World

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

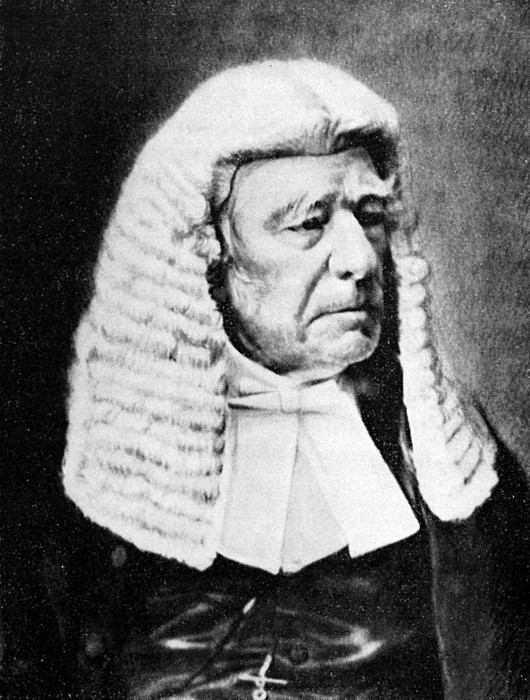

Sir Christoffel Brand

Look at that cragly visage! It belongs to Sir Christoffel Brand, the first Speaker of the House of Assembly in the Cape Parliament.

Brand was born in Cape Town in 1797 and left for the Netherlands in 1815, where he studied at Leiden. In 1820 he was awarded a doctorate in law based on his dissertation Dissertatio politico-juridica de jure coloniarum on the legal relationship between colonies and the metropole, and returned to the Cape. (more…)

Christmas on College Green

There are some good (if brief) shots of the Irish House of Lords chamber in this Christmas ad for the Bank of Ireland, 0:35-0:45.

The former Irish Houses of Parliament on College Green in Dublin were the first purpose-built parliament building in the world, and were purchased by the Bank of Ireland after the parliament was abolished by the Act of Union in 1800.

Unfortunately a condition of sale was demolishing the elegant octagonal Commons chamber at the centre of the building, to prevent it being used in the effort to have the Act of Union repealed.

Sir Thomas Cusack (1505-1571) has the distinction of having at times served as the presiding officer of both the upper and lower houses of the Irish Parliament. From 1541-1543 he was as Speaker of the House of Commons, in which role some scholars argue he was a prime mover behind the legislation erecting Ireland as a kingdom.

In the following decade he served as Lord Chancellor of Ireland, presiding in the House of Lords, from 1551 until 1555 when revelations about his involvement in the creative finances of Sir Anthony St Leger’s viceregal regime brought about Sir Thomas’s dismissal and (temporary) imprisonment.

He returned to favour when the Earl of Sussex was appointed viceroy, but never again held high office.

Of course, all that was before this neoclassical building was erected, when Parliament met mostly in Dublin Castle.

Church of the Intercession

The huge and spacious interior of the Church of the Intercession, New York. One of Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue’s masterpieces; so much so that he decided to be interred in the north transept of the church.

Hamburger Abendblatt

The German advertising agency Oliver Voss created this series of ads for the Hamburger Abendblatt, Hamburg’s daily evening newspaper.

Oliver Voss have done web and print ads for the Abendblatt before but the illustrations in this series of posters strike a jovial pose, feeling perfectly contemporary while still informed by a sense of the 1950s.

The summery beach scene is my favourite.

Marinus Willett

In one of the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum’s American wing, behind the Tuckahoe-marble façade of the old Assay Office (moved here from Wall Street), hangs this portrait of Col. Marinus Willett of the Continental Army’s 5th New York Regiment.

Born in 1740, the second of thirteen children, Willett attended King’s College before being commissioned a lieutenant in a New York provincial regiment during the Seven Years’ War (or French and Indian War as it’s known more locally). (more…)

Mendicant Architecture in Mediaeval Oxford

An interesting video from two American academics on the subject of Mendicant architecture in mediaeval Oxford, with some three-dimensional theoretical reconstructions of the Dominican and Franciscan houses in the city.

Both orders returned to Oxford in the twentieth century. The Capuchins refounded Greyfriars in 1910 and it was recognised as a permanent private hall (PPH) of the University in 1957. Its end as an academic institution was announced sadly on its fiftieth anniversary in 2007, but Greyfriars continues as a Capuchin friary.

Blackfriars under the Dominicans is still going strong, exercising a triple function as a priory of the Order of Preachers, a house of studies for the English province of the Order, and a PPH of the University of Oxford.

Judging Dress

After some absence, The Sybarite has returned and, in A Love Supreme, he weighs in on the very important matter of judicial dress.

I am, it will surprise no-one to know, deeply traditionalist in such matters. I can see the argument for discarding formal court attire in cases involving children, who might be intimidated by wigs and gowns (as a child, I myself would have been as happy as a pig in the proverbial). But I feel strongly that “work clothes”, whether worn by judges, barristers, politicians or clerks in Parliament, are important. They are part of the persona. You are not Alf Bloggs, you are Mr Justice Bloggs and you are performing an important public role. When you put on the clothes, you put on the role. Of course, I am fighting a rearguard action here – I know that the tide of public opinion is against me. If the clerks at the Table in the House of Commons still wear wigs in ten years’ time, I will be (pleasantly) surprised.

As the Supreme Court was set up in the modish New Labour years, it was inevitable they would dispense with much of the ceremonial. The Justices wear lounge suits to hear cases, though I think in some cases the barristers still wear wigs and gowns. The one concession has been the black-and-gold gowns which the Justices don for special occasions. These are fine so far as they go – and, as observed above, Lady Hale of Richmond likes to accessorise hers with a Tudor bonnet – though they bear on the back the badge of the Supreme Court, which I think looks a bit tacky and smacks of footballers’ names and numbers on the back of their shirts. But they also look a bit odd worn over lounge suits or equivalent. At least successive Lord Chancellors since the role was recast by Blair have retained formal court dress for high and holy days. Mind you, the current occupant, Miss Truss, does look a bit like the principal boy in a pantomime when she wears knee breeches. But fair play to her for continuing to wear the traditional robes, even if the full-bottomed wig seems now to have gone the way of the dodo.

It could be worse. The Supreme Court Justices could wear ghastly zip-up gowns like their American counterparts – you just know they’re made of nylon – over their suits, though I have some time for Justice Ginsberg for adding a lace jabot to tidy up her garb a little. But ceremonial is something that Britain does so well. The Supreme Court could have looked so much better with Justices in gowns and traditional judicial clothing. A wig here and there wouldn’t go amiss.

I couldn’t agree more. Especially on the matter of the badge of the Supreme Court on the back on the gowns, which is simply naff. (See image below.)

But why do the justices of the Supreme Court have (what I think of as) chancellorial gowns anyhow? What is the origin of this style of black-and-gold gown? Did it start with the Lord Chancellor and spread to the Speaker or vice versa? Or have some species of judge always worn chancellorial gowns? The chancellors of universities have likewise adopted it, though its precise form varies from institution to institution, as one might expect in matters of academic dress.

Incidentally, I was speaking with Bob Geldof the other day about Senator W. B. Yeats, about whom Mr Geldof has done a documentary. As we were discussing Yeats’ contribution to the Irish Senate, Mr Geldof mentioned that Yeats had been in discussions with Hugh Kennedy, the Chief Justice of the Irish Free State, about introducing new designs for Irish judicial dress. The results, according to just about everyone, left much to be desired and so the British tradition carried on for the most part. As is so often the case, doing nothing is the least bad option.

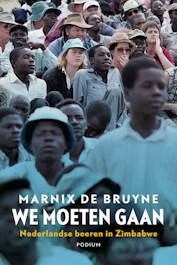

The Dutch in Rhodesia

…and why they stayed there.

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Why did so many people emigrate from the Netherlands in the fifties? Why did hundreds of them choose to settle in what was then called Rhodesia, today’s Zimbabwe? And why did so many of them stay after 1965, when the country was led by a white-minority regime, faced an international boycott and was engulfed in a bloody guerrilla war?

De Bruyne attempted to answer these questions through a recent seminar at Leiden University’s African Studies Centre. The university has rather handily made a recording of the seminar available online.

Daar’s ook ’n interview (in Nederlands) met Mnr de Bruyne in Mare, die koerant van die Universiteit Leiden.

(Dave: hierdie post is vir jy!)

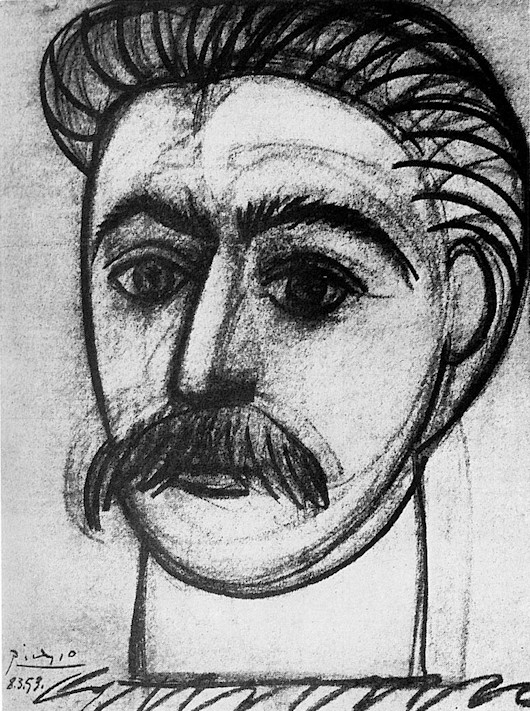

The Death of God the Father

When Stalin’s death was announced on Friday, 7 March 1953, Aragon called in Pierre Daix and rattled off a shopping list of features to honour Stalin in a special issue of Les Lettres françaises. […] Since Picasso had always refused to do a portrait of Stalin from a photograph, Daix sent a telegram to him at Vallauris saying, ‘Do whatever you want,’ and signed it ‘Aragon’.

Picasso’s drawing of Stalin, which depicted him as a curiously open-eyed young man, arrived at the very moment Les Lettres françaises went to press. Daix took the picture to Aragon. He admired it and said that the party would appreciate the gesture. While it was being set into the front page, office boys and typists crowded round the picture. Everyone thought it ‘worthy of Stalin’.

Daix was overjoyed to be the one who had commissioned Picasso’s first portrait of the Soviet leader and rushed it down to the printers. But a few hours later, when the edition had been run off, the mood in the building had completely changed to one of fear. Journalists from L’Humanité, passing by, spotted the drawing and cried out that it was unthinkable that any Communist publication should consider such a representation of ‘le Grand Staline’.

Pierre Daix promptly rang Aragon at his apartment; Elsa Triolet answered. She told him angrily that he was mad to have even thought of asking Picasso for such a drawing.

‘But really, Elsa,’ Daix broke in, ‘Stalin isn’t God the Father!’

‘Yes, he is, Pierre. Nobody’s going to reflect much about what this drawing of Picasso signifies. He hasn’t even deformed Stalin’s face. He’s even respected it. But he has dared to touch it. He has actually dared, Pierre, don’t you understand?’ […]

Antony Beevor & Artemis Cooper (1994, London)

Fête Chiracienne

AS TODAY IS the eighty-fourth birthday of Monsieur Jacques René Chirac, I thought it’d be best to share a few images of the underappreciated fifth president of the Fifth Republic (not to mention sometime Mayor of Paris, Prime Minister of France, and Co-Prince of Andorra) doing the things he does best. (more…)

Wall Street

Well, actually it’s Broad Street looking down past the New York Stock Exchange to Federal Hall, which itself is on Wall Street.

Most of Broad Street was originally a canal (hence its width) but in 1676 it was filled in and laid out as a street.

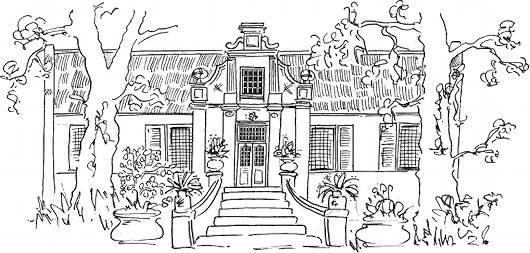

Muratie

The Stellenbosch estate of the artist Georg Paul Canitz

We had supper with Mr. Canitz, the painter, one Sunday night, by the light of candles in a fine Dutch candelabra, and drove back to Stellenbosch in moon light which had transformed the countryside into the most entrancing fairyland imaginable.

Great clumps of trees in unexpected places gave an eeriness to the white ribbon of road which stretched across the valley. The soft evening breeze of magic scents lulled us, and we drowsed to the hum of the car bearing us homeward.

That memory is still vivid to me so I shall turn from our Golden Road, and “…muse awhile, entoil’d in woofed phantasies.”

So the architect Rex Martienssen described a visit to Muratie, the home of the artist Georg Paul Canitz, in 1928. Canitz was a Saxon, born in Leipzig, where his parents had hoped he would pursue a military career. Both his zeal and talent as an artist appeared early on, and so he ended up at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. After further studies in Italy, Paris, and the Netherlands, a chest ailment drove him to the interior of Südwestafrika in 1907.

Canitz healed quickly in the dry air but could not find a cure for the striking beauty of the new world around him. His wife and children were summoned from Germany, and three years later he moved to Stellenbosch after falling in love with the “City of Oaks”.

Canitz devoted himself to his passions: riding, painting, and teaching (both at his own art school and at the University). Riding to a party at Knorhoek one day he stumbled upon the little house and farm at Muratie and was quickly enamored of the place. It wasn’t long before he had purchased it and moved his family there.

G P Canitz

At Muratie, the painter developed a further art: that of winemaking. In this he was assisted by the legendary Dr Perold — first chair of viticulture at Stellenbosch. Canitz became a pioneer of the pinot noir grapes which have since become a South African staple. Perhaps even more he developed the skills of a kind and generous host, for which he was well reputed throughout South Africa. He would welcome friends and guests — among them Martienssen and his architectural students as cited above — throughout the year. In warmer months they came for the swimming pool and the breezy stoep, while in winter a fire awaited, or perhaps a few rounds of strong drink in the Kneipzimmer.

I like to think this was Canitz’s favourite room at Muratie: bedecked with benches, the light streaming in through a stained-glass windows, and the walls covered in naturalistic painting as well as graffitied signatures and sayings in German, Afrikaans, French, and Greek.

The painter died in 1958, leaving Muratie to his daughter, who in 1987 sold it to members of the Melck family who had owned it from 1763 to 1897. (The house was first built in 1685.) I suspect Canitz would have greatly appreciated his handiwork being passed back to those who had looked after the place for many generations before him. The Melcks, unsurprisingly, have a great reverance for the history of the estate. They even go so far as to leave the cobwebs which have accrued go undisturbed and ask visitors to do likewise.

And, even today, the wine still flows!

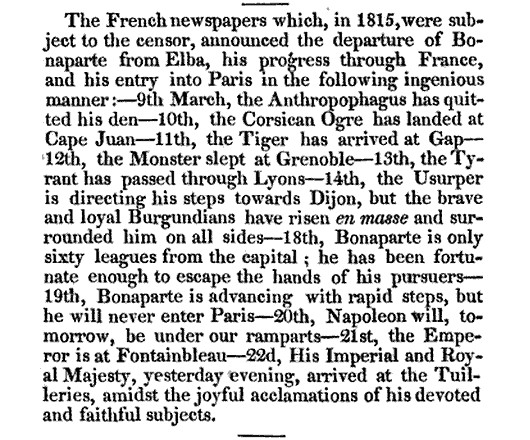

The Anthropophagus Has Quitted His Den

The Museum of Foreign Literature Science and Arts was a Philadelphia periodical edited by the prodiguously talented and unjustly neglected Eliakim Littell.

In January 1831 his review published this little snippet of headlines claimed to have been clipped from French newspapers:

The French newspapers which, in 1815, were subject to the censor, announced the departure of Bonaparte from Elba, his progress through France, and his entry into Paris in the following ingenious manner:

March 9 THE ANTHROPOPHAGUS HAS QUITTED HIS DEN

March 10

THE CORSICAN OGRE HAS LANDED AT CAPE JUAN

March 11

THE TIGER HAS ARRIVED AT GAP

March 12

THE MONSTER SLEPT AT GRENOBLE

March 13

THE TYRANT HAS PASSED THOUGH LYONS

March 14

THE USURPER IS DIRECTING HIS STEPS TOWARDS DIJON

but the brave and loyal Burgundians have risen en masse

and surrounded him on all sidesMarch 18

BONAPARTE IS ONLY SIXTY LEAGUES FROM THE CAPITAL

He has been fortunate enough to escape the hands of his pursuersMarch 19

BONAPARTE IS ADVANCING WITH RAPID STEPS

But he will never enter ParisMarch 20

NAPOLEON WILL, TOMORROW, BE UNDER OUR RAMPARTS

March 21

THE EMPEROR IS AT FONTAINEBLEAU

March 22

HIS IMPERIAL & ROYAL MAJESTY, yesterday evening, arrived at the Tuileries, amidst the joyful acclamation of his devoted and faithful subjects.

In the Old Dutch East Indies

Little Holland’s rule over this vast land – today the world’s largest Muslim country by population – never loomed large in the European imagination (the Netherlands excepted) and thus has been too easily forgotten. Peter van Dongen’s Rampokan series of graphic novels (in Herge’s ligne-claire style) is the most prominent recent attempt to shine some light on the Dutch East Indies and it has obtained a bit of a cult following.

The colonial architecture went through the usual transformations, from awkward hybrids of the motherland and the vernacular to a cool and crisp classical elegance of the later imperial buildings. Henri Maclaine Pont’s work at Bandung is probably the most successful Dutch take on local building traditions, and in some ways Geoffrey Bawa is his spiritual offspring.

The ministries of Indonesia’s government still convene in elegant Dutch colonial buildings, though the names have all changed. The Daendels Palace is now the Finance Ministry, Buitenzorg is now Bogor, and the old Koningsplein is now the Medan Merdeka or Freedom Square. (more…)

Church of St James, Spanish Place

Always interesting to see a building you know well from a perspective you’ve never seen before, as in this photo of the Church of St James, Spanish Place, taken from Manchester Mews. The church somehow seems more imposing — like a great rounded keep.

A few months ago I was corralled into some favour or other that required a bit of muscle to move this there and whatnot, the payoff of which was it afforded an opportunity to explore the triforium of this Marylebone church and see the interior of the building from an entirely new vantage point.

It also meant being able to view in better detail the beautiful stained glass windows — many of them the gift of various Spanish royals, given that this parish originates as the chapel of the Spanish embassy (hence its name).

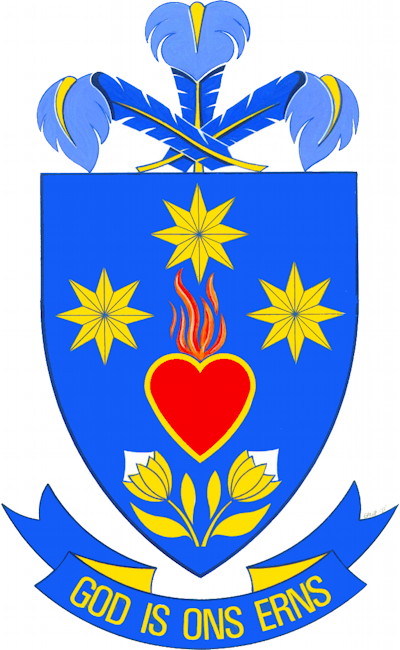

Arms of the Oudtshoorn Oratory

An explanation of the arms of the Afrikaans-speaking Oratory of St Philip Neri in Oudtshoorn, South Africa (edited from their own information).

Russia’s Demographic Turnaround

Most  large developed countries have been facing demographic crises, with Russia one of the worst in the past few decades. The Financial Times this week reports, however, that Russia is facing a demographic turnaround: “Rising birth rate, tumbling death rate, and immigration drives population rebound” as the subheadline puts it.

large developed countries have been facing demographic crises, with Russia one of the worst in the past few decades. The Financial Times this week reports, however, that Russia is facing a demographic turnaround: “Rising birth rate, tumbling death rate, and immigration drives population rebound” as the subheadline puts it.

In 2000, deaths at 2.23 million outnumbered the 1.27 million births by nearly a million. In 2013, 1.94 million births finally outnumbered 1.91 million deaths, while the first quarter of 2016 has witnessed a 5 per cent drop in mortality compared to just a year before.

Still, the low birth rates of the 1980s and 1990s will continue to have a reverberating effect on the working-age population, as the children who weren’t born then will obviously not have children and grandchildren. Pension ages are being changed accordingly, rising to 65 for men and 63 for women as compared to 60 and 55 respectively up until now — a Communist hangover ridiculously low in comparison to Western countries.

Despite a perilous economic condition thanks to collapsing commodity prices, Russians clearly feel their country is in a much more stable condition than the topsy-turvy 1990s. There can be no greater vote of confidence in the future than to have children.

Previously: The World Turned Upside Down

Speyer

This 1961 postage stamp celebrates the consecration, nine centuries earlier, of the Imperial Cathedral Basilica of the Blessed Virgin of the Assumption and Saint Stephen at Speyer — today the largest Romanesque church still standing.

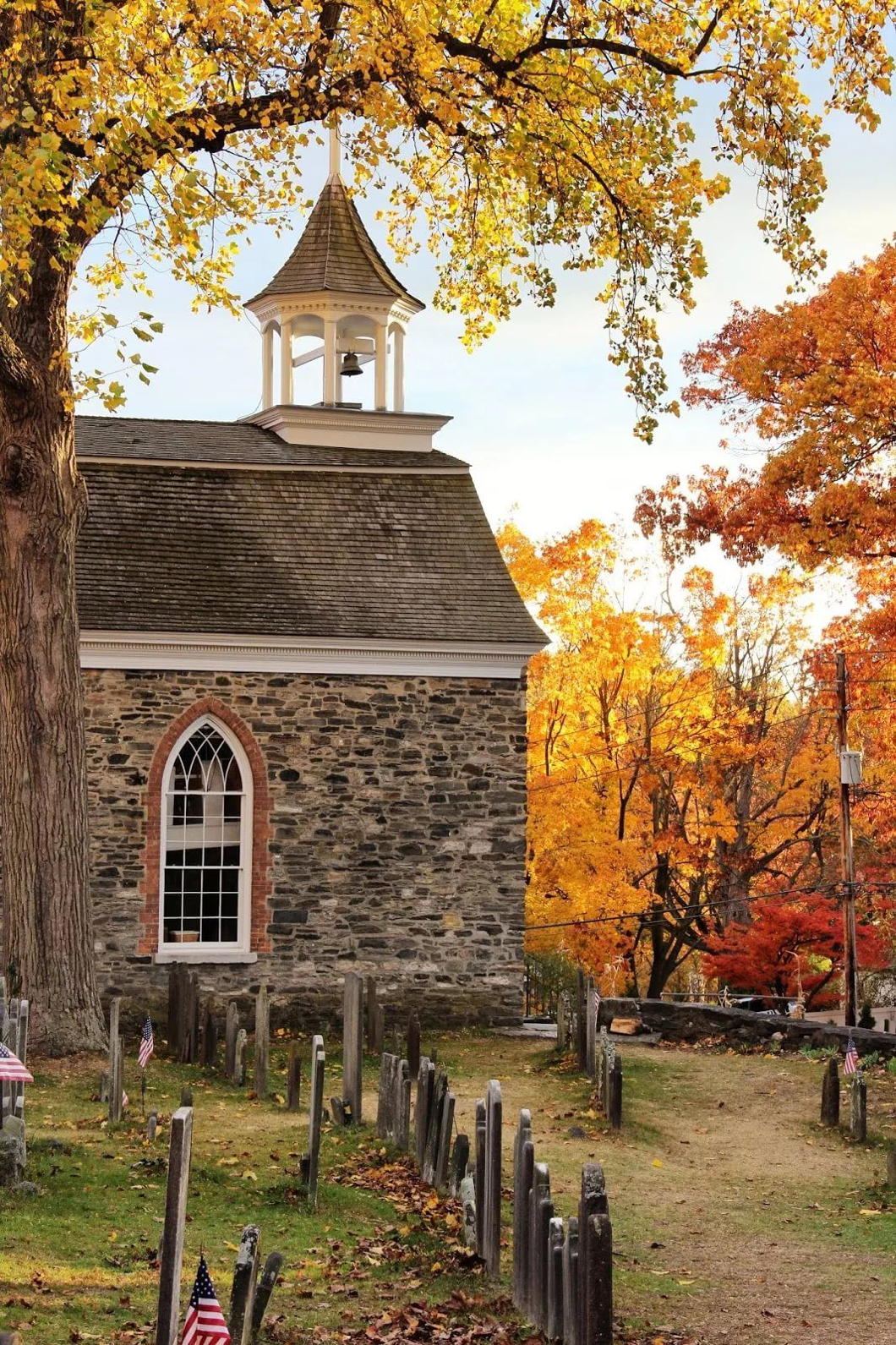

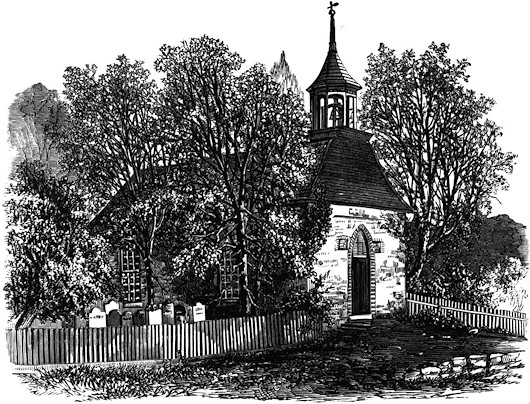

The Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow

If there is any season which is plus New-Yorkaise que les autres then it must be autumn, and around the time of Hallowe’en in particular.

Thanks to the fertile imagination of Washington Irving, buried in the cemetery of the Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow, the Hudson Valley is the spiritual home of this ancient Celtic feast now implanted in the New World.

The other day I dusted off the huge single-volume complete works of Irving – almost the size of an old Statenvertaling – and re-read his most famous tale, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”.

Irving describes the position of the Old Dutch Church:

The sequestered situation of this church seems always to have made it a favorite haunt of troubled spirits. It stands on a knoll surrounded by locust trees and lofty elms, from among which its decent whitewashed walls shine modestly forth, like Christian purity beaming through the shades of retirement. A gentle slope descends from it to a silver sheet of water bordered by high trees, between which peeps may be caught at the blue hills of the Hudson. To look upon its grass-grown yard, where the sunbeams seem to sleep so quietly, one would think that there at least the dead might rest in peace.

On one side of the church extends a wide woody dell, along, which raves a large brook among broken rocks and trunks of fallen trees. Over a deep black part of the stream, not far from the church, was formerly thrown a wooden bridge; the road that led to it and the bridge itself were thickly shaded by overhanging trees, which cast a gloom about it even in the daytime, but occasioned a fearful darkness at night. Such was one of the favorite haunts of the Headless Horseman, and the place where he was most frequently encountered.

The tale of the Headless Horseman is now, partly thanks to various popular reinterpretations of it, well known even outside the Hudson Valley. I remember as a wee lad growing up in that part of the world our Scout uniforms had a badge bearing the image of the “Galloping Hessian”.

Johannes Kip’s View of London

View and Perspective of the City of London, Westminster, and St James’s Park

This view of London and Westminster is most notable for the unique perspective it takes: a bird’s eye view from above the Duke of Buckingham’s house, later acquired by the Crown and now, as Buckingham Palace, the primary royal residence.

This printing of Kip’s view, which comes up for auction soon at Daniel Crouch Rare Books, may have been printed after 1726 as it incorporates Gibb’s steeple of St Martin-in-the-Fields.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Christ Church December 29, 2024

- A Christmas Gift from the Governor December 24, 2024

- Oude Kerk, Amsterdam December 24, 2024

- Gellner’s Prague December 19, 2024

- Monsieur Bayrou December 18, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories