World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Felix Meritis

ONE OF MY FAVORITE handsome and dignified, and yet relatively small, buildings is the Felix Meritis on the Keizersgracht in Amsterdam. It has a long and interesting history to accompany the beauty of its design. The ‘Felix Meritis’ was a learned society founded by a number of prominent burghers of Amsterdam in 1777 for the promotion of the arts and sciences in their city. Its name is Latin for ‘fortunate (or more literally, ‘happy’) by merit’. Ten years later, the Felix Meritis purchased four narrow homes on the Keizersgracht and constructed a building, designed by the architect Jacob Otten Husly, on the site. (more…)

The Tragedy of the Falklands War

An article (two versions of which are reproduced here below) recently printed exemplifies one of the tragic aspects of the Falklands War: the Anglo-Argentines who, out of loyalty to their homeland, were forced into waging war against their mother country. The subject of the article, Mr. Alan Craig, happens to be a former student of St. Alban’s College, a fine institution in the Provincia de Buenos Aires (currently celebrating its centenary) which I had the great privilege of briefly attending. (C.f. How Andrew Cusack Became a Tea Drinker). Another sad aspect of the Falklands War is that if there are any two nations which should enjoy the bonds of friendship, it is Britain and Argentina. It is a shame when two countries which should be natural companions, perhaps allies, have deep-seated and long-lasting emotions in the way. (One thinks of Germany and Poland in particular).

Interestingly, Argentine textbooks contain maps of the Falkland Islands in which all the towns and geographical features have contrived names en Castellano. Port Stanley, for example, is called Puerto Argentino, while the Falklands themselves are known to Argentines as las Malvinas.

I remember one day in geography class at St. Alban’s, exhibiting the typical brash arrogance of a youthful Anglo-Saxon, raising my hand, being called on by the teacher, and pronouncing “Sir, I have studied geography all my life, and I spend a lot of time reading maps. I don’t believe there exists such a place called ‘the Malvinas’ though the Falklands…”. I was going to continue that the Falklands “are roughly the shame shape and size and in the same place as this map depicts” (or something to that effect) but I had been interrupted by such a hail of paper, pens, and whatever moveable objects my fellow students could get their hands on (I think Nico, that Russian bastard, had actually thrown a book) that I found it more prudent to take cover underneath my desk rather than continue upon the particular oratorical course upon which I had embarked.

Nonetheless, we pray eternal rest to all the soldiers who fell on those windy isles a quarter-century ago, and that those who survived will live in the peace which their sacrifice has earned for them.

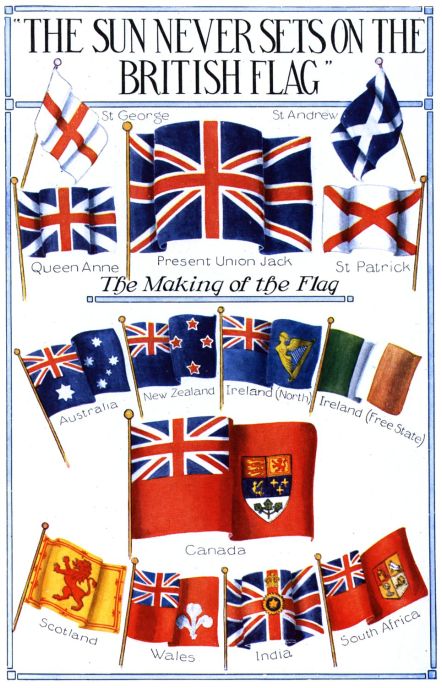

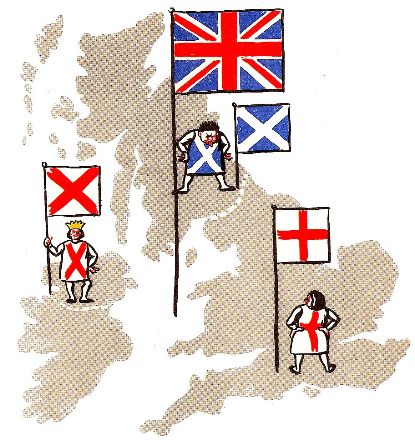

Flags of the British Nations

It is interesting how little-valued accuracy was in the depiction of flags “back in the day”. In this illustration, for example, the flags of Wales and “Ireland (North)” are mere inventions while the Scottish and Indian ones are arguable yet imprecise.

The “Welsh” flag depicted is a red ensign that is defaced with the three feathers of the Prince of Wales.

The “Ireland (North)” flag is handsome, but nonexistent. Northern Ireland had an official flag in use from 1953 until the Parliament of Northern Ireland was prorogued in 1972. (It was never recalled, and has since been superseded by the Northern Ireland Assembly). The flag of “Norn Iron” was a banner of the province’s coat of arms.

The flag of Scotland shown here is not actually the national flag (depicted above as the “St. Andrew” flag) but rather the Scottish royal standard, which is often (and improperly) used as an alternative national flag.

The Indian flag depicted is actually the flag of the Viceroy of India, which (admittedly) was sometimes used as a national flag for India. More often, however, a blue or red ensign was used, defaced with the Star of India.

The Canadian flag depicted here was changed in 1957, when the arms of Canada were themselves changed. The maple leaves in the bottom compartment of the sheild were specified to be “gules” (red). Up to that point, they had previously almost always been rendered “vert” (green). The Canadian flag itself was very controversially and unpopularly replaced by Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson with the Maple Leaf Flag. The Leader of the Opposition, the Rt. Hon. John Diefenbaker, derided the Liberal premier’s decision:

“We have had a flag. Flags can be changed. But flags cannot be imposed — the sacred symbols of a people’s hopes and aspirations — by the simple capricious personal choice of a prime minister of Canada. Now then, whenever the overwhelming majority of Canadian people want a new version, and when the design is meaningful and acceptable to most Canadians, that’s democracy. … I asked him [Prime Minister Pearson] this question: as to whether or not, under the circumstance, he would permit or he would arrange for a national referendum and his answer was no.”

Breaking the Mold in Quebec

WAS I THE only one south of the border who was glued to the computer screen watching CBC TV’s streaming online coverage of the Quebec elections? The results of the vote for the provincial parliament proved surprisingly exciting, perhaps even dramatic. The star of the evening was the stunning success of Mario Dumont’s Action Democratique du Quebec, breaking out of their small strongholds and winning seats across the entire province. They even made inroads in the leftist bastion of Montreal. While they did not win any seats on the island of Montreal, the came second in a number of ridings (as constituencies are known in Canada), and took a number of seats in the Montreal suburbs. But perhaps I should give a little background to what’s going on. (more…)

Hail Glorious Saint Patrick

THE FEAST OF IRELAND’S patron saint is an occasion for parading if ever there was one. For this, we can send part of our thanks to the British Army, which happened to initiate the most famous St. Patrick’s Day Parade of them all, namely, New York’s. It was 1762 when a number of Irish troops in the service of the Crown took it upon themselves to parade up Gotham’s own Broadway on the 17th of March. (More recently, the Duke of Edinburgh was invited to partake in the New York parade during his 1966 visit to America). Despite the lamentable outbreak of separatist republicanism in much of Ireland, the sons of Erin continue to take the Queen’s shilling and serve proudly in Her Majesty’s forces, and true to form they are sure to mark their patron’s feast day.

The Knickerbocker Greys

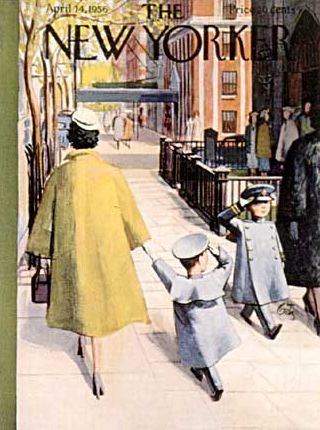

The Knickerbocker Greys, the Upper East Side corps of cadets, is celebrating its 125th year in existence. Both the Times and the Sun have featured articles on the Greys:

‘Celebrating 125 With the Knickerbocker Greys‘ by Gary Shapiro (The New York Sun)

‘Manhattan’s Littlest Soldiers‘ by Eric Königsberg (The New York Times)

Above: A mother mends a cadet’s uniform.

Below: Cadets assembled in an Armory corridor. (Note the interior scaffolding due to the State’s grievous neglect of the Armory).

The ‘CNN Effect’

A number of International Relations students at St Andrews have created this video (5:18) illustrating what is known in that field of study as the ‘CNN effect‘ on a crisis in fictional ‘Berniestan’.

Lord Glenavy

Sir James Henry Mussen Campbell, Bt., 1st Baron Glenavy, PC, QC. was born in Dublin in 1851. Campbell graduated from the University of Dublin (Trinity College) a Bachelor of the Arts in 1874. He was called to the Irish bar in 1878, being made a Queen’s Counsel in 1892.

Campbell was elected to Parliament in 1898, being called to the English bar a year later. He was made Solicitor General for Ireland in 1903, as well as being appointed an Irish Privy Counsellor. He rose to become Lord Chief Justice of Ireland in 1916, being made a baronet the following year, and Lord Chancellor of Ireland the year after that (1918). Sir James was ennobled as 1st Baron Glenavy upon relinquishing office in 1921.

Ireland was partitioned in the following year, and Lord Glenavy became the first Cathaoirleach of Seanad Éireann (Presiding officer of the Irish senate). In 1923, he chaired the judicial committee investigating the establishment of a new courts system for the Irish Free State. His proposals were implemented the following year in the Courts of Justice Act 1924, forming the Irish courts as they remain today.

Having served one six-year term in the Seanad, he did not seek re-election in 1928, and died three years later in 1931. Holding the largely honorary position of President of the College Historical Society (“the Hist”), Dublin University’s debating society, from 1925, he was succeeded upon his death by his fellow Irish Protestant, Douglas Hyde, who himself later became the first President of Ireland from 1938 until 1945.

The Men Who Saved Quebec

The British Crown’s toleration of Catholicism in Quebec was cited by the rebel colonists of the 1770’s as, ironically, an ‘intolerable act’. That the Church of Rome, that bastion of backwards conservatism and slavish hierarchy, could be tolerated in the lands under the power of the British parliament riled the Whigs—the enlightened liberal progressives of the day. Indeed, Benjamin Franklin was even so foolish as to go to Quebec as an emissary of the ‘Continental Congress’ to persuade the natives to rebel against the Crown; Congress’s proposals to ban Catholicism and prohibit the use of the French language ensured he was not successful.

The modern orthodox opinion of historians on the Quebec Act of 1774—the act that granted toleration to the Church—is that it was merely a persuasive exercise to keep les Canadiens from rebelling. A 1989 book challenged this perspective, arguing instead that a handful of British aristocrats were determined to ensure that Quebec did not become another Ireland: where Protestant ascendancy was thrust upon an unwilling nation of Catholic nobles, merchants, and peasants.

The following review by Gary Caldwell was published in a Canadian journal in 2001.

|

Philip Lawson.

The Imperial Challenge: Quebec and Britain in the Age of the American Revolution. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. 192 pages. US$27.95. |

WHY REVIEW A BOOK published twelve years ago? I will explain. But first, let me tell you what it’s about.

When Britain took possession of Canada at the Treaty of Versailles in 1763, it faced an “imperial challenge:” how to integrate into the empire a society fundamentally different from England – in language, religion, and legal and political institutions. At the time, England was vigorously intolerant of Roman Catholicism or “popery,” the religion of its major enemies, France and Spain. British Protestantism was closely tied to the dominant Whig political ideology born of the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89. This doctrinal legacy prescribed that all British subjects were possessed of very definite and equal liberties, liberties endowed upon and limited to those who conformed to the Whig-Protestant definition of being British.

Hence the problem of 1763. English law and constitutional practice allowed only for protestant public officials and elected representatives. This meant excluding the entire French-speaking population, some 70,000 to 80,000 (the “new subjects”) as compared to some 300 Protestants established in the colony (the “old subjects”).

There were two schools of thought as to what should be done. The Whig position, favoured by much of the English political leadership and commercial class on both sides of the Atlantic, was not to accommodate the new subjects. It amounted to an attempted destruction of the local culture and to exclusion of the French-speaking population from all juridical, political and social positions, the hoped-for consequence being assimilation in one, perhaps two, generations. In short, what had been imposed in Ireland with the “protestant ascendancy.”

The opposing school of thought, still marginal in 1763, believed such a policy both impracticable and undesirable. James Murray, Lord Shelburne, Lord Dorchester (Gary Carleton), H. T. Cramahe, Alexander Wedderburn, Lord Mansfield and William Knox not only held that a Protestant ascendancy in Quebec would ruin the colony, they also believed that Quebec society was deserving of being preserved. Murray and Dorchester, who knew Quebec and its people, were adamant: the Canadians were a good “race”—in Murray’s words, “perhaps the best and bravest race on the globe” (p. 48)—and if protected they and their society would flourish and be loyal to the Crown. As it happened, all of these administrators and Crown legal officers, with the exception of Cramahe, were Anglo-Irish or Scottish; not one of them was of English origin.

But how were the Canadians and their culture to be accommodated? There were, as Lawson demonstrates, three distinct dimensions to this accommodation. The first was to respect the prevailing legal code and custom in civil and property matters; the second, to refrain from putting into place an English representative assembly because it would be the instrument of the 300 or so English and American voters in the colony. By far the most important was the third dimension, tolerance in Quebec of Roman Catholicism, which meant the nomination of a Bishop, the tithe and the right of Catholics to hold public office. Dorchester and the others successfully won these concessions in London by 1770, and they were contained in the Quebec Act in 1774, to the horror of much of English public sentiment, and especially the Americans who were more resolutely against “popery” and more Whig than the English themselves.

When Benjamin Franklin arrived in Montreal in 1775 with the invading army of the Continental Congress, he carried secret orders to ban the popish religion and the French language. Fortunately, the Americans were stopped in Quebec by no other than Dorchester, back from getting the Quebec Act through Parliament. At the head of an army of old and new subjects he broke the 1775-76 siege of Quebec.

Lawson’s interpretation is insightful in putting the events into the context of the Irish question. The major players in promoting the accommodation that became the Quebec Act had in mind “the Irish Imbroglio,” and were determined not to repeat the error of the “protestant ascendancy” in Ireland. The Quebec Act emerges clearly as the culmination of thoughtful and courageous policy formulation, a model of generous statesmanship. Hence, as Lawson goes on to argue, the “toleration” of Roman Catholicism in the Quebec Act paved the way for the British Acts of Toleration of 1778.

Lawson also helps understand why Murray, Dorchester and the others came to the conclusions they did about the Canathan problem. These men were essentially empirical conservatives who found the answer “in the past”—Quebec society as they had known it in the 1760s—and the “elastic nature of the British Constitution.” And here Lawson runs smack into the prevailing wisdom in Canadian historiography.

Lawson is insistent on the coincidental nature of any link between the Quebec Act and the American Revolution, affirming that there is no evidence that the inspiration for the Quebec Act was to placate the Canadians so as to keep them apart from the Americans. As this alleged link is one of the most tenacious myths in the Canadian historical consciousness, it is worth citing Lawson:

What can be done to dispose of this myth once and for all? Fifty years ago both Coupland and Burt said that they could find no evidence to justify such an assertion with Lanctot repeating the message in the 1960s, and nothing has yet come to light to contradict them (pp. 123-124).

When I first read this book in the early 1990s and realized how revolutionary his thesis was, I contacted Lawson to talk about his work. In passing, I mentioned that I supposed that The Imperial Challenge must have created quite a controversy in Canadian academic circles. His reply was “No, it has attracted very little attention in Canada.” (I never saw him again. I had arranged to see him a few years later, but just before I arrived in Edmonton he was admitted to hospital for terminal cancer and died shortly afterwards.) In subsequent years, I have been to McGill-Queens Press in Montreal to buy copies of his book to give to friends. Inquiring as to sales, I was told that only a few hundred copies had been sold. And, so far, I have encountered only one reference to Lawson’s book (in Yves Lamonde’s Histoire sociale des politiques au Quebec).

I was curious enough to go back recently to the reviews written when the book came out. There were 16 in Canada in French and English, in the United States and in the United Kingdom; all reviewers were quite positive except one (who wrote two of the reviews). They all commented positively on the extent and depth of the documentation, as well as the fresh reading from parliamentary debates, the personal archives of the principal players, and the press of the day. As for his interpretation of how the Quebec Act came to be, there is no suggestion that he was wrong in any respect. The negative reviewer suggests only that it is pretentious of Lawson to think he has added much to existing work on the Quebec Act. Of the 15 reviewers, a full half explicitly accredit Lawson with drawing out the intention of avoiding the error of Ireland.

Why, then, did a book, critically acclaimed by the author’s peers, which sheds considerable light on a pivotal period in the history of Quebec and Canada, drop out of sight in Quebec, and I suspect in the rest of Canada? Lawson calls into question the conventional wisdom on a very important subject in Canadian history, and no one takes notice. For instance, two prominent Canadians, Gerard Bouchard and John Raulston Saul, social thinkers who are presently reinterpreting Canadian history, make no mention, to my knowledge, of this book. A book that should have caused waves has generated scarcely a ripple.

Perhaps my assessment, as a non-professional historian, is faulty and I would welcome a demonstration of where I have erred. What are the factors that explain the untimely eclipse of Lawson’s work? Could it be simply that Canadian intellectual discourse is shallow, that a seminal work can be dropped into the water and hit bottom generating nothing more than a superficial ripple of perfunctory reviews and listings in compendiums? This is one possible explanation; a more certain explanation lies in ideology.

The ideological axe, starkly put, goes as follows. Quebec’s nationalist, republican-leaning contemporary intellectuals are loath to entertain the idea that a coterie of British Conservatives (half of them aristocrats) literally saved Quebec society by helping to keep it strong enough to withstand the renewed neo-liberal assault led by Lord Durham three quarters of a century later and, then, begin to rehabilitate the Quebec polity (under British institutions) in 1867. Such an idea being beyond the pale (again, the ghost of Ireland), they maintain the myth that the Quebec Act was political opportunism inspired by the American threat. What will it take for Quebec nationalist thinkers to recognize and appropriate the historical reality that Dorchester twice—in the Quebec Act and the siege of Quebec—saved Quebec? It is no exaggeration to assert that, had it not been for this one Anglo-Irish aristocrat, Quebec would likely have become anglicized and, subsequently, integrated into the American empire.

As for English-speaking Canada, the current crop of orthodox historians has long consigned our British imperialist past to the Marxist dust-heap of history: nothing good could possibly have come of it, all imperialisms being, by definition, bad. They are not about to disturb their orthodoxy that in contrast to Imperial Britain, which was incapable of any genuine sympathy for Quebec—only Canadian nationalist intellectuals are enlightened and respectful of Quebec society. So, they too maintain the “political opportunism” interpretation of the Quebec Act, despite its having been refuted by Lawson and his predecessors. Essentially, what we are seeing is a refusal to acknowledge a debt owed to dead white male Protestants (from Ireland and Scotland). But gratitude is not, as the contemporary French philosopher Alain Finkielkraut has pointed out, a hallmark of modern progressive thinkers.

I write this review knowing full well that it is too late for Lawson’s work to be rehabilitated. The Imperial Challenge is among the titles in this year’s McGill-Queen’s clear-the-warehouse sale.

Previously: Hitchcock in Quebec

And the natives rejoiced…

One can find such amazingly random things on Youtube. Here we have a clip (3:09) of the native Fifers of Bell Baxter High School, of which the President of the St Andrews University Catholic Society is a distinguished alumnus, dancing my favorite reel (the name of which eternally escapes me).

And then there’s this clip (2:07) of Peter Sellers (or is it the Maximum Leader?) reciting “It’s Been A Hard Day’s Night” in the manner of Olivier:

The Knights of Malta Ball 2007

THE MONTH OF FEBRUARY returns, and so too the Knights of Malta Ball with its requisite sojourn to Edinburgh. If I have a confession to make, it is that I am a creature of habit, and having gone the past three years, I didn’t see why the intervening distance of the Atlantic Ocean should make any particular difference this year. If I may make another confession, it is that I am incapable at organizing things competently, and of course left sorting out tickets to the last week. “Impossible,” quoth Zygmunt Sikorski-Mazur when I contacted him. “Too late I’m afraid, and there is even a waiting list of people who’ve paid up just in case tickets become available”. Well, I had accommodated myself to the concept of heading up to St Andrews and having a grand night out instead, but luckily C. came to the rescue. “Perchance,” saith the youthful Old Harrovian, “I have a spare ticket and you can have it if you wish”. Well, that settled it.

Carried off by taxicab to the Assembly Rooms in George Street from the similarly-monikered Assembly bar in Bristo Square, it was something of a disappointment to find the fine Georgian building veiled in scaffolding and lacking the usual looming Scottish standards of the Order (smaller version seen here) and the flanking flags hanging, floodlit, from the splendid façade. Nonetheless, the Assembly Rooms have been in need a fixing-up for some time now, so it’s a relief to know that the City of Edinburgh have finally coughed up the dough. Interior restorations are to follow in the coming years, but then where will the Ball during such a restoration? Ed Monckton suggested the Castle as an acceptable substitute, and I’m inclined to agree.

It was quite the enjoyable ball, as per usual. His Eminence the Cardinal Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh was affable as ever. (Last year, a photo of His Eminence, Lt. Col. Bogle, Abigail, and myself at this very event made it onto the social page of Scottish Field. I hope that is as far as my life in the limelight goes!). I ran into Fra’ Freddie (Crichton-Stuart) and he exclaimed “What are you doing here!”, though he subsequently admitted that his “little spies” had, actually, informed him I would be popping over from New York. Ed Monckton shared an amusing tale of his late grandfather and the Duke of Wellington commandeering a tank to gain entry to a public house and disengaging street lamps by means of firearms. California’s own Chevalier Charles Coulombe, of course, talked to everyone, even the bouncers, who had a decidedly mafioso look to them this year. I, forgetfully, neglected to pick up a pack of Dunhills beforehand, but Gary Dench and I ran into Albert and he kindly offered his brand: an excellent, unfilitered variety of (naturally) German origin.

One of the unintended consequences of the Scottish smoking ban is an increase in socialization: a greater appreciation of the brotherly bonds of nicotine intake. Now that we of the smoking habit are forced to congregate outside entrances you have an instant bond of solidarity with complete strangers. I met an Austrian fellow named Camilo, an Edinburgh University student, and we agreed on the excellence of the Scottish system of higher education. (If one could dignify it with that term; perhaps ‘style’ is a better word than ‘system’). As it turned out, he had also spent some time in dear old Argentina, and so we swapped stories of the people and their particular ingenuity.

Later, Zygmunt introduced me to his son Nicholas, a very intelligent fellow who sounds terribly Scottish because he was educated in France rather than England with all the other Scots. (Alright, some Scots are educated in Scotland. There are Gordonstoun, Fettes, Glenalmond, and elsewhere needless to say). There were also two young Cypriot ladies, sisters if I recall correctly, who were very charming and whom we managed to drag onto the dance floor for a reel (and one of whom even managed to drag me onto the dance floor later in the evening). Typically, their names have been filed away in some deep but, alas, inaccessible fold of my brain. At any rate, we all agreed that the Turks ought to be given the boot. (Seems to be a recurring theme in European history, eh?).

Jamie Bogle was extremely late in arriving, and it turned out there was a story behind it. The trains from London were a typical shambles and there was every type of delay imaginable. Having used his mobile to make a phone call, the good Lieutenant Colonel was approached by another fellow asking if he could make a call. Jamie happened to overheard the fellow discussing “chambers” and so inquired if he (like Jamie) was a lawyer. The chap applied in the affirmative. Later in discussion, they discovered they were both actually heading to Edinburgh, and furthermore, as it turns out, to the Knights of Malta Ball! They realized they would both be terribly late, and so resigned themselves to the bar car, where they drank the train dry of champagne. The fellow’s name is Christopher Boyle, and he and his wife made for some excellent conversation, along with Amanda Crichton-Stuart, whom I singularly failed when sent to procure cigarettes for, as the few newsagents along George Street had shut by that time in the evening. I did, however, introduce her to Albert, who offered one of his cigarettes, and happily they seemed to get on well. Unhappily, the Sunday following, Albert’s Jack Russell terrier (who goes by the name of Cicio) took serious umbrage with my throwing a stick around with a female German shepherd Cicio clearly had eyes on. He ran up to me and bit me in the leg! Albert was very apologetic, and with a rolled-up newspaper and a “kommen zie here!” forced Cicio to likewise apologize. You know, as he lay prostrate before me with a teary look in his eye, I actually felt pity for the blighted creature which, only moments before, had planted its jaws on my right calf! Well, these things do happen.

On a more positive note, I actually won two prizes in the tombola raffle! A china mug bedecked with the insignia of the Sovereign Military and Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta and a placemat with an unrecognizable coat of arms emblazoned upon it. I shall have to get my heraldic detectives to work investigating the bearer of the arms; needless to say I will be quite prepared should he come for dinner.

EVENTUALLY, THE BELLS tolled and the staff encouraged us to exeunt the Assembly Rooms and we duly complied. There was then some prolonged pondering about after-parties. Zygmunt, Nicholas, and myself made a foray into the hopping Opal Lounge across the street, but I found it not to my particular liking (too loud! too crowded!) and thus decided to retire to bed. All in all a much-enjoyed evening. I congratulated Henry Lorimer on the night for having pulled it all off. “You have no idea how glad I’ll be when tomorrow comes!” was his response. Well, all the organizers deserve our thanks and appreciation. I have been to the ball four years in a row now and each time it has been excellent, though, because of the variety of parties I’ve gone with, excellent in very different ways. I wonder if I will attend next year? I hope so, as the more excuses to go to Edinburgh I have, the happier I shall be.

Bon Voyage

Heading to Scotland for a little bit, then down to Somerset for a spell. Dino Marcantonio, you’re in charge!

Hitchcock in Québec

QUÉBEC, THAT STRANGE and charming province, is a most intriguing nation. It is where the British, French, and American tendencies clash and combine to form that most peculiar of all American varieties: le Québécois. Of course, since the 1960s Québec has become more French; no, not more French but more like France in that every year it plunges deeper into the depths of self-loathing: that hatred of one’s own tradition and history which has so marked out “the new Europe”. It is a race to assert one’s self by destroying any living connection to one’s past. Un jeu du fou. More’s the pity, as this once-vibrant melting pot of traditions expressed itself in interesting ways.

A splendid display of this Québec can be found in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1953 drama I Confess. The film had been recommended to me often and I finally got around to seeing it tonight. I won’t give away any of the plot, which is a good one, but Hitchcock lives up to his reputation with his excellent framing of the scenes. (Though I must admit, half of it is merely the settings in the Ville de Québec themselves). They include a peek into the Québécois Parliament. Above the Speaker’s dais is displayed not only the Sovereign’s arms, but also a crucifix, exhibiting our loyalties both temporal and spiritual. In the court room you find yet another blend of the Anglo and the French. As you no doubt recall from our handy little map, Quebec is a country with a mixed legal system. Founded as Nouvelle-France it had the civil system derived from the Romans. Captured by the British and later transformed into part of the Canadian Confederation, it has accrued layers of the Common Law so dear to we Anglos. The officials of the court wear British-style robes — the judge even has a tricorn hat — but over the jury looms a large crucifix. English government and French culture tempered by Catholic truth; not a bad mixture.

Anyhow, if you haven’t seen the film yet, here are a few snaps to enjoy until your Hitchcockian thirst is satiated. (more…)

Un Écossais en France

CHARLES GRANT, VICOMTE DE VAUX, was a Frenchman of Caledonian extraction who served as a sous-lieutenant in the Scots Company of the Garde du Roi, eventually rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. A cadet branch of the Scottish clan, the Grants in France made sure to maintain links with their kinsmen in the old country. Abbé Peter Grant helped Sir James Grant, 8th Bt., commence an art collection while Sir James was on the Grand Tour in 1759-60. Abbé Grant’s nephew, Baron Grant de Blairfindy, was a fellow Catholic and Colonel in the Légion Royale of Louis XVI.

In a letter to Sir James, who was Chief of the Grants, Blairfindy described their fellow kinsman the Vicomte de Vaux as “a clever, brave officer, polite in company… as brave as his sword,” though, rather disappointingly, the Baron adds that the Vicomte “never drinks”. De Vaux himself took a keen interest in his extended family, and when the terrors of the French Revolution forced him into exile in London, he published there his Mémoires de la Maison Grant depicting the history of the clan. (more…)

County Confusion

The Permanent Revolution in Modern Britain

ONE OF THE CURIOUS things about folks in Britain today is that they are not too sure about where they live. And often, when they are sure, they’re not entirely correct. I have a friend from Abingdon in England and for ages she told me that she was from Abingdon in Oxfordshire. Imagine my surprise to discover that Abingdon is not only in Berkshire, but it’s traditionally the county town of Berkshire! The trouble originates in the reforms of local government which have ensured perpetual confusion amongst the populace, and have been pretty much ongoing for the past forty years — an example of permanent revolution that would make Fidel Castro envious.

ONE OF THE CURIOUS things about folks in Britain today is that they are not too sure about where they live. And often, when they are sure, they’re not entirely correct. I have a friend from Abingdon in England and for ages she told me that she was from Abingdon in Oxfordshire. Imagine my surprise to discover that Abingdon is not only in Berkshire, but it’s traditionally the county town of Berkshire! The trouble originates in the reforms of local government which have ensured perpetual confusion amongst the populace, and have been pretty much ongoing for the past forty years — an example of permanent revolution that would make Fidel Castro envious.

The counties of England were created quite shortly after the beginning of time. The ancient sages debated voiciferously whether the Author of Creation initiated them on the eighth or the ninth day. (Curiously, the Venerable Bede is not known to have taken either position). They remained completely and utterly unchanged until the Victorians (a cohort quite bent on the idea of civic improvement) had a fiddle with them in the 1880s. From then, there were only periodic adjustment until the 1960s, when the forces of cultural revolution (the monotony monitors, as my old Latin teacher called them) demanded change in every quarter. The counties of England, sadly, did not escape their Sauronic all-seing eye.

Lancashire, in better days.

The real problem which arose was that the traditional counties were, thankfully, never abolished, but that administrative units were created which often shared the same name as an historic county, but with different boundaries. Despite the fact that the county didn’t change, the movement of cities, towns, villages, hamlets, barns, and rabbit warrens between various administrative units brought much confusion as to whether a given location which was in one particular place or another. Thus the people of the previously self-governing Bootle in Lancashire found themselves merged into the metropolitan district of Sefton, which itself became part of the metropolitan ‘county’ of ‘Merseyside’. Meanwhile, the southern part of Gloucestershire and the northern part of Somerset were merged into a new ‘county’ created ex nihilo and baptised with the name of ‘Avon’. So a town could be in real Somerset but administrative Avon. All a bit maddening and confusing. (more…)

A Good Look at ‘Modern Britain’

The brilliant Mr. Peter Hitchens ruminates on the old Russian bear, and relays to us this account of the state of Britain today from the point of view of a Russian journalist:

Under its corrupt government, which is widely believed to sell seats in the upper house of parliament in return for contributions to ruling party funds, the once-free nation of Britain is rapidly turning into a police state. Pre-trial detention, once limited to 72 hours, is being repeatedly extended to far longer periods. Old rules about the accused being innocent until proved guilty are being cast aside. The right to silence has been abolished and so has the law which prevented anyone being tried twice for the same offence. The police increasingly take action against individuals for expressing opinions which defy ‘political correctness’, the official orthodoxy of the British state. The major Churches claim that new laws discriminate against their freedom of conscience.

The streets are under perpetual surveillance by closed-circuit TV cameras recording every action. The citizens are shortly to be issued with internal passports similar to Russian ones, and will be compelled to provide their fingerprints to their authorities. Schoolchildren are already being fingerprinted on such pretexts as allowing library access. The police increasingly use arrests – not followed by charges – to harass those they wish to pursue – and anyone arrested – whether convicted or not – is now compelled to give a DNA sample. As a result, Britain now has the most comprehensive DNA records of its population, anywhere in the world. Many state bodies now have the power to search people’s homes, and the old maxim that ‘An Englishman’s Home is His Castle’ is now so untrue as to be laughable.

Elections are still held, but are a sham in which all the parties have more or less the same policies. The main political movements, which have lost much of their popular support, are kept going by state subsidies and contributions from millionaire businessmen. The main state-owned broadcasting system is slavishly loyal to the government and keeps minority viewpoints off the air, or treats them with contempt and derision, while the other channels mostly purvey low-grade pornographic entertainment, so-called ‘reality’ shows of stunning banality, old movies and sport.

Meanwhile, actual crime is out of control, though citizens are legally prevented from many actions of self-defence and a government minister recently advised Britons to ‘jump up and down’ if they saw an old woman being attacked in the street, in the hope of distracting the attacker. This is the country which lectures Russia about ‘civil society’ and ‘human rights’.

Appeal to the Holy Father

From the British Isles

This appeal was recently sent to Pope Benedict XVI from a number of British intellectuals and public figures. (Source: Rorate Caeli).

In 1971 many leading British and international figures, among whose number were Yehudi Menuhin, Agatha Christie, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Nancy Mitford, Graham Greene, Joan Sutherland, and Ralph Richardson, presented a petition to His Holiness Pope Paul VI asking for the survival of the traditional Roman Catholic Mass on the grounds that it would be a serious loss to western culture. The then Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Heenan himself appealed to Pope Paul for the continued celebration of the traditional Mass. The full text of this appeal in 1971 was:

“If some senseless decree were to order the total or partial destruction of basilicas or cathedrals, then obviously it would be the educated – whatever their personal beliefs – who would rise up in horror to oppose such a possibility. Now the fact is that basilicas and cathedrals were built so as to celebrate a rite which, until a few months ago, constituted a living tradition. We are referring to the Roman Catholic Mass. Yet, according to the latest information in Rome, there is a plan to obliterate that Mass by the end of the current year. One of the axioms of contemporary publicity, religious as well as secular, is that modern man in general, and intellectuals in particular, have become intolerant of all forms of tradition and are anxious to suppress them and put something else in their place. But, like many other affirmations of our publicity machines, this axiom is false. Today, as in times gone by, educated people are in the vanguard where recognition of the value of tradition in concerned, and are the first to raise the alarm when it is threatened. We are not at this moment considering the religious or spiritual experience of millions of individuals. The rite in question, in its magnificent Latin text, has also inspired a host of priceless achievements in the arts – not only mystical works, but works by poets, philosophers, musicians, architects, painters and sculptors in all countries and epochs.

“Thus, it belongs to universal culture as well as to churchmen and formal Christians. In the materialistic and technocratic civilisation that is increasingly threatening the life of mind and spirit in its original creative expression – the word – it seems particularly inhuman to deprive man of word-forms in one of their most grandiose manifestations. The signatories of this appeal, which is entirely ecumenical and non-political, have been drawn from every branch of modern culture in Europe and elsewhere. They wish to call to the attention of the Holy See, the appalling responsibility it would incur in the history of the human spirit were it to refuse to allow the Traditional Mass to survive, even though this survival took place side by side with other liturgical reforms.”

This appeal in 1971 came at a crucial time in the history of civilisation when the future of the traditional Latin “Tridentine” Mass was in jeopardy. Pope Paul VI graciously acknowledged this appeal and the traditional Mass was saved, at least in England and Wales. Since this momentous appeal in 1971 the traditional Latin Mass has prospered once again among the faithful worldwide and is now celebrated in almost every country in the world. Now, in 2007, there is great hope and expectation that this treasure of civilisation will be freed from its current restrictions. We, the signatories of this petition, wish to associate ourselves to the sentiments expressed in the petition of 1971 which, perhaps, are even more valid today, and appeal to His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI in 2007 to allow the free celebration of the traditional Roman rite of Mass, the Mass of Ages, the Mass of Antiquity, on the altars of the Church.

Miss Madeleine Beard, M.Litt. (Cantab).

Dr. Mary Berry CBE, Founder of the Schola Gregoriana in Cambridge.

James Bogle, TD, MA, ACIarb, Barrister, Chairman of the Catholic Union of Great Britain.

Count Neri Capponi, Judge of the Tuscan Ecclesiastical Matrimonial Court.

Fr. Antony F.M. Conlon, Chaplain to the Latin Mass Society.

Julian Chadwick, Chairman – The Latin Mass Society of England and Wales.

Rev. Fr. Ronald Creighton-Jobe, The Oratory, London.

Fra’ Fredrik Crichton-Stuart, Chairman CIEL UK.

Leo Darroch, Secretary – International Federation Una Voce.

Adrian Davies, Barrister.

R.P. Davis, B.Phil., M.A., D.Phil (Oxon), retired senior lecturer in Ancient History, Queen’s University of Belfast; translator/commentator on the Liber Pontificalis of the Roman Church.

John Eidinow, Bodley Fellow and Dean, Merton College, Oxford.

Jonathan Evans MEP, Vice Chairman Catholic Union of Great Britain.

Fra’ Matthew Festing, OBE, TD, DL. Grand Prior of England of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.

The Right Honourable Lord Gill, Lord Justice Clerk of Scotland.

Dr. Sheridan Gilley, Emeritus Reader, University of Durham.

Dr. Christopher Gillibrand, MA (Oxon).

Rev. Dr. Laurence Paul Hemming, Heythrop College, University of London.

Stephen Hough, Concert Pianist and Composer.

Neville Kyrke-Smith, National Director, Aid to the Church in Need UK

Prince Rupert zu Loewenstein, President of the British Association of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. KCSG.

James MacMillan, CBE, Composer and Conductor.

Anthony McCarthy, Research Fellow, Linacre Centre for Healthcare Ethics.

Mrs. Daphne McLeod, Chairman – Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice.

Anthony Ozimic, MA (bioethics).

Dr. Susan Frank Parsons, President, Society for the Study of Christian Ethics (UK) and Co-Founder of the Society of St. Catherine of Siena.

Dr. Catherine Pickstock, Lecturer in Philosophy and Religion; Fellow – Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

Dr. Thomas Pink, Reader in Philosophy and Director of Philosophical Studies, Kings College, London.

Piers Paul Read, Novelist and Playwright; Vice-President of the Catholic Writers’ Guild of England and Wales.

The Rev’d. Dr. Alcuin Reid, Liturgical Scholar and Author.

Nicholas Richardson, Warden of Greyfriars Hall, Oxford.

Prof. Jonathan Riley-Smith, retired Dixie Professor of Ecclesiastical History, Cambridge University.

Fr. John Saward, Lisieux Senior Research Fellow in Theology, Greyfriars, Oxford University.

Dr. Joseph Shaw. Tutorial Fellow in Philosophy, St. Benet’s Hall, Oxford University.

Damien Thompson, Editor-in-Chief, The Catholic Herald.

Three Cheers for Nigel Farage

I STAND IN AWE of Nigel Farage. He is the oratorical master of the European Parliament, which, of course, doesn’t count for much since about as much attention is paid to the European Parliament as was to the Reichstag in Nazi Germany. This is despite the fact that the majority of laws passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom are not actually initiated by British MPs, but rather rubber-stamped from Brussels on high.

If you’re asking yourself “Who is this fellow?”, then I should tell you that Farage is the somewhat-hokey leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party, the party which should get the votes of all visitors of this site. These days, one should be a Tory every day of the year except Election Day. The next general election is especially important as it must be proved to the bigwigs in the Conservative Party that Europe matters. Labour will likely win the next election anyhow (it’s even possible for the Tories to have 10% more of the popular vote but still come out with fewer seats than Labour), and the more seats that the Tories lose because just enough people voted UKIP instead of Conservative will hopefully turn the party round. (more…)

The Many Faces of R.J.E. Bradley

It is one of the wonders of Facebook that with a touch of the button you can find hundreds of photos of your friends. Among my compadres, none have quite the varying range of facial expressions as one R.J.E. Bradley. (Actually, you’ve met him, and his delightful parents, before, remember?). If any of you fear that 1980s-Wall-Street-style decadence has gone the way of the dodo, fear not, for Bradley keeps it alive in St Andrews. He can usually be found doing something outrageous at one of the numerous charity fashion shows, or perhaps enlivening a meeting of the Global Investment Group, or else displaying his wit in some other corner of the auld grey toon.

Previously: The Last Sunday

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories