World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

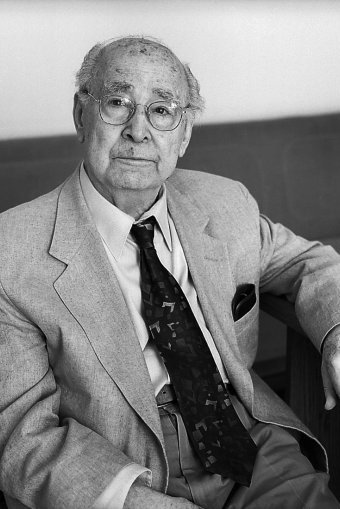

Thomas Molnar, 1921–2010

The Catholic philosopher and historian Thomas Molnar died last week in Virginia at eighty-nine years of age, just six days short of reaching his ninetieth year. Born Molnár Tamás in Budapest in 1921, the only son of Sandor and Aranka, Molnar was schooled across the Romanian border in the town of Nagyvárad (Rom.: Oradea) in the Körösvidék, a region often included in Transylvania and an integral part of Hungary until the Treaty of Trianon cleaved it a year before. In 1940 he moved to Belgium to begin his higher education in French, and as a leader in the Catholic student movement he was interned by the German occupiers and sent to Dachau. With the end of hostilities, he returned to Brussels before arriving home in Budapest to witness the gradual Communist takeover of Hungary.

and historian Thomas Molnar died last week in Virginia at eighty-nine years of age, just six days short of reaching his ninetieth year. Born Molnár Tamás in Budapest in 1921, the only son of Sandor and Aranka, Molnar was schooled across the Romanian border in the town of Nagyvárad (Rom.: Oradea) in the Körösvidék, a region often included in Transylvania and an integral part of Hungary until the Treaty of Trianon cleaved it a year before. In 1940 he moved to Belgium to begin his higher education in French, and as a leader in the Catholic student movement he was interned by the German occupiers and sent to Dachau. With the end of hostilities, he returned to Brussels before arriving home in Budapest to witness the gradual Communist takeover of Hungary.

Molnar left for the United States, where he earned his Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1950. He frequently contributed to the pages of National Review after its foundation by William F. Buckley in 1955, and his periodic writings were often found in Monde et Vie, Commonweal, Modern Age, Triumph, and other journals. From 1957 to 1967 he taught French & World Literature at Brooklyn College before moving on to become Professor of European Intellectual History at Long Island University. In 1969 he was a visiting professor at Potchefstroom University in the Transvaal. In 1983 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Mendoza in Argentina while he was a guest professor at Yale. After the fall of the Communist regime in Hungary, he taught at the University of Budapest and at the Catholic University (PPKE). In 1995 he was elevated to the Hungarian Academy of Arts.

While his first book, Bernanos: his political thought and prophecy (1960), was well-received, it was Molnar’s second published work that was arguably his best known. The Decline of the Intellectual (1961) was, in Molnar’s own words, “greeted favorably by conservatives, with respectful puzzlement by the left, and was dismissed by the liberal progressives.” Gallimard began discussions to print a French translation as part of its prominent Idées series, before the publisher’s in-house Marxist Dionys Mascolo vetoed it for its treatment of Marxism as a utopian ideology. The celebrated & notorious Soviet spy Alger Hiss complimented it in a Village Voice review, but Molnar noted that The Decline of the Intellectual‘s harshest criticism came from liberal Catholic circles. “Obviously,” he wrote, “in that moment’s intellectual climate, they would have preferred a breathless outpouring of Teilhardian enthusiasm.”

The book argued, from a deeply conservative European mindset, that the rise of the intelligentsia during the nineteenth century was tied to its capacity as an agent of bourgeois social change. As the intellectual class increasingly shaped the more democratic, more egalitarian (indeed, more bourgeois) world around it, the intelligentsia’s vitality, so tied to its capability to enact social change (Molnar argued), became self-destructive. The “decline” set in as the intelligentsia searched for alternative methods of social redemption in increasingly extreme fashions (such as nationalism, socialism, communism, fascism, &c.) and led to the intellectuals allying themselves with ideology, which is the surest killer of genuine intellectual and philosophical speculation.

The same year Molnar’s The Future of Education was published with a foreword by Russell Kirk, whose study of American conservative thinkers, The Conservative Mind, was admired by Molnar. Among the many works that followed were Utopia, the perennial heresy (1967), The Counter-Revolution (1969), Nationalism in the Space Age (1971), L’éclipse du sacré : discours et réponses in 1986 with Alain Benoist, and the following year The Pagan Temptation refuting Benoist’s neo-paganism, The Church, Pilgrim of Centuries (1990), and in 1996 Archetypes of Thought and Return to Philosophy. From then until his death, the remainder of his new books have been published in his native Hungarian language.

Molnar and his work have become sadly neglected for the very reasons he detailed in his major work: the overwhelming triumph of ideology over the intellectual sphere. While Russell Kirk defined conservatism as the absence of ideology, modern conservatism in America has become almost completely enveloped by ideology, and the Molnar’s deep, traditional way of thinking — influenced to a certain extent by de Maistre and Maurras — is now met more by silence and ignorance than by direct condemnation.

The triumph of ideology (be it on the left or the right) was aided and abetted, Molnar argued, by a culture dominated by media and telecommunications. “Around 1960,” Professor Molnar wrote later in his life, “the power of the media was not yet what it is today.”

Hardly anybody suspected then that the media would soon become more than a new Ceasar, indeed a demiurge creating its own world, the events therein, the prefabricated comments, countercomments—and silence. … The more I saw of universities and campuses, publishers and journals, newspapers and television, the creation of public opinion, of policies and their outcome, the less I believed in the existence of the freedom of expression where this really mattered for the intellectual/professional establishment. For the time being, I saw more of it in Europe, anyway, than in America: over there, institutions still stood guard over certain freedoms and the conflict of ideas was genuine; over here the democratic consensus swept aside those who objected, and banalized their arguments. The difference became minimal in the course of decades.

Needless to say, the world of American conservatism has been silent in responding to the death of Professor Molnar.

Ideology’s enforced forgetfulness aside, Molnar’s native Hungary renewed its appreciation for him just before his death: last year the Sapientia theological college organised the first conference devoted to his works, which was well-attended and much commented-upon in the Hungarian press. Besides his serious corpus of works, Molnar is survived by his wife Ildiko, his son Eric, his stepson Dr. John Nestler, and his seven grandchildren.

Requiescat in pace.

Previously: Understanding the Revolution

Elsewhere: Professor Thomas Molnar, In Memoriam

Interesting Things Elsewhere

This determined Celt is gunning for Thabo

Kevin Bloom | The Daily Maverick

Ireland’s  Paul O’Sullivan took over as head of security at South Africa’s airport authority in 2001, and discovered something was wrong from the start: why didn’t the policeman on duty want to take a statement about the attempted theft of his baggage? Since then, his life has been a series of bizarre events leading him ever deeper into the most complex criminal network of the post-apartheid era, including the recent the trial and conviction of former national police chief Jackie Selebi. But O’Sullivan’s determined quest to expose crookedness isn’t over yet, and he now has former president Thabo Mbeki in his sights. read more

Paul O’Sullivan took over as head of security at South Africa’s airport authority in 2001, and discovered something was wrong from the start: why didn’t the policeman on duty want to take a statement about the attempted theft of his baggage? Since then, his life has been a series of bizarre events leading him ever deeper into the most complex criminal network of the post-apartheid era, including the recent the trial and conviction of former national police chief Jackie Selebi. But O’Sullivan’s determined quest to expose crookedness isn’t over yet, and he now has former president Thabo Mbeki in his sights. read more

The apparatus of state will simply ignore the government

‘Inspector Gadget’ | Police Inspector Blog

Police across England were told by the responsible minister of the democratically elected government that they must not chase performance targets any longer. “I can also announce today that I am also scrapping the confidence target,” said the Home Secretary, Theresa May, “and the policing pledge with immediate effect”. But the ‘senior management team’ of the West Yorkshire Police have stated they will go on no matter what the government says. read more

Has Christian Democracy reached a dead end?

Jan-Werner Mueller | Guardian.co.uk

The commentator completes a brief survey of the struggles of Christian Democracy in Germany and Europe today. The French leader Georges Bidault claimed that Christian Democracy meant “to govern in the centre, and pursue, by the methods of the right, the policies of the left”. But Christian Democracy’s brief French moment in the 1950s didn’t survive the return of de Gaulle, and Christian Democratic parties on the continent today face an existential crisis. read more

Also: Monsignor Ignacio Barreiro’s talk at the Roman Forum’s 2010 Summer Symposium, entitled The Problem of Christian Democracy will be made available online in audio form sometime in the coming months.

Deep in Shanxi, the most Catholic village in China

Anthony E. Clark | Ignatius Insight

Church after church dot the landscape and high steeples rise above small villages as they do in southern France. Passing through a narrow side road one arrives and is welcomed by three great statues at the village entrance: St. Peter holding his keys is flanked by Saints Simon and Paul. Thirty minutes before Mass the village loudspeakers, once airing the revolutionary voice of Mao and Party slogans, now broadcasts the rosary. Welcome to Liuhecun, the most Catholic village in China. read more

Look for me in the Cotswolds.

Dino Marcantonio

The apologists for modernist architecture have tried for a century to gain public acceptance of and appreciation for their horrors. While the elites have almost overwhelmingly been converted, the general populace around the world still sees that the Emperor has no clothes, and almost always prefers architecture that reflects the tried and true, the local and the natural. Alain de Botton, the Swiss essayist, ‘pop philosopher’, and former ‘writer-in-residence’ at Heathrow Airport, is the latest to give it a go, this time in the pages of the modernist Architectural Record. Dino Marcantonio provides a most useful fisking. read more

Canada is a French country

Andrew Coyne | Maclean’s

At the recent Canada Day celebrations on Parliament Hill, Canadian PM Stephen Harper spoke of “the steadfast determination and continental ambition of our French pioneers, who were the first to call themselves ‘Canadians.’” At other times he has spoken of Canada as having been “born in French,” of French as “Canada’s first language,” and, most famously, of Quebec City as “Canada’s first city,” its founding in 1608 as marking “the founding of the Canadian state.” While the sentiment may seen anodyne, moreover, the implications are radical. read more

A School Chapel on Long Island

St. Anthony’s High School, South Huntington, L.I.

“I have a general disgust for Catholic architecture since the 1950s,” says Brother Gary Cregan, the Franciscan friar who is principal of St. Anthony’s High School in South Huntington. The friar was quoted by the once-great New York Times in a 2008 article on the new chapel built by the Catholic school on Long Island, recently featured on the NLM blog. The Franciscans, according to the Times, “believe that the new chapel, with its soaring 30-foot ceilings, will teach teenagers that they are ‘worshiping God, not each other.'” Many of the chapel’s furnishings were bargain finds on eBay including the confessionals, the pews, a 110-year-old stained-glass window, and a century-old statue of St. Anthony. A new bell for the chapel’s tower would’ve cost $20,000, but Brother Gary (or “Mr. Cregan” as the newspaper referred to him) found an old one for $4,000. (more…)

The Hottentots Holland Capped with Snow

Some World Cup watchers found it slightly incongruous that as they balked in the heat of the northern summer, spectators in the stadiums were bundled up for the cold. It does snow in South Africa, though not every year and usually much less the closer you are to the sea (or rather sea-level). This recent photo distributed by Die Burger shows the Hottentots Holland range, near my former neck of the woods, capped with snow.

Even on days when you can see the mountain peaks topped in white, the temperature closer to the ground still allows you to spend a care-free afternoon relaxing at a vineyard with friends.

À bas l’Académie anglaise!

Proponents of an Academy of English are guilty of leaps of logic

IT STANDS AS one of the great monuments of autonomy and decentralisation that ever existed — the English language. But this great monument is under threat from an unlikely source: one sworn to defend it. The Queen’s English Society has announced plans to form an “Academy of English” along the lines of the Académie française for French or the Real Academia Española for Spanish.

“People misunderstand things if language is not used correctly,” argues Rhea Williams of the Queen’s English Society. “Misuse of apostrophes is the best-known problem, but people also don’t seem to know about tenses any more, for example, you hear ‘we was’ a lot.”

“An academy is needed because the correct information is not something that people can find easily. I suspect that many people in this country have easier access to a computer than to a reference book. They will be able to search without embarrassment, although people should be unafraid to say that they do not know what a word means.”

“At the moment, anything goes,” says Martin Estinel, the founder of the new academy. “Let’s set down a clear standard of what is good, correct, proper English. Let’s have a body to sit in judgment.”

No less an authority than Gerald Warner of Craiggenmaddie has waded into the debate, asserting on his Telegraph blog that “all champions of literacy will wish the society success.”

The complaints raised have a great deal of justification behind them, but the establishment of an academy does absolutely nothing to solve them. Indeed, the very complaint that the misuse of English is rampant and on the rise correctly presupposes that we are already able to discern proper English from improper English.

Rhea Williams and her confrers assume that when a person says “we was”, he is also claiming that it is right and proper English for him to say so. But, on the contrary, if you heard someone on the bus say “we was” and then inquired “Is that proper English?” he would almost certainly, if perhaps sheepishly, admit that it is not.

Similarly we hear complaints about “text speak”, as the shorthand version of English used in text messages (also known as SMSs) is called. But text speak similarly makes no claims to being acceptable as proper English. None would dream of preparing a job application, for example, in text speak.

Furthermore, the Queen’s English Society does not even use proper English on its website.

The Society aims to start using its BLOG [sic] again, following a period of inactivity. If you have something to say about the English language, in the context of education, employment, the media and feel able to contribute to the debate, we invite selected guest bloggers to send in their blogs.

“Blog” is a contraction of “web log” which has rapidly achieved legitimacy, and refers to the entirety of a blog, but the QES almost certainly used the word “blog” instead of what they actually meant, “blog entries”.

The very word “blog” itself is a perfect example of the threat to English that establishing an academy poses. I dislike the word myself, but its usefulness is inescapable. We needn’t refer to that wide and varying array of websites which are in fact an agglomeration of personal writings and links to other items of note — we can simply say “blogs”. An English Academy, on the other hand, might have banished “blog” from its fatuous version of what constitutes proper English early on, in which case the language would be all the poorer, or at least all the more cumbersome.

English speakers know good use from poor use, and when they’re not sure they overwhelmingly defer to those who do know. An Academy of English would do more harm than good and would solve none of the problems that would provoke its foundation. A massive and broad-based information campaign, on the other hand, paired with the return of authoritative teaching in schools, would aid the better use of English infinitely more than a body of pedants to settle disputes that do not exist. Pressure must be exercised against broadcasters, who spread improper English through a misguided attempt at authenticity, and we must also challenge the widespread perception of a social bias against proper speaking.

All these things can be done without any academy, and indeed establishing one would take energy away from these efforts. I’m sure therefore that, pace Mr. Warner, all champions of literacy will join me in shouting “À bas l’Académie anglaise!”

Hup Holland Hup

Laat de leeuw niet in z’n hempie staan

Hup Holland Hup

Trek het beestje geen pantoffels aan

Hup Holland Hup

Laat je uit het veld niet slaan

Want een leeuw op voetbalschoenen,

kan de hele wereld aan

Want een leeuw op voetbalschoenen,

kan de hele wereld aan.

Don’t let the lion stand in his undershirt

Go Holland Go

Don’t make the beast wear his slippers

Go Holland Go

Don’t get played off the field

Because a lion wearing football shoes

Can take on the whole word.

Because a lion wearing football shoes

Can take on the whole word.

Modern Scottish Architecture

Sydney Mitchell’s Royal Bank of Scotland, Kyle of Lochalsh

Among the surprisingly large pool of under-appreciated Scottish architects is Arthur George Sydney Mitchell. His Edinbornian works include Well Court in Dean Village, Ramsay Gardens in the Old Town, and his restoration of the Mercat Cross on the Royal Mile. Sydney Mitchell also did a number of branch commissions for the Commercial Bank of Scotland (which in 1959 merged with the National Bank to form the National Commercial Bank, which in turn merged into the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1979). (more…)

Happy Dominion Day

fête du Dominion

à nos voisins du nord.

Dominion Day

to our neighbours to the north.

Libeskind Strikes Again, in Dresden

The controversial starchitect exacts Poland’s revenge on a German city

THE WAR WAS NOT kind to Dresden: the bombers of the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Army Air Force rained destruction on the Saxon capital, reducing much of the city to piles of rubble, and killing thousands upon thousands of innocent women and children in the process. One of the few buildings to survive the cataclysmic and morally reprehensible bombing campaign was the old garrison, which after the war was turned into a military museum.

Poland, whose unprovoked invasion by the Nazis sparked the Second World War, is exacting a curious revenge on neighbouring Germany, however. Daniel Libeskind, the controversial Polish starchitect, is building a monstrous addition to the Dresden Military History Museum that may not be a crime against humanity, but is undoubtedly a crime against architecture. (more…)

Three for the Army

Something you don’t see every day: a set of triplets from Pretoria recently completed basic training as part of their enlistment in the South African Army. Dirk van Zyl, Tjaart van Zyl, and Hendrik van Zyl (above, left-to-right) are 20 years old and got their mechanical engineering qualifications before enlisting in the Defence Force.

The three brothers are all part of Foxtrot Company, 3 South African Infantry Battalion based at Kimberley in the Northern Cape; Hendrik in Platoon 1, Tjaart in Platoon 2, and Dirk in Platoon 3.

Large-scale operational deployments of the South African military have been few and far between since the country withdrew from the Angolan conflict and granted Namibia independence. Since then they have mostly consisted of United Nations and African Union peacekeeping operations, as well as other endeavours such as South Africa’s 1998 military intervention in a dynastic dispute in the neighbouring Catholic monarchy of Lesotho. Current defence regulations prevent siblings like the van Zyl brothers from being operationally deployed simultaneously.

Alexander Stoddart: “An Elite for All”

Scotland’s national newspaper interviews Scotland’s national sculptor

By SUSAN MANSFIELD

The Scotsman | 22 November 2008

ALEXANDER STODDART welcomes me into his studio, and into the 19th century. “It hasn’t gone away, you see,” he says, brightly. “The 19th century is not a period in time, it’s a state of mind.”

Indeed, if one could visit the workshop of one of the great monumentalists of a century ago, it might look a lot like this: plaster casts in various stages of assembly; imperious figures missing limbs or, occasionally, a head; bags of clay which until recently were a working model of physicist James Clerk Maxwell.

Stoddart is Scotland’s premier neo-classical sculptor, the man who made the figures of Adam Smith and David Hume for Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, Robert Burns for Kilmarnock, the beautiful Robert Louis Stevenson memorial on the capital’s Corstorphine Road. He’s 49, but looks boyish, with his sandy hair and dusty lab coat cut off at the elbows. He is a man of swift, enthusiastic intelligence, rarely still, and almost never silent.

Despite once being dismissed by the Scottish Arts Council as “backward-looking, historicist and not reflecting contemporary trends”, Stoddart is busy. Around us are the plastercasts of past commissions: immense allegorical figures for the £6 million Millennium Arch in Atlanta, Georgia; religious commissions for a mysterious private client who has her own chapel “somewhere in North Britain”; parts of 70ft frieze for Buckingham Palace. A bust of Pope John Paul II for a Chicago seminary.

Soon they will be joined by James Clerk Maxwell, whose statue, commissioned by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, will be unveiled on Tuesday at the East End of Edinburgh’s George Street. Stoddart is thrilled to be sharing a street with 19th-century sculptural greats like John Steel’s Thomas Chalmers. “It’s the greatest honour to be anywhere near the company of Steel.”

And he is ready and waiting for the next question, the one about relevance. (more…)

Carbuncle Alert in Queens

Our carbuncle alarm, which went haywire over the Brooklyn Museum’s offensive new entrance, has alerted us to a new monstrosity nearing completion in the adjacent borough. (more…)

München: mees bewoonbare stad

Hoeveel kere het ek dit hoor sê? München, die Beierse hoofstad, is die mees bewoonbare stad in die wêreld volgens baie lyste deur talle mense saamgestel. Die meeste kenmerk hierdie status aan die unieke kombinasie van tradisie en moderniteit in die stad. Beiere het ’n balans getref, en die Beierse mense is baie trots op hul land — en tereg! Müncher weißwurst — bedien met mosterd en ’n krakeling — is my gunsteling wors. (Jammer, boerewors! Jou Duitse neef is tops.)

In elk geval, op die webtuis van Monocle tydskrif, Tyler Brûlé het ‘n blik op München en ondersoek waarom en ondersoek waarom het dit so ‘n goeie reputasie. Kliek hier om te kyk.

It is scandalous that in all my travels I’ve never been to any part of Germany, let alone Bavaria, considering how everyone raves about it unceasingly. Once I finally get myself to the other side of the pond permanently, it’s high up on the list of places to visit pronto (alongside the Netherlands and Finland). All in good time, all in good time…

A Palace on Princes Street

The North British & Mercantile Insurance Company, No. 64 Princes Street

PRINCES STREET IS the thoroughfare of the nation, and its sad decline during the second half of the twentieth century and only partial comeback since then are reflective of Scotland itself. The architects of Edinburgh’s New Town had no idea that Princes Street would evolve into a commercial avenue, and the street was originally laid out as a handsome row of Georgian townhouses, built between 1765 and 1800, facing Princes Street Gardens and the Old Town above behind them.

Almost immediately the mercantile and social nature of the street began to assert itself, with shops and traders setting themselves up in the converted basements and ground floors of townhouses. The New Club showed up at No. 86 Princes Street in 1837, coming from previous premises in St. Andrew’s Square and before that Shakespeare Square (where the former G.P.O. now stands).

As the Victorian era progressed, more and more of the Georgian townhouses were demolished and replaced with new buildings in the varying styles of age. It was just two years after Victoria’s death that an old company built a new headquarters in a brimming Edwardian baroque: the North British and Mercantile Insurance Company. (more…)

The World Cup Preserves Something America is Losing

The drama of sport is being systematically attacked by the bloated American Pro-Sports-Statistical-Media Complex. I can name for you three specific ways that this is happening, but there are doubtless more. First, a universal obsession with statistics. A common criticism of American culture is that it is so technological and empirical that you can’t say anything without backing it with numbers. But I have come to the darker conclusion that most sports broadcasters talk about numbers only because they have nothing else to say. I really don’t care, I really think it is meaningless, that the Chiefs have not succeeded in making a two-point conversion during the third quarter of a post-season game in the last five years. The quintessence of this obsession was illustrated this week by Bob Ley of ESPN, in the halftime analysis during the Argentina-Nigeria World Cup match. “The last time Argentina gave up a halftime lead was in the 1930 World Cup,” he said. “It just doesn’t happen.” This baffled the Spaniard Roberto Martinez, an ESPN commentator and former professional soccer player, who responded: “That was a different team, Bob.” Sports teach us that the possible is greater than the probable; statistics applied to sports is probability’s revenge on possibility.

The second destructive force is the delusion of the Instant Replay. We appeal to the camera when we become afraid of the human element in sport. We think that the precision and justice that the replay can provide for us will defuse the pain that is intrinsic to any competitive sport. In games we see that the best-trained can’t always play their best, and that those with the best eyes don’t always make the right call; the imprecision and the deficiency are also elements in the drama. The Instant Replay is an attempt to quell the drama, as if sports would be better without it. All it actually does is stir confusion about what a game really is, and every time we interrupt a game to watch a video, we strike a blow at the soul that keeps the game moving.

Interruptions, also, are what television commercials are. That basketball and [American] football are structured in such a way as to accommodate for television commercials is a scandal. Who enjoys watching “The Godfather Part II” when it is sliced and diced by ads for sitcoms and acne medication? The interruptions wake us up from the dream of the drama; basketball and football lose something in this constant interruption.

All of this may sound bleak, but the answer to it is flickering in a billion television screens worldwide this month. As we watch the World Cup this summer, we should be conscious that we are witnessing a sport that is resisting. It resists, if nothing else, the tyranny of television commercials. No commercials interrupt the 45 minute flow of a half of soccer—there are no “TV time outs.” The narrative builds and is resolved within continuous time, and it demands that we reclaim the patience and the attention spans most of my generation lost sometime in the late 1990s.

Moreover, even though every now and then somebody within FIFA complains that Instant Replay should be introduced into the game, most fans accept that the game includes injustices. We suffer through them, and we play again the next day. Geoff Hurst scored a “goal” for England in the 1966 Final which actually did not cross the line. Maradona scored a “goal” with his hand against England in the quarterfinals of 1986 (he attributed it to God; five minutes later, he scored the greatest goal in World Cup history). France would not be in the World Cup this year, and Ireland would be, had Thierry Henry not handled the ball during a qualifying match. What can you do? Better to make a sacrifice than to kill the sport.

As for statistics—American soccer broadcasters, too, are beholden to them. But one could always learn Spanish and switch to Univision.

The World Cup this year has its own set of stories which will congeal into the dramatic. The Brazilian squad has betrayed its principles of jogo bonito (beautiful play) and has adopted a pragmatic approach which yields victories without flair. Ironically, the German side looks more playful and creative in attack than Brazil does. Lionel Messi of Argentina will be trying to live up to his reputation of being the greatest Argentine player since Maradona. And there is a tough Paraguayan side you will not want to miss.

Most importantly, there is a drama that you will not want to miss—one that retains certain human elements which are besieged in our hyperactive media age.

The Houses of Parliament, Dublin

The Physical Incarnation of Ireland’s Golden Age

THE OLD HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT in Dublin are probably at the top of my list of favourite buildings in the world. Now the headquarters of the Bank of Ireland, it has a long and varied history, and its exterior composition is one of surprising unity for a structure the components of which were designed by three architects. It is supposedly the first purpose-built parliament building in the world, and stands on the site of Chichester House, a stately home adapted for use by the Irish Parliament from the 1600s onwards.

The location, with a history dating back centuries, is just south of the Liffey river upon what was then known as Hoggen Green. A nunnery existed on the site which was supressed during Henry VII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. A large private house was then built on the site, set back from the street, eventually known as Chichester House. (It likely incorporated some of the old convent’s structure). Among the esteemed inhabitants of the house were Sir George Carew, sometime Lord President of Munster, Sir Arthur Chichester, after whom the house was named, and the Anglican Bishop Edward Parry is known to have had a lease on the place during his lifetime.

The building must have been seen as holding some public significance, not only because it was located adjacent to the University of Dublin (of which Trinity College is the sole constituent institution), but it was home to the Irish Law Courts for a time beginning with the Michaelmas legal term of 1605. Towards the end of the seventeenth century, no later than October 1692, the Irish parliament began to meet at Chichester House on College Green. (more…)

Holland in die Kaap

’n Groep van Nederlanders in die Kaap het hulle Volkswagen Beetle in die Hollandse patriotiese kleure geverf om hul steun in die Sokkerwêreldbeker te vertoon en hul het hierdie vrolike YouTube video gemaak ook. (Hulle blog, in Nederlands, is 34 graden Zuid).

Watter span steun ek? Ach, baie! Teen Engeland, het ek die Verenigde State gesteun (maar ek haat die “Anyone-But-England” houding van baie in die Britse Eilande buite Engeland). Teen Duitsland, het ek die Aussies gesteun. En natuurlik al die Maties moet BAFANA BAFANA steun!

So vir groepe A-H (onderskeidelik) ons is vir Suid-Afrika, Argentinië, die VSA (of Engeland), Australië, Nederland, Nieu-Seeland, niemand in groep G, en Chili.

An “Unknown Delegate”?!?!?

It’s Bilderberg  season again, which normally has all the conspiracy theorists this side of Roswell up in a flurry. This year, however, the organisers have cheated by having a website and even a press release concerning the proceedings. The Guardian has a photo gallery of the various guests arriving, mostly attired in the tiresome suit-but-no-tie combination which has become all too prevalent of late.

season again, which normally has all the conspiracy theorists this side of Roswell up in a flurry. This year, however, the organisers have cheated by having a website and even a press release concerning the proceedings. The Guardian has a photo gallery of the various guests arriving, mostly attired in the tiresome suit-but-no-tie combination which has become all too prevalent of late.

The super-trendy left-wing newspaper, however, demonstrates its typically Euro-centric mindset through its caption for this photo: “Francisco Pinto Balsemão, a former prime minister of Portugal and the CEO of Impresa, says goodbye to an unknown delegate.” An “unknown delegate”?!?!? That’s no less than Dambisa Moyo, the most famous Zambian in the world (referred to as “our girl” in Zambian newspapers), not to mention author of a New York Times bestseller and African star-of-the-hour for over a year now. Honestly, Mr. Guardian!

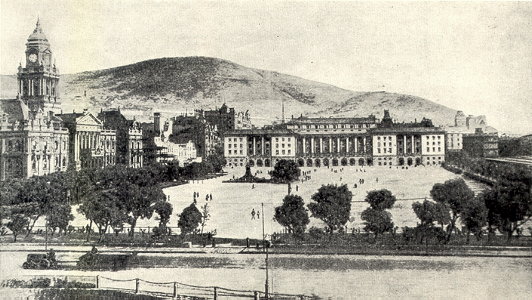

Unbuilt Cape Town: Municipal Offices

UNBUILT ARCHITECTURAL PROPOSALS fascinate me. Unfortunately most of the books documenting the more prominent examples of unbuilt buildings focus on space-age hyper-modernist ideas that never got off the drawing board, but these tend towards the tawdry and ridiculous. Far more interesting are the rejected proposals for buildings that did get built — for example the rival schemes to rebuild the Palace of Westminster after the 1834 fire — or this example of a proposal for a building never executed. I came upon these scheme thanks to the uploads of the Flickr user Berylmd. While Cape Town has a splendidly grand City Hall in an Edwardian Baroque style, the city fathers were unwise in providing insufficient space for the ever-blossoming municipal bureaucracy. This plan would have put a new municipal office building spanning the entire western side of the Grand Parade, replacing those little unremarkable market buildings whose existence on the square persists to this day. (more…)

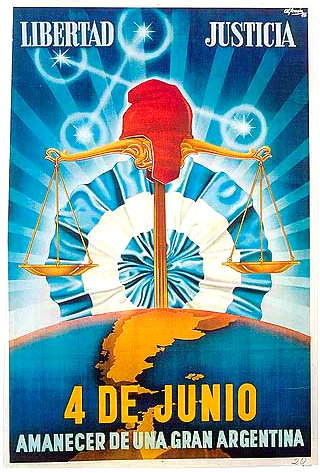

4 de Junio

On June 4, 1943,  a murky group of Argentine military officers called the GOU (standing for United Officers’ Group, or Government, Order, Unity) overthrew President Ramon Castillo and ended the Década Infame, or ‘Infamous Decade’ that had begun with the 1930 coup against Hipólito Yrigoyen. The ’43 coup was led by General Arturo Rawson, who served as President of Argentina for a month before being replaced by the more politically minded Gen. Pedro Ramírez.

a murky group of Argentine military officers called the GOU (standing for United Officers’ Group, or Government, Order, Unity) overthrew President Ramon Castillo and ended the Década Infame, or ‘Infamous Decade’ that had begun with the 1930 coup against Hipólito Yrigoyen. The ’43 coup was led by General Arturo Rawson, who served as President of Argentina for a month before being replaced by the more politically minded Gen. Pedro Ramírez.

Ramírez sympathised with the Axis powers in the Second World War, and his inability to successfully maintain Argentina’s neutrality in the face of U.S. pressure led to his resignation and succession by Gen. Edelmiro Farrell, who was viewed by most as the instrument of his charismatic junior, the infamous Col. Juan Perón (with whom we are all too familiar).

This poster produced by the junta incorporates a number of the symbols of Argentine patriotism and nationalism. ‘Liberty’ and ‘Justice’ are proclaimed the principles of the junta, and underneath the date of the coup is announced the ‘Dawn of a Greater Argentina’. The Phrygian cap of liberty, a frequent Argentine emblem, rests atop the scales of justice while the stars of the Southern Cross imply a divine favour over the new regime.

The map of Argentina coloured in yellow includes the British colony of the Falkland Islands and Antártida Argentina, the Argentine Republic’s claimed possession on the Antarctic continent (which overlaps with competing claims by Chile and the United Kingdom). Behind the whole composition, the Argentine Cockade looms ascendant like a rising sun, affirming the text’s proclamation of a new dawn under the nationalist-revolutionary regime.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories