World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

St. Zita?

Church Opens Investigation into Sanctity of Zita of Bourbon-Parma, Wife of Blessed Charles and Last Empress of Austria-Hungary

It was announced recently that Mgr. Yves Le Saux, Bishop of Le Mans in the traditional province of Maine (Pays de la Loire), France has opened the cause for the beatification of Zita of Bourbon-Parma, the long-lived wife of Blessed Emperor Charles of Austria. Charles, the last (to date) Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary, and King of Bohemia (&c.), died in exile in Madiera in 1922, aged just thirty-four years. Zita Maria delle Grazie Adelgonda Micaela Raffaela Gabriella Giuseppina Antonia Luisa Agnese de Bourbon-Parma, meanwhile, was born in Tuscany in 1892 and lived a long life, giving up the ghost in March 1989, and interred in the Capuchin vault in Vienna following a funeral of imperial dignity.

“The process was opened in Le Mans,” Gregor Kollmorgen of TNLM reports, “and not in the Swiss diocese of Chur, where the Empress died twenty years ago in 1989 in Zizers, with the consent of Msgr. Huonder, the Bishop of Chur, and the permission of the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints, because within the diocese of Le Mans is situated the Abbey of Solesmes, well known to NLM readers for its leading rôle in the early liturgical movement in the nineteenth century, especially regarding Gregorian chant, and which was the spiritual center of the Servant of God Zita, her home among her many exiles.”

Zita’s relationship with Solesmes dates back to 1909 when she first visited its sister-abbey of St. Cecilia on the Isle of Wight in England. She became an oblate of the Abbey of Solesmes itself in 1926. Her daily life after the exile & death of her saintly husband included the Rosary, hearing multiple daily masses, and praying part of the Divine Office. (more…)

The Internal Exile of the Saar

At the beginning of Hitler’s rule, many patriotic German anti-Hitlerites fled to the Saarland, which was Germany but still under French occupation. In a bizarre state of internal exile, anti-Nazi publications, be they Christian, Nationalist, Communist, or Jewish flourished for a very brief period. One of these journals was Das Reich, founded by Hubertus Prinz zu Löwenstein, who (if I recall my personal studies from St Andrews years properly) was a bit of a rogue in his own way, sympathizing with the Red forces during the Spanish Civil War.

A plebiscite on rejoining the Saarland with Germany proper had been scheduled before Hitler’s rise to power (just like the lamentable award of the 1936 Olympics to Berlin, though they turned out to be some of the most influential and well-run games to date) and, while the inhabitants were no keen Hitlerites, they had naturally tired of French occupation and duly voted to kick the French out. Right result, but very poor timing.

The anti-Hitlerites had to flee further, to Paris (where Pariser Tageblatt and later Pariser Tageszeitung were founded), London, and New York. German Jews sometimes fled as far as Shanghai where the English-language Shanghai Jewish Chronicle began a German edition in response to the influx. (There are some interesting stories about Shanghai Jews, and of course the famous newspaper-owning family of Jewish converts to Catholicism in Shanghai, but they’ll have to wait for another day).

Baron Bossom’s Bridge

The Unbuilt ‘Victory Bridge’ Crossing the Hudson River at Manhattan

After the victory of America and her “co-belligerents” in the First World War, a temporary victory arch was erected out of wood and plaster to welcome the troops home from Europe. After the arch was dismantled, however, discussions soon arose on how to permanently commemorate the war dead of New York, with a surprising variety of suggestions made. A beautiful water gate for Battery Park was suggested, with a classical arch flanked by Bernini-like curved colonnades, so that a suitable place existed to welcome important dignitaries and visitors to New York. (Little did they know how soon the airlines would replace the ocean lines). Another proposal was for a giant memorial hall located at the site of a shuttered hotel across from Grand Central Terminal, while others suggested a bell tower.

An entirely different proposal, however, was made by the New York architect Alfred C. Bossom (later ennobled as Baron Bossom of Maidstone). Bossom, an Old Carthusian, was an Englishman by birth and eventually returned to his native land, where (in 1953) he gave away the future prime minister Margaret Roberts at her marriage to Denis Thatcher. He himself served in parliament from 1931 until 1959, excepting his wartime Home Guard service. Jokes were often made about his surname resembling both “bottom” and “bosom”. Upon being introduced to Bossom, Churchill jested “Who is this man whose name means neither one thing nor the other?” (more…)

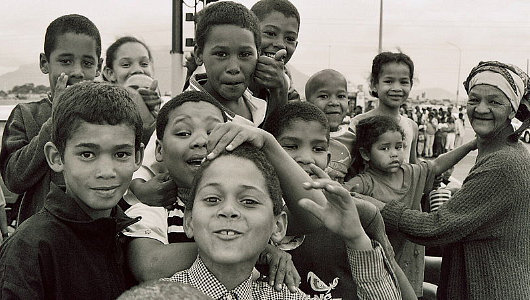

Simon Kuper: Coloured Identity is an “Artificial, Ugly Leftover from Apartheid”

Honestly, a man like Simon Kuper should know better. The sports columnist for the Financial Times was born in Uganda, raised in the Netherlands, but both his parents are South African. In a recent article (“Apartheid casts its long dark shadow on the game”, Financial Times, 4 December 2009), Kuper discusses the racial divisions in South Africa and how they are reflected in terms of sport: White South Africans tend to gravitate towards rugby and cricket, whereas their Black compatriots overwhelmingly prefer soccer.

There exists in South Africa, however, a very large community known as the Coloureds, who are of mixed ethnic descent. Mr. Kuper, in his article, implies that they exist merely thanks to “the racial classifications of apartheid”, as if there were no Coloured people before 1948. Furthermore, he explicitly calls the difference between Coloured and Black South Africans “artificial” and an “ugly leftover from apartheid”. This is simple ignorance. He also refuses to use the word Coloured without quotation-marks, though one suspects he does not refer to Basques as “Basques”, Scots as “Scots”, Maoris as “Maoris” or so on and so forth.

The Coloureds (or kleurlinge or bruinmense in Afrikaans) are a very distinct people who form the majority of the population in the Western Cape and Northern Cape provinces. They are over four million in number and, while their distinct identity only came about after the intermarriage (and interbreeding) between the Dutch and natives after 1652, they include the genetic descendants of the old Khoisan tribes, the first people of the Cape. The Coloureds have been hugely influential in the history of the Afrikaans language, which is spoken by nine out of ten Coloured people. Just as the majority of Coloureds speak Afrikaans, the majority of Afrikaans-speakers are Coloured, not Afrikaner.

In short, Coloured people are real. They exist, and are a distinct, historical, vibrant, active culture. It is true that Coloureds are sometimes lobbed together with Zulus, Xhosa, Tswana, and others as “Black” but if one is forced to pigeon-hole them in Black-and-White terms it would be much more accurate to say either that they are both or that they are neither. Indeed, Coloureds, like Indian and White South Africans, have often faced discrimination at the hands of the ruling party, which is multi-ethnic in composition but dominated by Xhosas & Zulus in practice. The differences between Blacks and Coloureds are no more “artificial” than those between English and Irish. Mr. Kuper may want to ignore those differences (ergo, erase Coloured identity) but I say vive la différence.

Baroness Scotland

Ironically, Baroness Scotland is the Attorney-General for England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, but not Scotland.

The Diogenes Club

“There are many men in London, you know, who, some from shyness, some from misanthropy, have no wish for the company of their fellows,” says Sherlock Holmes in The Greek Interpreter. “Yet they are not averse to comfortable chairs and the latest periodicals. It is for the convenience of these that the Diogenes Club was started, and it now contains the most unsociable and unclubable men in town. No member is permitted to take the least notice of any other one. Save in the Stranger’s Room, no talking is, under any circumstances, allowed, and three offences, if brought to the notice of the committee, render the talker liable to expulsion. My brother was one of the founders, and I have myself found it a very soothing atmosphere.” (more…)

Canada’s Bastion of Catholicism

Our Lady Seat of Wisdom in Barry’s Bay, Ontario

Many of our readers doubtless enjoy this blog for its unabashed defence of the glories of Christendom, all too many of which have passed into the pages of history. But highlighting those glimmers of hope that yet exist is another worthwhile task. The renaissance of Catholic higher education in the United States proceeds apace, with new institutions like Thomas Aquinas College, Christendom College, and such leading the way, while others retake the older Catholic universities from the inside. These places of learning have been gathered together in the Newman Guide to Choosing a Catholic Colleges, the guide to Catholic colleges for Catholics who actually want their Catholic colleges to be Catholic. An almost ridiculous thing to say, but such is the state of modern higher education.

While the Guide‘s purview was initially limited to the United States, Canada’s Our Lady Seat of Wisdom Academy — a college in Ontario offering one-, two-, and three-year Catholic liberal arts programs of study — began to get such rave reviews that, as Joseph Esposito, editor of the guide, put it, “we were so impressed by Our Lady Seat of Wisdom that we felt compelled to include it as well. The academy has accomplished much in a short period of time, and we look forward to it being an influential force in Catholic higher education.” In particular, the Academy has excelled at introducing home-schooled students to a more formal style of education to ease their transition into higher studies.

That, as the Newman Guide puts it, Our Lady Seat of Wisdom “provides a wonderful curriculum at a breathtakingly low cost” to students and the families supporting them is admirable, but the word on the street is that current economic woes of the world have landed the Academy in a bit of a financial bad-patch. The folks in charge are taking the proper steps of reducing pay and seeking out other savings, but I hope & pray that Catholics will be able to keep afloat this splendid institution which is utterly loyal to the Magisterium and devoted to educating the next generation of America’s and Canada’s Catholics.

Those interested in helping out can find out how to do so here. Americans in particular might take advantage of the non-profit status of the U.S.-based Friends of Our Lady Seat of Wisdom Academy. There is also a PayPal button in the right-hand column on the college’s main page. Having been on the receiving end of generosity myself, I know that every little bit helps.

Giving something to help this institution keep going is an act in keeping with the spirit of this Advent season.

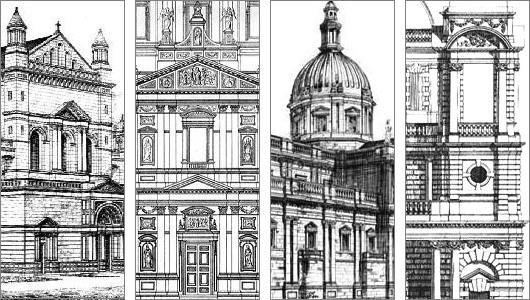

Brompton Oratory as It Might Have Been

Failed Entries of the 1878 London Oratory Architectural Competition

ARCHITECTURAL COMPETITIONS have always fascinated me because they give us the opportunity to glance at multiple executions for a single concept, to see different minds solve a “problem” with their own particular formulas and theorems. The designs of many of the world’s prominent buildings were chosen by competition, perhaps the Palace of Westminster — Britain’s Houses of Parliament — is most famous among them. When the Hungarian Parliament held a competition to design a grand palace to house the body, it found the top three prize designs so compelling that it built the first-prize design as parliament and the second and third places as government ministries nearby. To my surprise, I have only ever come across one book which adequately surveyed the subject of competitive architecture, Hilde de Haan’s Architects in Competition: International Architectural Competitions of the Last 200 Years. Most of the contests covered in the book are, naturally, for government buildings of national importance — private clients usually have a very firm idea of what they want and choose an architect accordingly.

One building not mentioned in the book but nonetheless very dear to me (and no doubt to many readers of this little corner of the web) is the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary of the Congregation of the London Oratory, more popularly known to friend and foe alike as the Brompton Oratory. It was the first church in Britain in which I ever heard mass, the summer after kindergarten when I was still but a tiny, blond-haired whippersnapper, in the midst of my first visit ever to the Old World, and the Oratory made quite a strong impression upon my young mind. It is usually one of my very first ports of call whenever I am in the capital, and I once even managed to slip in having just arrived at Heathrow while making my way to King’s Cross and the train to Scotland.

The Brompton Oratory is known for having good priests, traditional liturgy, and beautiful architecture. The final design was by one Herbert Gribble, but there was quite a bit of to-ing and fro-ing before Gribble was selected. The temporary church which had been erected on the site had been condemned by one critic as “almost contemptible” in its exterior design. In 1874, the Congregation of the Oratory (which is to say, the priests) put out an appeal for funds towards the construction of a permanent church. The 15th Duke of Norfolk obliged with £20,000 to get the ball rolling, and the next year a design by F. W. Moody and James Fergusson was agreed upon in principle. But the Reverend Fathers soon began to get creative and hatch ideas and contact other architects and very soon it was claimed that there were as many counter-proposals as there were priests of the Oratory, and perhaps more. A pack of clerics supported a suggested design by Herbert Gribble, but no accord could be reached among the Congregation as a whole.

In January 1878, then, it was announced that a competition would take place to decide the design of the permanent church of the London Oratorians. First prize was £200, with £75 for the runner-up. All entries had to meet the certain requirements drawn up by the Congregation. The style was to be “that of the Italian Renaissance”. The sanctuary, at least sixty feet deep, must be “the most important part of the Church. … Especially the altar and tabernacle should stand out as visibly the great object of the whole Church.” The minimum width of the nave was fifty feet, and maximum length 175 feet. Subsidiary chapels must be “distinct chambers”, not merely side altars. One aspect not mentioned was the projected execution costs of the designs — “an omission criticized by architectural journalists and disgruntled competitors,” the London Survey tells us, “whose designs called for expenditure ranging from £35,000 to £200,000”.

Over thirty entries were submitted to the competition, and Alfred Waterhouse was commissioned by the Fathers to provide comment on the submissions. Significantly, George Gilbert Scott, Jr. submitted a design, though I haven’t been able to get my hands on any depictions of it. Waterhouse praised it as “of no ordinary merit. … I feel that it is impossible to speak too highly of its beauty, its quiet dignity, its absence of all vulgarity and its concentration of effect around the high altar.” (more…)

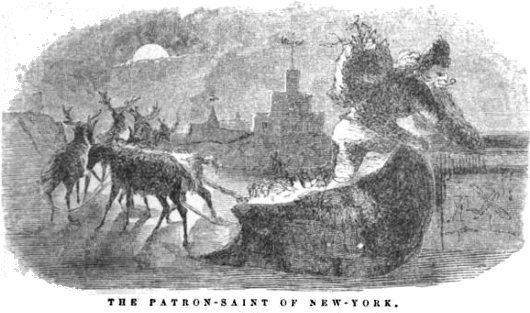

‘The Feast of St Nicholas’, Jan Steen

1665-68, Rijksmuseum

Patron of the Knickerbockers, pray for us

Die Nuwe Kanselier

Johann Rupert is die 14de seremoniële hoof van die Universiteit van Stellenbosch

Mnr Johann Rupert, ’n afgesonderde sakeman en die seun van een van Suid-Afrika se bekendste entrepreneurs, is om die nuwe kanselier van Stellenbosch Universiteit. Dit is baie goeie nuus vir die universiteit en vir die taal, soos is mnr Rupert ’n vurige verdediger van Afrikaans. Waneer die Britse ontwerp- en leefstyltydskrif Wallpaper beskryf die taal soos “the ugliest language in the world”, Rupert — voorsitter van die Switserse luukse goedere conglomeraat Richemont — het alle advertensies vir sy groep se merken van die tydskrif verwyder. Die tydskrif het miljoene ponde in inkomste verloor, uit prominente Richemont maatskaapye soos Cartier (juweliers), Vacheron Constantin (horlosiemakers), Montblonc (penne), en Alfred Dunhill. Die Suid-Afrikaanse Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns, die AKTV, en ander kulturele organisasies het Rupert se optrede geondersteun.

Agtergrond van die oudste seun

Johann is die seun van die wyle entrepreneur en omgewingsbewaarder Anton Rupert, en Stellenbosch is sy tuisdorp. Hy het ook studeer ekonomie aan Stellenbosch Universiteit, wat verleen hom ‘n eredoktorsgraad in 2004. In sy vroeë jare in die sakewêreld, mnr Rupert het vir Lazard Frères in New York vir drie jaar gewerk, maar hy terug na Suid-Afrika in 1979 om Rand Merchant Bank te oprig. In 1988, Rupert stig die Compagnie Financière Richemont, en hy is nog steeds voorsitter. Ten spyte van sy rykdom, hy die soeklig vermy, en die Financial Times noem hom “reclusive”. Die selfde koerant bynaam hom “Rupert the Bear” vir sy korrek pessimistiese ekonomiese voorspellings.

’n Sterk kampvegter vir Afrikaans

Die Burger, die Kaap se koerant van rekord, sê: “Hoewel die pos van kanselier grootliks seremonieel is, kan ’n mens verwag dat iemand van Rupert se statuur en ywer ook hier sy rol op ’n vars en innoverende wyse sal vervul.”

“Sy openbare rekord as deeglike sakeman en uitsonderlike entrepreneur spreek immers vanself,” sê die koerant. “Rupert se uitmuntende sakeleierskap en visie het hom reeds verskeie toekennings op internasionale en nasionale vlak besorg. Hieronder tel Mees Invloedryke Leier in Suid-Afrika (drie keer), een van die internasionale leiers van die toekoms en handevol ander toekennings.”

“Die Burger het natuurlik sélf bande met Rupert. Hy is ’n vorige sakeleier van die jaar van dié koerant en en die Kaapstadse Sakekamer. Buite die sake-arena is Rupert ’n sterk kampvegter vir Afrikaans en is hy nou betrokke by sportontwikkeling.”

“Die mantel van kanselier val op hom in ’n tyd van besondere uitdagings aan tersiêre inrigtings. Maties self worstel met die uitdagings van transformasie en veral met die kwessie van Afrikaans as onderrigmedium. Daar kan verwag word dat Rupert ook by die US ’n sterk en rigtinggewende rol sal speel.”

NOTA VIR AFRIKAANS-SPREKENDES: Ek hoop dat u my arme grammatika sal verskoning. Dit is nie my moedertaal nie, maar ek hou van die taal.

The Sovereign Scotch Order of Whisky

The Order of Malta recently paired up with Scotland’s own Adelphi Distillery to produce two variants of Scotch, proceeds from the sale of which support the Order’s worldwide charitable efforts. Adelphi produced a single malt called ‘The Grand Master’ and a blend named ‘Torphichen’, after Torphicen Preceptory, the headquarters of the Order in Scotland until the Reformation.

The last Preceptor of the Order in Scotland lamentably converted to Calvinism, surrendered the Order’s lands to the Crown (which were then re-granted to him specifically), and received the title Lord Torphichen (pronounced Tor-fikken).

Unlike most peerages, that of Lord Torphichen can be inherited by any assigned heir. In practice, it has descended through the Chiefs of Clan Sandilands, but in principle the holder could decide to designate any old Tom, Dick, or Harry as the next Lord Torphichen. (more…)

Clueless blogger: Alistair Bruce

Over at Sky News, we read the following from blogger Alistair Bruce:

Or… perhaps because it was November 30… the Feast of Saint Andrew… Scotland’s national day? It strikes me, however, that Google UK’s little image of Edinburgh Castle is as astonishingly poor one. They should’ve commissioned Iain McIntosh, who designed the Edinburgh Castle logo of the Edinburgh Evening News (at right). Mr. McIntosh also does the splendid illustrations for the 44 Scotland Street series, not to mention the Professor von Igelfeld Entertainments, depicting the trials and tribulations of poor Professor Dr Moritz-Maria von Igelfeld of the Institute of Romance Philology at Regensburg.

Or… perhaps because it was November 30… the Feast of Saint Andrew… Scotland’s national day? It strikes me, however, that Google UK’s little image of Edinburgh Castle is as astonishingly poor one. They should’ve commissioned Iain McIntosh, who designed the Edinburgh Castle logo of the Edinburgh Evening News (at right). Mr. McIntosh also does the splendid illustrations for the 44 Scotland Street series, not to mention the Professor von Igelfeld Entertainments, depicting the trials and tribulations of poor Professor Dr Moritz-Maria von Igelfeld of the Institute of Romance Philology at Regensburg.

The Messiah in the Sportpalast

The following feuilleton was written before Hitler became the master of Germany. The scene is the Berlin Sportpalast, the largest indoor arena in the world when it opened in 1910 and, at this time, the setting for the rallies of the various political parties vying for control of the Weimar Republic.

On the night of the Horst Wessel commemoration Hitler speaks in the Berlin Sportpalast. People who have neither seen nor heard him will perhaps never fully understand the significance of the profoundly ominous mind-set that has developed in Germany since the war. The reality — Hitler’s version of reality and its full implications — goes far beyond anything you might read in the newspapers, or imagine. Here is that reality, drawn from the life. (more…)

Tibetan Word of the Day

Our Tibetan word of the day is Rum-yül, the language’s traditional word for “Europe”.

The word literally means “Rome-land”, giving a certain Bellocian tone to the Tibetan language — it was Belloc, after all, who said “Europe is the Faith; the Faith is Europe”.

Notes of the Netherlandic Church II

Archbishop Eijk chooses tradition-friendly priest as his cathedral rector

Fr. Harry Van der Vegt

The Archbishop of Utrecht & Primate of the Netherlands, Wim Eijk, has chosen a priest well-known for friendliness to traditional Catholics as the rector of his own cathedral. It was announced recently that Father Harry Van der Vegt is to be appointed rector of the Cathedral Church of St. Catherine in Utrecht, effective January 1, 2010. The priest will also be pastor of the Augustinuskerk and of St. Willibrord’s (which was the subject of the last Dutch church update).

Erik van Goor, of the Dutch periodical Bitterlemon, describes Fr. Van der Vegt as a “quiet but sturdy peasant’s son”. In the face of opposition from Modernist clergy and laity, Fr. Van der Vegt has been known to keep his cool, van Goor says. “Without making a political game of it, without showing any sign of reduced loyalty to the Church as it exists in the Netherlands, he remained quietly loyal to the tradition of the Church.”

“The appointment of Van der Vegt is actually a bit of a surprise”, notes one Dutch blogger, “because Archbishop Eijk is not really known as a major supporter of the old rite.” His Excellency was nonetheless responsible for normalizing the situation of the traditionalists of St. Willibrord’s Church in his diocese, mentioned previously.

Fr. Van der Vegt is currently serving the traditional faithful of Deventer in the province of Overijssel, and his new appointment will likely leave those people without a traditional mass for the time being. However, as Fr. Van der Vegt will be assuming control of St. Willibrord’s, the two FSSP priests currently there will probably be reassigned. The two currently travel all across the Low Countries, offering masses in Amsterdam, Bruges, Rotterdam, and elsewhere.

Parishioners at St. Willibrord’s, meanwhile, hope the new priest will say the extraordinary form at a more advantageous hour; it is currently said each Sunday at 5:30 in the evening.

Foundation ‘Ecclesia Dei’ Delft Releases 2009 Report

The Foundation ‘Ecclesia Dei’ Delft has released its latest report on the state of tradition in the Netherlandic church. ‘Ecclesia Dei’ is a group of Catholic faithful attached to the traditional liturgy as codified in the 1962 missal, and exists for the promotion of Catholic orthodoxy and specifically the liturgical tradition of the Church. In gauging the response to Benedict XVI’s motu proprio Summorum Pontificium, the report finds that “the Dutch Bishops Conference did not define a common policy concerning the implementation of the motu proprio.” The general attitude of the bishops is described as one of extreme passivity, “discouraging requests, ignoring the traditional liturgy, and keeping the faithful in ignorance of the motu proprio by a lack of information combined with disinformation about the traditional Latin liturgy.”

The report posits that bishops are primarily “afraid of the opposition by the modernist-infected priests and/or parish boards.” Many ordinary orthodox Catholics in the Netherlands are disillusioned with the strident Modernism that has infected much of the local church, and the bishops are said to fear “polemics” and “discord” even though, the report states, “they have not undertaken any measures to solve these problems for many years”.

On the teaching of the traditional liturgy in Dutch seminaries, the report confirms that instruction about the extraordinary form is almost nonexistent.

“However, since March 2009 and against the opposition of a number of priestly staff members at the seminary of St. Jan in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, a course about the theology of the traditional Latin liturgy has been given, but only because some of the seminarians claimed to have the right to it and showed a letter from the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei.”

“As a result, 8 of the 12 seminarians now attend a private traditional Latin Mass three days a week at that seminary, despite the opposition.”

“In some diocese the situation has been improved in the first year of the motu proprio only by the initiatives of individual, relatively young priests.”

Some priests have attended German-organised training sessions, while others have received instruction from the FSSP priests in Amsterdam.

“Most of these priests are celebrating the traditional Latin liturgy in private and some even weekly in public now.”

As for the news of the specific dioceses of the Netherlands, much has already been written about the primatial see of Utrecht. In the Diocese of Haarlem-Amsterdam, Bishop Punt is prepared to grant FSSP a personal parish, from which the priests can work all over his diocese. Talks are ongoing. In other dioceses, however, foot-dragging, lip service, or ignorance of requests have been the norm.

The Parliament of the Venerable Island

Geoffrey Bawa’s Sri Lankan Parliament at Kotte

CEYLON IS AN ancient island whose history spans the epochs of human existence: palaeontologists estimate it has been inhabited for over 34,000 years. A series of ancient and medieval native kingdoms have ruled this island over the centuries before foreigners from abroad decided to enter the game. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to stake a claim here, followed by the Dutch Republic. And, yes, as with almost every place of intrigue and tradition, even Ceylon belonged to the Hapsburgs at one point: from 1580 to 1640. Native kingdoms persisted nonetheless, even while European powers bickered over their own portions of the island.

It was in 1815 that the Chiefs of the Kandyan Kingdom agreed to depose their own monarch, Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, and place George III of the House of Hanover on the throne. Ceylon was united at last, and — after the end of the Kandyan Wars — the island enjoyed relative peace and prosperity during one-hundred-and-thirty-three years of British rule.

In 1948, the British granted independence to the Dominion of Ceylon. The island continued as an independent constitutional monarchy for much longer than its neighbours India and Pakistan. The rudiments of a two-party system emerged, with the United National Party bringing together the conservative, traditional element in political society, while the Freedom Party advocated non-revolutionary socialism.

The population of Ceylon, however, are a complete hodgepodge of ethnicities. The largest group are the Sinhalese, a Buddhist people constituting over 70% of the population. But at the northern end of the island, the Tamil people were dominant, even though these were split between “Ceylonian” Tamils native to the island and “Indian” or “Plantation” Tamils brought during British rule to work the large plantations. Then there are the Moors, a multiracial Muslim community of primarily Arab and Malay descent. And, of course, there are the famous Burgher people, descendants of the island’s Portuguese, Dutch, and English mixed with Sinhalese, Tamil, and Creole.

Democratically elected politicans replaced English (the intercommunal lingua franca) with Sinhala (the language of the Sinhalese majority) as the official language, abolished the Senate, severed appeal to the Privy Council and, in 1970, abolished the monarchy. The Dominion of Ceylon was renamed the Republic of Sri Lanka — the name literally means “Venerable Island”. Left-wing nationalists continually stoked tensions with the country’s conservatives, traditional elite, and minorities, and provoked right-wing reactions. Aside from the left-right divide, Tamil extremists began an anti-Sinhalese terror campaign that increased the oppression of the Tamil people and strengthened the country’s divisions. In short, it all became a mess. (more…)

Universitas Carolina Pragensis

The Charles University of Prague

Prague’s university, the Universitas Carolina, was founded in 1347 and this is the first university of the Germans — a nation with a long (if varied) intellectual tradition. In a fashion similar to the medieval university of Paris, the Charles University was divided into “nations”: the Bavarians, the Bohemians, the Poles, and the Saxons. The splendid cosmopolitanism of Christendom was threatened by the challenge of nationalism as early as the 1400s, when the Decree of Kuttenberg stoked ethnic tensions by granting the masters of the Bohemian “nation” at the University three votes to the one vote to be shared amongst the Bavarians, Poles, and Saxons. All of this was provoked by various political power plays during the Western Schism, and the Decree resulted in an exodus of German professors and students to other universities, and indeed inspired the foundation of the university at Leipzig. More lamentable was the election, soon after, of the heretic Jan Hus as rector of the Bohemian-dominated university. No good came from this, but after the fall of the Hussites, order was restored.

In the following centuries the university underwent numerous changes. A new academy, the Clementinum, was founded in 1562. The Jesuits were given control in 1622, and twenty years later Ferdinand III merged the two centers of learning to form the Charles-Ferdinand University. In 1784, German replaced Latin as the language of instruction, and in 1791 Leopold II established a chair of Czech language and literature. By the 1860s, the royal city of Prague no longer had a German-speaking majority, and by then Czech had joined German as a medium of learning. Lamentably, the government decided to split Prague’s university in two on lingual lines: the Royal & Imperial German Charles-Ferdinand University, and the Royal & Imperial Czech Charles-Ferdinand University.

The German university experienced a brief heyday just before the First World War, but America’s entry into the conflict spelt doom not only for Catholic Europe as a whole, but specifically for any peoples who found themselves suddenly a member of an “ethnic minority”, no matter if they had dwelled there for centuries. The new Czechoslovak republic passed laws favouring the Czech University over the German University. With just over 50,000 Germans living in Prague after the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the German University considered moving to Reichenberg (Cz., Liberec) in northern Bohemia, the central city to Czechoslovakia’s German population of some millions, but the academic leadership demurred.

After the 1939 invasion and occupation of Czechoslovakia, the Czech University was closed by the Nazis, who purported the close was temporary, but it remained shut until after the Soviet conquest of Prague in May 1945. The new Soviet-backed Czechoslovak authorities began the immediate ethnic cleansing of all Germans from their territory, irrespective of whether they had actively abetted the Nazis, resisted them, or remained inactive. The German University collapsed, but its remnants fled to Munich, where the Collegium Carolina continues today as a German-language institute for higher studies in Bohemian & Czech culture.

While the Czech University reopened — called simply the Univerzita Karlova v Praze, or Charles University of Prague — its freedom was short-lived as the Communists began their takeover of the Czechoslovak government and society. With the relaxation of restrictions during the 1980s, faculty and students began to voice their dissent from the socialist system, and many participated in the Velvet Revolution that ended political communism in Czechoslovakia. Today, the Charles University is widely recognised as the preeminent academic institution of the Czech Republic.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories