and 1905 the majority of the block of buildings in front of the cathedral, including most of the old Hôtel-Dieu, were demolished to give a wider view of the cathedral’s west façade and its “Royal Portals”.

After the war various plans to tart the place up were made and variously foundered — from a modest alignment of trees in the 1970s to Patrick Berger’s plan for an International Medieval Centre. More recently the gravelly space was unsuccessfully “improved” by the addition of boxes of shrubbery placed in a formation that, jarringly, fails to align with the portals of the cathedral.

The proposed “interpretation centre” designed by Michel Cantal-Dupart — at a projected cost of €23.5 million — destroys the gentle ascent to the cathedral and indeed reverses it. At a projected cost of €23.5 million, a giant slab juts apart as if displaced by an earthquake. The paying tourist is invited down into its infernal belly while others prat about on the slab’s upwardly angled roof, ideal for gawking at the newly commodified beauty of this medieval cathedral. It is practically designed for Instagramming, rather than reflection and contemplation.

As you would imagine, reaction has been strong. Michel Janva, writing at le Salon Beige, says the project “plans to imprison the cathedral” and “will disappoint not only pilgrims on their arrival, but also inhabitants and tourists”.

In the Tribune de l’Art, Didier Rykner is damning: “All this is purely and simply grotesque.” The sides of the centre, he points out, will be glazed to allow in natural light, but this will both interfere with multimedia displays and be bad for the conservation of fragile works of art. “This architecture, which looks vaguely like that of a parking lot, is frighteningly mediocre, and this in front of one of the most beautiful cathedrals of the world.”

Rykner attributes blame for the “megalomaniac and hollow project, expensive and stupid” at the doors of the mayor of Chartres, Jean-Pierre Gorges, who he argues has allowed much of the rest of the city’s artistic and architectural heritage to go to rot while devoting resources to this pharaonic endeavour.

Having walked from Paris to Chartres myself I can imagine how much this proposal will injure the experience for pilgrims. After three days on the road, to arrive at Chartres, stand in the parvis, and gaze up at this work of beauty, devotion, and love for the Blessed Virgin is a profound experience. If constructed, this plan would deprive at least a generation or two from having this experience. (But only a generation or two, for it is simply unimaginable to think this building will not be demolished in the fullness of time.)

Chartres is part of the patrimony of all Europe and one of the most important sites in the whole world. For it to be reduced to the plaything of some momentary mayor is a crime. With any luck, the good citizens of Chartres, of France, and of the world will put a stop to this monstrosity. (more…)

Happy New Year

The castle at Český Krumlov (or Krummau) in southern Bohemia, as photographed in winter by Libor Sváček.

Soho Iridescent

Stiff & Trevillion’s 40 Beak Street in London

Beak Street in London is teeming with turquoise iridescence since the completion of a new office building by the architectural firm of Stiff & Trevillion earlier this year. A joint project between property investment companies Landcap and Enstar, Number 40 Beak Street has been purchased for £40 million by Damien Hirst — the canny businessman who sells dead animals in formaldehyde glass boxes. The over-27,000-square-foot building will serve as the primary London studio for Hirst and headquarters for his company, Science (UK) Ltd, in addition to housing a restaurant at ground level.

Five storeys tall, 40 Beak Street features a number of roof terraces in addition to cornice work designed by Hertfordshire-based artist Lee Simmons. The glazed bricks — “hand dipped” the architects tell us — make for a welcome change from the omnipresence of metal and glass on one end of the spectrum and cheap monotone brick on the other.

The PR hype makes much of bringing a bit of artistic and creative edge back into Soho, a neighbourhood whose final glory days have been depicted in a much-praised book by the Telegraph’s Christopher Howse. We’re not so sure.

Hype aside, 40 Beak Street is an excellent addition to the London landscape and the designers are to be commended for their fine eye for detail. Someone at Stiff & Trevillion knows what they’re doing.

Holborn Town Hall

The Metropolitan Borough of Holborn was the smallest borough of London both in geography and population so perhaps it’s not surprising that its town hall was a pretty but rather humble affair. The civic pride and municipal pomposity for which this realm was once renowned are nowhere on show in this handsome building which, but for a few details, could easily be mistaken for a hotel, office building, or private residences.

Holborn Town Hall was built in stages, with the public library on the left-hand side completed in 1894 by the Holborn District Board of Works to a design by Isaacs. With the erection of the borough in 1900, a town hall was needed, and the central and right-hand sections of the building were added between 1906 and 1908 by the architects Hall & Warwick.

In 1965 the borough was merged with St Pancras to form the new London Borough of Camden. It was decided to consolidate the civic government at St Pancras Town Hall, to which the local government union members objected. To placate their ire, a bar for the use of employees was erected atop the annexe being added to the Camden (ex St Pancras) Town Hall — quickly nicknamed ‘the White Elephant bar’.

Though long sold off and converted into office space, the arms of the old borough of Holborn still grace the first floor balcony.

Knickerbocker Spires

Before the age of the skyscrapers, New York’s church spires dominated the horizon and dwarfed their neighbours just like in the medieval towns and cities of the old world — as this photo from the 1900s shows.

Here St Patrick’s Cathedral holds court, with the St. Nicholas Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church poking up a few blocks down Fifth Avenue.

Slightly north on that same boulevard sits the grand renaissance palazzo of the University Club, with the spire of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church poking up behind it.

Classical New England

A reminder that Russell Kirk once described the piano nobile of the Old State House in Hartford, Connecticut, as:

“perhaps the most finely proportioned rooms in all America”

Given the elegant restraint and classical detail of the old Senate chamber, it’s hard to disagree.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Image: © HughJLF

Image: © HughJLF Image: © Stephen Benton

Image: © Stephen Benton Image: © Stephen Benton

Image: © Stephen Benton