Great Britain

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Judging Dress

After some absence, The Sybarite has returned and, in A Love Supreme, he weighs in on the very important matter of judicial dress.

I am, it will surprise no-one to know, deeply traditionalist in such matters. I can see the argument for discarding formal court attire in cases involving children, who might be intimidated by wigs and gowns (as a child, I myself would have been as happy as a pig in the proverbial). But I feel strongly that “work clothes”, whether worn by judges, barristers, politicians or clerks in Parliament, are important. They are part of the persona. You are not Alf Bloggs, you are Mr Justice Bloggs and you are performing an important public role. When you put on the clothes, you put on the role. Of course, I am fighting a rearguard action here – I know that the tide of public opinion is against me. If the clerks at the Table in the House of Commons still wear wigs in ten years’ time, I will be (pleasantly) surprised.

As the Supreme Court was set up in the modish New Labour years, it was inevitable they would dispense with much of the ceremonial. The Justices wear lounge suits to hear cases, though I think in some cases the barristers still wear wigs and gowns. The one concession has been the black-and-gold gowns which the Justices don for special occasions. These are fine so far as they go – and, as observed above, Lady Hale of Richmond likes to accessorise hers with a Tudor bonnet – though they bear on the back the badge of the Supreme Court, which I think looks a bit tacky and smacks of footballers’ names and numbers on the back of their shirts. But they also look a bit odd worn over lounge suits or equivalent. At least successive Lord Chancellors since the role was recast by Blair have retained formal court dress for high and holy days. Mind you, the current occupant, Miss Truss, does look a bit like the principal boy in a pantomime when she wears knee breeches. But fair play to her for continuing to wear the traditional robes, even if the full-bottomed wig seems now to have gone the way of the dodo.

It could be worse. The Supreme Court Justices could wear ghastly zip-up gowns like their American counterparts – you just know they’re made of nylon – over their suits, though I have some time for Justice Ginsberg for adding a lace jabot to tidy up her garb a little. But ceremonial is something that Britain does so well. The Supreme Court could have looked so much better with Justices in gowns and traditional judicial clothing. A wig here and there wouldn’t go amiss.

I couldn’t agree more. Especially on the matter of the badge of the Supreme Court on the back on the gowns, which is simply naff. (See image below.)

But why do the justices of the Supreme Court have (what I think of as) chancellorial gowns anyhow? What is the origin of this style of black-and-gold gown? Did it start with the Lord Chancellor and spread to the Speaker or vice versa? Or have some species of judge always worn chancellorial gowns? The chancellors of universities have likewise adopted it, though its precise form varies from institution to institution, as one might expect in matters of academic dress.

Incidentally, I was speaking with Bob Geldof the other day about Senator W. B. Yeats, about whom Mr Geldof has done a documentary. As we were discussing Yeats’ contribution to the Irish Senate, Mr Geldof mentioned that Yeats had been in discussions with Hugh Kennedy, the Chief Justice of the Irish Free State, about introducing new designs for Irish judicial dress. The results, according to just about everyone, left much to be desired and so the British tradition carried on for the most part. As is so often the case, doing nothing is the least bad option.

Church of St James, Spanish Place

Always interesting to see a building you know well from a perspective you’ve never seen before, as in this photo of the Church of St James, Spanish Place, taken from Manchester Mews. The church somehow seems more imposing — like a great rounded keep.

A few months ago I was corralled into some favour or other that required a bit of muscle to move this there and whatnot, the payoff of which was it afforded an opportunity to explore the triforium of this Marylebone church and see the interior of the building from an entirely new vantage point.

It also meant being able to view in better detail the beautiful stained glass windows — many of them the gift of various Spanish royals, given that this parish originates as the chapel of the Spanish embassy (hence its name).

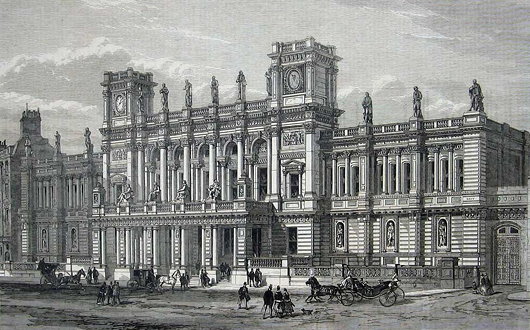

Johannes Kip’s View of London

View and Perspective of the City of London, Westminster, and St James’s Park

This view of London and Westminster is most notable for the unique perspective it takes: a bird’s eye view from above the Duke of Buckingham’s house, later acquired by the Crown and now, as Buckingham Palace, the primary royal residence.

This printing of Kip’s view, which comes up for auction soon at Daniel Crouch Rare Books, may have been printed after 1726 as it incorporates Gibb’s steeple of St Martin-in-the-Fields.

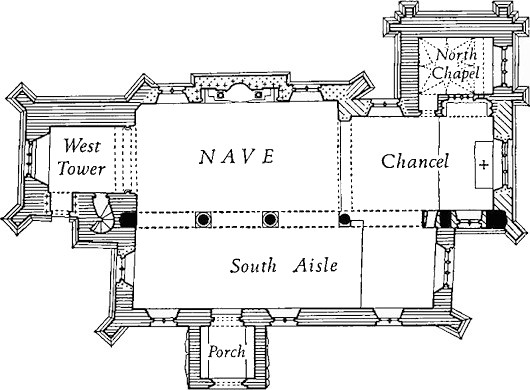

The Wyndham Monument, Silton

The charmingly haphazard Church of St Nicholas in Silton is home to what is arguably the finest funerary monument in Dorset not in a major church.

Sir Hugh Wyndham (1602–1684) lived through the difficult time of the Civil War and was first advanced in the law under Cromwell’s military dictatorship. It was the worst of both worlds for Wyndham, as the republican authorities never trusted him while after the Restoration his comfort with Cromwell meant he was deprived of office. Still, Charles II was no small-minded man, and after a royal pardon was granted Wyndham was appointed a Baron of the Exchequer and knighted.

The monument he left behind at Silton is is believed to be the earliest work of the Flemish sculptor Jan van Nost (also known as John Nost the elder). Sir Hugh is depicted in his judge’s robes, flanked by two mourning figures believed to represent his first and second wives. (The third wife is at least represented by having her arms impaled with Wyndham’s in one of the three heraldic sheilds gracing the monument’s surrounds.)

Nost’s sculpture was unveiled in the chancel of the parish church in 1692 but the Victorians thought it rather dominated the small sancutary. In 1869 a small recess was constructed in the north wall of the nave and the Wyndham monument was carefully moved there. The sculptor was also responsible for the monument to John Digby, 3rd Earl of Bristol, in Sherborne Abbey not far away, and one can see the parallels. The Earl, as it happened, married Rachel Wyndham, the younger daughter of Sir Hugh Wyndham.

A Fifty Pound Note

The recent arrival of the new fiver has caused some flurry of excitement and one of the notes finally reached the Cusackian exchequer via the barmaid at the Ox Row Inn in Salisbury on Friday night. I’m indifferent to the design; it’s inoffensive but I’d prefer to see Churchill depicted in his coronation robes rather than Yousuf Karsh’s iconic photograph.

My favourite Bank of England note, however, remains the Series D £50 first issued in 1981 designed by the Black Country artist Harry Eccleston. Sir Christopher Wren lookings crackingly baroque, and St Paul’s Cathedral looms like a great ship over the City of London he helped to rebuild after the Great Fire 350 years ago.

Eccleston was the first banknote designer to work fulltime for the Bank of England which he joined in 1958, retiring in 1983, and introduced the concept of historical figures from British history gracing the back of the notes (which are of course fronted with an image of the Sovereign). This particular note was the first fifty-pound note to be issued since 1943. It was replaced in 1994 and withdrawn from circulation two years later.

The Red Mass in Edinburgh

The opening of Scotland’s judicial year was marked this past Sunday by the Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh offering the customary Red Mass in St Mary’s Cathedral.

This year Archbishop Leo Cushley was joined by Lord Drummond Young and his fellow Senators of the College of Justice, Lord Uist, Lord Doherty, Lord Matthews, and Lady Carmichael.

Gordon Jackson QC, the Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, and Austin Lafferty of the Law Society of Scotland joined many sheriffs, QCs, advocates, solicitors, trainee solictors, paralegals, and law students.

“These men and women serve the nation in a high office and come here to ask the Lord’s blessing upon this year’s work that they carry out on our behalf,” Archbishop Cushley noted in his homily.

“Know that we appreciate the difficult and complex tasks that you have and the duties that you perform – which are very onerous – on behalf of us all and that you be assured of our prayers and our support for all that you do to apply the law of the land with virtue and with justice and with mercy.”

St Pancras Town Hall

St Pancras Town Hall is an interwar classical building by the architect A.J. Thomas (of whom I know little). The façade is a little clunky but in the warmer months it’s adorned with arrangements of flowers that soften this stern civic edifice with a bit of welcome frivolity.

When the Metropolitan Borough of St Pancras was merged with the neighbouring bailiwicks of Hampstead and Holborn to form the London Borough of Camden in 1965 this was chosen as the town hall of the new entity, so it’s now referred to as Camden Town Hall.

But of course of all the buildings under the patronage of the fourteen-year-old, fourth-century martyr Pancras, the most prominent is the international railway station across the Euston Road (below) that connects this metropolis with the rest of the continent across the Channel.

Canalside Wanderings

The sun put its hat on this weekend, and after a delicious and vaguely German breakfast by King’s Cross on Saturday I fancied a little canalside wandering. Walking the Regent’s Canal from the new Central Saint Martins all the way to Paddington, I stumbled across the Catholic Apostolic Church in Little Venice (above). It has been over ten years since I popped in to the former Edinburgh outpost of this strange and fascinating denomination, now much reduced in numbers since its apex in the late Victorian period. (more…)

Caledonian Expedition

Sun, sand, champagne, Scotland: there’s not much more you could ever want, but to have an alignment of these four in the month of October is rare. It had been quite some time since the Cusackian feet had last graced the cobbles of the beloved ‘auld grey toun’ – the Royal Burgh of St Andrews – but a friend got in touch on a Monday morning with the provocative text “Scotland Friday?” I couldn’t resist. (more…)

Papal Mace for St Andrews

Archbishop Presents New Mace to Scotland’s Oldest University Amidst 600th Anniversary

Above: The 600th Anniversary Mace.

Below: The University’s three medieval maces:

St Salvator’s College, 1461; Faculty of Canon Law, circa 1450; Faculty of Arts, 1416.

ST ANDREWS University already boasts the world’s finest collection of medieval maces, but a new ceremonial mace was added to the university’s hoard recently. In honour of the University’s six-hundredth anniversary, the Most Rev Leo Cushley, Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh, has presented the institution with a new ceremonial mace on behalf of the Catholic Church.

“This completes a triple recognition of the University St Andrews,” said Dr John Haldane, the University’s professor of philosophy.

“During his visit to Scotland at the outset of this decade, Pope Benedict referred to the university beginning to mark the 600th anniversary of its foundation, then last year Pope Francis sent a message of congratulation, and now his office has granted permission for the inclusion of his coat of arms on the head of a mace commissioned to mark the completion of several centuries and the beginning of who knows how many more.”

The silver mace with gold rose details was crafted by Hamilton & Inches of Edinburgh, who also constructed the mace of the Faculty of Medicine at St Andrews over a half-century ago. Their master silversmith Jon Hunt designed the mace, in consultation with Prof Haldane.

The mace’s head is reminiscent of Brunelleschi’s dome of Florence Cathedral, recalling St Andrews’s links with the Continent which were foremost in the University’s first century and a half while it was a Catholic institution. Atop the head a saltire design is incorporated, referencing the apostle who gave his name to both the Royal Burgh and the University as well as the country who’s first university St Andrews is.

Heraldic shields display the arms of the University and of Pope Francis who invoked “upon all the staff and students of the University, past and present, the abundant blessings of Almighty God, as a pledge of heavenly peace and joy”. (more…)

Change in the air at the Catholic Herald

Title will cease to operate as a newspaper and relaunch in magazine format

Britain’s leading Catholic publication, the Catholic Herald, will be relaunching as a magazine before the end of this year. Invites have already gone out to an event celebrating the change to be held in early December.

The relaunch might be interpreted as a move against the Tablet, which styles itself “the international Catholic weekly” and has been nicknamed “The Bitter Pill” by English Catholics for its widely perceived lack of faithfulness to Catholic teaching. The Tablet is associated with the country’s old liberal Catholic elite, counting among its trustees such figures as Chris Patten and Sir Gus O’Donnell. A Herald reader, meanwhile, is more likely to be young, intellectual, and strongly influenced by John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

When told of the news, one young churchman welcomed the change as a good move for the generally orthodox Herald against its looser rival. (more…)

The Crowned Banner

The Emblem of the Scottish Parliament

Legislatures often have their own symbols. Often these are appropriated or stylised versions of national emblems. Stormont uses a flax plant. Some time ago Westminster adopted the Tudor portcullis which now represents the Parliament of the United Kingdom — in green for the Commons or in red for the Lords.

In Scotland, however, the unicameral parliament has adopted a crowned banner as its distinctive insignia. (For previous posts on prominent emblems of modern Scottish design, see the Clootie Dumpling and the Daisy Wheel). The crown expresses authority — ultimately the sovereign power of the monarchy — while the corded banner hanging from a pommelled pole displays the Saltire, Scotland’s national flag. While early versions of the emblem were in blue, it is now standard that the symbol be depicted in purple, long a colour associated with Scotland through the national florae of heather and thistle. (more…)

In Scotland, however, the unicameral parliament has adopted a crowned banner as its distinctive insignia. (For previous posts on prominent emblems of modern Scottish design, see the Clootie Dumpling and the Daisy Wheel). The crown expresses authority — ultimately the sovereign power of the monarchy — while the corded banner hanging from a pommelled pole displays the Saltire, Scotland’s national flag. While early versions of the emblem were in blue, it is now standard that the symbol be depicted in purple, long a colour associated with Scotland through the national florae of heather and thistle. (more…)

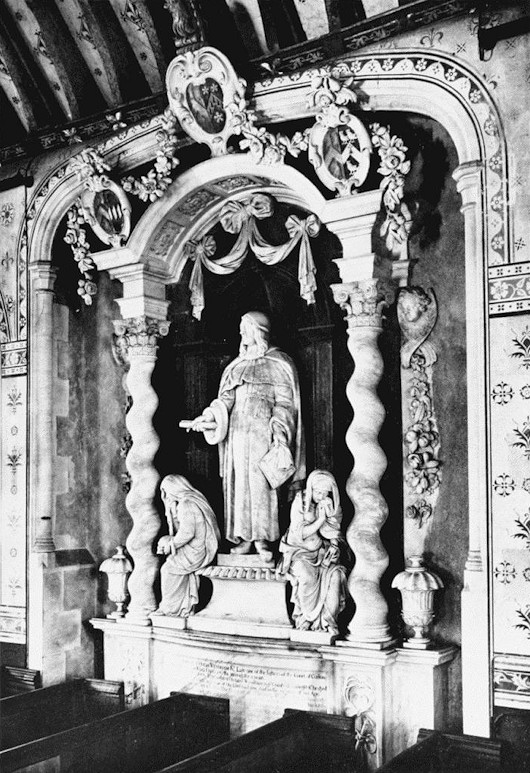

A Bunny Rampant

The carto-heraldic creativity of MacDonald Gill

If anything, I am a lover of maps, and as a cartophile it’s a fine thing that I spend half my life in South Kensington. Here you will find two of the best antiquarian map merchants around: the Map House on Beauchamp Place and Robert Frew across from the Oratory and right next door to Orsini. Milling about in front of church after mass today I received a tip-off from a friend suggesting I have a look at the window of Robert Frew, as there was a London Underground map with coats of arms of mostly abolished boroughs.

“Sounds like the sort of thing MacDonald Gill would do,” I said, and sure enough upon investigating earlier tonight it is the work of that inventive designer (and brother of Eric Gill).

The most splendid and ridiculous aspect is that in the central place among the municipal heraldry was a putative coat of arms MacDonald Gill thought up for the Underground: a rabbit rampant. Indeed, given the twin characteristics of being speedy and digging the earth, the rabbit is a perfect animal avatar for the London Underground to adopt. Don’t go looking for this design anywhere in the rolls of Garter King of Arms, though: it’s merely the invention of the creative mind of master map-maker MacDonald Gill.

Flags, Northern Ireland, and the Union

Flags have been in the news of late, perhaps as a late hangover of the disruptive protests over Belfast City Council’s decision to fly the Union Jack from Belfast City Hall only on the United Kingdom’s designated flag-flying days. Ironically, this would have brought the Six Counties further in line with normal British practice, but disgruntled unionists viewed it as a diminution of “their” flag and a bit of a fracas ensued with the once-traditional death threats and intimidation returning.

The BBC raised the issue of how Scottish independence might affect the Union Jack. (Pedants only refer to the British flag as the “Union flag”, but the Flag Institute points out both terms are perfectly acceptable). Scottish independence would have no automatic effect on the flag whatsoever, but it has provoked a round of speculation over what changes, if any, should be made to the Union flag.

Then Richard Haass, the American diplomat charged with chairing the inter-party talks on unresolved issues in the Six Counties, waded into matters vexillological when he wrote to party leaders seeking their views on the possibility of a new flag for Northern Ireland. (more…)

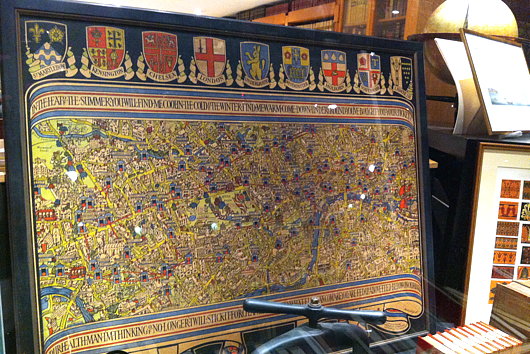

No. 6, Burlington Gardens

Sir James Pennethorne’s University of London

German university buildings are an (admittedly unusual) obsession of mine, and I’ve often thought that No. 6 Burlington Gardens is London’s closest answer to your typical nineteenth-century Teutonic academy’s Hauptgebäude. And the connection is appropriate enough, as No. 6 was built in 1867-1870 for the University of London in what had once been the back garden of Burlington House (which at the same time became home to the Royal Academy of Arts). Despite the building’s Germanic form, the architect Sir James Pennethorne decorated the structure in Italianate detail, providing the University with a lecture theatre, examination halls, and a head office. Pennethorne died just a year after drafting this design, and his fellow architects described it as his “most complete and most successful design”.

The University of London was founded as a federal entity in 1836 to grant degrees to the students of the secularist, free-thinking University College and its rival, the Anglican royalist King’s College. It now is composed of eighteen colleges, ten institutes, and a number of other ‘central bodies’, with over 135,000 students.

Since its founding, the University had been dependent upon the government’s purse for funding, as well as for housing. Accomodation was provided in Somerset House, then Marlborough House, before evacuating to temporary quarters in Burlington House and elsewhere. It was not until the 1860s that Parliament approved the appropriate grant for a purpose-built home for the University to be erected in the rear garden of Burlington House. (more…)

The Palace of Holyroodhouse

HOLYROOD IS SUCH a pleasant spot, despite the recent intrusion of an ostentatiously ugly government building designed by a Spanish architect. The other day, while visiting Edinburgh, I heeded the recommendation of the Prettiest Schoolteacher in Clackmannanshire to sample the burger at the Holyrood 9a. It was quite delicious, though not perfect, and was splendidly washed with a pint of Kozel (most un-Caledonian, I concede, but you can get Deuchars in London, you know).

Afterwards, our little party decided to have a little wander down Holyrood Road towards the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the epicentre of the Scottish monarchy.

Nestled between Calton Hill and Salisbury Crags, the Palace sits at the end of the Royal Mile that runs between it and Edinburgh Castle. With the Old Town to its west, the expanse of Holyrood Park flows off to the south and east of it. (more…)

The Lady Altar

The Oratory Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary,

Brompton Road, London

In the south transept of the Brompton Oratory is the altar dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, perhaps the finest altar in the entire church. It is a favourite place for getting in a few prayers and offering a candle or two or three or four. At the end of Solemn Vespers & Benediction on Sunday afternoon (above) it is where the Prayer for England is said and the Marian antiphon sung.

The Lady Altar was designed and built in 1693 by Francesco Corbarelli of Florence and his sons Domenico and Antonio and for nearly two centuries stood in the Chapel of the Rosary in the Church of St Dominic in Brescia. That church was demolished in 1883, and the London Congregation of the Oratory purchased the altar two years beforehand for £1,550.

The statue of Our Lady of Victories holding the Holy Child had previously stood in the old Oratory church in King William Street, and the central space of the reredos was slightly modified to house it. The Old and New Worlds are represented in the flanking statues, which are of St Pius V and St Rose of Lima — both by the Venetian late-baroque sculptor Orazio Marinali. The statues of St Dominic and St Catherine of Siena which now rest in niches facing the altar were previously united to it, and are by the Tyrolean Thomas Ruer.

London Lately

From a Pimlico rooftop, Friday afternoon.

At lunch, Friday.

A Saturday Mass in St Wilfrid’s Chapel, the Oratory.

A surprisingly sunny afternoon, yesterday in Ennismore Gardens.

A Rainy Day in Winchester

IT WAS LATE summer, neither particularly warm nor cold, and a bit rainy. I hadn’t seen Nicholas in a while but he wasn’t particularly keen on travelling into London. “Why not meet in Winchester?” he suggested, and, never having been to England’s former capital, I thought it was a good idea. I popped on the tube to Waterloo, got on a train, and in no time at all was in the county town of Hampshire. It’s a humanely size town, admirably located, and most famous for its medieval cathedral.

The thieving Protestants, not content with stealing all the cathedrals we built throughout the width and breadth of the land, highten the insult by charging admission to these former shrines and places of worship. I had arranged to meet Nicholas in the Cathedral, though, and the blighters got a good £6.50 out of me. I had a good wander round, though.

These mortuary chests contain the remains of the Saxon royalty of the kingdom of Wessex and later England.

Norman architecture is woefully underappreciated, and might form a useful style to return to today given its relative simplicity. So much Norman architecture was destroyed and replaced by Gothic during later periods of medieval prosperity, but at Winchester the Norman transepts remain.

William of Waynflete, buried here, was a high-flyer in his day. He was, varyingly, Bishop of Winchester, Headmaster of Winchester College, Provost of Eton, Lord Chancellor of England, and founded Magdalen College, Oxford. Not a bad innings.

Richard Foxe chose a more macabre memorial, but enjoyed similar success in this world: he was Bishop of Exeter, then of Bath & Wells, then of Durham, and finally of Winchester. He was Lord Privy Seal and founded Corpus Christi College at Oxford. Foxe and Erasmus sometimes wrote to eachother, and his elaborate crozier is on display at the Ashmolean.

The tomb of Henry Cardinal Beaufort is my favourite memorial in the cathedral. Beaufort — a Plantagenet — was Dean of Wells, Chancellor of the University of Oxford, Bishop of Lincoln, Lord Chancellor of England, and finally Cardinal Bishop of Winchester. He was a sometime papal legate for Germany, Hungary, and Bohemia, and most famously presided over the trial of St Joan of Arc.

One of the walls was inscribed with graffiti.

The cathedral is also the final resting place for the earthly remains of Hampshire native Jane Austen, but nevermind that.

Tours of the College were available, but we decided to leave it for another visit, and went on a wander in the direction of the Hospital of St Cross.

The Hospital of St Cross and Almshouse of Noble Poverty is the oldest charitable institution in England and the largest medieval almshouse. The church could be a small cathedral in and of itself, but as we arrived an interment was taking place, so we thought it best that it, too, was left for another day.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories