World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Lafayette at the Seventh

For the first century or so in the history of the United States, there was no more popular Frenchman in America than the Marquis de Lafayette. This nobleman of the Auvergne was an officer in the King’s Musketeers aged 14 and was purchased a captaincy in the Dragoons as a wedding present aged 18 in 1775. Within a year the rebel faction in North America had sent Silas Deane of Groton to Paris as an agent to negotiate support from the French sovereign, but Paris acted cautiously at first.

Lafayette — a young aristocratic freemason and liberal with a head full of Enlightenment ideas — escaped to America in secret and was commissioned a major-general on George Washington’s staff in the last of his teenage years.

Given his relative youth, Lafayette inevitably turned out to be the final survivor of the generals of the Continental Army, and his 1824 trip to the United States solidified his popularity. He visited each of the twenty-four states in the Union at the time, including New York where the predecessor of the Seventh Regiment named itself the National Guards in honour of the Garde nationale Lafayette commanded in France.

This was the first instance of an American militia unit taking the name National Guard, which in 1903 was extended to all of state militia units which could be called upon for federal service.

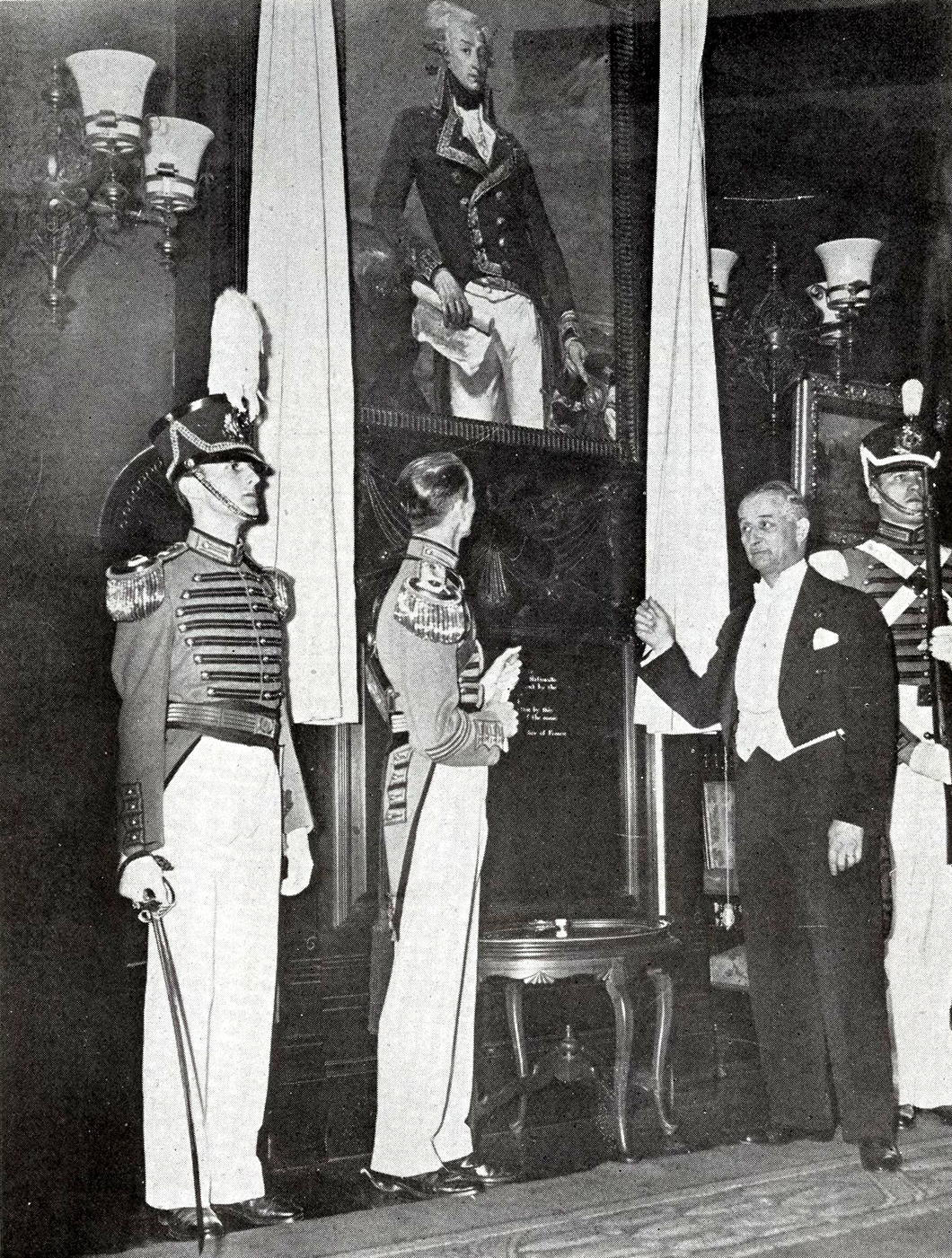

In honour of this connection and on the centenary of Lafayette’s 1834 death, the French Republic presented the Seventh Regiment with a copy of Joseph-Désiré Court’s portrait of the general that hangs in the 1792 Room of the Palace of Versailles. The Seventh set this in the wall of the Colonel’s Reception Room in their Armory, facing a copy of Peale’s portrait of General Washington.

The privilege of unveiling the portrait went to André Lefebvre de Laboulaye, the French Ambassador to the United States, who was given the honour of a full dress review of the Seventh Regiment on Friday 12 April 1935 before a crowd of three thousand in the Amory’s expansive massive drill hall.

Also present at the occasion was his son François, who eventually in 1977 stepped into his late father’s former role as French Ambassador to the United States. His Beirut-born grandson Stanislas served as French Ambassador to Russia 2006-2008 before being appointed to the Holy See until 2012. In April 2019, Stanislas de Laboulaye was put in charge of raising funds for the rebuilding of Notre-Dame following the fire that devastated the cathedral.

Harlem Reformed Dutch Church

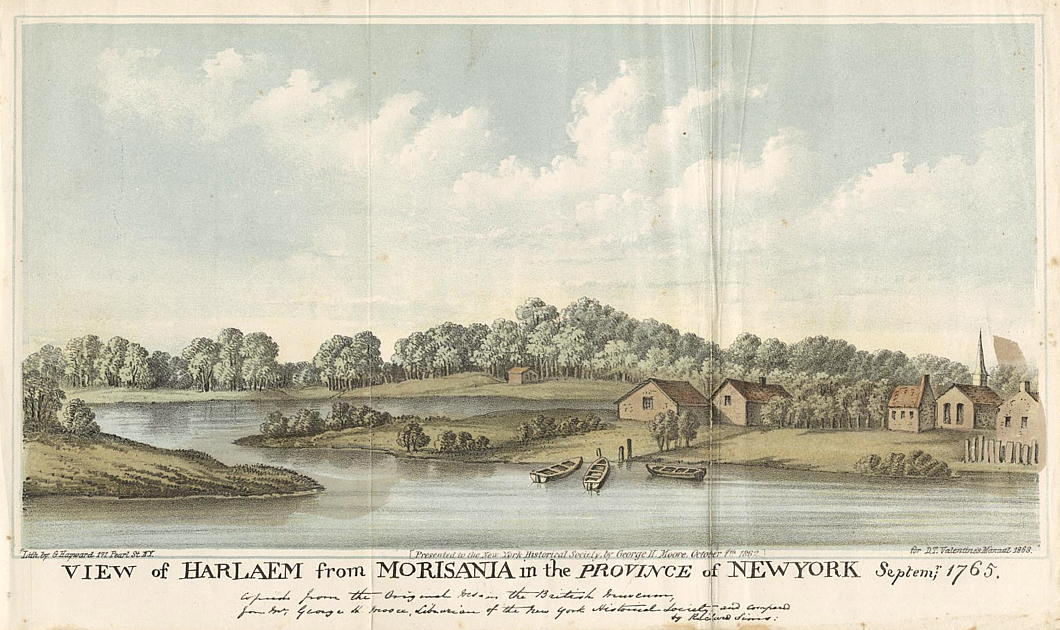

For much of Manhattan’s early colonial history, the island was home to two primary settlements: the port of New Amsterdam (later, from 1664, New York) way down at the southern tip and the town of Harlem up where the East River meets the Harlem River.

Christened after the Dutch city, Harlem is one of Manhattan’s most visible links to the Netherlands. The local newspaper is even called the New York Amsterdam News, once a prominent voice in Black America given this neighbourhood became predominantly African-American in the early twentieth century, and Amsterdam Avenue runs up as the spine of West Harlem.

Harlem was founded in 1658, thirty-four years after New Amsterdam was founded and thirty-two since Peter Minuit bought the whole island of Mannahatta off the Indians for sixty guilders.

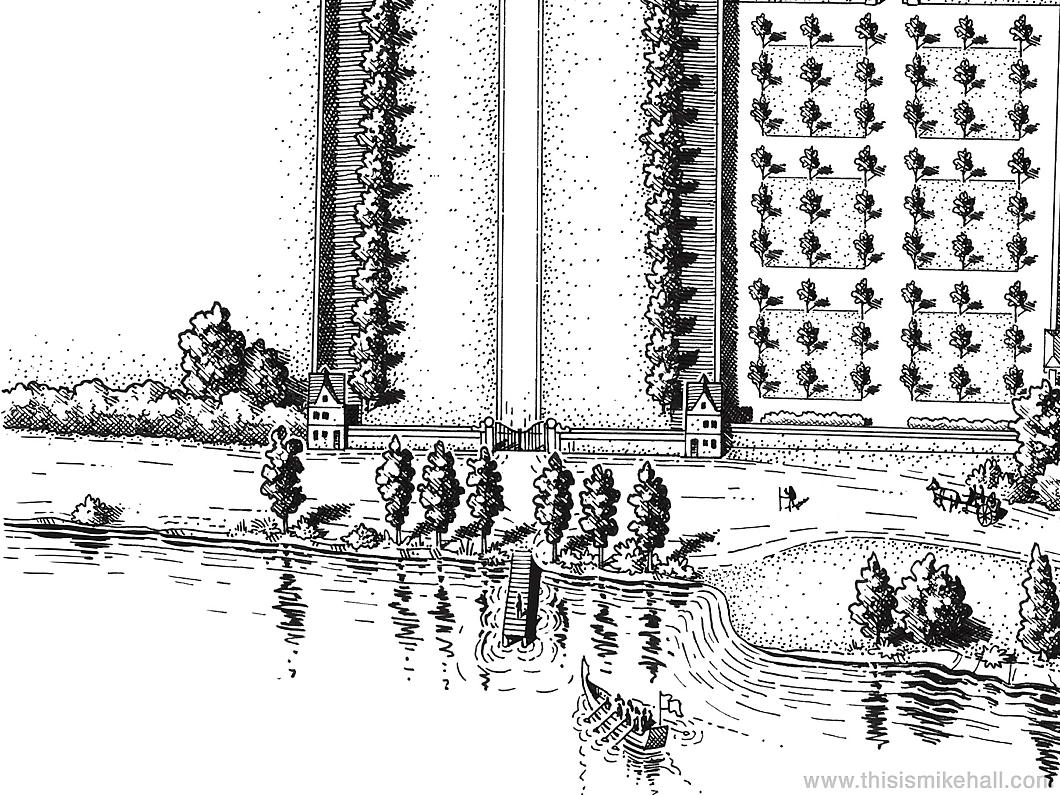

The town’s first church was founded in 1660 but didn’t have its own dedicated building for a few years. The Harlem Reformed Dutch Church, or Collegiate Church of Harlem, was built in 1665-67 right on the banks of the Harlem River, around the site of East 127th Street and First Avenue today.

Both the building and site was abandoned twenty years later when the congregation moved to its second building, completed 1687, just a little bit further south — near where East 125th meets First Avenue, or where the entrance ramp to the Triborough Bridge meets 125th.

It is this second building, which is depicted in the view above of Harlem village from Morissania across the river in the Bronx in 1765 (below).

The Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre

Níall McLaughlin Architects at Worcester College, Oxford

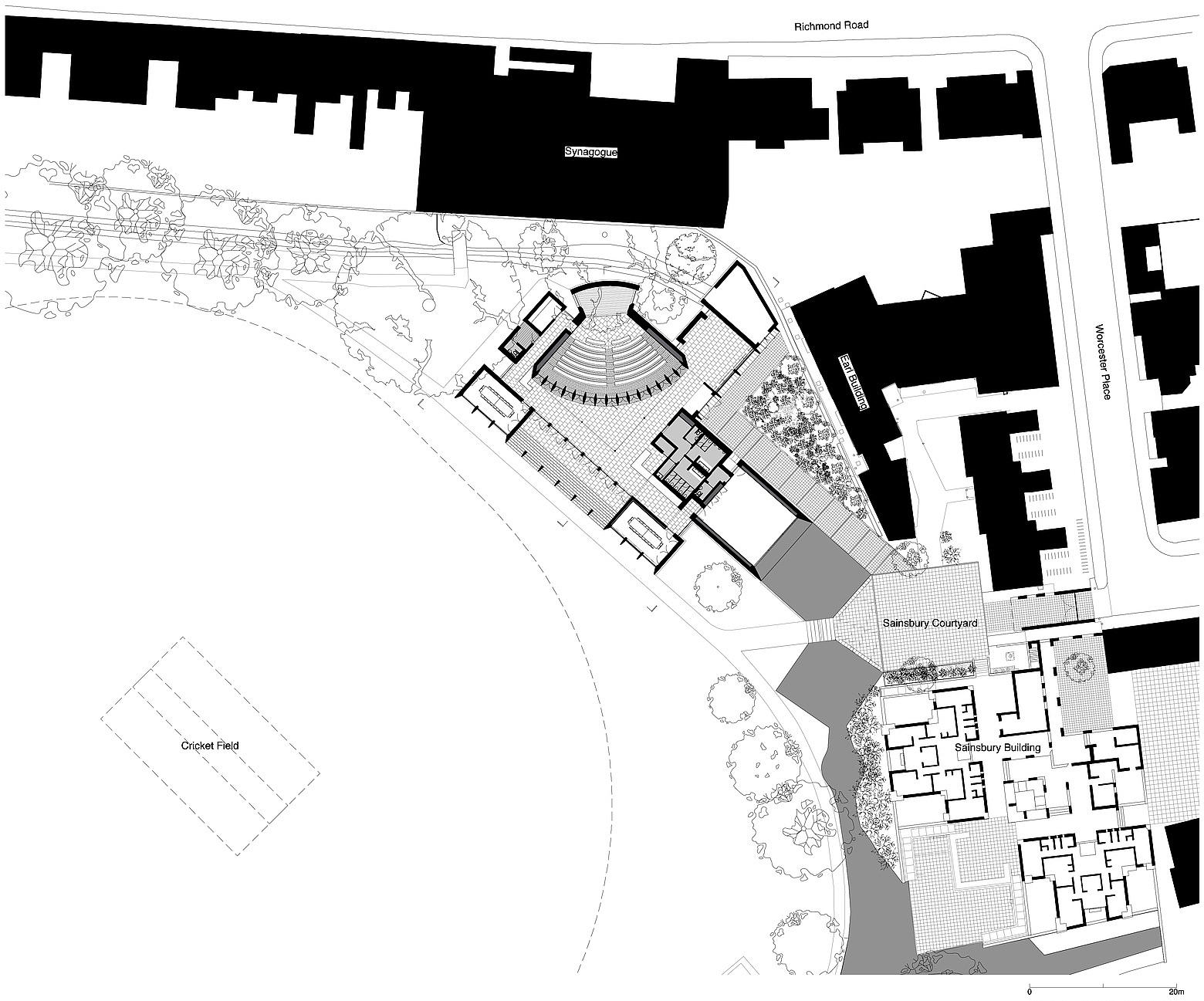

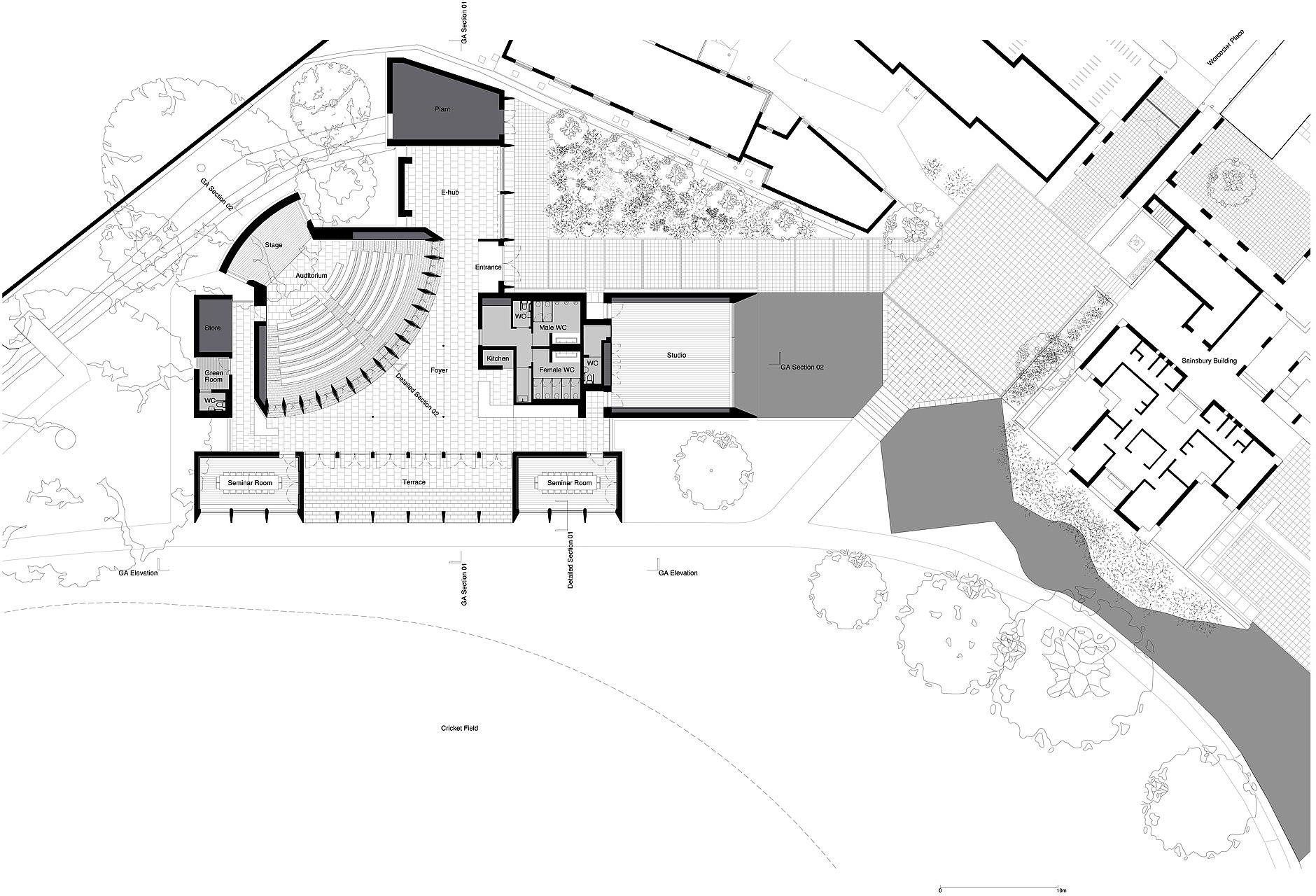

WORCESTER is one of the most spacious and scenic of Oxford’s colleges. The classical symmetry of its entrance terminates the view down the gentle curve of Beaumont Street from the Ashmolean Museum. The twenty-six acres of its grounds are pastoral, with lake, gardens, and the broad expanse of a cricket pitch.

Craftily inserted into this arcadia is the Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre designed by Níall McLaughlin Architects. Collegiate work is familiar to this firm, whose new library at Magdalene College, Cambridge, has won them this year’s Stirling Prize, and the Shah Centre provides new useful facilities for the college without giving it the middle finger.

It is named in gratitude to the generosity of an old boy of the college, HRH Nazrin Ali Shah of Perak, who delights in the title of Sultan, Sovereign Ruler, and Head of the Government of Perak, the Abode of Grace, and its dependencies. Judging by the outcome — itself shortlisted for a Stirling Prize in 2018 — I think he spent his money well.

Tempting though it might be to have a gentle wander through the grounds of the college first, the Shah Centre is best approached through the humble entrance lodge nestled in the corner of the L-shaped Worcester Place north of the college.

You are led to a little piazza — the Sainsbury Courtyard — framed by a pair of just-below-foot-level diamond-shaped shallow ponds of Kahn-ian geometry. (They are actually a tiny extension of the college lake.) The broad expanse of cricket pitch beyond, connected by a flat wooden bridge segmenting the two diamond ponds, is alluring. But off at a 45-degree-angle on the right, the entrance to the Shah Centre bids the visitor on.

Beyond the limestone cladding you move indoors to a sea of light-treated oak, in the thin supporting columns of the one-storey entrance hall curving around the arc of the lecture theatre and in the trelliswork ceiling.

To the left, the dance studio looks out onto the pools through three giant panes of floor-to-ceiling glass.

To the right, a small bar can double as a registration desk.

The lecture theatre seats 170 and is accessed through a curve of wooden slats that hide panels that can swing out if closing the space is necessary.

Auditoria with ceilings sloping down toward the stage usually feel cramped but here the ceiling is arranged in sharp corrugations (like the flanges of the Gonbad-e Qabus) which capture the light from the clerestory behind.

The feeling is one of spaciousness: rather than facing downwards they are like rays of the sun reaching outwards and up. Instead of wings offstage, there are tall windows of a single sheet of glass flanking, offering natural side light.

The view from the stage is even better, looking out at the gentle curve of clear windows breaking at near-half-way, dividing the anterior spaces below from the open skies above.

Straight out from the auditorium is the terrace with its steps flowing gently down to the field beyond.

It is from the cricket ground that we get the best view of the Shah Centre. The lines are elegant, and there’s a hint of the better architects from Italy’s fascist era — Pagano or Terragni, not Piacentini. The easy movement of space and light, with a gentle breeze rolling off the green.

The architectural genius of the Oxford college as a type is that it allows for the magnificent to be completed on a humane scale for an intimate community of students, scholars, and academics. Níall McLoughlin’s skill at achieving this in a modern idiom is what makes the accolades he accrues — fickle gifts at the best of times — so justified in his case.

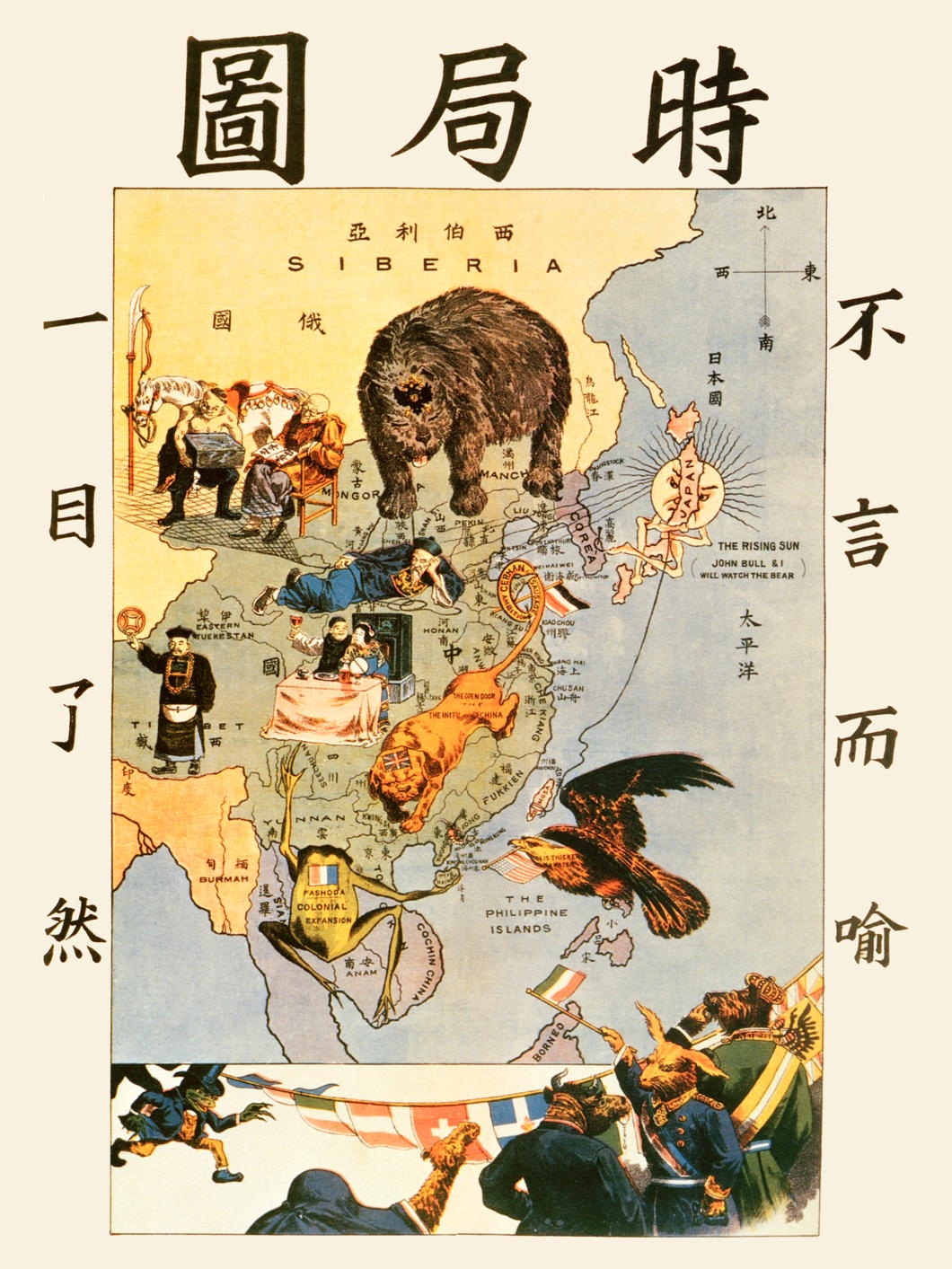

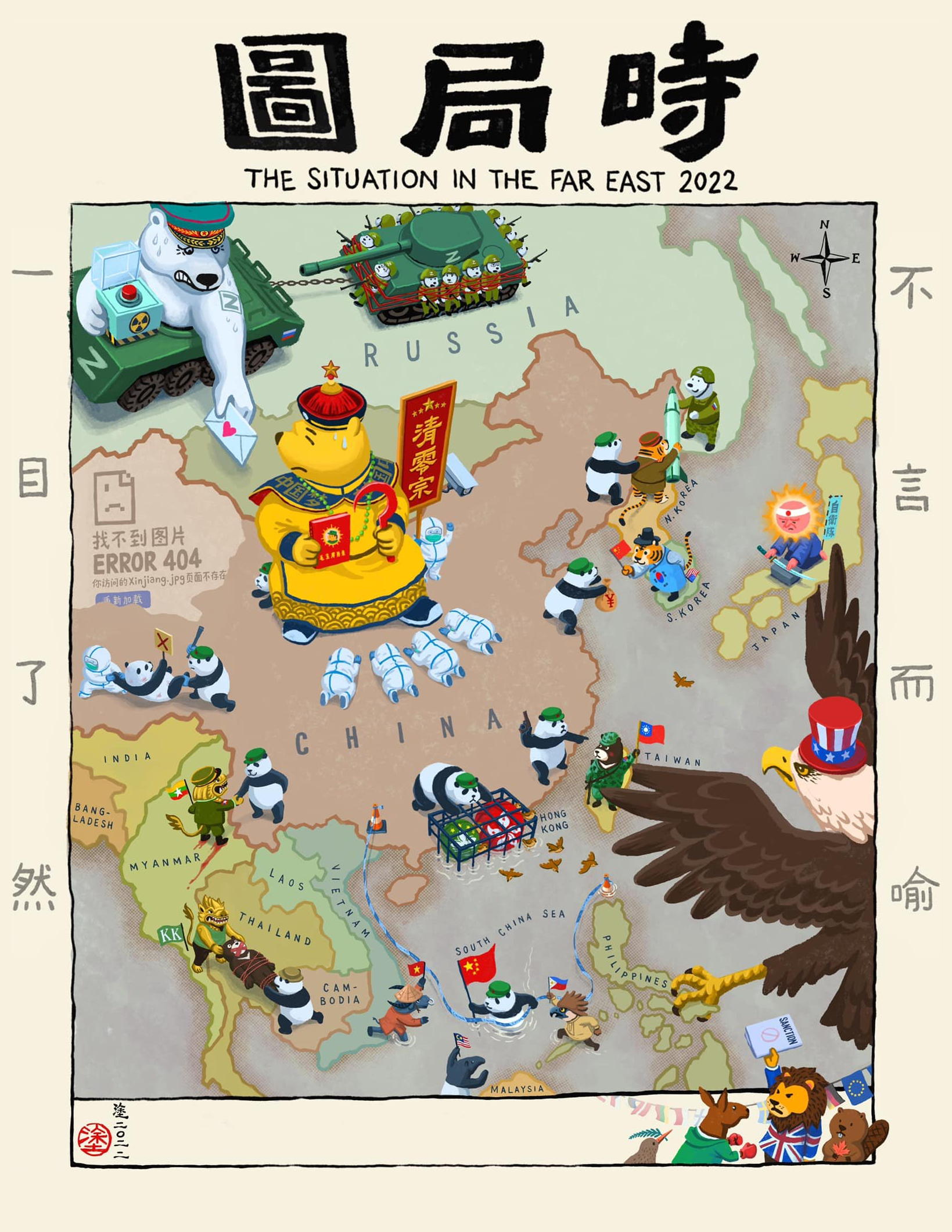

The Situation in the Far East

A century-old geopolitical cartoon is updated for today

Tse Tsan-tai — or 謝纘泰 if you fancy — was by any standard a remarkable man. Born in New South Wales, this Chinese-Australian Christian was a colonial bureaucrat, nationalist revolutionary, constitutional monarchist, pioneer of airship theory, and co-founded the South China Morning Post — still one of the most prominent newspapers in the Orient.

Tse’s most important visual contribution was a widely distributed political cartoon usually known in English as ‘The Situation in the Far East’ or in Chinese as the ‘Picture of Current Times’ (below).

Crafted as a propaganda measure to warn his fellow Chinese of the designs of foreign powers, the cartoon depicts the perils facing the Middle Kingdom.

Japan, with its expanding navy, proclaims it will watch the seas with its ally, Great Britain. The Russian bear looms from Siberia, crossing the border into China. A British lion sprawls over the land, its tail tied up by the “German Sausage Ambitions” at Tsingtao. The French frog guards Indochina while the American eagle lurks from the Philippines.

Meanwhile, the Chinese figures show sleeping bureaucrats and carousing intelligentsia unresponsive to the external threats.

Now the exiled Hong Kong artist Ah To (阿塗) has updated ‘Situation’ to reflect the realities of 2022. (more…)

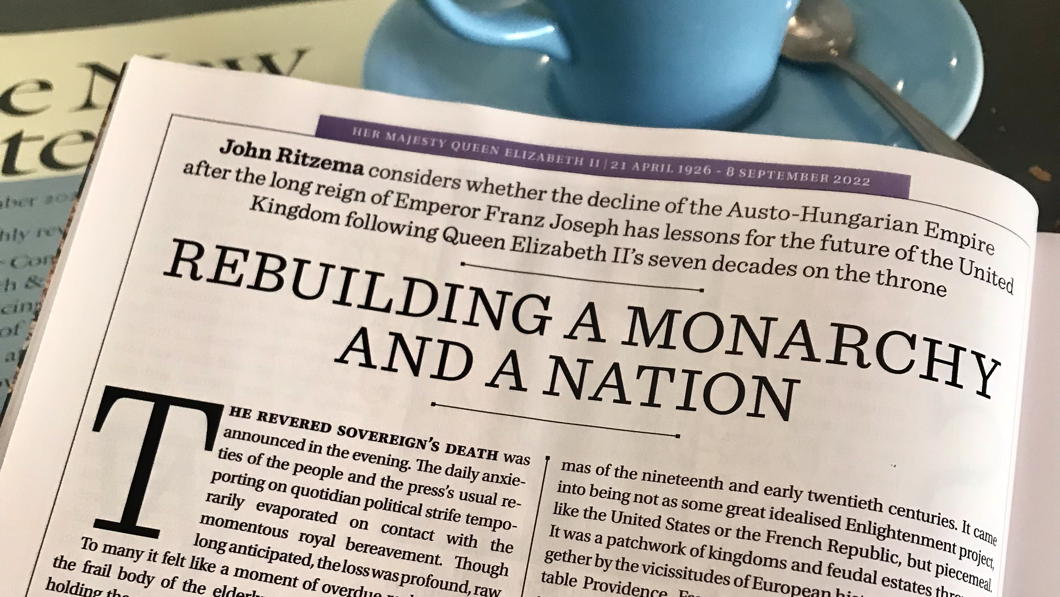

The death of The Monarch

The revered Sovereign’s death was announced in the evening. The daily anxieties of the people and the press’s usual reporting on quotidian political strife temporarily evaporated on contact with the momentous royal bereavement. Though long anticipated, the loss was profound, raw.

To many it felt like a moment of overdue reckoning. As if the frail body of the elderly monarch had somehow been holding the great, ancient, long-weakening and precariously multinational state together. The world of the previous century had finally, almost imperceptibly, slipped away. Franz Joseph was dead. …

In the October 2022 number of The Critic, Dr John Ritzema explores the parallels between the recent demise of our late sovereign with the death of the Emperor Franz Joseph over a hundred years earlier — and wonders whether there are any lessons for the reign of King Charles III: Rebuilding a Monarchy and a Nation.

One of those minor curiosities that both Franz Joseph and Elizabeth II were succeeded by Charleses — the latter by her son, and the former by his grand-nephew Blessed Charles of Austria.

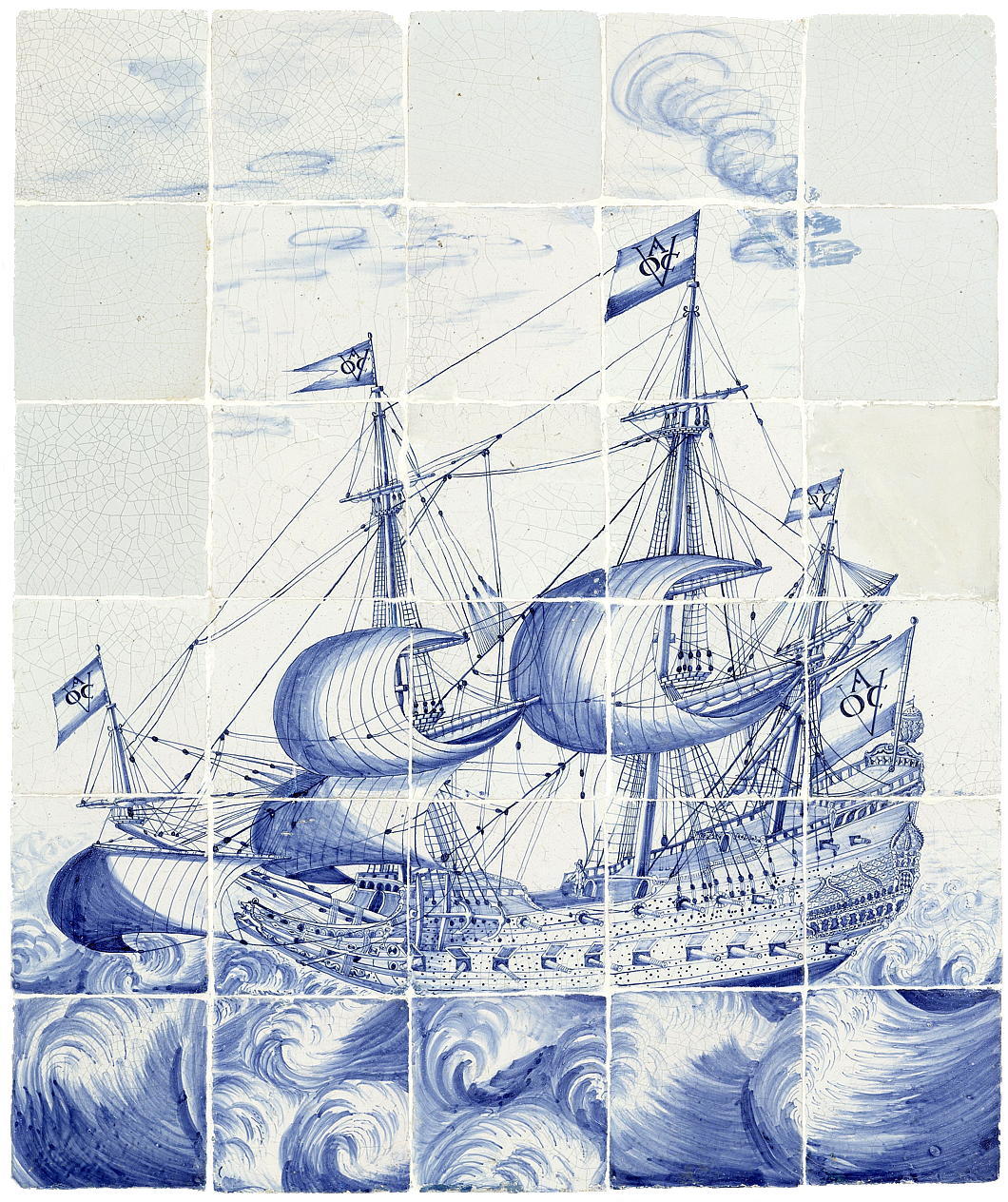

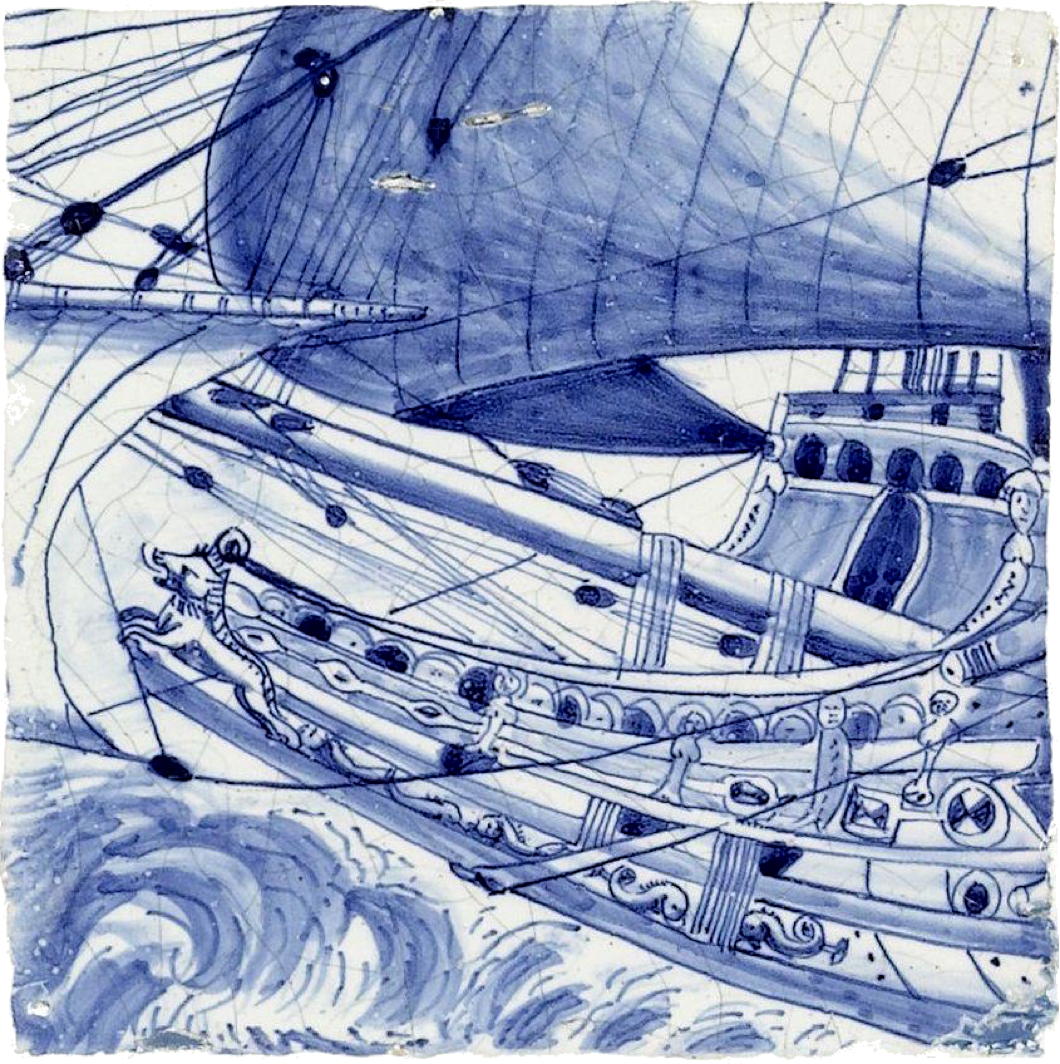

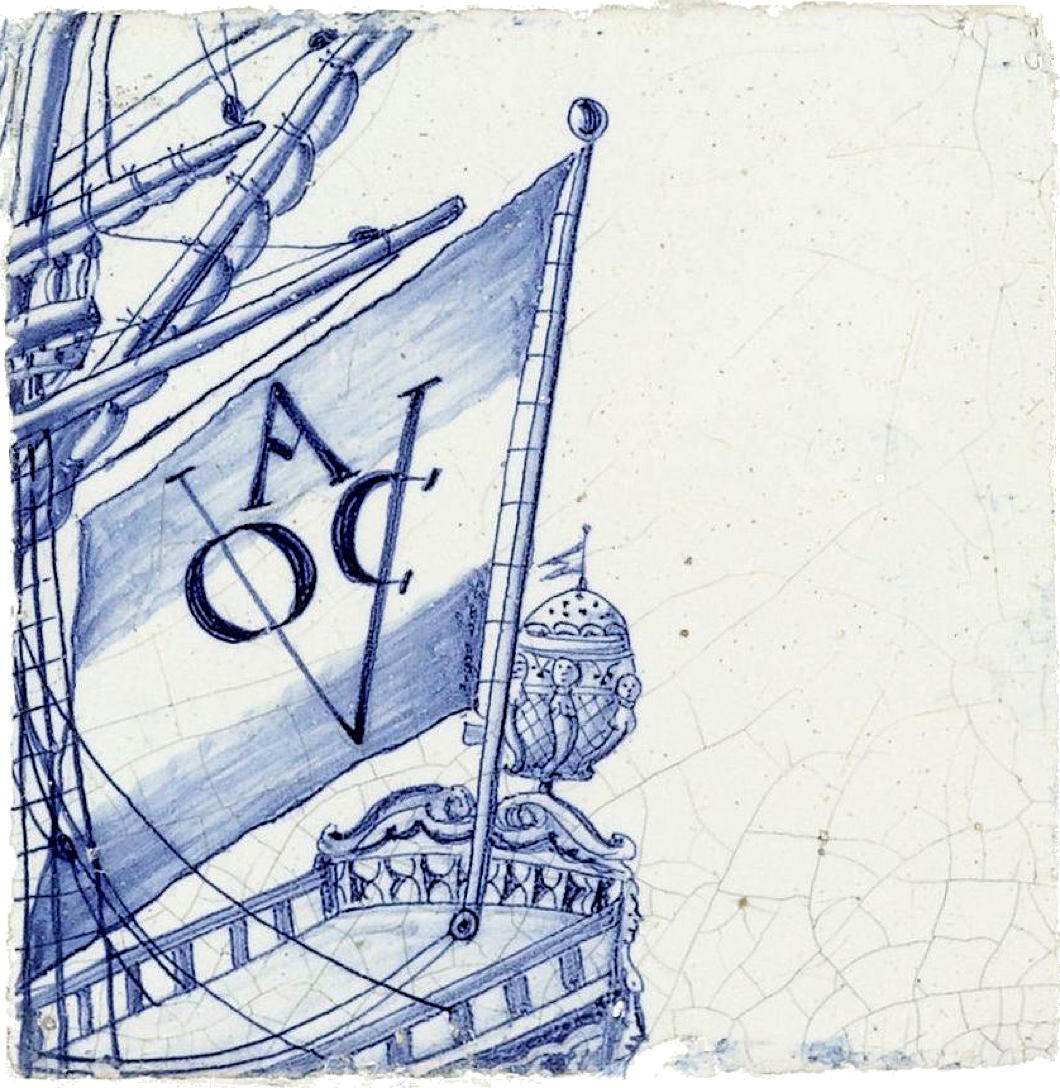

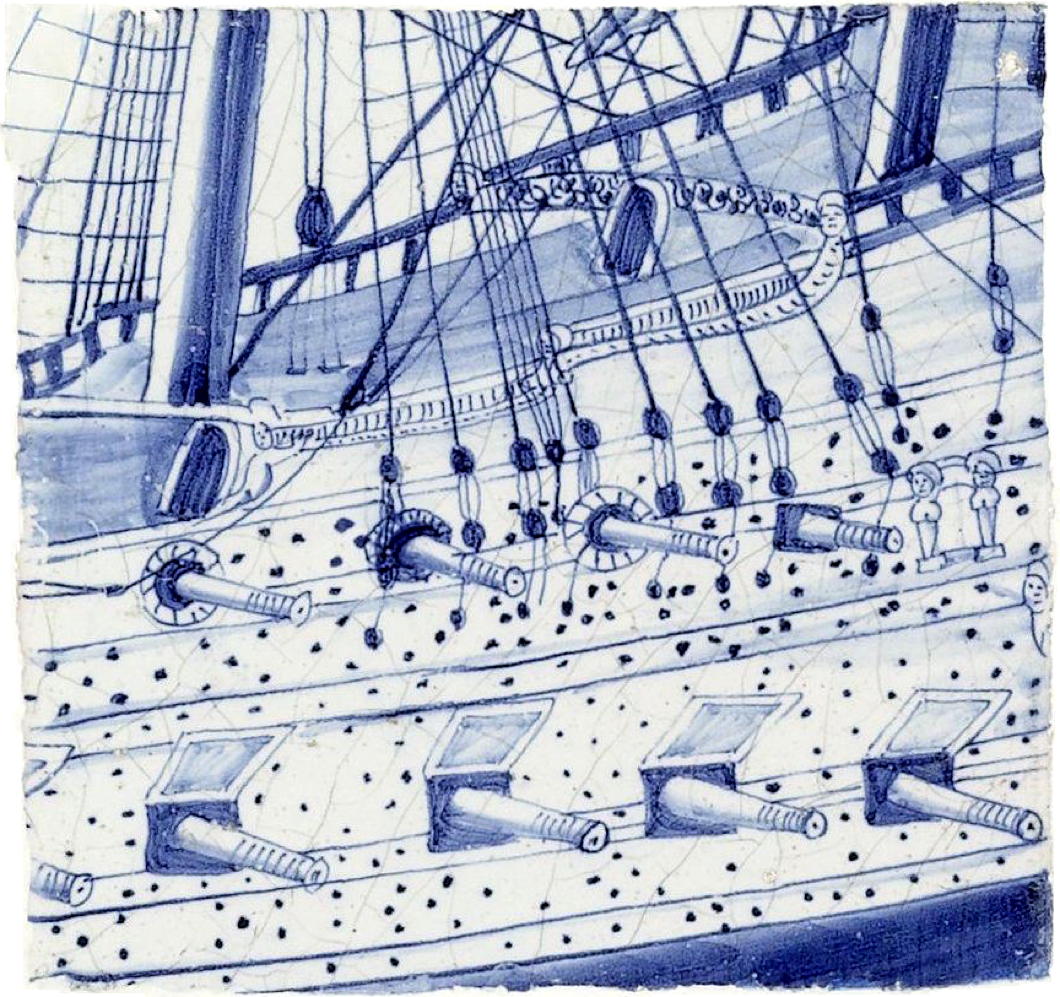

An East Indiaman

English sea-goers and merchants commonly referred to any ship of the Dutch VOC (or of other similar companies) as an ‘East Indiaman’.

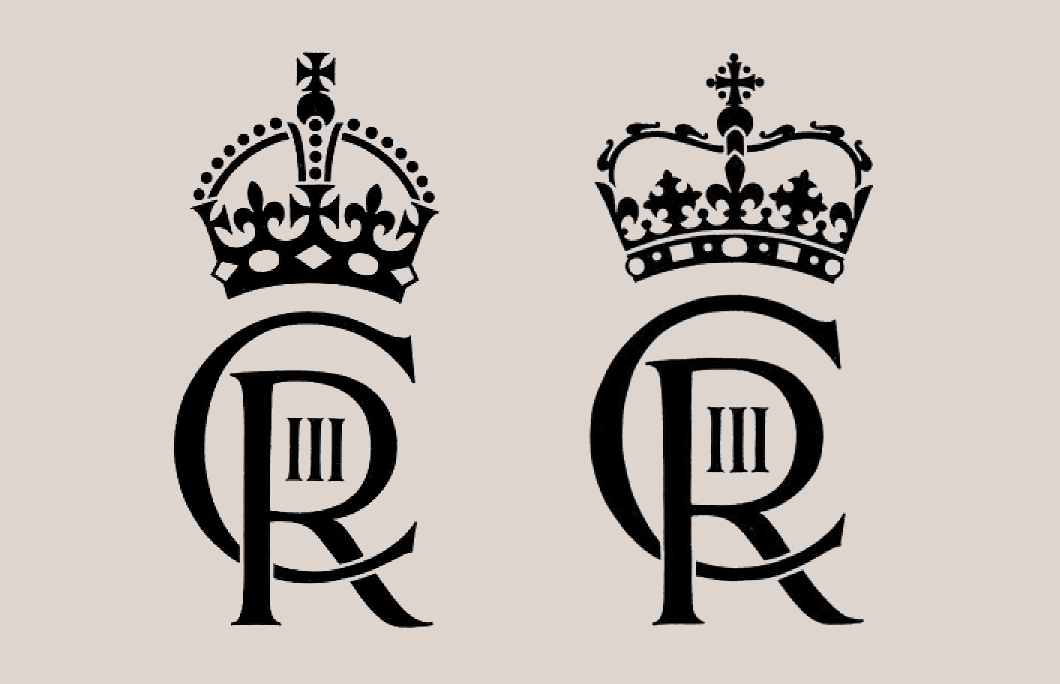

Cypher Shift

Out with the old, in with the new: the King has released his new royal cypher, with a stylised CR III replacing the familiar EIIR. As with so many things, I am sure we will get used to it with time.

Given the longevity of the late Queen’s reign it will be some time before we see it appearing on pillarboxes, but it will enter our lives more quickly via postal franking, stamps, currency, and uniforms.

Many are trying to come up with complex, almost mystical, explanations for why St Edward’s Crown has been replaced with the Tudor crown atop the cypher. More likely, I suspect, is that it is a useful means of giving the new reign a respectful visual differentiation from its preceding one.

I’ve always been rather fond of the Tudor crown, and the Caledonian version of the new cypher rightly includes the Crown of Scotland — the oldest amidst the Crown Jewels of this realm as (unlike England) Scotland was spared the iconoclastic destruction of Cromwell’s republic.

The new royal cypher, left, and its Scottish variant, right.

Bonnington Square

This little enclave is one of the best-kept secrets of London. I used to live just around the corner from Bonnington Square and walking into it was like entering a secret world.

Just steps from the gritty urban world of the Vauxhall gyratory there is a verdant realm where a good coffee can be had and where many neighbours actually know eachothers’ names.

Built to house railway workers, the whole square was compulsorily purchased by that archetype of grim 1970s misery, the Inner London Education Authority, to be demolished as a sports ground for the neighbouring school.

Within a decade, however, no demolition had been approved and the squatters had moved in — in this case organising a cooperative, building a community garden, and running a shop. They managed to negotiate the purchase of their homes from the Greater London Council and Bonnington Square was saved.

Gardeners have turned its streets into one of the most lushly verdant corners of central London, and now this five-bedroom house is up for grabs. If you have £1.9 mil going spare it would be a nice place to live.

For an ardent sun-lover like me the roof terrace — with barbecue artfully inserted into the old chimney breast — is the best feature, along with the proximity to the excellent Italo Deli.

L’Élysée à la plage

The Fort de Brégançon: Riviera Retreat of France’s Presidents

When France’s head of state needs to let his hair down every summer, the Republic has a convenient presidential residence just for him to do so: the Fort de Brégançon on the Côte d’Azur.

There has been a fortress here since at least mediæval times, and Gen. Buonaparte (later emperor) ordered its ramparts renewed after the retaking of Toulon in 1793. It continued to serve military purposes until 1919, but in 1924 it was leased out to a local mercantile family, the Tagnards.

They passed their lease on to the former government minister Robert Bellanger, who improved the island greatly, connecting it to the water and electricity supply, building the causeway linking it to the mainland, and laying out the Mediterranean garden. Bellanger’s leased expired in 1963 and Brégançon returned to the property of the state.

President de Gaulle stayed a night on the island in 1964 but found the bed too small and the mosquitos too bothersome. Nonetheless, his wartime comrade René-Georges Laurin (mayor of Saint-Raphaël up the coast) convinced him it would make a suitable summer residence that befitted the dignity of France’s head of state.

The architect Pierre-Jean Guth was seconded over from the Navy to adapt and update the fort to this end. The rooms are a little small, but their cozy intimacy adds to the fort’s informality. The presidential bedroom features a Provençal bed facing the sea with a view towards the nearby island of Porquerolles.

Pompidou and Giscard enjoyed the island but Mitterand mostly neglected the island except when welcoming Chancellor Kohl and Taoiseach Garrett Fitzgerald. Chirac and his wife took up Brégançon and were often seen by the locals on their way to Mass.

Sarkozy liked to be photographed on his jogs from the island but after he abandoned his wife and took up with his mistress he preferred holidaying at Carla Bruni’s far grander and more comfortable summer residence.

Hollande opened the fort up to public visitors, hoping to recoup some of the costs of maintaining the property. Macron has taken to the island frequently for his summers, for meetings with foreign leaders, and for working weekends with his ministers.

With summer fires raging, a minority in parliament, and myriad other problems brewing, no doubt Macron has much on his agenda.

All the same, for France’s sake, we can’t help but hope Monsieur le Président has a happy holiday. (more…)

Monolingual Limitations

I’m  sure I wasn’t the only twelve-year-old whose favourite book was Edward Luttwak’s delicious Coup d’État: A Practical Handbook — an excellent gift from my father. The work gave me a lifelong fascination with the golpe de Estado, a phenomenon of government all too increasingly a rare species in our post-Cold War era.

sure I wasn’t the only twelve-year-old whose favourite book was Edward Luttwak’s delicious Coup d’État: A Practical Handbook — an excellent gift from my father. The work gave me a lifelong fascination with the golpe de Estado, a phenomenon of government all too increasingly a rare species in our post-Cold War era.

Just about everything written or said by Luttwak — lately a cattle farmer in Paraguay — is worth reading or listening to. For a start you could read his contributions to the LRB or to the excellent American Jewish Tablet magazine.

I have been waiting for someone to offer a refutation of his provocative Prospect essay on how the Middle East is less relevant than ever, and it would be better for everyone if the rest of the world learned to ignore it.

David Samuels chat with Luttwak this month on the subject of the Three Blind Kings — Putin, Biden, and Xi — offers some superb insights as well as amusements.

Among the lessons that Luttwak is keen to drive home — and he says so over and over and over again on Twitter — is that American intelligence-gathering (and government in general) is too reliant on technology with too few officials, analysts, and operatives actually learning the language of those they are attempting to surveil.

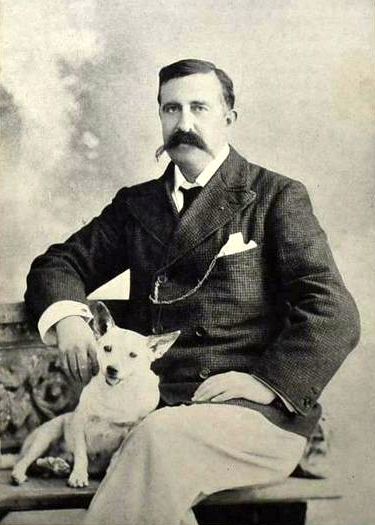

That this state of monolingual limitation was not always the case was driven home in an excellent piece by Jonathan Gaisman in the February 2022 New Criterion concerning Sir Ronald Storrs (left, 1881–1955) — “the most brilliant Englishman in the Near East” as Lawrence of Arabia called him.

That this state of monolingual limitation was not always the case was driven home in an excellent piece by Jonathan Gaisman in the February 2022 New Criterion concerning Sir Ronald Storrs (left, 1881–1955) — “the most brilliant Englishman in the Near East” as Lawrence of Arabia called him.

An accomplished Arabist, Storrs served as Oriental Secretary for the British administration in Egypt before going on to become Military Governor of Jerusalem, Governor of Cyprus, and Governor of Northern Rhodesia, from which role he retired on health grounds, returned to the metropole, and served a few years on London County Council.

Gaisman relays this delicious anecdote from the British official’s 1937 autobiography Orientations:

Sometime in 1906 I was walking in the heat of the day through the Bazaars. As I passed an Arab café an idle wit, in no hostility to my straw hat but desiring to shine before his friends, called out in Arabic, “God curse your father, O Englishman.”

I was young then and quicker-tempered, and foolishly could not refrain from answering in his own language that I would also curse his father if he were in a position to inform me which of his mother’s two and ninety admirers his father had been.

I heard footsteps behind me and slightly picked up the pace, angry with myself for committing the sin [of] a row with Egyptians. In a few seconds I felt a hand on each arm. “My brother,” said the original humorist, “return, I pray you, and drink with us coffee and smoke. I did not think that Your Worship knew Arabic, still less the correct Arabic abuse, and we would fain benefit further by your important thoughts.”

Gaisman further spoils us with another excellent story — this time about Storrs’ predecessor as Oriental Secretary in Cairo, Mr Harry Boyle:

[Boyle] was taking his tea one day on the terrace of Shepheard’s Hotel when he heard himself accosted by a total stranger: “Sir, are you the Hotel pimp?”

“I am, Sir,” Boyle replied without hesitation or emotion, “but the management, as you may observe, are good enough to allow me the hour of five to six as a tea interval. If, however, you are pressed perhaps you will address yourself to that gentleman,” and he indicated [the self-made tea magnate] Sir Thomas Lipton, “who is taking my duty; you will find him most willing to accommodate you in any little commissions of a confidential character which you may see fit to entrust to him.”

Boyle then paid his bill, and stepped into a cab unobtrusively, but not too quickly to hear the sound of a fracas, the impact of a fist and the thud of a ponderous body on the marble floor.

Boyle’s 1937 obituary in the Palestine Post noted he was “a gifted linguist, speaking no fewer than twelve languages”. When Lord Cromer was Britain’s proconsul in Egypt, he and Boyle were such frequent perambulators along the Nile that Boyle earned the nickname Enoch, for he “walked daily with the Lord”.

Boyle’s 1937 obituary in the Palestine Post noted he was “a gifted linguist, speaking no fewer than twelve languages”. When Lord Cromer was Britain’s proconsul in Egypt, he and Boyle were such frequent perambulators along the Nile that Boyle earned the nickname Enoch, for he “walked daily with the Lord”.

During these walks, Cromer was keen to mix with Egyptians of the most humble backgrounds and was aided by Boyle’s linguistic skills. Such was his excellence in Arabic that, returning to Egypt many years later, Boyle was recognised by a peasant farmer many miles outside of Cairo and warmly embraced as the man who used to walk the Nile with the British lord.

“In the hot and brooding nights of the Egyptian summer,” the Post appreciation also relates, “when all who were at liberty to do so had fled to cooler climes, Cromer and Harry Boyle might often have been seen seated after dinner on the veranda of the Agency in Cairo reading aloud alternately passages from the Iliad.”

Perhaps all is not lost. While I can’t speak for the state of the gift of tongues at Langley, at least the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom can launch into Homer, in Greek, from memory.

But Luttwak would surely be right to retort that it is among the mid-level officials and analysts that linguistic skills are most missing — nor are we currently threatened by Athens, Sparta, or Corinth.

30 mai 1968

The events of May 1968 have been fetishised by the romantic radical left but ended in the triumph of the popular democratic right. Battered by two world wars, France had enjoyed an unprecedented rise in living standards since 1945 — especially among the poorest and most hard-working — and a new generation untouched by the horrors of war and occupation had risen to adulthood (in age if not in maturity). The ranks of the middle class swelled as more and more people enjoyed the material benefits of an increasingly consumerised society, while those left behind shared the same aspirations of moving on up.

Like any decadent bourgeois cause, the spark of the May events was neither high principle nor addressing deep injustice but rather more base impulses: male university students at Nanterre were upset they were restricted from visiting female dormitories (and that female students were restricted from visiting theirs). The ensuing events involved utopian manifestos, barricades in the streets, workers taking over their factories, a day-long general strike and several longer walkouts across the country.

The French love nothing more than a good scrap, especially when it’s their fellow Frenchmen they’re fighting against. Working-class police beat up middle-class radicals but for much of the month both sides made sure to finish in time for participants on either side to make it home before the Métro shut for the evening. But workers’ strikes meant everyday life was being disrupted, not just the studies of university students. When concessions from Prime Minister Georges Pompidou failed to calm the situation there were fears that the far-left might attempt a violent overthrow of the state.

De Gaulle himself, having left most affairs in Pompidou’s hands, finally came down from his parnassian heights to take charge but then suddenly disappeared: the government was unaware of the head of state’s location for several tense hours.

It turned out the General had flown to the French army in Germany, ostensibly to seek reassurance that it would back the Fifth Republic if called upon to defend the constitution. De Gaulle is said to have greeted General Massu, commander of the French forces in West Germany, “So, Massu — still an asshole?” “Oui, mon général,” Massu replied. “Still an asshole, still a Gaullist.”

The morning of 30 May 1968, the unions led hundreds of thousands of workers through the streets of Paris chanting “Adieu, de Gaulle!” The police kept calm, but the capital was tense and there was a sense that things were getting out of hand. Pompidou convinced de Gaulle the Republic needed to assert itself.

Threatened by a radicalised minority, de Gaulle called upon the confidence of the ordinary people of France. At 4:30 he spoke on the radio briefly, announcing that he was calling for fresh elections to parliament and asserting he was staying put and that “the Republic will not abdicate”.

Before the General even spoke some his supporters (organised by the ever-capable Jacques Foccart) were already on the avenues but the short four-minute broadcast inspired teeming masses onto the streets of central Paris, marching down the Champs-Élysées in support of de Gaulle.

A Home for Bard and Ballet

Sir Basil Spence’s unbuilt Notting Hill theatre

Sir Basil Spence was just about the last (first? only?) British modernist who was any good. His British Embassy in Rome is hated by some but combines a baroque grandeur appropriate to the Eternal City with the crisp brutalism of modernity that makes it true to its time.

In 1963, Spence accepted the commission from the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Ballet Rambert for a London venue to host the performances of both bodies.

The poet, playwright, and theatre manager Ashley Dukes had died in 1959, leaving a site across Ladbroke Road from his tiny Mercury Theatre (in which his wife Marie Rambert’s ballet company performed) for the building of a new hall.

The design moves from the sweeping curve of the street frontage up to a series of angular concoctions and finally the large fly-space above the stage itself.

It made the most of a highly constricted site and would have housed 1,100-1,600 patrons (historical sources vary on this figure). This was a big step up from the old Mercury Theatre which housed 150 at a push.

Ultimately, the plan failed. London County Council was worried there wasn’t enough parking in the area, and the Royal Shakespeare Company was tempted away by the City of London Corporation which was building the Barbican Centre.

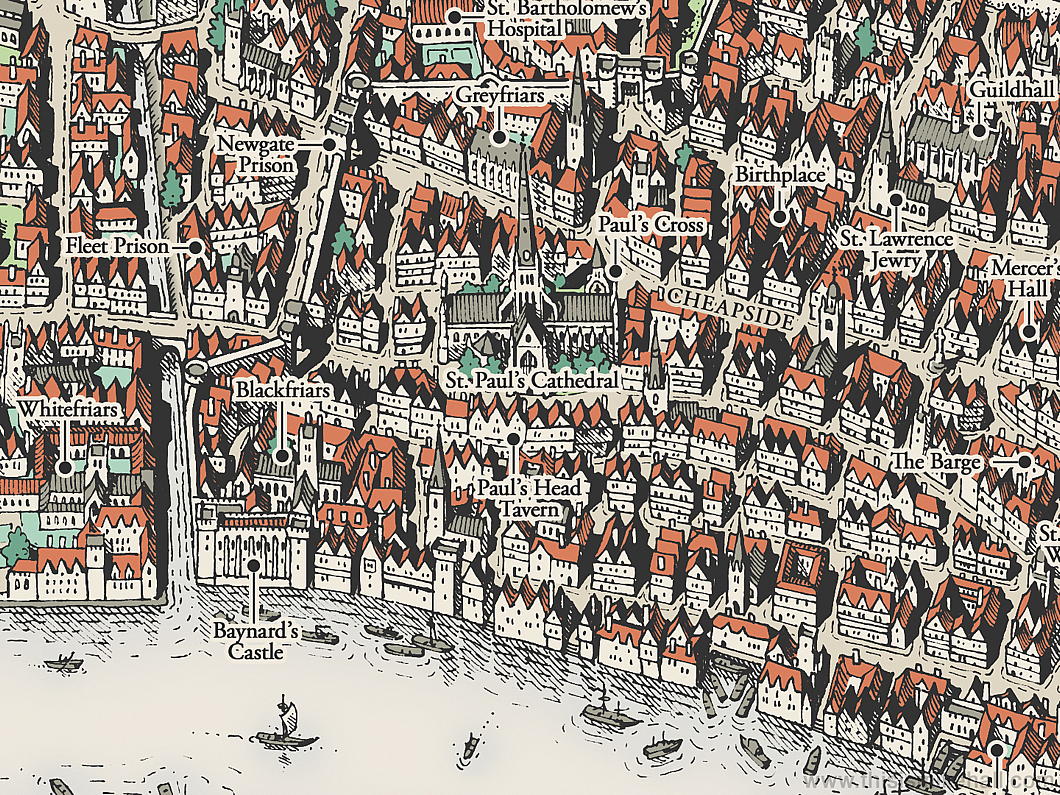

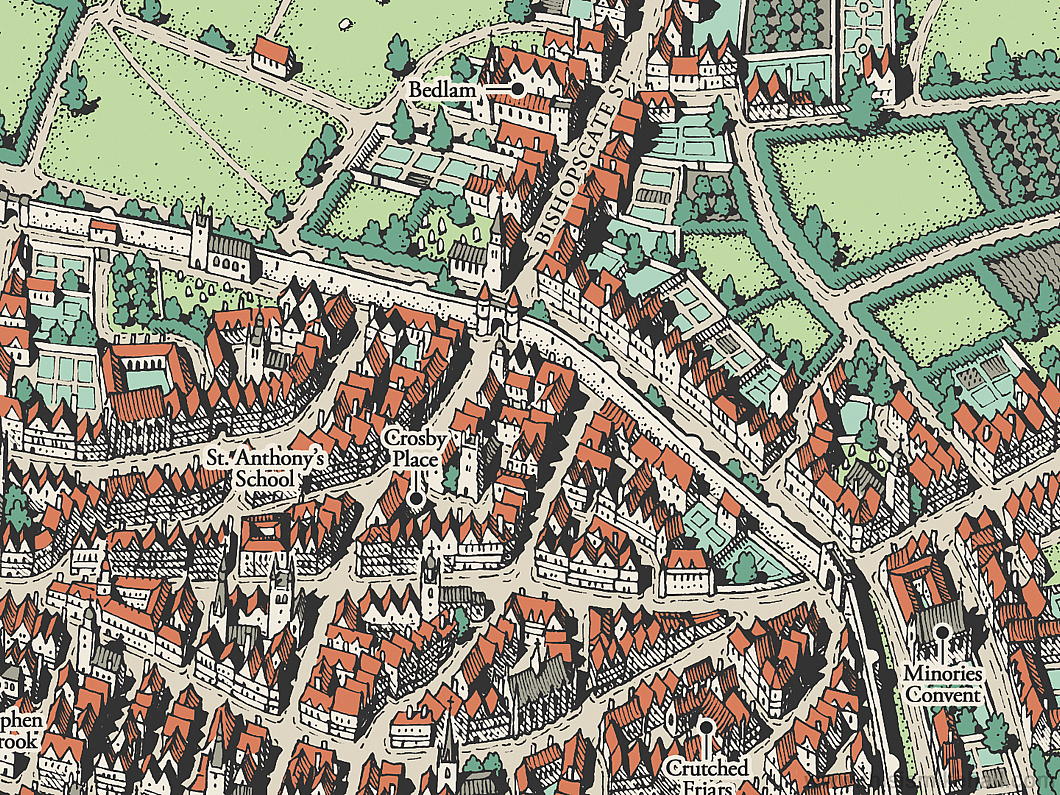

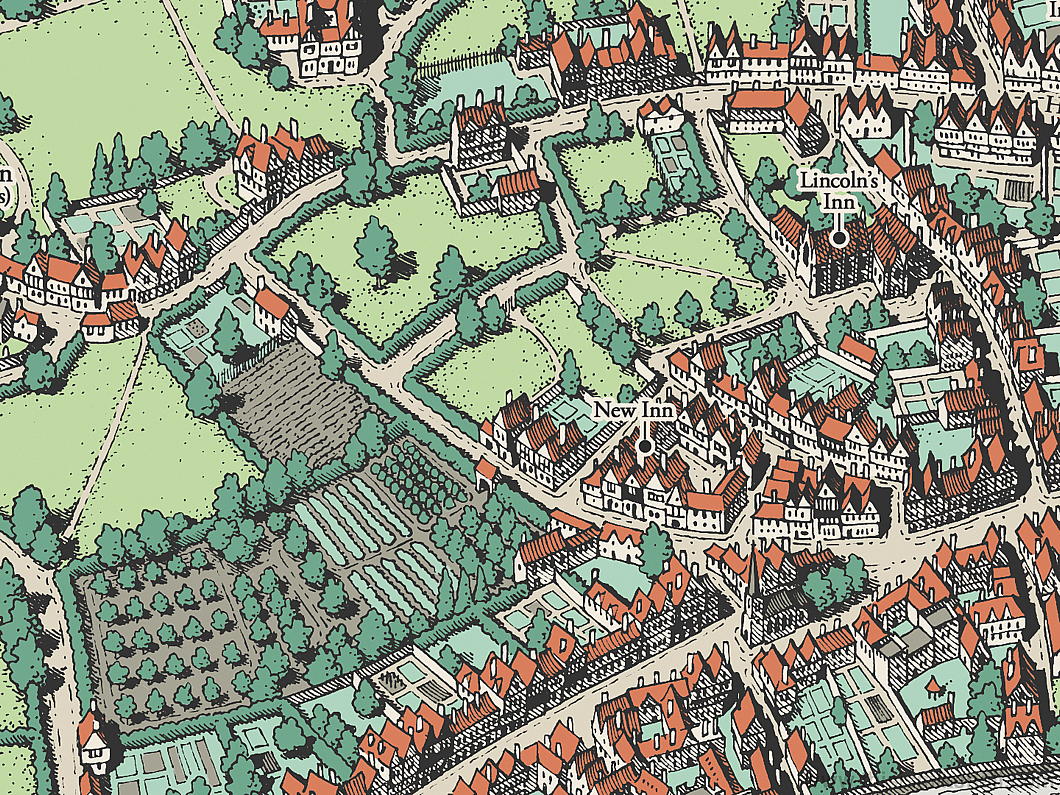

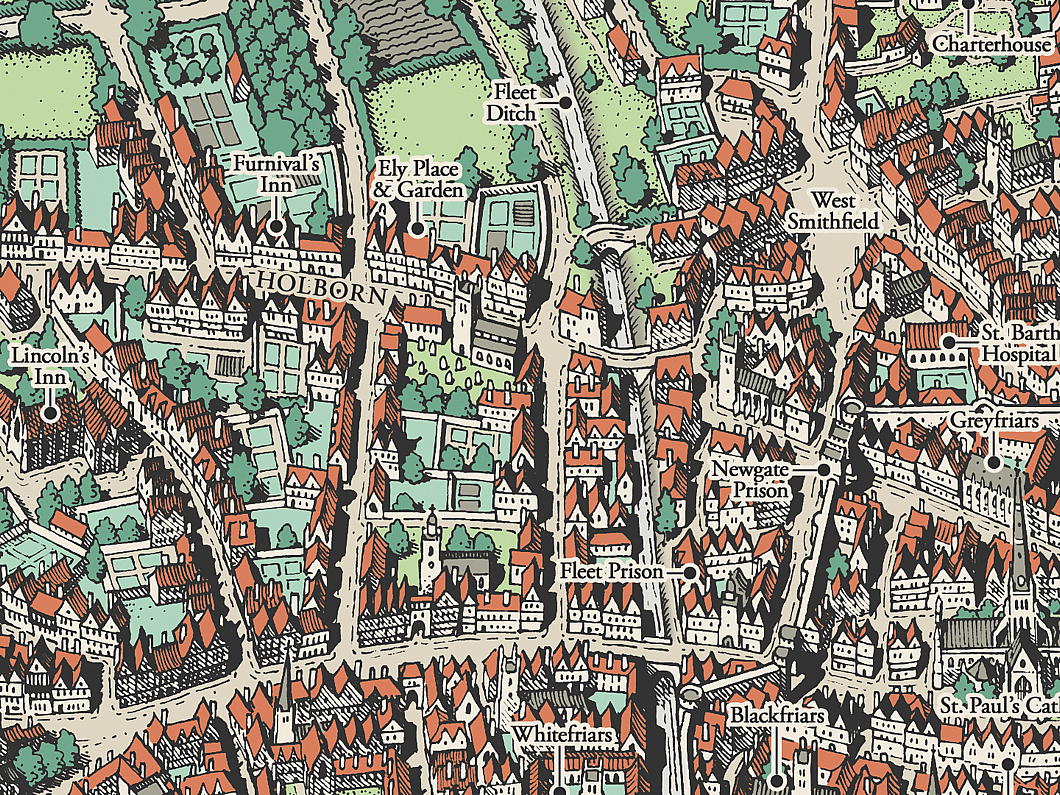

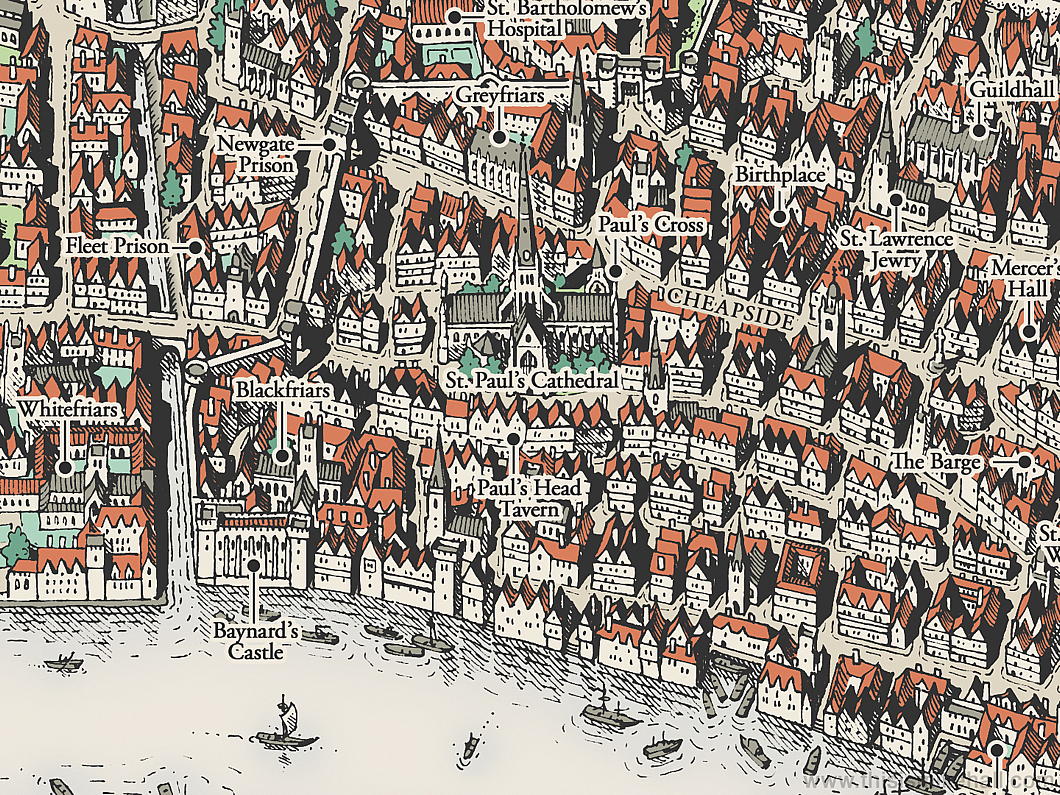

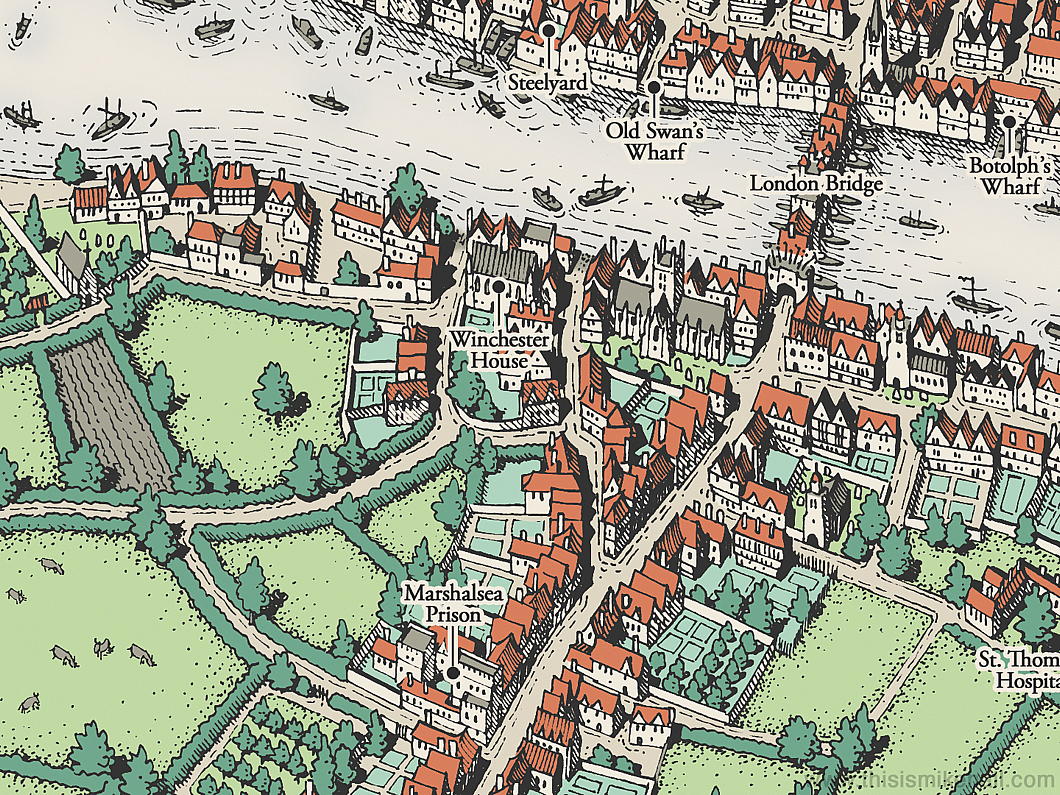

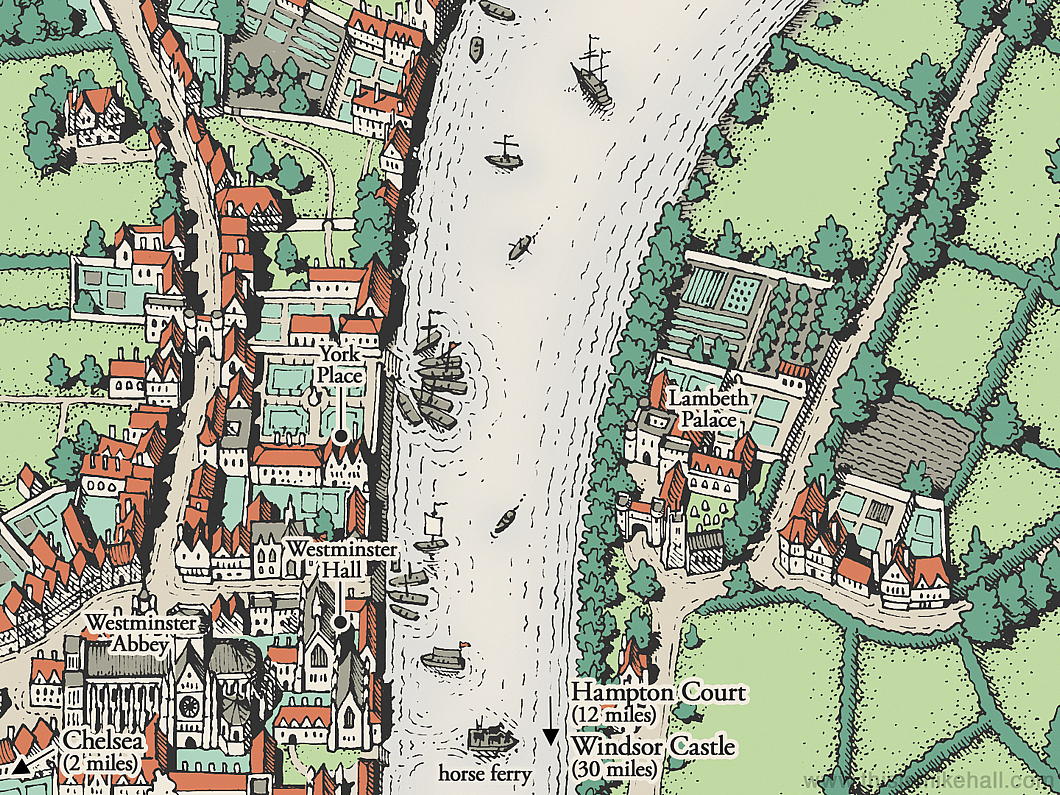

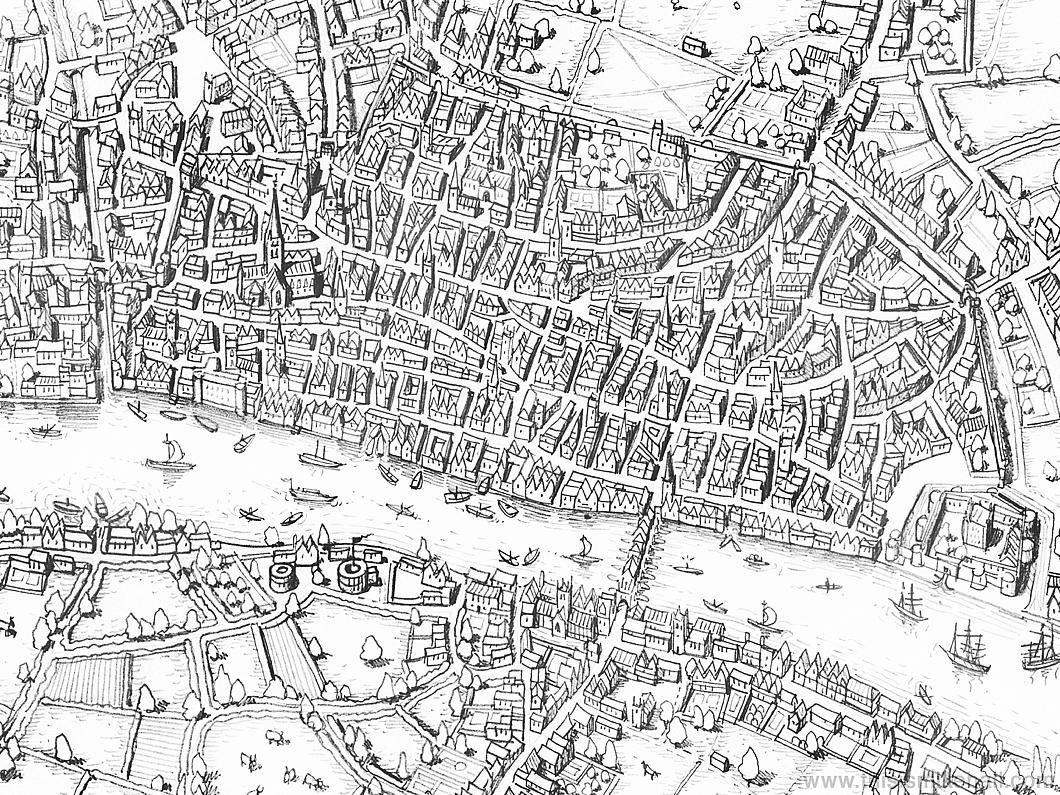

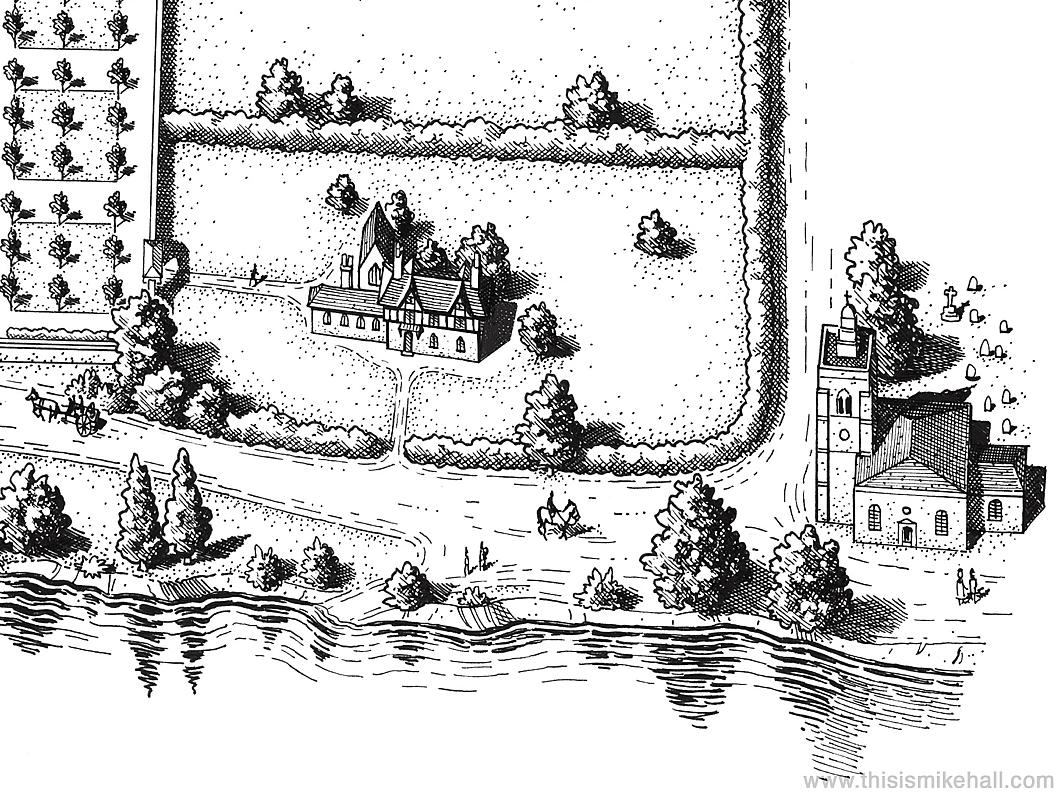

Thomas More’s London

There are almost as many Londons as there are Londoners. There’s Shakespeare’s London, Pepys’s London, Johnson’s London — even fictional characters like Sherlock Holmes have their own London.

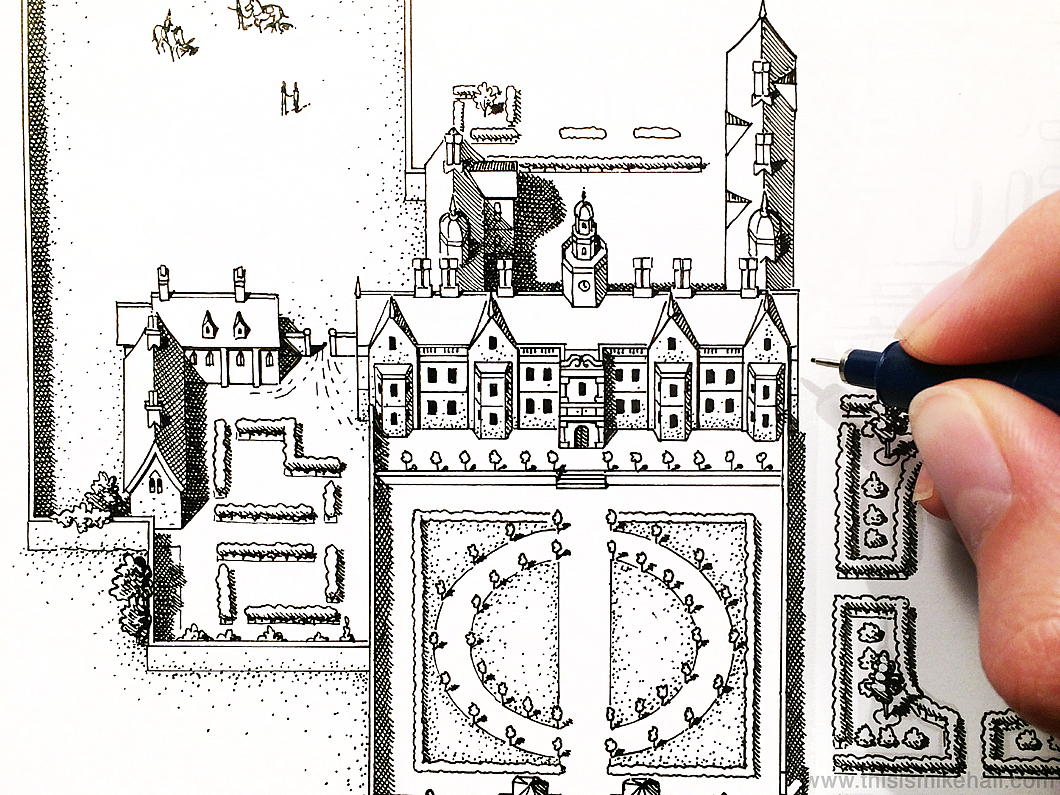

The city of Saint Thomas More takes form in a representation made by the excellent map designer Mike Hall, Harlow-born but now based in Valencia.

This map was commissioned from Hall by the Centre for Thomas More Studies in Texas and the designer based the view and the colour scheme on Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg’s map of London from their 1617 Civitates Orbis Terrarum

From his birthplace in Milk Street to the site of his execution, all the sites from the great points of More’s life are here in this map.

The future Lord Chancellor was educated at the school founded by the Hospital Brothers of Saint Anthony, one of the best in the City of London, and when he finished at Oxford returned to London to study law at New Hall and Lincoln’s Inn.

Crosby Place, the house that he bought in 1523 is not far from St Anthony’s School though its surviving remnant was moved brick by brick to Cheyne Walk in 1910 — a site close to More’s Chelsea residence of Beaufort House.

The chapel of Ely Place — town palace of the Bishop of Ely — still survives as St Etheldreda’s, the only mediæval church in London now in use as a Catholic parish.

God’s own Borough of Southwark gets a look in as well, with the Augustinian priory of St Mary Overs (now the Protestant cathedral of Southwark) and the town palace of the bishops of Winchester. Remnants of the great hall of Winchester Palace remains standing to this day.

As is the mapmaker’s privilege, Mr Hall has taken some liberties: in order to fit Lambeth Palace — the residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury (and Primate of All England) he’s shifted it a bit north of its actual spot.

I wish he’d kept the Rose and Globe theatres which he included in his initial sketch for the map — Southwark was the theatre district of its day.

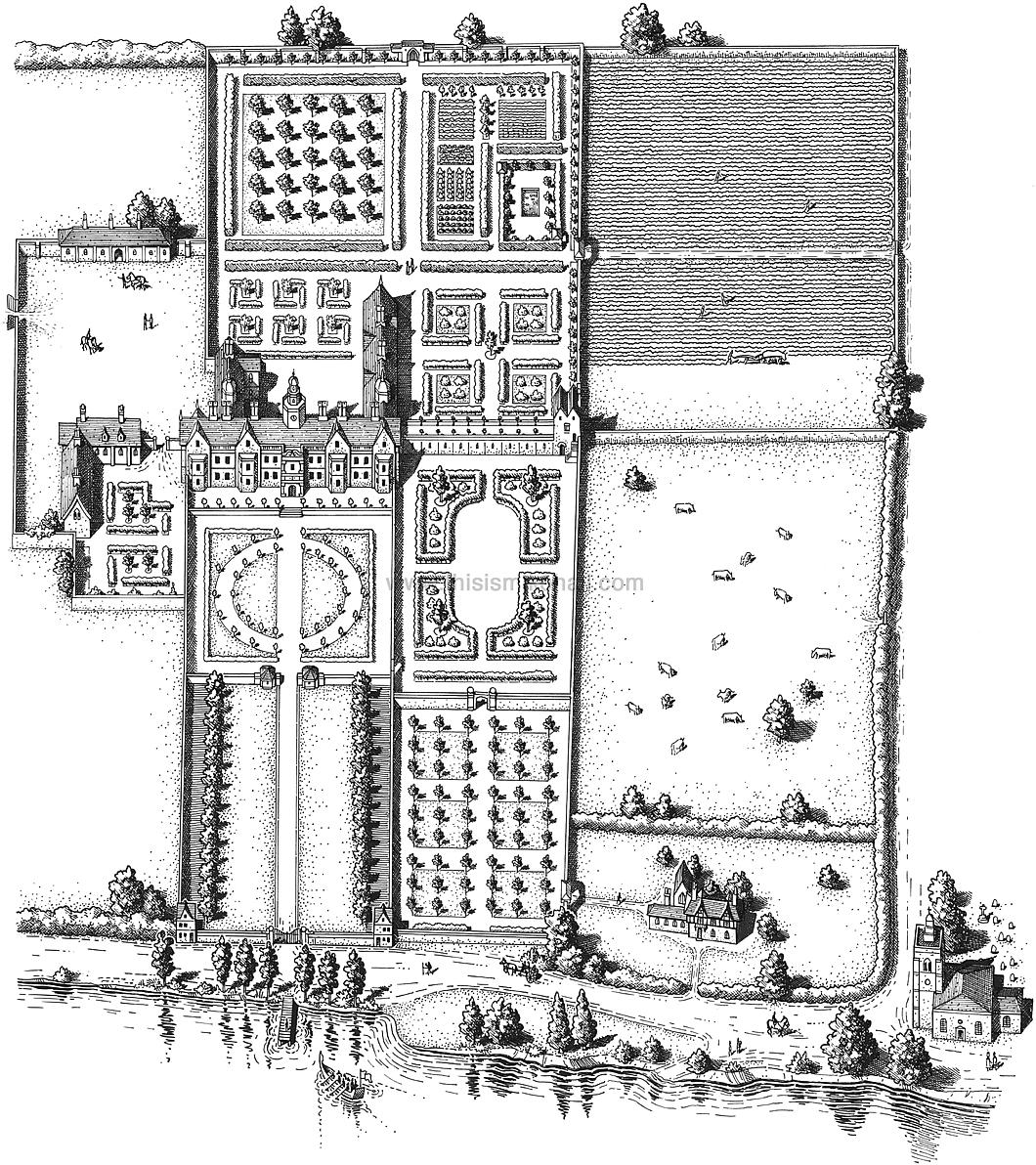

Hall also completed a sketch of Beaufort House as it would have appeared during St Thomas More’s lifetime. The house was demolished in 1740, and today’s Beaufort Street runs the line of the main drive leading up to it.

The Church of All Saints at Chelsea (now known as Chelsea Old Church) is at the bottom of the sketch and is where the More family burial vault is. His severed head is believed to be entombed there to this day.

Anglo-Gaullist Reading Update

The latest round of news or commentary of Gaullist content or interest:

Mercator: Charles de Gaulle: a wise ruler of France

Financial Times: France invokes the golden age of de Gaulle

Politico: Why all French politicians are Gaullists

Variety: Cliché-Ridden ‘De Gaulle’ is Unworthy of Its Iconic Subject

Scoring the Hales

One of the great Northumbrian traditions is the yearly Scoring the Hales, a mediaeval football match between the parishes of St Michael and St Paul in Alnwick. The first records of this match are from 1762 but it almost certainly began many, many generations earlier. This year’s match marked a return after a two-year absence thanks to the virus.

The match takes place every Shrove Tuesday but this is football as seen long before the modern rules of the sport were codified into ‘soccer’ (association football) and ‘rugger’ (rugby football).

The day begins with the Duke of Northumberland dropping the ball from the barbican of his seat, Alnwick Castle. Led by the Duke’s piper, the two teams are led down the Peth to the furlong-deep pitch beside the River Aln called the Pastures.

Rules are very few but the match consists of two teams of usually about 150 players from their respective parishes, battling it out over two halves of half-an-hour each. The goal posts are covered with greenery and stand 400 yards apart. Whoever scores two ‘hales’ first is deemed the winner. If the score is even after two periods, a further 45-minute period decides the match.

Once the match is over, the football is then thrown in the River Aln and all the players scramble to capture it and whoever gets it through the river to the other bank is allowed to keep it.

Like golf, Scoring the Hales used to be played in the streets but its destructive potential has seen it moved to an open space — here in Alnwick’s case since the 1820s.

The Newcastle Chronicle (founded 1764) sent a photographer along to this year’s match, duly won by the denizens of St Paul’s parish. (more…)

The Nicolaasjaar

Catholic Amsterdam Proclaims a Year of Saint Nicholas

A TINY RELIC of Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker has provided an excuse for Amsterdam Catholics to organise a whole year of festivities dedicated to the holy man and his legacy. The Basilica of St Nicholas stands just across from Centraal Station, gateway to the Dutch capital for so many visitors, and the parish has received as a gift the relic from the Benedictine abbey of St Adalbert’s in Egmond.

The tiny sliver of St Nicholas’s rib was enshrined in the Basilica at a special Mass opening the Nicolaasjaar on the eve of the saint’s feast in December. Bishop Jan van Burgsteden presided and prayers were also offered for HKH Princess Catharina-Amalia whose eighteenth birthday fell days later on 7 December.

The opening of the year met with wide coverage in the media, with even the website of the city proclaiming “There will always be a bit of Sinterklaas in Amsterdam from now on”.

“Saint Nicholas is really coming to Amsterdam now,” deacon Rob Polet told the evening news on Dutch television, “and here he will stay”.

“From the Friesch Dagblad to the Nederlands Dagblad, from Trouw to De Telegraaf: hardly any newspaper wanted to miss it,” the parish reports. “De Stentor, the Eindhovens Dagblad, the Zeeuwse PZC, and many other titles spread the news of St Nicholas. NRC Handelsblad and Het Parool even used it twice.”

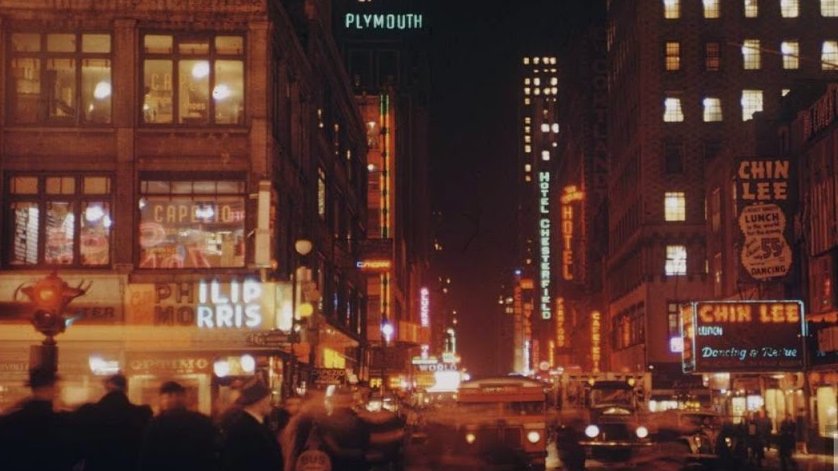

Three Bedrooms in Manhattan

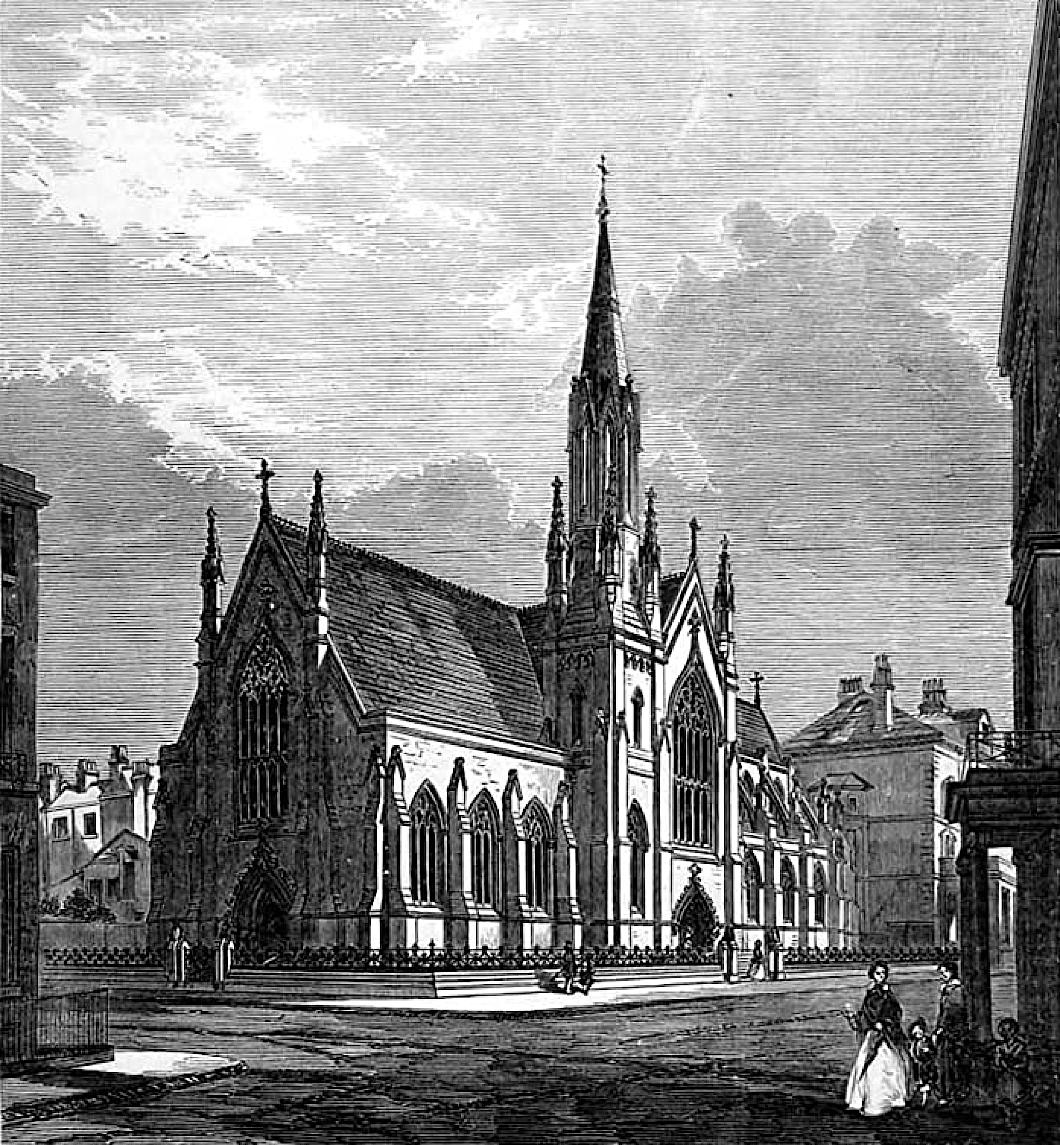

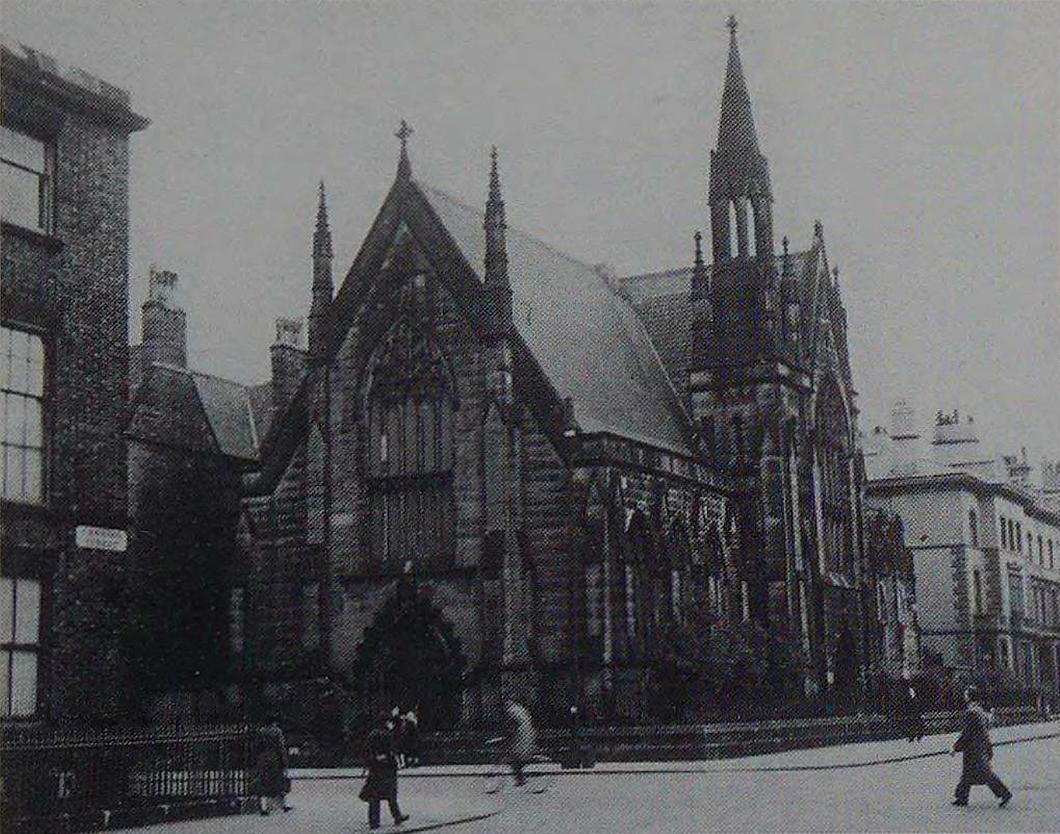

Liverpool’s Irvingite Church

The soi-disant “Catholic Apostolic Church” was one of the strangest but most fascinating Protestant sects the Victorian world brought forth. It was entirely novel — perhaps outright bizarre is a better description — in its combination of millenarian theology, evangelical preaching, and inventive ceremonialism. They were often referred to as Irvingites as a shorthand, owing to their origins amongst the followers of the Rev. Edward Irving, a Church of Scotland minister who led a congregation in Regent Square, London.

The Irvingites — after the death of Irving, it must be said — invented an elaborate hierarchy of twelve “apostles”, under whom served “angels”, “priests”, “elders”, “prophets”, “evangelists”, “pastors”, “deacons”, “sub-deacons”, “acolytes”, “singers”, and “door-keepers”. Coming from a very Protestant, low-church background, they curiously concocted elaborate liturgies influenced by Catholic, Greek, and Anglican forms of worship.

Another unique aspect of this group was its lack of denominational thinking: the Catholic Apostolic Church did not demand any strict or exclusive communion but was happy for its members and supporters to continue to be members of other churches or denominations.

One of the founding “apostles” of the Irvingite Church, Henry Drummond, married his daughter off to Algernon Percy, later the 6th Duke of Northumberland. That duke and his two immediate successors were known to be supporters of the Catholic Apostolic Church without disowning their established Anglican affiliation.

Despite this aristocratic land-owning connection, socially the Irvingite church spread most rapidly amongst the well-to-do mercantile classes, which meant they had congregations in places like Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool, Edinburgh, and even Hamburg. They were also very strict about tithing, which — combined with their mercantile status — meant they had a fair amount of money to spend on church building.

In Liverpool their church was built on the corner of Canning Street and Catherine Street in 1855-56. The design by architect Enoch Trevor Owen was influenced by Cologne Cathedral, with a nave more than 70 feet high.

Owen later moved to Dublin where he was employed as architect to the Board of Works, though he also designed the Catholic Apostolic Church in that city as well. (Today that building serves as Dublin’s Lutheran Church.) There’s some indication he designed the Catholic Apostolic Church in Manchester, so he might very well have been a member of the sect himself.

Another centrally important fact about the Irvingites: they didn’t believe that their original “apostles” could appoint further apostles. So when the last living “apostle” ordained his last “angel”, no further angels and so forth could be created. It endowed the clergy of this unique branch of Protestantism with an effective end date, but you have to give them credit for sticking with it. The last “apostle” died in 1901, the last “angel” in 1960, and their last “priest” in 1971.

Gone are all their elaborate inventive liturgies, and unsurprisingly the congregations have tended to fade away as well. The last clergy often recommended the lay people in their charge attend Church of England services when their own services stopped. The body continues to exist, and beside paying for the maintenance of its properties also makes annual grants to mostly Anglican but also Catholic and Eastern Orthodox bodies. In some very rare places, like Little Venice, prayer services are still held.

Indeed they still own their great central church in Gordon Square in Bloomsbury, though its chief use in the past decades has been being rented out first to an Anglican university chaplaincy, and now to the use of High-Church Anglicans as well as an Anglican evangelical mission.

In Liverpool their church was given Grade II listing protection in 1978, possibly when prayers services were still being held. By 1982 the church was up for sale, but without a buyer it succumbed to a fire in 1986.

The church lingered in ruins until the late 1990s when it was demolished and a nondescript block of flats erected on the site.

Elsewhere: Liverpool: Then and Now | Velvet Hummingbee

Merton

The ‘House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford’ — more commonly called Merton College — is one of the smaller colleges in Oxford, located right next door to lovely little Corpus.

Aside from rendering the architecture well, townscapes from the eighteenth century often give delightful little hints of city life. Michael Rooker (1746–1801) painted this scene of Merton College from its eponymous street in 1771, and the view today is hardly changed at all.

One of my favourite cityscapes is Canaletto’s view of the back end of Downing Street looking towards the old Horse Guards which you can pop into the Tate and see thanks to the generosity of Lord Lloyd-Webber. Incidentally, both scenes depict carpets being hung out for beating.

If you love the capital of the Netherlandosphere I recommended adding to your library Kijk Amsterdam 1700-1800: De mooiste stadsgezichten (‘See Amsterdam 1700-1800: The Most Beautiful Cityscapes’), the well-produced catalogue of the 2017 exhibition of the same name at the Amsterdam City Archives which includes 300 illustrations in full colour.

It’s high time the Museum of Oxford or the Ashmolean — or anyone really — put together a similar exhibition of Oxford cityscapes from the same century.

Incidentally, it was in Merton Field as a teenager that I played my first game of cricket. Who would have guessed then that eighteen years later your humble and obedient scribe would be facing the Vatican on the field of battle in the same sport? (We lost.)

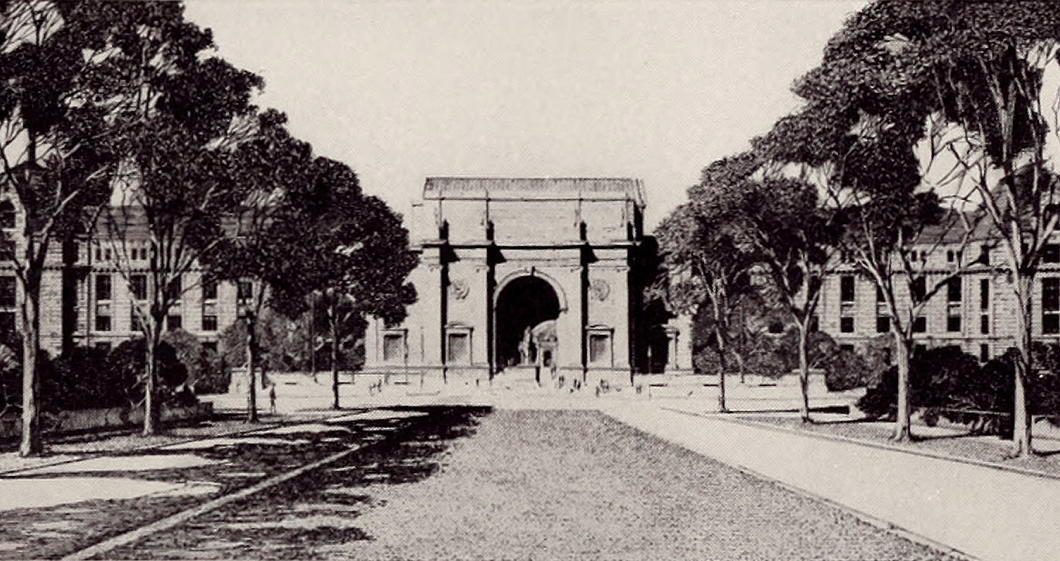

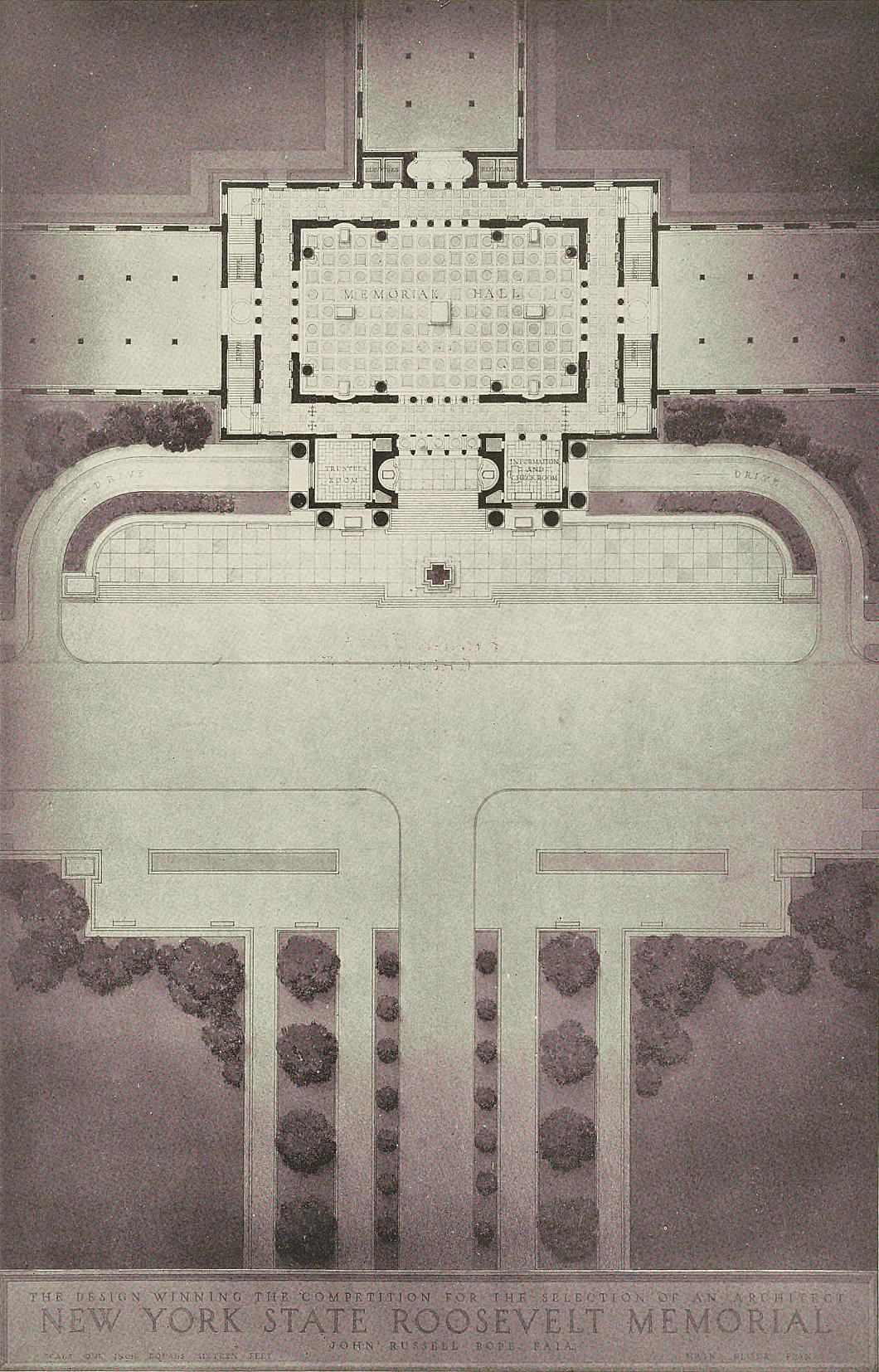

An Approach Not Taken

John Russell Pope’s Unexecuted ‘Museum Walk’

While John Russell Pope won the competition to design the New York State Theodore Roosevelt Memorial currently under attack, not every aspect of his design was executed.

The architect planned for an avenue to be built in Central Park to provide a suitable approach to the American Museum of Natural History and his memorial to the twenty-sixth president.

160 feet wide and 500 feet long, it would feature a broad central lawn flanked by drives and forming an allée of trees. Other versions of the plan have a roadway heading down the middle of the approach.

The idea of this ‘museum walk’ was originally that of Henry Fairfield Osborn, for a quarter-century president of the American Museum of Natural History.

Osborn was also president of the New York Zoological Society — they who run the Bronx Zoo — while his brother was president of the Metropolitan Museum across Central Park.

His son Fairfield also led the NYZS (renamed the Wildlife Conservation Society in 1993) and both père et fils held dodgy pseudoscientific Malthusian views about race and eugenics.

Their family house, Castle Rock, has one of the finest views of West Point across the Hudson and is still in private hands.

For whatever reason — possibly not wanting to redirect the 79th Street Transverse Road through the park that was in the way — Obsborn/Pope’s approach was never built.

It’s a shame as, aside from augmenting the impact of Theodore Roosevelt Memorial, it also would have provided a better vista from the steps of Museum itself.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories