World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Theodore Roosevelt

The ancient heresy of iconoclasm claimed a new victim this week: The statue of Theodore Roosevelt which graced the Manhattan memorial dedicated to him at the American Museum of Natural History has been removed at a cost of two million dollars.

The sculpture had attracted the ire of protestors who objected to the inclusion of a Native American and an African by the side of twenty-sixth President of the United States and sometime Governor of New York, which they claimed glorified colonialism and racism.

While the American Museum of Natural History is a private institution, it sits on land owned by the City, and the statue was paid for by the State.

The statue was doomed in June of last year when the New York City Public Design Commission voted unanimously to rip Teddy down.

As the New York Post put it, “He’s going on a rough ride!”

The statue was severed in two this week, with the top half removed and the bottom half following shortly after.

It will be shipped to the Badlands of North Dakota to be displayed as an object in a museum under construction there. (more…)

Problems and Solutions

There are in some periods problems to which no solutions exist.”

The St George’s Crucifix

A little bit goes a long way at Southwark’s Catholic cathedral

One of the privileges of living in St George’s Fields on the western marches of Southwark is the presence of St George’s Cathedral: the Catholic mother church for London south of the Thames, and indeed all the way out to Kent and the English Channel.

London’s two cathedrals match one another well. Both serve congregations that are incredibly diverse. At Westminster you are just as likely to find a peer of the realm as a Filipino cleaner. St George’s has an earthier mix, much populated by pious Africans of great dignity, young people, old people, and all the odd bits and bobs who give this part of London its welcoming character.

St George’s is a beautiful cathedral as well. Not without its flaws: the tower is unbuilt, the flooring is too bright and too cheap, and the sanctuary needs some ordering. But never let the perfect be the enemy of the good. The Cathedral took a direct hit from a German firebomb during the war, and — despite the immense loss of most of the Pugin ornamentation and decoration — architect Romilly Craze’s postwar re-building was an immense improvement on Pugin’s original design which that great architect had never really been satisfied with.

A reordering of the sanctuary as late as 1989 very much reflected the ideas of a decade or two earlier. The altar was brought forward into the nave, with the bishop’s throne the focus of attention and the choir shoved behind it. To avoid the visual distraction of the choirmaster, an metal installation with textile hangings stood behind the throne (colloquially known as “the towel rack”).

Luckily the crucifix and “big six” candlesticks from the 1958 re-consecration were found hidden away. Last month they were restored atop a short retable behind the cathedra and this small change has helped immensely in providing a more prayerful atmosphere and a stronger visual focus to the cathedral.

The photos above and below are from the Cathedral’s Advent Carol Service.

The contrast between before (above) and after (below) is subtle but effective.

The Saints are Glad

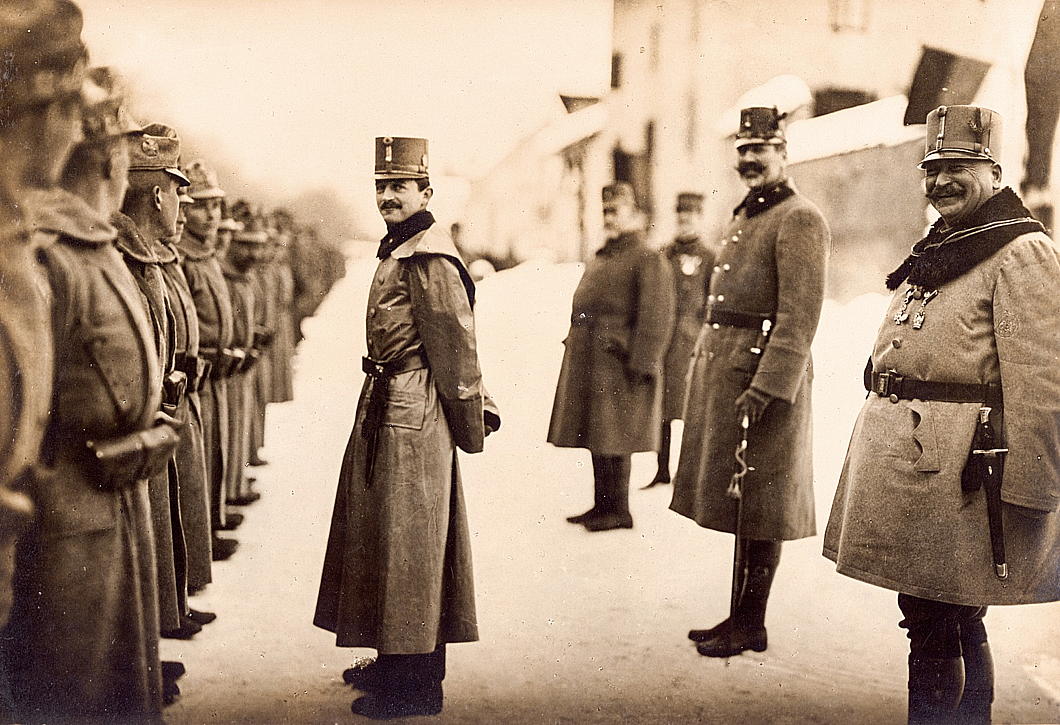

I love this photo of Blessed Charles — here still the heir to the throne — inspecting Austro-Hungarian troops in the Südtirol in 1916.

On the far right of the photograph, Gen. Franz (Ferenc) Rohr von Denta, commander of the Royal Hungarian Army, beams with a massive grin. He looks like a bit of a character.

Next to him is Archduke Eugen, the last Hapsburg to serve as Hoch- und Deutschmeister of the Teutonic Order, which in 1929 was transformed into a priestly religious order.

Franz Joseph would die just months after this photograph was taken.

His grand-nephew and successor Charles would be the last Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary, and King of Bohemia — amongst the myriad other titles — to reign (so far).

Abbott’s Gun

Berenice Abbott took a few photographs of New York’s old Police Headquarters viewed from one of the gunsmiths across Centre Market Place.

This street behind the NYPD HQ (which fronts on to Centre Street) became the gunsmiths’ district of Manhattan — policemen being one of the best customers for many of these businesses. (Criminals being another.)

There is something almost mediæval about the giant gun hanging outside, advertising to one and all what the shop had to offer.

Frank Lava, the gunsmith photographed, shut decades ago, but the John Jovino Gun Shop was originally next door before moving around the corner into Grand Street.

Like Lava’s, Jovino’s continued the tradition of hanging a giant gun outside the shop like in Abbott’s photograph.

The John Jovino Gun Shop, founded 1911, chucked in the towel last year when “Gun King Charlie” — owner Charlie Yu — decided the rent was too damn high.

An Interview with Philippe de Gaulle

Last year, in advance of the Admiral’s ninety-ninth birthday and the fiftieth anniversary of his father’s death, Paris Match sent Caroline Pigozzi to interview Philippe de Gaulle.

What follows is an abridged and completely unofficial translation of what Admiral de Gaulle insists will be his “last interview”.

ADMIRAL PHILIPPE DE GAULLE: Everyone has appropriated their share, even the Communists. All those who refer to General de Gaulle’s policy respect his Constitution, that of the Fifth Republic…

But, over the elections, my father’s imprint has faded. Pompidou, he was not quite his ideas anymore. Giscard d´Estaing, even less so… Mitterrand, basically, had the ideas of General de Gaulle, but he could not say it.

How do you judge the current president?

Emmanuel Macron is quite right to reference himself to the General as well as to other heads of state — France comes from the depths of the ages and the centuries call for it.

However, he is too involved in parliamentary life: the president should have a little more perspective. But anyway, it’s a Gaullist talking to you! The head of state is above Parliament and the government he appointed. It’s up to them to discuss day-to-day business. He has a prime minister who has to fight every day with his ministers and with Parliament.

And it’s up to the president, of course, to give direction, to choose. It is his “job”, just like dealing with the health crisis, which cannot stand any delay.

Which annual ceremonies have marked you the most?

The parade of 14 July, a commemoration of real scale which bears witness to the victories of the Republic.

My father would have liked to have celebrated on November 1 and 2 [All Saints’ and All Souls’ days] the remembrance of all war dead, for families, but that there were no other commemorations.

Why continue indefinitely with November 11, which marks the armistice of 1918, and May 8, the victory of 1945? Leave the public holidays to which the French are so attached, and let the state stick to these two dates.

Did your father like sports?

It was very important for him, because it marked the vitality of France. In his eyes, a country that had no athletes was a country half-dead.

Did he read the press?

He watched the news every night — it interested him to see what the French saw.

And, of course, he read Paris Match every week. I’m not saying that to flatter you: your newspaper is the only one that reported on La Boisserie during his lifetime.

He also read the dailies, even [the Communist] L’Humanité, but not always Le Monde, which he called for a time L’Immonde [“the foul”].

Do you know that it was de Gaulle who founded it? We do not mention it, but it’s the truth! Just after the war, in his office in rue Saint-Dominique, he asked Pierre-Henri Teitgen, Minister of State for Information, to find a journalist with a resistance background and recognised competence. The name Hubert Beuve-Méry was put forward.

My father summoned him: “You are going to make a newspaper like Le Temps before the war, which is politically neutral and with columnists. I’ll give you the money and the paper.

The first issue didn’t mention the General; in the second they started writing against him. In fact, Beuve-Méry never stopped running a pro-Fourth Republic daily, criticizing de Gaulle…

In another style, later on, my father discovered “Tintin” and “Asterix” thanks to my children, immersed in these readings during their vacations in Colombey.

Why was your mother known colloquially as “Aunt Yvonne”?

It was a nickname, as it sounded like Becassine. The truth is, people initially thought she was clumsy or frumpy. She wore her hair in a bun then, never interfering in anything.

She would go to see nuns for her charitable work, but on condition that no reporter showed up. Otherwise, she would turn right around.

You have never heard my mother speak of her charitable work, although she was devoted to it all her life! Sometimes I went with her. One day, with her, with nuns caring for hearing-impaired boys aged 4-5, the sisters played the piano for them and they put their little heads close to the keyboard. Poor people!

My mother had a knack for tackling little-known causes. She ended her life in the retirement home of the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception in Paris. There she was sure the nuns would neither speak to nor receive journalists.

Did the General use the familiar form “tu” easily?

He said “vous” to women, “tu” was more often used for regimental comrades. But he never used the familiar with men, out of a sense of honour. Not even the Companions of the Liberation! How could he have said “tu” to a soldier? People who fight, risk their lives, deserve a certain dignity. Even if they are not worthy elsewhere…

My father vouvoyer-ed my two sisters, used “tu” with my sons, but not his granddaughter. My sister and I vouvoyer-ed our mother, and she tutoyer-ed all of us.

As for my father with his wife, sometimes he was formal, sometimes he was familiar — but in public it was generally “vous”. Me, he was familiar with me and I used “tu” with him.

Your father should have made you a Companion of the Liberation.

He hesitated and said to me, “After all, you were my first companion.”

I replied: “Not the first, the second after your aide-de-camp, Geoffroy de Courcel.”

“Yes, but I cannot name you companion, because then I would have to name three times as many and I cannot do it. Everyone will know that you were one of my first companions.”

(The admiral, his voice charged with emotion, will say no more.)

The last companion of the Liberation will be buried in the crypt of Mont Valérien.

This is the rule they drew up, and the General endorsed it. They settled it a bit like the Marshals of the Empire — when the Companions were united with their first chancellor, Admiral Georges Thierry d’Argenlieu, a monk-soldier who then returned to the Carmel under the name of Father Louis de la Trinité.

After the war, they chose to commemorate the Appeal, every June 18, outside the official state — that is to say not at the Arc de Triomphe but at Mont Valérien, where more than a thousand hostages and resistance fighters had been shot. They erected a wall and a crypt, the Fighting France Memorial, and decided that the last of them would rest there.

Of the 1,038 who received the Order of Liberation, including 271 posthumously, they are now only three: Pierre Simonet, 99 years old, formerly a soldier, Daniel Cordier, centenarian, former secretary of Jean Moulin then merchant of art, and Hubert Germain, the dean of the order, also a hundred years old, who was deputy then minister under Georges Pompidou. He was supposed to join the navy with me and I found him on the “Courbet”, but he ultimately didn’t want to be a sailor anymore.

My father created the order on 16 November 1940 to reward individuals, civilian and military units, and civilian communities working to liberate France. He maintained a special bond with his Companions from all walks of life and from all political parties, even the Communist Party…

[Hubert Germain, the last Companion, died earlier this year and was buried at Mont Valérien after being recognised with full honours at Les Invalides.]

Father Euvé, the Jesuit who heads the prestigious review Etudes, explains that the Society of Jesus educates people for great destinies.

No less than two presidents under the Fifth Republic: de Gaulle and Macron!

It is clear that the Jesuits teach the meaning of the state and how to present oneself. Emmanuel Macron, a former student of La Providence in Amiens, a Jesuit institution, indeed has this talent.

Certainly he should speak a little more briefly, but he presents himself well and he is young. For me, he has not exhausted his full potential… And if he goes, who will be there? Tell me! I don’t see anyone else at the moment.

But back to the Jesuits, where my father studied. As a kid, I was in Saint-Joseph in Beirut, but it was the nuns who took care of us. Charles de Gaulle, on the other hand, attended the College of the Immaculate Conception, rue de Vaugirard, in Paris, which is now closed. His father taught there and was even its lay director after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1901.

What a training! You should know that when a seminarian enters the Jesuits, he begins his studies again for nine years. Jesuits have a taste for the state and a sense of power. They educate people for administration, science, exploration, astronomy… So it’s important first, I stress, to know how to present yourself. Thus, the theater, rich in lessons, helps in this.

Was the General’s piety one of their legacies?

For him, life did not exist without the Creator. He could not believe in a universe that emerged out of pure chance and found the Catholic religion to be the most human, the most balanced, the one that accompanied you best until the end, and that had given rise to the most sacrifices and dedication.

The General had a deep fervour throughout his existence, with great Christian roots, marked among others by the readings of Jacques Maritain and Charles Péguy, and also by the Jesuits. It corresponded to an intimate devotion, to an interiorisation of his faith, that of a being active in the world who did not keep his baptismal certificate in his pocket.

Doesn’t France have centuries of Christianity behind it? However, in the courtyard of the Elysée, laïcité oblige: there was no waltz of cassocks.

On the other hand, remember, in 1946 it was picturesque to see, for example, Canon Kir and Abbé Pierre sitting amidst the benches of the National Assembly.

Nevertheless, men of God must be concerned with the spiritual and, in a certain way, the social.

Admiral, tell us about your second professional life.

Indeed, from September 1986 to September 2004, I was in the Senate for the RPR and then elected a UMP city councillor in Paris.

Chirac had come to get me for the municipal elections. We campaigned all over the capital and, on March 6, 1983, he snatched eighteen out of twenty arrondissements!

It was until I was 84 — the age at which my maternal grandfather died, which at the time seemed very old to me — that I was a senator for Paris. Although the cliché of the senator dozing after meals is outdated, it was no longer the navy when I was constantly running around. An admiral is a fellow who moves from boat to boat, day and night.

How did you experience the lockdown?

I haven’t been out at all but, as I’ll be 99 soon, that doesn’t really matter! It was sometimes awkward to get to the bank or run an errand as I’m now a widower on my own.

I can’t walk anymore. Taking five steps one way and five the other, your knees are rusting. Many old people are dead, masked, “emblousinés”.

My children brought me fruit but it had to be put in a bag — it was all very compartmentalised.

And how is your daily life going now?

When everything is going well, I get visits from time to time from my family — my four sons gave me six grandchildren and two great grandchildren.

I read a lot of history books; I answer a lot of the mail that mostly comes from the descendants of Free French people. I listen to classical music, I watch the big games of tennis, rugby, football on television.

And also the James Bond films, films by Melville, Louis de Funès like ‘Le Petit Baigneur’, westerns, and documentaries on animals, nature with its distant landscapes, deserts, the Far North… There are magnificent places, countries where I have not been and where I will never go: Mongolia, the Himalayas… I only did mountaineering on screen. (He laughs.)

Was the cinema one of the General’s rare “distractions”?

He liked to see films, pre-war comedians and great actors such as Charles Boyer, Fernandel, Louis de Funès… He also liked Michèle Morgan, whom he found quite jolie, with a lot of allure, acting well.

At the Elysée Palace, having little time, he mainly watched the news. This had led to some myths, such as that of an announcer who was said to have been kicked out because my mother thought it was inappropriate for her to show her knees. Completely ridiculous! My mother did not get involved in this, especially since those in the audiovisual sector were more for de Gaulle, while the print media were often against him.

Has President Macron come to visit you, a few days before this historic anniversary?

Why would he do that? Be serious: he has no time to waste! He already sees far too many people and, at almost 99 years old, you are just a vestige of yourself.

[But on this, Admiral de Gaulle’s 100th birthday, President Macron has issued a communiqué.]

A vestige with the great pride of being called de Gaulle!

I admit I found it heavy, but hey, that’s how it is. We don’t choose such things. Carrying this name hindered my own freedom, constrained me to a lot of discretion. Besides, I joined the navy so as not to be in the army, where I would have had an impossible life. The navy is looking out to sea!

Lastly: write it down that this is my last interview. I insist! I am now too old for that. And don’t tell my sons that I gave you an interview. I’ll have to tell them that it was you who caught me, “caught” me. So, thank you for the photos, the historic Paris Matches and the cake. I shouldn’t eat cake anymore… At my age, sugar isn’t very good!

A Metropolitan Christmas

I suppose Whit Stillman’s ‘Metropolitan’ is not strictly speaking a Christmas film but Yuletide is as good a time as any to watch the most Upper-East-Side movie ever to make the silver screen.

It includes a scene (clip above) from the Service of Nine Lessons and Carols at St Thomas, Fifth Avenue, which to my mind is the best carol service in New York. It’s even better when followed by a few drinks at the University Club one block up.

Know Your Counties!

A very useful resource: the Wikishire map

While we all still live in the ruins left by the Tyrant Heath when he destroyed local government in this realm, it is always re-assuring to hear of those who perpetuate the old ways of eternal England. Heath created ‘administrative counties’ on top of the traditional counties, and these new counties ran riot over ancient boundaries.

For example, Abingdon, which is the county town of Berkshire, now finds itself confusingly administered by Oxfordshire County Council. Worse, many newly arrived emigrants from London and other parts know no better and refer to Abingdon as being ‘in’ Oxfordshire rather than merely being administered by it.

Berkshire’s beautiful baroque County Hall now sits empty and unused, frozen in formaldehyde and reduced to the status of a mere museum rather than a living, breathing thing.

Contrary to the belief of some, traditional counties have never been abolished and they are even perfectly valid for postal addresses. Many, when doing their annual round of Christmas cards, prefer to include the traditional county when addressing envelopes.

If you are unsure of what county your addressee lives in, there is now a very useful resource from a website called Wikishire: a Google map of all the traditional counties in the home nations — England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales.

Simply plug in the post code or town name and it will show you the proper county in which the spot in question is located. A happy marriage of new technology and the old, undying ways!

From Buda towards Pest

A 1959 view from the Vienna gate of Budapest’s Castle district

Taken in 1959, a photograph in the Fortepan archive shows two girls standing on the stone bench of the Vienna Gate — rebuilt in 1936 to mark the two-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of Buda’s liberation from the Ottomans.

Hungary’s domed neogothic Parliament Building sits in Pest on the opposite bank of the Danube in the distance, with the baroque spire of the Church of the Wounds of St Francis nearer on the Buda side of the river.

Sadly, this fine view can no longer be seen: the trees in the park below the Bastion promenade have been allowed to grow too tall. A somewhat superfluous flagpole bears the banner of Budapest’s 1st District.

The Hungarian government has invested a great deal of care and attention (not to mention investment) to the Castle quarter in recent years, so perhaps restoring this view could be added to their to-do list.

Gut Wulfshagen

I love when a house is arranged with its farm buildings around a garth or a gaard or a hof.

At Gut Wolfshagen in Schleswig-Holstein the barns are arranged flanking a narrow pinch that gives just a hint of the manor house beyond, lending an air of baroque surprise.

This house was built by Andreas Pauli von Liliencron at the very end of the seventeenth century and was acquired by the von Qualen family in 1787.

When the last of the von Qualens here died childless in 1903 they bequeathed Gut Wulfshagen to the uxorial nephew Ludwig Graf zu Reventlow. (more…)

How to deal with ‘Direct Action’

A lesson from the experienced generation of not so long ago

BRITONS have a habit of being slow to move initially but they do get their act in order sooner or later — and usually in time to prevent disaster. Many in the metrop. have been damned irritated that the police seemed impotent when the fascist death cult “Extinction Rebellion” first reared its ugly head.

“XR” prevented working-class Londoners from getting to work on the Underground and seized bridges to publicise their claim that — despite global agricultural yields being higher than ever before in human history — we are somehow all going to be starving in a few years’ time due to “climate catastrophe”.

Nonetheless, having returned from Guernsey this morning, I find the streets of London pleasantly filled with the flying squads of the Metropolitan Police. The boys in blue are moving about in rapid response units, ready to deploy immediately whenever and wherever the Extincto-Nazis rear their ugly heads, thus keeping the streets open to all comers (bar those with nefarious designs of un-civic disorder).

“XR” are not the first to threaten (nor to deliver) “direct action”, but I was heartened when a friend shared this splendid example of how to deal with irate students allegedly delivered by the Warden and Fellows of Wadham College, Oxford, in 1968:

Dear Gentlemen,

We note your threat to take what you call ‘direct action’ unless your demands are immediately met.

We feel it is only sporting to remind you that our governing body includes three experts in chemical warfare, two ex-commandos skilled with dynamite and torturing prisoners, four qualified marksmen in both small arms and rifles, two ex-artillerymen, one holder of the Victoria Cross, four karate experts and a chaplain.

The governing body has authorized me to tell you that we look forward with confidence to what you call a ‘confrontation,’ and I may say, with anticipation.

This was less than a quarter-century after the victory of the Second World War, so Wadham could call upon an experienced gang to fill the ranks of its fellowship in those days.

I suppose Maurice Bowra was Warden of Wadham at this time. While a renowned buggerer, he did manage to die with a knighthood, a CH, and the Pour le Mérite (civil class) — which is not a bad innings all things considered.

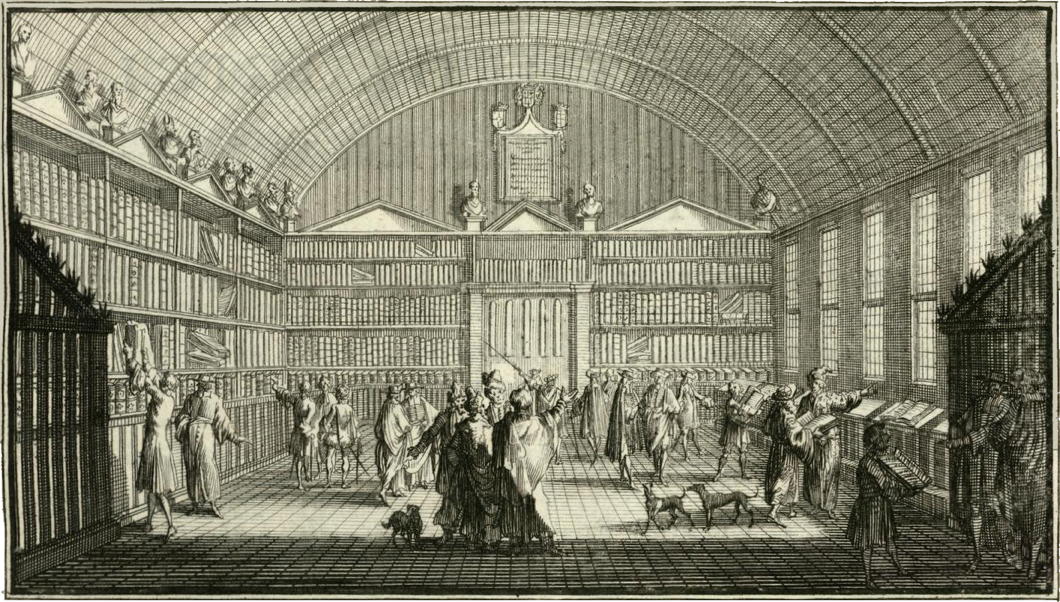

The University of the Frisians

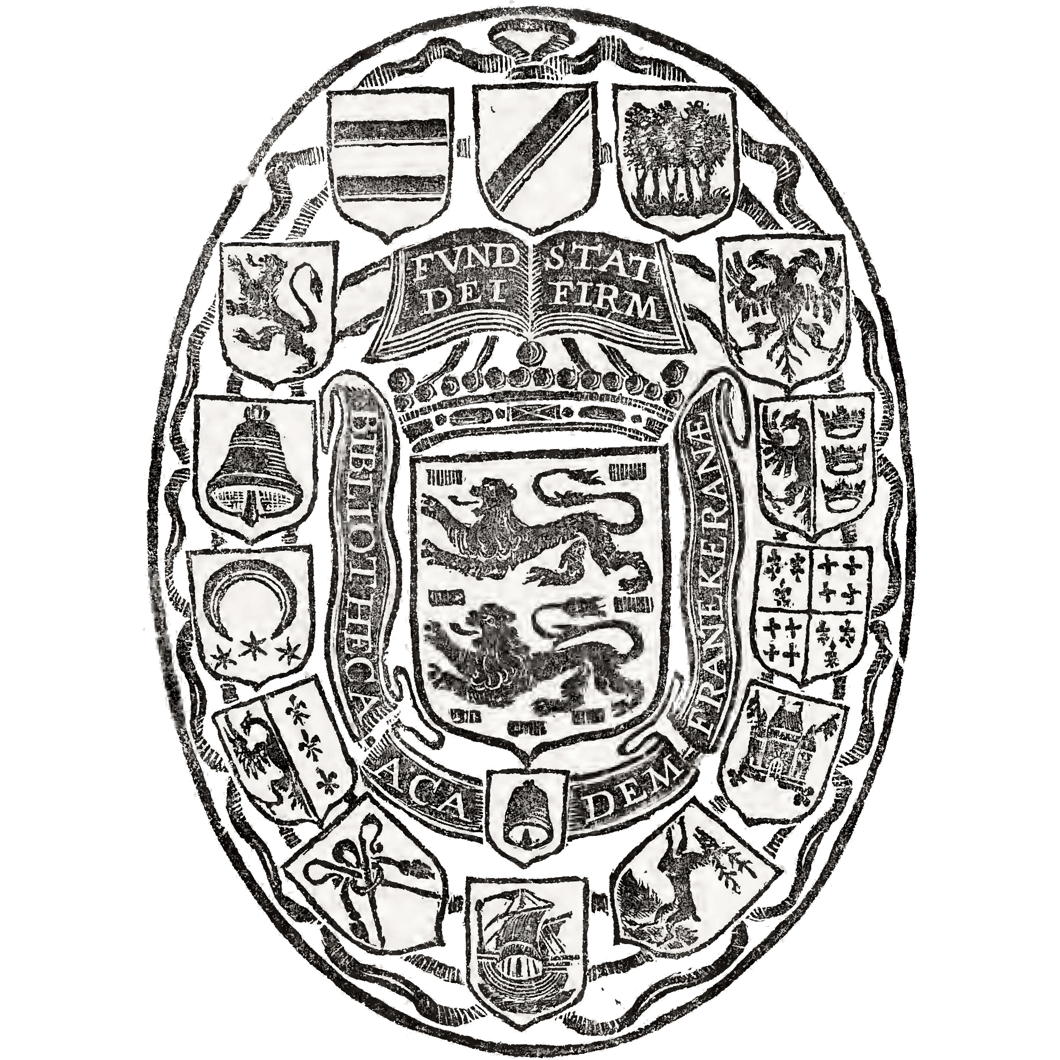

AMONG THE CURIOUS customs of the Netherlandish universities is a unique privilege whereby Frieslanders who are postgraduate students at the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen may defend their thesis in the Church of St Martin in Franeker. This privilege is also extended to those whose dissertations are on Frisian subjects or themes. The reason for this is that Franeker — one of the historic eleven cities of Friesland and today a town of 12,000 souls — formerly had a university of its own.

The University of Franeker (or Academy of Friesland) was established in 1585 by Willem Lodewijk of Nassau-Dillenburg, stadthouder of Friesland, as a Protestant foundation in the former cloister of the Canons Regular of the Order of the Holy Cross (sometimes called the Crosiers) whose confiscated property helped fund the new university.

As the only institution of higher learning in the northern part of the United Provinces, the University of Franeker met with some success in its early decades and its Protestant theological faculty earned particular reknown.

Its most famous student — so far as I am concerned — was a young Petrus Stuyvesant who studied philosophy and languages at Franeker in the 1610s before being sent to be governor of New Amsterdam. Unfortunately the revelation of an amorous relationship with his landlord’s daughter prevented young Stuyvesant from completing his studies.

From 1614 onwards, however, Franeker found a strong competitor when a university was founded in Groningen that was more successful at drawing in students from Germanic East Frisia. By the 1790s it had only eight students.

In 1811, when the Netherlands were directly annexed to the French Empire, Napoleon abolished the university entirely, alongside those of Utrecht and Harderwijk.

Its revival under the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815 met with little success as Franeker was denied the ability to grant doctorates and in 1843 even this academy was finally suppressed.

Incidentally, the fourteenth-century Martinikerk where Frisians can defend their theses today is also the only surviving medieval church in Friesland that has an ambulatory — and restoration work in the 1940s revealed twelve pre-Reformation frescoes of saints.

a Northumbrian of Frisian and New Yorkish origin

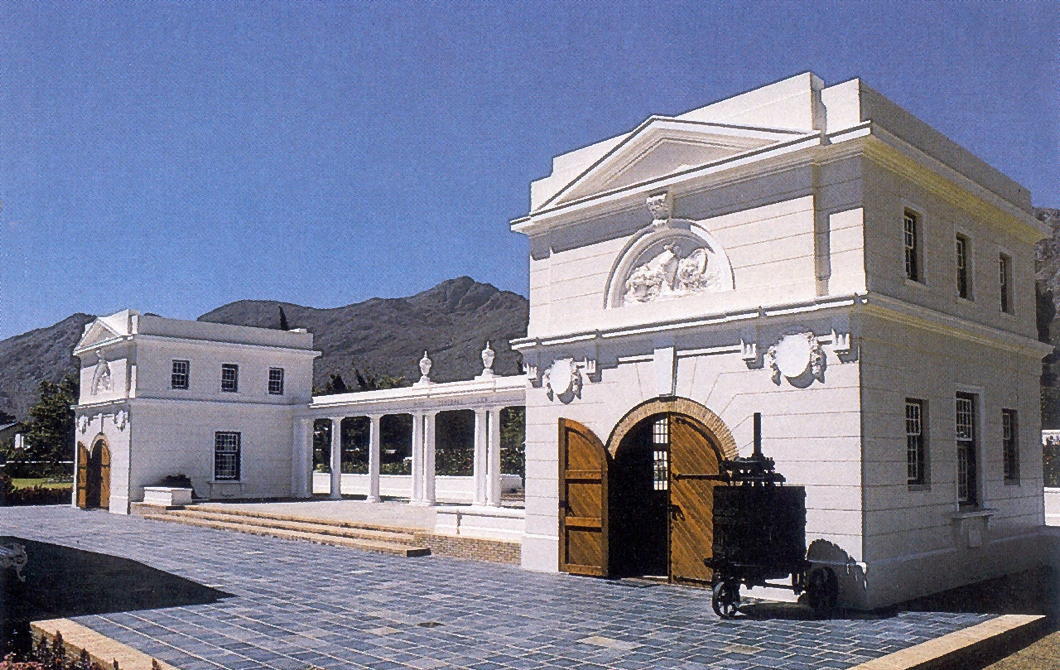

The old Dutch houses of the Cape

From Here There and Everywhere (1921) by Lord Frederic Hamilton:

THESE OLD DUTCH HOUSES are a constant puzzle to me. In most new countries the original white settlers content themselves with the most primitive kind of dwelling, for where there is so much work to be done the ornamental yields place to the necessary; but here, at the very extremity of the African continent, the Dutch pioneers created for themselves elaborate houses with admirable architectural details, houses recalling in some ways the chateaux of the Low Countries.

Where did they get the architects to design these buildings? Where did they find the trained craftsmen to execute the architects’ designs? Why did the settlers, struggling with the difficulties of an untamed wilderness, require such large and ornate dwellings? I have never heard any satisfactory answers to these questions.

Groot Constantia, originally the home of Simon Van der Stel, now the government wine-farm, and Morgenster, the home of Mrs. Van der Byl, would be beautiful buildings anywhere, but considering that they were both erected in the seventeenth century, in a land just emerging from barbarism seven thousand miles away from Europe, a land, too, where trained workmen must have been impossible to find, the very fact of their ever having come into existence at all leaves me in bewilderment.

These Colonial houses, most admirably adapted to a warm climate, correspond to nothing in Holland, or even in Java. They are nearly all built in the shape of an H, either standing upright or lying on its side, the connecting bar of the H being occupied by the dining-room. They all stand on stoeps or raised terraces; they are always one-storied and thatched, and owe much of their effect to their gables, their many-paned, teak-framed windows, and their solid teak outside shutters. Their white-washed, gabled fronts are ornamented with pilasters and decorative plaster-work, and these dignified, perfectly proportioned buildings seem in absolute harmony with their surroundings.

Still I cannot understand how they got erected, or why the original Dutch pioneers chose to house themselves in such lordly fashion. At Groot Constantia, which still retains its original furniture, the rooms are paved with black and white marble, and contain a wealth of great cabinets of the familiar Dutch type, of ebony mounted with silver, of stinkwood and brass, of oak and steel; one might be gazing at a Dutch interior by Jan Van de Meer, or by Peter de Hoogh, instead of at a room looking on to the Indian Ocean, and only eight miles distant from the Cape of Good Hope.

How did these elaborate works of art come there? The local legend is that they were copied by slave labour from imported Dutch models, but I cannot believe that untrained Hottentots can ever have developed the craftsmanship and skill necessary to produce these fine pieces of furniture.

I think it far more likely to be due to the influx of French Huguenot refugees in 1689, the Edict of Nantes having been revoked in 1685, the same year in which Simon Van der Stel began to build Groot Constantia. Wherever these French Huguenots settled they brought civilisation in their train, and proved a blessing to the country of their adoption. […]

Here, at the far-off Cape, the Huguenots settled in the valleys of the Drakenstein, of the Hottentot’s Holland, and at French Hoek; and they made the wilderness blossom, and transformed its barren spaces into smiling wheatfields and oak-shaded vineyards. They incidentally introduced the dialect of Dutch known as “The Taal,” for when the speaking of Dutch was made compulsory for them, they evolved a simplified form of the language more adapted to their French tongues.

I suspect, too, that the artistic impulse which produced the dignified Colonial houses, and built so beautiful a town as Stellenbosch (a name with most painful associations for many military officers whose memories go back twenty years ) must have come from the French.

Stellenbosch, with its two-hundred-year-old houses, their fronts rich with elaborate plaster scroll-work, all its streets shaded with avenues of giant oaks and watered by two clear streams, is such an inexplicable town to find in a new country, for it might have hundreds of years of tradition behind it!

Wherever they may have got it from, the artistic instinct of the old Cape Dutch is undeniable, for a hundred years after Van der Stel’s time they imported the French architect Thibault and the Dutch sculptor Anton Anreith. To Anreith is due the splendid sculptured pediment over the Constantia wine-house illustrating the stoiy of Ganymede, and all Thibault’s buildings have great distinction.

But still, being where they are, they are a perpetual surprise, for in a new country one does not expect such a high level of artistic achievement.

Bronxville’s Coat of Arms

The coat of arms of the Village of Bronxville is a surprisingly handsome design, for which we can thank a gentleman named Lt. Col. Harrison Wright.

The coat of arms of the Village of Bronxville is a surprisingly handsome design, for which we can thank a gentleman named Lt. Col. Harrison Wright.

Known to most as Hal, Wright (1887–1966) was one of those citizens who seemed to have had endless time to devote to those around them. In the Great War he served in a variety of roles and had the pleasure of personally delivering a Packard automobile to General Pershing.

He helped coordinate the village police when its captain’s ill health forced an unexpected retirement and was an active member of the American Legion post.

Wright was also Scoutmaster of Troop 1 and served as the local District Commissioner for the Boy Scouts. In that role he had under his purview a young scout from my old troop — Troop 2, Bronxville — named Jack Kennedy.

During the Second World War, Wright deployed his significant logistical expertise as an officer at the U.S. Army’s New York Port of Embarkation but, with his artistic skills and heraldic interest, he also found time in 1942 to design Bronxville’s coat of arms. (more…)

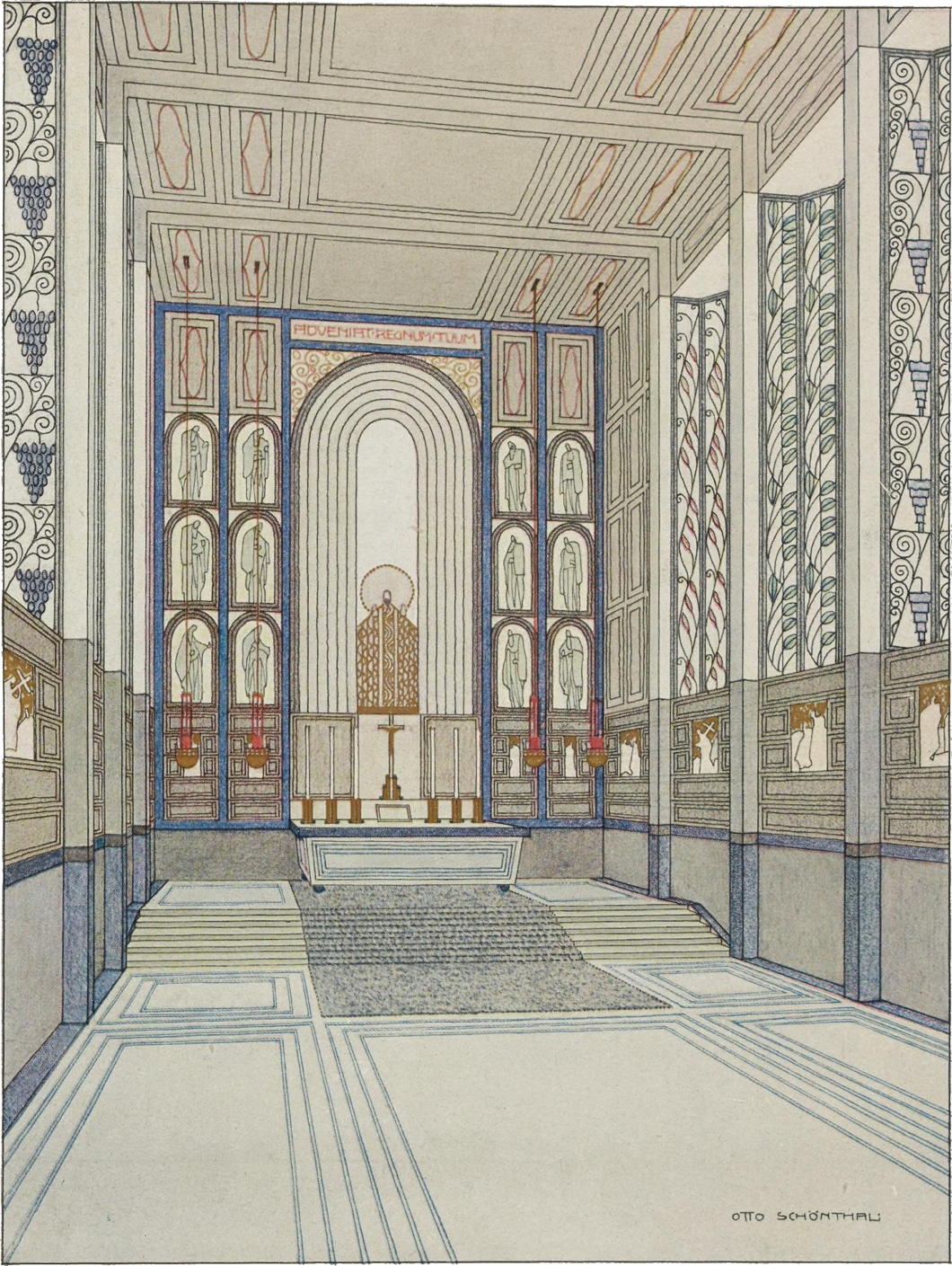

The Other Modern: Otto Schöntal

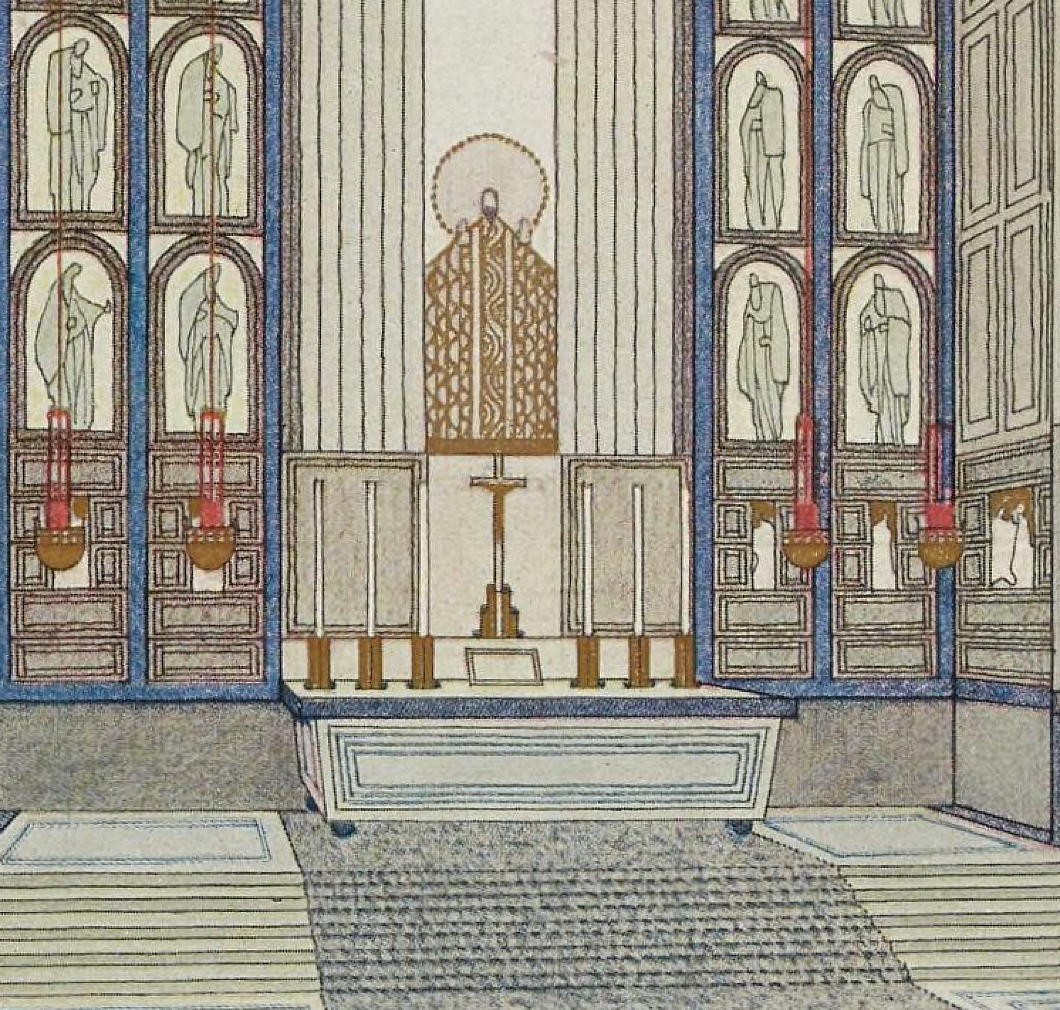

The Viennese architect Otto Schöntal was a student of Otto Wagner at the Academy of Fine Arts and exhibited this project for a Schloßkapelle in the periodical Moderne Bauformen in 1908.

It combines a simplicity of form with greater complexity in its decoration but like the work of many of the more mid-ranking architects of the Secession it comes across as a bit rigid and angular despite a certain freeness in its design.

An African View of the Heavens

Catholic Clerical Skygazers at the Cape of Good Hope

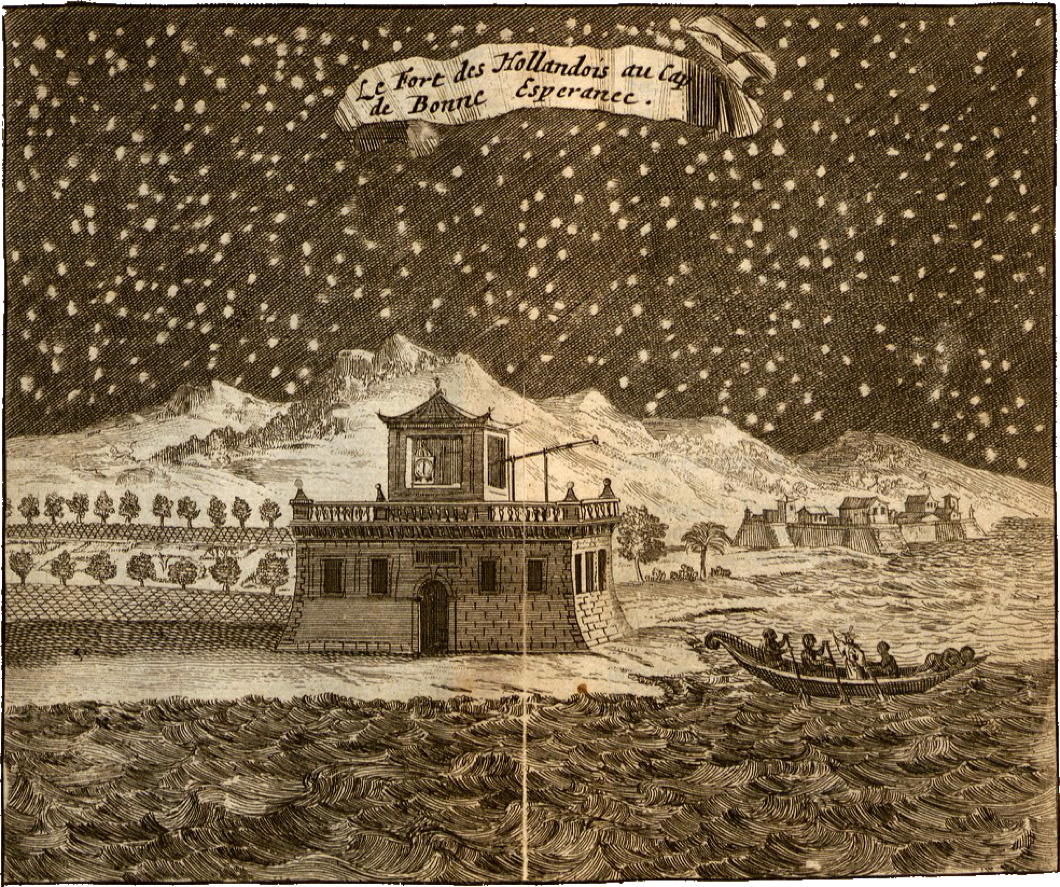

In 1685, the Jesuit mathematician, astronomer, and not-quite-secret-agent Fr Guy Tachard stopped off at the Cape of Good Hope en route to Siam as an emissary of the Sun King, Louis XIV.

Given Dutch hostility both to the French and to Catholicism, Père Tachard was surprised by the generous welcome provided by the governor, Simon van der Stel. Tachard was allowed to set up an astronomical observatory in the Company’s Gardens (today Cape Town’s equivalent of Central Park). No sooner had this happened than the clandestine Catholics of the colony searched the priests out.

“Those who could not express themselves otherwise knelt and kissed our hands,” one of the expedition’s priests wrote. “In the mornings and evenings they came privately to us. There were some of all countries and of all conditions: free, slaves, French, Germans, Portuguese, Spaniards, Flemings, and Indians.”

Those who spoke French, Latin, Spanish, or Portuguese were lucky enough to have their confessions heard but one thing was absolutely forbidden: the Mass. The Dutch authorities would not permit Mass to be offered on land, and local inhabitants were forbidden from visiting the French ships.

Once, while the priests took ashore a microscope covered in beautiful Spanish gilt leather, locals suspected them of trafficking in the Blessed Sacrament such that the clerics were forced to demonstrate the use of the microscope to prove they were heeding the Governor’s instructions.

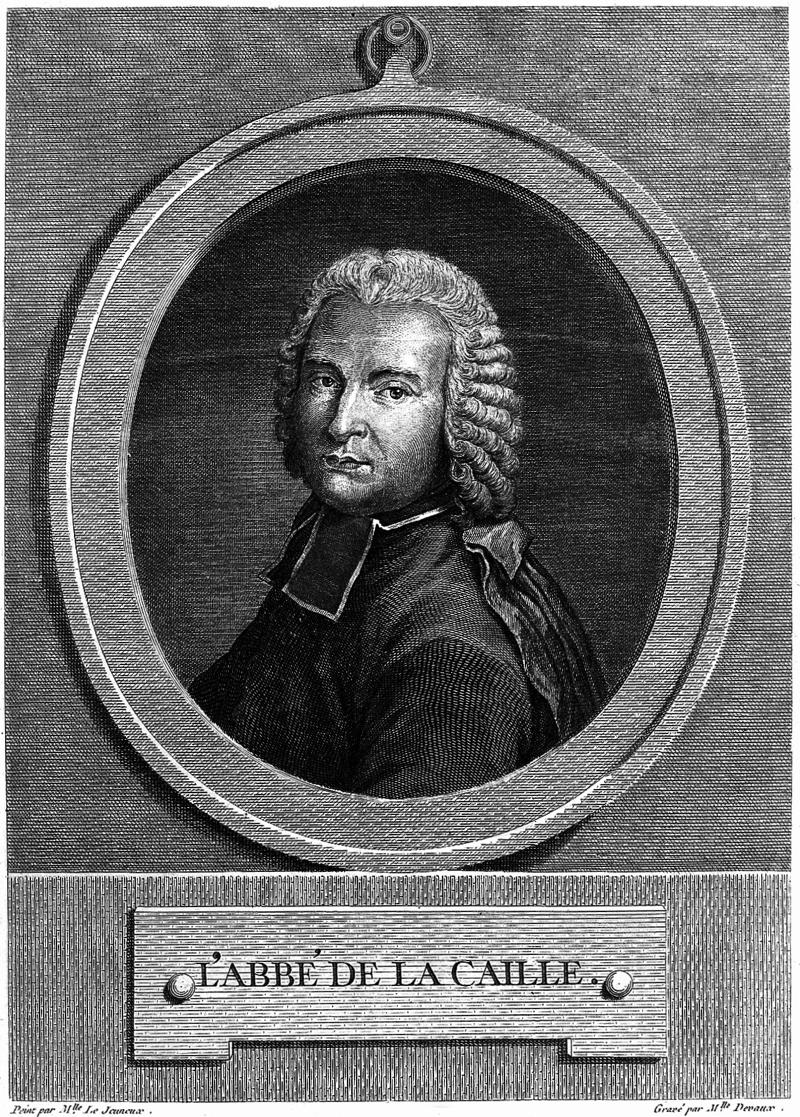

A century later another French cleric-astronomer, the Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, made his way to the Cape during Ryk Tulbagh’s time as Governor of the Dutch colony.

A century later another French cleric-astronomer, the Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, made his way to the Cape during Ryk Tulbagh’s time as Governor of the Dutch colony.

As a mere deacon Lacaille could not offer the Mass and we know little of his relations with any remaining Catholics at the Cape.

There’s no doubt, however, that his contribution to astronomy while in South Africa was significant: Lacaille’s two years of astronomical observation there were prolific in their results. Of the 88 constellations currently recognised by the International Astronomical Union, fourteen were named by Lacaille — including the constellation Mensa (“table”) which took its name from the Latin for Cape Town’s Table Mountain.

Mensa remains the only constellation named after a feature on Earth, so there is a little bit of South Africa that is visible in the night sky anywhere south of the fifth parallel of the northern hemisphere.

Het Spui

Amsterdam is known for its canals, not its public squares, but Het Spui is quite welcoming all the same. The name means roughly sluice or floodgate, pointing to the unsurprisingly watery origins of the place.

At first, it was a canal like any other and was only filled in during the nineteenth century: The first part in 1867 when the neighbouring Nieuwezijds Achterburgwal was filled in, the rest in 1882, two years before the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal.

The Spui (pronounced “spouw” — unless Dawie van die bliksem corrects me) is a focal point surrounded by a number of sights. There’s the Old Lutheran Church, where the Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen met in its early years and still a working congregation today.

There’s the Maagdenhuis, built as a Catholic orphanage and also the seat of the Archpriest of Holland and Zeeland until the restoration of the hierarchy in 1856. The orphanage moved out in 1957 when the building became a bank branch but was purchased by the University of Amsterdam in 1962 to house the administration of the growing institution. (more…)

The Perfect Home Garage

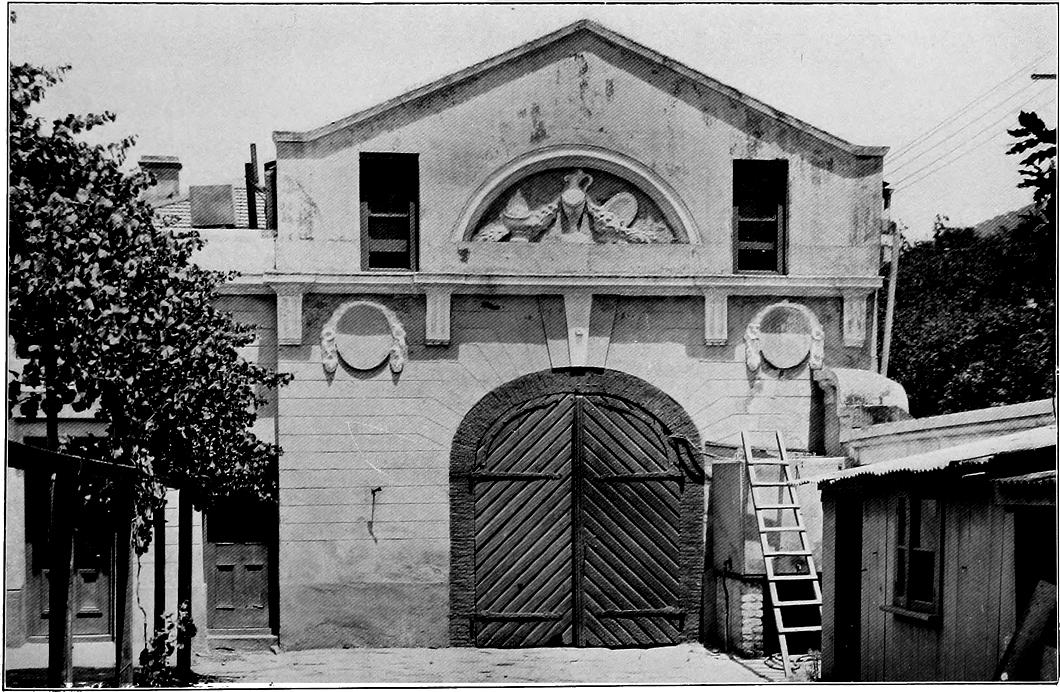

The Coach-House at Saasveld, Cape Town

With all of Suburbia working from impromptu home offices set up in their garages during Covidtide — presumably clinging to their space heaters at this time of year — the subject of the residential garage came up in conversation.

America, being a land of plenty, has the very worst and the very best of home garages. The best are, if a separate structure, often in an arts-and-crafts style and ideally with a floor above perfect for extra storage, conversion to a rental unit, or space for disgruntled teenagers. If attached to the house itself, it is to the side, and only one storey, so as not to distract attention.

The worst, however, are double wide and take up most of the facade, as well documented by McMansion Hell.

My perfect residential garage, however, is not in the States but from the Western Cape. Saasveld was the home of Baron William Ferdinand van Reede van Oudtshoorn, also 8th Baron Hunsdon in the Peerage of England.

In the 1790s, the Baron built the house on his Cape Town estate — between today’s Mount Nelson Hotel and the Laerskool Jan van Riebeeck. The elegant house and outbuildings were almost certainly the work of Louis Michel Thibault, the greatest architect of the Cape Classical style.

Behind the house were two flanking wine cellars linked by a colonnade, at least one of which (above) was eventually put to use as a coach house or garage and photographed by Arthur Elliott.

Unfortunately the house and its grounds fell into ruin and the Dutch Reformed Church bought the site for development and decided to demolish Saasveld. Architectural elements from the house were preserved and eventually re-assembled at Franschhoek where a reconstructed Saasveld serves as the Huguenot Memorial Museum today.

As Mijnheer van der Galiën reports, however, the tomb of William Ferdinand is still at the original site.

Here in Franschhoek the matching wine-cellars-turned-coach-houses are reproduced with their linking colonnade. And I still can’t help but think that — so long as you could fit a Land Rover through the doors — they would make the perfect home garage.

Staats Long Morris

Everyone knows about Gouverneur Morris, scion of one of New York’s great landowning families and given the moniker ‘penman of the Constitution’. As a signer of the Declaration of Independence his half-brother Lewis Morris III was a fellow ‘founding father’. Less well-remembered is his other half-brother Staats Long Morris (1728–1800).

Their father Lewis Morris II was the second lord of Morrisania, the feudal manor that covered most of what is now the South Bronx and has given its name to the smaller eponymous neighbourhood today.

Staats and Gouveneur owe their distinctive Christian names to the family names of their respective mothers.

Lewis II married Katrintje Staats who provided him with four children. After Katrintje died in 1730, Lewis married Sarah Gouverneur, daughter of the Amsterdam-born Isaac Gouverneur. Sarah’s uncle Abraham was Speaker of the General Assembly of the Province of New York, a role Lewis Morris II eventually filled.

Staats was born at Morrisania on 27 August 1728 and studied at Yale College in neighbouring Connecticut as well as serving as a lieutenant in New York’s provincial militia. He switched to the regular forces in 1755 when he obtained a commission as captain in the 50th Regiment of Foot, moving to the 36th in 1756.

Around that time Catherine, Duchess of Gordon, the somewhat eccentric widow of the third duke, was on the lookout for a second husband and Staats — though American, mere gentry, and ten years her junior — met with her approval. They were married in 1756 and Staats moved in to Gordon Castle to live as the Dowager Duchess’s husband.

‘He conducted himself in this new exaltation with so much moderation, affability, and friendship,’ a newspaper reported in 1781, ‘that the family soon forgot the degradation the Duchess had been guilty of by such a connexion, and received her spouse into their perfect favour and esteem.’

With the Duchess’s patronage, Lieutenant-Colonel Staats raised the 89th Regiment of Foot — “Morris’s Highlanders” — from the Scottish counties of Aberdeenshire and Banffshire though she was extremely cross when her new husband’s regiment was despatched to India where it took part in the siege of Pondichery.

In the event, Morris delayed following his regiment to India, leaving England in April 1762 and remaining there only until December 1763. When the young fourth Duke of Gordon came of age the following year, Staats turned his eyes to America and engaged in land speculation there. In 1768 he and the Duchess even went to visit their purchases in the new world, returning to Scotland in the summer of the following year.

With the fourth Duke’s help, and on the eve of the revolutionary stirrings in North America, Staats was elected to the British parliament for the Scottish seat of Elgin Burghs in 1774. He managed to hold on to it for the next ten years. Was this New Yorker the first Yale man to be elected to Parliament? I can’t find any before him, but more thorough research might prove fruitful.

In 1786 he inherited the manor of Morrisania but with the intervening separation between Great Britain and most of her Atlantic colonies General Morris thought it best to sell it on to his brother Gouverneur.

Though he had rejected a future in the world into which he had been born, Staats did return to North America in a professional capacity in 1797 when he was appointed governor of the military garrison at Quebec in what by then was Lower Canada.

Morris died there in January 1800, but his earthly remains were sent back to Britain where he was interred in Westminster Abbey — the only American to receive that honour.

Articles of Note: 15.I.2021

• Autumn and winter are a time for ghouls and ghosts and eery tales. At Boodle’s for dinner two or three years ago I sat next to the wife of a friend and exchanged favourite writers. I gave her the ‘Transylvanian Tolstoy’ Miklos Banffy, in exchange for which she introduced me to the English writer M.R. James — whose work I’ve immensely enjoyed diving into. The inestimable Niall Gooch writes about Christmas, Ghosts, and M.R. James, as well as pointing to Aris Roussinos on how Britons’ love for ghostly tales is a sign of (little-c) conservatism.

• There can be few figures in English history more ridiculous than Sir Oswald Mosley. But the Conservative MP who became a Labour government minister and then British fascist führer-in-waiting was also forceful in his condemnation of the savagery unleashed by the Black-and-Tans. In 1952 a local newspaper in Ireland announced that Sir Oswald and Lady Mosley “charmed with Ireland, its people, the tempo of its life, and its scenery” had taken up residence at Clonfert Palace in Co. Galway. “Sir Oswald,” the paper noted with amazing restraint, “was the former leader of a political movement in England.” Maurice Walsh presents us with the history of Mosley in Ireland.

• The death of the late Lord Sacks, Britain’s former Chief Rabbi, was the subject of much lament. Rabbi Sacks was obviously no Catholic, but his intellect, frankness, and generosity were much appreciated by Christians. Sohrab Ahmari, one of the editors at New York’s most ancient and venerable daily newspaper, offers a Catholic tribute to Jonathan Sacks.

• “Education, Education, Education” has become a mantra in the past quarter-century and while there is a point there’s also a certain error of mistaking the means to an end for the end itself. After all, in the 1930s Germany was the most and highest educated country in the world. At Tablet, probably America’s best Jewish magazine, Ashley K. Fernandes explores why so many doctors became Nazis.

• Fifty years ago the great people of the state of New York rejected both the Republican incumbent and a Democratic challenger to elect the third-party Conservative candidate James Buckley as the Empire State’s senator in Washington. At National Review Jack Fowler tells the gleeful story of the unique circumstances that brought about this victory for Knickerbocker Toryism and how Mr Buckley went to the Senate.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories