Cape Town

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The National Assembly

Despite the longer history behind the original wing of South Africa’s Parliament House, when most people think of Parliament today they think of the 1983 wing that currently houses the National Assembly. The wing was designed by the architects Jack van der Lecq and Hannes Meiring in a Cape neo-classical style similar to the rest of the building, and it is actually quite a handsome composition despite the awkwardly proportioned portico, which is too tall for its width or two narrow for its height. (more…)

Rouwkoop: An Old Cape Hodgepodge

We can deduce a lot about a power by looking at the structures it erects. The return to neo-classicism under Stalin after the earlier Russian deconstructivist architecture of the 1920s is telling, as is the almost universal (and only seemingly contradictory) adoption of socialist Bauhaus architecture for the headquarters of New York corporations in the post-war period, or the turn to Brutalism by the governments of numerous Western liberal countries in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. While the apartheid government adopted a guise of conservatism, its revolutionary re-ordering of South African society was so radical that, for example, the old Edwardian railway station in Cape Town was demolished and completely rebuilt in order to better accommodate the separation of the races.

When the Afrikaner Nationalist government was elected in 1948, it inherited one of the richest architectural traditions in the world. South African architecture, from the original Cape Dutch so praised by Ruskin, through the Cape Classical of the architect Thibault and the sculptor Anreith, and on to the attempt at a South African national style by Edwardian architects like Herbert Baker, the nation’s legacy of boukuns (building-art) is one of which any nation would be proud.

The Cape Dutch style has proved particularly versatile and easily reinterpreted in almost every age of South African history since Jan van Riebeeck planted the oranje-blanje-blou on these shores in 1652. Yet from 1948 until its final electoral demise in 1994 the National Party government erected almost no buildings in the “national style” of Cape Dutch or its aesthetic descendants. Instead, they built in the grim modernist style found everywhere else in the world, both in the liberal-capitalist West and the totalitarian-Marxist East. One need only consider the Nico Malan (now Artscape) in Cape Town, the Staatsteater in Pretoria, or the Theo van Wijk building at Unisa. (more…)

’n Indiese woning in die Moederstad

Kaapstad het ’n bietjie van die Himalajas

Twee versamelaars van suid-Asiatiese kuns het ’n subkontinentale woning in ’n Kaapstadse meenthuis geskep. Die huis was die onderwerp van ’n artikel deur Johan van Zyl in ’n onlangse uitgawe van Visi-tydskrif met hierdie foto’s van Mark Williams. Die algehele effek is ’n bietjie “over the top” vir my, maar die verleiding van die Oriënt sal nooit ophou. (Bo: ’n Paar van marmer-olifante uit Udaipur wagte by die hoofingang).

“In ’n nou keisteenstraat aan die rand van die Kaapse middestad staan ’n huis met ‘n geskiedenis” Mnr van Zyl skryf. “Toe dit in 1830 vir Britse soldate gebou is, het die branders nog digby die voordeur geklots, en nie lank daarna nie het Lady Anne Barnard hier sit en peusel aan ’n geilsoet vy wat ’n slaaf vir haar gepluk het, stellig van dieselfde boom wat nou in die huis se (nuwe) trippelvolume-glashart staan, ’n knewel met ’n vol lewe agter die blad.”

“’n Dekade of twee gelede het die reeds luisterryke geskiedenis van die huis ’n eksotiese dimensie bygekry toe twee toegewyde versamelaars — selferkende stadsjapies wat destyds in die modebedryf werksaam was — hier kom nesskop met hulle groeiende versameling Indiese oudhede.” (more…)

An Old Dutch Holdout

The sign on the façade of No. 7 Wale Street, Cape Town in this 1891 photo informs us of its status as a police station in the two official languages of the day, English and Dutch, not Afrikaans. ‘Politie’ is the Dutch word for Police, while the Afrikaans is ‘Polisie’. Afrikaans only became an official language of South Africa in 1925, but was so alongside Dutch and English until 1961, when Dutch was finally dropped.

This beautiful old Dutch townhouse, with its typical dak-kamer atop, didn’t survive as late as 1961. The Provinsiale-gebou, home to the Western Cape Provincial Parliament, was built on the site in the 1930s. Those who viewed the 2009 AMC/ITV reinterpretation of “The Prisoner” might remember an outdoors nighttime city scene after the main character leaves a diner, with the street sign proclaiming “Madison Ave.” and plenty of yellow New York taxicabs streaming past. The large arches in the background are the front of the Provinsiale-gebou.

The House of Assembly

Die Volksraad

The House of Assembly (always called the Volksraad in Afrikaans, after the legislatures of the Boer republics) was South Africa’s lower chamber, and inherited the Cape House of Assembly’s debating chamber when the Cape Parliament’s home was handed over to the new Parliament of South Africa in 1910. The lower house quite soon decided to build a new addition to the building, and moved its plenary hall to the new wing. (more…)

Swinging round the Cape Peninsula

Visual editor and blogger Charles Apple gives us a photographic depiction of his Saturday touring the Atlantic side of the Cape Peninsula, from the V&A Waterfront, to Green Point, Three Anchor Bay, Sea Point, Clifton, Maiden’s Cove, Camps Bay, Bakoven, the Twelve Apostles, Llandudno, Hout Bay, and Chapman’s Peak. The photos are good, but still don’t do justice to that beautiful part of the world. They do, however, get me pining for the Peninsula!

The Senate of South Africa

Die Senaat van Suid-Afrika

THE SENATE OF South Africa has had something of a tempestuous history, a fact which is attested to by the vicissitudes of the Senate chamber in the House of Parliament in Cape Town. The Senate formed the upper house of South Africa’s parliament from the unification of the country in 1910, in accordance with the proposals agreed to by Briton & Boer at the National Convention of 1908. Its members were originally selected by an electoral college consisting of the Provincial Councils of the Cape, the Transvaal, the Orange Free State, and Natal, and the members of the House of Assembly (the parliament’s lower house), along with a certain number of appointments by the Governor-General on the advice of the Prime Minister. When South Africa abolished its monarchy, the State President took over the appointing role held until then by the Governor-General, but the Senate remained largely intact until 1981, when it was abolished in advance of the foolish introduction of the 1984 constitution with its racial tricameralism.

The Senate made a brief comeback in 1994, when the interim constitution provided for a Senate composed of ninety members, ten elected by each of the provincial legislatures of the new provinces. The 1994 Senate, however, was replaced by the “National Council of Provinces” in the final 1997 constitution. (more…)

The Houses of Parliament, Cape Town

Die Parlementsgebou, Kaapstad.

The insignia of the Parliament of South Africa, showing the Mace and Black Rod crossed between the shield and crest of the traditional arms of South Africa.

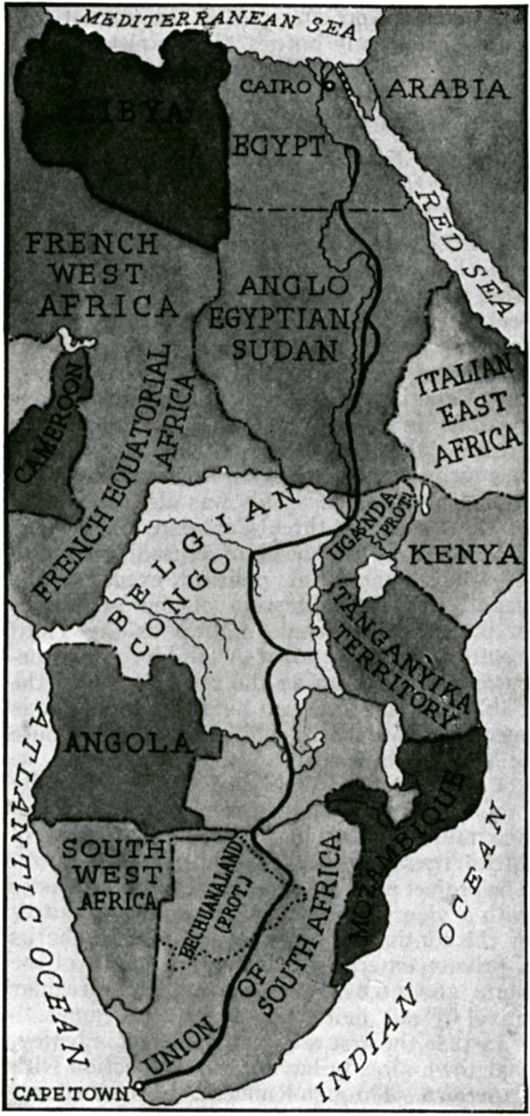

CAPE TOWN IS justifiably known as the “mother-city” of all South Africa, paying tribute to that day over three-hundred-and-fifty years ago when Jan van Riebeeck planted the tricolour of the Netherlands on the sands of the Cape of Good Hope. Numerous political transformations have taken place since that time, from the shifting tides of colonial overlords, to the united dominion of 1910, universal suffrage in 1994, and beyond. The history of self-government in South Africa has unfolded in a well-tempered, slow evolution rather than the sudden revolutions and tumults so frequent in other domains. No building has born greater witness to this long evolution than the Parliament House in Cape Town.

The British first created a legislative council for the Cape in 1835, but it was the agitation over a London proposal to transform the colony into a convict station (like Australia) that threw European Cape Town into an uproar. The proposal was defeated, but the colonists grew concerned that perhaps they were better guardians of their own affairs than the Colonial Office in far-off London. In 1853, Queen Victoria granted a parliament and constitution for the Cape of Good Hope, and the responsible government the Kaaplanders so desired was achieved. (more…)

The End of the Affair

HOW CAN ONE possibly summarize a portion of one’s life? Those first warm breaths of African air as I stepped off the plane at Cape Town International. The stern-faced mustachioed driver who drove me to Stellenbosch, the town that became my home, on my first day on the African continent. My strongest memory is just pure sunlight. I had flown down from the deepest winter of the northern hemisphere, and the sun’s warm embrace was a welcome change. As we entered the valley of Stellenbosch, my solemn driver broke the silence and asked what business was taking me there. Learning that I came, at least in part, to study Afrikaans, his dour visage was suddenly enlivened, and he earnestly gave every assurance that I would enjoy myself in Stellenbosch immensely.

The town itself is handsome, full of white-washed walls and pleasant streets lined with old oak trees, some planted by that Dutch governor of old, Simon van der Stel. He gave the town both its name — Stellenbosch, van der Stel’s wood — and its other moniker, Eikestad, the city of oaks. The most remarkable feature of the town, however, is the beautiful range of mountains that flank it on either side. My window happened to look out on Stellenbosch mountain itself, and I admit a certain territorial feeling towards that berg has formed through the several mornings, noons, and nights it has stood watch over me.

But pleasures though there are in Stellenbosch — a stroll the Botanical Gardens, a pint at De Akker, dinner at Cognito where they know my “usual” Tanqueray-and-tonic — even more awaits the Stellenboscher who ventures further afield. I went as far as Lüderitz in Namibia, one of the furthest extremities of the old German empire. But nearby Cape Town itself provides enough to keep the ardent traveller intrigued. Table Mountain, whose looming presence over the city frames the moederstad perfectly. Further along to the pleasant sands of Clifton’s beaches, the port of Simon’s Town, and down to the end of the Cape itself — the end of Africa, where two oceans meet.

And across False Bay to Rooiels and Betty’s Bay, to the Kogelberg reserve where the hiker’s efforts are rewarded by the seclusion of a splendid little swimming hole. Floating to and fro in the little river pond, being sung to by fair Finnish maidens — there are worse ways to spend a summer’s afternoon. But it’s also glorious to be alone in Kogelberg; to hear the silence of the dead summer, outstretched arms floating along, grazing the tall grass and the heather beside the way. The open, breezy country and the quieter nooks lodged between, whose heat betrays their stillness of air. Barely any sound but the crunch of foot upon path, the wind rustling through the plants, and the odd chirp of insect here and there.

And where else? To Wupperthal, where the barefoot coloured children play happily in the eucalyptus-lined street leading to the old Rhenish mission. To Kakamas, where the farmer invites us to lunch with his family, and guides us around just a few of his 600,000 acres. To Hermanus, spending two glorious hours clearing invasive plant species from a field before breakfast — that damned Ficus rubiginosa! To Greyton for a winter’s lunch beside the fireplace, and to Genadendal, the “valley of Grace”, the queen of the Moravian missions.

And with whom? Ah, the easy acquaintances of a university town. Friends from class, friends from the pub, friends from the bistro, friends of friends, and friends of friends of friends, who all end up as friends. To the beach on Friday? The cinema tonight? The pub quiz on Tuesday? A coffee tomorrow afternoon?

The people, more than anything, make the deepest impression — both the South Africans and my fellow travellers. Good times shared and conversations enjoyed. Some surprising friendships spring forth from the unlikeliest of places and the most scant of connections. And stories are shared of varying experiences. Poor Ralf almost getting done in by that hippo in the Kalahari! The intervarsity match — another victory for die Maties. And the second test match against the Lions — Morne Steyn, that kick! A genial cup of tea in a well-kept house in Oranjezicht as the resident explains how many times she’s been burgled. The Kayamandi girl whose father disappeared long ago, whose stepfather abuses her every night, and whose mother is entrapped into acquiescence by poverty. A student dies from swine flu — a first in South Africa. Another is murdered by the obsessed friend of her older brother. The police beat the suspect so badly he cannot appear in court. The headline in the Eikestadnuus proclaims “Vyfteen weeks, vyfteen moorde” — fifteen weeks, fifteen murders in this pleasant little corner of the Cape. The latest exhausted statement from Kapt. Aubrey Marais of the Stellenbosch police. An email from the university rector: male students are reminded not to allow girls to walk home unaccompanied at night. In the face of all this, ordinary lives continue unintimidated.

This country has a tendency to seep into the veins, to get under people’s skin. There is no brief affair with South Africa. Her own sons and daughters dot the globe — thousands are in London alone — but they earn their keep abroad while they yearn for the land they left. (“They just miss having servants” half-jokes the farmer’s wife.) Some do leave forever, but many more come home after a few years. My time is up, I leave South Africa today, but I can’t help but think the affair is not over, even if it only continues from afar. It is difficult to escape the lure of this deeply troubled, deeply blessed land.

The Rhodes Memorial

PERCHED AMID THE bluegum trees on the slopes of Devil’s Peak in Cape Town is the memorial to one of the most brilliant & cunning men the world has ever produced. Cecil John Rhodes may have been born in Bishop’s Stortford, England, but his worldly glories all emanated from the Cape of Good Hope, and so it’s appropriate that his memorial stands here in Cape Town. His first commercial enterprise in South Africa was founding the Rhodes Fruit Farms (now Rhodes Food Group) which still exist on the road from Stellenbosch to Franschhoek, and has since expanded throughout the Western Cape, and to the Transvaal and Swaziland. But it was his creation of the diamond monopoly De Beers out of the Kimberley mines that made him one of the wealthiest men in the world. Ten years after being elected to the Cape Parliament, he was made Prime Minister of the Cape in 1890, but his catastrophic and illegal attempt to seize the independent Transvaal in 1895 forced his resignation from politics in disgrace. (more…)

Leeuwenhof

One of the better aspects of the job of Premier of the Western Cape is Leeuwenhof, the official residence that comes with the job. The estate on the slopes of Table Mountain dates from the days of the Dutch East India Company. That renowned governor of old, Simon van der Stel (after whom both Simonstad & Stellenbosch are named), granted the land to Guillaum Heems, a free burgher, to ‘clear, plant, plough, develop and work’. Heems christened the land Leeuwenhof — “Lions Court” — but sold it just two years later to Heinrich Bernhard Oldenland, Master Gardener of the Company’s Garden and Superintendent of Works for the Dutch East India Company.

Oldenland died just a few months after purchasing Leeuwenhof, and it passed into the hands of the fiscal Blesius, whose widow’s death put the estate under a series of masters until it was sold it for 14,000 guilders to Johan Christiaan Brasler, a Dane. Brasler enjoyed a good many years there in prosperity of late-eighteenth-century Cape Town, a period when the building of stately homes, townhouses, and government buildings became (as Cornelis de Jong put it at the time) “a passion, a craziness, a contagious madness that has infected nearly everyone”. This was the age of Thibault, Anreith, and Schutte — the true golden age of Cape Town’s stately finery. Inspired by the “madness” of which De Jong tells, the Dane Brasler converted the humble farmhouse of Leeuwenhof into the dignified abode we know today. (more…)

A Good Day in Cape Town

The South African Royal Family’s 1947 visit to “Die Moederstad”

SOUTH AFRICA IS a nation that took a long time birthing, from the first steps van Riebeeck took on the sands of Table Bay in 1652, through the tumult of the native wars, the tremendous conflict between Briton & Boer, and ultimately what was hoped would be the final reconciliation in Union of South Africa — 1910. In that year, young Prince Albert of York & of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was just fifteen years of age, and South Africa became a dominion just weeks after his father became King George V.

Albert was the second son of a second son, so at the time of his birth (and for most of his early life) it was never expected that he would one day be King of Great Britain, Emperor of India. It was his brother’s abdication that thrust poor Bertie, as he was always known to his loved ones, upon the throne imperial. It was a cold December day in 1936 that the heralds of the Court of St. James proclaimed him George VI.

By his nature, the King was a quiet and reserved man, partly because of the stammer that impeded his speech. George VI was happiest among his family, and they accompanied him in 1947 on a long voyage aboard HMS Vanguard, to his far-off kingdom on the other side of the world, where the two oceans meet. It was the first time a reigning monarch has set foot on South African soil, and Capetonians waited in earnest anticipation to see their sovereign. How appropriate that this happy city — moederstad, or “mother-city”, of all South Africa — would be the first to receive him. (more…)

It’s good to be Prime Minister

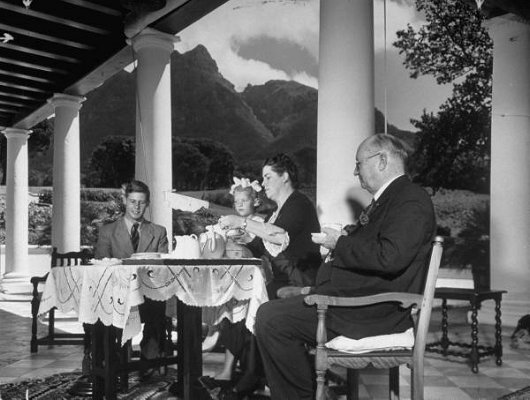

Daniel François Malan, fourth Prime Minister of South Africa, is seen here taking breakfast with his family on the verandah at Groote Schuur, the official residence of the PM. (At right, the same view today). Groote Schuur — literally “great barn” — was purchased by Cecil Rhodes and transformed into the paragon of the South African style of architecture by his architect Sir Herbert Baker. Foolishly, the office of Prime Minister was abolished in 1984, when the ridiculous 1984 tricameral constitution was adopted. Groote Schuur continued as the Cape residence of the State President of South Africa under P.W. Botha and F.W. De Klerk but when Nelson Mandela was elected he decided to make the neighbouring Westbrooke his official residence, renaming it Genadendal (“Valley of Grace”) after the oldest Moravian mission in South Africa. Groote Schuur is now a museum open by appointment, and unlived in.

Daniel François Malan, fourth Prime Minister of South Africa, is seen here taking breakfast with his family on the verandah at Groote Schuur, the official residence of the PM. (At right, the same view today). Groote Schuur — literally “great barn” — was purchased by Cecil Rhodes and transformed into the paragon of the South African style of architecture by his architect Sir Herbert Baker. Foolishly, the office of Prime Minister was abolished in 1984, when the ridiculous 1984 tricameral constitution was adopted. Groote Schuur continued as the Cape residence of the State President of South Africa under P.W. Botha and F.W. De Klerk but when Nelson Mandela was elected he decided to make the neighbouring Westbrooke his official residence, renaming it Genadendal (“Valley of Grace”) after the oldest Moravian mission in South Africa. Groote Schuur is now a museum open by appointment, and unlived in.

The Groote Kerk

Dr. van der Merwe, moderator of the Dutch Reformed Church, poses in the splendidly carved pulpit of the Groote Kerk in Cape Town.

The Mayoress of Cape Town

Die Burgemeester van Kaapstad

AND SO, Helen Zille, the Mayor of Cape Town, has been elected Leader of the Opposition in South Africa, a somewhat curious choice to head the country’s (liberal) Democratic Alliance against the current government (the ANC alliance of racial nationalists, the Communist Party, and the trade union confederation) as she is not actually a member of parliament and has stated that she has no intention of seeking election to that body. If only she would bring a little more reserve to the council chamber, a virtue she is sadly lacking (as evidenced in pictures above and below).

Ms. Zille has a reputation as a bit of a go-get-em mayor, and something of a pragmatist, which is welcome, as any efforts that chip away at the rule of the noxious African National Congress are wholeheartedly welcome. And she’d have to try hard to be any worse in her new job than her noxious predecessor, ‘Tony’ Leon. While we would probably vote (depending on geography) for the Inkhata Freedom Party or the Vryheidsfront, we wish Ms. Zille luck as Leader of the Opposition.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories