Africa

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Dom Miguel de Castro

During the 1640s, a conflict arose between Kongo’s pious and militarily successful King Garcia II and his vassal, the Count of Sonho. Seeking the help of the Dutch Republic and its stadtholder, the Count sent his cousin, Dom Miguel de Castro, to the Netherlands as an emissary.

Dom Miguel arrived at Flushing in June 1643 and proceeded to Middelburg where he was received by the Zealand chamber of the Dutch West India Company.

During the Kongo nobleman’s fortnight in Middelburg, the chamber commissioned these portraits of Dom Miguel and his two servants painted by Jasper Becx — or possibly by his brother Jeronimus.

The Zealand chamber gave the trio of portraits to Johan Maurits — Prince of Nassau-Siegen, governor of Dutch Brazil, and originator of the Mauritshuis — who in 1654 gave them to Frederik III of Denmark, along with twenty Brazilian paintings by Albert Eckhout.

A full-length portrait of Dom Miguel was taken back to Africa by him and, alas, is now lost.

Dom Miguel de Castro

Jaspar Beckx, c. 1643;

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Dom Miguel de Castro

Jaspar Beckx, c. 1643;

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Articles of Note: 3.II.2022

“Lebanese money was worth more and there was more to eat when militias were fighting each other in the streets of Beirut 40 years ago than there is today.”

One of the great ironies of Lebanon’s current decline (Fernandez points out) is that, as destructive as the Civil War was, the country’s hopes were finally crushed by bankers and politicians rather than warlords.

— A bumper from The European Conservative: Tim Stanley says “Stay away from politics!” (I couldn’t agree less: we need brighter people involved!)

■ Idealists in Europe refusing to bow to reality have provided false hope to countries that have no real prospect of becoming members of NATO or the EU.

Damir Marusic muses on the Ukraine in How Not to Bend the Arc of History.

■ I ran into my friend João at a dinner party last night and he described the very existence of Brazil as “the greatest thing Portugal ever did”.

In 2018, Americas Quarterly claimed the now-deceased Olavo de Carvalho was the most important voice in Brazil’s then-incoming government (even though he didn’t live there).

More bizarrely fascinating is Nick Burns’s 2019 article on Bruno Tolentino, Carvalho, Ernesto Araújo, and the origins of the new Brazilian right.

Brazil’s foreign minister “penned an eyebrow-raising article for Bloomberg in which he blamed Ludwig Wittgenstein for Brazil’s debility on the world stage”.

If you’ve never lived in Latin America (I claim to have been at least partly educated there) you will never really understand quite how different it is.

■ When Algeria became independent, President Ben Bella had spent so long in French prisons that he had almost forgotten his Arabic.

One million French Algerians left within months, as American diplomats in Paris and Algiers at the time recall.

French Algerians “not only controlled the whole private sector, they had all the top government positions, and more importantly, they filled all the minor positions. The guy who read the gas meter in the utility company was a Frenchman. The women who worked the switchboard in the telephone company were all French. So the economy just came to a screeching halt.”

— Ex Africa semper aliquid novi: A new documentary (watchable online) explores Algeria under Vichy while another looks at Jacques Foccart, de Gaulle’s “Mister Africa”.

■ I am not much of a “Substack” aficionado, but I have recently given in and signed up to receive The Postliberal Order in my inbox. It’s penned by the quadrivirate of Vermeule, Deneen, Pappin, and Pecknold — all of whom have become household names in Cusackistan.

Patrick Deneen’s latest contribution on emerging postliberalism amidst the political persuasions of his students is worth a read.

Supermac and the Sarduana

Macmillan’s Attitude to Class and Race in the Late Empire

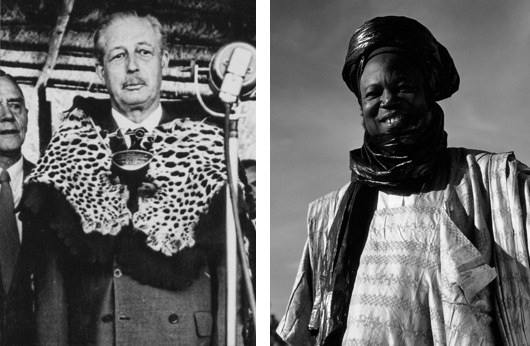

Left: Harold Macmillan touring Africa in 1960; Right: Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sarduana of Sokoto.

Staying over with some Kenyan friends in Wiltshire the other day, the old observation came up that, after the war, the officers settled in Kenya while the sergeants went to Rhodesia. While some of the leading lights of UDI had, in fact, been officers — Ian Smith an obvious case — it’s interesting to note that most of them came from humble backgrounds.

“Smithie” was born well-off in Rhodesia but his father had been a butcher’s son who went out to Africa and made good. Clifford Dupont, the first president of the Rhodesian republic, was born in London of poor East End Huguenot stock. His father had done well in the rag trade and got his son to Cambridge; Clifford became an artillery officer before emigrating to Africa.

Rhodesian Prime Minister Roy Welensky’s father was a Russian Jewish horse smuggler who married a ninth-generation Afrikaner. Roy was the couple’s thirteenth son, and left school at 14 to work on the railways and found success through the trade union movement.

Harold Macmillan, meanwhile, was a Guards officer and Old Etonian who had studied at Oxford. His famous ‘Wind of Change’ speech was just part of the British prime minister’s grand tour of Africa. “Supermac” started in Nigeria, where — unlike in some other parts of the continent — much of the native aristocracy had been preserved and coopted throughout colonial rule.

Proving Orwell’s observation that the English are the most class-ridden nation on earth, the PM felt comfortable amongst black African patricians in a way he couldn’t amongst members of the ruling white African elite from humble backgrounds.

In one of the ICBH’s oral history group discussions, Perry Worsthorne relates:

Somebody at some point has to mention, in any discussion of British politics, snobbery and class. I remember travelling and reporting on the ‘Wind of Change’ speech. We went to stay on the last bit, just before going on to Salisbury, was it the Sardauna of Sokoto who was he the premier of the Northern Nigerian region. Macmillan talked to us after he had seen him, he was flying on to Welensky the next day.

Macmillan used to have a sundowner with the correspondents covering his trip, and over whisky and sodas he told us how much more at home he felt with the Sardauna, who reminded him of the Duke of Argyll – ‘a kind of black highland chieftain’ – than he would feel in Salisbury as the guest of a former railwayman, Sir Roy Welensky. Snobbery, pure snobbery.

The British metropole was always ready to make racial distinctions and discriminate accordingly, yet it still tended to look upon outright racism with an air of disdain, as something slightly unsporting (or worse: foreign).

In the imperial periphery, racial attitudes amongst whites often differed greatly from Britain. This was most obviously so in South Africa, which for all intents and purposes embarked upon a radical revolutionary rejection of the British model of governance from 1948 with the implementation of apartheid. Rhodesia, needless to say, was another exception, if arguably more mild. “How different it would all have been,” Worsthorne somewhat patronisingly wondered, “if Ian Smith had been a gentleman.”

Meanwhile Nigeria’s Sir Ahmadu Bello — the Sarduana of Sokoto — was a statesman of cautious action, and his refusal to become Nigerian prime minister upon independence (he preferred sticking to his existing role as the powerful premier of the northern province) sadly deprived the federal state of the wisdom and experience which may have prevented its later descent into disarray. He was murdered by Major Nzeogwu during the 1966 coup d’état.

Differences of race or class aside, it’s telling that both the white low-born railwayman Welensky and the black patrician Bello ended up as knights of the realm.

Botswana and Hereditary Power

To any observer it must be obvious that hereditary power of some kind is natural and most of the time inescapable. It’s not that you need to be born into power to wield it, but experience shows it doesn’t hurt. Since I was born, there has been just one American presidential election (2012) in which a member of either the Bush or Clinton families was not either the official candidate of their respective party or a significant contender for that role.

In Canada, the current prime minister has sailed into office solely on a combination of good looks and being the son of a previous prime minister. In Ireland there are no fewer than forty-one families who have had three or more members elected to the Oireachtas (or to the Commons before it). The relatives and descendants of Timothy Sullivan managed to elect thirteen members between 1874 and 2016 as MPs, TDs, senators, or MEPs. Sullivan’s son and great-grandson both served as Chief Justice of Ireland to boot.

Sir Seretse Khama

Botswana — the most succesful state in Africa by many gauges — today celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of its assuming the mantle of sovereignty after eighty-one years as a British protectorate. Given that the United States, Canada, and Ireland are generally viewed as succesful countries, the hereditary aspect of power might help explain the comparitive success of Botswana, a multiparty state with free and fair elections, relative to its neighbours. The fourth and current president is Ian Khama, formerly a lieutenant general in the Botswana Defence Force. President Khama is the son of Sir Seretse Khama, the Balliol man who led his country and its people to independence fifty years ago and served as Botswana’s first president. Sir Seretse in turn is the grandson of King Khama III, last kgosi of Bechuanaland before the protectorate and leader of the Bamangwato tribe.

When Sir Seretse Khama became leader of Botswana it was the third poorest country in Africa — now it is the sixth richest on the continent in terms of GDP per capita. In a continent not known for good government Botswana, though not without its problems, is an oasis of stability and order.

At today’s celebrations for the fiftieth year of independence, President Khama wasn’t taking any credit for his country’s success: “Where we may have failed we take the blame. Where we succeeded we thank God.”

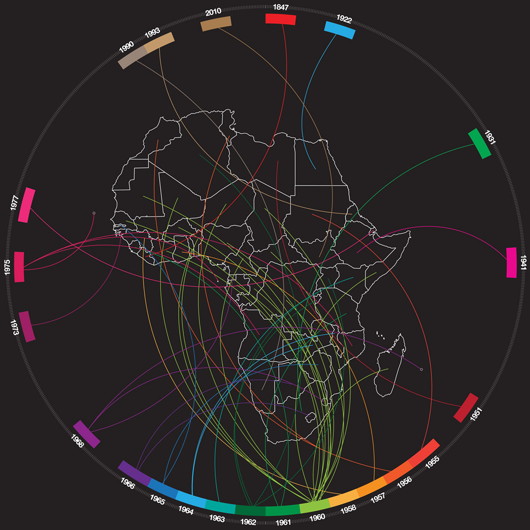

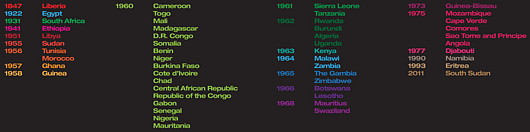

African Independence

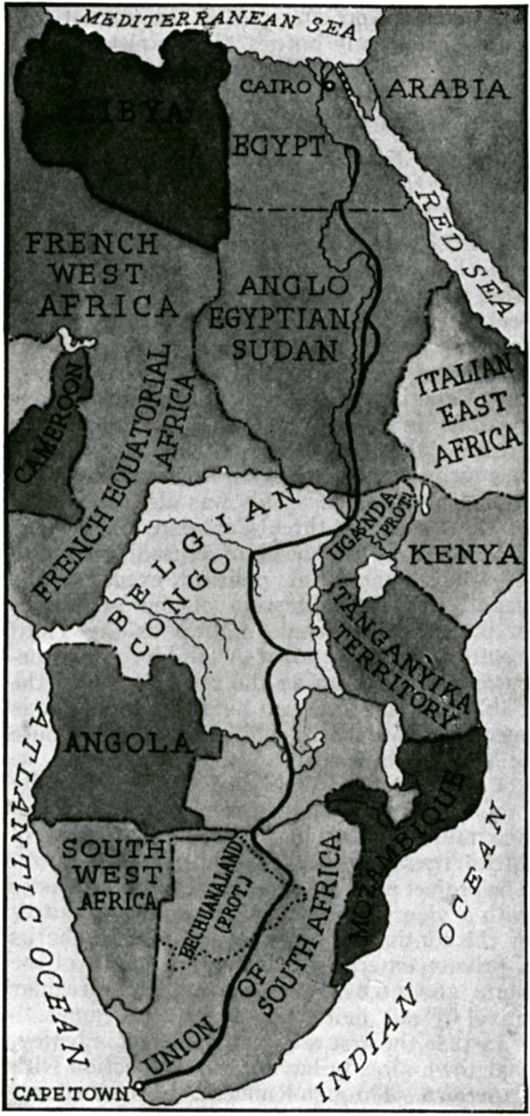

The nifty ‘Tumblr’ site Afrographique, which Africa-related facts and statistics in a visually appealing and accessible way, created a handy chart of all the countries of Africa and the years they became independent. The chart correctly gives Zimbabwe’s date of independence as 1965, even though it had a brief return to colonial status for a few months in 1979-1980. Yet it lists Ethiopia’s “independence” year as 1941, despite the fact that Ethiopia has arguably been independent forever.

The Empire of Ethiopia was founded in 1137 with the ascent of the Zagwe dynasty (responsible for the country’s world-famous rock-hewn churches), and while it was occupied by the Kingdom of Italy (whose monarch usurped the title ‘Emperor of Abyssinia’) from 1936 to 1941 with a continued insurgency and a lack of abdication by the legitimate emperor, Haile Selassie, there’s a strong case that Ethiopia retained her independence throughout but merely suffered a temporary foreign occupation.

Despite this arguable discrepancy it’s not nearly so bad as Africa Report, which published a chart claiming that South Africa gained its independence in 1994. Pray tell, what colonial power ran South Africa before 1994? South Africa was unified and gained dominion status in 1910, and Afrographique goes for the much safer independence date of 1931 when the Statute of Westminster was adopted asserting the sovereignty of the dominions of the British Empire. Some Afrikaners claim South Africa did not become independent until the Republic was declared in 1961, but this is neither legally nor constitutionally the case as the country as an internationally recognised sovereign independent nation merely changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic.

Afrographique has a number of other interesting posts, including African Nobel Prize winners (nine of them South African, across medicine, peace, and literature) and the ten richest Africans (fellow Matie Johann Rupert is #4).

An “Unknown Delegate”?!?!?

It’s Bilderberg  season again, which normally has all the conspiracy theorists this side of Roswell up in a flurry. This year, however, the organisers have cheated by having a website and even a press release concerning the proceedings. The Guardian has a photo gallery of the various guests arriving, mostly attired in the tiresome suit-but-no-tie combination which has become all too prevalent of late.

season again, which normally has all the conspiracy theorists this side of Roswell up in a flurry. This year, however, the organisers have cheated by having a website and even a press release concerning the proceedings. The Guardian has a photo gallery of the various guests arriving, mostly attired in the tiresome suit-but-no-tie combination which has become all too prevalent of late.

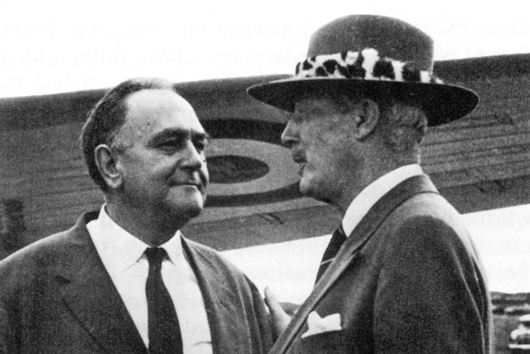

The super-trendy left-wing newspaper, however, demonstrates its typically Euro-centric mindset through its caption for this photo: “Francisco Pinto Balsemão, a former prime minister of Portugal and the CEO of Impresa, says goodbye to an unknown delegate.” An “unknown delegate”?!?!? That’s no less than Dambisa Moyo, the most famous Zambian in the world (referred to as “our girl” in Zambian newspapers), not to mention author of a New York Times bestseller and African star-of-the-hour for over a year now. Honestly, Mr. Guardian!

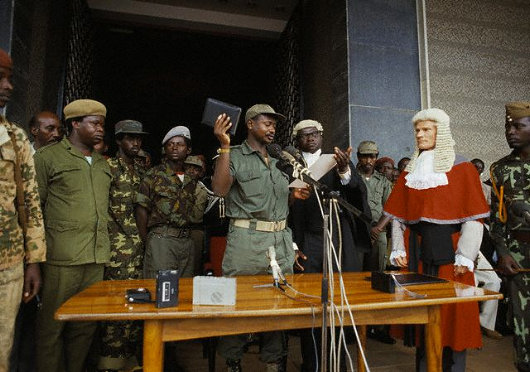

The Informal and the Formal

I can’t help but be amused by the brash contrast of the informal and the formal in this photo of Yoweri Museveni’s inauguration as President of Uganda in 1986. The years after Idi Amin’s overthrow in 1979 were almost as turbulent as the rule of the alleged cannibal. Milton Obote, the man Idi Amin had overthrown to gain power, returned to the presidency for five years during which Uganda’s troubles never ceased. In January 1986, the Obote government collapsed after Museveni’s rebel army seized the capital. The old emperor had fled, and the apparatus of state hailed the new emperor as their own. Museveni, Holy Writ in hand and guided by a clerk as the Chief Justice looked on, took the oath of office and formally ascended to the presidency of the nation. (more…)

Of tribes and traditions

In tribal Africa, Ghaddafi expounds traditional government; Meanwhile ethnic Romanians vote to be ruled by their German neighbours.

«Ghaddafi dreams of kings, princes, sultans, sheiks»

reports the Afrikaans newspaper Die Burger.

ONE OF THE LESS-REPORTED aspects of the selection of Col. Moammar al-Ghaddafi, the tent-dwelling Libyan leader and notorious eccentric, as Chairman of the African Union was his proposal that an upper house of “kings, princes, sultans, sheiks, and other traditional leaders” be added to the Pan-African Parliament. Col. Ghaddafi has been forthright in his condemnation of democracy as ill-suited to the African continent. “We don’t have any political structures [in Africa], our structures are social,” he explained to the press. Africa is essentially tribal, the argument goes, and as such multi-party democracy always develops along tribal lines, which eventually leads to tribal conflict and warfare. “That is what has led to bloodshed,” the AU chairman posited, citing the recent example of the Kenyan elections.

Europe, of course, solved the matter of tribal difficulties by brutally uprooting long-established peoples from their native lands after the Second World War and transferring them to jurisdictions in which they would ostensibly be part, not only of the majority, but of theoretically “national” states. Cities with centuries of Polish history became Soviet, towns as German as sauerkraut became Polish, and so on and so forth. Sometimes the undesired populations of multi-ethnic places were cruelly murdered, as recent revelations from the police in Bohemia have shown.

Still, remnants of the old cosmopolitan order remain. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories