New York

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

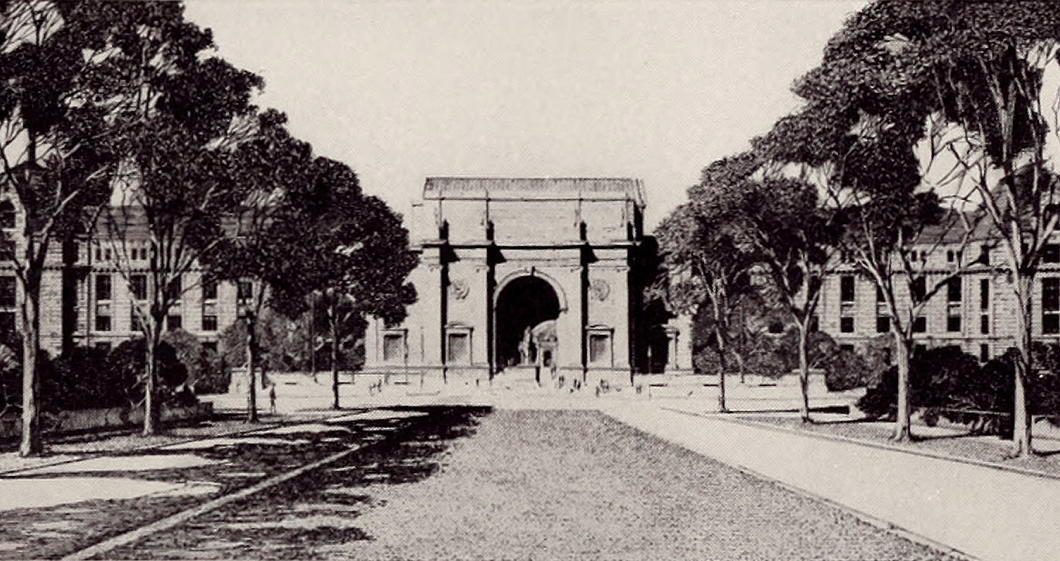

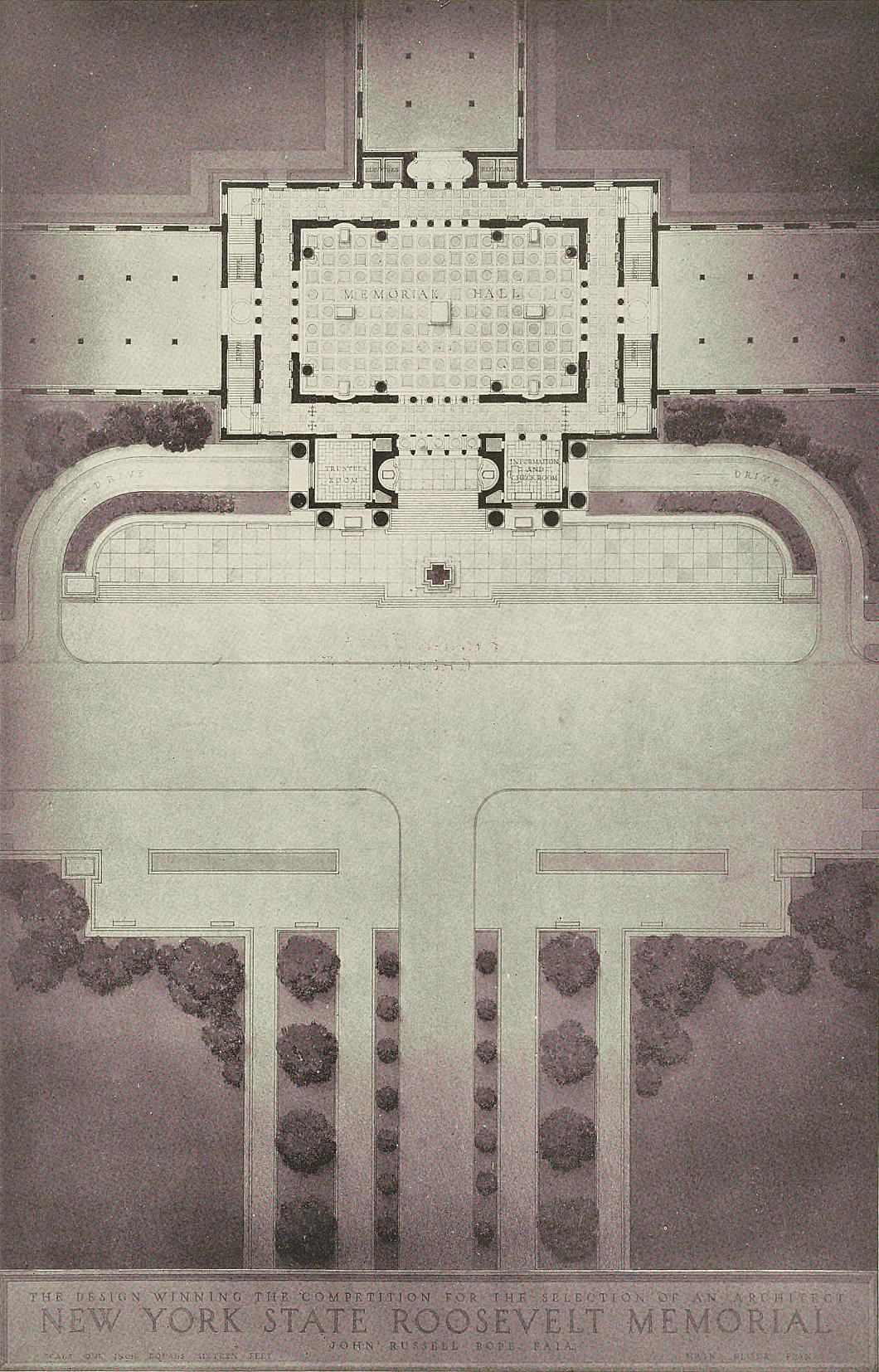

An Approach Not Taken

John Russell Pope’s Unexecuted ‘Museum Walk’

While John Russell Pope won the competition to design the New York State Theodore Roosevelt Memorial currently under attack, not every aspect of his design was executed.

The architect planned for an avenue to be built in Central Park to provide a suitable approach to the American Museum of Natural History and his memorial to the twenty-sixth president.

160 feet wide and 500 feet long, it would feature a broad central lawn flanked by drives and forming an allée of trees. Other versions of the plan have a roadway heading down the middle of the approach.

The idea of this ‘museum walk’ was originally that of Henry Fairfield Osborn, for a quarter-century president of the American Museum of Natural History.

Osborn was also president of the New York Zoological Society — they who run the Bronx Zoo — while his brother was president of the Metropolitan Museum across Central Park.

His son Fairfield also led the NYZS (renamed the Wildlife Conservation Society in 1993) and both père et fils held dodgy pseudoscientific Malthusian views about race and eugenics.

Their family house, Castle Rock, has one of the finest views of West Point across the Hudson and is still in private hands.

For whatever reason — possibly not wanting to redirect the 79th Street Transverse Road through the park that was in the way — Obsborn/Pope’s approach was never built.

It’s a shame as, aside from augmenting the impact of Theodore Roosevelt Memorial, it also would have provided a better vista from the steps of Museum itself.

Theodore Roosevelt

The ancient heresy of iconoclasm claimed a new victim this week: The statue of Theodore Roosevelt which graced the Manhattan memorial dedicated to him at the American Museum of Natural History has been removed at a cost of two million dollars.

The sculpture had attracted the ire of protestors who objected to the inclusion of a Native American and an African by the side of twenty-sixth President of the United States and sometime Governor of New York, which they claimed glorified colonialism and racism.

While the American Museum of Natural History is a private institution, it sits on land owned by the City, and the statue was paid for by the State.

The statue was doomed in June of last year when the New York City Public Design Commission voted unanimously to rip Teddy down.

As the New York Post put it, “He’s going on a rough ride!”

The statue was severed in two this week, with the top half removed and the bottom half following shortly after.

It will be shipped to the Badlands of North Dakota to be displayed as an object in a museum under construction there. (more…)

Abbott’s Gun

Berenice Abbott took a few photographs of New York’s old Police Headquarters viewed from one of the gunsmiths across Centre Market Place.

This street behind the NYPD HQ (which fronts on to Centre Street) became the gunsmiths’ district of Manhattan — policemen being one of the best customers for many of these businesses. (Criminals being another.)

There is something almost mediæval about the giant gun hanging outside, advertising to one and all what the shop had to offer.

Frank Lava, the gunsmith photographed, shut decades ago, but the John Jovino Gun Shop was originally next door before moving around the corner into Grand Street.

Like Lava’s, Jovino’s continued the tradition of hanging a giant gun outside the shop like in Abbott’s photograph.

The John Jovino Gun Shop, founded 1911, chucked in the towel last year when “Gun King Charlie” — owner Charlie Yu — decided the rent was too damn high.

A Metropolitan Christmas

I suppose Whit Stillman’s ‘Metropolitan’ is not strictly speaking a Christmas film but Yuletide is as good a time as any to watch the most Upper-East-Side movie ever to make the silver screen.

It includes a scene (clip above) from the Service of Nine Lessons and Carols at St Thomas, Fifth Avenue, which to my mind is the best carol service in New York. It’s even better when followed by a few drinks at the University Club one block up.

Bronxville’s Coat of Arms

The coat of arms of the Village of Bronxville is a surprisingly handsome design, for which we can thank a gentleman named Lt. Col. Harrison Wright.

The coat of arms of the Village of Bronxville is a surprisingly handsome design, for which we can thank a gentleman named Lt. Col. Harrison Wright.

Known to most as Hal, Wright (1887–1966) was one of those citizens who seemed to have had endless time to devote to those around them. In the Great War he served in a variety of roles and had the pleasure of personally delivering a Packard automobile to General Pershing.

He helped coordinate the village police when its captain’s ill health forced an unexpected retirement and was an active member of the American Legion post.

Wright was also Scoutmaster of Troop 1 and served as the local District Commissioner for the Boy Scouts. In that role he had under his purview a young scout from my old troop — Troop 2, Bronxville — named Jack Kennedy.

During the Second World War, Wright deployed his significant logistical expertise as an officer at the U.S. Army’s New York Port of Embarkation but, with his artistic skills and heraldic interest, he also found time in 1942 to design Bronxville’s coat of arms. (more…)

Staats Long Morris

Everyone knows about Gouverneur Morris, scion of one of New York’s great landowning families and given the moniker ‘penman of the Constitution’. As a signer of the Declaration of Independence his half-brother Lewis Morris III was a fellow ‘founding father’. Less well-remembered is his other half-brother Staats Long Morris (1728–1800).

Their father Lewis Morris II was the second lord of Morrisania, the feudal manor that covered most of what is now the South Bronx and has given its name to the smaller eponymous neighbourhood today.

Staats and Gouveneur owe their distinctive Christian names to the family names of their respective mothers.

Lewis II married Katrintje Staats who provided him with four children. After Katrintje died in 1730, Lewis married Sarah Gouverneur, daughter of the Amsterdam-born Isaac Gouverneur. Sarah’s uncle Abraham was Speaker of the General Assembly of the Province of New York, a role Lewis Morris II eventually filled.

Staats was born at Morrisania on 27 August 1728 and studied at Yale College in neighbouring Connecticut as well as serving as a lieutenant in New York’s provincial militia. He switched to the regular forces in 1755 when he obtained a commission as captain in the 50th Regiment of Foot, moving to the 36th in 1756.

Around that time Catherine, Duchess of Gordon, the somewhat eccentric widow of the third duke, was on the lookout for a second husband and Staats — though American, mere gentry, and ten years her junior — met with her approval. They were married in 1756 and Staats moved in to Gordon Castle to live as the Dowager Duchess’s husband.

‘He conducted himself in this new exaltation with so much moderation, affability, and friendship,’ a newspaper reported in 1781, ‘that the family soon forgot the degradation the Duchess had been guilty of by such a connexion, and received her spouse into their perfect favour and esteem.’

With the Duchess’s patronage, Lieutenant-Colonel Staats raised the 89th Regiment of Foot — “Morris’s Highlanders” — from the Scottish counties of Aberdeenshire and Banffshire though she was extremely cross when her new husband’s regiment was despatched to India where it took part in the siege of Pondichery.

In the event, Morris delayed following his regiment to India, leaving England in April 1762 and remaining there only until December 1763. When the young fourth Duke of Gordon came of age the following year, Staats turned his eyes to America and engaged in land speculation there. In 1768 he and the Duchess even went to visit their purchases in the new world, returning to Scotland in the summer of the following year.

With the fourth Duke’s help, and on the eve of the revolutionary stirrings in North America, Staats was elected to the British parliament for the Scottish seat of Elgin Burghs in 1774. He managed to hold on to it for the next ten years. Was this New Yorker the first Yale man to be elected to Parliament? I can’t find any before him, but more thorough research might prove fruitful.

In 1786 he inherited the manor of Morrisania but with the intervening separation between Great Britain and most of her Atlantic colonies General Morris thought it best to sell it on to his brother Gouverneur.

Though he had rejected a future in the world into which he had been born, Staats did return to North America in a professional capacity in 1797 when he was appointed governor of the military garrison at Quebec in what by then was Lower Canada.

Morris died there in January 1800, but his earthly remains were sent back to Britain where he was interred in Westminster Abbey — the only American to receive that honour.

Articles of Note: 15.I.2021

• Autumn and winter are a time for ghouls and ghosts and eery tales. At Boodle’s for dinner two or three years ago I sat next to the wife of a friend and exchanged favourite writers. I gave her the ‘Transylvanian Tolstoy’ Miklos Banffy, in exchange for which she introduced me to the English writer M.R. James — whose work I’ve immensely enjoyed diving into. The inestimable Niall Gooch writes about Christmas, Ghosts, and M.R. James, as well as pointing to Aris Roussinos on how Britons’ love for ghostly tales is a sign of (little-c) conservatism.

• There can be few figures in English history more ridiculous than Sir Oswald Mosley. But the Conservative MP who became a Labour government minister and then British fascist führer-in-waiting was also forceful in his condemnation of the savagery unleashed by the Black-and-Tans. In 1952 a local newspaper in Ireland announced that Sir Oswald and Lady Mosley “charmed with Ireland, its people, the tempo of its life, and its scenery” had taken up residence at Clonfert Palace in Co. Galway. “Sir Oswald,” the paper noted with amazing restraint, “was the former leader of a political movement in England.” Maurice Walsh presents us with the history of Mosley in Ireland.

• The death of the late Lord Sacks, Britain’s former Chief Rabbi, was the subject of much lament. Rabbi Sacks was obviously no Catholic, but his intellect, frankness, and generosity were much appreciated by Christians. Sohrab Ahmari, one of the editors at New York’s most ancient and venerable daily newspaper, offers a Catholic tribute to Jonathan Sacks.

• “Education, Education, Education” has become a mantra in the past quarter-century and while there is a point there’s also a certain error of mistaking the means to an end for the end itself. After all, in the 1930s Germany was the most and highest educated country in the world. At Tablet, probably America’s best Jewish magazine, Ashley K. Fernandes explores why so many doctors became Nazis.

• Fifty years ago the great people of the state of New York rejected both the Republican incumbent and a Democratic challenger to elect the third-party Conservative candidate James Buckley as the Empire State’s senator in Washington. At National Review Jack Fowler tells the gleeful story of the unique circumstances that brought about this victory for Knickerbocker Toryism and how Mr Buckley went to the Senate.

Septuagesimo Uno

Septuagesimo Uno is often believed to be the smallest park under the purview of the Parks Department of the City of New York. It’s not. (By my reckoning, the Abe Lebewohl Triangle where Stuyvesant Street meets 10th Street near St-Mark’s-in-the-Bowery is the smallest.)

Though not the smallest, this park on West 71st Street is charming all the same. The site was acquired in 1969 thanks to Mayor Lindsay (or “Lindsley” as my maternal great-grandfather always mispronounced his name) and his Vest Pocket Park initiative. The small building on the lot was condemned and demolished by the City though it was only handed over to the Parks Department in 1981.

Originally known as the “71st Street Plot”, Parks Commissioner Henry Stern thought the name was too boring so rechristened it under the Latin moniker Septuagesimo Uno — Latin for ‘seventy-one’. (more…)

Arms and the Man

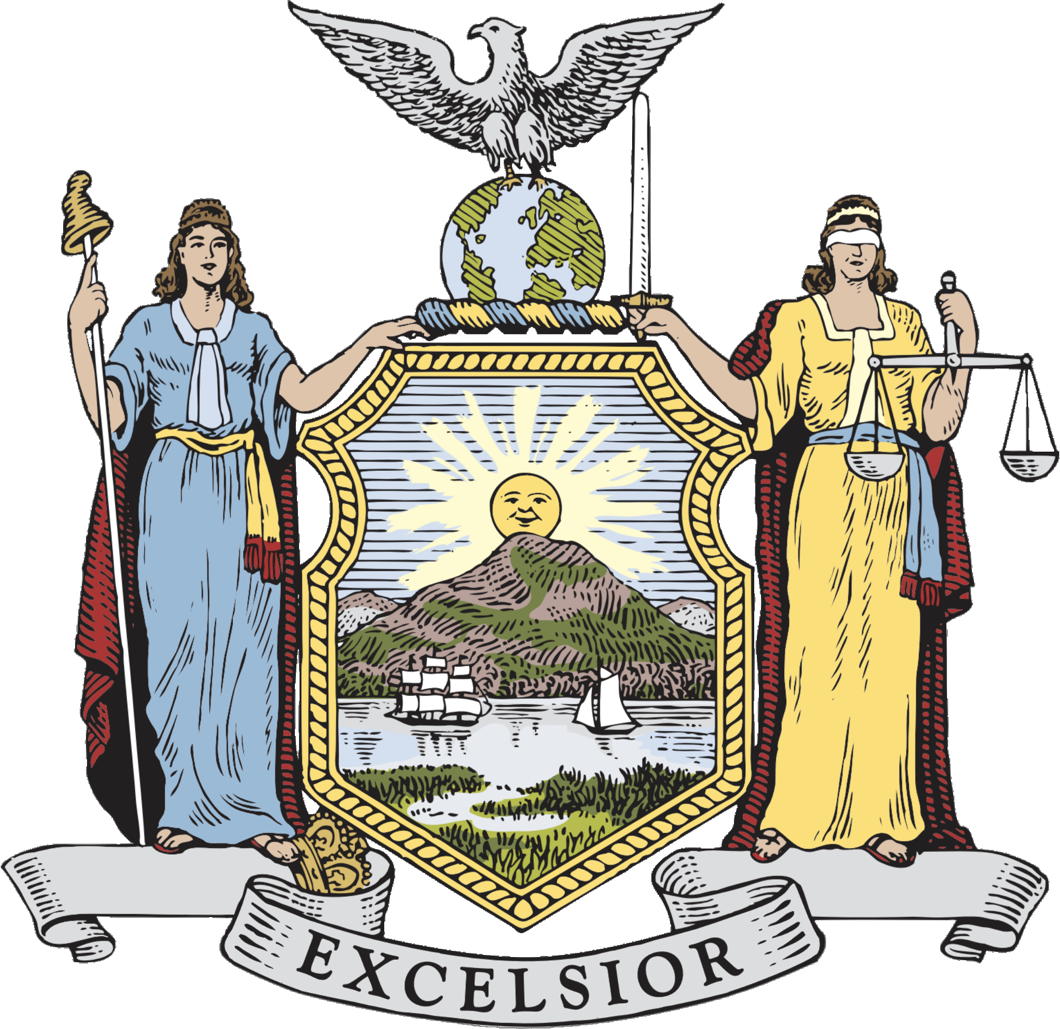

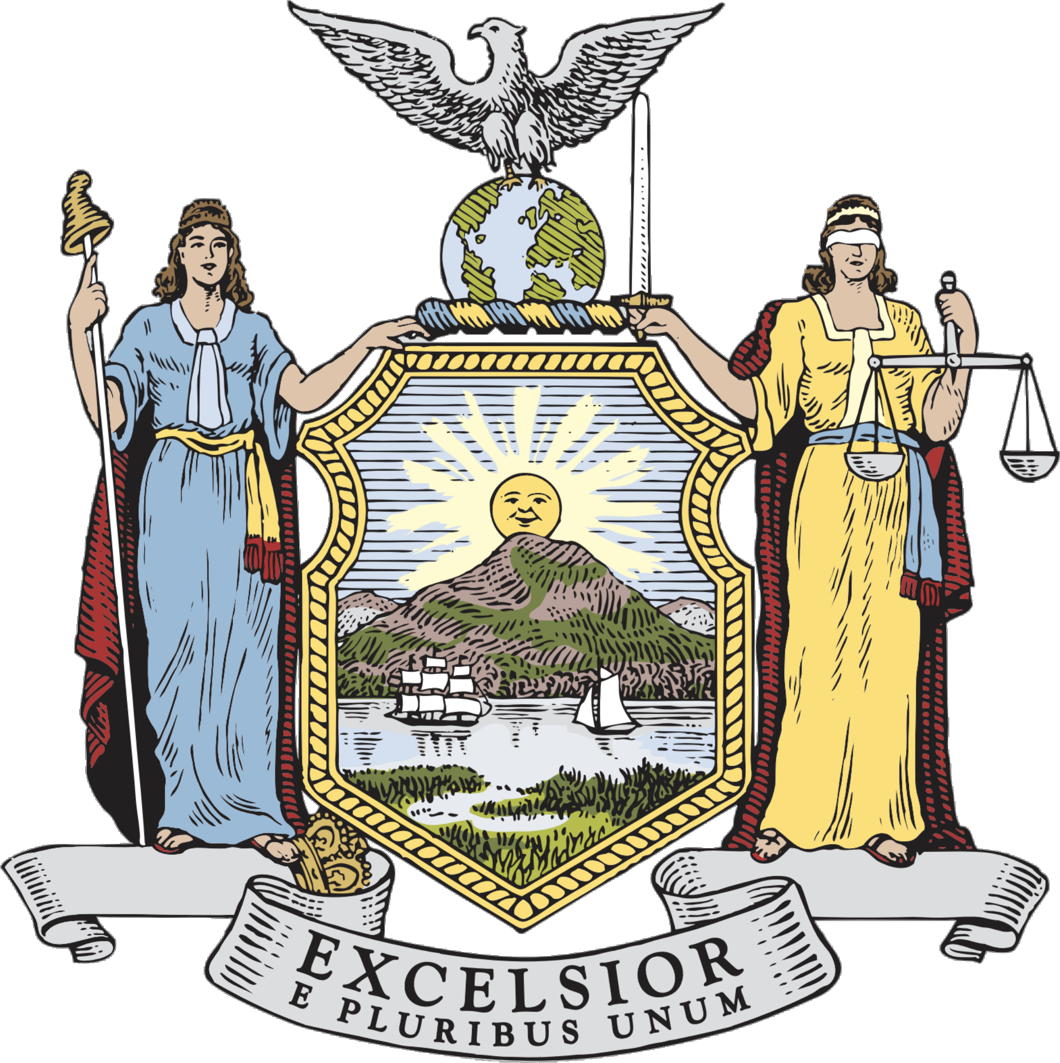

GOVERNOR CUOMO — is there anything that man won’t fiddle with? Is there nothing that can escape his grasping hands? Are we to suffer from the incessant interference of this megalomaniac forever?

The latest trespass His Excellency has committed is to encroach upon the very sacred symbols of the Empire State itself: our beloved coat of arms — and, by extension, the flag which also bears it aloft.

Gaze upon its beauty, for you will see it fade. Azure, in a landscape, the sun in fess, rising in splendour or, behind a range of three mountains, the middle one the highest; in base a ship and sloop under sail, passing and about to meet on a river.

This beautiful device was adopted by the very first Assembly and Senate of the State of New York back in 1778, having been designed a year earlier. It has remained substantially unchanged since the 1880s until Governor Cuomo in one of his fits of fancy decided to sneak a change via the state budget, of all things.

“In this term of turmoil, let New York state remind the nation of who we are,” Governor Cuomo said in his State of the State address in January of this year. “Let’s add ‘E pluribus unum’ to the seal of our state and proclaim at this time the simple truth that without unity, we are nothing.”

Why the national motto should be interjected into the state flag when we have our own motto is beyond me. Rather than introduce a bill that would allow an open debate on the matter, the Governor decided to sneak it into the state budget. This passed in April, so the coat of arms, great seal, and flag of the state of New York have all now been altered to include the superfluous words.

That said, I have a sneaking suspicion the change might be honoured more in the breach than in the observance. Flag companies doubtless have a large back supply of pre-Cuomo flags to shift and customers are rarely up to date on matters vexillological and heraldic. I suspect that the next time you float down Park Avenue and see the giant banners fluttering from corporate headquarters very few will have updated their state flag.

Onze Grootste President

The London Residence of President Martin van Buren

Transacting some business in March before the plague struck us here in London I found myself with a moment to spare and made a brief pilgrimage to No. 7, Stratford Place. It was in this handsome townhouse that Martin van Buren, the first New Yorker to ascend to the chief magistracy of the American Republic, had his residence when he served as the United States’s minister to Great Britain in 1831.

While I often claim that Calvin Coolidge was America’s greatest president in reality my chief devotion in that contest is to the Little Magician himself, the Red Fox of Kinderhook.

Among the many characteristics of this esteemed Knickerbocker is that English was not his native language and throughout his career as a democratically elected politician he spoke with a thick Dutch accent. To his wife, he spoke almost entirely in Dutch.

Jay Cost and Luke Thompson’s Constitutionally Speaking podcast at National Review recently released the first of a two episodes about van Buren and while I’m no fan of podcasts in general this was worth listening to.

One of the factors Cost and Thompson highlight is the utility of the party machine structures of the day in solidifying the practice of America’s democracy and acting as a vehicle of accountability, something too little appreciated by most later observers of the period.

We keen Kinderhookers and Van Buren Boys await the second instalment with anticipation.

Shamefully I have not yet made the pilgrimage to Kinderhook itself, but it’s pleasing to learn that the dominie of the Dutch Reformed Church is a graduate of the greatest university in the southern hemisphere.

How Our Ancestors Built

The Hudson River Day Line Building in Albany

The visitor arriving at Albany, the capital of the Empire State, might be forgiven for presuming the riparian French gothic mock-chateau he first views is the most important building in town.

Built as the headquarters of the Delaware & Hudson, a canal company founded in 1823 that successfully transitioned into the railways, the chateau now houses the administration of the State University of New York. (Indeed, the Chancellor once had a suitably grandiose apartment in the southern tower.) That building, with its pinnacle topped by Halve Maen weathervane, is worthy of examination in its own right.

But next to this towering edifice is an altogether smaller charming little holdout: the ticket office of the Hudson River Day Line.

In the nineteenth century the Hudson River Valley was often known as “America’s Rhineland” and travel up and down the river was not just for business but also for the aesthetic-spiritual searching that inspired the Hudson River School of painters.

The Day Line’s origins date to 1826 when its founder Abraham van Santvoord began work as an agent for the New York Steam Navigation Company. Van Santvoord’s company merged with others under his son Alfred’s guidance in 1879 to form the Day Line. (more…)

The Rensselaer Window

The patroonship of Rensselaerswyck was erected in 1630 giving its patroon, Kiliaen van Rensselaer, feudal powers over a large parcel of land on the banks of the Hudson River. Despite exercising a strong influence on the growth and development of New Netherland and the Hudson Valley, Kiliaen never actually stepped foot in the new world but kept close control of his domain from across the ocean in Amsterdam.

Jan Baptist was Kiliaen’s second surviving son, and served as director at the ‘colony’ as it was often known from 1652 to 1658. He commissioned Evert Duyckinck to make this painted-glass window displaying his coat of arms in 1656 and gave it to the Dutch Reformed Church in Beverwyck (today’s Albany).

While the congregation still exists — and celebrated its 375th anniversary in 2017 — the original church was demolished in 1805 and the window moved to the Van Rensselaer Manor House which itself survived til 1890 before facing the wrecking ball. The window was preserved and was left to the Metropolitan Museum of Art through the 1951 bequest of Mrs J. Insley Blair and while well documented it does not appear to be on display at the moment.

The patroonship itself was converted into a manorial lordship by the English authorities after they took over and survived until it was broken up amongst relatives after the death of Stephen van Rensselaer III in 1839.

This last great patroon had proved an indulgent lord and the efforts of his inheritors to claim uncollected back rents led to the 1839-1845 “Helderberg War” or “Anti-Rent War” of tenants revolting against the system. The great landholders, seeing the end was nigh, were convinced to sell up and in 1846 the state of New York adopted a new constitution abolishing feudal tenure. The era of patroonships and manors in the Hudson Valley had come to an end.

Neo-Classical New York

The dome of the old Police Headquarters Centre Street in New York.

More Dutch Flags of New York

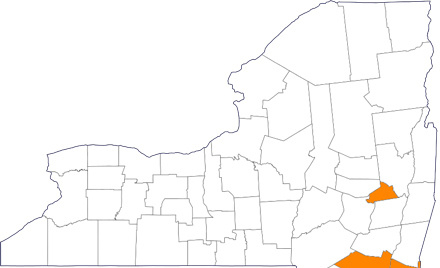

Areas shaded in orange are the counties of New York with Dutch-influenced flags

Natives and outsiders alike are often surprised when it’s pointed out just quite how much New York continues to be influenced by its Dutch foundation to this day, even though Dutch rule ended in the seventeenth century.

Previously I explored a number of local or regional flags in the state of New York that show signs of Dutch influence: those of the cities of New York and Albany, the Boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens, and the counties of Westchester, Nassau, and Orange.

I’ve since found a few more counties to add to our survey of Dutch flags in the Empire State.

Dutchess County

One of the original counties of New York established in 1683, Dutchess retains the archaic spelling of Mary of Modena’s title while she was Duchess of York. Appropriately for a county that was until very recently largely agricultural, the county seal depicts a sheaf and plough, and sits on the county’s flag with its horizontal tricolour of orange, white, and blue.

Ulster County

Across the Hudson from Dutchess County is Ulster, another of New York’s first counties. Its handsome seal features an early farmer wielding a sickle in front of a sheaf and a farmhouse, with the year of the county’s erection proudly included. The Dutch had begun to trade here as early as 1614, and the village of Wiltwijck was given municipal status by Peter Stuyvesant in 1663. Wiltwijck became Kingston in 1669 and remains a very handsome town today.

Schenectady County

The county of Schenectady is of later origin, 1809, and became industrialised in the latter half of the nineteenth century — the General Electric Company was founded here in 1892. Like Ulster and Dutchess, the county flag is just the seal displayed on an orange-white-blue tricolour.

The seal is a relatively boring depicting of crossed swords combined with the scales of justice, but on the flag it is depicted with a locomotive, canal boat, broomhead, and lightning bolt and atom.

St Nicholas, Our Patron

As by now you are all well aware, today is the feast of Saint Nicholas, the patron-saint of New York. His patronship (patroonship?) over the Big Apple and the Empire State date to our Dutch forefathers of old – real founding fathers like Minuit, van Rensselaer, and Stuyvesant, not those troublesome Bostonians and Virginians who started all that revolution business.

Despite being Protestants of the most wicked and foul variety, the New Amsterdammers and Hudson Valley Dutch maintained their pious devotion to the Wonder-working Bishop of Myra and kept his feast with great solemnity.

After New Netherland came into the hands of the British (and was re-named after our last Catholic king) the holiday continued to be celebrated by the Dutch part of the population, and was greatly popularised in the early nineteenth century by the publication of a curious volume entitled A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty which purported to be by one Diedrich Knickerbocker.

In fact it was by Washington Irving, the first American writer to make a living off his pen, who did much to popularise St Nicholas Day in New York as well as to revive the celebration of Christmas across the young United States.

While, aside from hearing Mass and curling up with a clay pipe and a volume of Irving (being obsessive, I have two complete sets) here are a few links that shed some light on New York’s heavenly protector.

Historical Digression: Santa Claus was Made by Washington Irving

New-York Historical Society Quarterly: Knickerbocker Santa Claus

The History Reader: The 18th Century Politics of Santa Claus in America

The New York Times: How Christmas Became Merry

The Hyphen: Thomas Nast’s Illustrations of Santa Claus

– plus: Santa Claus and the Ladies

National Geographic: From Saint Nicholas to Santa Claus

Previously: Saint Nicholas (Index)

Knickerbocker Spires

Before the age of the skyscrapers, New York’s church spires dominated the horizon and dwarfed their neighbours just like in the medieval towns and cities of the old world — as this photo from the 1900s shows.

Here St Patrick’s Cathedral holds court, with the St. Nicholas Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church poking up a few blocks down Fifth Avenue.

Slightly north on that same boulevard sits the grand renaissance palazzo of the University Club, with the spire of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church poking up behind it.

Inside Governors Island

This intriguing little island in New York Harbour has always held something of a fascination for me — viz. articles previous on the subject. Aside from its interesting history there is the matter of the complete lack of foresight in ending its military use as well as the failure to imagine a future use suitable to its history and, if the word is not hyperbole, majesty.

Gothamist recently featured a new peek inside some of the abandoned buildings on Governors Island, a mere selection of which are reproduced here. (more…)

The Governor’s Room

Pursuant to my post of John Bartlestone’s photographs of City Hall, I came across this photo the other day and it reminded me that this is still one of my favourite rooms in all New York. There’s something about that particular shade of green. I previously wrote about this suite of three rooms in 2006.

The above photo is by Ramin Talaie while below, in 2010, Mayor Bloomberg inspects a city flag being sent to a New Yorker serving in Afghanistan as reported by the Daily News.

The late & much-missed New York Sun also reported on the portraits hanging in City Hall in 2008.

City Hall

These images of City Hall show the superb skill and eye for detail of the architectural photographer John Bartelstone — a licensed architect in his own right — and date from the completion of the most recent set of renovations in 2015.

Church of the Intercession

The huge and spacious interior of the Church of the Intercession, New York. One of Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue’s masterpieces; so much so that he decided to be interred in the north transept of the church.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories