World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Stellenbosch

would be as beautiful as Oxford or Cambridge

until I saw it.”

— AIDAN HARTLEY

Soho Iridescent

Stiff & Trevillion’s 40 Beak Street in London

Beak Street in London is teeming with turquoise iridescence since the completion of a new office building by the architectural firm of Stiff & Trevillion earlier this year. A joint project between property investment companies Landcap and Enstar, Number 40 Beak Street has been purchased for £40 million by Damien Hirst — the canny businessman who sells dead animals in formaldehyde glass boxes. The over-27,000-square-foot building will serve as the primary London studio for Hirst and headquarters for his company, Science (UK) Ltd, in addition to housing a restaurant at ground level.

Five storeys tall, 40 Beak Street features a number of roof terraces in addition to cornice work designed by Hertfordshire-based artist Lee Simmons. The glazed bricks — “hand dipped” the architects tell us — make for a welcome change from the omnipresence of metal and glass on one end of the spectrum and cheap monotone brick on the other.

The PR hype makes much of bringing a bit of artistic and creative edge back into Soho, a neighbourhood whose final glory days have been depicted in a much-praised book by the Telegraph’s Christopher Howse. We’re not so sure.

Hype aside, 40 Beak Street is an excellent addition to the London landscape and the designers are to be commended for their fine eye for detail. Someone at Stiff & Trevillion knows what they’re doing.

Sunday in Stellenbosch

In recent rambles I came upon an old article from the Spectator in which the late and much-praised Richard West reported from Stellenbosch — “this old and incomparably beautiful town in a valley of vineyards” — on the Sunday after the Dutch Reformed Church renounced apartheid in 1986.

“The students here seem to be confident, cheerful, enthusiastic and full of fun,” West wrote. “Half of them seem to be in love, holding hands and gazing adoringly into each other’s eyes.”

As I walked over the university lawn, I turned at the hoot of a horn, and saw that it came from a motor-bike cop, who wanted to get the attention of and wave to a friend. Small children were paddling in the brook that runs by an avenue of old oaks. Bigger children, spotlessly dressed, went smiling off to their Sunday school, while their elders went to the mother church, where there has been a congregation since 1684. The present building, begun in 1715 and renovated during the 19th century, now has a peculiar boomerang shape so that if you are sitting near one of the ends, you cannot see or hear what is going on at the other side. The church cannot compete in appearance with some of the houses of Stellenbosch, which justify Ruskin’s remark that ‘the only contribution to domestic architecture for centuries was made by the Dutch at the Cape’.

The congregation who filled the church was impeccably dressed, the men all wearing coats and ties, though most women were hatless with summer dresses of normal length at the arms and legs, instead of the 17th-century garb one tends to associate with Calvinism. The congregation has little to do except sing the metrical psalms. The prayers are said by the minister, who devotes much if not most of the hour-long service to giving his sermon. …

Stellenbosch University, which was where apartheid began, is now working to dismantle the system. Whereas the English universities are stuck in the stale polemics of 20 years ago, the Afrikaners are bubbling with radical new ideas. Whereas foreigners once read Afrikaans papers ‘to learn what they were thinking’, it is now essential to read them to find any thinking at all. The two best English newspapers are edited by Afrikaners. The Afrikaners still believe in the future. …

Mr West died in 2015 but it would be fascinating to see what he would make of the Eikestad these days.

Holborn Town Hall

The Metropolitan Borough of Holborn was the smallest borough of London both in geography and population so perhaps it’s not surprising that its town hall was a pretty but rather humble affair. The civic pride and municipal pomposity for which this realm was once renowned are nowhere on show in this handsome building which, but for a few details, could easily be mistaken for a hotel, office building, or private residences.

Holborn Town Hall was built in stages, with the public library on the left-hand side completed in 1894 by the Holborn District Board of Works to a design by Isaacs. With the erection of the borough in 1900, a town hall was needed, and the central and right-hand sections of the building were added between 1906 and 1908 by the architects Hall & Warwick.

In 1965 the borough was merged with St Pancras to form the new London Borough of Camden. It was decided to consolidate the civic government at St Pancras Town Hall, to which the local government union members objected. To placate their ire, a bar for the use of employees was erected atop the annexe being added to the Camden (ex St Pancras) Town Hall — quickly nicknamed ‘the White Elephant bar’.

Though long sold off and converted into office space, the arms of the old borough of Holborn still grace the first floor balcony.

Knickerbocker Spires

Before the age of the skyscrapers, New York’s church spires dominated the horizon and dwarfed their neighbours just like in the medieval towns and cities of the old world — as this photo from the 1900s shows.

Here St Patrick’s Cathedral holds court, with the St. Nicholas Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church poking up a few blocks down Fifth Avenue.

Slightly north on that same boulevard sits the grand renaissance palazzo of the University Club, with the spire of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church poking up behind it.

Inside Governors Island

This intriguing little island in New York Harbour has always held something of a fascination for me — viz. articles previous on the subject. Aside from its interesting history there is the matter of the complete lack of foresight in ending its military use as well as the failure to imagine a future use suitable to its history and, if the word is not hyperbole, majesty.

Gothamist recently featured a new peek inside some of the abandoned buildings on Governors Island, a mere selection of which are reproduced here. (more…)

Hollandic Fever

Adapted from the Deborah Moggach novel of the same name, ‘Tulip Fever’ is a curious concoction. Some of the plot holes are so big you could drive a coach and horses through them. For example, how is it that – in Calvinist-controlled seventeenth-century Amsterdam – there is a massive Catholic convent perfectly accepted by everyone and operating as if nothing is out of place? It’s the size of Norwich Cathedral! (In fact, it is Norwich Cathedral – this entire production was filmed in Great Britain.)

The often excellent Chrisoph Waltz is curiously mismatched with his role here: a little bit too much of a parody of the proud, pious Amsterdam merchant in the start, which makes his eventual transformation a little unconvincing. The plot also shows little of the brilliance of its co-writer Sir Tom Stoppard. (In fact, there’s a bit too much plot.) At least Dame Judi Dench is effortless in her role as the unnamed Abbess of St Ursula. Tom Hollander is thrown in for a laugh, in a role suited to his abilities.

For curiosity’s sake the most interesting casting choice was Joanna Scanlan, known as the useless press officer at DOSAC in ‘The Thick of It’. Here she is the dressmaker Mrs Overvalt, but she was Vermeer’s cook Tanneke in ‘Girl with the Pearl Earring’. If my rudimentary calculations are correct, this means she has been in two-thirds of twenty-first-century films set in the Dutch seventeenth century.

It is, however, a beautifully shot production, for which I suspect we have the cinematographer Eigil Bryld to thank. (He’s worked on one seventeenth-century film before, and on another set in the Low Countries.) Bookended by scenes of Friedrichian romanticism (I’m into that) the film encourages me in my deeply felt belief that we need to revive seventeenth-century Dutch domestic architecture as a style.

Rosary on the Coast

By all accounts last Sunday’s Rosary on the Coast was a resounding success. The initiative started out in Poland, where last year thousands of Catholics gathered at the nation’s borders and coastline to pray for the salvation of Poland and the world. Then a month later Ireland joined in with a Rosary on the Coast for Life and Faith, encircling the country in prayer.

Last Sunday, Great Britain got in on the action, and for three countries which have suffered centuries of Protestant domination it seems we have done rather well on these shores. Thousands of people from every variety of ethnicity, class, background, and experience gathered to pray the Rosary “for the spiritual wellbeing of our nations” (as the organisers put it).

The Rosary on the Coast was organised by lay people but supported by the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster as well as many other bishops and of course priests, many of whom accompanied and led in prayer the lay-organised groups around Britain. The rectors of the three national Marian shrines at Walsingham in England, Carfin in Scotland, and Cardigan in Wales all gave their backing and encouragement to the initiative.

Experience has taught me not to be surprised by the success of such ventures. I remember when the Cardinal renewed the consecration of England & Wales to the Immaculate Heart of Mary (with the visit of the Fatima visionaries’ relics). I didn’t have plans to go but friends were driving in from the West Country for it so I thought I’d meet up with them beforehand and go along.

We tried to get in but the doors of the cathedral were shut and a crowd waiting outside – it turned out the church was packed to the gills with the faithful. A pint later we tried again and they had just reopened the doors and let us in. Every bit of the mother church of the diocese was crammed with people, from Filipino maids to peers of the realm. Pews, aisles, side chapels – there was barely room to move. Priests were hearing confessions and the service was ongoing. We’re so used to being an embattled minority that sometimes we forget that we’re still the biggest show in town.

The good people at the Catholic Herald have collected a variety of photos from around the country, of which just a small sample are presented here. (more…)

The Governor’s Room

Pursuant to my post of John Bartlestone’s photographs of City Hall, I came across this photo the other day and it reminded me that this is still one of my favourite rooms in all New York. There’s something about that particular shade of green. I previously wrote about this suite of three rooms in 2006.

The above photo is by Ramin Talaie while below, in 2010, Mayor Bloomberg inspects a city flag being sent to a New Yorker serving in Afghanistan as reported by the Daily News.

The late & much-missed New York Sun also reported on the portraits hanging in City Hall in 2008.

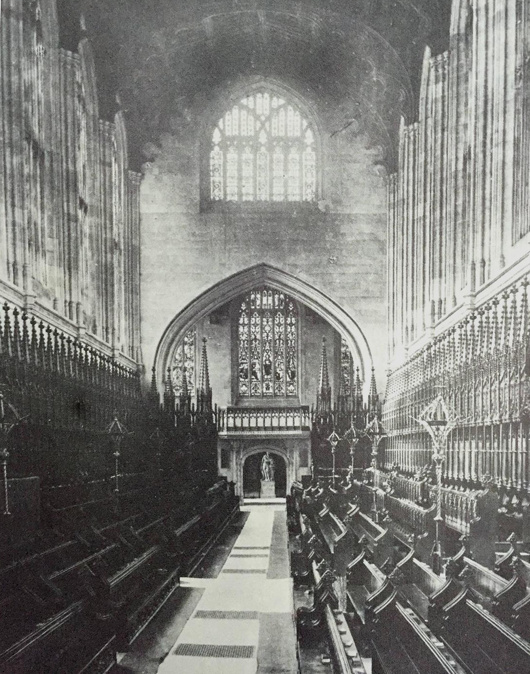

Eton College Chapel

The interior of Eton’s chapel has changed markedly over the past hundred or so years, mostly so thanks to the rediscovery of the priceless medieval wall paintings which had been hidden for centuries by the choir stalls. Painted in the Flemish style in 1479–87, they were whitewashed over by the college barber in 1560 on orders from the wicked new Protestant authorities who had taken over this Catholic school.

The wall paintings were rediscovered in 1847 but it wasn’t until 1923 that the stall canopies in the photograph above were permanently removed, allowing the medieval paintings to be cleaned, restored, and permanently viewed.

In addition to this, in the 1880s (after this photograph was taken) the Great Organ was installed in the broad entrance arch between the narthex and the body of the chapel. The Victorians very handsomely painted it in the medieval fashion and it fits in rather well.

More recently, most of the stained glass was blown out by a German bomb landing in the adjacent Upper School in 1940. A decade later, deathwatch beetles claimed the wooden roof, which was then replaced by fan vaulting (of stone-fronted concrete) in line with the original intentions of Eton’s holy founder, King Henry VI.

Earls, Shires, Hides, and Hundreds

What the Practice of ‘Pricking the Lites’ Tells Us About Territorial Division in Anglo-Saxon England

As cheekily noted by Ned Donovan on his Twitter feed, HM the Q has recently engaged in the old practice of ‘pricking the lites’ to appoint High Sheriffs for the three ceremonial counties of Lancashire, Greater Manchester, and Merseyside. But in order to know what ‘pricking the lites’ is it’s worth looking at the territorial division of Anglo-Saxon England and the old offices that emerged therefrom.

In those days, the land was divided into hides, a hide being the amount of land on which a family lived and supported itself. Ten hides together were known as a tithing, and ten tithings were collectively a hundred.

As hundreds go, the best-known today are the Chiltern Hundreds because of the parliamentary role they play. Members of Parliament are not allowed to resign, but nor are they allowed to hold an office of profit under the Crown.

So whenever an MP wants to resign, he or she is appointed Crown Steward and Bailiff of the three Chiltern Hundreds of Stoke, Desborough, and Burnham and, having accepted such office, is deemed to have disqualified themselves from continuing to sit in the House of Commons. (The Manor of Northstead is also used alternately with the Chiltern Hundreds.)

Anyhow, each hundred was supervised by a constable, and groups of hundreds were collected into shires. Each shire was overseen by an earl, of whom the French equivalent is a count, so after the Normans turned up shires became more often known as counties. These now divvy up territory across the English-speaking world, from Kenya to California.

Each level of these Anglo-Saxon divisions had a relevant court for decision-making, and the officer who administered or enforced these decisions was known as the reeve. Amongst these titles – town-reeve and reeve of the manor, etc. – there was the shire-reeve, or sheriff as it was contracted.

In the 1970s, for reasons unknown to me, all the sheriffs in England & Wales were elevated to high shrievalties.

Every February or March, a parchment is prepared for the Queen in her capacity as Duke of Lancaster with three names of candidates for high sheriff in the three current ceremonial counties covered by the old duchy. This parchment is known as the lites (a cognate of ‘list’, I believe).

At a meeting of the Privy Council, the Queen takes a silver bodkin and pricks the parchment next to the name of the candidate she chooses to be high sheriff. In practice, this is always the first name on the list, and customarily the following names move up a notch and serve in later years.

A similar process takes place for the Duke of Cornwall to appoint their high sherriff but without the aid of the Privy Council.

A Chapel in Bavaria

The Friedhofskapelle, or cemetery chapel, in Herrsching on the Ammersee in Upper Bavaria is a wonderful model of a small church or chapel.

It was designed in 1926 by Roderich Fick, who was a disciple of Theodor Fischer. Herr Fick participated in an expedition to traverse Greenland and joined the German colonial service in Cameroon, after the war moving to Herrsching in 1920.

During the Third Reich he was tasked with redesigning the city of Linz where Hitler had spent his childhood, but the dictator found Fick’s plans somewhat restrained, while Martin Bormann was constantly picking fights with the architect. The dominant style of the regime did not align with Fick’s preference for humble, unpretentious tradition in building design.

After the war he was sentenced to aid in the reconstruction of Munich, and also helped restore the magnificent Town Hall of Augsburg.

City Hall

These images of City Hall show the superb skill and eye for detail of the architectural photographer John Bartelstone — a licensed architect in his own right — and date from the completion of the most recent set of renovations in 2015.

The Port of London

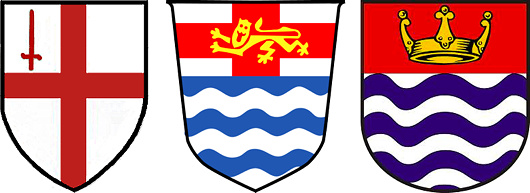

Officially there are or have been various Londons: first the City of London, founded in AD 43 and a mere square mile to this day, then the County of London created in 1889, and the creature called Greater London has also existed in varying shapes and forms since 1965.

But there is also the Port of London, which has existed since the first century and was once the busiest port in the world, bringing the riches of empire to the metropolis from the four corners of the earth.

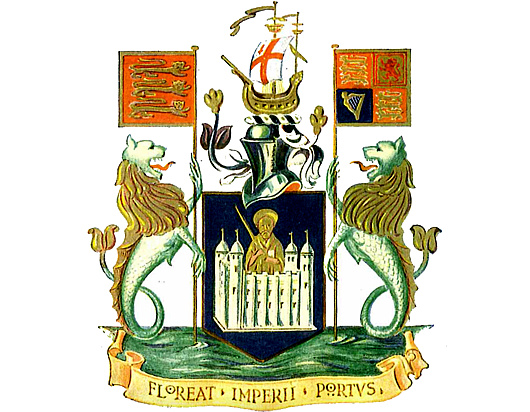

The arms of the City of London, London County Council, and Greater London Council.

All these Londons, of course, have over the centuries been granted or assumed their own coats of arms as heraldic emblems of their importance. The Port of London Authority was created in 1908 by an Act of Parliament which some scholars argue is the first law in the world mandating codetermination or workers’ participation in the board.

Its coat of arms was granted a year later in 1909 and features on its shield Saint Paul, the patron saint of London bearing his usual sword, issuing forth from the Tower of London.

Its coat of arms was granted a year later in 1909 and features on its shield Saint Paul, the patron saint of London bearing his usual sword, issuing forth from the Tower of London.

The crest above the shield is a galley bearing on its mainsail the arms of the City of London — the Lord Mayor is ex officio the Admiral of the Port of London.

Sea lions act as supporters, also bearing standards of the royal arms of England and of the United Kingdom, while the motto proclaims in Latin May the Port of the Empire Flourish.

For proper heraldry nerds, the arms are blasoned:

Shield: Azure, issuing from a castle argent, a demi-man vested, holding in the dexter hand a drawn sword, and in the sinister a scroll Or, the one representing the Tower of London, the other the figure of St Paul, the patron saint of London.

Crest: On a wreath of the colours, an ancient ship Or, the main sail charged with the arms of the City of London.

Supporters: On either side a sea-lion argent, crined, finned and tufted or, issuing from waves of the sea proper, that to the sinister grasping the banner of King Edward II; the to the sinister the banner of King Edward VII.

Befitting the Port of the Empire, the Authority built a grandiose headquarters at 10 Trinity Square, overlooking the Tower of London featured in its coat of arms.

The PLA moved out ages ago and the building is now a hotel, but it often features in films and television as a government (most prominently in the 2012 James Bond film ‘Skyfall’).

The Port of London Authority has its own flag (above) as well as its own ensign — a blue field with a Union Jack in the canton and in the fly a golden sea lion bearing a trident. Distinctive pennants also exist for the Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Authority. (These can be seen here.)

After its foundation the PLA rationalised the layout and organisation of London’s dock system, and their significant constructions allowed the Port to displays its arms on numerous buildings. One such display (above) was recently sold by Westland London.

The main shipping terminal of London is now far down-river at Tilbury and the Authority no longer owns any docks. Its duties however are still numerous — control of Thames ship traffic, navigational safety, pier & jetty maintenance, and conservation — so the century-old Authority still keeps itself quite busy looking after a millennia-old port.

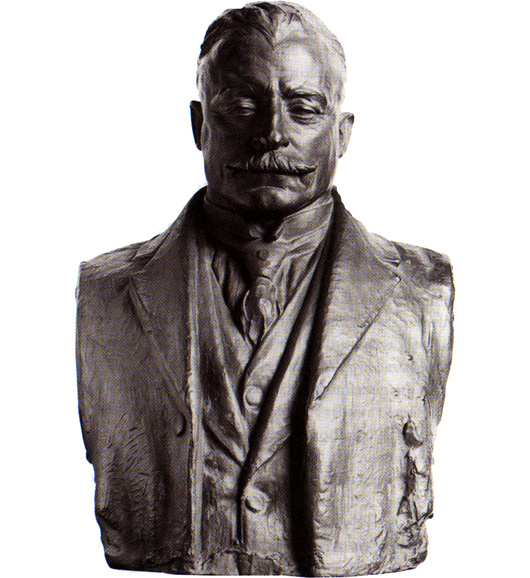

Albert Power & Arthur Griffith

These days the Irish sculptor Albert Power is very rarely spoken of, and I can’t claim to know much about this bronze bust he did of the founder of the original Sinn Féin, Arthur Griffith.

It might be in the National Gallery in Dublin, though I didn’t notice it when I nipped in there with my sister the other day. More likely it is in Leinster House, where there are other busts of prominent figures of 1916-1921 by Albert Power and the better-known Oliver Sheppard.

Unlike Sheppard, Power was a Catholic, which is probably why he was chosen to sculpt the funerary monument of Archbishop Walsh of Dublin who died in 1921. He submitted designs for the new Irish coinage but the Free State wisely chose the far superior set designed by the English sculptor Percy Metcalfe.

As for the subject of this work of art, the Royal Irish Academy’s Dictionary of Irish Biography describes Griffith as “a lucid writer with a vivid turn of phrase”.

The first newspaper he edited was in South Africa where he took the helm of the Middelburg Courant in 1897, attempting to persuade the English-speaking readers with his Boer-friendly views. “I eventually managed to kill the paper,” Griffith wrote, “as the British withdrew their support, and the Dutchmen didn’t bother reading a journal printed in English – the Dutch were quite right.”

Griffith founded Sinn Féin more as a pressure group to support his pet project of reviving the “King, Lords, and Commons” of Ireland, influenced by the Austro-Hungarian Ausgleich of 1867. Independence, he argued, would satisfy the nationalists, while the shared monarchy would keep the unionists happy. In the event, neither half were much enthused by the prospect.

In the aftermath of 1916, Griffith came into his own as a leader and statesman rather than an agitating journalist. His role in the War of Independence and the Treaty negotiations is well known. Without his persuasive arguments in debates, it is highly unlikely the Dáil would have approved the Treaty.

Gloomy civil war soon overshadowed everything, but Griffith died of a cerebral haemorrhage on 12 August 1922 – just ten days before Collins was killed in ambush at Béal na Bláth.

The Steps of the Throne

Who may sit on the steps of the throne in the House of Lords?

Much was made of the Prime Minister’s decision to sit in the House of Lords when they were going through stages of the bill to invoke Article 50 last year. Theresa May had the right to sit on the steps of the throne in the Lords chamber by virtue of being sworn to the Privy Council, as all holders of the four Great Offices of State are (and usually their opposition Shadows as well).

But who else is granted the privilege of lodging their posterior in such a prominent locale?

The Companion to the Standing Orders and Guide to the Proceedings of the House of Lords provides some guidance:

1.59 The following may sit on the steps of the Throne:

· members of the House of Lords in receipt of a writ of summons, including those who have not taken their seat or the oath and those who have leave of absence;

· members of the House of Lords who are disqualified from sitting or voting in the House as Members of the European Parliament or as holders of disqualifying judicial office;

· hereditary peers who were formerly members of the House and who were excluded from the House by the House of Lords Act 1999;

· the eldest child (which includes an adopted child) of a member of the House (or the eldest son where the right was exercised before 27 March 2000);

· peers of Ireland;

· diocesan bishops of the Church of England who do not yet have seats in the House of Lords;

· retired bishops who have had seats in the House of Lords;

· Privy Counsellors;

· Clerk of the Crown in Chancery;

· Black Rod and his Deputy;

· the Dean of Westminster.

Pretoria Philadelphia

Andries Pretorius grew up on his father’s farm near Graaf-Reinet in the Cape of Good Hope, but the Great Trek took him (and many other Boers) into the South African interior. Pretorius’s victory, against all odds, over Dingane’s Zulu forces at Blood River in 1838 was to be commemorated from that day forevermore by Afrikaner piety as Geloftedag — the Day of the Vow. When the South African Republic (ZAR) was established in 1852 the capital was Potchefstroom, but Andries’s son Marthinus founded the city of Pretoria Philadelphia in 1855 to be the new capital of the Transvaal.

The four colonies at the end of the continent were conjoined in 1910 as the Union of South Africa, with Pretoria (as it was soon shortened to) named the seat of the executive and thus the nation’s capital. The parliament met in Cape Town and the highest courts in Bloemfontein so that, in some sense, the new nation had three capitals — administrative, legislative, and judicial. As the seat of the visible sovereignty of the realm, the Governor-General, as well as the Prime Minister’s administration and cabinet, however, it was Pretoria that held precedence.

We’ve already examined Kerkplein — Church Square — at the heart of the city, but the rest of the capital is worth exploring further. (more…)

Lionel Smit

Suid-Afrikaanse portretskilder

Een van die mees geskoolde portretskilders vandag is die Pretoriaanse kunstenaar Lionel Smit (geb. 1982).

’n Skilder en beeldhouer, Mnr Smit woon en werk in Kaapstad en is die wenner van ’n ministeriële toekenning vir bydrae tot visuele kuns van die Wes-Kaapse regering. Sy werk is reeds ingesluit in die visuele kunste eksamen vir die Nasionale Senior Sertifikaat. Nie sleg vir ’n kêrel in sy dertigerjare!

Smit se skilderye herriner my aan die werk van die Engelse skilder Catherine Goodman. Hier is net sommige van sy portrette.

St Paul’s Survives

Crossing the Thames as I walked home from the pub last night, I looked down the river and saw the sturdy dome of St Paul’s standing out, illuminated in the winter night.

As it happens, it was exactly seventy-seven years ago last night — on the 29th of December 1940 — that the iconic photograph often called ‘St Paul’s Survives’ (above) was captured.

Hopeful as that sight must have been, it was a pretty grim time. But four and a half years later (below) the cathedral was illuminated not by the lights of enemy firebombs but by great searchlights forming a massive ‘V’ in the sky: it was 8 May 1945 — Victory in Europe.

Another year gone. We’ve survived.

The McGillycuddy of the Reeks

How lovely to see a member of the Gaelic nobility – in this case, the McGillycuddy of the Reeks – having a letter printed in the newspaper (Daily Telegraph, Letters, Wednesday 20 December 2017).

His title is somehow the most fun of all the Chiefs of the Names, though not all bearers of the chiefdom have found it amusing. In the early years of the BBC, the ‘Green Book’ instructing comedy producers what they could and could not get away with contained the instruction ‘Do not mention the McGillycuddy of the Reeks or make jokes about his name’. Clearly a protestation had been made.

Looking at the map of Kerry on my kitchen wall, the eye often drifts to McGillycuddy’s Reeks themselves, the “black stacks” amongst which can be found Corrán Tuathail, Ireland’s tallest mountain.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories