World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Septuagesimo Uno

Septuagesimo Uno is often believed to be the smallest park under the purview of the Parks Department of the City of New York. It’s not. (By my reckoning, the Abe Lebewohl Triangle where Stuyvesant Street meets 10th Street near St-Mark’s-in-the-Bowery is the smallest.)

Though not the smallest, this park on West 71st Street is charming all the same. The site was acquired in 1969 thanks to Mayor Lindsay (or “Lindsley” as my maternal great-grandfather always mispronounced his name) and his Vest Pocket Park initiative. The small building on the lot was condemned and demolished by the City though it was only handed over to the Parks Department in 1981.

Originally known as the “71st Street Plot”, Parks Commissioner Henry Stern thought the name was too boring so rechristened it under the Latin moniker Septuagesimo Uno — Latin for ‘seventy-one’. (more…)

A Scene in Buenos Aires

A hatted woman sits on a balcony, looking away out over the Plaza de Mayo, the Cathedral of Buenos Aires, and the city beyond.

It looks like the sort of thing taken by one of the French photographers, but in fact it is by a total amateur: Henry Dart Greene, the son of the Californian architect Henry Mather Greene (of Greene & Greene).

From 1928 to 1931, Dart Greene worked for the Argentine Fruit Distributors Company, founded by the Southern Railway to make use of the individual smallholdings long its line.

Upon his death, Dart Greene’s papers were deposited in the library of the University of California at Davis including this photograph from his time in Argentina.

While the building it’s taken from has been demolished and replaced with a bank, most of what you see beyond is still there.

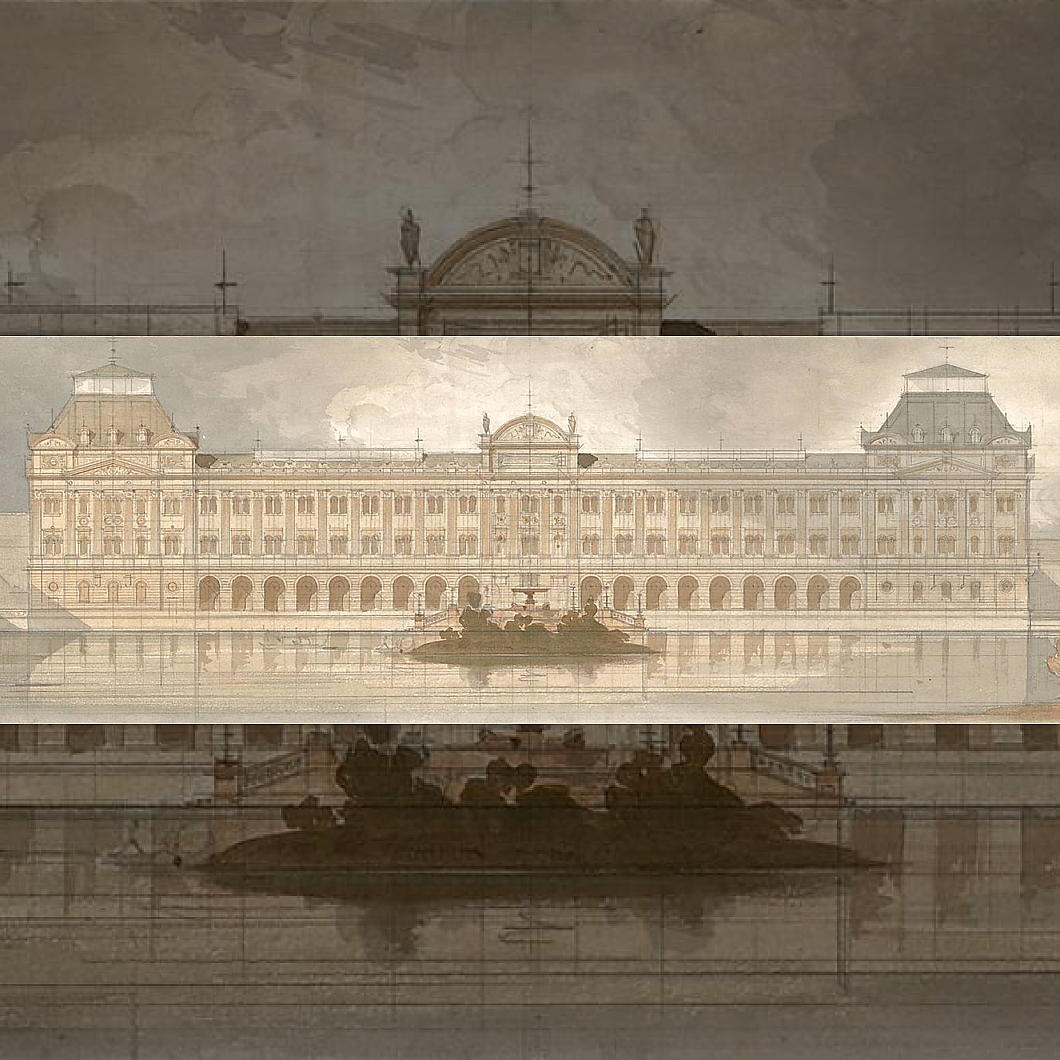

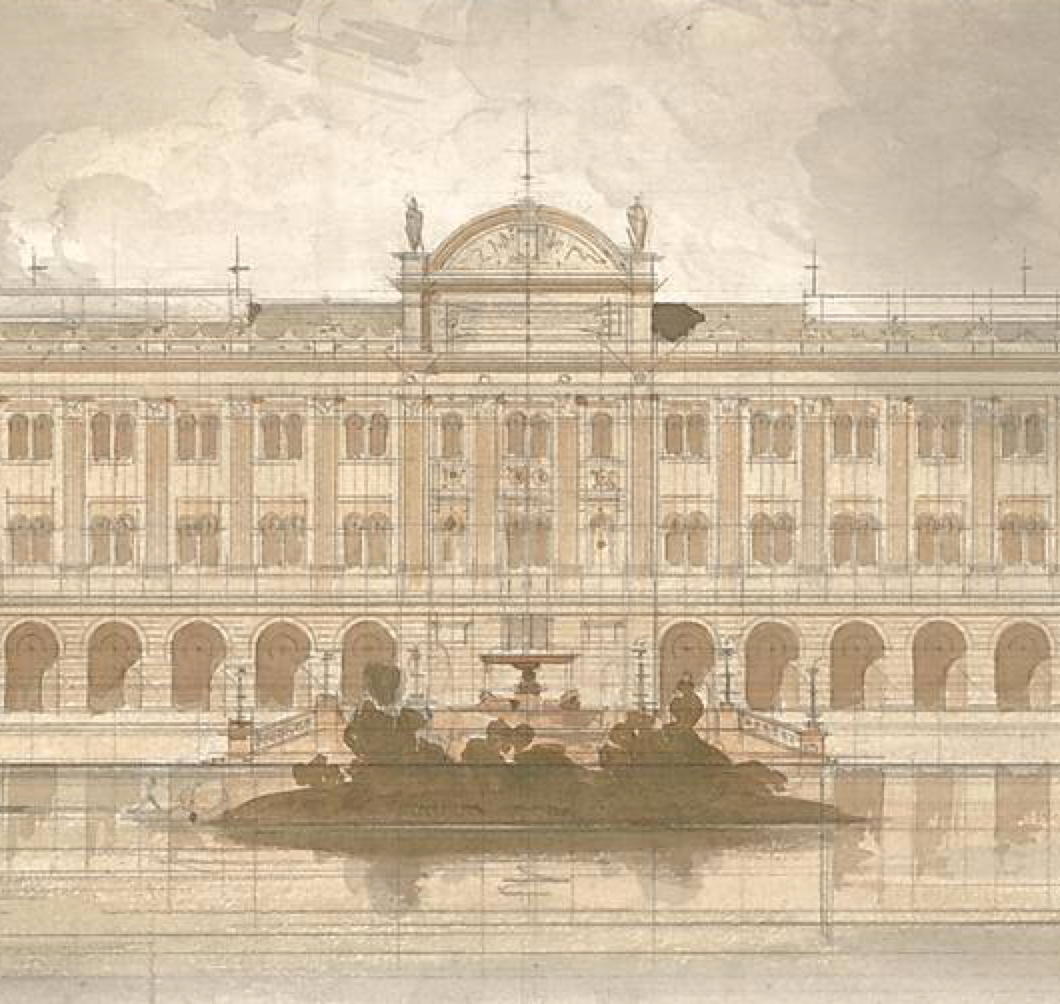

A Palace for the States-General

A Palace for the States-General

The nineteenth century was the great age for building parliaments. Westminster, Budapest, and Washington are the most memorable examples from this era, but numerous other examples great and small abound in Europe and beyond.

The States-General of the Netherlands missed out on this building trend, perhaps more surprisingly so given their cramped quarters in the Binnenhof palace of the Hague. The Senate was stuck in the plenary chamber of the States-Provincial of South Holland with whom it had to share, while the Tweede Kamer struggled with a cold, tight chamber with poor acoustics.

The liberal leader Johan Rudolph Thorbecke who pushed through the 1848 reforms to the Dutch constitution thought the newly empowered parliament deserved a building to match, and produced a design by Ludwig Lange of Bavaria. All the Binnenhof buildings on the Hofvijver side would be demolished and replaced by a great classical palace.

Despite members of parliament’s continual complaints about their working conditions, Thorbecke and Lange’s plans were vigorously and successfully opposed by conservatives. As the academic Diederik Smit has written,

A large part of the MPs was of the opinion that such an imposing and monumental palace did not fit well with the political situation in the Netherlands. […] In the case of housing the Dutch parliament, professionalism and modesty continued to be paramount, or so was the idea.

In fact, as Smit points out, significant alterations were made to the Binnenhof, like the demolition of the old Interior Ministry buildings by the Hofvijver, but these were replaced with structures that were actually quite historically convincing.

Further plans were drawn up in the 1920s — including a scheme by Berlage — but MPs felt that none of the proposals quite got things right and they were shelved accordingly. It wasn’t til the 1960s that the lack of space and the poor conditions in the lower chamber forced action. All the same, efficiency was the order of the day, as the speaker, Vondeling, made clear: “It is not the intention to create anything beautiful”.

Even then it wasn’t until the 1980s that the work was started, and the MPs moved into their new chamber in 1992. As you can see in this photograph, Vondeling’s aim of avoiding anything beautiful or showy has been achieved. The new chamber is certainly spacious — indeed some MPs claim it is too spacious. The art historian and D66 party leader Alexander Pechtold pointed out the distance between MPs inhibits real debate, unlike in the British House of Commons, and to that extent parliamentary design is inhibiting real democracy.

Arms and the Man

GOVERNOR CUOMO — is there anything that man won’t fiddle with? Is there nothing that can escape his grasping hands? Are we to suffer from the incessant interference of this megalomaniac forever?

The latest trespass His Excellency has committed is to encroach upon the very sacred symbols of the Empire State itself: our beloved coat of arms — and, by extension, the flag which also bears it aloft.

Gaze upon its beauty, for you will see it fade. Azure, in a landscape, the sun in fess, rising in splendour or, behind a range of three mountains, the middle one the highest; in base a ship and sloop under sail, passing and about to meet on a river.

This beautiful device was adopted by the very first Assembly and Senate of the State of New York back in 1778, having been designed a year earlier. It has remained substantially unchanged since the 1880s until Governor Cuomo in one of his fits of fancy decided to sneak a change via the state budget, of all things.

“In this term of turmoil, let New York state remind the nation of who we are,” Governor Cuomo said in his State of the State address in January of this year. “Let’s add ‘E pluribus unum’ to the seal of our state and proclaim at this time the simple truth that without unity, we are nothing.”

Why the national motto should be interjected into the state flag when we have our own motto is beyond me. Rather than introduce a bill that would allow an open debate on the matter, the Governor decided to sneak it into the state budget. This passed in April, so the coat of arms, great seal, and flag of the state of New York have all now been altered to include the superfluous words.

That said, I have a sneaking suspicion the change might be honoured more in the breach than in the observance. Flag companies doubtless have a large back supply of pre-Cuomo flags to shift and customers are rarely up to date on matters vexillological and heraldic. I suspect that the next time you float down Park Avenue and see the giant banners fluttering from corporate headquarters very few will have updated their state flag.

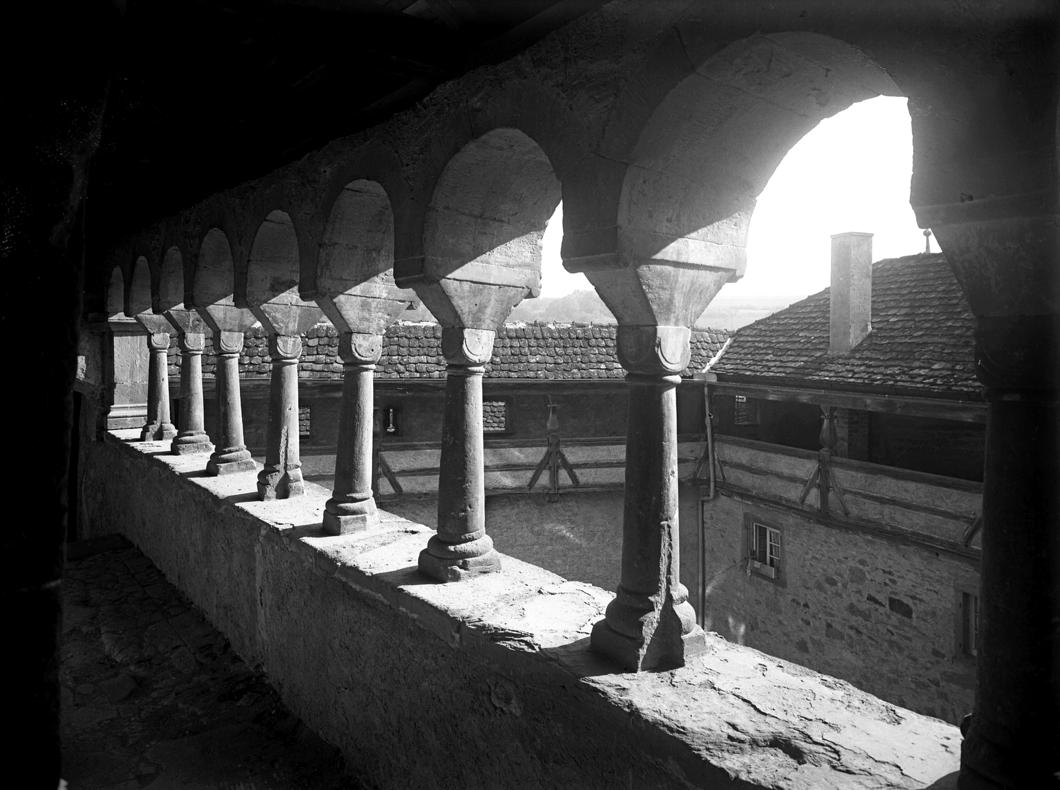

Großcomburg

While the old basilica was demolished in the 1700s and replaced with a baroque creation there is still plenty of Romanesque abiding at Großcomburg in Swabia. The monastery was founded in 1078 and the original three-aisled, double-choired church was consecrated a decade later. Its community experienced many ups and downs before the Protestant Duke of Württemberg, Frederick III, decided to suppress the abbey and secularise it. Many of its treasures were melted down and its library transferred to the ducal one in Stuttgart where its mediæval manuscripts remain today.

From 1817 until 1909 the abbey buildings were occupied by a corps of honourable invalids, a uniformed group of old and wounded soldiers who made their home at Comburg.

In 1926 one of the first progressive schools in Württemberg was established there, only to be closed in 1936. Under the National Socialists it went through a variety of uses: a building trades school, a Hitler Youth camp, a labour service depot, and prisoner of war camp.

With the war’s end it housed displaced persons and liberated forced-labourers until it became a state teacher training college in 1947, which it remains to this day.

Black-and-white photography is particular suitable for capturing the beauty and the mystery of the Romanesque.

These images of Großcomburg are by Helga Schmidt-Glaßner, who was responsible for many volumes of art and architectural photography in the decades after the war.

F.X. Velarde: Forgotten & Found

Many of the architects of the “other modern” in architecture were forgotten or at least neglected once the craft moved in a more avant-garde direction.

The British Expressionist architect F.X. Velarde who produced a number of Catholic churches in and around Liverpool in the interwar period and beyond is the subject of a new book from Dominic Wilkinson and Andrew Crompton.

There will be a free online lecture tomorrow on ‘The Churches of F. X. Velarde’ given by Mr Wilkinson, Principal Lecturer in Architecture Liverpool John Moores University. Further details are available here.

The book is available from Liverpool University Press with a 25% discount through the Twentieth Century Society. (more…)

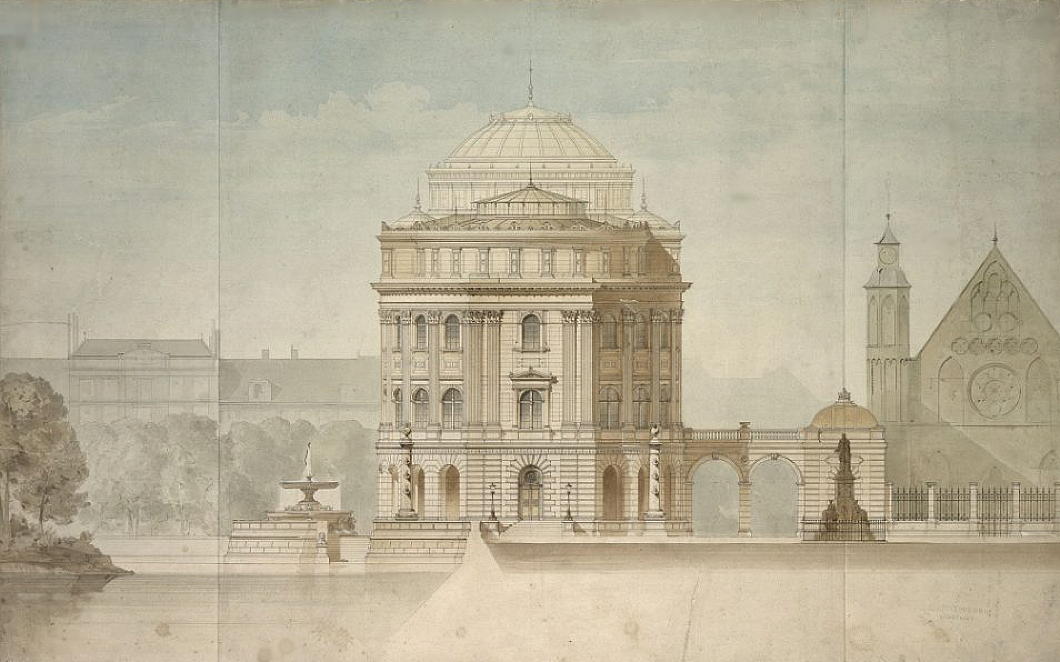

Romes that Never Were

When the splendidly named Saint Sturm – Sturmi to his friends, apparently – founded the Benedictine monastery of Fulda in A.D. 742 we can presume he had no idea that the magnificent church eventually erected there (above) would one day be considered for housing the Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church.

Rome, caput mundi, is ubiquitously acknowledged by all Christian folk as the divinely ordained location for the Papacy, but this has not always been acknowledged in practice. Most memorable is the “Babylonian Captivity” of the fourteenth century when the papal court was based at the enclave of Avignon surrounded by the Kingdom of Arles. The illustrious St Catherine of Siena was influential in bringing that to an end.

Since the return from Avignon the Successor of Peter has prudently been keen to stay in Rome, but various crises over the past two centuries have seen His Holiness shifted about. General Buonaparte successively imprisoned Pius VI and Pius VII while he made to refashion Europe in his likeness, and the later slow-boil conquest of the Italian peninsula by the Kingdom of Sardinia caused much worrying in the courts of the continents as well.

In 1870, the Eternal City fell to the troops of General Cadorna, and while the Vatican itself was not violated it was widely assumed the papacy could not stay in Rome. Pope Pius IX evaluated several options, one of them seeking refuge from – of all people – the Prussian king and soon-to-be German emperor Wilhelm I.

Bismarck, no ally of the Church, but shrewd as ever, was in favour of it:

I have no objection to it — Cologne or Fulda. It would be passing strange, but after all not so inexplicable, and it would be very useful to us to be recognised by Catholics as what we really are, that is to say, the sole power now existing that is capable of protecting the head of their Church. …

But the King [Wilhelm I] will not consent. He is terribly afraid. He thinks all Prussia would be perverted and he himself would be obliged to become a Catholic. I told him, however, that if the Pope begged for asylum he could not refuse it. He would have to grant it as ruler of ten million Catholic subjects who would desire to see the head of their Church protected. …

Rumours have already been circulated on various occasions to the effect that the Pope intends to leave Rome. According to the latest of these the Council, which was adjourned in the summer, will be reopened at another place, some persons mentioning Malta and others Trent.

Bismarck mused to Moritz Busch what a comedy it would be to see the Pope and Cardinals migrate to Fulda, but also reported the King did not share his sense of humour on the subject. The advantages to Prussia were plain: the ultramontanes within their territories and throughout the German states would be tamed and their own (Catholic) Centre party would have to come on to the government’s side.

In the end, of course, the Pope decided to stay put in Rome and became the “Prisoner of the Vatican”, surrounded by an awkward usurper state that made attempts at friendship without betraying its hopes for legitimising its theft of the Papal States. It was the diplomatic coup of the Lateran Treaty in 1929 that finally allowed both states to breathe easy and created the State of the City of the Vatican, an entity distinct from but subservient to the Holy See of Rome.

The Second World War brought its own threats to the Pope’s sovereignty, and the wise and cautious Pius XII feared he might be imprisoned by Hitler just as his predecessor and namesake had been by Buonaparte. Pius was determined the Germans would not get their hands on the Pope and so signed an instrument of abdication effective the moment the Germans took him captive. He would have burnt his white clothing to emphasise that he was no longer the Bishop of Rome.

The record is not yet firmly established but it is rumoured that the College of Cardinals was to be convened in neutral Éire to elect a successor. One wonders where they would have met. The Irish government would undoubtedly have put something at their disposal — Dublin Castle perhaps? Despite the whirlwind of war, the election of a pope in St Patrick’s Hall would have warmed the cockles of many Irish hearts.

But what then? Ireland’s neutrality would have been useful but a German violation of the Vatican’s territory would have been grounds for open, though obviously not military, conflict. Further rumours, also totally unsubstantiated, had it that the King of Canada, George VI, quietly had plans drawn up for offering the Citadelle of Quebec to the Pope to function as a Vatican-in-Exile. Others claim it wasn’t until the 1950s that Quebec was investigated as a possibility by the Vatican in case Italy went communist, as was conceivable.

So Cologne, Fulda, Malta, Trent? None of these plans ever occurred, thank God.

And what about England? Why not? The court of St James and the Holy See, despite obvious and significant differences, enjoyed close relations and overlapping interests in many particular circumstances from the Napoleonic wars until present. Pius IX had put feelers out to Queen Victoria’s minister in Rome, Lord Odo Russell, in 1870 but the British ambassador more or less told him of course the Pope would be welcomed in England but don’t be silly, the Sardinians would never conquer Rome.

One imagines the British sovereign would grant a palace of sufficient grandeur to the exiled Pontiff. Hampton Court would do the job. It’s far enough from the centre of London but large enough to house a small court and the emergency-time administration of the Holy Roman Church. Would the ghost of Cardinal Wolsey plague the Princes of the Church?

Thanks be to God, we’ve never had cause to find out. At Rome sits the See Peter founded and so it looks to remain. Ubi Petrus, ibi ecclesia.

Wardour

The news from the West Country is that Jasper Conran OBE is selling up his place in Wiltshire, the principal apartment at Wardour Castle.

Wardour is one of the finest country houses in Britain, designed by James Paine with additions by Quarenghi of St Petersburg fame. It was built by the Arundells, a Cornish family of Norman origin, but after the death of the 16th and last Lord Arundell of Wardour the building was leased out and in 1961 became the home of Cranborne Chase School.

A friend who had the privilege of being educated there confirms that Conran’s assertion of Cranborne Chase being “a school akin to St Trinian’s” was correct, and tells wonderful stories of the girls’ misbehaviour.

Alas the modern world does not long suffer the existence of such pockets of resistance, and the school shut in 1990. The whole place was sold for under a million to a developer who turned it into a series of apartments, for the most part rather sensitively done, if a bit minimalist.

The real gem of Wardour, however, is the magnificent Catholic chapel which is owned by a separate trust and has been kept open as a place of worship. Richard Talbot (Lord Talbot of Malahide) chairs the trust and takes a keen interest in the chapel and the building. I was down there the Sunday the chapel re-opened for public worship after the lockdown and Richard was there making sure all was well.

Those interested in helping preserve this chapel for future generations can join the Friends of Wardour Chapel.

Fête du Dominion

à tous nos amis canadiens!

Happy Dominion Day

to all our Canadian friends!

Canada is one of the most fascinating and interesting realms on the face of the earth, though the Canadians are a curiously humble people despite their immense achievements.

I’ve written some odd bits and bobs of Canadiana over the years, and thought a small selection of which might prove a suitable way of celebrating the great dominion’s national day.

CDU @ 75

Last week was the seventy-fifth anniversary of the foundation of Germany’s Christian Democratic Union, one of the most successful democratic political parties in postwar Europe.

Indeed, under Adenauer the CDU was one of the institutions which transformed relations between the peoples of Europe and started the process of integration which, alas, has not aged well.

Nonetheless, here are some election posters from the early years of the CDU — plus one from the 1980s. (more…)

Corpus Christi

It seems silly to let today’s feast pass without mentioning Corpus Christi College at the University of Oxford. It’s one of the smaller colleges, with about 250 undergraduates and a hundred or so postgraduates studying in its charming quadrangles.

Founded in 1517, Erasmus hailed its library as inter praecipua decora Britanniae, “among the chief ornaments of Britain”, and Cardinal Pole — the last legitimate Archbishop of Canterbury — was a founding fellow.

More recently, John Keble became an undergraduate there in 1806, before accepting a fellowship at Oriel in 1811, and having Keble College founded and named after him a few years after his death in 1866.

Architecturally, Corpus’s most remarkable feature is the Pelican Sundial, which is actually a column dating from 1579 that contains twenty-seven different sundials. It was most recently restored in 2016, and copies exist at Princeton and Pomfret.

The terrace atop the new auditorium affords an excellent view of the former priory of St Frideswide, now used by the Protestants as Christ Church. (more…)

Klein Gidding

Bekend nie, want nie gesoek nie

Maar gehoor, half gehoor, in die stilte

tussen twee golwe van die see.

Vinnig, nou, hier, nou, altyd –

’n Voorwaarde van volledige eenvoud

(Koste nie minder nie as alles)

En alles sal wel wees

Allerhande dinge sal wel wees

As die tonge van vlam inmekaar gevou is

In die gekroonde knoop van vuur

En die vuur en die roos is een.

Onze Grootste President

The London Residence of President Martin van Buren

Transacting some business in March before the plague struck us here in London I found myself with a moment to spare and made a brief pilgrimage to No. 7, Stratford Place. It was in this handsome townhouse that Martin van Buren, the first New Yorker to ascend to the chief magistracy of the American Republic, had his residence when he served as the United States’s minister to Great Britain in 1831.

While I often claim that Calvin Coolidge was America’s greatest president in reality my chief devotion in that contest is to the Little Magician himself, the Red Fox of Kinderhook.

Among the many characteristics of this esteemed Knickerbocker is that English was not his native language and throughout his career as a democratically elected politician he spoke with a thick Dutch accent. To his wife, he spoke almost entirely in Dutch.

Jay Cost and Luke Thompson’s Constitutionally Speaking podcast at National Review recently released the first of a two episodes about van Buren and while I’m no fan of podcasts in general this was worth listening to.

One of the factors Cost and Thompson highlight is the utility of the party machine structures of the day in solidifying the practice of America’s democracy and acting as a vehicle of accountability, something too little appreciated by most later observers of the period.

We keen Kinderhookers and Van Buren Boys await the second instalment with anticipation.

Shamefully I have not yet made the pilgrimage to Kinderhook itself, but it’s pleasing to learn that the dominie of the Dutch Reformed Church is a graduate of the greatest university in the southern hemisphere.

How Our Ancestors Built

The Hudson River Day Line Building in Albany

The visitor arriving at Albany, the capital of the Empire State, might be forgiven for presuming the riparian French gothic mock-chateau he first views is the most important building in town.

Built as the headquarters of the Delaware & Hudson, a canal company founded in 1823 that successfully transitioned into the railways, the chateau now houses the administration of the State University of New York. (Indeed, the Chancellor once had a suitably grandiose apartment in the southern tower.) That building, with its pinnacle topped by Halve Maen weathervane, is worthy of examination in its own right.

But next to this towering edifice is an altogether smaller charming little holdout: the ticket office of the Hudson River Day Line.

In the nineteenth century the Hudson River Valley was often known as “America’s Rhineland” and travel up and down the river was not just for business but also for the aesthetic-spiritual searching that inspired the Hudson River School of painters.

The Day Line’s origins date to 1826 when its founder Abraham van Santvoord began work as an agent for the New York Steam Navigation Company. Van Santvoord’s company merged with others under his son Alfred’s guidance in 1879 to form the Day Line. (more…)

The greatest church architect you’ve never heard of

The greatest church architect

you’ve never heard of

Ludwig Becker and His Churches

For such a prolific church architect of such high quality, not much is known about Ludwig Becker and, alas, he seems to be little studied. Born the son of the master craftsman and inspector of Cologne Cathedral, Becker had church building in his blood. He studied at the Technische Hochschule in Aachen from 1873 and trained as a stone mason as well.

In 1884 Becker moved to Mainz where he became a church architect and in 1909 he was appointed the head of works at Mainz Cathedral, a position he held until his death in 1940. His son Hugo followed him into the profession of church architecture.

That’s about all I can find out about Becker. But here are a selection of some of his churches, to get a sense of his agility in a wide variety of styles.

St Joseph, Speyer, is my favourite of Becker’s churches for the beautiful organic fluidity of its style. Here Art Nouveau, Gothic, and Baroque are mixed somehow without affectation. Rather enjoyably, it was built as a riposte to a nearby monumental Protestant church commemorating the Protestant Revolt. These two rival churches are the largest in the city after its famous cathedral. (more…)

‘Disgraceful Scenes at Stellenbosch’

The 1957 Intervarsity Match

Flicking through the argiewe the other day I stumbled upon this little report from Johannesburg’s Sunday Express of 26 May 1957 describing the displays of disrepute at the annual Intervarsity match, when the University of Cape Town takes on Stellenbosch.

AT STELLENBOSCH

annual rugger booze up

At Stellenbosch many students made the intervarsity match the occasion for a grand drinking spree. A number of them became drunk and disorderly; and here are some of the results of their liquor intake:

- A Cape Town student was hit on the head with a bottle, and was taken to hospital to have a gaping wound stitched.

- Another student was escorted from the pavilion by the police.

- A constable was hit by a bottle, thrown by a student.

- Flying bottles narrowly missed a number of other policemen.

- Although no damage was done, cardboard darts were thrown in the direction of the Prime Minister, to the accompaniment of insulting jeers.

- The pennant on a Cabinet Minister’s car was stolen.

- The chauffeur of the Governor-General’s car hid his pennant (which cost £7.10.0) in case it too disappeared.

- One Cape Town student was found lying drunk among the coloured spectators.

According to a police official, many drunk students armed with bottles of liquor, turned up for the match. So bad was it that he eventually told the gate keepers not to allow them in. A policeman was obliged to stand guard over Ministerial cars.

I’m pleased to say the Sunday Express revealed that “the worst offenders were the Cape Town students”, not the Maties. “Bottles of whisky, vodka, wine and champagne were much in evidence on [the UCT] stands.”

depicting die ridder van Matieland having easily defeated the Ikey dragon.

Buchan in Quebec

While the Salon bleu in Quebec’s parliament used to be green, the Salon rouge has kept its lordly colour. Conservative Quebec was the last of the Canadian provinces to abolish its unelected upper house which faced the chop in 1968, that year so beloved of duty-shirkers and ne’er-do-wells.

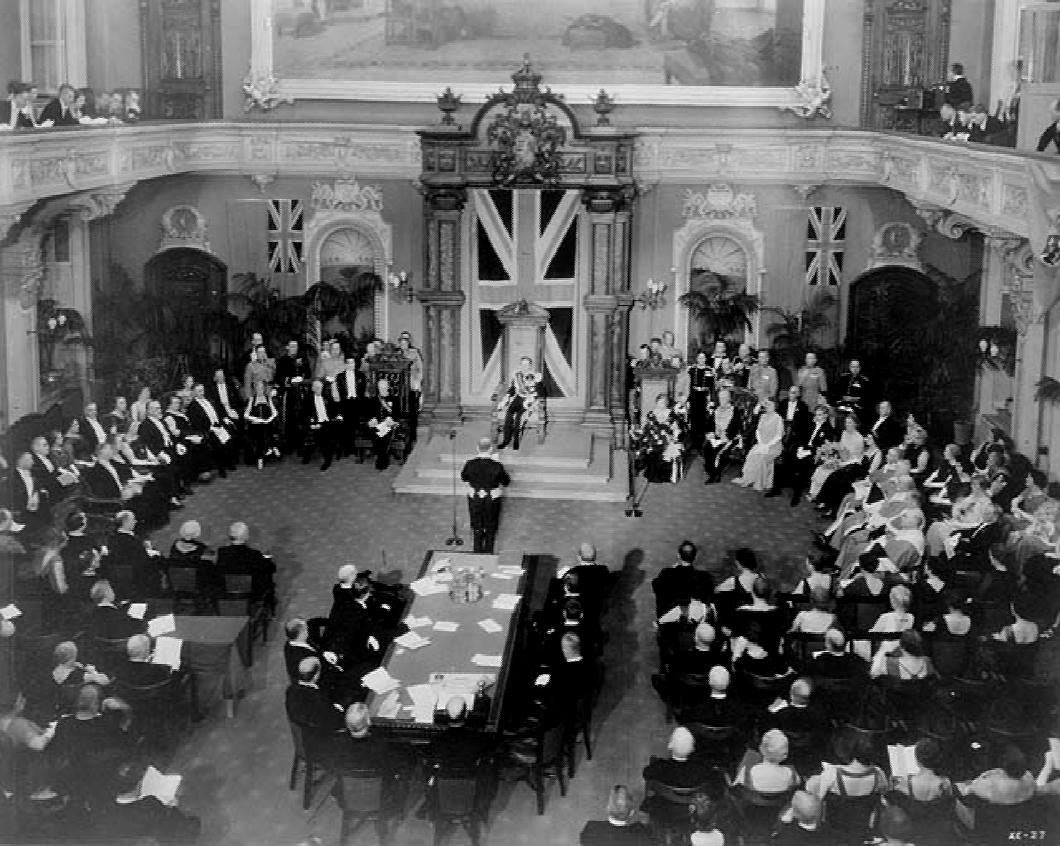

Thirty-three years earlier, the Salon rouge was the scene of a more regal ceremony: the official installation of the Scots writer and statesman John Buchan as Governor General of Canada. Being a Presbyterian with an in-built (but in his case only occasional) tendency to dourness, Buchan wanted to go as an ordinary commoner but the King of Canada insisted on a peerage for his viceregal representative in the dominion.

Thus it was Lord Tweedsmuir who arrived in Quebec in 1935 and was installed as Governor General in the Salon rouge on All Souls’ Day of that year. Above, the Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King gives an address after the swearing-in.

Buchan proved an influential Governor General and helped set the tone of Canada’s monarchy in the aftermath of the 1931 Statue of Westminster that recognised the distinct nature of the Commonwealth realms. He also orchestrated the King’s successful 1939 trip across Canada — which also featured the King and Queen holding court in the Salon rouge of Quebec’s Parliament.

By the time of his death in post in 1940, John Buchan had become His Excellency The Right Honourable The Lord Tweedsmuir GCMG GCVO CH PC. Not a bad end to a good innings.

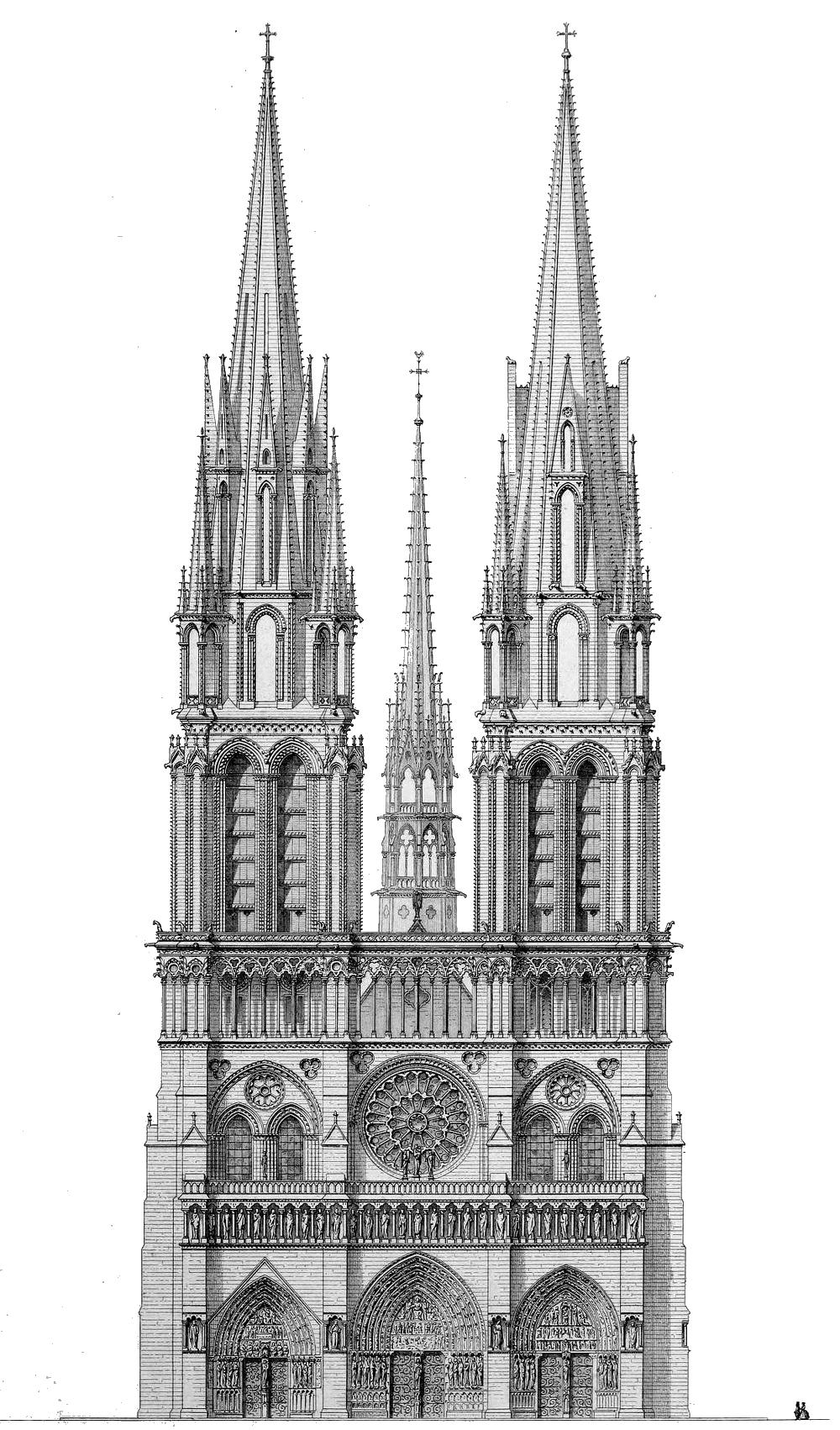

Notre-Dame de Paris

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

1844

Doom in Bloom

Such paintings were widespread in Catholic England where they served as a vital reminder to the faithful worshipping below of not just the torments of Hell but also the joys of Heaven. In the aftermath of the Protestant revolt, however, such vivid imagery was frowned upon, and the Salisbury Doom was painted over with limewash in 1593. Christ in Majesty was replaced by the royal arms of the usurper queen, Elizabeth I.

It was then forgotten about til its rediscovery in 1819 when hints of colour were discovered behind the royal arms. The limewash was removed, the remnants of the painting were revealed, recorded by a local artist, and then covered over yet again in white. Finally in 1881 the Doom was revealed to the world and subject to a Victorian attempt at restoration with mixed results.

Work on the church’s ceiling in the 1990s allowed experts to better examine the Doom which determined that, while there was a bit of fading, dirt was hanging loosely to the painting and it would be ripe for restoration. It has only been more recently, however, that money has been raised to restore the Doom.

There are other glories in this church yet to be restored, about which more information can be found on the parish’s website.

The Salisbury Doom before restoration (above) and after (below).

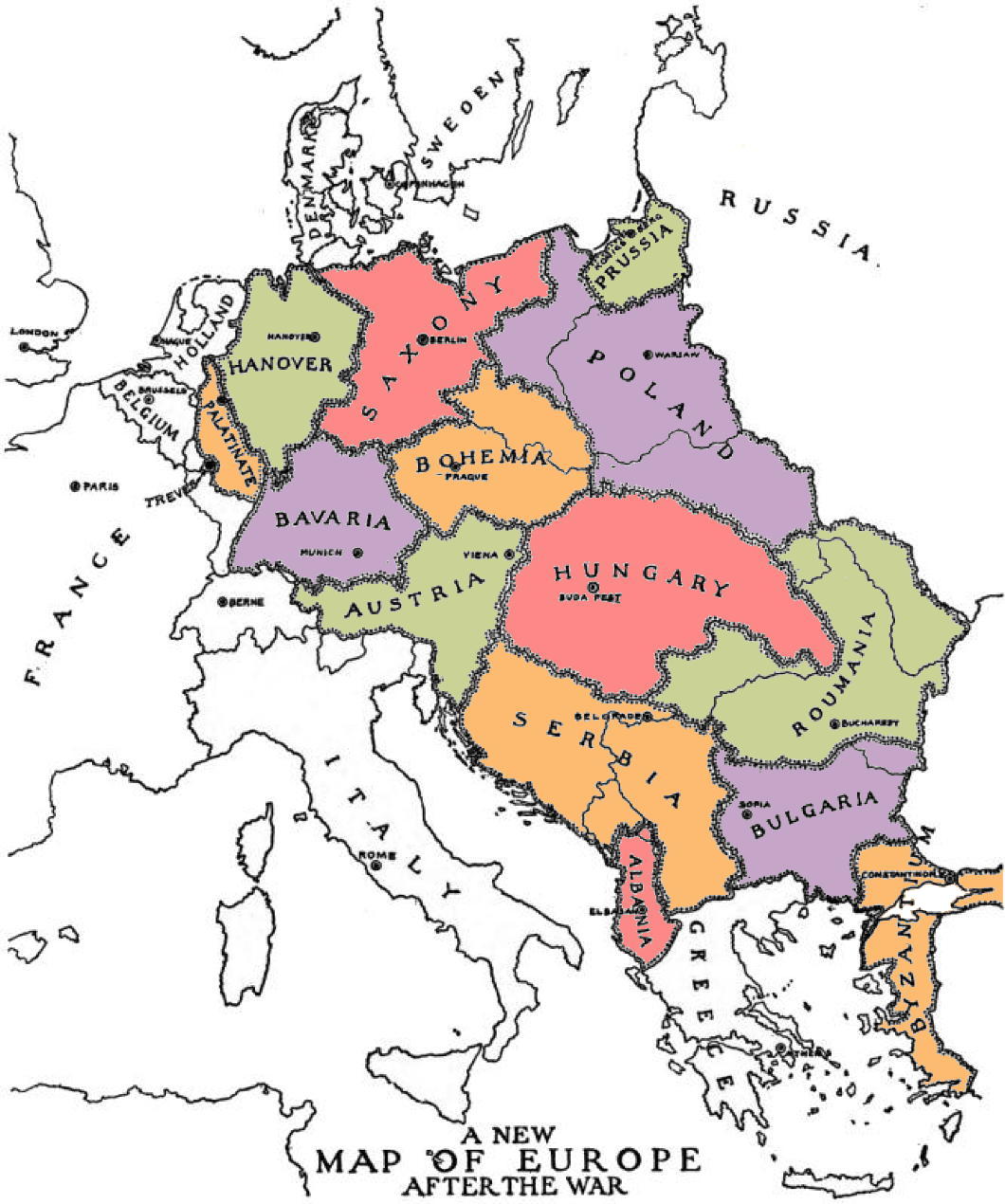

‘Solving’ Middle Europe

Ralph Adams Cram’s First-World-War Plan for Redrawing Borders

Ralph Adams Cram was not just one of the most influential American architects of the first half of the twentieth century: he was a rounded intellectual who expressed his thinking in fiction, essays, and books in addition to the buildings he designed.

Cram (and arguably even more his business partner Goodhue) had a gift for bringing the medieval to life in a way that was neither archaic nor anachronistic but instead conveyed the gothic (and other styles) as living, organic traditions into which it was perfectly legitimate for moderns to dwell, dabble, and imbibe.

His literary efforts include strange works of fiction admired by Lovecraft and political writings inviting America to become a monarchy. These have value, but it’s entirely justifiable that Cram is best known for his architectural contributions.

All the same, amidst the clamours of the First World War this architect of buildings played the architect of peoples and sketched out his idea of what Europe after the war — presuming the defeat of the Central Powers — would look like.

In A Plan for the Settlement of Middle Europe: Partition Without Annexation, Cram set out his model for the territorial redivision of central and eastern Europe “to anticipate an ending consonant with righteousness, and to consider what must be done… forever to prevent this sort of thing happening again”.

Cram, who provided a map as a general guide, predicted the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France, Schleswig-Holstein to Denmark, the Trentino and Trieste to Italy, much of Transylvania to Romania, Posen to a restored Poland, and Silesia divided in three.

Fundamental to the architect’s thinking was that “neither Germany, Austria-Hungary, nor Turkey can be permitted to exist as integral or even potential empires”. Austria and Hungary would be split and Germany needed to be partitioned (not, as some later plans had it, annexed). (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories