World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

A Corner in Camberwell

4a-6 Grove Lane by MATT Architecture

Alongside some of its neighbouring streets in Camberwell, Grove Lane has some of the best preserved rows of Georgian houses in south London, interspersed with a few buildings of a more recent vintage. The latest addition to this street is no ostentatious interloper but a contextual classic showing admirable humility and good manners.

Designed by Leicester Square-based MATT Architecture, it’s easy to see why the Georgian Group deemed 4a-6 Grove Lane worthy of a Giles Worsley Award for a New Building in a Georgian Context in 2015.

“The long, thin, wedge–shaped site had lain derelict for decades before being purchased by the current owner,” the architects note.

“The elevation is deliberately split into three to echo the plot width of neighbouring terraces and relies heavily on high quality detailing to lift it beyond pastiche.”

British Columbia in London

Colonial Agents & Provincial Agents-General in the Imperial Capital

JUST WHERE THE elegant Edwardian urbanity of Waterloo Place turns into Regent Street there is an edifice that announces itself as home to the “Agent General for British Columbia”. Built in 1914-1915, it was designed by a not particularly prominent architect named Alfred Burr who did a lot of work for the Metropolitan Police and is also responsible for designing the charming little curator’s lodgings next to Dr Johnson’s House (which he restored 1911-1912).

The listing that protects British Columbia House, at 1-3 Regent Street, describes its style as “rich Baroque with both Roman and Genoese palazzo features composed on a large scale”.

The main entrance is on Regent Street with the province’s delightfully sunny coat of arms carved above the portal, guarded by allegorical figures of Justice and the like above. On the corner with Charles II Street, the inscription on the foundation stone proclaims its laying at the hands of Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught on the sixteenth day of July in 1914.

But who or what on earth was the Agent General for British Columbia? (more…)

The politics of parliamentary colour

When Quebec’s « Salon bleu » was the « Salon vert »

One Westminster tradition replicated in many times and places across the Commonwealth is a convention of colour: the lower house of a parliament is decorated in green, while the upper chamber is decorated in red. This reflects the green benches of the House of Commons and the red ones of the House of Lords.

Officially the plenary chamber of Quebec’s unicameral parliament is boringly the salle de l’Assemblée nationale but because of the colour of its walls it is more often known as the Salon bleu. One’s never surprised when Quebec bucks a trend or (more specifically) rejects an Anglo convention but it turns out the province’s plenary chamber did in fact used to be green until relatively recently.

When the members of the Legislative Assembly (as it then was) first convened in the Hôtel du Parlement in 1886 the walls were actually white. By the opening of the 1895 session the desks had been reappointed in green, but Le Soleil still made reference to the room as the “chambre blanche”. It was only in 1901 that the room was painted a “soft green” and the carpets and other furnishings changed accordingly. It even made an appearance in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1953 film “I Confess”.

From then the chamber was a Salon vert until 1978, when the decision was taken to begin broadcasting the proceedings of the Assemblée nationale.

The television specialists complained that the dark green of the chamber was not visually conducive to the TV cameras available at the time and, looking at the evidence from the 1977 test session (above), one can see their point. Walls of either beige or blue were the options recommended in an official report, and unsurprisingly the national colour was chosen.

The historian Gaston Deschênes has mentioned the technical requirements of broadcasting also coincided with a desire to break with a “British” tradition. Certainly the government of the day, René Lévesque’s Parti Québécois, didn’t mind the change, while Maurice Bellemare — “the old lion of Quebec politics” and sometime leader of the old Union nationale — was deeply pleased that the chamber adopted the colour of Quebec’s flag.

So the walls were repainted sky blue and the furnishings changed accordingly, resulting in the Salon bleu we know today (below).

A tweet from the Assemblée’s official account shows two photos looking towards the chamber’s entrance from before (above) and after (below) it was made ready for television.

All the same, green is not universal amongst Commonwealth lower (or only) chambers. It’s not even universal in Canada: Manitoba joins Quebec in its azure tones while British Columbia’s is red-dominated.

Quebec was the last of Canada’s provinces to abolish its upper house, the Legislative Council, in 1968 (at the same time the lower house was renamed the National Assembly). The Legislative Council’s former meeting place is, of course, red, and the Salon rouge is used for important occasions like inductions into the Ordre national du Québec or the lying-in-state of the late Jacques Parizeau.

Angela Wrapson

In Rome the other week I was sorry to hear from a mutual friend that Angela Wrapson had died. She had been fighting cancer for a while, but she was quite a fighter and was one of those people you thought would always go on.

Angela was, amongst many things, a fixture of that strange yet familiar galaxy known as the Scottish arts world. She was, for example, director of the Stanza poetry festival for some years.

She was a keen listener, a good conversationalist, and a very welcoming hostess in the wing of Brunstane House that she and her husband George bought back in the 1970s.

From 2015 to 2017, George was the MP for East Lothian and I am still ashamed in those two years I never managed to reciprocate Angela and George’s hospitality by having them round.

Nonetheless, I was pleased to see she got the plaudits she deserved with obituaries in the Scotsman, the Times, and the Herald.

May she rest in peace.

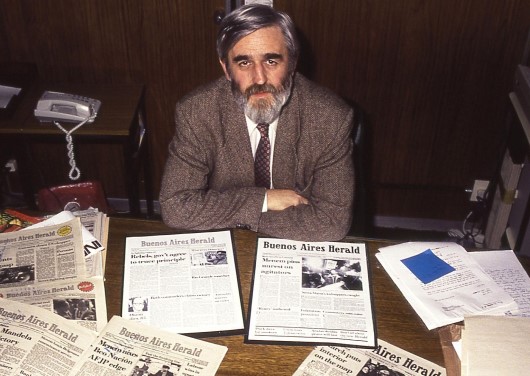

Andrew Graham-Yooll

A giant of Argentine journalism died this summer: Andrew Graham-Yooll.

Born in Buenos Aires early in 1944 to a Scottish father and an English mother, Graham-Yooll made his name at the premier institution of Anglo-Argentina, the now-defunct daily Buenos Aires Herald which he joined aged 22 in 1966.

“The Herald newsdesk supped for Dutch courage a local brandy,” the Times notes, “supplemented with a pâté that Graham-Yooll made of goose livers lashed with gin. A chain-smoker, he would construct tiny houses from matchsticks.”

As the Herald’s news editor during Isabel Perón’s presidency he published the names of dissidents who had gone missing or “disappeared” and, more bravely, continued to do so after Señora Perón was succeeded by a military junta.

The new rulers, who Borges warmly welcomed as “gentlemen”, put Graham-Yooll on trial for publishing interviews with the guerrillas who were terrorising the country. He was acquitted, but accepted the gentle advice of the judge who suggested he might find existence more comfortable outside the borders of the Argentine Republic.

Graham-Yooll continued writing for the Daily Telegraph and Guardian in Great Britain but made a brief foray home in 1982 during the Falklands War before being permanently welcomed home by a democratic government in 1984. Ten years later he was appointed editor of the Herald.

“Things you think you can rely on and trust are just not there,” Graham-Yooll said in Edinburgh when picking up his OBE in 2002.

“You can’t trust the bank, you can’t trust the post office or the people who sell you a house. You can’t trust the politicians, obviously. It’s a friendly society but it lacks strict rules. It’s evil, but it is also attractive to live in a place where you don’t have to live by rules.”

“I don’t know where I could go now. It was always home, even in the worst days, and it still is.”

Four Reasons Rodden and Rossi are Wrong on Northern Ireland

Economics alone will not join what history has rent asunder

Academics John Rodden and John Rossi have an interesting but poorly argued piece in the normally-quite-good American Conservative “asking” the question of whether Brexit could unite Ireland at last. While ostensibly they merely posit the question, they lay out an unintended-consequences scenario for Irish political unity coming about.

If Brexit goes “wrong” then the imposition of a hard border in Ireland will drive Northern Ireland’s Protestant/Unionist community into the arms of the Republic. If there’s no hard border, then Northern Ireland and the Republic will progress down a path of natural economic integration while, Rodden and Rossi argue, “economic divergence from Britain with no hard border will show northerners that their long-term interests now lie with Dublin”.

There are some obvious problems with the Rodden/Rossi scenario.

First, the EU’s customs and economic union has already applied to Northern Ireland and the Republic for decades now and yet Northern Ireland is not economically integrated into the Republic. Of goods that leave Northern Ireland, the rest of the UK is still the strongest destination: In 2016 £10.5 billion of goods left NI for Great Britain, compared to £2.7 billion to the Republic.

True, Ulster is more vulnerable in that a bigger chunk of their exports head south of the border than the Republic’s exports head north of it. But after decades of trade barriers being torn down by the EU these two economies remain very much distinct.

Second, Rodden and Rossi fall into the trap of economic determinist thinking. The roots of Republic of Ireland/Northern Ireland divide are not economic. Ireland’s six north-easterly counties were excluded from the Irish Free State in 1921 because of the tribal fears of those counties’ Protestant/Unionist majorities of being powerless in a state that would have an overwhelming Catholic/Nationalist majority. Some of these fears were well-reasoned and considered, others were wildly irrational and bigoted.

The important thing to realise is that the divide between Nationalists and Unionists is not formed on the basis of economic arguments, though either side can deploy economic arguments in their favour. It is simply not the case that a significant chunk of Northern Ireland’s Protestant Unionist community are going to wake up some day soon and think “Well, I’ve always liked our Union Jacks, Orange marches, and devotion to the Queen but Northern Ireland might be able to achieve a 2.3% better rate of growth if we join the Republic so I’ll run up the tricolour and paint my curbside green, white, and orange”.

Third, as Rodden and Rossi confusingly point out, the coming demographic majority Catholics will achieve in Northern Ireland does not automatically equate to all-Ireland unity: An astonishingly large proportion of Northern Irish Catholics wish to maintain links to the United Kingdom. They will continue to vote for Sinn Féin and the SDLP in elections because these parties are viewed as those who vie to look after their community’s interests. But that does not necessarily mean they want to cut all ties to the UK or sign up for a 32-county unitary republic.

“Ah!,” they say. “But hard Brexit!” This is the fourth point why Rodden and Rossi are wrong. They argue that a hard Brexit would necessitate a hard border with the imposition of frontier infrastructure, tolls, taxes, etc. Rodden and Rossi claim that “[t]he only workable plan for Brexit that will prevent a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic is for the north to stay in the EU customs area despite Brexit.”

This is simply not true. By now almost everyone has conceded, including civil servants in both London and Dublin, that even in the event of a No Deal Brexit (which has pretty much been ruled out) the technology already exists to provide a fairly seamless border. The few companies whose cross-border trade would fall into the relevant categories could be checked not at the border but electronically. While anti-Brexiteers spent months arguing that this was an impossible pipe dream, the number of researchers, customs agents, civil servants, and others who point out that the technology exists and has been used in similar scenarios for years is now so voluminous as to render the argument irrelevant.

(Rodden and Rossi are also entirely incorrect in claiming that Northern Ireland has adopted “quite restrictive” laws on “abortion and gay rights”. In fact, Northern Ireland’s post-1998 democratically elected representatives have mostly decided against taking action to change existing laws on these subjects even though they have been altered or repealed in England, Wales, and Scotland.)

There are other problems with the Rodden/Rossi economic determinist case for a united Ireland. For one thing, there is an economic determinist argument against it. The Republic of Ireland is a relatively prosperous country, though obviously not without its problems. Though romanticism and patriotism have deep roots, the Republic’s taxpayer base might balk at taking on the highly subsidy-reliant Northern Irish economy, even if only with a mind to transitioning it to a more free-market scenario.

Furthermore, sources in the Irish Defence Forces are quick to express their anguish at the army’s much diminished capacity even to carry out its existing commitments with the United Nations. Northern Ireland separating from the United Kingdom and joining the Republic would almost certainly spark a revival of violence amongst a minority of the province’s loyalists. Are voters in the Republic really that keen to take on an economic and counter-terrorist burden?

All this may sound a bit Cassandra-like, especially coming from a writer with traditional “Up Dev” Fianna Fáil sympathies, but these are all factors that need to be considered and which significantly inhibit the likelihood (completely separate from the wisdom) of Irish political unity in the near future.

What do Namibians know of Germany?

Namibia spent more than twice as long under South African administration then it did when it was German South West Africa, but its formative years under the Germans continue to have an influence.

For one thing, you can stumble around streets marked Zeppelinstraße and Bismarckstraße, not to mention the quite quaffable beer the country produces. Germany’s most remembered act in Namibia, alas, is the massacre of the Herero tribe, whose women are today known for their colourful pseudo-Victorian traditional dress.

Still, a third of the country’s white population are of German descent and German was an official language until 1990, though Namibian Black German (which linguists debate whether it is a dialect or a pidgin) is now nearly extinct. Most German Namibians today would speak Afrikaans on an everyday basis and have a strong grasp of English too.

But what does the average Namibian on the street know of Germany? In the above video a man goes about asking precisely that. Particularly interesting is that moneyed Frankfurt seems to be much better known than the political capital of Berlin. If only there was a video asking Germans what they know of Namibia…

The Rensselaer Window

The patroonship of Rensselaerswyck was erected in 1630 giving its patroon, Kiliaen van Rensselaer, feudal powers over a large parcel of land on the banks of the Hudson River. Despite exercising a strong influence on the growth and development of New Netherland and the Hudson Valley, Kiliaen never actually stepped foot in the new world but kept close control of his domain from across the ocean in Amsterdam.

Jan Baptist was Kiliaen’s second surviving son, and served as director at the ‘colony’ as it was often known from 1652 to 1658. He commissioned Evert Duyckinck to make this painted-glass window displaying his coat of arms in 1656 and gave it to the Dutch Reformed Church in Beverwyck (today’s Albany).

While the congregation still exists — and celebrated its 375th anniversary in 2017 — the original church was demolished in 1805 and the window moved to the Van Rensselaer Manor House which itself survived til 1890 before facing the wrecking ball. The window was preserved and was left to the Metropolitan Museum of Art through the 1951 bequest of Mrs J. Insley Blair and while well documented it does not appear to be on display at the moment.

The patroonship itself was converted into a manorial lordship by the English authorities after they took over and survived until it was broken up amongst relatives after the death of Stephen van Rensselaer III in 1839.

This last great patroon had proved an indulgent lord and the efforts of his inheritors to claim uncollected back rents led to the 1839-1845 “Helderberg War” or “Anti-Rent War” of tenants revolting against the system. The great landholders, seeing the end was nigh, were convinced to sell up and in 1846 the state of New York adopted a new constitution abolishing feudal tenure. The era of patroonships and manors in the Hudson Valley had come to an end.

The Feast of St Valentine in the Cape

Die fees van Sint Valentyn in die Kaap

A nice tradition!

’n Lekker tradisie!

Letter to the Editor: The Times

There has been a distinct increase in the number of missives sent out from Huis Cusack to editorial offices across Europe and beyond as part of my slow but inevitable transformation into “Disgruntled of Tunbridge Wells”. It all started with an extremely pedantic letter to the TLS regarding PG Wodehouse, banking, and the collapse of the rupee that was printed in October 2008.

It escaped my notice at the time but it turns out the editors of The Times of London were short of anything decent to print last November so stuck one of my letters in. Very kind of them.

Sir, There is a parallel to the situation of Britons involuntarily losing their EU citizenship: the unionists who fell on the southern side of the border when Ireland was partitioned in 1921. Like the British in Europe today, many Irish then felt themselves secondarily or primarily British or at least strongly associated with Great Britain, given the unitary state which had existed for more than a century. More Irish volunteered their service and their lives for the British crown than ever did for an Irish republic.

As an Irish citizen resident in the UK I appreciate the generosity of spirit whereby Ireland is not a “foreign” country. Irish in Britain today have full civil and political rights above and beyond those of other EU citizens, and this is reciprocated in the Republic (except for presidential elections and referendums).

Were the EU to extend such generosity and reciprocity to the UK after Brexit it would go a long way to furthering our common identity and friendship.

ANDREW CUSACK

London SW3

Of course I am as poblachtánach as anyone else — Up Dev and all that — but one does appreciate the difficulty of those Irish who also identified as British once the Free State was erected. But then given my background (Irish New Yorker educated there, in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa, resident in London) I don’t see any problem with a multiplicity of overlapping identities. All the same, when people imply they will somehow mystically cease to be European come 29 March it just makes them look silly. Great Britain has always been a European country and always will be.

I blame Ulster, the French Revolution, and the Fall of Man.

Neo-Classical New York

The dome of the old Police Headquarters Centre Street in New York.

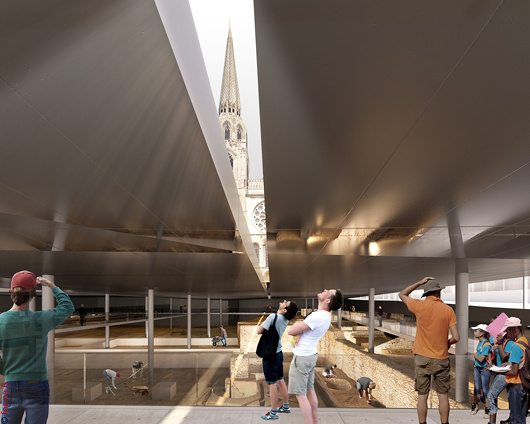

Chartres Disfigured

Plans for modern monstrosity in venerable cathedral’s forecourt

MORE BAD NEWS from Chartres. Fresh from the completion of a controversial and much criticised renovation of the ancient cathedral’s interior, le Salon Beige reports the city has unveiled plans to tear up the parvis in front of the cathedral and replace it with a modernist “interpretation centre”.

The original parvis (or forecourt) was much smaller than the one we know today. Between 1866 and 1905 the majority of the block of buildings in front of the cathedral, including most of the old Hôtel-Dieu, were demolished to give a wider view of the cathedral’s west façade and its “Royal Portals”.

After the war various plans to tart the place up were made and variously foundered — from a modest alignment of trees in the 1970s to Patrick Berger’s plan for an International Medieval Centre. More recently the gravelly space was unsuccessfully “improved” by the addition of boxes of shrubbery placed in a formation that, jarringly, fails to align with the portals of the cathedral.

The proposed “interpretation centre” designed by Michel Cantal-Dupart — at a projected cost of €23.5 million — destroys the gentle ascent to the cathedral and indeed reverses it. At a projected cost of €23.5 million, a giant slab juts apart as if displaced by an earthquake. The paying tourist is invited down into its infernal belly while others prat about on the slab’s upwardly angled roof, ideal for gawking at the newly commodified beauty of this medieval cathedral. It is practically designed for Instagramming, rather than reflection and contemplation.

As you would imagine, reaction has been strong. Michel Janva, writing at le Salon Beige, says the project “plans to imprison the cathedral” and “will disappoint not only pilgrims on their arrival, but also inhabitants and tourists”.

In the Tribune de l’Art, Didier Rykner is damning: “All this is purely and simply grotesque.” The sides of the centre, he points out, will be glazed to allow in natural light, but this will both interfere with multimedia displays and be bad for the conservation of fragile works of art. “This architecture, which looks vaguely like that of a parking lot, is frighteningly mediocre, and this in front of one of the most beautiful cathedrals of the world.”

Rykner attributes blame for the “megalomaniac and hollow project, expensive and stupid” at the doors of the mayor of Chartres, Jean-Pierre Gorges, who he argues has allowed much of the rest of the city’s artistic and architectural heritage to go to rot while devoting resources to this pharaonic endeavour.

Having walked from Paris to Chartres myself I can imagine how much this proposal will injure the experience for pilgrims. After three days on the road, to arrive at Chartres, stand in the parvis, and gaze up at this work of beauty, devotion, and love for the Blessed Virgin is a profound experience. If constructed, this plan would deprive at least a generation or two from having this experience. (But only a generation or two, for it is simply unimaginable to think this building will not be demolished in the fullness of time.)

Chartres is part of the patrimony of all Europe and one of the most important sites in the whole world. For it to be reduced to the plaything of some momentary mayor is a crime. With any luck, the good citizens of Chartres, of France, and of the world will put a stop to this monstrosity. (more…)

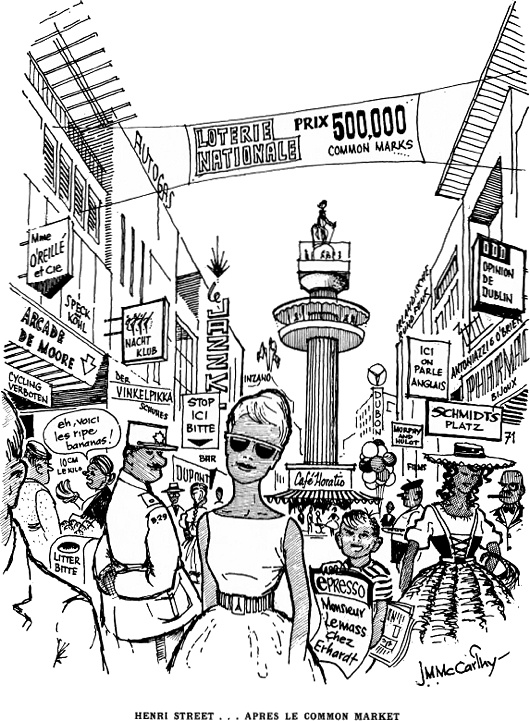

Dublin in the Common Market

A full decade before Ireland joined the E.E.C., cartoonist J.M. McCarthy filed this vision of the Irish capital’s cosmopolitan future in a 1962 issue of Dublin Opinion.

The scene is Henry Street — renamed “Henri” of course — leading up to Nelson’s Pillar in O’Connell Street and the wags show dear old dirty Dublin transformed into a polyglot European capital.

Advertisements and shop signs are in every language (except Irish), the Gardaí have adopted a képi as their headgear, the currency is the “common mark”, and a stylish young woman with bare arms steals the show and sets the tone.

The European Economic Community finally admitted Ireland as a member in 1973, by which time Nelson had be blown up and Dublin Opinion ceased publication.

More Dutch Flags of New York

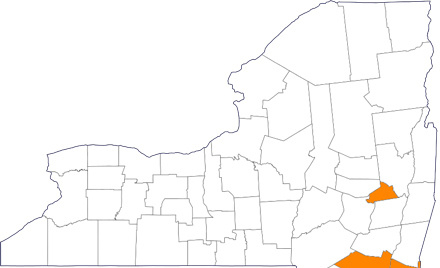

Areas shaded in orange are the counties of New York with Dutch-influenced flags

Natives and outsiders alike are often surprised when it’s pointed out just quite how much New York continues to be influenced by its Dutch foundation to this day, even though Dutch rule ended in the seventeenth century.

Previously I explored a number of local or regional flags in the state of New York that show signs of Dutch influence: those of the cities of New York and Albany, the Boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens, and the counties of Westchester, Nassau, and Orange.

I’ve since found a few more counties to add to our survey of Dutch flags in the Empire State.

Dutchess County

One of the original counties of New York established in 1683, Dutchess retains the archaic spelling of Mary of Modena’s title while she was Duchess of York. Appropriately for a county that was until very recently largely agricultural, the county seal depicts a sheaf and plough, and sits on the county’s flag with its horizontal tricolour of orange, white, and blue.

Ulster County

Across the Hudson from Dutchess County is Ulster, another of New York’s first counties. Its handsome seal features an early farmer wielding a sickle in front of a sheaf and a farmhouse, with the year of the county’s erection proudly included. The Dutch had begun to trade here as early as 1614, and the village of Wiltwijck was given municipal status by Peter Stuyvesant in 1663. Wiltwijck became Kingston in 1669 and remains a very handsome town today.

Schenectady County

The county of Schenectady is of later origin, 1809, and became industrialised in the latter half of the nineteenth century — the General Electric Company was founded here in 1892. Like Ulster and Dutchess, the county flag is just the seal displayed on an orange-white-blue tricolour.

The seal is a relatively boring depicting of crossed swords combined with the scales of justice, but on the flag it is depicted with a locomotive, canal boat, broomhead, and lightning bolt and atom.

Happy New Year

The castle at Český Krumlov (or Krummau) in southern Bohemia, as photographed in winter by Libor Sváček.

Secret Splendor

by Andrew Cusack (Weekly Standard, 13 September 2010)

Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic

by Xander van Eck

Waanders, 368 pp., $100

This book is the first major overview and exploration of the art of the clandestine Roman Catholic churches in the Netherlands. It is not a study of paintings so much as a history in which art is like the evidence in a detective story, or perhaps even the characters in a play. It might seem extraordinary that there was a place for large-scale Catholic art during the Dutch Republic: Pre-Reformation churches had been confiscated and were being used for Calvinist services, while priests offered the Mass secretly in makeshift accommodations. Eventually a bargain between Dutch Catholics and the civil authorities emerged, trading Catholic nonprovocation in exchange for private toleration of the practice of the faith. Catholics began to purchase properties which, for all outward appearances, maintained the look of ordinary residences but whose interiors were transformed into resplendent chapels and churches.

Xander van Eck provides verbal portraits (often accompanied by contemporaneous painted ones) of several of the important clerics of the Dutch church during this period: Sasbout Vosmeer, the Delft priest influenced by St. Charles Borromeo; Philippus Rovenus, the vicar-apostolic who placed greater emphasis on clandestine parishes having specially dedicated churches, even while they kept an outward unecclesiastical appearance; and Leonardus Marius, the priest who promoted devotion to the 14th-century Eucharistic “Miracle of Amsterdam.” Marius was of such prominence that, after his death, shopkeepers rented out places on their awnings for punters to view his funeral procession. Van Eck includes a handful of amusing asides, such as the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Netherlands as a result of their constant discord with the secular clergy. Mass continued to be offered at the Jesuit church of De Krijtberg in Amsterdam “in the profoundest secrecy” — thus creating a clandestine church within a clandestine church!

The role of the clergy in sustaining the Dutch Church is unsurprising, but it is instructive to learn how instrumental laity were to keeping alive the light of Catholic faith in the Netherlands at the time. Clandestine churches relied on the generosity of Catholic families. Prominent families often provided their own kin as consecrated virgins who brought large dowries into the church, or as priests with suitable inheritances to maintain or endow clandestine parishes. The clandestine church of ’t Hart in Amsterdam, built by the merchant Jan Hartman for his son studying for the priesthood, is still open today as the Amstelkring Museum and Chapel of “Our Lord in the Attic.”

While van Eck explores the extent to which Dutch art from the period followed European norms, an emphasis on the particularity of the art of the clandestine church is to be expected. The sheer volume of art produced during this period — for just three Amsterdam churches alone there were 16 altarpieces — is partly explained by the phenomenon of “rotating altarpieces.” The paintings above the altar would be changed according to the feast or season — a practice sometimes seen in Flanders or parts of Germany but never nearly so widespread as in the Netherlands proper.

Constrained as clandestine churches were on the narrow plots typical of Dutch cities, there was no room for side chapels that might include the large funerary monuments prominent families would construct. This left altarpieces as the most convenient way for munificent Catholics to provide art for their churches: Rotating the altarpieces provided a handy way of displaying numerous commissions rather than just the donation of whoever had been generous most recently, and the themes of these commissions tended to vary in appropriateness to different feasts and seasons.

Some found fault with this method: Jean-Baptiste Descamps, visiting Antwerp in 1769, complained that the most interesting altarpieces were not permanently displayed and were more likely to be damaged in the process of being moved so often.

While the accomplishment and ingenuity of Dutch Catholics in keeping their faith during the Republic was striking, the ill-defined administrative structure of the persecuted church allowed conflicts between clerics to thrive, and doctrinal disputes emerged and festered. The disputes over Jansenism that swept over France and the Netherlands, for example, only exacerbated the administrative problems of the clandestine church. Like their Calvinist compatriots, the Jansenists tended to frown on indulgences, the veneration of saints, recital of the rosary, and private acts of worship, putting greater emphasis on the Scriptures and a more rigorous asceticism. As van Eck points out, this difference in emphasis was not exclusive to the Jansenists, but their novelty (and their heresy) was in preaching the exclusivity of their approach above all others.

Numerous vicars-apostolic had written to Rome arguing for the re-establishment of the episcopacy in the Netherlands to solve the disputes over authority, but their appeals fell on deaf ears. In 1723 a large portion of the Jansenist clergy reinstituted the episcopacy by electing an archbishop of Utrecht from their number — and were subsequently excommunicated, splitting the clandestine church and its clergy in two. (This excommunicated rump united with the opponents of papal infallibility in the following century to form a body that still calls itself the Old Catholic Church.)

When one looks at all this glorious art, not to mention the lives and pious ingenuity of the persecuted, it’s difficult not to feel a little poorer, considering the fruits of our churches in an ostensibly free era. Why does the church today commission painters who are either mediocre or trendy — or both? Artists like Hans Laagland and Leonard Porter show that good art — good liturgical art, even — is possible today, but commissions from the church for traditional artists are sadly few.

Roots and Permanent Interests

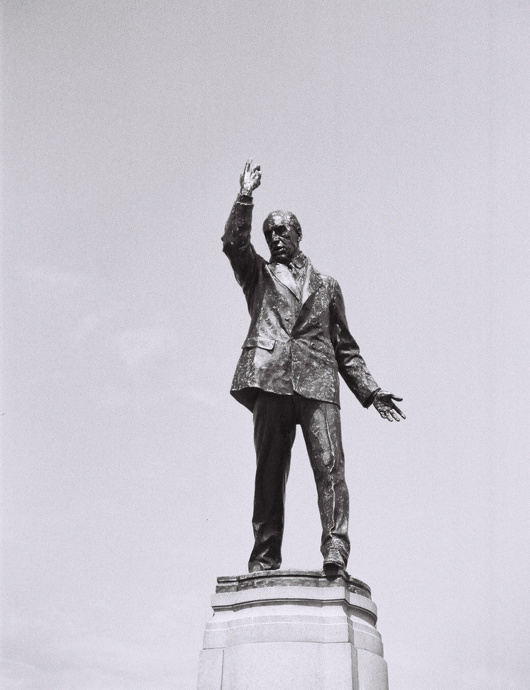

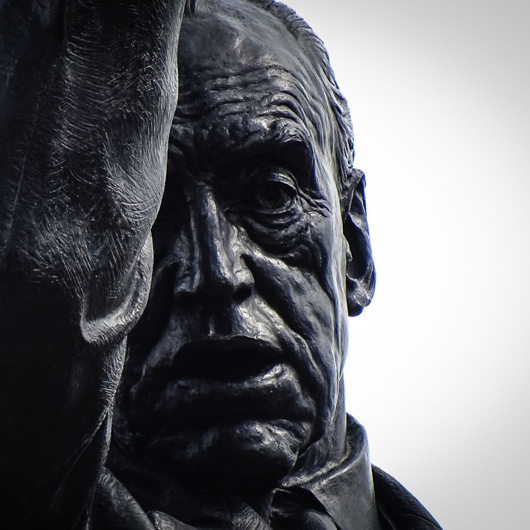

Carson at Stormont

Few statues in Ireland are as dramatic as that of Edward Carson at Stormont. The unionist leader is depicted in amidst an oratorical flourish, doubtless in one of his speeches to mass meetings condemning home rule.

In the 1910s as the rebirth of an Irish parliament looked more likely, Carson took up the cause of fighting home rule on behalf of Ireland’s large Protestant minority who feared Catholic domination. When the anti-home rulers realised the cause was losing, they retreated from Irish unionism to Ulster unionism. If home rule was to be granted, Ulster must be exempted. In the end this meant home rule was granted to a parliament covering two-thirds of the Irish province of Ulster — six counties that would henceforth be known as Northern Ireland.

“His larger than life-size statue,” one historian wrote, “erected in his own lifetime in front of the Northern Ireland parliament at Stormont, symbolizes the widely held perception that Northern Ireland is Carson’s creation.”

This is of course the great irony, given that Edward Carson was a Dublin boy through and through. While instrumental in ensuring northeastern Ireland’s exemption from an Irish parliament, Carson actually had little to do with the entity thereby created. When offered the premiership of Northern Ireland he declined it on the grounds of having no real connection with the place.

Craig, not Carson, is the true father of Northern Ireland; he imbued the new statelet with a sense of bigotry and tribal hatred that Carson lacked. The Dubliner urged Ulster’s new leaders to treat the province’s Catholics well.

“We used to say that we could not trust an Irish parliament in Dublin to do justice to the Protestant minority,” Carson said. “Let us take care that that reproach can no longer be made against your parliament, and from the outset let them see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from a Protestant majority.”

Alas, it became apparent to Carson that discrimination and inequality were becoming in-built within Northern Ireland’s government, from the Parliament at Stormont down to the lowest forms of local government. He confided to a Catholic friend in London that rather than being an integral part of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland was turning into “a second-class dominion”.

After partition Carson was created a British judge and accordingly ennobled. (Disappointingly the plaque on his Dublin birthplace next to Conradh na Gaeilge refers to him by the incorrect style of ‘Lord Edward Carson’.) He settled at Clever Court near Minster-in-Thanet, Kent, and never lived in his native Ireland again.

Nonetheless he was held in awe and reverence by the Protestant Unionists of Ulster, who commissioned the striking statue by Leonard Stanford Merrifield that stands in front of Parliament Buildings, Stormont — now home to the Northern Ireland Assembly. It was unveiled by Craig, by then ennobled as Lord Craigavon, while Carson was alive and present in July 1932, joined by a crowd of 40,000 well-wishers.

Carson died in 1935 and was given the rare honour of a state funeral. HMS Broke brought his Union-Jack-draped coffin back to Ireland — albeit to Belfast — and he was interred in the Anglican Cathedral of St Anne. Northern Ireland claimed him even in his final burial: soil from each of its six counties was scattered on his coffin when laid to rest in the tomb.

Still his statue stands at Stormont, gesturing stridently as if to challenge an entire province — a province he by his own description had little to do with. Calls for it to be removed emanate occasionally from typically boring quarters and have so far been rebuffed — wisely. Carson, unlike many of those who cherished his memory, was an honourable man, and it is a pity it took so long for the Protestants of Ulster to heed the advice of their confrère from Dublin.

St Nicholas, Our Patron

As by now you are all well aware, today is the feast of Saint Nicholas, the patron-saint of New York. His patronship (patroonship?) over the Big Apple and the Empire State date to our Dutch forefathers of old – real founding fathers like Minuit, van Rensselaer, and Stuyvesant, not those troublesome Bostonians and Virginians who started all that revolution business.

Despite being Protestants of the most wicked and foul variety, the New Amsterdammers and Hudson Valley Dutch maintained their pious devotion to the Wonder-working Bishop of Myra and kept his feast with great solemnity.

After New Netherland came into the hands of the British (and was re-named after our last Catholic king) the holiday continued to be celebrated by the Dutch part of the population, and was greatly popularised in the early nineteenth century by the publication of a curious volume entitled A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty which purported to be by one Diedrich Knickerbocker.

In fact it was by Washington Irving, the first American writer to make a living off his pen, who did much to popularise St Nicholas Day in New York as well as to revive the celebration of Christmas across the young United States.

While, aside from hearing Mass and curling up with a clay pipe and a volume of Irving (being obsessive, I have two complete sets) here are a few links that shed some light on New York’s heavenly protector.

Historical Digression: Santa Claus was Made by Washington Irving

New-York Historical Society Quarterly: Knickerbocker Santa Claus

The History Reader: The 18th Century Politics of Santa Claus in America

The New York Times: How Christmas Became Merry

The Hyphen: Thomas Nast’s Illustrations of Santa Claus

– plus: Santa Claus and the Ladies

National Geographic: From Saint Nicholas to Santa Claus

Previously: Saint Nicholas (Index)

Dolosse

dolos, pl. dolosse

Visitors to the seaside and frequenters of port cities will be familiar with those oddly shaped concrete forms which are dropped together to form breakwaters and prevent erosion.

It turns out that they have a name of Afrikaans origin: dolos (plural dolosse).

‘Dolos’ is believed to be a contraction of ‘dollen os’, the name for the children’s toy of knucklebones or jacks. This particular shape was invented by Aubrey Kruger and Eric Mowbray Merrifield to rebuild the revetments of East London’s artificial harbours following the great storm of 1963.

Kruger fashioned a smaller version of the shape to show his idea to Merrifield, and legend has it that Kruger’s father visited them on the quayside and asked Wat speel julle met die dolos? (‘What are you playing at with the jack?’) The name stuck.

In 2016 the South African Mint released a two-rand ‘crown’ coin depicting the dolos as a tribute to this example of South African ingenuity.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories