World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

‘Decisions, decisions…’

Rather horrifyingly, one of the proposals would have erected a monumental screen closing off the forecourt, completely spoiling the view of Edward Lovett Pearce’s beautiful façade.

Luckily the Bank chose Francis Johnston to harmonise the competition designs into the building we know today.

Voltaire’s Works Are Not Dead

They Are Alive: And They Are Killing Us

“It was a little after nine in the evening; the sun was setting, the weather superb. … Nothing is rare, nothing is more enchanting than a beautiful summer evening in St Petersburg. Whether the length of the winter and the rarity of these nights, which gives them a particular charm, renders them more desirable, or whether they really are so, as I believe, they are softer and calmer than evenings in more pleasant climates.”

The Soirées Saint-Petersbourg of Joseph de Maistre are philosophical dialogues that sometimes border on the mystical and delve into the dark recesses of human nature. They are eloquent, fascinating, and beautiful, traversing a broad range of subjects while hovering around evil and why it exists in the world.

In this extract from the Fourth Dialogue, the Count — generally taken to represent the author’s own view — objects to the young Chevalier citing Voltaire approvingly.

A critic might call it a rant; if so, it is at least a beautiful one:

Party in the Overberg

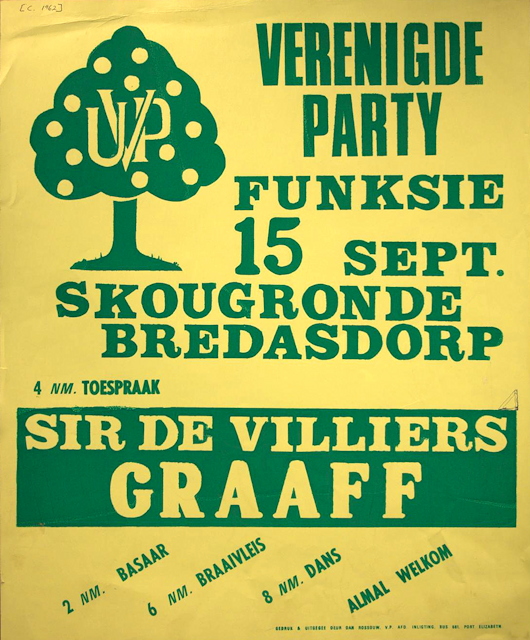

Alongside a bazaar, a braai, and dancing, a speech by Sir De Villiers Graaff is the selling point of this poster advertising a United Party (Verenigde Party) get-together in the beautiful Overberg region of the Cape.

“Sir Div” was the inheritor of one of only twelve South African baronetcies and led his party from 1956 until 1977 when it merged with the Democratic Party of verligte ex-Nationalists to form a new entity.

The broadly centrist party had lost power to the republican Nats (creators of apartheid) in 1948, and suffered splits that led to the creation of the Liberal Party and the United Federal Party in 1953, the National Conservative Party in 1954, and the Progressive Party in 1959.

The party’s emblem was a happy little citrus tree.

The Wyndham Monument, Silton

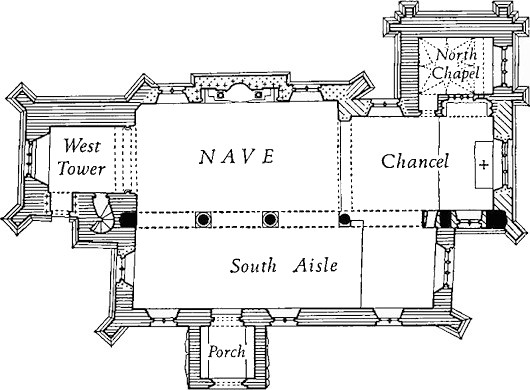

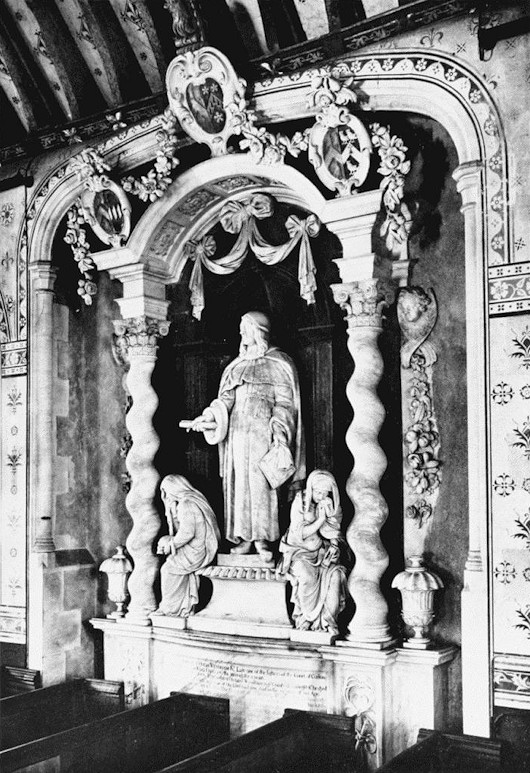

The charmingly haphazard Church of St Nicholas in Silton is home to what is arguably the finest funerary monument in Dorset not in a major church.

Sir Hugh Wyndham (1602–1684) lived through the difficult time of the Civil War and was first advanced in the law under Cromwell’s military dictatorship. It was the worst of both worlds for Wyndham, as the republican authorities never trusted him while after the Restoration his comfort with Cromwell meant he was deprived of office. Still, Charles II was no small-minded man, and after a royal pardon was granted Wyndham was appointed a Baron of the Exchequer and knighted.

The monument he left behind at Silton is is believed to be the earliest work of the Flemish sculptor Jan van Nost (also known as John Nost the elder). Sir Hugh is depicted in his judge’s robes, flanked by two mourning figures believed to represent his first and second wives. (The third wife is at least represented by having her arms impaled with Wyndham’s in one of the three heraldic sheilds gracing the monument’s surrounds.)

Nost’s sculpture was unveiled in the chancel of the parish church in 1692 but the Victorians thought it rather dominated the small sancutary. In 1869 a small recess was constructed in the north wall of the nave and the Wyndham monument was carefully moved there. The sculptor was also responsible for the monument to John Digby, 3rd Earl of Bristol, in Sherborne Abbey not far away, and one can see the parallels. The Earl, as it happened, married Rachel Wyndham, the younger daughter of Sir Hugh Wyndham.

Zeist’s Zest for Traditional Architecture

The Daniel Marotplein, a residential square in the town of Zeist, provides a fine recent example of traditional architecture in the Netherlands. Designed by the TU-Delft-trained architect Diederik Six, the twenty houses surround a green square named after the Huguenot craftsman and artist Daniel Marot some of whose handiwork is in the nearby Slot Zeist.

The slot (schloss/castle/house) is associated with the Protestant Moravian brotherhood who were invited to live nearby by Cornelis Schellinger in the mid-eighteenth century, and the Daniel Marotplein takes inspiration from the two squares of houses they lived in flanking the castle. (more…)

A Fifty Pound Note

The recent arrival of the new fiver has caused some flurry of excitement and one of the notes finally reached the Cusackian exchequer via the barmaid at the Ox Row Inn in Salisbury on Friday night. I’m indifferent to the design; it’s inoffensive but I’d prefer to see Churchill depicted in his coronation robes rather than Yousuf Karsh’s iconic photograph.

My favourite Bank of England note, however, remains the Series D £50 first issued in 1981 designed by the Black Country artist Harry Eccleston. Sir Christopher Wren lookings crackingly baroque, and St Paul’s Cathedral looms like a great ship over the City of London he helped to rebuild after the Great Fire 350 years ago.

Eccleston was the first banknote designer to work fulltime for the Bank of England which he joined in 1958, retiring in 1983, and introduced the concept of historical figures from British history gracing the back of the notes (which are of course fronted with an image of the Sovereign). This particular note was the first fifty-pound note to be issued since 1943. It was replaced in 1994 and withdrawn from circulation two years later.

Oliver VII

by Antal Szerb, trans. by Len Rix

Pushkin Press (2013), £12, 208 pages

Hungarian by nationality, Catholic by faith, Jewish by blood — Antal Szerb was capable of touching the boundaries of intense seriousness bordering on the mystical (as in Journey by Moonlight) or magical (The Pendragon Legend) even though he is probably better known as paragon and only member of the interwar neo-frivolist school of literature.

Here he is at his frivolous best with a novel about the monarch of a Ruritanian kingdom in crisis who abdicates and escapes to Venice incognito, where he falls in with a crowd of confidence tricksters who ultimately, unaware of the ex-king’s true identity, force him to impersonate himself.

In Oliver VII, romance, intrigue, and the perpetual allure of the genteel portion of the criminal class all combine in an enjoyable farce.

The Red Mass in Edinburgh

The opening of Scotland’s judicial year was marked this past Sunday by the Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh offering the customary Red Mass in St Mary’s Cathedral.

This year Archbishop Leo Cushley was joined by Lord Drummond Young and his fellow Senators of the College of Justice, Lord Uist, Lord Doherty, Lord Matthews, and Lady Carmichael.

Gordon Jackson QC, the Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, and Austin Lafferty of the Law Society of Scotland joined many sheriffs, QCs, advocates, solicitors, trainee solictors, paralegals, and law students.

“These men and women serve the nation in a high office and come here to ask the Lord’s blessing upon this year’s work that they carry out on our behalf,” Archbishop Cushley noted in his homily.

“Know that we appreciate the difficult and complex tasks that you have and the duties that you perform – which are very onerous – on behalf of us all and that you be assured of our prayers and our support for all that you do to apply the law of the land with virtue and with justice and with mercy.”

The Old Cannon Brewery

Robert Gwelo Goodman is one of my favourite South African artists whom you might recall when I introduced you to one of his paintings of the Groote Kerk in Cape Town. It’s not surprising that he lived in a unique dwelling — an old brewery in the verdant Cape Town suburb of Newlands, nestled as it is in the nape of Table Mountain.

Now Gwelo’s old brewery is up for grabs. (more…)

Die Ou Swaai Pomp

The old water pump at the corner of Prince Street and Sir George Grey Street in the Cape Town neighbourhood of Oranjezicht was part of the system created by the Swede Jan Frederik Hurling in the 1790s for his farm, Zorgfliet. This particular structure was erected at the pump site in 1812 to a design by Louis Michel Thibault, embellished with a water-sprite gargoyle attributed (inevitably) to Anton Anreith.

It was operated by swinging the wooden handle on the side to and fro, hence why it is known as a swaai, or “swinging”, pump.

The photo above is the work of the Cape photographer Arthur Elliott whose work not only documents the early architecture of the Cape but more often than not manages to do so in an artistic and evocative manner.

Elliott is especially valuable considering how many of these structures faced the wrecking ball in the intervening century since he took his photographs, though — as you can see from a Google StreetView capture below — the Old Swaai Pump is still in its place today and is a monument protected by national and provincial law.

A Baroque Church Portal

This church portal in the Oude Kerk of Amsterdam was originally in the Nieuwezijds Kapel, or Church of the Heilige Stede. That church was originally built in commemoration of the 1345 Miracle of Amsterdam, but after the ‘Alteration’ of 26 May 1578 — when Amsterdam’s Catholic city government was deposed and replaced by a Calvinist one — it and all the city’s other churches were taken over by the new Protestant administration.

In 1908 the elders of the Protestant congregation of the Nieuwezijds Kapel decided to demolish the fifteenth-century church and build a smaller one on the site, while building shops on the remainder of the site to prevent the resurgent Dutch Catholic church from building any chapel or shrine on it. This seventeenth-century baroque enclosed portal was then transferred to the Oude Kerk where it remains today.

Despite the anti-Catholicism of the Nieuwezijds Kapel elders in 1908, the Miracle of Amsterdam is still comemmorated every year on 15 March when thousands of pious Hollanders march in the evening Silent Procession (Stille Omgang). This year’s procession attracted 7,000 participants.

An Old Name Returns to Banking

or: What Daniel O’Connell has to do with the 2008 Banking Crisis

Daniel O’Connell was a remarkable man by any stretch of the imagination, and is most often recalled for his part in bringing about the Relief Act of 1829 which emancipated the Catholics of Great Britain and Ireland from an officially oppressed legal status. Among his many achievements, however, was in London in 1825 founding the National Bank of Ireland.

As the RBS Group’s website notes, O’Connell:

…helped draw up the agreement that established it, spoke at public meetings to drum up support for it, invested in it, attended its first board meetings and, in 1836, was appointed its governor. He became an important figurehead for the new bank and there was even a proposal, not implemented, to put a bust of O’Connell on the bank’s notes.

The National Bank was created with the aim of injecting cash into the rural economy in Ireland, and its charter ensured that half of its returns would accrue to local shareholders in the country. O’Connell, not the best manager of financial affairs, ended up accruing huge personal debts to the bank and had to be quietly bailed out by several others (commencing a tradition of surruptitious banking amongst the nation’s major politicians).

Anyhow, the National Bank expanded across Britain and Ireland. In 1966 its Irish core was sold to the Bank of Ireland, and the English and Welsh branches were acquired by the National Commercial Bank of Scotland (which was a 1959 merger of the National Bank of Scotland and the Commercial Bank of Scotland). This, in turn, merged into the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1969, with the superfluous National Bank branches being turned into Williams & Glyn’s Bank the following year. (more…)

A Land, not a Republic

Bohemians seek to rename Czech Republic as ‘Czechia’

What are we to make of the growing movement against the name ‘Czech Republic’? It seems a welcome development, although one has a certain hesitancy in adopting the name ‘Czechia’ which somehow just doesn’t ring true from the English tongue.

Many will still automatically recall ‘Czechoslovakia’, an artificial country invented in 1918 which lasted a surprising seventy-four years. Its two successor states will celebrate their twenty-fifth anniversary of independence next year, and perhaps this landmark event has provoked some introspection regarding the country’s name.

Many will still automatically recall ‘Czechoslovakia’, an artificial country invented in 1918 which lasted a surprising seventy-four years. Its two successor states will celebrate their twenty-fifth anniversary of independence next year, and perhaps this landmark event has provoked some introspection regarding the country’s name.

It’s not that the Czech Republic is alone: there are plenty of countries whose official names included an adjectival demonym — the French Republic, the Italian Republic, and the Hellenic Republic spring to mind. But these three examples all have names that more readily spring to mind — France, Italy, Greece — and which are used more frequently then the official state names.

Besides the Czech Republic, the only other example of a country known only as ‘the [demonymic adjective] Republic’ is the Dominican Republic, which cannot be known as Dominica owing the nearby sovereign island of the same name. (The island Dominica was named after Sunday whereas the DR was named after Saint Dominic, the patron of its largest city.) Even the Central African Republic is often referred to as Centrafrique (in French, at least).

Is it a move against republicanism? Not especially. When neighbouring Hungary adopted its new constitution it dropped the state name ‘Hungarian Republic / Republic of Hungary’ in favour of just plain ‘Hungary’ while maintaining a republican form of government. More influential perhaps is that it’s often viewed as a bit tinpot-dictatorship to have the word ‘republic’ in your country’s everyday name. (more…)

St Pancras Town Hall

St Pancras Town Hall is an interwar classical building by the architect A.J. Thomas (of whom I know little). The façade is a little clunky but in the warmer months it’s adorned with arrangements of flowers that soften this stern civic edifice with a bit of welcome frivolity.

When the Metropolitan Borough of St Pancras was merged with the neighbouring bailiwicks of Hampstead and Holborn to form the London Borough of Camden in 1965 this was chosen as the town hall of the new entity, so it’s now referred to as Camden Town Hall.

But of course of all the buildings under the patronage of the fourteen-year-old, fourth-century martyr Pancras, the most prominent is the international railway station across the Euston Road (below) that connects this metropolis with the rest of the continent across the Channel.

Canalside Wanderings

The sun put its hat on this weekend, and after a delicious and vaguely German breakfast by King’s Cross on Saturday I fancied a little canalside wandering. Walking the Regent’s Canal from the new Central Saint Martins all the way to Paddington, I stumbled across the Catholic Apostolic Church in Little Venice (above). It has been over ten years since I popped in to the former Edinburgh outpost of this strange and fascinating denomination, now much reduced in numbers since its apex in the late Victorian period. (more…)

Suid-Afrika

Suid-Afrika — ’n kleine bietjie van Hemel.

Germania

I’ve been reading Golo Mann’s History of Germany Since 1789 — cracking stuff.

This depiction of Germania, the personification of the German nation, was for a stained-glass window in the Reichstag building, built between 1884 and 1894 in Berlin and since 1999 home once again to the German parliament.

Haus Altmark

While the remarkable rebuilding and rehabilitation of Dresden is of a much more recent vintage, the historicist design of Haus Altmark (Herbert Schneider, 1953-1956) in that city is another good example of the Socialist Classicism of the DDR.

(c.f. Leipzig Opera House)

Smuts at Leiden

For quite some time, Leuven — in what is currently known as Belgium — was the only university in the Netherlands. It is still (barely, some argue) a Catholic university, and after the Protestant revolt sealed its rule over the northern part of the Dutch realms, William the Silent founded a university at Leiden as a Calvinist academy in 1575.

Leiden University has had strong links with South Africa from the earliest days. Ds. Johannes de Vooght — in the 1660s, the second leraar of Cape Town’s Dutch Reformed congregation — studied here, as did numerous predikante of that period and onwards, including Ds. Petrus van der Spuy, the first NGK minister to be born in South Africa.

South African politicians studied here aplenty: Sir Christoffel Brand (first Speaker of the Cape Parliament); Jan Brand (fourth president of the Orange Free State); Marthinus Steyn (sixth and final president of the O.F.S.); and Nicolaas Diederichs (third staatspresident of the Republic of South Africa).

Probably the first South African to be granted an honorary degree by Leiden (c. 1830) was Antoine Changuion, the founder of the Dutch language movement which advocated preserving Dutch as the cultural language of the Afrikaners against the emerging Afrikaans.

It was in 1948 that Leiden granted the greatest Afrikaner — Field Marshal Smuts — a Doctorate of Law honoris causa. Smuts was on his way back from Cambridge where he had been granted the honour of being installed as Chancellor of the University. Even Die Burger, a Nationalist paper opposed to his Verenigde party, found the event worthy of a caustic near-compliment:

“We may differ from him on many issues, but the honour which he has won for the Afrikaner does not leave us untouched.”

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Christ Church December 29, 2024

- A Christmas Gift from the Governor December 24, 2024

- Oude Kerk, Amsterdam December 24, 2024

- Gellner’s Prague December 19, 2024

- Monsieur Bayrou December 18, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories