World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

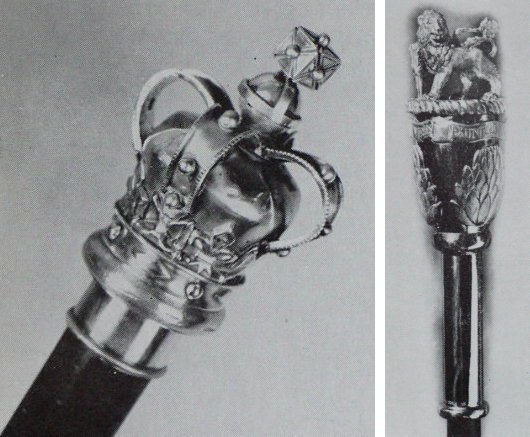

Black Rod — Swart Roede

In my post on the 1947 Royal Visit to Cape Town, I mentioned just in passing the title of the Draer van Swart Roede — or the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, as he is known in English. Well, here is the Black Rod itself. The original South African Black Rod (left) dates from the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope and was adopted as the Black Rod of the Union Parliament when South Africa was unified in 1910. After the abolition of the monarchy in 1961, a new Black Rod (right) was commissioned which featured protea flowers topped with the Lion crest from the South African coat of arms.

Black Rod (the person, not the staff) was the Senate’s equivalent of the House of Assembly’s sergeant-at-arms (ampswag). The first Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod in history was appointed in 1350 and the position still exists today in the British Parliament of today. Black Rod is sergeant-of-arms of the House of Lords, as well as Keeper of the Doors. The Usher’s best-known role is having the doors of the House of Commons ceremonially slammed in his face when he acts as the Crown’s messenger during each State Opening of Parliament, a ritual derived from the 1642 attempt of Charles I to arrest five members of parliament.

In South Africa, die Swart Roede traditionally wore wore a black two- or three-pointed cocked hat, a black cut-away tunic, knee breeches, silk stockings and silver-buckled shoes, but this costume of office has undergone a process of modernisation since the 1950s. After the vast expansion of the electorate in 1994 and introduction of an interim constitution, Black Rod’s title was officially shortened to “Usher of the Black Rod” to make it “gender-neutral”. (Regrettably, the Canadian Senate has also mimicked this innovation, though it is often unofficially ignored.) When a new, permanent constitution was enacted in 1997, the Senate was replaced by the National Council of Provinces as the upper house of parliament. A new Black Rod (the staff, not the person) was introduced in 2005, but is of such a garish design that it is best left uncommented upon.

The Band-leader & the Sergeant-Major

I came across these two characters in the Castle in Cape Town, the oldest building in South Africa and still home to the Cape Town Highlanders and Cape Garrison Artillery.

Heaven in Herefordshire

In the weekly South African edition of the Telegraph, I came across a brief note marking the death of England’s oldest publican, Flossie Lane of ancient Leintwardine in Herefordshire. From the internet, I find the full version of her obituary, which is reproduced below. The Sun Inn, with its “Aldermen of the Red-Brick Bar” sounds like a splendid haven.

Flossie Lane, who died on June 13 aged 94, was reputedly the oldest publican in Britain, and ran one of the last genuine country inns

For 74 years she had kept the tiny Sun Inn, the pub where she was born in the pre-Roman village of Leintwardine on the Shropshire-Herefordshire border.

As the area’s last remaining parlour pub, and one of only a handful left in Britain, the Sun is as resolutely old-fashioned and unreconstructed today as it was in the mid-1930s when she and her brother took it over.

According to beer connoisseurs, Flossie Lane’s parlour pub is one of the last five remaining “Classic Pubs” in England, listed by English Heritage for its historical interest, and the only one with five stars, awarded by the Classic Basic Unspoilt Pubs of Great Britain.

She held a licence to sell only beer – there was no hard liquor – and was only recently persuaded to serve wine as a gesture towards modern drinking habits.

With its wooden trestle tables, pictures of whiskery past locals on the walls, alcoves and a roaring open fire, the Sun is listed in the CAMRA Good Beer Guide as “a pub of outstanding national interest”. Although acclaimed as “a proper pub”, it is actually Flossie Lane’s 18th-century vernacular stone cottage, tucked away in a side road opposite the village fire station.

There is no conventional bar, and no counter. Customers sit on hard wooden benches in her unadorned quarry-tiled front room. Beer – formerly Ansell’s, latterly Hobson’s Best at £2 a pint – is served from barrels on Flossie Lane’s kitchen floor. (more…)

A humble house in Buenos Aires

Landowner Ignacio Pirovano rests in his family’s Buenos Aires townhouse, 1964.

Our Cardinal at the Oratory

His Eminence Keith Patrick O’Brien, Cardinal Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh, at the Brompton Oratory for the Feast of St. John the Baptist this year.

(From the NLM)

First Things, Three Songs

Through an interesting post by Joseph Bottum on the First Things blog, I discover that R. R. Reno posted all three of the songs I elaborated upon in my June 2007 post “We’ve Lost More Than We’ll Ever Know”, though (so far as I can tell) he arrived at the same three without stumbling across my entry on them. I always read First Things in New York (it’s one of my favourites, and simply a must-read), but it’s sadly not available in South Africa (bar actually scraping one’s pennies together for a subscription) so I’ll just have to wade through friends’ archives when I return to the Empire State. (Or does the Society Library have a subscription? And if not, why not?).

While it has a reputation among some Catholics as being a bit too liberal & democratist, I suspect the whiff of Americanism one finds in the pages of First Things is akin to the aroma of tobacco in an old bar: the smell lingers but that doesn’t mean anyone’s actually still smoking. Nonetheless, they often feature top-notch articles and writing that are of interest to Catholics & other traditionalists.

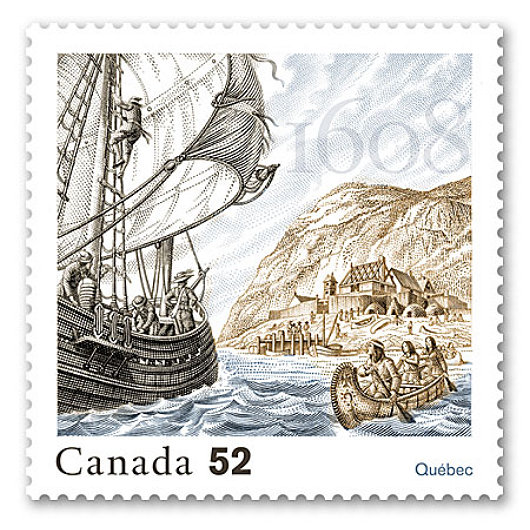

Quebec Stamp

This stamp was designed by Jorge Peral, the artistic director of the Canadian Bank Note Company, for Canada Post to commemorate the four-hundredth anniversary of the foundation of Quebec.

A Good Day in Cape Town

The South African Royal Family’s 1947 visit to “Die Moederstad”

SOUTH AFRICA IS a nation that took a long time birthing, from the first steps van Riebeeck took on the sands of Table Bay in 1652, through the tumult of the native wars, the tremendous conflict between Briton & Boer, and ultimately what was hoped would be the final reconciliation in Union of South Africa — 1910. In that year, young Prince Albert of York & of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was just fifteen years of age, and South Africa became a dominion just weeks after his father became King George V.

Albert was the second son of a second son, so at the time of his birth (and for most of his early life) it was never expected that he would one day be King of Great Britain, Emperor of India. It was his brother’s abdication that thrust poor Bertie, as he was always known to his loved ones, upon the throne imperial. It was a cold December day in 1936 that the heralds of the Court of St. James proclaimed him George VI.

By his nature, the King was a quiet and reserved man, partly because of the stammer that impeded his speech. George VI was happiest among his family, and they accompanied him in 1947 on a long voyage aboard HMS Vanguard, to his far-off kingdom on the other side of the world, where the two oceans meet. It was the first time a reigning monarch has set foot on South African soil, and Capetonians waited in earnest anticipation to see their sovereign. How appropriate that this happy city — moederstad, or “mother-city”, of all South Africa — would be the first to receive him. (more…)

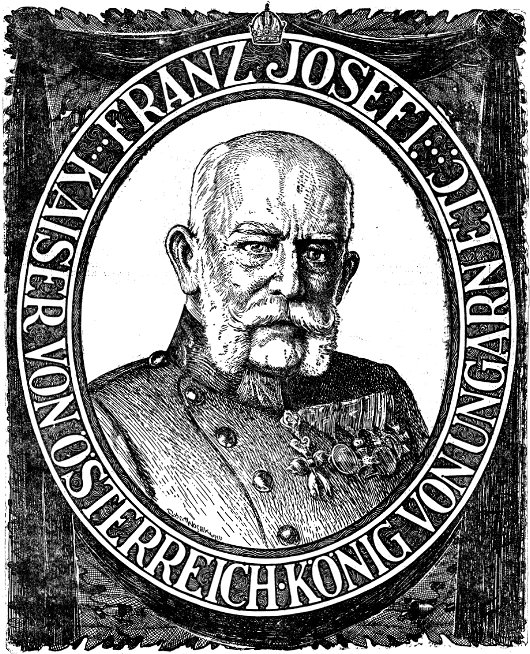

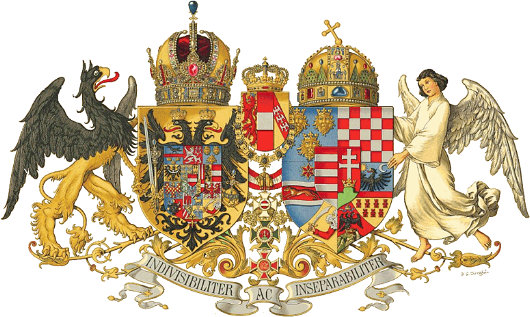

The Young Emperor

A reader notes in correspondence that Franz Joseph was not always old — though the popular conception certainly is of the Emperor in his later years. Here is the young Franz Joseph (or Ferenc József), just five years after he became Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, Bohemia, &c. The Emperor became so at such a young age because his father, Ferdinand I, abdicated after the revolts of 1848.

This portrait is by the Hungarian painter Miklós Barabás, who also completed portraits of the composer Franz Liszt, the novelist Baron József Eötvös de Vásárosnamény, William Tierney Clark, the Bristol engineer responsible for Budapest’s famous Chain Bridge, and many, many others.

The Goerke House, Lüderitz

THE FAMILIAR PHRASE has a person in difficult circumstances being “between a rock and a hard place”. The Namibian town of Lüderitz is stuck between the dry sands of the desert and salt water of the South Atlantic — this is the only country whose drinking water is 100% recycled. Life in this almost-pleasant German colonial outpost on the most inhospitable coast in the world has always been something of a difficulty, but the allure of diamonds has at least made it profitable. One such adventurer who came from afar and made his fortune in this outer limit of the Teutonic domains was one Hans Goerke. (more…)

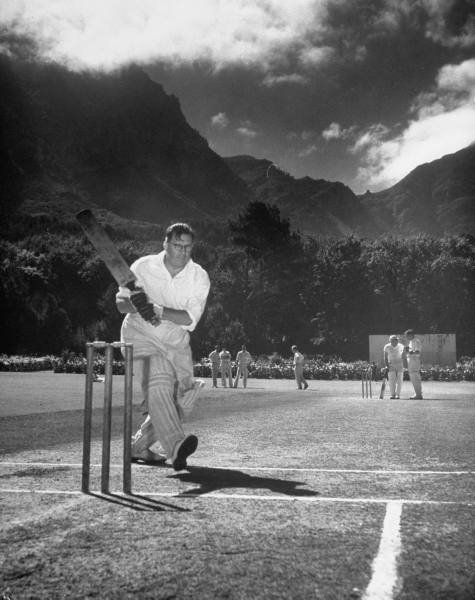

Minister van krieket

The Minister of the Interior, Mr. Theophilus Ebenhaezer Dönges, practises his swing while playing for the National Party cricket team.

The Huguenot Monument, Franschhoek

AMONG THE MANY peoples who, through the various vicissitudes of history, have found their home in South Africa are the Huguenots, or French Protestants. These people have always had a certain fascination for me, having being born so close to New Rochelle, the city in the New World founded by Huguenot refugees. The city’s public high school is a rather stately French neo-gothic chateau in the middle of Huguenot Park.

My own alma mater — a smaller private school in New Rochelle — counted Huguenot descendants among its first students and there was at least one remaining in my own school days. Street names such as Flandreau, Faneuil, and Coligni betray the French heritage of the city’s founders, and Trinity Church still has the old communion table brought over from La Rochelle. (more…)

The eternal specter of the National Party

Above: Irish journalist Fergal Keane interviews a poor black South African.

This recent general election in South Africa marked the first time since 1910 — the year the country was unified as an independent dominion — that voters weren’t given the option of voting for the Nationalists. The party was founded in time for the 1914 election, and first entered government in coalition with the Labour party in 1924, but their most famous victory was in the general election of 1948. It was then that they won an outright majority and introduced the ideology of apartheid. The famous Brazilian counter-revolutionary Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira was of the opinion that South Africa had been in the process of developing a genuinely feudal society until the introduction of apartheid put a full-stop to this evolution.

Evil and heretical though apartheid was, such are the wounded and fearful hearts of men that it won for the National Party each successive general election until the introduction of universal suffrage in 1994. Admittedly, a large proportion of the Nationalist vote was not necessarily a vote for apartheid but instead a vote against communism. Soviet-backed communist subversion escalated sharply throughout Africa in the 1950s, especially as Nelson Mandela launched his internal coup taking over the previously broad-based & non-violent African National Congress and transforming that body into an officially and openly Soviet-aligned group with a terrorist wing whose activities rightly landed him in jail.

With the end of apartheid, the Nationalists had to contend with a universal adult electorate of every South African over eighteen years of age. In 1989, the last election under apartheid, over 2,000,000 whites, 261,000 coloureds (mixed-race people), and 154,000 Indians took advantage of their right to vote. In 1994, meanwhile, over 19.5 million voted. Most interestingly, the votes of the (mostly Afrikaans-speaking) coloured population — whose right to vote was taken away by the Nationalists in the 1950s before being quasi-reintroduced in 1984 — turned around and voted for the National Party en masse, out of fear for the behemoth of the black-dominated ANC.

The party still came second in the 1994 election with 20% of the vote — a respectable result considering the massive media push supporting Mandela & the ANC. But the National Party refused to take advantage of their showing. Under their supremely naïve leader, F. W. de Klerk, instead of forming a noticeable opposition to the ANC behemoth and thus laying the foundations for a robust tradition of antagonistic government and opposition debating eachother, the Nationalists did the worse thing imagineable and actually joined the government (as did the leaders of the black-conservative Inkatha Freedom Party). Had the Nationalists & Inkatha joined forces then as a united multi-racial moderate conservative opposition to the ANC, South Africa’s democracy would be in a much healthier state than it is today. Instead, they chose the gravy train and the voters have punished them in every subsequent election.

For their sins of opportunism, the Nationalists were rightly abandoned by voters and eventually the party dissolved itself and more-or-lessed merged into the ANC they had spent decades proclaiming the dangers of. Marthinus van Schalkwyk, the last leader of the Nationalists, is today an ANC member and cabinet minister. (Here I must concede that he is actually quite a capable minister and was a very sound conservationist as Minister for the Environment; his current portfolio is Tourism).

So April 2009 was the first general election since the dissolution of the National Party. F. W. de Klerk cast his vote in front of the news cameras and refused to divulge which of the parties got his vote, except that it was for an opposition party. Nonetheless, there were a number of eccentric parties which positioned themselves as new-born versions of the Nationalists. One, founded by a known charlatan and fraudster, actually claimed the name “National Party” and was quite multi-racial in its composition with a broadly populist agenda. Another, the “National Alliance“, was a primarily coloured group based in the Northern Cape. Both, however, used variants of the sun logo employed by the old Nationalists. How did they do? Well, rather predictably, convincing voters to back a party whose two best-known polices are first, apartheid, and second, sucking up to the ANC, was not an easy task. Both parties of a neo-Nat persuasion failed miserably, and I think it’s safe to say we’ll hear little of them again.

Still, the National Party’s forty-six straight years in power obviously impacted the history of this country, and their legacy lurks like a specter in the back of the minds of many. Eccentrics who try to resurrect this dead corpse, however, will swiftly be relegated to the cabinet of curiosities.

A new look for Argentina’s Herald

The Buenos Aires Herald is one of those newspapers that, by the grace of God, simply must continue existing no matter what horrors befall the newspaper industry as a whole. Finding up-to-date information on Argentina, in English, can be exceptionally frustrating and I had the Sunday version of the paper sent to me in New York every week; perfect reading for the train ride into work. Martin Gambarotta’s “Politics & Labour” column has to be one of the most informative and well-written political columns in any English-speaking newspaper. I also enjoyed the paid announcements section, informing readers of golf tournaments in aid of the Hospital Británico, meetings of the British-Argentine Chamber of Commerce, and when the next convocation of the South America Piping Association would be held. That said, when the Herald started denominating their subscription fee in dollars instead of pesos, I had to call it quits — though very reluctantly.

All the time while perusing the newspaper, however, I kept thinking “This could be better…”. Readers know how design-obsessed I am, especially when it comes to newspapers, and the Buenos Aires Herald would be such a better newspaper if they just tweaked a few things: a more judicious font choice, standardized white-spaces between columns, a few meliorations here and there. But now they’ve gone and redesigned the thing — without seeking the input of this devoted fan! — and they’ve got it all wrong. (more…)

The Queen at the Armory

Queen Elizabeth II & the Duke of Edinburgh attend a ball in their honour at the Seventh Regiment Armory in New York; October, 1957.

Praying with the Kaisers

by JOHN ZMIRAK

INSIDECATHOLIC.COM

As I’m writing this column at the tail end of my first trip to Vienna, some of you who’ve read me before might expect a bittersweet love note to the Habsburgs — a tear-stained column that splutters about Blessed Karl and “good Kaiser Franz Josef,” calls this a “pilgrimage” like my 2008 trip to the Vatican, and celebrates the dynasty that for centuries, with almost perfect consistency, upheld the material interests and political teachings of the Church, until by 1914 it was the only important government in the world on which the embattled Pope Pius X could rely for solid support. Then I’d rant for a while about how the Empire was purposely targeted by the messianic maniac Woodrow Wilson, whose Social Gospel was the prototype for the poison that drips today from the White House onto the dome of Notre Dame.

And you would be right. That’s exactly what I plan to say — so dyed-in-the-wool Americanists who regard the whole of the Catholic political past as a dark prelude to the blazing sun that was John Courtenay Murray (or John F. Kennedy) might as well close their eyes for the next 1,500 words — as they have to the past 1,500 years.

But as I bang that kettle drum again, I want to set two scenes, one from a fine and underrated movie, the other from my visit. The powerful historical drama “Sunshine” (1999) stars Ralph Fiennes as three successive members of a prosperous Jewish family in Habsburg Budapest. The film was so ambitious as to try portraying the broad sweep of historical change — and, as a result, it was not especially popular. What historical dramas we moderns tend to like are confined to the tale of a single hero, and how he wreaks vengeance on the villains with English accents who outraged the woman he loved. “Sunshine”, on the other hand, tells the vivid story of the degeneration of European civilization in the course of a mere 40 years. The Sonnenschein family are the witnesses, and the victims, as the creaky multinational monarchy ruled by the tolerant, devoutly Catholic Habsburgs gives way through reckless war to a series of political fanaticisms — all of them driven by some version of Collectivism, which the great Austrian Catholic political philosopher Erik von Kuenhelt-Leddihn calls “the ideology of the Herd.”

From a dynasty that claimed its legitimacy as the representative of divine authority at the apex of a great, interconnected pyramid of Being in which the lowliest Croatian fisherman (like my grandpa) had liberties guaranteed by the same Christian God who legitimated the Kaiser’s throne, Central Europe fell prey to one strain after another of groupthink under arms: From the Red Terror imposed by Hungarian Bolsheviks who loved only members of a given social class, to radical Hungarian nationalists who loved only conformist members of their tribe, to Nazi collaborationists who wouldn’t settle for assimilating Jews but wished to kill them, finally to Stalinist stooges who ended up reviving tribal anti-Semitism. The exhaustion at the film’s end is palpable: In the same amount of time that separates us today from President Lyndon Johnson, the peoples of Central Europe went from the kindly Kaiser Franz Josef through Adolf Hitler to Josef Stalin. Call it Progress.

Apart from a heavily bureaucratic empire that spun its wheels preventing its dozens of ethnic minorities from cleansing each other’s villages, what was lost with the fall of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy? For one thing, we lost the last political link Western Christendom had with the heritage of the Holy Roman Empire. (Its crown stands today in the Imperial Treasury at the Hofburg, and for me it’s a civic relic.) Charlemagne’s co-creation with the pope of his day, that Empire had symbolized a number of principles we could do well remembering today: Principally, the Empire (and the other Christian monarchies that once acknowledged its authority) represented the lay counterpart to the papacy, a tangible sign that the State’s authority came not from mere popular opinion, or the whims of tyrants, but an unchangeable order of Being, rooted in divine revelation and natural law.

The job of protecting the liberty of the Church and enforcing (yes, enforcing) that Law fell not to the clergy but to laymen. The clergy were not a political party or a pressure group — but a separate Estate that often as not served as a counterbalance to the authority of the monarchy. No monarch was absolute under this system, but held his rights in tension with the traditional privileges of nobles, clergy, the citizens of free towns, and serfs who were guaranteed the security of their land. Until the Reformation destroyed the Church’s power to resist the whims of kings — who suddenly had the option of pulling their nation out of communion with the pope — no king would have had the power or authority to rule with anything like the monarchical power of a U.S. president. Of course, no medieval monarch wielded 25-40 percent of his subjects’ wealth, or had the power to draft their children for foreign wars. It took the rise of democratic legal theory, as Hans Herman Hoppe has pointed out, to convince people that the State was really just an extension of themselves: a nice way to coax folks into allowing the State ever increasing dominance over their lives.

A Christian monarchy, whatever its flaws, was at least constrained in its abuses of power by certain fundamental principles of natural and canon law; when these were violated, as often they were, the abuse was clear to all, and the monarchy often suffered. In extreme cases, kings could be deposed. Today, by contrast, priests in Germany receive their salaries from the State, collected in taxes from citizens who check the “Catholic” box. So much for the independence of the clergy.

The House of Austria ruled the last regime in Europe that bound itself by such traditional strictures, which took for granted that its family and social policies must pass muster in the Vatican. By contrast, in the racially segregated America of 1914, eugenicists led by Margaret Sanger were already gearing up to impose mandatory sterilization in a dozen U.S. states (as they would succeed in doing by 1930), while Prohibitionist clergymen and Klansmen (they worked together on this) were getting ready to close all the bars. As historian Richard Gamble has written, in 1914 the United States was the most “progressive” and secular government in the world — and by 1918, it was one of the most conservative. We didn’t shift; the spectrum did.

Dismantled by angry nationalists who set up tiny and often intolerant regimes that couldn’t defend themselves, nearly every inch of Franz-Josef’s realm would fall first into the hands of Adolf Hitler, then those of Josef Stalin. Today, these realms are largely (not wholly) secularized, exhausted perhaps by the enervating and brutal history they have suffered, interested largely in the calm and meaningless comfort offered by modern capitalism, rendered safer and even duller by the buffer of socialist insurance. The peoples who once thrilled to the agonies and ecstasies carved into the stone churches here in Vienna can now barely rouse the energy to reproduce themselves. Make war? Making love seems barely worth the tussle or the nappies. Over in America, we’re equally in love with peace and comfort — although we’ve a slightly higher (market-driven?) tolerance for risk, and hence a higher birthrate. For the moment.

Speaking of children brings me to the most haunting image I will take away from Austria. I spent a whole afternoon exploring the most beautiful Catholic church I have ever seen — including those in Rome — the Steinhof, built by Jugendstil architect Otto Wagner and designed by Kolomon Moser. An exquisite balance of modern, almost Art-Deco elements with the classical traditions of church architecture, it seems to me clear evidence that we could have built reverent modern places of worship, ones that don’t simply ape the past. And we still can. A little too modern for Kaiser Franz, the place was funded, the kindly tour guide told me in broken English, by the Viennese bourgeoisie. (Since my family only recently clawed its way into that social class, I felt a little surge of pride.) Apart from the stunning sanctuary, the most impressive element in the church is the series of stained-glass windows depicting the seven Spiritual and the seven Corporal Works of Mercy — each with a saint who embodied a given work. All this was especially moving given the function of the Steinhof, which served and serves as the chapel of Vienna’s mental hospital. (It wasn’t so easy getting a tour!) The church was made exquisite, the guide explained, intentionally to remind the patients that their society hadn’t abandoned them. Moser does more than Sig Freud can to reconcile God’s ways to man.

We see in the chapel the spirit of Franz Josef’s Austria, the pre-modern mythos that grants man a sacred place in a universe where he was created a little lower than the angels — and an emperor stands only in a different spot, with heavier burdens facing a harsher judgment than his subjects. No wonder Franz Josef slept on a narrow cot in an apartment that wouldn’t pass muster on New York’s Park Avenue, rose at 4 a.m. to work, and granted an audience to any subject who requested it. He knew that he faced a Judge who isn’t impressed by crowns.

As we left the church, I asked the guide about a plaque I’d seen but couldn’t quite ken, and her face grew suddenly solemn. “That is the next part of the tour.” She explained to me and the group the purpose of the Spiegelgrund Memorial. It stands in the part of the hospital once reserved for what we’d call “exceptional children,” those with mental or physical handicaps. While Austria was a Christian monarchy, such children were taught to busy themselves with crafts and educated as widely as their handicaps permitted. The soul of each, as Franz Josef would freely have admitted, was equal to the emperor’s. But in 1939, Austria didn’t have an emperor anymore. It dwelt under the democratically elected, hugely popular leader of a regime that justly called itself “socialist.” The ethos that prevailed was a weird mix of romanticism and cold utilitarian calculation, one which shouldn’t be too unfamiliar to us. It worried about the suffering of lebensunwertes Leben, or “life unworthy of life”–a phrase we might as well revive in our democratic country that aborts 90 percent of Down’s Syndrome children diagnosed in utero. So the Spiegelgrund was transformed from a rehabilitation center to one that specialized in experimentation. As the Holocaust memorial site Nizkor documents:

In Nazi Austria, parents were encouraged to leave their disabled children in the care of people like [Spiegelgrund director] Dr. Heinrich Gross. If the youngsters had been born with defects, wet their beds, or were deemed unsociable, the neurobiologist killed them and removed their brains for examination. …

Children were killed because they stuttered, had a harelip, had eyes too far apart. They died by injection or were left outdoors to freeze or were simply starved.

Dr. Gross saved the children’s brains for “research” (not on stem cells, we must hope). All this, a few hundred feet from the windows depicting the Works of Mercy. Of course, they’d been replaced by the works of Modernity.

We’re much more civilized about this sort of thing nowadays, as the guests at Dr. George Tiller’s secular canonization can testify. In true American fashion, our genocide is libertarian and voluntarist, enacted for profit and covered by insurance.

I will think of the children of the Spiegelgrund tomorrow, as I spend the morning in the Kapuzinkirche, where the Habsburg emperors are buried — and the Fraternity of St. Peter say a daily Latin Mass. As I pray the canon my ancestors prayed and venerate the emperors they revered, I will beg the good Lord for some respite from all the Progress we’ve enjoyed.

Blessed Karl I, ora pro nobis.

[Dr. John Zmirak‘s column appears every week at InsideCatholic.com.]

« Kampusquote »

Many college newspapers have their “overheard” sections, in which they give a selection of amusing or stupid things said around town. Our paper, Die Matie, has “Kampusquote”, the latest installment of which featured this nugget:

“Just make sure you don’t mix your white and black clothes!”

Alright, it sounds better in Afrikaans. Another favourite of mine was:

— Student upon learning that the head of the Music Conservatory is rotated amongst the conservatory’s departmental chairs

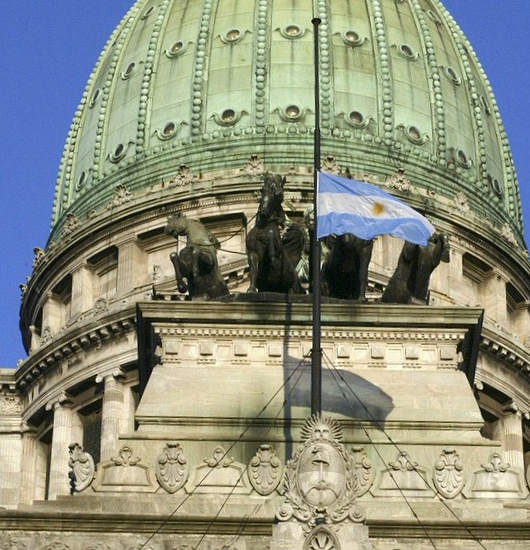

Argentina Mourns an Honest Man

RAÚL ALFONSÍN WAS often a stumbling, bumbling leader when he served as President of the Argentine Republic but, in a country of rampant corruption and abuse, his personal integrity was unassailable. It was probably for that reason that Argentines came on to the streets of Buenos Aires in April to mourn the loss of, certainly not the greatest statesman of the country’s history, but at least something simple: an honest man. For more on the late president, see my piece over at InsideCatholic.com. (more…)

The Dutch Flags of New York

The vexillological inheritance from our Netherlandic motherland

NEEDLESS TO SAY, New York owes a great deal to our Netherlandic founders, who imbued the city and land with much of its culture, eventually transformed (but not supplanted) by the overwhelming influence of the English who snuck a few warships into the harbour and knicked this land from the Hollanders. One of the many signs of New York’s Dutch history are the numerous flags which so obviously and proudly display this heritage. Here are just a few simple notes about a few of these flags.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories