New York

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

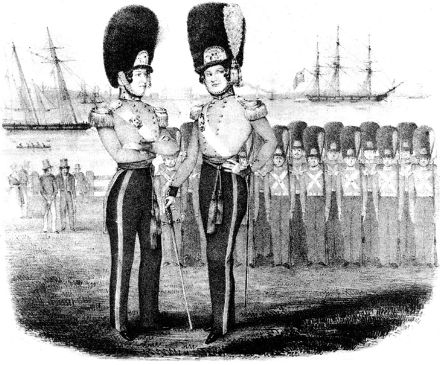

The Light Guard

Officers of the New-York Light Guard, an antecedent of the Old Guard of the City of New York. The City Guard and the Light Guard combined in 1826 to form the Old Guard.

Categories: The Old Guard | Militaria

Upcoming Events

Tradition in New York

November 1, 2007 (Thursday)

The Feast of All Saints

Holy Day of Obligation

Latin Mass (Extraordinary Form)

7:30 pm

Church of Our Lady of Good Counsel

230 East 90th Street

(between 2nd & 3rd)

November 2, 2007 (Friday)

The Commemoration of All Souls

& First Friday

Latin Mass (Extraordinary Form)

6:30 pm

Church of St. Vincent de Paul

123 West 23rd Street

(between Avenue of the Americas & 7th Avenue)

November 5, 2007 (Monday)

Annual Solemn Requiem

of the New York Purgatorial Society

Latin Mass (Extraordinary Form)

6:15pm

Church of St. Agnes

143 East 43rd Street

(between 3rd & Lexington)

November 17, 2007 (Saturday)

The Sleep of Reason

Part one of the Roman Forum’s Modern Image & Catholic Truth series

9:00am – 4:00pm

Church of Our Lady of Good Counsel

230 East 90th Street

(between 2nd & 3rd)

Modern man has a positive image of himself that has been shaped and very effectively propagandized since the time of the Renaissance. In three conferences between November and May, the Roman Forum’s Modern Image and Catholic Truth series will explore the gap between this image and the true predicament in which the individual and contemporary society now find themselves trapped.

Part One: The Sleep of Reason

Modernity speaks of the eighteenth century Enlightenment as the “Age of Reason”. But proponents of the Enlightenment were often dubious about the ability of the human mind to understand man and nature and more interested in limiting the scope of rational activity than increasing it. Much of their labor ended by declaring the universe to be the mere plaything of the human will and passion, while practical backing for many of the Enlightenment’s goals came from strange combinations of mystical speculation and calls for the exercise of Machtpolitik.

9:00am

Holy Mass

(Latin, Extraordinary Form)

9:45am – 10:30am

Registration

10:30am – 11:30am

Pietism, Jansenism, Enlightenment

& the Victory of Power over Reason

Dr. John Rao

11:45am – 12:45pm

Adam Smith and Karl Marx:

A Study in the Logic of the Enlightenment

Dr. Jeffrey Bond

12:45pm – 2:15pm

Lunch

(A second Mass is also available in the Church)

2:15pm- 3:15pm

The Scientific Revolution & the Social Contract

Theory of Hobbes, Locke & Rousseau

Rev. Dr. Richard Munkelt

3:15pm – 4:00pm

Panel Discussion

For further information please contact the Roman Forum (dvhinstitute@aol.com or call 212-645-2971).

COST

$30: Reserve by November 10th

$40: Pay at the door, entrance and lunch

$10: Pay at the door, entrance alone

Checks payable to:

The Roman Forum

11 Carmine Street, 2C

New York, NY, 10014

The Rapalje Children

Oil on canvas, 50¾″ x 40″

1768, New-York Historical Society

Durand’s painting of the four children of this prominent mercantile family of Manhattan is one of the finest examples of group portraiture from the colonial period in America. From left to right are Garret (b. 1757), George (b. 1759), Anne (b. 1762), and Jacques (b. 1752).

The painter had come to New York from Virginia two years previous to paint individual portraits of the children of the Beekman family. Art historians suspect he was born or trained in France. Durand later returned to Virginia, where he continued to paint until his death in 1805.

Corpus Christi Church

Corpus Christi Church, West 121st Street, New York: perhaps my favorite Catholic church interior in all New York, and one which simply cries out for a traditional Mass. (more…)

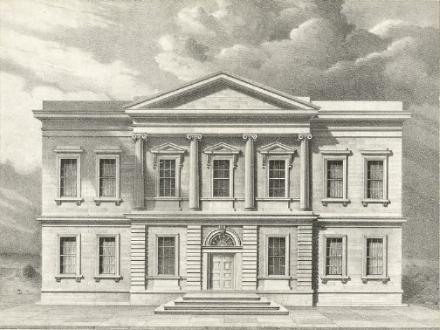

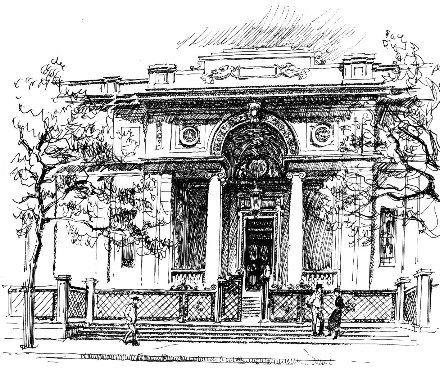

The Assay Office

THE ASSAY OFFICE was built in 1822 as the New York branch of the Bank of the United States, located at 15½ Wall Street. The (Second) Bank of the United States was the second attempt at a central bank for this country. Eventually, the central bank grew too powerful, trying to manipulate politics and master the economy itself, and so it was abolished in 1836. The building later became the Assay Office, an adjunct to the Customs House and Sub-Treasury next door, which itself is now known as Federal Hall National Monument. When the Assay Office was torn down, the façade was preserved and donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Robert W. de Forest in 1924. It is now presented in the glass-covered courtyard of the American Wing of the greatest museum of art in the New World. (more…)

Along the Hudson

THE TOLLBOOTH AT THE Bear Mountain Bridge is built in a whimsical style meant to harken back to the Dutch patriarchs of old who roamed and ruled (and fell asleep in) these lands. The Bear Mountain Bridge spans the Hudson River between Bear Mountain and Anthony’s Nose, and was the longest suspension bridge in the world upon its completion in 1924. (As of 2007, it is the 62nd longest suspension bridge). The South Gate of the Hudson Highlands is composed of Anthony’s Nose rising from the east bank and Dunderberg (lit. thunder mountain) on the west, while Wind Gate between Breakneck Ridge and Storm King Mountain marks the northern reach of the Highlands. (more…)

USMA 37, Temple 21

A HIKE UP into the Hudson Highlands, to see West Point trounce Temple University 37-21. (The last time I saw Temple play at Michie Stadium was in September 1994, when they beat Army 23-20). Army opened this game well by scoring a touchdown and field goal in the first minute, but gave the Temple Owls too much leeway, matching Army 21-21 by the half. Luckily, the Black Knights pulled through in the second half and finished the Owls off rather nicely. (more…)

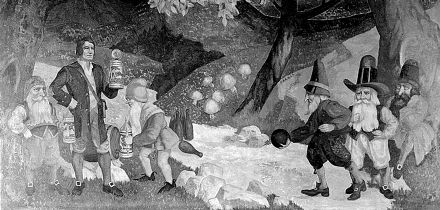

Rip van Winkle

POOR RIP van Winkle; I always felt bad for him. He falls asleep for twenty years, and returns to his own native village where is now unknown and taken for some strange vagrant. “I am a poor quiet man, a native of the place, and a loyal subject of the king, God bless him!” he exclaims, in blissful ignorance of the Revolution which took place during his slumber. “A tory! a tory! a spy! a refugee! hustle him! away with him!” cry the by-standers.

I have long thought that Washington Irving was trying to make a subtle traditionalist point here: the definition of a good citizen has been arbitrarily changed. If a man was a good New Yorker in 1765 and hasn’t changed, why is he a traitor in 1785? It’s clearly ridiculous, except to proto-Jacobins and ideologues.

Anyhow, the lesson of the story: drink not from the flagons of odd-looking personages playing nine-pins amidst the Hudson Highlands.

Previously: Rip van Winkle

They don’t all hate us

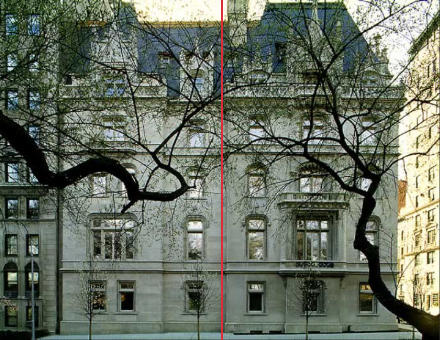

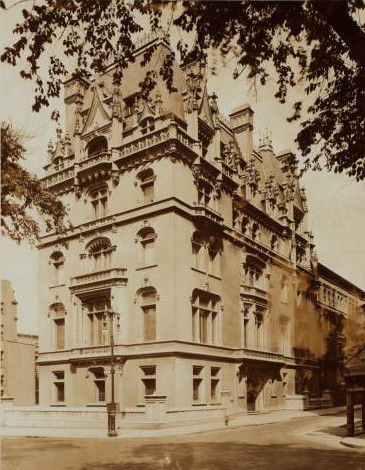

THE JEWISH MUSEUM sits at the corner of 91st Street and Fifth Avenue in the old Warburg mansion. It was expanded in 1993, nearly doubling its frontage on the avenue. See the modern addition? No? That’s the point.

In the photograph above, the section to the right of the red line is the original Warburg house, built in 1909 and designed by C.P.H. Gilbert. The section to the left of the red line is the 1993 addition. If only the directors of the Morgan Library and the Brooklyn Museum had been similarly inspired.

The Architects: They Really Hate Us

ONE OF THE GREAT things about the Morgan Library on 36th and Madison was that it used to reflect (and indeed protect) the glories of European civilization. Since its recent renovation, however, it merely expresses the post-civilization status of the mother continent. One cannot help but feel bad for poor Mr. Morgan, who would surely frown upon the vulgarity which has been thrust upon his life’s achievement: one of the finest collections of manuscripts, rare books, and drawings in the entire world. (more…)

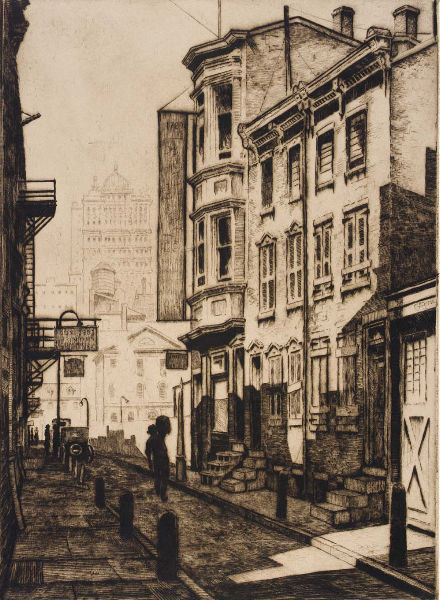

Ludlow Street

George A. Bradshaw, Ludlow Street

Drypoint on paper, 8 7/8 ” x 6 3/8 ”

1935, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Ludlow Street is the home of the world-famous Katz’s Delicatessen.

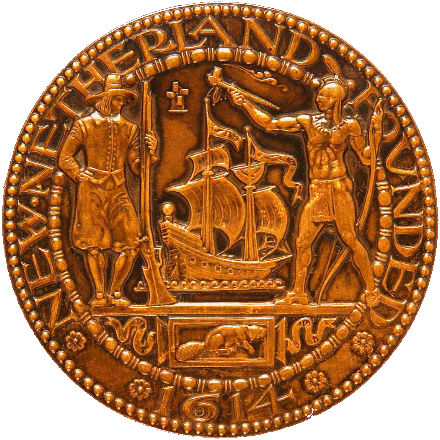

New Netherland Medal

Paul Manship, New York Tercentenary Medal

Bronze, 2 3/4 inch diameter

1914, Smithsonian American Art Museum

A Walk in the Country

In need of a little fresh air this morning, I went for a walk amidst the lush greenery of our fair county, and took a few snapshots to show you my explorations. Shall we? (more…)

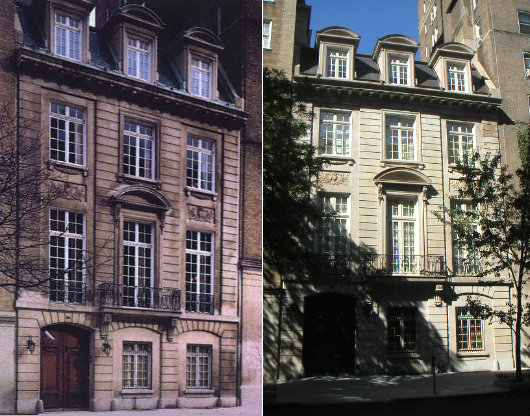

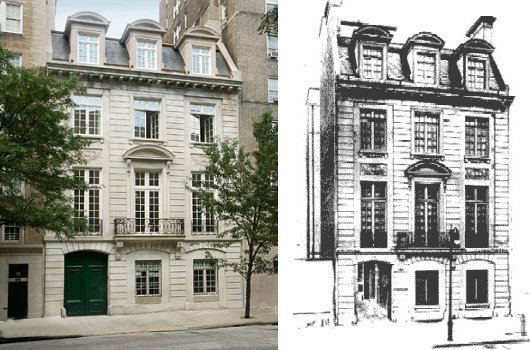

The Dahlgren Residence

No. 15 East Ninety-Sixth Street, New York

THE UPPER EAST SIDE is crossed by a number of wider cross-streets, of which 96th Street has long been agreed as the northern boundary of the neighborhood. (Overeager real estate agents have recently taken to advertising properties above that boundary as being located in the “Upper Upper East Side”). At number 15 on East 96th Street sits a splendid townhouse of superb design and execution often known as the Dahlgren residence. (Seen above, before and after complete restoration).

Lucy Wharton Drexel was of the Philadelphia Drexels, from which also came Saint Katharine Drexel, the founder of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, as well as the initiators of Drexel University in that Pennsylvanian city. Young Miss Drexel married Mr. Eric B. Dahlgren, son of Admiral John A. Dahlgren, inventor of the Dahlgren Gun used during the Civil War at a ceremony in the Philadelphia cathedral officiated by Archbishop Corrigan of that see, and the couple soon moved to Manhattan where Mr. Dahlgren had a seat on the New York Stock Exchange. The Dahlgrens themselves were a prominent Catholic family, with Eric and his brothers attending Georgetown University, where to this day the main chapel bears the Dahlgren name. (Well-to-do Catholics must have been in short supply at the time, because after Lucy and Eric’s marriage, Lucy’s sister Elizabeth was married to Eric’s brother John).

Diary

EARLY YESTERDAY EVENING I found myself on the West Side and with a bit of free time, so I sauntered down Broadway to Columbus Circle to finally investigate in the flesh this great public place after its complete rehabilitation some two years ago. I am happy to report that the Circle’s refurbishment is quite a successful one. My only reservations were minor details, but as these were all done in an extremely simple and smooth modern style, they are much less objectional, and perhaps serve to focus attention on the sculptor Gaetano Russo’s splendid monumental column from which Cristóbal Colón, Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Viceroy and Governor of the New World presides over the grand plaza consecrated to his memory.

Colón’s name is rendered on the monument as ‘Cristoforo Colombo’, which seems appropriate since the monument was paid for by public subscription raised by Italian-Americans, and it is commonly assumed that Columbus was Italian. He may have been Genoese, Catalan, Portuguese, or Corsican, but he described himself as being from lands under the rule of Genoa, which lends significant credence to the Genoese and Corsican theories. In Spain, however, he is apparently Spanish, or so one daughter of Iberia, the wife of a frequent reader of this little corner of the web, informs us. The happy couple were strolling through Columbus Circle recently and the good lady was shocked to discover the purported Italian origin of the man who brought Christianity to the New World. After all, Spain’s national day — the Día de la Hispanidad — is October 12, the day in 1492 that Columbus first set foot in the New World. (In woebegone Venezuela, the vulgar socialist dictator has proclaimed October 12 as the Día de la Resistencia Indígena, or Day of Indigenous Resistance, and the Columbus Column in their capital city of Caracas was toppled on that day in 2004).

Anyhow, not only was the good lady was shocked at our monument’s proclamation of the Discoverer’s Italian-ness but the combination of that with the presence in Columbus Circle of the beautiful U.S.S. Maine Monument led the observer to conclude that the public plaza should be instead be named “Anti-Spain Square”. It was the disastrous sinking of the Maine, after all, which led to the Spanish-American War, the result of which was America’s most unfortunate and regretful act of taking Spain’s empire off her hands. (Contrary to Mr. Kipling’s idealistic urging of America to take up the imperial mantle in his poem ‘White Man’s Burden’, this turned out to be a fairly good deal for the Spaniards, and a very poor deal for the peoples of the United States).

Politics aside, I enjoyed the few minutes during which I ruminated in the square (or circle, if ye be pedants). I recall many years ago the debate surrounding how to improve Columbus Circle that there was a near-universal desire for there to be more trees but that the very shallow depth between the street surface and the subway below presented difficulties in this regard. The redesigners have solved this problem by encircling the center of the circle with a raised ridge, on which are planted a number of trees which, we trust, will be even more appreciated as they mature. The raised ridge, which features jets of flowing water around the inner circle, also serves to innoculate the center from the noise of the traffic which, the Circle being situated at the confluence of Broadway, Central Park West, Central Park South, and Eigth Avenue, is considerable.

And so, I judge the new Columbus Circle a success, and I am happy to the report that the American Society of Landscape Architects concur, having awarded it their General Design Award of Honor. Another random fact which surprisingly few people know is that Columbus Circle is the spot from which distances to New York are numerated, akin to Moscow’s Red Square and London’s Trafalgar Square (if I recall correctly).

LEAVING COLUMBUS CIRCLE, I sauntered back up Broadway to another of Manhattan’s engaging places, Lincoln Center. Critics accused the architects of the performing arts complex of cribbing off of Rome’s E.U.R., but one wishes the three halls facing Lincoln Center’s plaza had the same crispness of those modern Roman structures. The thirty years between the E.U.R. of 1930s Italy and the Lincoln Center of 1960s New York were years in which the quality of modernism declined just as greatly as its supremacy increased. Despite this, the plaza of Lincoln Center is one of the most successful public places in Manhattan. I have often lamented the absence from New York of the open piazza so common on the Continent. This plaza competes with Central Park’s Bethesda Terrace as the best example of the type in Manhattan.

The plaza is raised above the neighboring Lincoln Square (one of the many triangular squares created by Broadway’s healthy disregard for the grid) and is reached by a gentle rise of stairs. Viewed from the square it appropriately seems like a stage upon which all our great dramas are played. The dance of the New York City Ballet in the State Theatre on the left, the music of the New York Philharmonic in Avery Fisher Hall on the left, and in the center, the Metropolitan Opera in the Metropolitan Opera House; the greatest opera company in the Americas, not to mention one of the best in the entire world. And from the hour of seven or so on the evening of performances, the three arts mix and mingle in the plaza as attendées wait to meet their companions and enter whichever of the respective halls they are to spend the evening. Some jealously preserve a seat of honor on the rim of the central fountain, while others hide from the elements (the beating sun, the heaving rain) in the shelter of the arcades, while still more meander slowly to and fro around this piazza dell’arte.

It’s unfortunate, then, that the elders of Lincoln Center insist on erecting temporary stage structures in the middle of the plaza, partially obstructing the fountain, during the warmer months when, above all other times, it should be open for all to enjoy. The creators of Lincoln Center conceived of the obvious desire for outdoor performances during the summer, and so they built the bandshell in Damrosch Park in between the Opera House and Avery Fisher Hall, just diagonally adjacent to the plaza. Surely the plaza is meant to be an open space where all the events can mix, blend, interact, influence, before finally separating into their appropriate places. If there are to be outdoor performances, hold them where they were meant to be, and if that place suffers from some malfunction of design, then redesign that place rather than rudely interjecting a particular event into what was meant to be the public square for all.

THIS PARTICULAR EVENING it was into Avery Fisher Hall for a performance of the New York Philharmonic, now in its 165th year. The program was Rossini’s overture to Semiramide and Schubert’s Symphony No. 3 in D major (D.500), with Dvořák’s Symphony No. 5 in F major (Op. 76). Riccardo Muti wielded the conductor’s baton and the result was definitely less than was expected. I had only heard Muti’s conducting on the radio in passing and, while admittedly not devoting much thought to it, he seemed a fairly capable conductor. In person, however, he left much to be desired. Rossini’s overture was merely lackluster but Schubert’s symphony was actually surprisingly poor. Perhaps the worst thing was observing Muti in action, for the man looked like an utter fool. His conducting seemed unnatural, choreographed, even foppish. And those ridiculous jestures towards the first violins! I wanted to slap the man, and I shouldn’t be surprised if the violins wanted to themselves. Towards the middle of the Schubert symphony, I began to think of the man as a proper ass, the tails of his evening jacket acting the part of hind legs. My only solution to the St. Vitus’s dance on the conductor’s dais was to shut my eyes and imagine that I was there in the Austrian capital in that autumn of 1815, after the chancellors and ministers of the crowned heads of Europe had departed the Congress of Vienna when peace and order were plotted, in the home of Otto Hatwig where (scholars posit) the work was premiered.

The friend I accompanied that evening actually knows about the inner workings of music (I am actually an ignoramus on the subject, and simply like what sounds good to me) and agreed completely with me on the subject during the intermission. Luckily, the Dvořák fared better, but one had the niggling suspicion that this was the Philharmonic working its magic in spite of Mr. Muti, rather than at the command of his baton. My knowledge and appreciation of Dvořák has slowly grown, from that first passing fondness we all have for his Symphony No. 9 “From the New World”. My appreciation for the Philharmonic grows, when I see they have printed in the program that Mr. Dvořák was born in Mühlhausen, Bohemia, rather than the more modish style of “Nelahozeves, Czech Republic” that would find favor elsewhere.

Perhaps I am too hard on Mr. Muti. Perhaps he and the Philharmonic were simply not a good fit for eachother. At any rate, I shouldn’t complain as one doesn’t often get box seats to a sold-out performance with every seat in the hall occupied (though, to be honest, the sound is better down in the orchestra seats). But how I wish I could have seen von Karajan while he was alive!

After the baton had finally fallen for the night, my friend and I had the same stroke of genius at exactly the same moment and decided to head up to good old Café Lalo, but unfortunately everyone else had the same idea (Saturday night? Lalo’s? What did we expect?) so we comforted ourselves with a pint or two at the Parlour instead.

New York Needs a Monarchy

In the business section of today’s New York Sun, of all places, Liz Peek gives us another reason why we need a monarchy. In ‘Why America Needs Its Own Queen’s Award‘, Ms. Peek profiles the Queen’s Award for Enterprise, initiated by Royal Warrant in 1966 as the Queen’s Award for Industry and awarded to British companies for excellence in international trade, innovation, and sustainable development.

In the business section of today’s New York Sun, of all places, Liz Peek gives us another reason why we need a monarchy. In ‘Why America Needs Its Own Queen’s Award‘, Ms. Peek profiles the Queen’s Award for Enterprise, initiated by Royal Warrant in 1966 as the Queen’s Award for Industry and awarded to British companies for excellence in international trade, innovation, and sustainable development.

Of course, Ms. Peek attempts to offer some possible solutions to our detrimental lack of monarchy with regard to this particular aspect, but none of them have quite the appeal of restoring the monarchy. All that would really be necessary would be to pass an amendment removing fourteen words from Article IV, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution. This is the part that requires the member states of the United States to have republican forms of government. This removal would at least give states the option of becoming monarchies, which is only fair, after all.

Category: Monarchy

The Knickerbocker Greys

The Knickerbocker Greys, the Upper East Side corps of cadets, is celebrating its 125th year in existence. Both the Times and the Sun have featured articles on the Greys:

‘Celebrating 125 With the Knickerbocker Greys‘ by Gary Shapiro (The New York Sun)

‘Manhattan’s Littlest Soldiers‘ by Eric Königsberg (The New York Times)

Above: A mother mends a cadet’s uniform.

Below: Cadets assembled in an Armory corridor. (Note the interior scaffolding due to the State’s grievous neglect of the Armory).

A Sienese Gem Lost

STEALING A GLANCE at the photo above, the viewer would easily be forgiven for mistaking the vista for that of a subway entrance in turn-of-the-century Siena, Italy. The proud medieval tower lurks over a comely metal-and-glass structure of continental flavor. However the city fathers of that ancient Italian municipality never deigned to erect an underground railway. The precise locus of the vista is far removed: it is the corner of Park Avenue and 33rd Street, and the building behind the subway entrance is not the town hall of Siena, but rather the armory of the 71st Regiment, New York National Guard.

When the earlier Romanesque Revival armory of the Seventy-First Regiment burnt down in 1902, it was decided to build the new armory on the same, though slightly enlarged, site. The 1905 construction was built to the design of the architectural firm of Clinton and Russell, and was clearly inspired by the Palazzo Pubblico (the town hall, photo at right) of Siena, on that city’s Piazza de Campo. While the Seventh Regiment Armory contains the finest interiors of any military building in City, and probably the entire Empire State, the exterior of the Seventy-First’s armory was far superior. Even though the interior was not to the same lofty standard as the Seventh, it was by no means lacking, for it had all the wood-panelled rooms filled with military regalia from times gone by which one expects of New York’s armories from the period. (more…)

When the earlier Romanesque Revival armory of the Seventy-First Regiment burnt down in 1902, it was decided to build the new armory on the same, though slightly enlarged, site. The 1905 construction was built to the design of the architectural firm of Clinton and Russell, and was clearly inspired by the Palazzo Pubblico (the town hall, photo at right) of Siena, on that city’s Piazza de Campo. While the Seventh Regiment Armory contains the finest interiors of any military building in City, and probably the entire Empire State, the exterior of the Seventy-First’s armory was far superior. Even though the interior was not to the same lofty standard as the Seventh, it was by no means lacking, for it had all the wood-panelled rooms filled with military regalia from times gone by which one expects of New York’s armories from the period. (more…)

King Jagiello of Poland

My favorite statue in Central Park is that of King Władysław II Jagiełło of Poland, by the Turtle Pond. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories