Architecture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Alys Beach

My list of favourite things starts with sunshine, good architecture, and the beach — Florida’s Alys Beach has all three. This is the third of the communities on the Gulf Coast designed by Duany Plater-Zyberk.

Their first, Seaside — well known as where ‘The Truman Show’ was filmed — is iconic but now feels a little sterile and over-planned. It has earned its place in the history books of urbanism and architecture regardless.

Rosemary Beach, their second development, was a vast improvement and based its architecture on the actual Spanish colonial styles used when the Cross of Burgundy flew over Florida rather than the more Mediterranean-influenced Spanish Colonial Revival of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Alys Beach is a splendid melange — a touch of the Cape Dutch, Bermuda here, the Maghreb there, and every now and then a hint of the French Caribbean. And it works: this is one of the most successful attempts at a beautiful and pleasing urban arrangement in twenty-first century America.

If any criticism can be issued it’s that Alys Beach is a holiday destination that will never be a “real” community where most people dwell all year round.

But if I was sitting en famille round a rooftop firepit watching the sun go down, I don’t think I’d complain.

St George’s Basilica, Prague Castle

A Home for Bard and Ballet

Sir Basil Spence’s unbuilt Notting Hill theatre

Sir Basil Spence was just about the last (first? only?) British modernist who was any good. His British Embassy in Rome is hated by some but combines a baroque grandeur appropriate to the Eternal City with the crisp brutalism of modernity that makes it true to its time.

In 1963, Spence accepted the commission from the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Ballet Rambert for a London venue to host the performances of both bodies.

The poet, playwright, and theatre manager Ashley Dukes had died in 1959, leaving a site across Ladbroke Road from his tiny Mercury Theatre (in which his wife Marie Rambert’s ballet company performed) for the building of a new hall.

The design moves from the sweeping curve of the street frontage up to a series of angular concoctions and finally the large fly-space above the stage itself.

It made the most of a highly constricted site and would have housed 1,100-1,600 patrons (historical sources vary on this figure). This was a big step up from the old Mercury Theatre which housed 150 at a push.

Ultimately, the plan failed. London County Council was worried there wasn’t enough parking in the area, and the Royal Shakespeare Company was tempted away by the City of London Corporation which was building the Barbican Centre.

New England Baroque

Above, the New England baroque of Dunster House, one of the residential colleges at Harvard.

Below, a simple boathouse built at the highwater mark on a New England beach.

Both images (c.f. here & here) from the blog of a twelfth-generation New Englander.

Liverpool’s Irvingite Church

The soi-disant “Catholic Apostolic Church” was one of the strangest but most fascinating Protestant sects the Victorian world brought forth. It was entirely novel — perhaps outright bizarre is a better description — in its combination of millenarian theology, evangelical preaching, and inventive ceremonialism. They were often referred to as Irvingites as a shorthand, owing to their origins amongst the followers of the Rev. Edward Irving, a Church of Scotland minister who led a congregation in Regent Square, London.

The Irvingites — after the death of Irving, it must be said — invented an elaborate hierarchy of twelve “apostles”, under whom served “angels”, “priests”, “elders”, “prophets”, “evangelists”, “pastors”, “deacons”, “sub-deacons”, “acolytes”, “singers”, and “door-keepers”. Coming from a very Protestant, low-church background, they curiously concocted elaborate liturgies influenced by Catholic, Greek, and Anglican forms of worship.

Another unique aspect of this group was its lack of denominational thinking: the Catholic Apostolic Church did not demand any strict or exclusive communion but was happy for its members and supporters to continue to be members of other churches or denominations.

One of the founding “apostles” of the Irvingite Church, Henry Drummond, married his daughter off to Algernon Percy, later the 6th Duke of Northumberland. That duke and his two immediate successors were known to be supporters of the Catholic Apostolic Church without disowning their established Anglican affiliation.

Despite this aristocratic land-owning connection, socially the Irvingite church spread most rapidly amongst the well-to-do mercantile classes, which meant they had congregations in places like Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool, Edinburgh, and even Hamburg. They were also very strict about tithing, which — combined with their mercantile status — meant they had a fair amount of money to spend on church building.

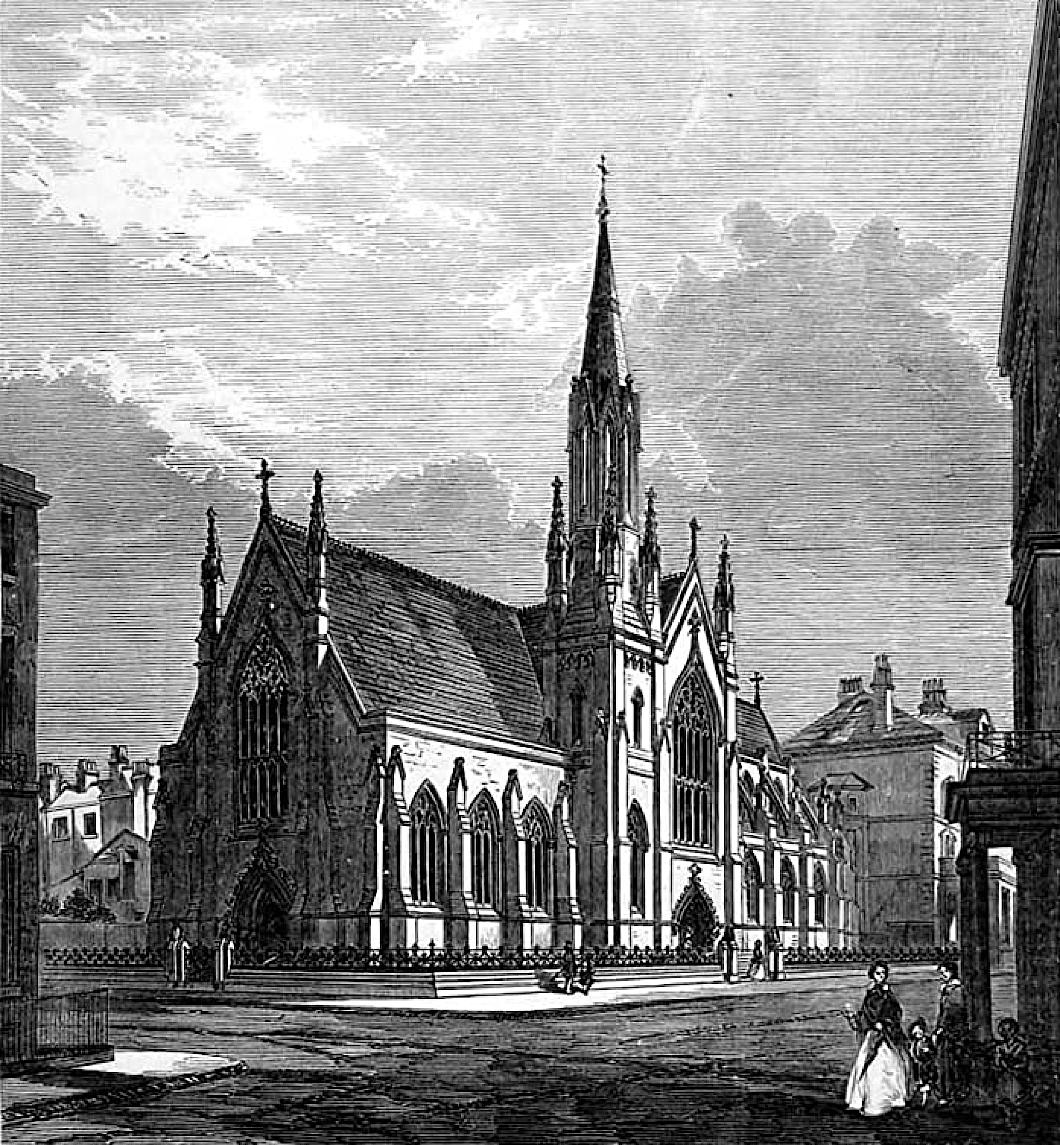

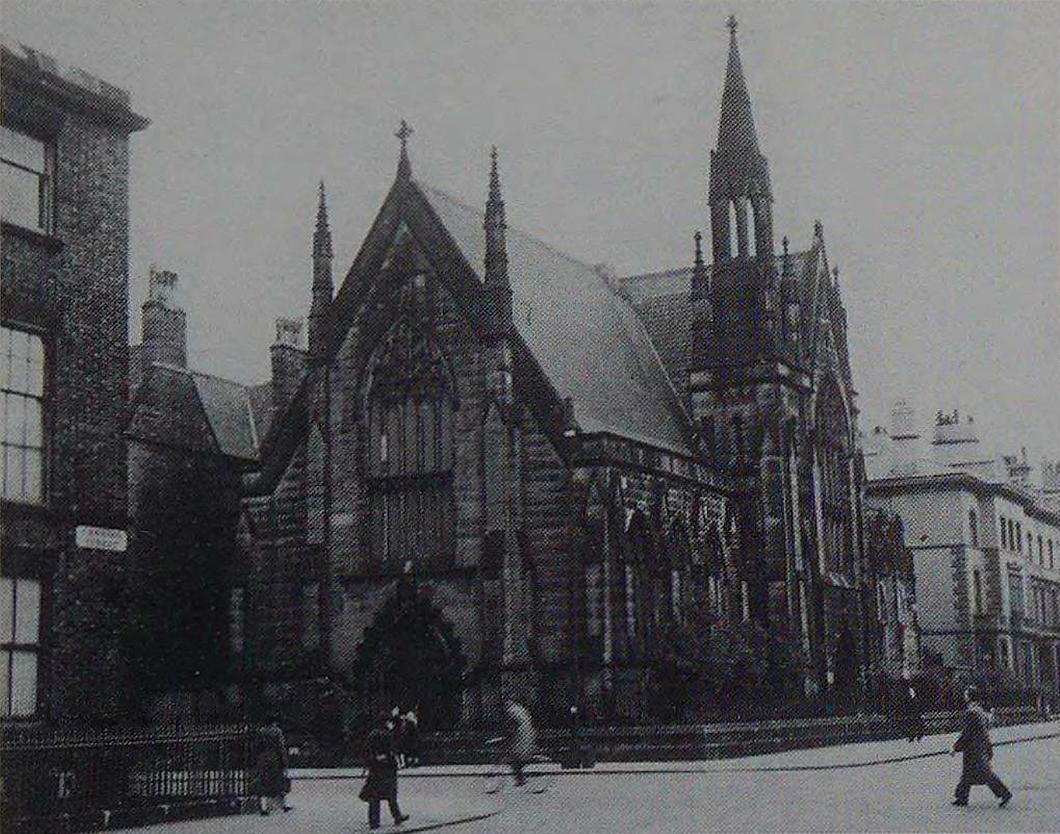

In Liverpool their church was built on the corner of Canning Street and Catherine Street in 1855-56. The design by architect Enoch Trevor Owen was influenced by Cologne Cathedral, with a nave more than 70 feet high.

Owen later moved to Dublin where he was employed as architect to the Board of Works, though he also designed the Catholic Apostolic Church in that city as well. (Today that building serves as Dublin’s Lutheran Church.) There’s some indication he designed the Catholic Apostolic Church in Manchester, so he might very well have been a member of the sect himself.

Another centrally important fact about the Irvingites: they didn’t believe that their original “apostles” could appoint further apostles. So when the last living “apostle” ordained his last “angel”, no further angels and so forth could be created. It endowed the clergy of this unique branch of Protestantism with an effective end date, but you have to give them credit for sticking with it. The last “apostle” died in 1901, the last “angel” in 1960, and their last “priest” in 1971.

Gone are all their elaborate inventive liturgies, and unsurprisingly the congregations have tended to fade away as well. The last clergy often recommended the lay people in their charge attend Church of England services when their own services stopped. The body continues to exist, and beside paying for the maintenance of its properties also makes annual grants to mostly Anglican but also Catholic and Eastern Orthodox bodies. In some very rare places, like Little Venice, prayer services are still held.

Indeed they still own their great central church in Gordon Square in Bloomsbury, though its chief use in the past decades has been being rented out first to an Anglican university chaplaincy, and now to the use of High-Church Anglicans as well as an Anglican evangelical mission.

In Liverpool their church was given Grade II listing protection in 1978, possibly when prayers services were still being held. By 1982 the church was up for sale, but without a buyer it succumbed to a fire in 1986.

The church lingered in ruins until the late 1990s when it was demolished and a nondescript block of flats erected on the site.

Elsewhere: Liverpool: Then and Now | Velvet Hummingbee

Watts Chapel

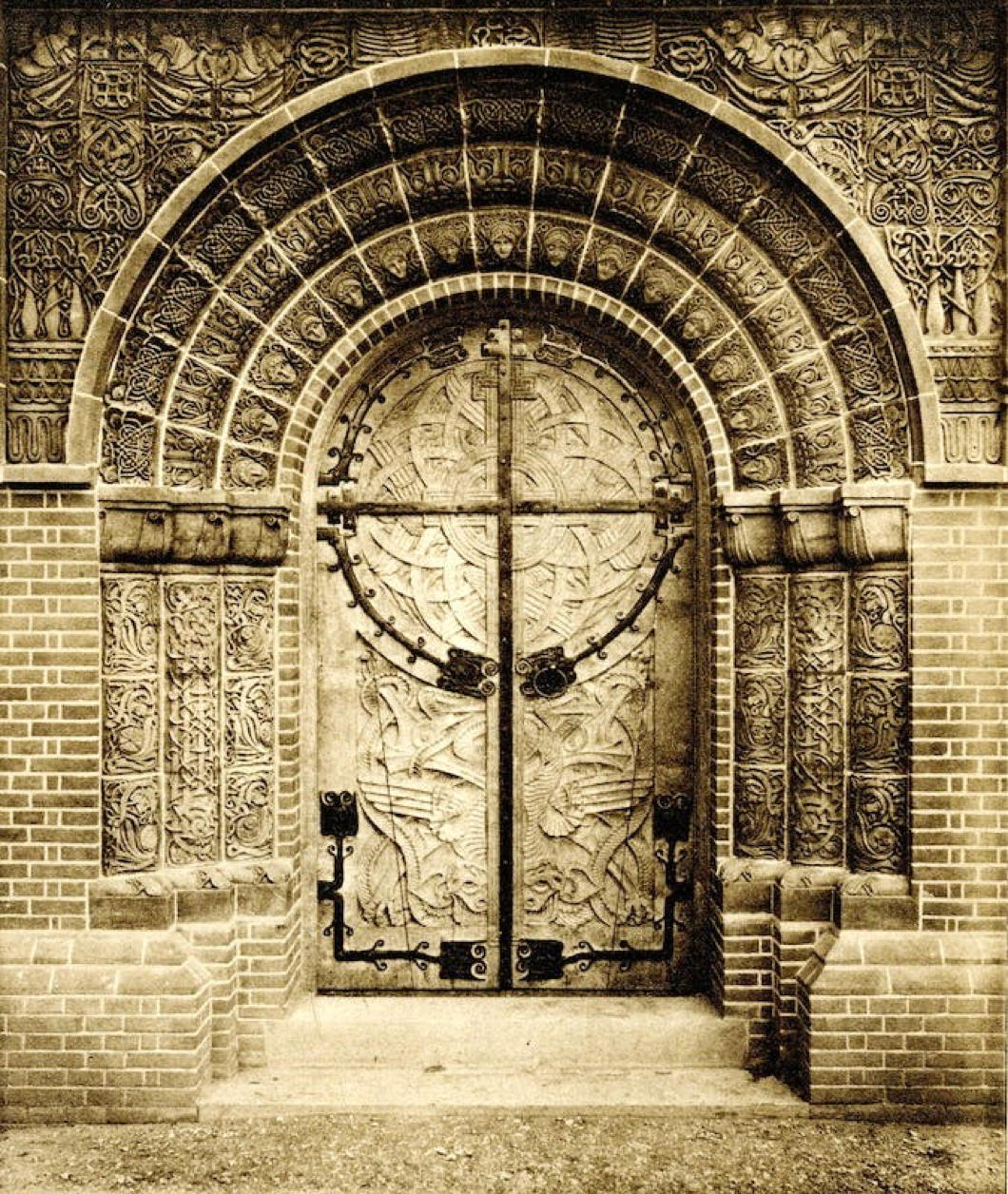

IS THIS the most beautiful door in England? The Watts Chapel in the village cemetery of Compton in Surrey is certainly one of the most remarkable buildings in the land.

I have to admit it completely escaped my notice until a friend of mine founded a distillery a few years ago and based the logo on the seraphs depicted within the chapel. While the interior is indescribable it is also curiously incapable of being captured by photography to any satisfactory degree.

Being a Celt with a Norman surname who loves the Romanesque, it’s the entry portal that captures my imagination. It beams at the very same frequency as my heart.

What a wonderful melange of elements — Celtic, Saxon, Romanesque, and Nordic — are combined here with blithe ease.

Incessant stylistic purity is the realm of the boorishly tiresome, as Ninian Comper knew well, and here the eclectic blend works well.

As architects are incapable of learning the proportion required by Georgian and neo-classical styles, I’ve long believed the Romanesque (or ‘Norman’ as the English often call it) must be the starting point for the recovery of good solid modern architecture.

I, for one, welcome our Norman-Romanesque future with open arms — while prizing this late Victorian gem.

Theodore Roosevelt

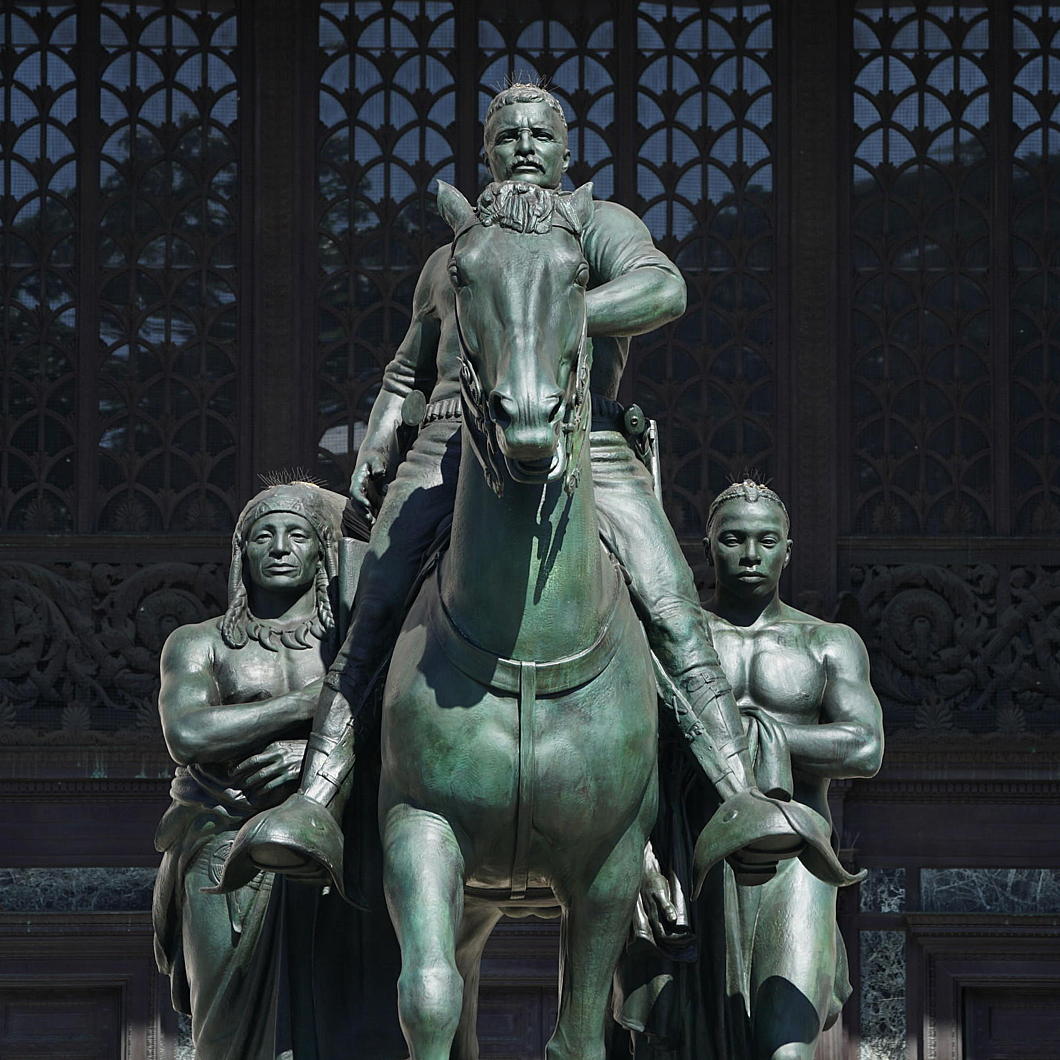

The ancient heresy of iconoclasm claimed a new victim this week: The statue of Theodore Roosevelt which graced the Manhattan memorial dedicated to him at the American Museum of Natural History has been removed at a cost of two million dollars.

The sculpture had attracted the ire of protestors who objected to the inclusion of a Native American and an African by the side of twenty-sixth President of the United States and sometime Governor of New York, which they claimed glorified colonialism and racism.

While the American Museum of Natural History is a private institution, it sits on land owned by the City, and the statue was paid for by the State.

The statue was doomed in June of last year when the New York City Public Design Commission voted unanimously to rip Teddy down.

As the New York Post put it, “He’s going on a rough ride!”

The statue was severed in two this week, with the top half removed and the bottom half following shortly after.

It will be shipped to the Badlands of North Dakota to be displayed as an object in a museum under construction there. (more…)

The Borough Synagogue

AS THE MOST ANCIENT of boroughs — and right across the bridge from the City of London itself — Southwark is presumed to have had at least a small Jewish community before the Edict of Expulsion in 1290. Records show the existence of a merchant and moneylender named ‘Isaac of Southwark’ who defended fellow Jews before the Exchequer of the Jews, the special court that dealt with Jewish taxes, fines, and legal cases.

Before 1290, it seems likely any Jews in the Borough would have crossed London Bridge to worship in the Great Synagogue in Old Jewry. After the Edict was rescinded in the seventeenth century, Jewish communities sprang up slowly. Pepys in his diary records a visit to the small Sephardic synagogue in Creechurch Lane in 1663, and by 1690 a new Great Synagogue had opened in the City for Ashkenazi Jews.

Jews in the Borough had their first known place of worship thanks to Mr Nathan Henry (born c. 1764). As a boy, Henry heard the mad Lord George Gordon speak in St George’s Fields (where your humble and obedient scribe is currently situated typing this) which provoked the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots. By a strange twist of fate, that Scottish nobleman ended up converting to Judaism and died in Newgate Prison styling himself Yisrael bar Avraham.

Around 1799, Nathan Henry fitted out a room as a synagogue in his house at No. 2, Market Street near the junction with Newington Causeway. (Market Street was later renamed Dantzic Street after the Baltic city, and is now Keyworth Street after a First World War winner of the Victoria Cross.) Later he roofed over the whole of the yard behind the house with entry gained through the shop at the front, and two rows of gallery seating above for ladies (entered through a bedroom).

Henry’s house-synagogue was small and crowded: it could fit a hundred people in uncomfortable circumstances, but those hundred were not always happy. The proprietor, having built the synagogue, considered himself the sole authority with the right to appoint wardens and office-holders. In 1823 a group of worshippers seceded and found new premises in which to worship in Prospect Place, the south side of what is now St George’s Road. The two synagogues continued in friendly relations and Nathan Henry was largely considered the head of the Jews of the Borough until his death in 1853, after which his house-synagogue shut up shop.

But by the 1860s the need for a new place of worship was apparent. For one thing, the lease on Prospect Place was coming up, and as Rabbi Rosenbaum put it the building was “incommodious, dilapidated, and unsightly, and was not even protection against inclement weather, for the roof admitted the rain and the raising of umbrellas during divine worship was no unusual occurrence”.

A building committee was put together, funds raised (more slowly than anticipated), and a site found in Albion Place, Walworth — soon to become Heygate Street. On 7 April 1867, the Borough New Synagogue was consecrated in a ceremony attended by almost all the Jewish clergy of London. In the evening, many of the congregation repaired to Radley’s Hotel in Bridge Street for a great big hooley to celebrate. The synagogue was accompanied by a boys’ school and a girls’ school both located next door. (more…)

From Buda towards Pest

A 1959 view from the Vienna gate of Budapest’s Castle district

Taken in 1959, a photograph in the Fortepan archive shows two girls standing on the stone bench of the Vienna Gate — rebuilt in 1936 to mark the two-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of Buda’s liberation from the Ottomans.

Hungary’s domed neogothic Parliament Building sits in Pest on the opposite bank of the Danube in the distance, with the baroque spire of the Church of the Wounds of St Francis nearer on the Buda side of the river.

Sadly, this fine view can no longer be seen: the trees in the park below the Bastion promenade have been allowed to grow too tall. A somewhat superfluous flagpole bears the banner of Budapest’s 1st District.

The Hungarian government has invested a great deal of care and attention (not to mention investment) to the Castle quarter in recent years, so perhaps restoring this view could be added to their to-do list.

The threat to Bevis Marks

The Spanish & Portuguese synagogue at Bevis Marks in the City of London is well worth a visit. The last time my parents were in town we went for a tour given by an ebullient guide who was a big fan of Ben Disraeli and who taught us the story of the congregation and the building.

In Apollo magazine, Sharman Kadish has written a good summary of the ongoing threat to Bevis Marks from proposed overbearing office developments. (Dr Kadish also wrote a 2004 article on “The ‘Cathedral Synagogues’ of England” in Jewish Historical Studies.)

One planning application which would have almost completely cut off the synagogue’s natural light has been rejected but others loom on the horizon, one recommended for approval by the City’s planning czars.

London blog ‘Ian Visits’ visited Bevis Marks in 2019.

The synagogue is now temporarily closed to visitors for renovations but shabbat services continue to take place. Visiting information otherwise can be found on the congregation’s website.

Incidentally — given that November is the month of the dead — the name carved above the entrance of the synagogue is Kahal Kadosh Sha’ar ha-Shamayim, or ‘Holy Congregation of the Gates of Heaven’ which mirrors the Catholic cemetery where two of my grandparents are buried. (more…)

Gut Wulfshagen

I love when a house is arranged with its farm buildings around a garth or a gaard or a hof.

At Gut Wolfshagen in Schleswig-Holstein the barns are arranged flanking a narrow pinch that gives just a hint of the manor house beyond, lending an air of baroque surprise.

This house was built by Andreas Pauli von Liliencron at the very end of the seventeenth century and was acquired by the von Qualen family in 1787.

When the last of the von Qualens here died childless in 1903 they bequeathed Gut Wulfshagen to the uxorial nephew Ludwig Graf zu Reventlow. (more…)

Northern Neogothic

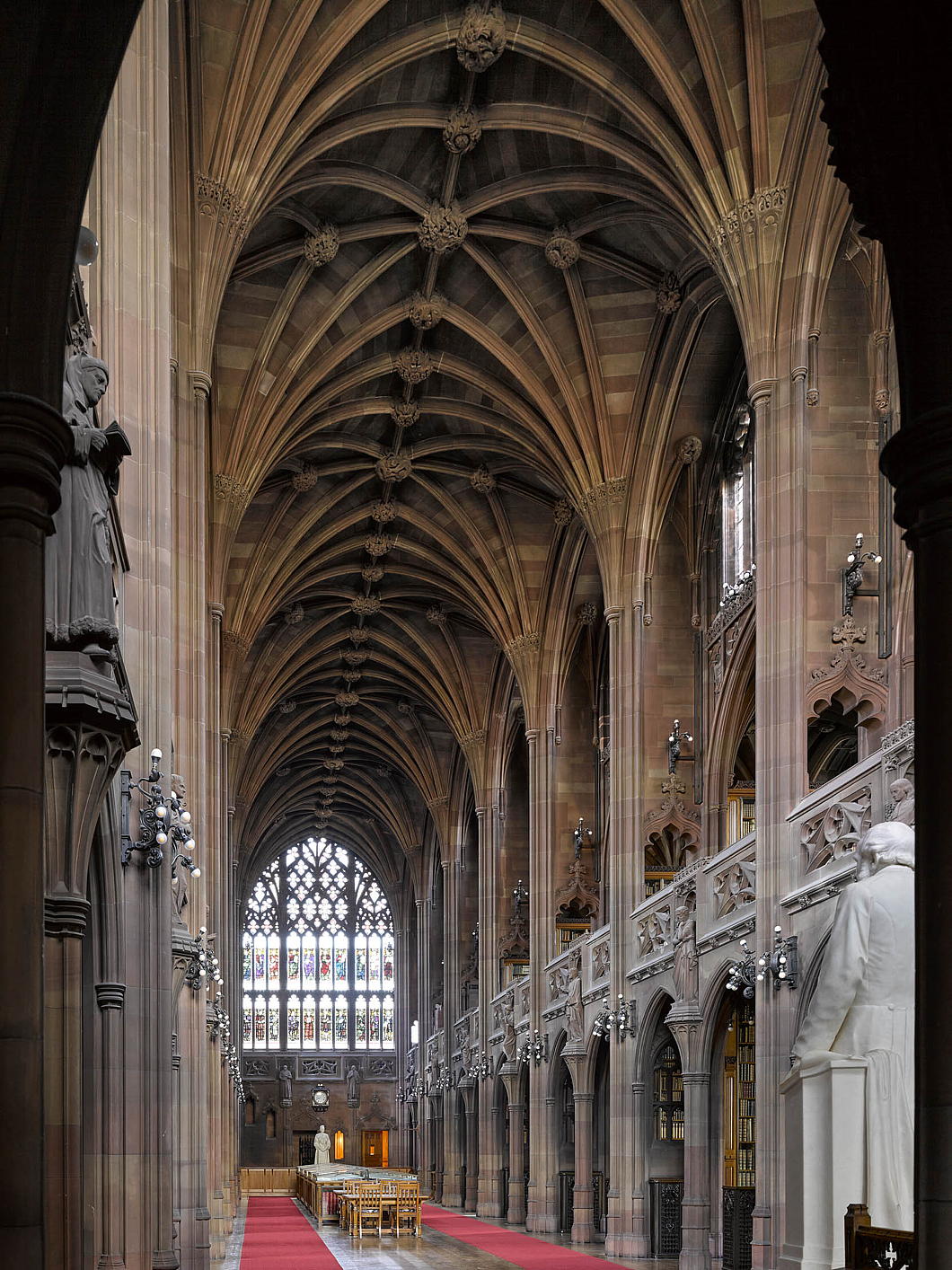

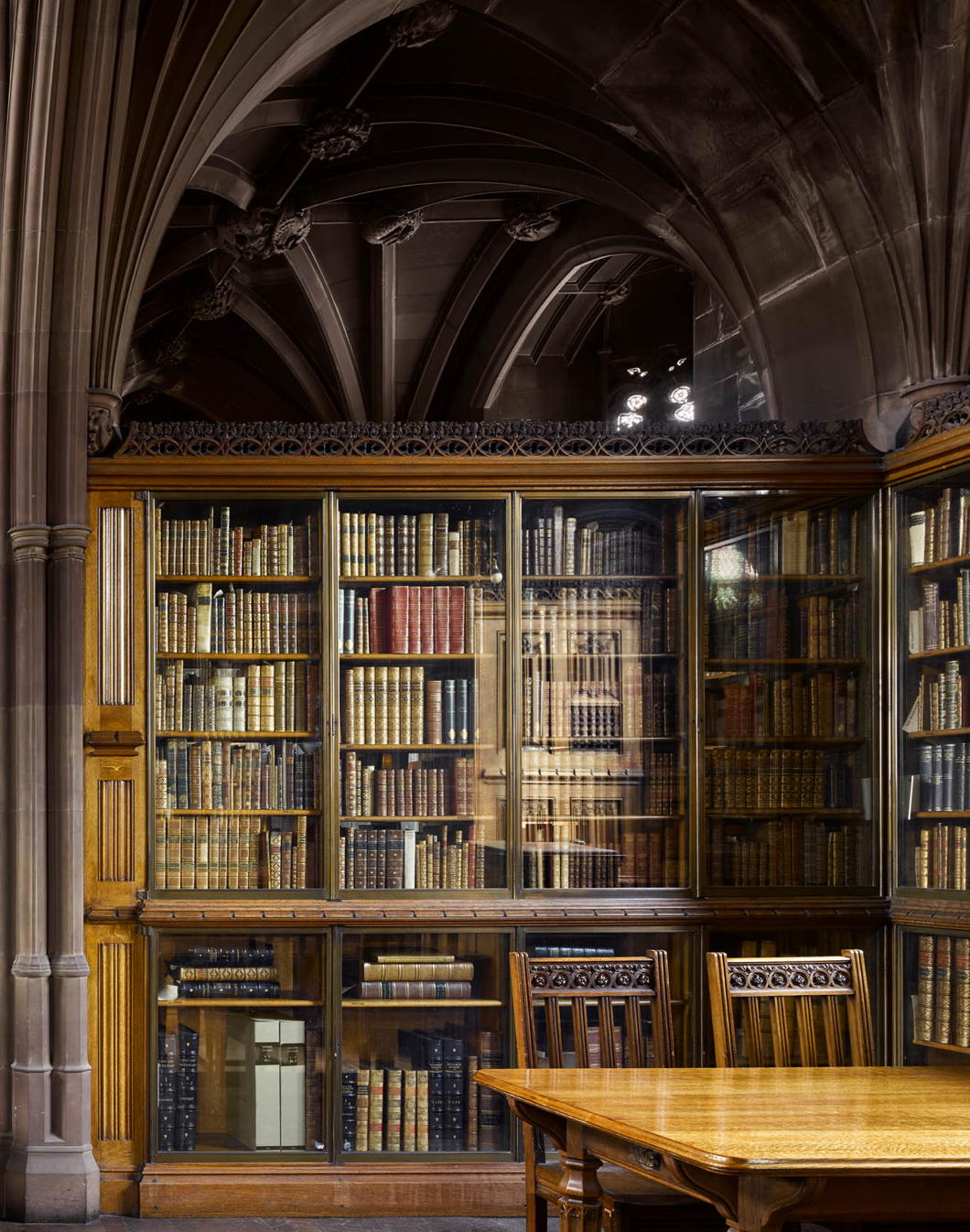

Will Pryce’s Photographs of the John Rylands Library

Will Pryce is one of the best architectural photographers out there and Country Life put him to good use for an article earlier this year about Manchester’s John Rylands Library.

The library was founded by the deliciously named Enriqueta Rylands in memory of her late husband, the merchant philanthropist John Rylands who became Manchester’s first multi-millionaire.

Manchester experienced a flowering of northern neogothicism in the nineteenth century, and the John Rylands Library is sometimes used as a film location standing in for Pugin’s Palace of Westminster, most recently in the 2017 film ‘Darkest Hour’. The city’s magnificent Town Hall fulfils this role even more often — c.f. the UK telly original of ‘House of Cards’. Scandalously, Manchester’s City Council no longer meet in their original council chamber, having decamped to the nonetheless handsome 1938 extension built next to it.

The John Rylands Library (and research institute) is here to stay though.

For more of Pryce’s work, see his website.

The old Dutch houses of the Cape

From Here There and Everywhere (1921) by Lord Frederic Hamilton:

THESE OLD DUTCH HOUSES are a constant puzzle to me. In most new countries the original white settlers content themselves with the most primitive kind of dwelling, for where there is so much work to be done the ornamental yields place to the necessary; but here, at the very extremity of the African continent, the Dutch pioneers created for themselves elaborate houses with admirable architectural details, houses recalling in some ways the chateaux of the Low Countries.

Where did they get the architects to design these buildings? Where did they find the trained craftsmen to execute the architects’ designs? Why did the settlers, struggling with the difficulties of an untamed wilderness, require such large and ornate dwellings? I have never heard any satisfactory answers to these questions.

Groot Constantia, originally the home of Simon Van der Stel, now the government wine-farm, and Morgenster, the home of Mrs. Van der Byl, would be beautiful buildings anywhere, but considering that they were both erected in the seventeenth century, in a land just emerging from barbarism seven thousand miles away from Europe, a land, too, where trained workmen must have been impossible to find, the very fact of their ever having come into existence at all leaves me in bewilderment.

These Colonial houses, most admirably adapted to a warm climate, correspond to nothing in Holland, or even in Java. They are nearly all built in the shape of an H, either standing upright or lying on its side, the connecting bar of the H being occupied by the dining-room. They all stand on stoeps or raised terraces; they are always one-storied and thatched, and owe much of their effect to their gables, their many-paned, teak-framed windows, and their solid teak outside shutters. Their white-washed, gabled fronts are ornamented with pilasters and decorative plaster-work, and these dignified, perfectly proportioned buildings seem in absolute harmony with their surroundings.

Still I cannot understand how they got erected, or why the original Dutch pioneers chose to house themselves in such lordly fashion. At Groot Constantia, which still retains its original furniture, the rooms are paved with black and white marble, and contain a wealth of great cabinets of the familiar Dutch type, of ebony mounted with silver, of stinkwood and brass, of oak and steel; one might be gazing at a Dutch interior by Jan Van de Meer, or by Peter de Hoogh, instead of at a room looking on to the Indian Ocean, and only eight miles distant from the Cape of Good Hope.

How did these elaborate works of art come there? The local legend is that they were copied by slave labour from imported Dutch models, but I cannot believe that untrained Hottentots can ever have developed the craftsmanship and skill necessary to produce these fine pieces of furniture.

I think it far more likely to be due to the influx of French Huguenot refugees in 1689, the Edict of Nantes having been revoked in 1685, the same year in which Simon Van der Stel began to build Groot Constantia. Wherever these French Huguenots settled they brought civilisation in their train, and proved a blessing to the country of their adoption. […]

Here, at the far-off Cape, the Huguenots settled in the valleys of the Drakenstein, of the Hottentot’s Holland, and at French Hoek; and they made the wilderness blossom, and transformed its barren spaces into smiling wheatfields and oak-shaded vineyards. They incidentally introduced the dialect of Dutch known as “The Taal,” for when the speaking of Dutch was made compulsory for them, they evolved a simplified form of the language more adapted to their French tongues.

I suspect, too, that the artistic impulse which produced the dignified Colonial houses, and built so beautiful a town as Stellenbosch (a name with most painful associations for many military officers whose memories go back twenty years ) must have come from the French.

Stellenbosch, with its two-hundred-year-old houses, their fronts rich with elaborate plaster scroll-work, all its streets shaded with avenues of giant oaks and watered by two clear streams, is such an inexplicable town to find in a new country, for it might have hundreds of years of tradition behind it!

Wherever they may have got it from, the artistic instinct of the old Cape Dutch is undeniable, for a hundred years after Van der Stel’s time they imported the French architect Thibault and the Dutch sculptor Anton Anreith. To Anreith is due the splendid sculptured pediment over the Constantia wine-house illustrating the stoiy of Ganymede, and all Thibault’s buildings have great distinction.

But still, being where they are, they are a perpetual surprise, for in a new country one does not expect such a high level of artistic achievement.

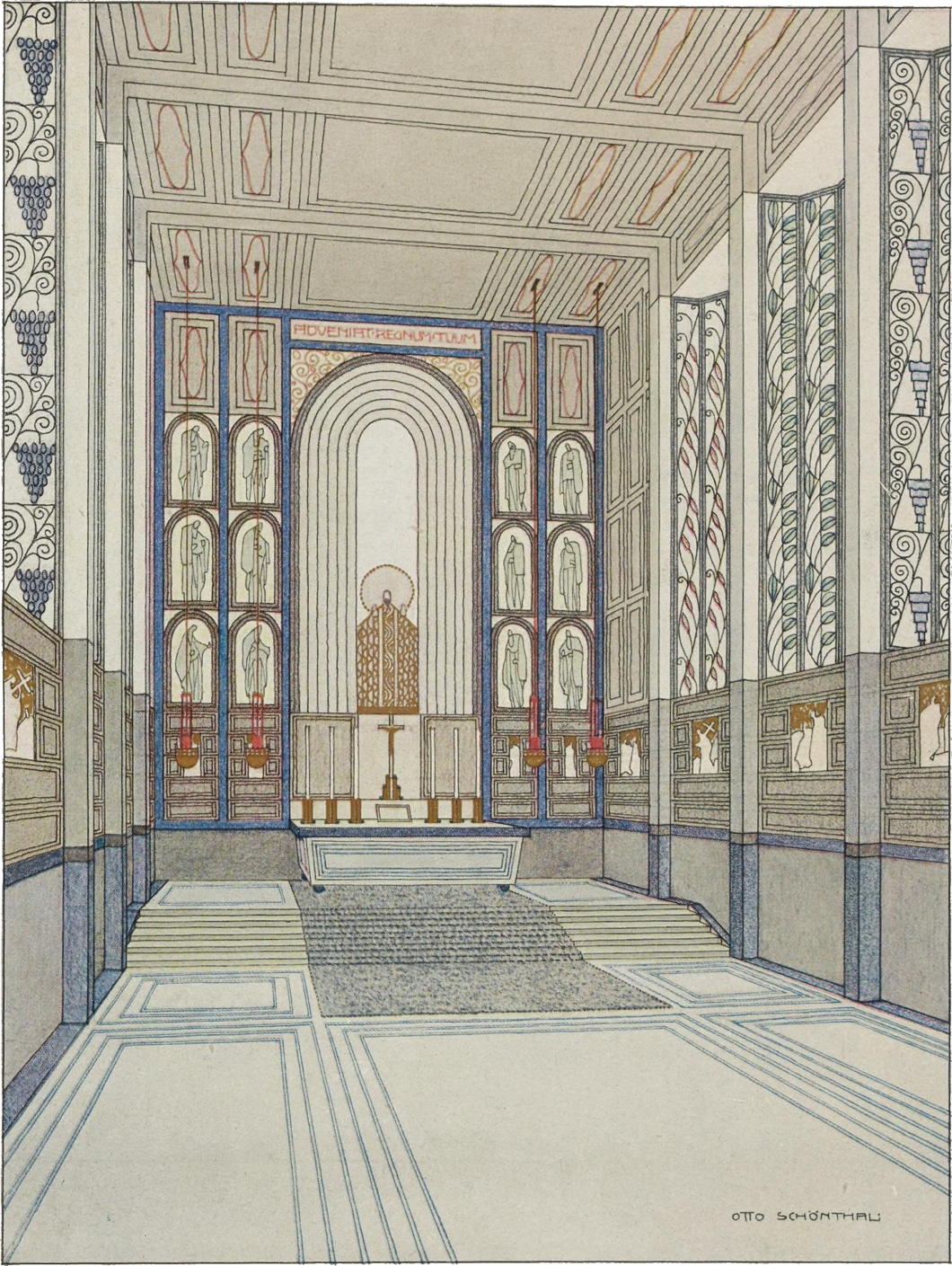

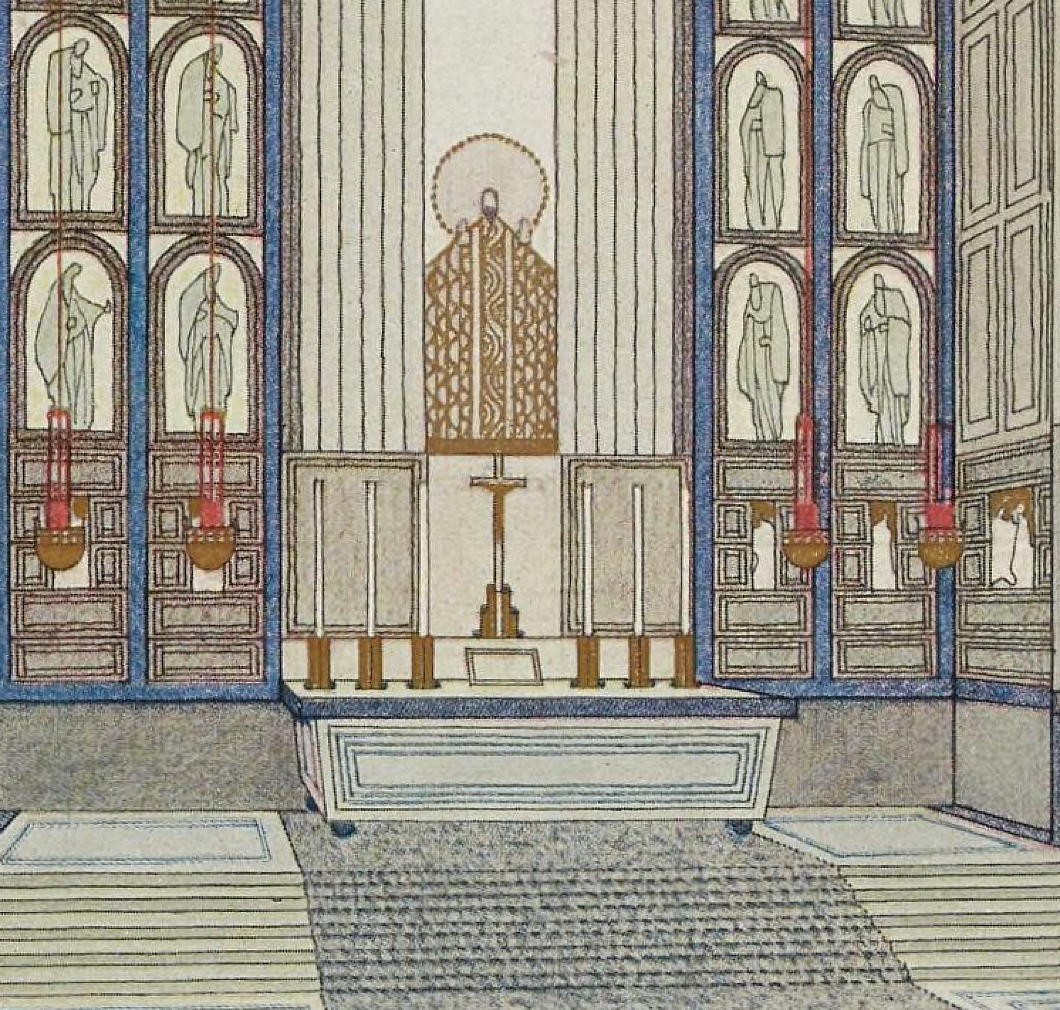

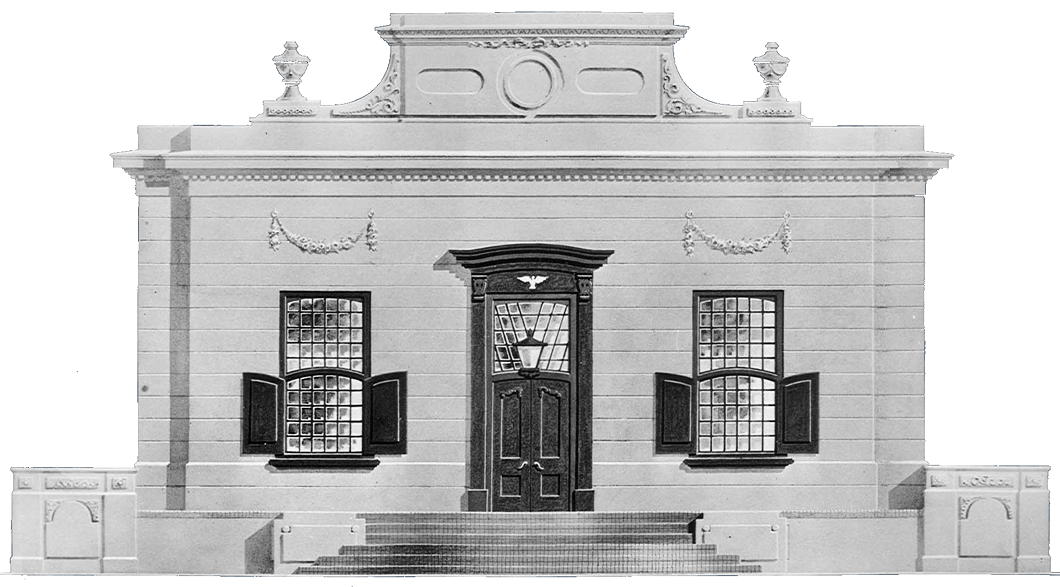

The Other Modern: Otto Schöntal

The Viennese architect Otto Schöntal was a student of Otto Wagner at the Academy of Fine Arts and exhibited this project for a Schloßkapelle in the periodical Moderne Bauformen in 1908.

It combines a simplicity of form with greater complexity in its decoration but like the work of many of the more mid-ranking architects of the Secession it comes across as a bit rigid and angular despite a certain freeness in its design.

A rood-stair pulpit

Among the features of the Church of All Saints in the Forest of Dean village of Staunton, Gloucestershire, is this fifteenth-century stone pulpit.

It is built into a rood-stair that once led to a wooden rood loft, demolished and removed some centuries ago.

This church also has a Norman font thought to have been hollowed out of an earlier square pagan Roman altar.

Pentonville Expressionism

When partner James Beazer of architectural firm Urban Mesh wanted to build an extension onto his Pentonville townhouse his tenderness towards brick expressionism took physical form.

“I love the work of the German Expressionists,” Beazer told the FT. “The playfulness of their use of brick. I think we’ve become uncomfortable with decoration today. Perhaps property has become too valuable. If it wasn’t, we’d all feel more able to take risks.”

Bringing brick expressionism down to a smaller scale produces interesting results here in Beazer’s case. It’s fun and somewhat slapdash — all the unconcerned confidence of an amateur delivered by a professional in his back garden. Hamburg meets the Shire in Islington.

I would have gently arched the windows, however, and the choice of lighting fixture is mundane. But it is a fundamental Cusackian principle never to let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

“I would probably have struggled to convince a client to do it,” Beazer says. But he has no confidence in the twisted brick add-on’s future once he moves house. “To be honest, the next people who move in will probably flatten it and replace it with a huge glass extension.”

The late Gavin Stamp gave an excellent lecture under the auspices of the Twentieth Century Society entitled ‘Hanseatic visions: brick architecture in northern Europe in the early twentieth century’.

It had been available online but now, alas, seems to be lost in the mists of time since the new incarnation of the Society’s website went up. Hope they stick it back online soon.

The Perfect Home Garage

The Coach-House at Saasveld, Cape Town

With all of Suburbia working from impromptu home offices set up in their garages during Covidtide — presumably clinging to their space heaters at this time of year — the subject of the residential garage came up in conversation.

America, being a land of plenty, has the very worst and the very best of home garages. The best are, if a separate structure, often in an arts-and-crafts style and ideally with a floor above perfect for extra storage, conversion to a rental unit, or space for disgruntled teenagers. If attached to the house itself, it is to the side, and only one storey, so as not to distract attention.

The worst, however, are double wide and take up most of the facade, as well documented by McMansion Hell.

My perfect residential garage, however, is not in the States but from the Western Cape. Saasveld was the home of Baron William Ferdinand van Reede van Oudtshoorn, also 8th Baron Hunsdon in the Peerage of England.

In the 1790s, the Baron built the house on his Cape Town estate — between today’s Mount Nelson Hotel and the Laerskool Jan van Riebeeck. The elegant house and outbuildings were almost certainly the work of Louis Michel Thibault, the greatest architect of the Cape Classical style.

Behind the house were two flanking wine cellars linked by a colonnade, at least one of which (above) was eventually put to use as a coach house or garage and photographed by Arthur Elliott.

Unfortunately the house and its grounds fell into ruin and the Dutch Reformed Church bought the site for development and decided to demolish Saasveld. Architectural elements from the house were preserved and eventually re-assembled at Franschhoek where a reconstructed Saasveld serves as the Huguenot Memorial Museum today.

As Mijnheer van der Galiën reports, however, the tomb of William Ferdinand is still at the original site.

Here in Franschhoek the matching wine-cellars-turned-coach-houses are reproduced with their linking colonnade. And I still can’t help but think that — so long as you could fit a Land Rover through the doors — they would make the perfect home garage.

A Scene in Buenos Aires

A hatted woman sits on a balcony, looking away out over the Plaza de Mayo, the Cathedral of Buenos Aires, and the city beyond.

It looks like the sort of thing taken by one of the French photographers, but in fact it is by a total amateur: Henry Dart Greene, the son of the Californian architect Henry Mather Greene (of Greene & Greene).

From 1928 to 1931, Dart Greene worked for the Argentine Fruit Distributors Company, founded by the Southern Railway to make use of the individual smallholdings long its line.

Upon his death, Dart Greene’s papers were deposited in the library of the University of California at Davis including this photograph from his time in Argentina.

While the building it’s taken from has been demolished and replaced with a bank, most of what you see beyond is still there.

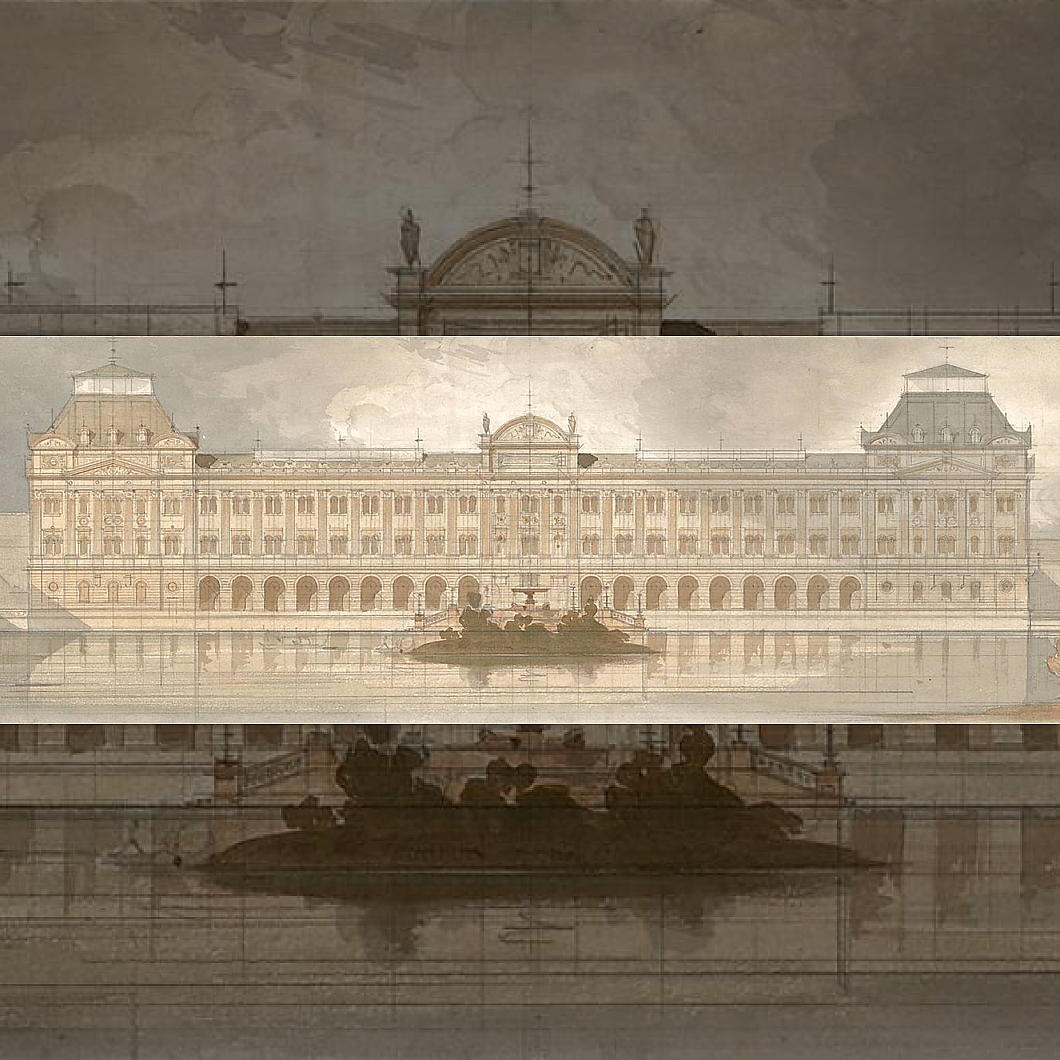

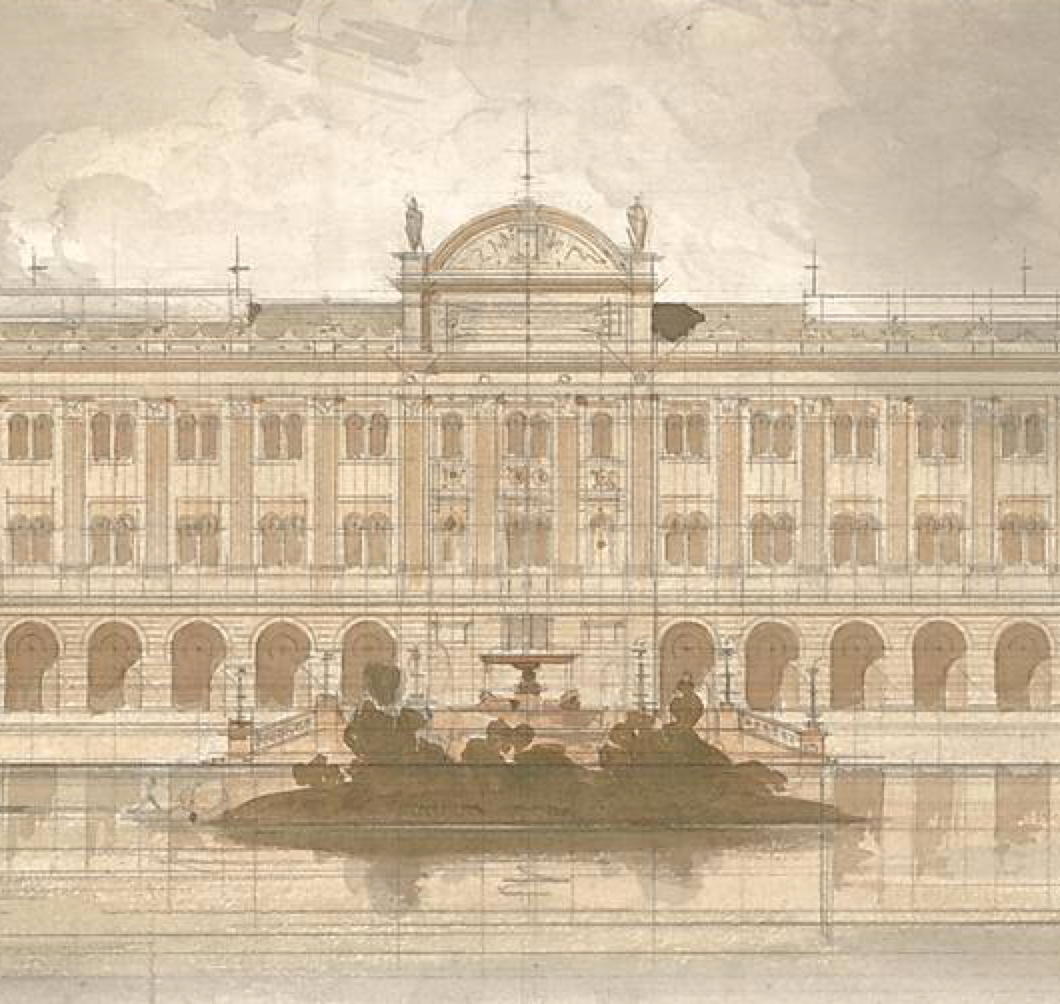

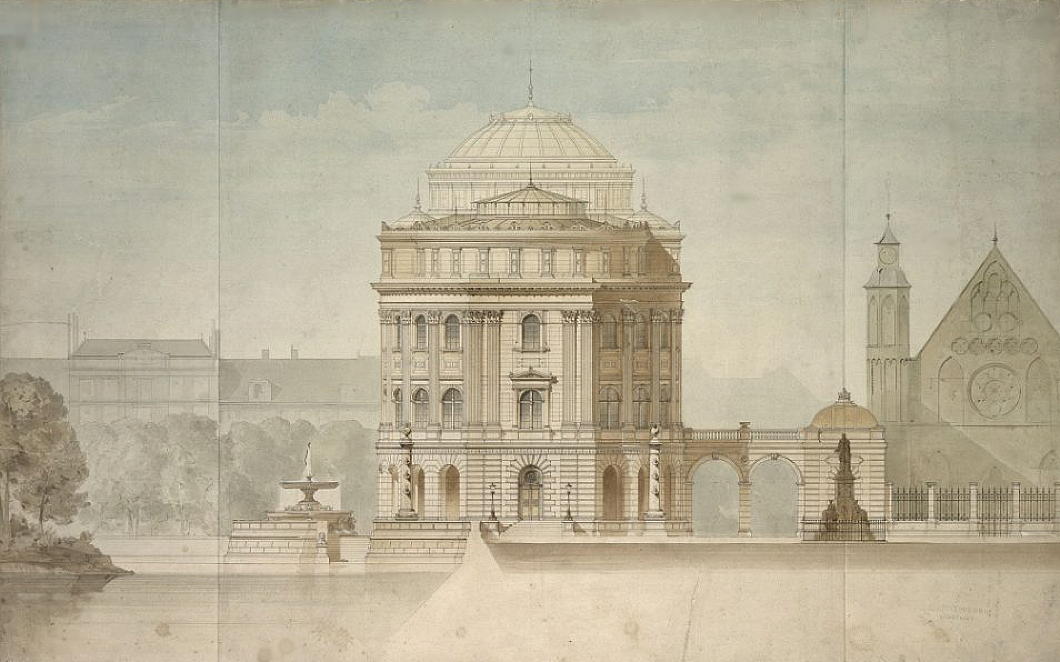

A Palace for the States-General

A Palace for the States-General

The nineteenth century was the great age for building parliaments. Westminster, Budapest, and Washington are the most memorable examples from this era, but numerous other examples great and small abound in Europe and beyond.

The States-General of the Netherlands missed out on this building trend, perhaps more surprisingly so given their cramped quarters in the Binnenhof palace of the Hague. The Senate was stuck in the plenary chamber of the States-Provincial of South Holland with whom it had to share, while the Tweede Kamer struggled with a cold, tight chamber with poor acoustics.

The liberal leader Johan Rudolph Thorbecke who pushed through the 1848 reforms to the Dutch constitution thought the newly empowered parliament deserved a building to match, and produced a design by Ludwig Lange of Bavaria. All the Binnenhof buildings on the Hofvijver side would be demolished and replaced by a great classical palace.

Despite members of parliament’s continual complaints about their working conditions, Thorbecke and Lange’s plans were vigorously and successfully opposed by conservatives. As the academic Diederik Smit has written,

A large part of the MPs was of the opinion that such an imposing and monumental palace did not fit well with the political situation in the Netherlands. […] In the case of housing the Dutch parliament, professionalism and modesty continued to be paramount, or so was the idea.

In fact, as Smit points out, significant alterations were made to the Binnenhof, like the demolition of the old Interior Ministry buildings by the Hofvijver, but these were replaced with structures that were actually quite historically convincing.

Further plans were drawn up in the 1920s — including a scheme by Berlage — but MPs felt that none of the proposals quite got things right and they were shelved accordingly. It wasn’t til the 1960s that the lack of space and the poor conditions in the lower chamber forced action. All the same, efficiency was the order of the day, as the speaker, Vondeling, made clear: “It is not the intention to create anything beautiful”.

Even then it wasn’t until the 1980s that the work was started, and the MPs moved into their new chamber in 1992. As you can see in this photograph, Vondeling’s aim of avoiding anything beautiful or showy has been achieved. The new chamber is certainly spacious — indeed some MPs claim it is too spacious. The art historian and D66 party leader Alexander Pechtold pointed out the distance between MPs inhibits real debate, unlike in the British House of Commons, and to that extent parliamentary design is inhibiting real democracy.

F.X. Velarde: Forgotten & Found

Many of the architects of the “other modern” in architecture were forgotten or at least neglected once the craft moved in a more avant-garde direction.

The British Expressionist architect F.X. Velarde who produced a number of Catholic churches in and around Liverpool in the interwar period and beyond is the subject of a new book from Dominic Wilkinson and Andrew Crompton.

There will be a free online lecture tomorrow on ‘The Churches of F. X. Velarde’ given by Mr Wilkinson, Principal Lecturer in Architecture Liverpool John Moores University. Further details are available here.

The book is available from Liverpool University Press with a 25% discount through the Twentieth Century Society. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories