World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

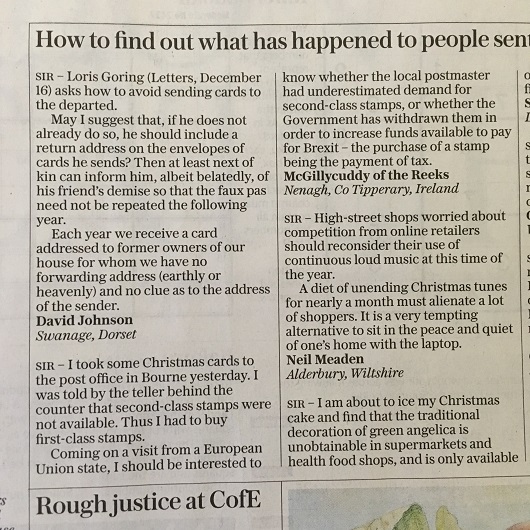

The McGillycuddy of the Reeks

How lovely to see a member of the Gaelic nobility – in this case, the McGillycuddy of the Reeks – having a letter printed in the newspaper (Daily Telegraph, Letters, Wednesday 20 December 2017).

His title is somehow the most fun of all the Chiefs of the Names, though not all bearers of the chiefdom have found it amusing. In the early years of the BBC, the ‘Green Book’ instructing comedy producers what they could and could not get away with contained the instruction ‘Do not mention the McGillycuddy of the Reeks or make jokes about his name’. Clearly a protestation had been made.

Looking at the map of Kerry on my kitchen wall, the eye often drifts to McGillycuddy’s Reeks themselves, the “black stacks” amongst which can be found Corrán Tuathail, Ireland’s tallest mountain.

“Get me ze Führer!”

Stereotypes of Nazi generals in British war films

“The reason for my uniform being a slightly different colour to yours

is never explained.”

The British are, of course, obsessed with the Nazis. There are many reasons for this, amongst which we must include the large number of really quite good war films produced during the 1950s and 1960s.

For some indiscernible reason these movies have the virtue of being eternally rewatchable and many a cloudy Saturday afternoon has been occupied by Sink the Bismarck!, Where Eagles Dare, or The Colditz Story.

The genre also deploys with a remarkable regularity a number of familiar tropes of ze Germans which the above clip from a British comedy sketch programme (introduced to me by the indomitable Jack Smith) aptly mocks.

F.C. Kolbe and the Tulbagh Drostdy

the Tulbagh Drostdy

Poet, Polemicist, Polymath, and Priest

Relic and emblem of a storied past.

Thrice happy they whose lines in thee are cast

Thy records summon all in thy embrace

To emulate the virtues of the race.

Thy stately halls of courtly manners tell,

Where only Ladies Bountiful should dwell.

Thy solid frame is pledge of future glory,

And links our doings with our country’s story.

Work on the Drostdy (magistrate’s house) at Tulbagh in the Western Cape began late in 1804 but progressed rather slowly and expensively. This is probably because — after construction commenced — the plans by Bletterman, the landdrost at Stellenbosch, were torn up by the architect Louis Michel Thibault and replaced by his own design.

This meant part of the work already completed had to be demolished and re-done, which Bletterman only went along with assuming Thibault’s plan had the approval of the Batavian Republic’s governor of the Cape, Jan Willem Janssens. As it happens, they did not, and when Bletterman found out he was none too pleased.

Francis Masey, a partner at Herbert Baker’s firm, noted that “[w]hilst it proved to be the last building begun upon Dutch soil in South Africa, it was destined to be the first completed upon the passing of the Cape into the hands of the British.”

This  brief ode was written by Frederick Charles Kolbe (right) in 1909. The great-great-grandson of the magistrate (or landdrost) at Stellenbosch, F.C. Kolbe was the son of a Congregational missionary in Paarl who studied law at the Inner Temple in London. There, in 1876, he was received into the Catholic Church and continued on to study in Rome where he was ordained a priest in 1882.

brief ode was written by Frederick Charles Kolbe (right) in 1909. The great-great-grandson of the magistrate (or landdrost) at Stellenbosch, F.C. Kolbe was the son of a Congregational missionary in Paarl who studied law at the Inner Temple in London. There, in 1876, he was received into the Catholic Church and continued on to study in Rome where he was ordained a priest in 1882.

While his poetry was tended towards the middling, Kolbe was a distinctive polymath. In addition to catechetical writings, he published a number of works on Shakespeare, and lectured on Socrates not long after his 1882 return to the Cape. Eventually he was appointed Reader in Aesthetics at the University of Cape Town.

Kolbe also wrote a Catholic criticism of the 1926 book Holism and Evolution by the statesman General Smuts. (Not many people realise that the word ‘holistic’ was donated to the English language by a son of Stellenbosch.) The general and the priest had corresponded as early as 1915 when Smuts was Minister for Defence, and Smuts was so taken with Kolbe’s critique that he wrote a foreword to a later edition of it.

In a 1935 letter to “Dr. Kolbe”, the General wrote:

Although I am not acquainted with the Catholic prayers, I am deeply versed in the Psalms of the Old Testament, which seem to me the greatest and noblest outpourings of the human spirit ever put into language. The inexpressible finds expression there. Emotions almost too deep for utterance somehow find an outlet there. …

I also agree with you as to the nobility of the language which Catholic Christianity has evolved. What could match the beauty of De Imitatione Christi? Somehow it breathes a spirit which is beyond all language. It is curious how in such a case the human soul sets on fire its own earthly vesture, and language becomes a blaze of glory…

From Smuts’ letters to others we know that he actually read more works by Kolbe, in particular his Up the slopes of Mount Sion: or, A progress from Puritanism to Catholicism.

Disputation and discussion were also among Kolbe’s talents. He used the pages of South Africa’s Catholic Magazine to counter the accusations of what he called a “narrow clique” of anti-Romish ministers of the Dutch Reformed Church.

One of Kolbe’s most lasting legacies was the effect of his writing on the young Afrikaner philosopher Marthinus Versfeld (1909–1995) who converted to Catholicism under the late Monsignor’s influence. (Kolbe had died in 1936.) Versfeld’s familiarity with Augustine and Aquinas helped him launch intellectual attacks against the so-called “Christian-national” thinking behind apartheid, particularly in his first book Oor gode en afgode (“Of Gods and Idols”, 1948 & republished 2010).

Kolbe, according to Versfeld, “lived out a certain apprehension of the presence of the universal in the particular, just as Newman lived out his vision of the Catholic Church in the material of English circumstances.”

An Afrikaner Newman, perhaps? Worth reading more about.

The French Way of War

I’ve  been reading Lartéguy recently so was intrigued to hear of another French writer formed by his military experience, Pierre Schoendoerffer (right).

been reading Lartéguy recently so was intrigued to hear of another French writer formed by his military experience, Pierre Schoendoerffer (right).

In a tweet, the cigarette-smoking Helen Andrews shared an article called What a 1963 Novel Tells Us About the French Army, Mission Command, and the Romance of the Indochina War.

I dislike the romanticism surrounding the magnificent losers vs. ugly victors dichotomy – a magnificent victory is infinitely preferably to both. Hence why my natural Jacobite sympathies are highly qualified by complete and utter disdain for Charlie’s unwillingness to see the task through. (An easy judgement when made from centuries of hindsight, I’ll concede.)

Anyhow, I sent the article to The Major and he proffered this reply:

I was going to say something snide about the French army but to be quite honest I have thought for some time that it is rather better than ours [Ed.: the British]. Their officers are tougher, harder, and more professional than ours – those I encountered professionally certainly were. They are also not infected by the political correctness which is wrecking/has wrecked our army (among other factors).

The distinction between the colonial army and the large conscript army at home is valid. It was the conscript army which was defeated in 1870, 1914, and 1940… not the colonial army to which the modern French army now looks.

It is also true that the US Army don’t do Mission Command well. The Marines on the other hand…

Meanwhile back in the States the prolific Ken Burns has done an eighteen-hour documentary on the Vietnam conflict which allegedly ignores all the scholarly input of the past two decades. Nevermind, we just regret it won’t feature the late great Shelby Foote, who (in Burns’s ‘The Civil War’) spoke with such assurance you imagined he was there.

Justice in the Royal Gallery

One of the great triumphs of Magna Carta was the assertion of the right of those accused of crimes to trial by one’s peers, or per legale judicium parium suorum if you insist on the Latin. For commoners this meant trial by other commoners, but for peers it meant just that: trial by other peers of the realm. It was a bit murkier for peeresses, though after the conviction for witchcraft of Eleanor, Duchess of Gloucester, (sentence: banishment to the Isle of Man) statute was passed including them in the judicial privilege of peerage.

Thanks to the ’15 and the ’45, there were a number of trials in the House of Lords in the eighteenth century, including that of the Catholic martyr Earl of Derwentwater. The whole of the nineteenth century, however, witnessed but one: the 7th Earl of Cardigan was acquitted of duelling by a jury of 120 peers. In 1901 the 2nd Earl Russell was found guilty of bigamy, and the last ever trial came in 1935 when the 26th Baron de Clifford was found not guilty of manslaughter.

Cardigan’s trial was in the temporary Lords chamber while the last two trials took place in the Royal Gallery of the Palace of Westminster (central to current debates over renovation plans). For Cardigan’s trial the Lord Chief Justice of the Queen’s Bench was appointed Lord High Steward for the occasion, while for the final two the Lord Chancellor was likewise appointed to the role in order to be presiding judge with the Attorney General prosecuting the case.

The Royal Gallery is primarily used for the State Opening of Parliament (as above) and for the occasional address to both Houses of Parliament when important figures are invited to do so. De Gaulle was famously invited to speak here to both houses rather than in the larger Westminster Hall. It is thought that this is because the walls of the Royal Gallery feature two large murals, one of the Battle of Trafalgar, the other of the Battle of Waterloo – both British victories over the French.

The most famous trial in the Royal Gallery was fictional. In the 1949 Ealing comedy “Kind Hearts and Coronets”, the 10th Duke of Chalfont is tried for the one murder in the film’s plotline he didn’t actually commit. Ealing Studios did a mock-up of the chamber for the occasion (above), which compares reasonably accurately with the Royal Gallery as set up for the Baron de Clifford’s trial in 1936 (below).

The Lords, however, were uncomfortable with exercising this judicial function and passed a bill to abolish the privilege in 1937. The Commons, facing more serious tasks, declined to give it any attention. In 1948, the Criminal Justice Act abolished trials of peers in the House of Lords, along with penal servitude, hard labour, and whipping.

Hougaard Malan

South African Landscape Photographer

When I lived in South Africa I began to understand the deficiencies of photography. The scenery in which one we had the privilege of acting out “the foolish deeds of the theatre of our day” (as Mr Mbeki put it in one of his better speeches) was stunning, but on the few occasions I bothered to put my Leica to good use the results were disappointing. You’d look at a photograph that was admittedly beautiful but still think to yourself “But in real life it was a thousand times more beautiful than that!” Needless to say, my own lack of skill as a photographer is the most obvious cause.

Hougaard Malan, meanwhile, is one of the few photographers who manages to almost, nearly capture the beauty of the South African landscape. In each and every shot — and some of these places are well known to me — the scale and drama of the location shines forth.

“Growing up, my grandmother always gave me illustrated encyclopedias and books about earth’s natural history that were filled with fantastic landscape images,” Mnr Malan says. “I spent many afternoons paging through these books and marvelling at nature’s beauty. Few things in life made me feel more alive than a landscape that engaged all my senses – seeing the rhythmic rolling of waves in a bay, smelling the coastal flora, hearing and feeling the ocean crash against the cliffs and then tasting the salt in the air.”

Mnr Malan’s website can be found here but here is just a small sampling of the photographs of southern Africa and well beyond which this talented man has taken.

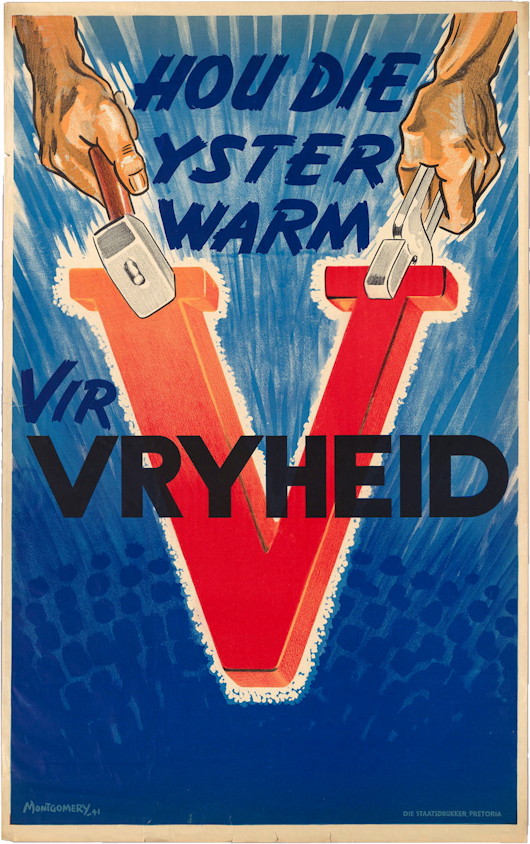

V for Victory (en Vryheid)

The twenty-second letter of the alphabet became a powerful symbol during the Second World War — ‘V’ for Victory, and all that. Even the Morse code for the letter — dot-dot-dot-dash — became useful, echoing as it did the famous four-note motif from Beethoven’s fifth symphony.

In South Africa, however, the two main languages were English and Afrikaans, and the Afrikaans word for victory, oorwinning, does not start with a ‘V’. Instead the letter was used to stand for vryheid, or freedom, just as in Belgium it stood for both victoire for the Walloons and vrijheid for the Flemings.

When the Second World War started Prime Minister Hertzog announced a policy of neutrality, only to be toppled as premier by his deputy and ally Smuts who brought South Africa into the war a few days later than Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

This wartime propaganda poster, produced by the Staatsdrukker in Pretoria, urges South Africans to ‘keep the iron hot for freedom’. The country’s industrial production made a valuable contribution to the war effort in addition to the volunteer manpower of the Union Defence Force and, perhaps most importantly, the gold that came from the Witwatersrand mines.

From Realm to Republic

South Africa’s transition from a monarchy to a republic coincided with a change of currency. Out went the old South African pound (with its shillings and pence) and in came the decimilised rand.

Luckily the republican government had the good taste to commission George Kruger Gray, responsible for the country’s most beautiful coinage, to design the new coins. HM the Queen was replaced by old Jan van Riebeeck, and the country’s arms were deprived of their crown.

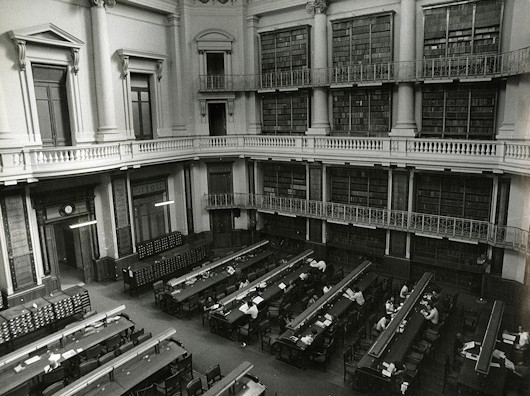

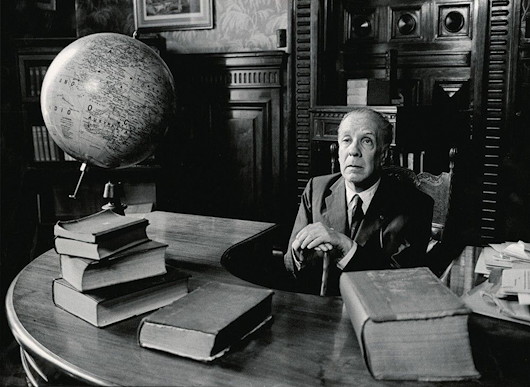

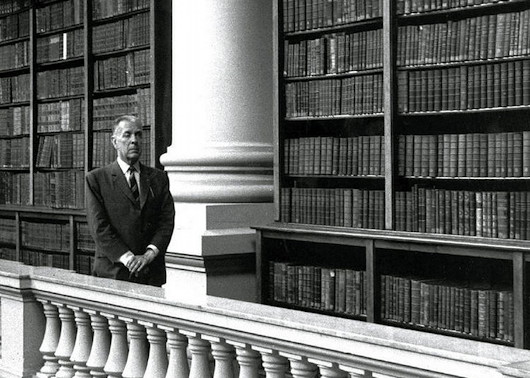

Borges’s Biblioteca

The old National Library on Calle Mexico in Buenos Aires

The intellectual Alberto Manguel grew up amidst the library of the Argentine diplomatic compound in Tel Aviv, as he recalls in this piece for Britain’s strangely underappreciated Literary Review.

At the end of 2015 Señor Manguel was appointed director of Argentina’s National Library, taking up his position in the middle of last year. In this role he steps into the shoes of Jorge Luis Borges who led the institution from 1955 until he resigned upon Peron’s return in 1973.

Returning to the ‘Queen of the Plata’ after a long career in exile was not a simple affair. As Señor Manguel writes:

The city, of course, was different. I found it difficult to look at the actual streets and houses without remembering the ghosts of what had been there before, or what I imagined had been there before. Buenos Aires felt now like one of those places seen in dreams, the geography of which you think you know but which keeps changing or drifting away as you try to make your way through it.

The National Library I had known during my adolescence was a different one. It stood on Mexico Street in the colonial neighbourhood of Montserrat. The building was an elegant 19th-century palazzo originally built to house the state lottery but almost immediately converted into a library. Borges had kept his office there when he was appointed director in 1955, when ‘God’s irony’, he said, had granted him in a single stroke ‘the books and the night’. Borges was the fourth blind director of the library, a curse I’m intent on avoiding. It was to this building, during the 1960s, that I used to go to meet Borges after school and walk him back to his flat, where I would read stories by Kipling, Henry James and Robert Louis Stevenson to him. After he became blind, Borges decided not to write anything except verse, which he could compose in his head and then dictate. But some ten years later he went back on his resolution and decided to try his hand again at a few new stories. Before starting, Borges wanted to study how the great masters had gone about writing their own. The result was two of his best collections, Doctor Brodie’s Report and The Book of Sand.

The library I discovered half a century later was lodged in a gigantic tower designed in the brutalist style of the 1960s. Borges, passing his hands over the architect’s model, dismissed it as ‘a hideous sewing machine’. The building is supposed to represent a book lying on a tall cement table, but people call it the UFO, an alien thing landed among pretty gardens and blue jacaranda trees. […]

In my adolescence, I tried to write, no doubt under the influence of Borges, a few fantastical stories, now fortunately lost. One of them was about an unbearable know-it-all to whom the devil, in exchange for I don’t recall what, entrusted the overseeing of the world. Suddenly, this oaf realises that he has to deal with everything at once, from the rising of the sun to the turning of every page of every book, and the falling of every leaf, and the coursing of every drop of blood in every vein, and he is crushed by the inconceivable immensity of the task.

I had wanted to try to put my ideas about reading and libraries into action ever since I received my first books. Now I have got my wish with a vengeance. I have never in my life done anything as demanding and overwhelming as directing the National Library of Argentina. I have become, from one day to the next, an accountant, technician, lawyer, architect, electrician, psychologist, diplomat, sociologist, specialist on union politics, technocrat, cultural programmer and, of course, librarian. I hope that, time and Argentinian politics permitting, I’ll be able to start a few things that may allow us to have, in the not too distant future, a national library we can be proud of.

First Gypsy Woman Martyr is Beatified

Emilia Fernández Rodríguez was killed during Spanish Civil War

The Catholic Church has beatified its first gypsy martyr in a ceremony in the Spanish city of Almería on the southern Mediterranean coast. Emilia Fernández Rodríguez, also known as “La canastera” (the basket-weaver), was one of 115 martyrs murdered in odium fidei by anti-Catholic militants during the Spanish Civil War.

The beatification ceremony took place in the city’s conference centre attended by over 5,000 people, including twenty-one bishops and four cardinals.

In 1938, Blessed Emilia Fernández was a poor gypsy woman living with her husband in Tíjola and surviving by basket weaving when the Republican forces occupied the town, shutting its church, and conscripting its menfolk. Emilia’s husband Juan with her help feigned blindness to escape conscription but was discovered and the couple were imprisoned separately.

Arriving at the women’s prison in Gachas-Colorás, Blessed Emilia was already pregnant and was jailed alongside many other practicing Catholic women who had refused to abjure their faith. Illiterate and never having been catechised despite being baptised, Blessed Emilia was taught how to pray the Rosary by another inmate. Her devotion to this Marian prayer and meditation attracted the ire of the prison authorities who threw her into solitary confinement for refusing to reveal which of her fellow inmates had catechised her.

After the birth of her baby girl, Ángeles, Blessed Emilia died as a result of her weakened condition from malnutrition and the appalling conditions of her isolation. Just twenty-three years old, her body was dumped into a common grave in Almería.

South Africa in the Old Days

This historical film about the early days of the Cape was probably produced for the van Riebeeck tercentenary festival of 1952.

The clip here covers the days of Governor Willem Adriaan van der Stel, depicting them as carefree days of harmony and merriment in South Africa – in contrast to Europe where war and persecution reigned. Doubtless this was how the apartheid government sought to portray South Africa at the time: a haven of peace and prosperity in contrast to a Europe still recovering from war, with half the continent now under the Soviet boot.

Simplistic propaganda of course, but the film conveys a certain charm regardless, as does almost every depiction of the Cape before the British. The sight of geese flocking before an old Cape Dutch homestead (circa 7:00) never fails to touch the Cusackian heart…

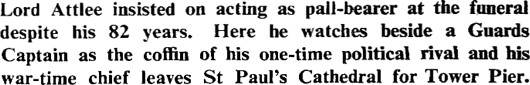

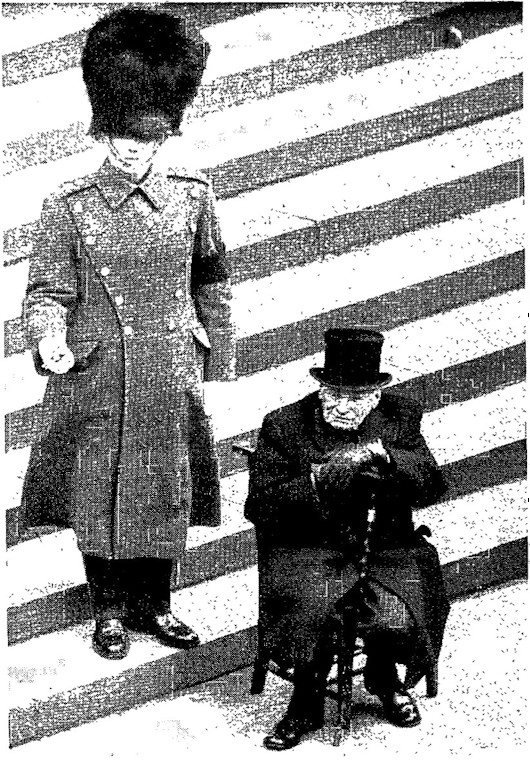

The Earl Attlee

At Chartwell one weekend in Churchill’s presence, Sir John Rodgers made the mistake of referring to Clement Attlee, wartime deputy prime minister and postwar prime minister, as “silly old Attlee”. Churchill was having none of it.

“Mr Attlee is a great patriot,” he said. “Don’t you dare call him ‘silly old Attlee’ at Chartwell or you won’t be invited again.”

The leader of the Conservative party and the leader of the Labour party were obvious political rivals but developed a great bond by their shared experience in the cross-party War Cabinet.

En route to a dinner party the other night I happened to run into Attlee’s greatgrandson (an old friend) on the upper deck of the 414 bus. It reminded me of this photo (above) printed in the Observer. When the great bulldog went on to his eternal reward in 1965, the incredibly frail Earl Attlee insisted on attending the state funeral in St Paul’s Cathedral. Though younger, he only managed to outlive him by two years.

Attlee had been raised to the House of Lords (where he spoke against Britain joining the EEC) in 1956 and, rather appropriately, he chose as the motto for his coat of arms Labor vincit omnia — Labour conquers all.

Challoner’s House

Challoner’s House — Rather humble for an episcopal palace, but such was the function of No. 44, Old Gloucester Street in Holborn during the time of Bishop Richard Challoner.

If it seems an odd spot for London’s Catholic bishop, it can be explained by its close proximity to the chapel of the Sardinian Embassy off Lincoln’s Inn Fields. At this time, of course, the Mass was still illegal and the only places Catholics in London could worship were the embassies of the Catholic nations. To protect the underground bishop, the house in Old Gloucester Street was actually rented in the name of his housekeeper, Mrs Mary Hanne.

After a perfect breakfast on Saturday morning the sun was shining so I decided the three-and-a-half miles home from St Pancras were best managed on foot. If architectural or historical curiosities are your fancy then foot is the way to travel, and so it was by pure chance that I stumbled upon No. 44. It seemed particularly appropriate that the night before a whole gang of us — Brits, Swedes, Italians, etc. — had been drinking in the Ship Tavern in Holborn where Bishop Challoner was known to offer the occasional clandestine Mass. (more…)

The Old Scots College

Via delle Quattro Fontane, Rome

Next month I’m off to Rome and the last time I was there I happened to walk past the old Scots College on the via delle Quattro Fontane. The Pontifical Scots College is probably the oldest Scottish institution abroad and certainly one of the most important, both historically and today. As Scotland’s primary seminary it has — almost literally — helped form the soul of the country, particularly during times of widespread persecution back in the mother country.

The church of Sant’Andrea degli Scozzesi (St Andrew of the Scots) was built in 1592 during the reign of Clement VIII, and early in the seventeenth century the church and neighbouring hospice were given over to the Scots College which had been founded a few years before. The seminary building itself was (I believe) built much later, in the nineteenth century after the college briefly ceased instruction due to the tumult of the French Revolution.

Sadly the building was not very well maintained and by 1960 it was falling apart. It was decided to sell the old college buildings in the Via delle Quattro Fontane and move to a larger site out the middle of nowhere in the Via Cassia. The move was made in 1964, and the Scots College has remained there ever since, while the old college housed a bank for many years and more recently a lawfirm.

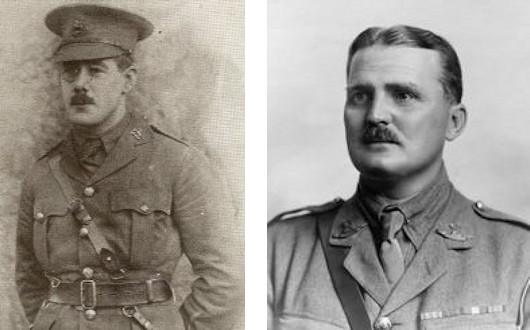

South African VCs in the Russian Civil War

The South African contribution to the Russian Civil War is not very well known, nor particularly well researched by historians of the period. Several South African officers who found themselves in Europe by the time of the armistice ending the Great War volunteered to serve in Russia fighting the Bolsheviks — either with the Allied force there or with the White forces themselves.

Among the South African volunteers were two winners of the Victoria Cross — Major Oswald Reid (above, left) of Johannesburg, and Lt Col John Sherwood-Kelly (above, right) from the Eastern Cape.

The South African aviation pioneer K R van der Spuy — who ended up a major general — managed to serve from the early days of 1914 all through the First World War. His engine failed in Russia, however, and he was taken prisoner after a forced landing in Bolshevik-held territory. The Soviets released him from imprisonment in 1920.

As Cdr W M Bisset wrote elsewhere: “Despite the harshness of the Russian winter and the growing prowess of the Red Army, South African officers were able to make a valuable contribution to the operations of the Allied and White Armies which is well illustrated by the important posts which they held and the awards they received.”

Fillon: Which Right?

A Rémondian Analysis of the French Presidential Candidate

One of the most significant contributions of the historian and political scientist René Rémond was his theory regarding the tendencies of the French right wing. He contended that, broadly speaking, there are three right wings in France: legitimist, bonapartist, and orleanist. These terms are not bound by their historic use, but rather (Rémond argued) serve as useful guides to understanding French conservatism today.

Gaullism, for example, with both its populism and its reliance on the authority of a charismatic leader, is classified as bonapartist. Social conservatism, meanwhile, with its affinity for the Church and for tradition, comes in under legitimism. And economic liberalism — the bourgeois supremacy of the markets — is orleanist.

What to make of the current presidential candidate of the French right, M François Fillon? The Québécois website Dessinons les élections (“Let’s draw the elections”) sought to apply a Rémondian analysis of Monsieur Fillon in one of its weekly cartoons (by Frédéric Mérand & Anne-Laure Mahé).

Their conclusions are as follows:

Legitimism: 60%

– social conservatism

– Christian values

– order and traditionOrleanism: 30%

– economic liberalismBonapartism: 20%

– a sense of the State

– idea of the providential man with reference to de Gaulle

Of course, many now think that, due to the usual scandals, Fillon is yesterday’s man and that Macron is the man of the hour. The two are chalk and cheese. Fillon is the family man from the country, loves hunting, and clings to the values of the Church. Macron is a socialist énarque and investment banker who married one of his school teachers (twenty-four years his senior).

The elephant in the room: Madame Le Pen. The leader of the Front national will, there is almost no doubt, top the first round of the election but then, in the second round, will have to face whichever other candidate gains the next highest number of votes. Whoever that candidate is will almost certainly gain all the anti-frontiste votes and be propelled to victory and the Elysée.

At the moment, it looks like the second candidate will only have to win around 22 per cent of the vote in order to effectively gain the presidency. Such a low level of actual support is one of the things the 1962 changes to the constitution sought to prevent, but when faced with an FN candidate as in 2002 or (presumably) this year the two-round system fails to prevent this.

As usual, the conservatives are calling for change and the progressives arguing for stasis, but it remains to be seen which option France will choose.

The slums of the Louvre

We are so used to the now-familiar image of the palais du Louvre — with its central wing and flanking arms wide open to the Jardin des Tuileries — that it’s easy to forget just how recent a creation this ensemble is. The palace began as a square chateau expanding upon the site of the medieval citadel. The Tuileries it eventually stretched towards was then an entirely separate palace. In-between the Louvre and the Tuileries was a whole neighbourhood of buildings, streets, alleyways, and squares.

Henri IV built the grande galerie on the banks of the Seine connecting the Old Louvre to the Tuileries by 1610, but the Louvre we know today really only came together under Napoleon III in the 1850s.

Until that point, a slum was built right up to the walls of the Palace, and even within the old courtyard. Balzac, predicting that one day all this would be cleared, noted the slum with amusement as “one of those protests against common sense that Frenchmen love to make”. (more…)

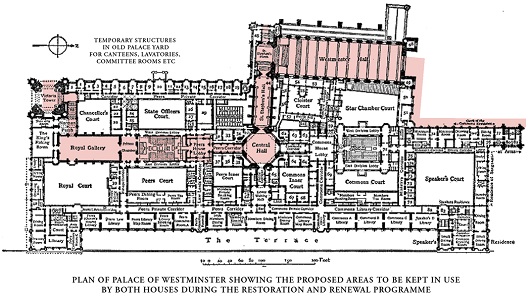

The Delarue Proposal for Parliament

Peers & MPs could still convene in the Palace during renovations

The Royal Gallery set up for temporary use as the House of Lords chamber

Credit: Anthony Delarue Associates

MPs are kicking up a fuss about the controversial proposals to shut down the entire Palace of Westminster for perhaps as long as eight or nine years. (Previously mentioned here.) The building is completely structurally sound, and on solid foundations, but the accumulation of mechanical, electrical, and technological systems over the course of the past 150 years has created a confused mess within the walls of the palace. Electrical lines compete with fibre-optic cables, telephone wires, not to mention various heating and cooling pipes, and even some lingering telegraph wires. No one’s quite sure what is what and all of it is getting older. Even just accessing it to figure out what to do requires taking the building apart — removing wood panelling, drilling through walls, etc.

Parliamentary authorities commissioned management consultants from Deloitte to come up with a number of options on how to tackle this problem, but in their Independent Options Appraisal they treated this merely as an ordinary engineering job, rather than recognising the Palace as one of the most important places in British history both medieval and modern and, importantly, one still in constant daily use.

The Joint Committee formed of members of both the Lords and Commons perhaps unsurprisingly endorsed the option Deloitte claimed was the quickest and cheapest: that the Lords, Commons, and everyone else be chucked out of the Palace entirely and that temporary accommodation be found nearby.

Further investigation by respected former minister Shailesh Vara MP suggested that Deloitte had failed to take into account that any VAT costs on this major project go back into the Treasury anyhow, and that there was a failure to account for the loss of revenue if the Lords are moved into the government-owned Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre nearby. The QE2 is a profit-making venue popular with private clients, after all, and deploying it towards full-time legislative use will mean another significant loss for the Treasury. Meanwhile, in the courtyard of Richmond House on Whitehall, £59 million would be spent on building a new chamber for the House of Commons. This would be a permanent ‘legacy’ structure even though once the renovations to the Palace are complete there would be no use for it whatsoever.

The architect Anthony Delarue, having been taken on a tour of the Palace’s working underbelly by the engineers from the Restoration and Renewal programme, came up with an alternative proposal. Looking at the structure of the House of Lords chamber and the adjacent Royal Gallery, he realised that these two rooms could be maintained and occupied, with temporary services (electricity, heating, etc.) run from external sources. This would allow the renovation team to shut down the Palace’s systems entirely and re-do them completely, while the spaces in mind would still be able to be put to use. The Commons could then meet in the Lords chamber (as the wartime precedent suggested) and the Lords could meet in the Royal Gallery. Or indeed vice versa depending on the wishes of both Houses.

The advantages of this are no need for taking up the QE2 conference centre (with consequent loss of revenue for the Treasury) and no need to waste tens of millions on a temporary-but-permanent Commons chamber in the courtyard of Richmond House. In addition, both houses would be allowed to maintain their presence in the Palace of Westminster, in accommodation suitable to the traditions of the “Mother of Parliaments”.

Of course, the Restoration and Renewal programme ran a “high level review” of Delarue’s proposals and pooh-poohed the whole idea, amazingly claiming that it would probably cost £900 million more than the Deloitte option the Joint Committee preferred. Anthony Delarue has now written some comments responding to this review, pointing out that it relies on outrageously pessimistic estimates of timing, assumptions that are beyond the worst-case scenarios of project management.

MPs were expected to debate the matter last month, but the campaign organised by Sir Edward Leigh MP and Shailesh Vara MP has found considerable support among other Members of Parliament and it is believed the powers that be are looking for a delay. The Government have promised a free vote on the issue when it comes up for debate, which may very well be before the end of February.

● Anthony Delarue Proposal

● Deloitte Independent Options Appraisal

● Joint Committee Report

● High Level Review of Delarue Proposal

● Anthony Delarue Response to High Level Review

Credit: Anthony Delarue Associates

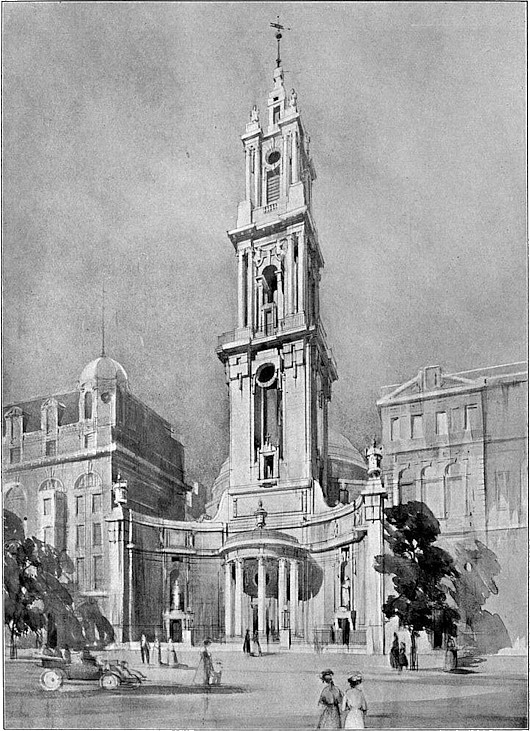

Holy Trinity Kingsway

Holy Trinity, Kingsway

Not much information is available about this church. The architect was John Belcher but the ambitious tower was never built, nor was there much money to complete the interior.

After it was made redundant in the 1990s the church was demolished — except for the façade so obviously influenced by Santa Maria della Pace.

The Queen

1992; Oil on canvas, 96 in. x 60 in.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories