World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

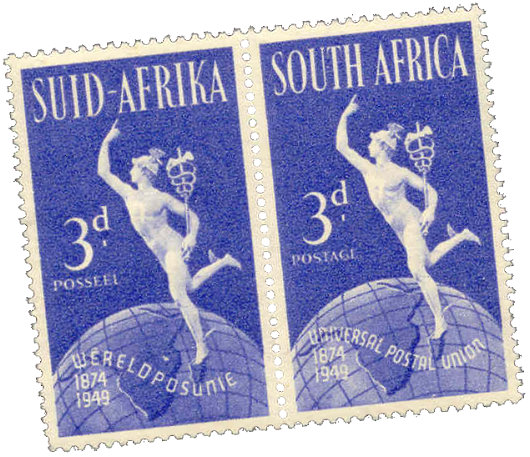

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Cropsey in the City

Jasper Francis Cropsey, A View in Central Park — The Spire of Dr. Hall’s Church in the Distance

Oil on canvas, 17⅛ in. x 12⅛ in.

1880, Private collection

THE HUDSON RIVER SCHOOL artist Jasper Francis Cropsey has obtained of late an almost cult-like following, the kool-aid being distributed from the well-oiled machinery of the Newington-Cropsey Foundation in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. Whether the object of worship is worthy of the faithful’s adulation is a matter of some speculation, but it’s admittedly refreshing to see a fan base surrounding a painter of the old school rather than one of the numerous gimmicky hacks floating around the New York art scene these days. Cropsey (like most Hudson River painters) is known for his luscious landscapes, so I thought it markedly unusual when I stumbled upon this painting, a cityscape. The artist’s vantage point is from The Pond in Central Park, looking over Fifty-ninth Street (Central Park South) towards where the old Plaza Hotel now stands. (more…)

S.R.E. & S.R.I.

Left, a prince of the Holy Roman Church and right, a prince of the Holy Roman Empire.

Credit: I think this is one of Zygmunt’s photos.

A Classical Summer in New York

ICA&CA 2009 Fellows’ Summer Lecture Series

One of our greatest institutions here in New York is the Institute of Classical Architecture & Classical America which does such splendid work in propagating knowledge about and training in classical architecture and its allied arts. Every summer the ICA&CA presents a series of summer lectures, the first of which takes place next Wednesday. This year the series will be held in the library of the General Society (f. 1785), New York’s last remaining guild, whose 44th Street headquarters house the Institute’s offices.

One of our greatest institutions here in New York is the Institute of Classical Architecture & Classical America which does such splendid work in propagating knowledge about and training in classical architecture and its allied arts. Every summer the ICA&CA presents a series of summer lectures, the first of which takes place next Wednesday. This year the series will be held in the library of the General Society (f. 1785), New York’s last remaining guild, whose 44th Street headquarters house the Institute’s offices.

In celebration of the quadricentennial of Captain Henry Hudson’s

sailing expedition on the river that now bears his name.

The Sanctified Landscape: Memory, Place, and the Mid-Hudson Valley in the Nineteenth Century

by Dr. David Schuyler, Professor of American Studies, Franklin & Marshall College. Sponsored by Hammersmith Studios.

17 June 2009

A Geography of the Ideal: The Hudson River and the Hudson River School

by Linda Ferber PhD, Executive Vice President & Museum Director of the New-York Historical Society. Sponsored by P.E. Guerin, Inc.

24 June 2009

Historic Hudson River Houses 1663-1915

by Gregory Long, President and CEO of The New York Botanical Garden. Sponsored by Peter Cosola, Inc.

8 July 2009

Edgewater: Building Classical Architecture along the Hudson River

by Michael Middleton Dwyer, architect and editor (Great Houses of the Hudson River, Bullfinch Press, 2001). Sponsored by Andrew V. Giambertone and Associates, Architects, PC.

General Society Library

No. 20, West 44th Street

Receptions at 6:30 pm

Lectures to follow at 7:00 pm

The ICA&CA Summer Lecture Series is free to ICA&CA Members and employees of Professional Member Firms, as well as all students with current identification. General Admission is $20 per lecture; $65 for the full series. Click here to become a member.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York Council for the Humanities and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs. Special thanks to Balmer Architectural Mouldings.

Enda & Declan

“Now you wouldn’t go scuppering this Lisbon deal we’ve got now wouldja, Mr. Ganley?” Mr. Enda Kenny of Fine Gael (left) meets Mr. Declan Ganley of Libertas (right).

While I am accused of being Fine Gael by tribe & temperament, there’s no doubting that party’s been heading in the wrong direction for several decades now. Once moderate in the face of supposed republican extremism, it is now a banal shell of its former self. (Who would Gen. Mulcahy vote for today, one wonders). Those who have the opportunity of voting in the current European elections will doubtless consider voting for Mr. Ganley’s Libertas party, which is running candidates in quite a number of EU member states, including the United Kingdom.

St. Stephen and the Virgin & Child

The Hungarian Bishops’ Conference has a surprisingly handsome logo (above) depicting their patronal saint, King Stephen I, bestowing his crown to the Blessed Virgin and Our Saviour. Some might think the depiction of the Madonna & Child a touch too cartoonish, but I enjoy it.

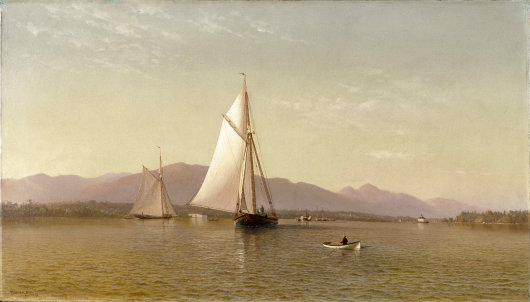

The Tappan Zee in the Age of Rig & Sail

Julian Oliver Davidson, The Hudson River from the Tappan Zee

Oil on canvas, (size not on record)

1871, Private collection

Francis Augustus Silva, On the Hudson near Tappan Zee

Oil on canvas, 20 in. x 36 in.

1880, Private collection

Francis Augustus Silva, The Hudson at the Tappan Zee

Oil on canvas, 24 in. x 42 3/16 in.

1876, Brooklyn Museum

A Dutch Organ in a Chelsea Church

THE ORGAN AT the Church of the Holy Apostles on Ninth Avenue in Chelsea has a brief history that spans three lands: the Netherlands, Texas, and New York. Mr. Joseph Mooibroek of Fairview, Texas was born in the Netherlands but emigrated to the United States in his youth and found his fortune there. Mr. Mooibroek (whose surname is Dutch for “beautiful trousers”) and his wife wanted an organ for the great hall of the castle they built in Texas, and appropriately he chose the Dutch firm of Van den Heuvel to construct the organ in 1994. Among Van den Heuvel’s other works are the organ at Saint-Eustache in Paris (1989, the largest organ in France), and that in the Duke’s Hall of the Royal Academy of Music in London (1993).

The Tele-tab

The Daily Telegraph prides itself on being Britain’s top-selling quality daily newspaper, but the dear old Telly has being playing tabloid of late. Compare this 2004 front page (left) to one of just a few days ago (right).

The point of a headline in a quality newspaper should be to inform the reader of what the article is about, as well as to impart information quickly to those who are scanning the page. “Payback time” the Telegraph boldy asserts, but what on earth does that tell us? Nothing; we have to go to the subheadline to find out “Cameron orders Tories to refund excessive expenses; Hazel Blears to meet £13,332 tax bill on second home”.

There is an art in creating a headline that is both punchy and informative without being vulgar, but the Telegraph seems to have abandoned this art — for now, at least.

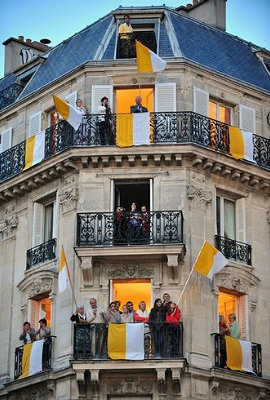

Le Pape à Paris

While Benedict XVI is currently in the headlines for his visit to the Holy Land, here is a translation into French by Béatrice Bohly of my piece on Benedict’s visit to Paris last year.

La devise de la ville de Paris, Fluctuat nec mergitur est parfaitement appropriée: « Battue par les flots, elle ne sombre pas ». Difficile de trouver des mots plus aptes à décrire la barque de Pierre, dont le Saint-Père, le pape, a passé ces deux jours dans la capitale française. Depuis des temps immémoriaux, la France a été considérée comme « la fille aînée de l’Eglise », son siège de primauté de Lyon ayant été établi au cours du deuxième siècle et Clovis, son premier roi chrétien, ayant reçu le baptême en 498. Mais à côté de 1.500 ans de christianisme, au cours des deux derniers siècles, la France, a également servi de fonds baptismaux à la révolution et à la rupture – dans l’esprit-même de ce premier “non serviam” (phrase attribuée à Lucifer, refusant de servir Dieu, ndt) .

La devise de la ville de Paris, Fluctuat nec mergitur est parfaitement appropriée: « Battue par les flots, elle ne sombre pas ». Difficile de trouver des mots plus aptes à décrire la barque de Pierre, dont le Saint-Père, le pape, a passé ces deux jours dans la capitale française. Depuis des temps immémoriaux, la France a été considérée comme « la fille aînée de l’Eglise », son siège de primauté de Lyon ayant été établi au cours du deuxième siècle et Clovis, son premier roi chrétien, ayant reçu le baptême en 498. Mais à côté de 1.500 ans de christianisme, au cours des deux derniers siècles, la France, a également servi de fonds baptismaux à la révolution et à la rupture – dans l’esprit-même de ce premier “non serviam” (phrase attribuée à Lucifer, refusant de servir Dieu, ndt) .

Ce fut le penseur français Charles Maurras – lui-même non-catholique jusqu’à la fin de sa vie – qui a conçu de la notion que (depuis la révolution) il n’y avait pas une France mais deux : le pays réel et le le pays légal. La vraie France, catholique et droite, contre la France officielle, irreligieuse et artificielle. Tout comme Maurras différenciait les deux visions de la France, nous, dans le monde d’expression anglaise, savons que l’Angleterre est vraiment un pays catholique qui souffre d’un interregnum de quatre-siècle (de même que l’Ecosse, et l’Irlande, et l’Amérique, et le Canada, et l’Australie…). Nous aimons nos patries mais nous savons qu’elles ne sont pas vraiment elles-mêmes – elles ne reflètent pas vraiment cette idée de leur essence – jusqu’à ce qu’elles jouissent de la plénitude de la communion chrétienne.

A new look for The Walrus

The Walrus is Canada’s general-interest magazine, a sort of New Yorker for the Great White North. Founded just a few years back in 2003, it has taken many of its visual cues from The New Yorker and the result has been a very handsome monthly and a surprisingly interesting one. That’s not to say that it’s a very interesting magazine (like The Spectator), but one which surprises with the occasional article of note. Canada’s intelligentsia is notoriously boring and liberal; they tend to sneer at the neighbouring United States while simultaneously attacking long-held Canadian traditions. For some reason, Canadian intellectuals have yet to comprehend that making Canada less British doesn’t make it more Canadian but instead more American because it is precisely Canada’s Britishness that distinguishes the Great Dominion from the republic to the south.

Allies Day, May 1917

Childe Hassam, Allies Day, May 1917

Oil on canvas, 36½ in. x 30¼ in.

1917, National Gallery of Art (U.S.)

This has long been one of my favourite paintings, ever since I first saw it one day when I was very young while it was on loan to the Metropolitan. On a May day in 1917, Fifth Avenue was temporarily proclaimed “the Avenue of the Allies” and the British and French commissioners paraded down the boulevard with great ceremony. Childe Hassam set his easel on a balcony on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street and took in the splendid scene towards the Church of St. Thomas and the University Club. Patriotic displays were much more lively then, involving bursts of flags and banners, than the rather dull and monotonous display of the single Stars-and-Stripes that became widespread after the World Trade Center attacks.

Interestingly, “Avenue of the Allies” aside, the United States was not actually allied to France and Great Britain during the First World War. President Wilson thought the United States was not so lowly as to merely intervene in a biased manner on the side of those it had lent money, but rather for the high-minded goal of establishing justice (or, as we might honestly call it, the destruction of Catholic Europe). The U.S., then, was merely a “co-belligerent” rather than an “ally”, though obviously this high-minded euphemism was lost on most people. During the Second World War, Finland found itself invaded by the Soviet Union and abandoned by the West, so — having no taste for Hitler and his Nazi charades — they became “co-belligerents” with Germany, rather than concluding a more distasteful alliance.

Hassam, who died in 1935, had little time for the avant-garde schools of art that came after the Impressionism he practised, and described modernist painters, critics, and art dealers as a cabal of “art boobys”. He was almost forgotten in the decades after his death, but the rising tide of interest in Impressionism from the 1970s onwards lifted even the boats of American Impressionists, and his Flags series of paintings are widely-known and much-loved today.

Zuma’s Day

“PRAETORIA PHILADELPHIA” — Pretoria of Brotherly Love — was the formal name for the paramount of South Africa’s three capital cities. Pretoria, the jacarandastad, is home to the Executive; Cape Town, die moederstad, is home to the Parliament, and Bloemfontein, the “City of Roses”, is home to the High Court of Appeal. While the politics of government take place in Cape Town, its actual administration takes place in Pretoria, and all that flows forth from the stately Union Buildings that preside over the city from atop Meintjieskop. The Uniegebou is composed of two wings that come together in a semicircular amphiteatre, symbolizing the coming-together of Briton & Boer in the Union of South Africa. Designed by Sir Herbert Baker, Lutyens’ lieutenant in the building of New Delhi, some believe it to be his finest work.

Victory Day in Moscow

I recently discovered that we receive the television channel Russia Today in our humble little flat here in Stellenbosch, and have spent the past few days enjoying it. They are shockingly truthful (almost nasty) in their reporting of international relations, in so far as the truth — for the moment — tends to favour the Russian case in world affairs, and make NATO look like a bunch of ninnies. Saturday — May 9 — was Victory Day in Russia, in which the defeat of Nazi Germany in the Second World War is commemorated and celebrated. RT showed many minutes of splendid highlights from the great parade in Red Square, and I just sat and enjoyed it.

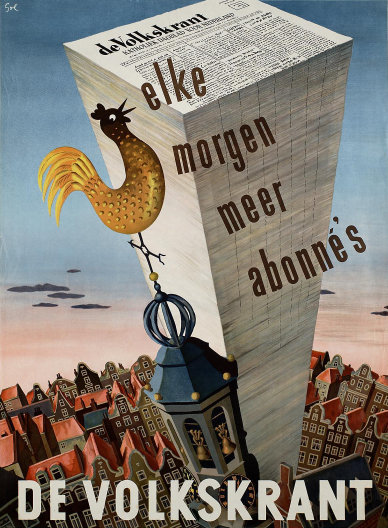

De Volkskrant

A FAVOURITE POSTER of mine combines a number of the things I love: newspapers, architecture, and the Netherlands. Arthur Goldsteen designed this handsome poster to advertise the daily newspaper De Volkskrant in 1950.

Boers, Peter Simple, and Pith Helmets

Sometimes something rather interesting is right under your nose and you never even notice it. I read the Catholic Herald — the premier Catholic newspaper in the English-speaking world — every week and have been reading it since university days, but I have rarely read Stuart Reid’s “Charterhouse” column on the back page. A few recent perusals have exposed my foolishness for neglecting it. They are presented for your reading here.

(Of course, there has never been a columnist as brilliant as Peter Simple, whose works we have shown you in a series of installments.)

Charterhouse

by STUART REID

Everyone needs a secular hero or two, and one of mine is Rian Malan. In the Sunday Times at the weekend he had a very nice diary, in which he said that he liked Jacob Zuma, because the president-elect of South Africa had “old-fashioned views on stuff like law and order”.

Malan also said that it was a good time to be a Boer: “…as South Africa staggers towards its destiny, it’s white Left-liberals who are wailing about our government’s shortcomings. The Boers never expected any better, so we are generally immune to the gloom.”

The diary made my heart go out, once again, to the Boers. They are brave, honest, hard-working, courteous, old-fashioned and often God-fearing, with a weakness for the bottle. Plus they were on the right side in the Boer War and their women – sometimes their men too – are beautiful.

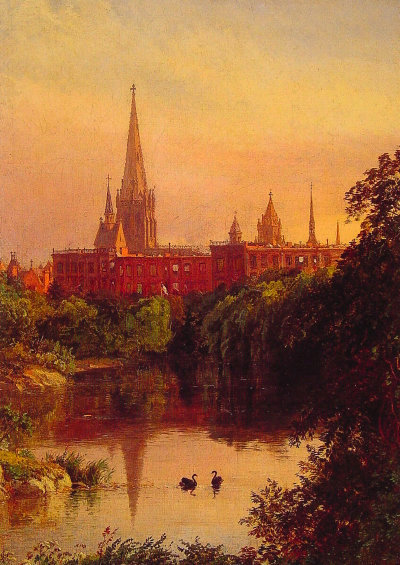

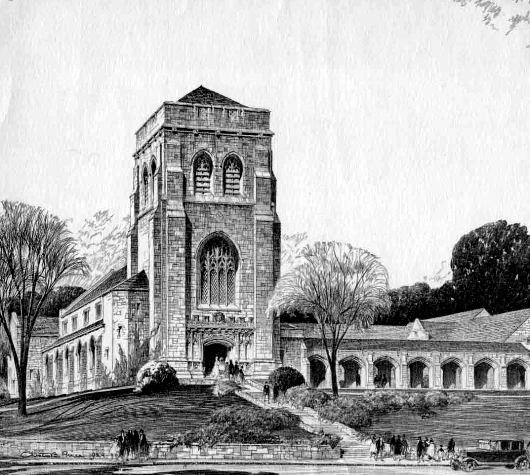

High Church Dutch Reformed

Not even the peaceful hills and dales of the Hudson Valley were left untouched by the liturgicalism of the Oxford Movement

SUCH WAS THE influence of the nineteenth-century “Oxford Movement” in the Church of England that it engulfed the great preponderance of the Anglican Communion. It is surprising when you consider that Anglican priests and even a bishop were jailed in England for such scandalous acts as calling the Communion service “the Mass”, wearing vestments, and putting candles on the altar; these are now so widespread in the Church of England to be commonplace. But the Oxford movement also spilled out into other Protestant groups as well. The liturgical movement changed the Church of Scotland in the 1900s, and many of the Kirk’s medieval church buildings that had been converted into pulpit-centered preaching halls were reordered in a way emphasizing the “Communion table” that was an altar in all but name. (Those who can find before & after shots of the ‘Toon Kirk’ of Holy Trinity in St Andrews, Fife will notice this marked contrast).

Peter Hitchens on America

On returning from America

I have spent the past two weeks in the United States, not working but travelling on my own account, revisiting some favourite places and coming up for air. It remains an exhilarating and beautiful place, wrongly sneered at by too many British people who simply haven’t experienced enough of it to know how good it can be, and how much worse off we would be if it weren’t there. But it is also a foreign country, not some kind of special friend – but a foreign country to which we have unique access because we speak a similar language. Only fluent French or German speakers could ever know as much about those countries as any British visitor can swiftly learn about the USA – if he wants to.

Rather than re-immerse myself in the small-scale squalor of British politics, which seems even less appealing or interesting than it was when I set out, I thought I would muse a little on what an English person experiences in the great republic, and what it means (or might mean) for us.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories