Netherlands

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Vote AR

The lush and verdant tree formed in the shape of the Netherlands grows from deep roots spelling out ‘AR’, the name of the main Protestant party — once led by Abraham Kuyper.

As Kamps and Voerman point out in their book on posters from the Dutch Christian-democratic tradition (in print / online), this poster is a “rather complicated allegorical representation”.

Amsterdam

Is die Amsterdamse stadsargitektuur die mees hemels in die wêreld? Winkels, huise, alles baie aangenaam. Burgerlik. (Ek moet teruggaan.)

Die Nederlanders het ’n samelewing met ’n semi-republikeinse mentaliteit maar met (amper) al die geseënde vrugte van ’n koninkryk. Beste van alle moontlike wêrelde…

Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

Caro had been a Nieman Fellow at Harvard studying urban planning and land use when he came up with the idea for the book. He thought it would take him nine months, but extensive research and over five-hundred in-person interviews meant it took eight years to complete.

Caro then started working on his study of Lyndon Baines Johnson, the first volume of which emerged in 1982 and the fifth (and final?) one he is still working on. (At the end of the fourth, LBJ had just become president.)

But where does he write? Christopher Bonanos of New York magazine finds out:

It’s an ageless space, one where it could be last week or 1950 inside, matter-of-fact and utilitarian. A couple of bookcases, a plywood work surface, corkboard with outlines tacked up, an old brass lamp, an underworked laptop for emails, a Smith-Corona typewriter. The desk chair is hard wood with no cushion. There’s a saltshaker next to the pencil cup for when Ina brings a sandwich out at midday. The desk has a big half-moon cutout, same as the one back in New York, so he can rest his weight on his forearms and ease his bad back. That arrangement was recommended by Janet Travell, the doctor who grew famous for prescribing John F. Kennedy his Boston rocker. She, with Ina, is a dedicatee of The Power Broker.

He bought the prefab shack, he says, from a place in Riverhead for $2,300, after a contractor quoted him a comically overstuffed Hamptons price to build one. “Thirty years, and it’s never leaked,” he says. This particular shed was a floor sample, bought because he wanted it delivered right away. The business’s owner demurred. “So I said the following thing, which is always the magic words with people who work: ‘I can’t lose the days.’ She gets up, sort of pads back around the corner, and I hear her calling someone … and she comes back and she says, ‘You can have it tomorrow.’”

Does he write out here every day? “Pretty much every day.” Weekends too? “Yeah.” Does he go out much while he’s on the East End? “We have two friends who live south of the highway, and I said to Ina, aside from them, I’m not going this year.” There are other writer friends nearby in Sag Harbor, and they get together, but at this age, Caro admits a little sadly, they’re thinning out. He’ll be 89 this fall.

■ George Grant is a still-underappreciated giant of political thinking in the English-speaking world. He is too little known outside his native Canada, which he sought to defend from the undue overwhelming influence of its sparkling and glamourous southern neighbour. Next year marks the sixtieth anniversary of his Lament for a Nation.

Of all people, a research fellow at Communist China’s Institute for the Marxist Study of Religion — George Dunn — has written a thoughtful introductory overview of Grant’s life and thinking: George Grant and Conservative Social Democracy in Compact.

■ Katja Hoyer mused on an overlapping theme in a recent Berliner Zeitung column which she has helpfully presented in English as well:

A diplomat close to the SPD recently told me that he couldn’t understand why working-class people in particular voted for the AfD. Things weren’t so bad for them, after all. I didn’t bother pointing out that rampant inflation, high energy prices and rising rents have had a hugely detrimental effect on the living standards of people with low and middle incomes because his analysis completely misses the point.

Germany’s working-class voters, Katja argues, feel forgotten by the parties founded to represent them.

■ Since the fall of the Berlin Wall — and earlier in Angledom — political conservatism has effectively been taken over by economic liberalism.

This has denied the centre-right from learning from and deploying useful experience from outside liberalism, with the wisdom of figures as varied as Benjamin Disraeli, Giorgio La Pira, Charles de Gaulle, and Thomas Playford essentially ignored or sidelined.

Kit Kowol’s new book Blue Jerusalem: British Conservatism, Winston Churchill, and the Second World War explores the visionary side of wartime Conservatism. Dr Francis Young offers his take on Tory utopias in The Critic.

■ From a similar era, Andrew Ehrhardt writes at Engelsberg Ideas on Ernest Bevin and the moral-spiritual dimension of British foreign policy.

■ Our friend Samuel Rubinstein has studied at Oxford, Leiden, and the Sorbonne — technically the oldest universities in their three respective countries (although we all know that Leuven is in fact the doyen of Netherlandish academies).

Sam offers an incredibly interesting comparison of the experiences of these three institutions in a humble essay on his Odyssean education:

I arrived in Leiden, armed with my phrase-book, with some ambitions of learning Dutch. The first blow came at the Starbucks in the train station, when the barista answered my Ik wil graag in English without hesitating. The second came the following day when I tried again, at a different café – only this time it seemed that the barista (Spanish? Italian?) didn’t know much Dutch either: even the natives were placing their orders in English. So I gave up – save one hobby, reading Huizinga in the original. I got myself an attractive coffee-table edition of Herfsttij and managed a page or so a day, strenuously piecing it together from my English, German, and smattering of Old English. I still haven’t the faintest idea how to pronounce any of it.

■ And finally, those of us who love Transylvania will enjoy Toby Guise’s summary of the Fifth Transylvanian Book Festival in The New Criterion.

Articles of Note: 13 March 2024

My then-flatmate was getting married the next day and much pottering-about sorting things was required but the idiosyncratic beauty of this building captured my imagination — part Norman, part Moorish. I was almost insulted that I hadn’t come across it in any of my bookish explorations.

The historian Edmund Harris covers Chideock in his lusciously illustrated post on Recusancy in Dorset and the ‘other tradition’ of Catholic church-building.

■ Generations ago it was said that the three institutions no British politician dared offend were the trade unions, the Catholic Church, and the Brigade of Guards. In 2020s Britain there is only one caste which must always be obeyed: the ageing, moneyed homeowners.

Not only do these “NIMBYs” (“Not In My Back Yard”) jealously guard their freeholds, they do whatever they can to prevent more houses being built to guard the value of their prize possessions, vastly inflated by a combination of lacklustre housebuilding and irresponsible leap in migration. As old people vote and young people don’t — and when they do, vote badly — few sensible people can find a way out of this quagmire.

It might be worth looking to the Mediterranean, where Tal Alster tells us How Israel turned urban homeowners into YIMBYs.

■ It’s disappointingly rare to see intelligent outsiders give a considered impression of the current state of play in the Netherlands — that’s Mother Holland for us New Yorkers. Too often commentators in English are either rash cheerleaders for the hard right or bien-pensant liberals eager to castigate and chastise. Both rush to judgement.

What a rare diversion then to read Christopher Caldwell — the only thinking neo-con? — attempt to explore and explain the success of Geert Wilders in the recent Dutch elections.

■ One in ten of Lusitania’s inhabitants are now immigrants, and this discounts those — many from Brazil and other former parts of the once-world-spanning Portuguese empire — who have managed to acquire citizenship through various routes.

Ukrainian number-plates are now frequently be seen on the roads of Lisbon, as far in Europe as you can get from Big Bad Uncle Vlad.

Vasco Queirós asks: Who is Portugal for?

■ Speaking of world-spanning empires, in true andrewcusackdotcom fashion, we haven’t had enough of the Dutch — but we have had enough of their wicked wayward heresies.

Historian Charles H. Parker explores the legacies of Calvinism in the Dutch empire.

■ The City of New York itself is the best journalism school there is. Jimmy Breslin dropped out of LIU after two years, eventually taking up his pen. Pete Hamill left school at fifteen, apprenticed as a sheet metal worker, and joined the navy.

William Deresiewicz argues that a dose of working-class realism can save journalism from groupthink.

■ The New Yorker tells us how a Manchester barkeep found and saved a lost (ostensible) masterpiece of interwar British literature.

■ Our inestimable friend Dr Harshan Kumarasingham explores David Torrance’s history of the first Labour government on its hundredth anniversary.

■ And finally, one for nous les normandes (ok, ok, celto-normandes): Canada’s National Treasure David Warren briefly muses that the Norman infusion greatly refined Anglo-Saxon to give us the superior English tongue we speak today.

‘The first great commercial people’

[…]

And it was for this same reason that they were unable to maintain that supremacy: for all its busy tenacity, their effort lacked a higher inspiration and, therefore, real vitality. Numerically, too, they were too few to be able for long to subdue and batten on half the world. It was the same maladjustment which turned Sweden’s taste of world-power into an episode: the national basis was too small.

There is no doubt that the cultural level was at that time higher in Holland than in the rest of Europe. The universities enjoyed an international reputation. Leyden in particular was accounted supreme in philology, political science, and natural philosophy.

It was in Holland that Descartes and Spinoza lived and worked, as also the famous philologists Heinsius and Vossius, the great jurist-philosopher Grotius, and the poet Vondel, whose dramas were imitated all the world over.

The Elzevir dynasty dominated the European book trade, and the Elzevir publications — duodecimo editions of the Bible, the classics, and prominent contemporaries— were appreciated in every library for their elegant beauty and their correctness.

At a time when illiteracy was still almost universal in other lands, nearly everyone in Holland could read and write; and Dutch culture and manners were rated so high that in the higher ranks of society a man’s education was considered incomplete unless he could say that he had been finished off in Holland, “civilisé en Hollande”.

The colonising activities of the Dutch set in practically with the new century, and fill the first two-thirds of it. They quickly gained a footing in all quarters of the world.

On the north-east coast of South America they took possession of Guiana, and in North America they founded the New Amsterdam which was later to become New York: centuries afterwards the Dutch or “Knickerbocker” families still constituted a sort of aristocracy.

They spread themselves over the southern-most tip of Africa, where they became known as Boers, and imported from there the excellent Cape wines.

One whole continent bore their name: namely, New Holland — the later Australia — round which Tasman was the first to sail. Tasman did not, however, penetrate to the interior, but supposed Tasmania (which was named after him) to be a peninsula.

The Dutch were also the first to land on the southern extremity of America, which was named Cape Horn (Hoorn) after the birthplace of the discoverer.

Their greatest acquisitions, however, were in the Sunda islands: Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Celebes, and the Moluccas all came into their possession.

Extending out to Ceylon and Further India, by 1610 they had already founded their main base, Batavia, with its magnificent trade-buildings. In fact they ruled over the whole Indian archipelago. For a time they even held Brazil.

With all this, they never, in the true sense of the word, colonised, but merely set up trading centres, peripheral depots, with forts and factories, intended only for the economic exploitation of the country and the protection of the sea routes.

Nowhere did they succeed in making real conquests; for these, as we said before, they had not the necessary population, nor had they, as a purely commercial people, the smallest interest in doing so.

Their chief exports were costly spices, rice, and tea. To the last-named Europe accustomed itself but slowly. At the English Court it first appeared in 1664 and was not considered very palatable — for it was served as a vegetable. In France it was known a generation earlier, but even there it had to make its way slowly through a mountain of prejudice.

Moreover, its consumption was limited by the Dutch themselves, who, having a monopoly to export it, raised the prices to the level of sheer extortion. This was in fact their normal procedure throughout, and they did not shrink from the most infamous practices, such as the burning of large pepper and nutmeg nurseries and the sinking of whole cargoes.

Their home production, too, dominated the European market with its numerous specialities. All the world bought their clay pipes; a fishing fleet of more than two thousand vessels supplied the whole of Europe with herrings; and from Delft, the main seal of the china industry, the popular blue and white glazed jugs, dishes, and table implements, tiles, stoves, and fancy figures went forth to all points of the compass.

One Dutch article that was in universal demand was the tulip bulb. It became a sport and a science to breed this gorgeous flower in ever new colours, forms, and patterns. Immense tulip farms covered the ground in Holland, and amateurs or speculators would pay the price of an estate for a single rare fancy breed.

The get-rich-quick people threw themselves into the “option” game: that is, they sold costly specimens, which often existed only in imagination, against future delivery, paying only the difference between the agreed price and the price quoted on settling day. It is indeed the Dutch who may claim the dubious honour of having invented the modem stock-exchange system with all the manipulative practices that we know today.

The great tulip crash of 1637, which was the result of all this bubble trading, is the first stock-exchange collapse in the history of the world. The shares of the Dutch trading companies, in particular the East Indian (floated in 1602) and the West Indian (1621), were the first stocks to be handled in the stock-broking manner (their par value speedily tripled itself, and the dividends rose to twenty per cent and higher); and the Amsterdam Exchange, which ruled the world, became the finishing school for the game of “bull” and “bear.”

Then, too, during the first half of the seventeenth century, the Dutch were Europe’s sole middlemen: their mercantile marine was three times as big as that of all other countries.

And although — or indeed because — the whole world depended on it, there arose a bitter hatred against it (contrasting strangely with the extravagant admiration accorded to their manners and comforts) which was intensified by the brutal and reckless extremes to which they went in maintaining their advantage. “Trade must be free everywhere, up to the gates of hell,” was their supreme article of faith.

But by free trade they meant freedom for themselves — in other words, a ruthlessly exploited monopoly. This was also the kind of freedom that Grotius meant when in his famous treatise on international law, Mare liberum, he stated that the discovery of foreign countries does not in itself give right of possession, and that the sea by its very nature is outside all possession and is the property of everyone.

But as the sea was in fact in the possession of the Dutch, this liberal philosophy was no more than the historical mask for an economic terrorism.

In this wise the “United States” became the richest and most prosperous country of Europe. There was so much money that the rate of interest was only two to three per cent.

But although naturally the common people lived under far better conditions than elsewhere, the great profits were made by a comparatively small oligarchy of hard, fat money-bags, the so-called “Regent-families” who were in almost absolute control — since they filled all the leading posts in the government, the judicature, and the colonies — and looked down on the common man, the “Jan Hagel,” as contemptuously as did the aristocrats of other countries.

Opposed to them was the party of the Oranges, who by an unwritten law held the hereditary town governorships; their aim was indeed a legitimate monarchy, but they were nevertheless far more democratic in their ideas than the moneyed class, and were therefore beloved of the people. The best talent, military and technical, gathered about them. The first strategists of the age were on their staff. They nurtured a generation of virtuosi in siege warfare, privateering, artillery, and engineering science. The water-network created by them, which covered the whole of Holland, was considered a world marvel. They were masters, too, of diplomacy. …

The Other Modern in Jewish Amsterdam

Jacobus Baars’ Synagoge Oost, Linnaeus Street

There were few places where architecture’s competing forms of modernism overlapped more than the Netherlands in the 1920s. Traditionalists like Kropholler, De Stijl’s Oud, Rationalists like van der Vlugt and Duiker, and the versatile Dudok built alongside the work of the capital’s eponymous ‘Amsterdam school’ style.

The influence of the great Dutch architect Pierre Cuypers — Holland’s Pugin — might be inferred as the progenitors of the Amsterdam school (De Klerk, van der Mey, and Kramer) all studied or worked in the firm of Cuypers’ nephew Eduard.

The Dutch capital’s take on the brick expressionism originated among its Hanseatic neighbours but was sufficiently distinct to merit its own name. Architect Jacobus Baars (1886-1956) deployed the style to great effect in the work he did for Amsterdam’s then-flourishing Jewish community.

Baars designed the 1928 Synagoge Oost (East Synagogue) on Linnaeusstraat (Linnaeus Street) in the Transvaalbuurt neighbourhood that was developed in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Dutch sympathies in the then-still-recent Anglo-Boer War are obvious from the naming of local streets and squares (and, indeed, the district) after Afrikaner places, battles, and statesmen.

The architect placed the building at an angle so that the entrance could face on to Linnaeusstraat while the holy ark containing the Torah scrolls faced Jerusalem, skilfully filling in the rest of the site with clergy and school structures ancillary to the sanctuary and congregation. (more…)

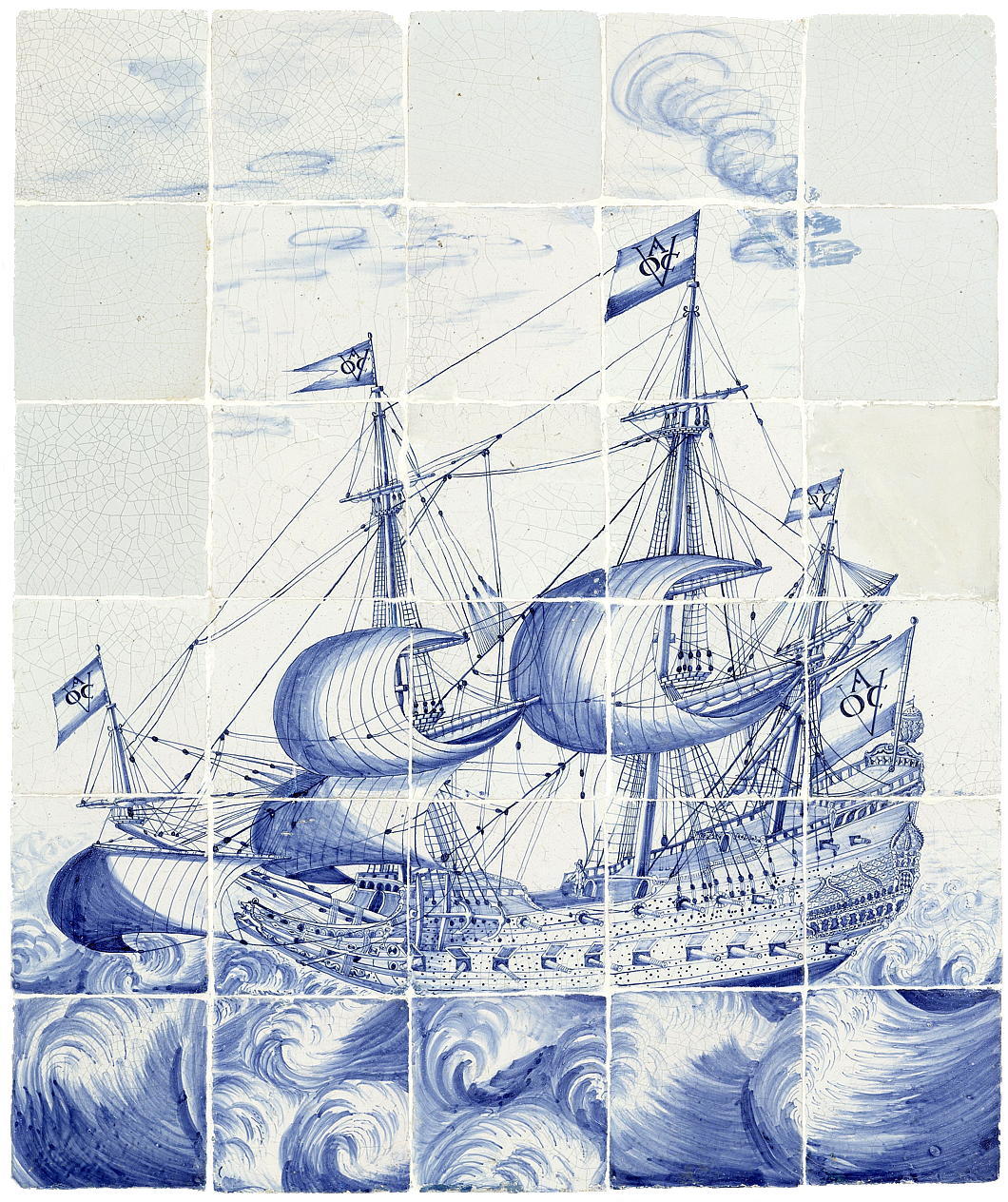

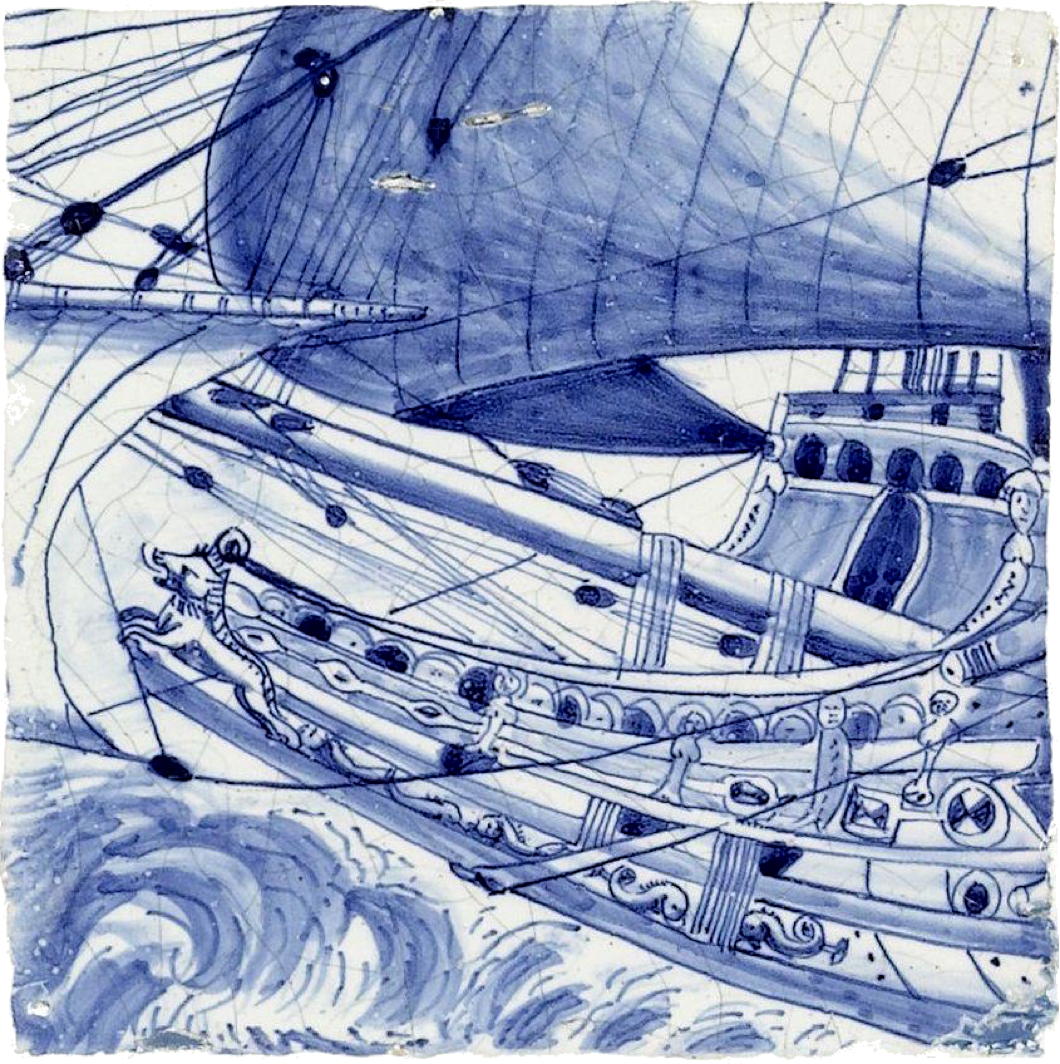

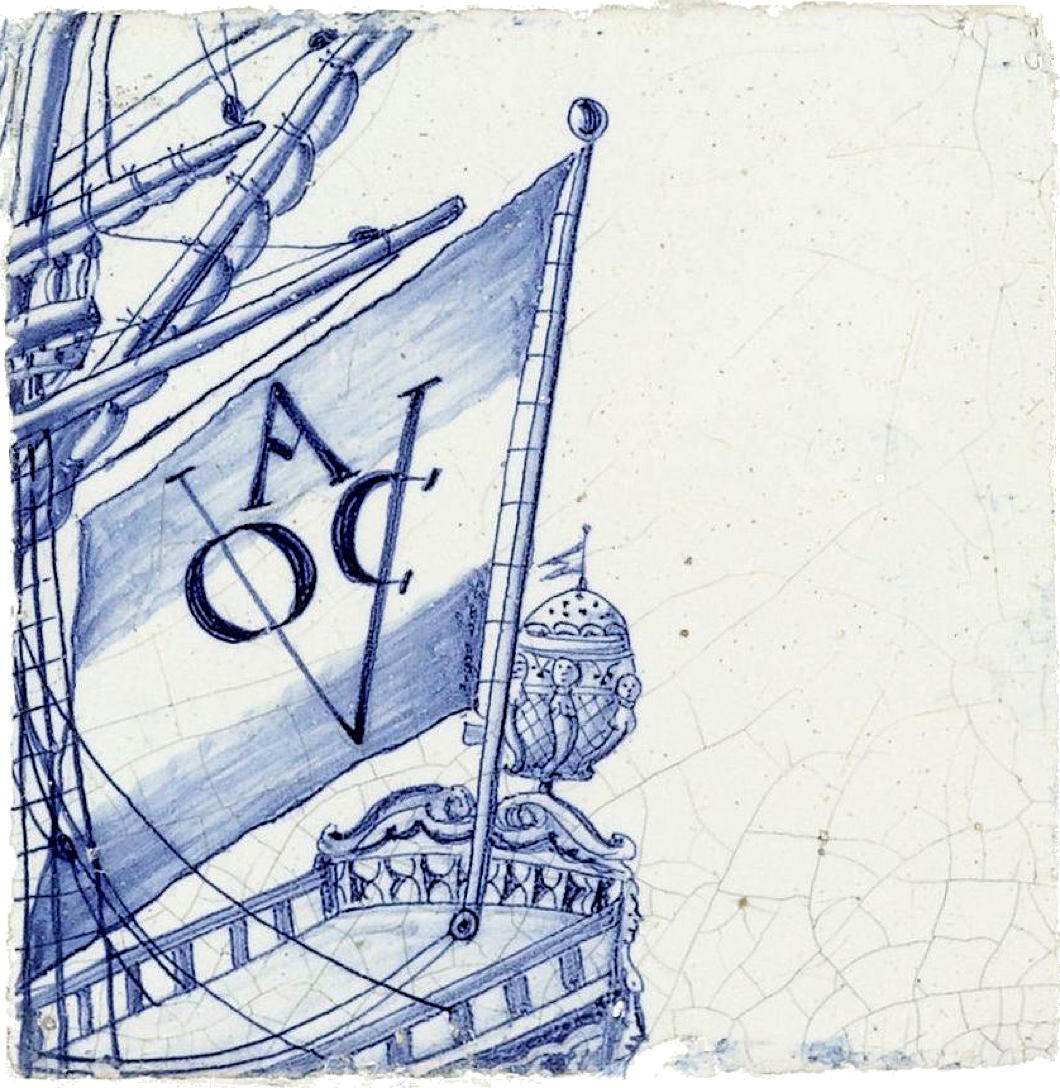

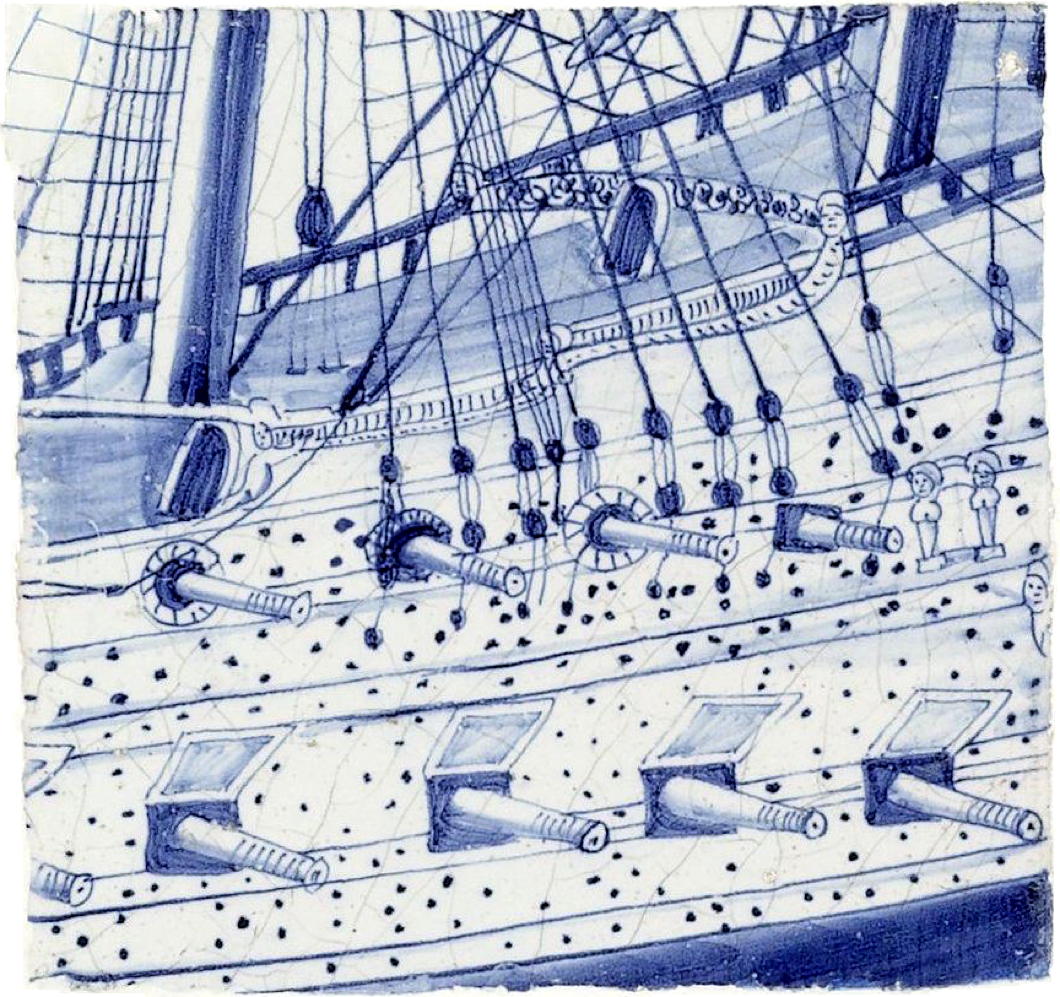

An East Indiaman

English sea-goers and merchants commonly referred to any ship of the Dutch VOC (or of other similar companies) as an ‘East Indiaman’.

The Nicolaasjaar

Catholic Amsterdam Proclaims a Year of Saint Nicholas

A TINY RELIC of Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker has provided an excuse for Amsterdam Catholics to organise a whole year of festivities dedicated to the holy man and his legacy. The Basilica of St Nicholas stands just across from Centraal Station, gateway to the Dutch capital for so many visitors, and the parish has received as a gift the relic from the Benedictine abbey of St Adalbert’s in Egmond.

The tiny sliver of St Nicholas’s rib was enshrined in the Basilica at a special Mass opening the Nicolaasjaar on the eve of the saint’s feast in December. Bishop Jan van Burgsteden presided and prayers were also offered for HKH Princess Catharina-Amalia whose eighteenth birthday fell days later on 7 December.

The opening of the year met with wide coverage in the media, with even the website of the city proclaiming “There will always be a bit of Sinterklaas in Amsterdam from now on”.

“Saint Nicholas is really coming to Amsterdam now,” deacon Rob Polet told the evening news on Dutch television, “and here he will stay”.

“From the Friesch Dagblad to the Nederlands Dagblad, from Trouw to De Telegraaf: hardly any newspaper wanted to miss it,” the parish reports. “De Stentor, the Eindhovens Dagblad, the Zeeuwse PZC, and many other titles spread the news of St Nicholas. NRC Handelsblad and Het Parool even used it twice.”

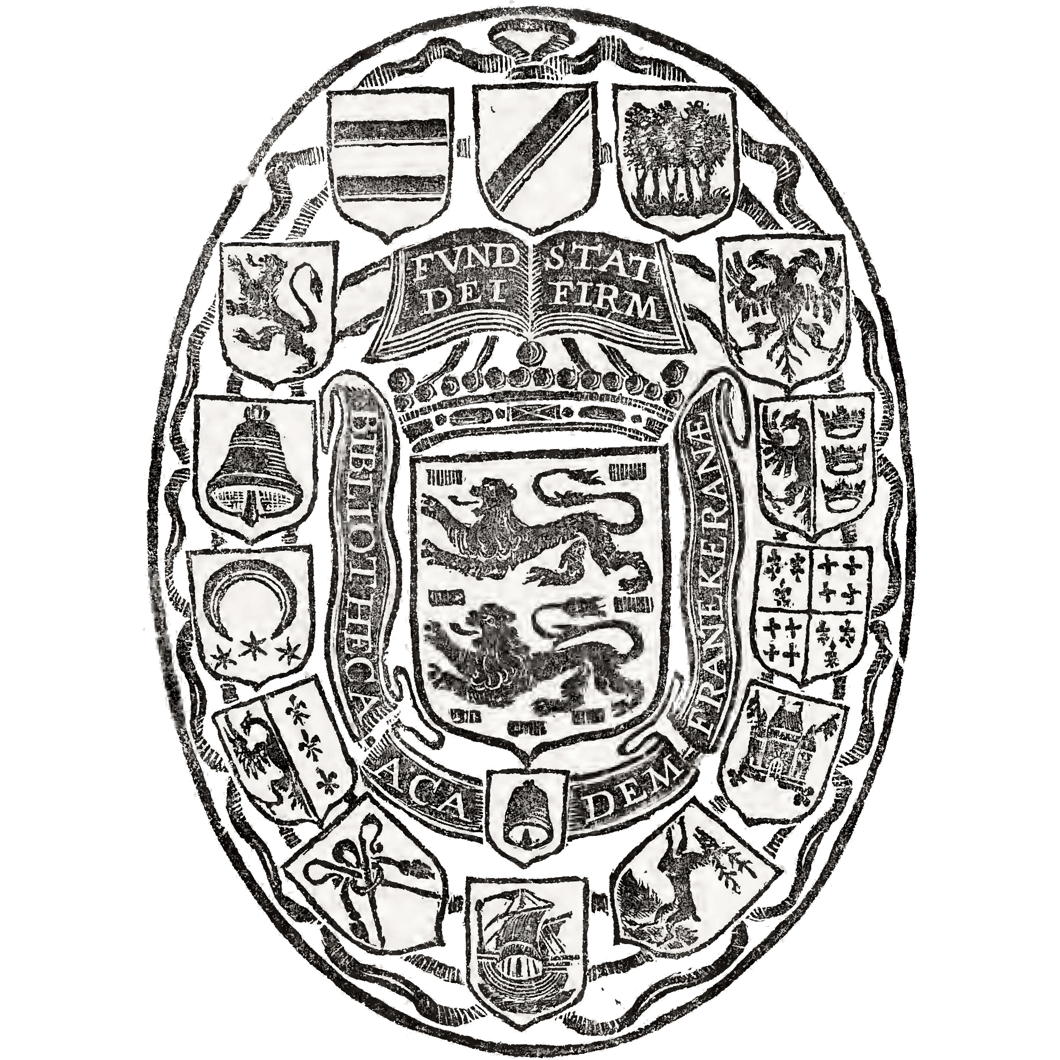

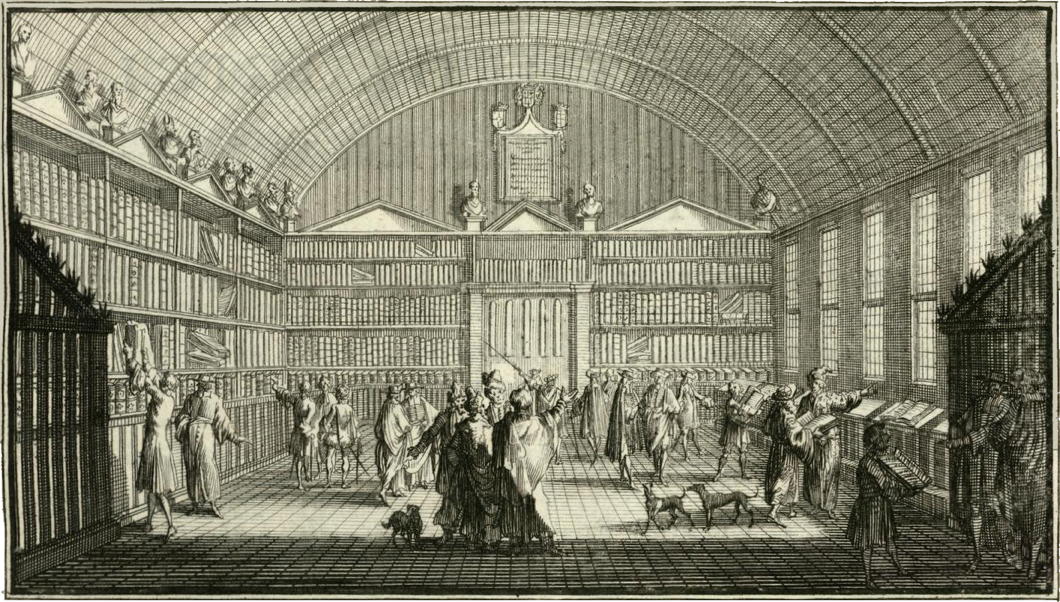

The University of the Frisians

AMONG THE CURIOUS customs of the Netherlandish universities is a unique privilege whereby Frieslanders who are postgraduate students at the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen may defend their thesis in the Church of St Martin in Franeker. This privilege is also extended to those whose dissertations are on Frisian subjects or themes. The reason for this is that Franeker — one of the historic eleven cities of Friesland and today a town of 12,000 souls — formerly had a university of its own.

The University of Franeker (or Academy of Friesland) was established in 1585 by Willem Lodewijk of Nassau-Dillenburg, stadthouder of Friesland, as a Protestant foundation in the former cloister of the Canons Regular of the Order of the Holy Cross (sometimes called the Crosiers) whose confiscated property helped fund the new university.

As the only institution of higher learning in the northern part of the United Provinces, the University of Franeker met with some success in its early decades and its Protestant theological faculty earned particular reknown.

Its most famous student — so far as I am concerned — was a young Petrus Stuyvesant who studied philosophy and languages at Franeker in the 1610s before being sent to be governor of New Amsterdam. Unfortunately the revelation of an amorous relationship with his landlord’s daughter prevented young Stuyvesant from completing his studies.

From 1614 onwards, however, Franeker found a strong competitor when a university was founded in Groningen that was more successful at drawing in students from Germanic East Frisia. By the 1790s it had only eight students.

In 1811, when the Netherlands were directly annexed to the French Empire, Napoleon abolished the university entirely, alongside those of Utrecht and Harderwijk.

Its revival under the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815 met with little success as Franeker was denied the ability to grant doctorates and in 1843 even this academy was finally suppressed.

Incidentally, the fourteenth-century Martinikerk where Frisians can defend their theses today is also the only surviving medieval church in Friesland that has an ambulatory — and restoration work in the 1940s revealed twelve pre-Reformation frescoes of saints.

a Northumbrian of Frisian and New Yorkish origin

Het Spui

Amsterdam is known for its canals, not its public squares, but Het Spui is quite welcoming all the same. The name means roughly sluice or floodgate, pointing to the unsurprisingly watery origins of the place.

At first, it was a canal like any other and was only filled in during the nineteenth century: The first part in 1867 when the neighbouring Nieuwezijds Achterburgwal was filled in, the rest in 1882, two years before the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal.

The Spui (pronounced “spouw” — unless Dawie van die bliksem corrects me) is a focal point surrounded by a number of sights. There’s the Old Lutheran Church, where the Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen met in its early years and still a working congregation today.

There’s the Maagdenhuis, built as a Catholic orphanage and also the seat of the Archpriest of Holland and Zeeland until the restoration of the hierarchy in 1856. The orphanage moved out in 1957 when the building became a bank branch but was purchased by the University of Amsterdam in 1962 to house the administration of the growing institution. (more…)

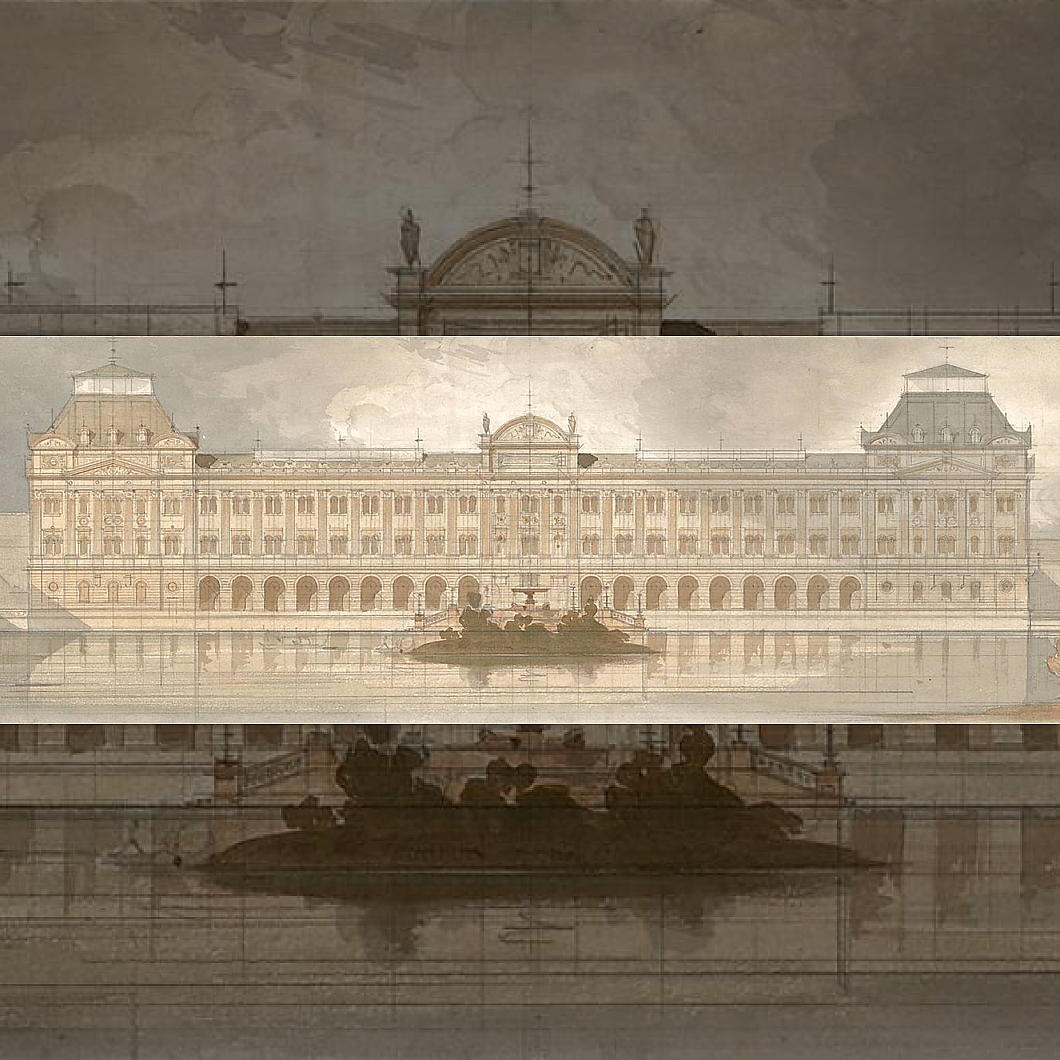

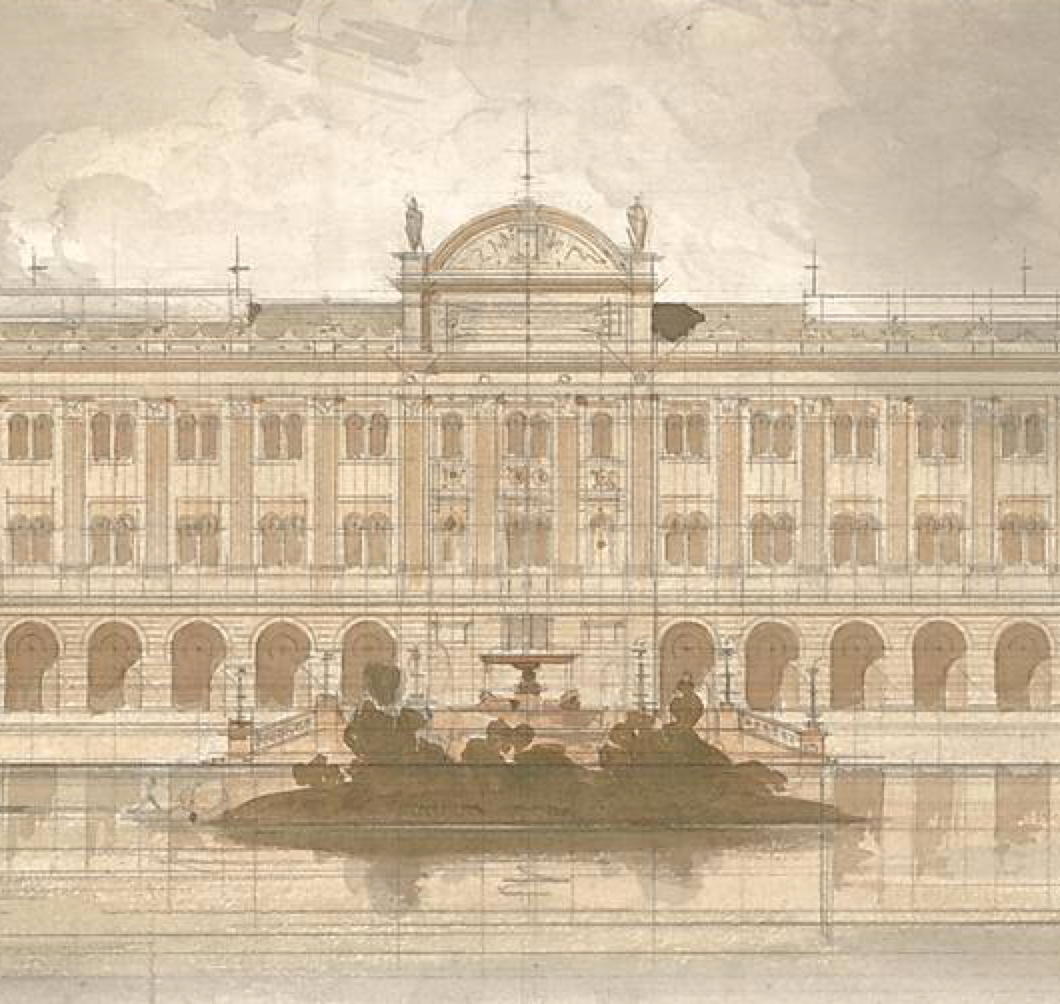

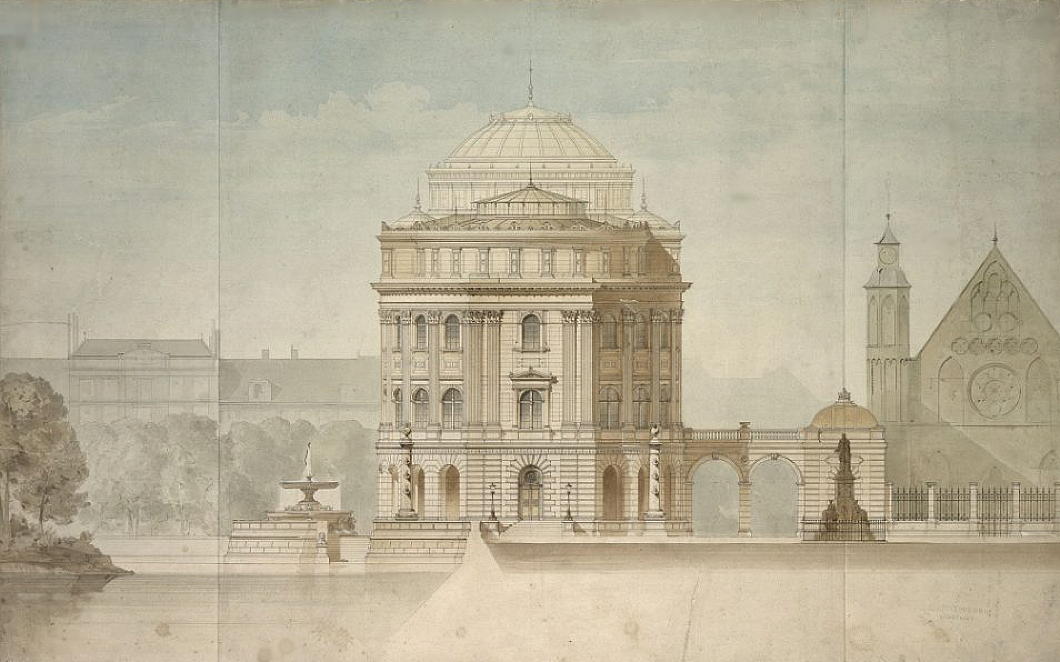

A Palace for the States-General

A Palace for the States-General

The nineteenth century was the great age for building parliaments. Westminster, Budapest, and Washington are the most memorable examples from this era, but numerous other examples great and small abound in Europe and beyond.

The States-General of the Netherlands missed out on this building trend, perhaps more surprisingly so given their cramped quarters in the Binnenhof palace of the Hague. The Senate was stuck in the plenary chamber of the States-Provincial of South Holland with whom it had to share, while the Tweede Kamer struggled with a cold, tight chamber with poor acoustics.

The liberal leader Johan Rudolph Thorbecke who pushed through the 1848 reforms to the Dutch constitution thought the newly empowered parliament deserved a building to match, and produced a design by Ludwig Lange of Bavaria. All the Binnenhof buildings on the Hofvijver side would be demolished and replaced by a great classical palace.

Despite members of parliament’s continual complaints about their working conditions, Thorbecke and Lange’s plans were vigorously and successfully opposed by conservatives. As the academic Diederik Smit has written,

A large part of the MPs was of the opinion that such an imposing and monumental palace did not fit well with the political situation in the Netherlands. […] In the case of housing the Dutch parliament, professionalism and modesty continued to be paramount, or so was the idea.

In fact, as Smit points out, significant alterations were made to the Binnenhof, like the demolition of the old Interior Ministry buildings by the Hofvijver, but these were replaced with structures that were actually quite historically convincing.

Further plans were drawn up in the 1920s — including a scheme by Berlage — but MPs felt that none of the proposals quite got things right and they were shelved accordingly. It wasn’t til the 1960s that the lack of space and the poor conditions in the lower chamber forced action. All the same, efficiency was the order of the day, as the speaker, Vondeling, made clear: “It is not the intention to create anything beautiful”.

Even then it wasn’t until the 1980s that the work was started, and the MPs moved into their new chamber in 1992. As you can see in this photograph, Vondeling’s aim of avoiding anything beautiful or showy has been achieved. The new chamber is certainly spacious — indeed some MPs claim it is too spacious. The art historian and D66 party leader Alexander Pechtold pointed out the distance between MPs inhibits real debate, unlike in the British House of Commons, and to that extent parliamentary design is inhibiting real democracy.

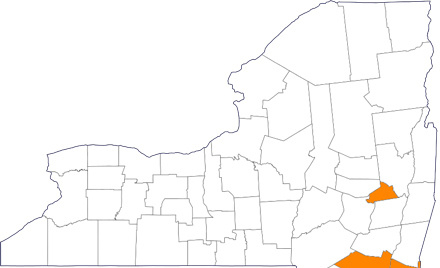

More Dutch Flags of New York

Areas shaded in orange are the counties of New York with Dutch-influenced flags

Natives and outsiders alike are often surprised when it’s pointed out just quite how much New York continues to be influenced by its Dutch foundation to this day, even though Dutch rule ended in the seventeenth century.

Previously I explored a number of local or regional flags in the state of New York that show signs of Dutch influence: those of the cities of New York and Albany, the Boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens, and the counties of Westchester, Nassau, and Orange.

I’ve since found a few more counties to add to our survey of Dutch flags in the Empire State.

Dutchess County

One of the original counties of New York established in 1683, Dutchess retains the archaic spelling of Mary of Modena’s title while she was Duchess of York. Appropriately for a county that was until very recently largely agricultural, the county seal depicts a sheaf and plough, and sits on the county’s flag with its horizontal tricolour of orange, white, and blue.

Ulster County

Across the Hudson from Dutchess County is Ulster, another of New York’s first counties. Its handsome seal features an early farmer wielding a sickle in front of a sheaf and a farmhouse, with the year of the county’s erection proudly included. The Dutch had begun to trade here as early as 1614, and the village of Wiltwijck was given municipal status by Peter Stuyvesant in 1663. Wiltwijck became Kingston in 1669 and remains a very handsome town today.

Schenectady County

The county of Schenectady is of later origin, 1809, and became industrialised in the latter half of the nineteenth century — the General Electric Company was founded here in 1892. Like Ulster and Dutchess, the county flag is just the seal displayed on an orange-white-blue tricolour.

The seal is a relatively boring depicting of crossed swords combined with the scales of justice, but on the flag it is depicted with a locomotive, canal boat, broomhead, and lightning bolt and atom.

Secret Splendor

by Andrew Cusack (Weekly Standard, 13 September 2010)

Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic

by Xander van Eck

Waanders, 368 pp., $100

This book is the first major overview and exploration of the art of the clandestine Roman Catholic churches in the Netherlands. It is not a study of paintings so much as a history in which art is like the evidence in a detective story, or perhaps even the characters in a play. It might seem extraordinary that there was a place for large-scale Catholic art during the Dutch Republic: Pre-Reformation churches had been confiscated and were being used for Calvinist services, while priests offered the Mass secretly in makeshift accommodations. Eventually a bargain between Dutch Catholics and the civil authorities emerged, trading Catholic nonprovocation in exchange for private toleration of the practice of the faith. Catholics began to purchase properties which, for all outward appearances, maintained the look of ordinary residences but whose interiors were transformed into resplendent chapels and churches.

Xander van Eck provides verbal portraits (often accompanied by contemporaneous painted ones) of several of the important clerics of the Dutch church during this period: Sasbout Vosmeer, the Delft priest influenced by St. Charles Borromeo; Philippus Rovenus, the vicar-apostolic who placed greater emphasis on clandestine parishes having specially dedicated churches, even while they kept an outward unecclesiastical appearance; and Leonardus Marius, the priest who promoted devotion to the 14th-century Eucharistic “Miracle of Amsterdam.” Marius was of such prominence that, after his death, shopkeepers rented out places on their awnings for punters to view his funeral procession. Van Eck includes a handful of amusing asides, such as the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Netherlands as a result of their constant discord with the secular clergy. Mass continued to be offered at the Jesuit church of De Krijtberg in Amsterdam “in the profoundest secrecy” — thus creating a clandestine church within a clandestine church!

The role of the clergy in sustaining the Dutch Church is unsurprising, but it is instructive to learn how instrumental laity were to keeping alive the light of Catholic faith in the Netherlands at the time. Clandestine churches relied on the generosity of Catholic families. Prominent families often provided their own kin as consecrated virgins who brought large dowries into the church, or as priests with suitable inheritances to maintain or endow clandestine parishes. The clandestine church of ’t Hart in Amsterdam, built by the merchant Jan Hartman for his son studying for the priesthood, is still open today as the Amstelkring Museum and Chapel of “Our Lord in the Attic.”

While van Eck explores the extent to which Dutch art from the period followed European norms, an emphasis on the particularity of the art of the clandestine church is to be expected. The sheer volume of art produced during this period — for just three Amsterdam churches alone there were 16 altarpieces — is partly explained by the phenomenon of “rotating altarpieces.” The paintings above the altar would be changed according to the feast or season — a practice sometimes seen in Flanders or parts of Germany but never nearly so widespread as in the Netherlands proper.

Constrained as clandestine churches were on the narrow plots typical of Dutch cities, there was no room for side chapels that might include the large funerary monuments prominent families would construct. This left altarpieces as the most convenient way for munificent Catholics to provide art for their churches: Rotating the altarpieces provided a handy way of displaying numerous commissions rather than just the donation of whoever had been generous most recently, and the themes of these commissions tended to vary in appropriateness to different feasts and seasons.

Some found fault with this method: Jean-Baptiste Descamps, visiting Antwerp in 1769, complained that the most interesting altarpieces were not permanently displayed and were more likely to be damaged in the process of being moved so often.

While the accomplishment and ingenuity of Dutch Catholics in keeping their faith during the Republic was striking, the ill-defined administrative structure of the persecuted church allowed conflicts between clerics to thrive, and doctrinal disputes emerged and festered. The disputes over Jansenism that swept over France and the Netherlands, for example, only exacerbated the administrative problems of the clandestine church. Like their Calvinist compatriots, the Jansenists tended to frown on indulgences, the veneration of saints, recital of the rosary, and private acts of worship, putting greater emphasis on the Scriptures and a more rigorous asceticism. As van Eck points out, this difference in emphasis was not exclusive to the Jansenists, but their novelty (and their heresy) was in preaching the exclusivity of their approach above all others.

Numerous vicars-apostolic had written to Rome arguing for the re-establishment of the episcopacy in the Netherlands to solve the disputes over authority, but their appeals fell on deaf ears. In 1723 a large portion of the Jansenist clergy reinstituted the episcopacy by electing an archbishop of Utrecht from their number — and were subsequently excommunicated, splitting the clandestine church and its clergy in two. (This excommunicated rump united with the opponents of papal infallibility in the following century to form a body that still calls itself the Old Catholic Church.)

When one looks at all this glorious art, not to mention the lives and pious ingenuity of the persecuted, it’s difficult not to feel a little poorer, considering the fruits of our churches in an ostensibly free era. Why does the church today commission painters who are either mediocre or trendy — or both? Artists like Hans Laagland and Leonard Porter show that good art — good liturgical art, even — is possible today, but commissions from the church for traditional artists are sadly few.

St Nicholas, Our Patron

As by now you are all well aware, today is the feast of Saint Nicholas, the patron-saint of New York. His patronship (patroonship?) over the Big Apple and the Empire State date to our Dutch forefathers of old – real founding fathers like Minuit, van Rensselaer, and Stuyvesant, not those troublesome Bostonians and Virginians who started all that revolution business.

Despite being Protestants of the most wicked and foul variety, the New Amsterdammers and Hudson Valley Dutch maintained their pious devotion to the Wonder-working Bishop of Myra and kept his feast with great solemnity.

After New Netherland came into the hands of the British (and was re-named after our last Catholic king) the holiday continued to be celebrated by the Dutch part of the population, and was greatly popularised in the early nineteenth century by the publication of a curious volume entitled A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty which purported to be by one Diedrich Knickerbocker.

In fact it was by Washington Irving, the first American writer to make a living off his pen, who did much to popularise St Nicholas Day in New York as well as to revive the celebration of Christmas across the young United States.

While, aside from hearing Mass and curling up with a clay pipe and a volume of Irving (being obsessive, I have two complete sets) here are a few links that shed some light on New York’s heavenly protector.

Historical Digression: Santa Claus was Made by Washington Irving

New-York Historical Society Quarterly: Knickerbocker Santa Claus

The History Reader: The 18th Century Politics of Santa Claus in America

The New York Times: How Christmas Became Merry

The Hyphen: Thomas Nast’s Illustrations of Santa Claus

– plus: Santa Claus and the Ladies

National Geographic: From Saint Nicholas to Santa Claus

Previously: Saint Nicholas (Index)

Hollandic Fever

Adapted from the Deborah Moggach novel of the same name, ‘Tulip Fever’ is a curious concoction. Some of the plot holes are so big you could drive a coach and horses through them. For example, how is it that – in Calvinist-controlled seventeenth-century Amsterdam – there is a massive Catholic convent perfectly accepted by everyone and operating as if nothing is out of place? It’s the size of Norwich Cathedral! (In fact, it is Norwich Cathedral – this entire production was filmed in Great Britain.)

The often excellent Chrisoph Waltz is curiously mismatched with his role here: a little bit too much of a parody of the proud, pious Amsterdam merchant in the start, which makes his eventual transformation a little unconvincing. The plot also shows little of the brilliance of its co-writer Sir Tom Stoppard. (In fact, there’s a bit too much plot.) At least Dame Judi Dench is effortless in her role as the unnamed Abbess of St Ursula. Tom Hollander is thrown in for a laugh, in a role suited to his abilities.

For curiosity’s sake the most interesting casting choice was Joanna Scanlan, known as the useless press officer at DOSAC in ‘The Thick of It’. Here she is the dressmaker Mrs Overvalt, but she was Vermeer’s cook Tanneke in ‘Girl with the Pearl Earring’. If my rudimentary calculations are correct, this means she has been in two-thirds of twenty-first-century films set in the Dutch seventeenth century.

It is, however, a beautifully shot production, for which I suspect we have the cinematographer Eigil Bryld to thank. (He’s worked on one seventeenth-century film before, and on another set in the Low Countries.) Bookended by scenes of Friedrichian romanticism (I’m into that) the film encourages me in my deeply felt belief that we need to revive seventeenth-century Dutch domestic architecture as a style.

The Dutch in Rhodesia

…and why they stayed there.

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Why did so many people emigrate from the Netherlands in the fifties? Why did hundreds of them choose to settle in what was then called Rhodesia, today’s Zimbabwe? And why did so many of them stay after 1965, when the country was led by a white-minority regime, faced an international boycott and was engulfed in a bloody guerrilla war?

De Bruyne attempted to answer these questions through a recent seminar at Leiden University’s African Studies Centre. The university has rather handily made a recording of the seminar available online.

Daar’s ook ’n interview (in Nederlands) met Mnr de Bruyne in Mare, die koerant van die Universiteit Leiden.

(Dave: hierdie post is vir jy!)

In the Old Dutch East Indies

Little Holland’s rule over this vast land – today the world’s largest Muslim country by population – never loomed large in the European imagination (the Netherlands excepted) and thus has been too easily forgotten. Peter van Dongen’s Rampokan series of graphic novels (in Herge’s ligne-claire style) is the most prominent recent attempt to shine some light on the Dutch East Indies and it has obtained a bit of a cult following.

The colonial architecture went through the usual transformations, from awkward hybrids of the motherland and the vernacular to a cool and crisp classical elegance of the later imperial buildings. Henri Maclaine Pont’s work at Bandung is probably the most successful Dutch take on local building traditions, and in some ways Geoffrey Bawa is his spiritual offspring.

The ministries of Indonesia’s government still convene in elegant Dutch colonial buildings, though the names have all changed. The Daendels Palace is now the Finance Ministry, Buitenzorg is now Bogor, and the old Koningsplein is now the Medan Merdeka or Freedom Square. (more…)

Zeist’s Zest for Traditional Architecture

The Daniel Marotplein, a residential square in the town of Zeist, provides a fine recent example of traditional architecture in the Netherlands. Designed by the TU-Delft-trained architect Diederik Six, the twenty houses surround a green square named after the Huguenot craftsman and artist Daniel Marot some of whose handiwork is in the nearby Slot Zeist.

The slot (schloss/castle/house) is associated with the Protestant Moravian brotherhood who were invited to live nearby by Cornelis Schellinger in the mid-eighteenth century, and the Daniel Marotplein takes inspiration from the two squares of houses they lived in flanking the castle. (more…)

A Baroque Church Portal

This church portal in the Oude Kerk of Amsterdam was originally in the Nieuwezijds Kapel, or Church of the Heilige Stede. That church was originally built in commemoration of the 1345 Miracle of Amsterdam, but after the ‘Alteration’ of 26 May 1578 — when Amsterdam’s Catholic city government was deposed and replaced by a Calvinist one — it and all the city’s other churches were taken over by the new Protestant administration.

In 1908 the elders of the Protestant congregation of the Nieuwezijds Kapel decided to demolish the fifteenth-century church and build a smaller one on the site, while building shops on the remainder of the site to prevent the resurgent Dutch Catholic church from building any chapel or shrine on it. This seventeenth-century baroque enclosed portal was then transferred to the Oude Kerk where it remains today.

Despite the anti-Catholicism of the Nieuwezijds Kapel elders in 1908, the Miracle of Amsterdam is still comemmorated every year on 15 March when thousands of pious Hollanders march in the evening Silent Procession (Stille Omgang). This year’s procession attracted 7,000 participants.

Smuts at Leiden

For quite some time, Leuven — in what is currently known as Belgium — was the only university in the Netherlands. It is still (barely, some argue) a Catholic university, and after the Protestant revolt sealed its rule over the northern part of the Dutch realms, William the Silent founded a university at Leiden as a Calvinist academy in 1575.

Leiden University has had strong links with South Africa from the earliest days. Ds. Johannes de Vooght — in the 1660s, the second leraar of Cape Town’s Dutch Reformed congregation — studied here, as did numerous predikante of that period and onwards, including Ds. Petrus van der Spuy, the first NGK minister to be born in South Africa.

South African politicians studied here aplenty: Sir Christoffel Brand (first Speaker of the Cape Parliament); Jan Brand (fourth president of the Orange Free State); Marthinus Steyn (sixth and final president of the O.F.S.); and Nicolaas Diederichs (third staatspresident of the Republic of South Africa).

Probably the first South African to be granted an honorary degree by Leiden (c. 1830) was Antoine Changuion, the founder of the Dutch language movement which advocated preserving Dutch as the cultural language of the Afrikaners against the emerging Afrikaans.

It was in 1948 that Leiden granted the greatest Afrikaner — Field Marshal Smuts — a Doctorate of Law honoris causa. Smuts was on his way back from Cambridge where he had been granted the honour of being installed as Chancellor of the University. Even Die Burger, a Nationalist paper opposed to his Verenigde party, found the event worthy of a caustic near-compliment:

“We may differ from him on many issues, but the honour which he has won for the Afrikaner does not leave us untouched.”

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories