Ireland

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Victory Parade, Dublin 1919

UPDATED Peter Henry’s article from Trinity News corrects my errors.

Persuant to our previous photograph of the Union Jack proudly snapping from Dublin’s General Post Office, one of our dear friends & loyal readers, a former editor of Trinity College’s newspaper, sends this photo of the 1919 Victory Parade through the streets of Dublin after the end of the Great War. The red, white, and blue here flies from the top of Trinity College, and the view looks down D’Olier Street (if I recall correctly) towards O’Connell Street in the distance. The classical portico on the left marks the entrance to the Irish House of Lords.

It is worth remembering that a great deal more Irish served in the forces of the Crown than in any republican armed forces or groups. The memory of Ireland’s great sacrifice during the First World War was shamefully neglected from the 1930s until about ten or fifteen years ago. It was a pity that the famous old Irish regiments were disbanded when independence came in 1921, rather than being continued under a native Irish command. Gone the Connaught Rangers and Dublin Fusiliers, and all the great battle honours won by Irishmen from Waterloo to far off India. (Two Irish regiments still exist in the British Army, the Royal Irish and the Irish Guards). Still, in remembrance of the dead of the First World War, one can visit the War Memorial Gardens by the banks of the Liffey, beautifully designed by Lutyens and completed after independence. The cost was split between the Irish and British governments, and, in the post-war downturn, half the workers were Irish veterans of the British Army and half were veterans of the formerly rebel forces.

Ireland remained neutral during the Second World War but declared a state of emergency, which is why the time of the war is often known in Ireland as “the Emergency”. Allied and Axis soldiers who washed up or crash-landed in Ireland found themselves interned in camps, but the Irish soldiers guarding them were only armed with blank ammunition. (Allied internees were often allowed to escape). The law of the day forbade any Irish citizen from joining a foreign military, but many soldiers of the Irish Army, policemen of an Garda Siochana, and many Irish civilians left for Britain to join the Allies in the fight, and were not punished on their return. When the port of Belfast suffered a German bombardment, fire brigades from Dundalk to Dublin were sent north irrespective of the border in order to help quell the flames.

Returning to Trinity, flying the Union Jack in 1919 would not have proved controversial in the slightest (after all, it was still the official flag of the land), but the crowds gathered again on College Green in 1945 to spontaneously celebrate the news of Germany’s surrender. The flag of Ireland with those of all the Allied nations were flown from the flagpole of Trinity, but some tactless student had placed the Union Jack at the top and the Irish Tricolour at the very bottom, below even the Soviet hammer-and-sickle. The crowd noticed this and began to howl, but some more thoughtful Trinity man swiftly took the colours down and raised them again with the Tricolour to the fore. The joyful spirit resumed.

Dublin (In the Rare Old Times)

O’Connell Street, Dublin, United Kingdom of Great Britain & Ireland.

Norn Iron Unites

What issue could be so important that it unites Northern Ireland’s four main political parties? The leaders of the Democratic Unionist Party, Sinn Féin, the Social Democratic & Labour Party, and the Ulster Unionist Party (to name the parties, from largest to smallest in number of votes) have written to Westminster MPs urging them to oppose the extension of the 1967 Abortion Act to Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland was exempt from the Act legalizing abortion in Great Britain because at the time it had its own parliament handling regional issues. The six Irish counties that have remained in the Union are the most strongly anti-abortion part of the United Kingdom.

Irish Parliament House

Please see the updated article of the Irish Houses of Parliament, College Green, Dublin here.

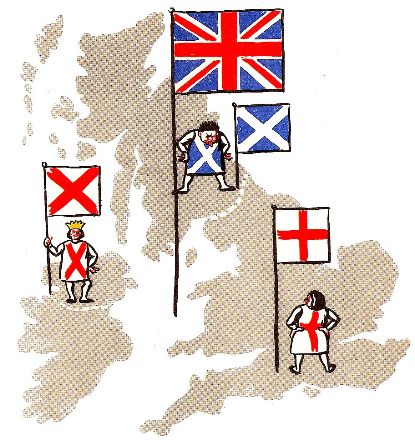

Hail Glorious Saint Patrick

THE FEAST OF IRELAND’S patron saint is an occasion for parading if ever there was one. For this, we can send part of our thanks to the British Army, which happened to initiate the most famous St. Patrick’s Day Parade of them all, namely, New York’s. It was 1762 when a number of Irish troops in the service of the Crown took it upon themselves to parade up Gotham’s own Broadway on the 17th of March. (More recently, the Duke of Edinburgh was invited to partake in the New York parade during his 1966 visit to America). Despite the lamentable outbreak of separatist republicanism in much of Ireland, the sons of Erin continue to take the Queen’s shilling and serve proudly in Her Majesty’s forces, and true to form they are sure to mark their patron’s feast day.

Lord Glenavy

Sir James Henry Mussen Campbell, Bt., 1st Baron Glenavy, PC, QC. was born in Dublin in 1851. Campbell graduated from the University of Dublin (Trinity College) a Bachelor of the Arts in 1874. He was called to the Irish bar in 1878, being made a Queen’s Counsel in 1892.

Campbell was elected to Parliament in 1898, being called to the English bar a year later. He was made Solicitor General for Ireland in 1903, as well as being appointed an Irish Privy Counsellor. He rose to become Lord Chief Justice of Ireland in 1916, being made a baronet the following year, and Lord Chancellor of Ireland the year after that (1918). Sir James was ennobled as 1st Baron Glenavy upon relinquishing office in 1921.

Ireland was partitioned in the following year, and Lord Glenavy became the first Cathaoirleach of Seanad Éireann (Presiding officer of the Irish senate). In 1923, he chaired the judicial committee investigating the establishment of a new courts system for the Irish Free State. His proposals were implemented the following year in the Courts of Justice Act 1924, forming the Irish courts as they remain today.

Having served one six-year term in the Seanad, he did not seek re-election in 1928, and died three years later in 1931. Holding the largely honorary position of President of the College Historical Society (“the Hist”), Dublin University’s debating society, from 1925, he was succeeded upon his death by his fellow Irish Protestant, Douglas Hyde, who himself later became the first President of Ireland from 1938 until 1945.

Bon Voyage

Heading to Scotland for a little bit, then down to Somerset for a spell. Dino Marcantonio, you’re in charge!

The University Church, Dublin

It is said that Newman was not a fan of the gothic revival. When he had this church built for his Catholic University of Ireland in Dublin (since then merged into the Royal University of Ireland which became the National University of Ireland, University College Dublin), he certainly made sure it was über-byzantine. Though beautiful on the inside, it has possibly the least imposing facade of any church I’ve ever seen. Perhaps that adds to its charm.

Parliament House

The Irish Parliament House, now the Bank of Ireland, on College Green in Dublin, is one of my favourite buildings in the world. You can go there and visit the House of Lords chamber. Unfortunately, the House of Commons chamber burned down shortly after the Irish Parliament was merged into the British one in 1800. It is supposedly the first purpose-built parliament building in the world, though no longer in use.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories